Abstract

Future increases in temperature and cloud cover will alter plant growth and decomposition of the large carbon pools stored in Arctic soils. A better understanding of interactions between above- and belowground processes and communities of plants and microorganisms is essential for predicting Arctic ecosystem responses to climate change. We measured ecosystem CO2 fluxes during the growing season for seven years in a dwarf-shrub tundra in West Greenland manipulated with warming and shading and experiencing a natural larvae outbreak. Vegetation composition, soil fungal community composition, microbial activity, and nutrient availability were analyzed after six years of treatment. Warming and shading altered the plant community, reduced plant CO2 uptake, and changed fungal community composition. Ecosystem carbon accumulation decreased during the growing season by 61% in shaded plots and 51% in warmed plots. Also, plant recovery was reduced in both manipulations following the larvae outbreak during the fifth treatment year. The reduced plant recovery in manipulated plots following the larvae outbreak suggests that climate change may increase tundra ecosystem sensitivity to disturbances. Also, plant community changes mediated via reduced light and reduced water availability due to increased temperature can strongly lower the carbon sink strength of tundra ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increasing temperatures, increasing cloud cover and changing soil water availability are part of the predictions for the future climate in the Arctic1,2. During the last decades, this region has experienced some of the highest rates of warming, which have altered plant communities3,4 and changed soil carbon (C) dynamics5,6. Since Arctic soils are estimated to contain 50% of the global soil organic C pool7,8, understanding the effect of climate changes on the mobilization of these C stocks is of great importance for predicting whether Arctic ecosystems will serve as C sinks or sources in the future.

Climate models predict continuous high warming rates in the Arctic and therefore longer growing seasons2. Based on satellite observations of tundra ecosystems, warming increases net primary production9. Furthermore, warming enhances the abundance of shrubs in the Arctic at the expense of grasses and mosses, primarily by increasing the abundance of deciduous shrubs4,10, although warming is also expanding the distribution of evergreen ericaceous shrubs11. In contrast to mosses and Arctic grasses, deciduous and ericaceous shrubs form mycorrhizal symbioses with soil fungi to facilitate their nutrient uptake12. Since warming is expected to increase plant growth and thus enhance the demand of plants for nutrients13, warming may favor an increased mycorrhizal colonization of shrub roots14,15. Warming can also affect Arctic soil microbes directly by altering the microbial community composition16,17, shifting the fungal to bacterial ratio18, and increasing microbial activity17. This may result in a faster turnover of organic matter and a higher soil nutrient availability19,20, however, possibly increasing C losses from Arctic soils, with associated feedback effects on the climate system.

Increased shrub density and height in tundra ecosystems not only reduces species richness of the plant community below the shrubs21. A denser canopy also transmits less solar radiation to the soil, thereby possibly reducing soil temperature22,23. Combined with a reduced incident radiation due to increased cloud cover2, this may further offset soil warming. A meta-analysis based on long-term ecosystem-scale experiments in the Arctic did not reveal any effects of shading on aboveground plant biomass24. However, reduced plant productivity after nine years of shading25 together with a tendency towards lower colonization of fine roots by ericoid mycorrhizal fungi26, a lower fungal abundance and an altered soil bacterial community after 15 years18, suggest a slow, yet significant, shading response in Arctic tundra ecosystems.

Mature ecosystems are considered to be less sensitive to climate change than disturbed, early-succession ecosystems27, where the vegetation are more sensitive to environmental changes28,29. Following a severe insect outbreak, the vegetation is in a state of short-term succession during which the ecosystem may be less resistant to the effects of climate change. In the Arctic, insect outbreaks can lead to defoliation even at regional scales30,31 and are known to change C cycling in subarctic forests by changing soil fungal communities32,33. The noctuid moth Eurois occulta is widely distributed across the Arctic. In Greenland, E. occulta outbreaks have been documented in peat cores as far back as the 15th century34, and several outbreaks have been recorded in Southwestern Greenland within the last century35.

Plant communities are responsible for the amount and quality of organic C entering the soil (litter and root exudates), whereas soil microorganisms control the rates of mineralization and participate in both competitive and symbiotic interactions with plants36,37,38. The strong coupling between plant and soil microbial communities makes studies that include both above and belowground processes essential for understanding ecosystem feedbacks to climate change. Future climate change could potentially decouple these interactions through differences in response rates between microorganisms and plants39, which are likely associated with differences in generation time between plants and microorganisms39,40. Still, to our knowledge no other studies in the Arctic have included detailed analyses of both above- and belowground processes, the joint responses of plant and soil microbial community compositions to climate change, and the effects of a severe natural disturbance like an insect outbreak.

The main purpose of this study was to combine analyses of above- and belowground processes and their interdependence in a tundra ecosystem where warming and shading were manipulated to mimic future climate. This was done in an Empetrum- and Salix-dominated Arctic dwarf-shrub heath in West Greenland by continuous measurements of ecosystem CO2 fluxes each year during seven growing seasons combined with analyses of the fungal community, microbial activity, soil nutrient availability, and vegetation composition after six years of treatment. We hypothesized that warming enhances the C flow through the ecosystem due to higher photosynthetic activity, altered fungal community composition and enhanced soil microbial activity, the latter of which will increase nutrient availability and the overall C sequestration at the heath site41,42. In contrast, we expected shading to decrease the C flow at the experimental site due to a reduced photosynthetic activity, a reduction in vascular plant cover, lower soil microbial activity and an altered fungal community composition. A large larvae outbreak of Eurois occulta in the fifth treatment year set back the vegetation by inhibiting the production of leaves, buds and flowers43. The experiment was accordingly also used to assess the resilience of the manipulated plots to this natural disturbance. Arctic dwarf-shrub heaths are widespread across the Arctic. We therefore expect the results from this study to significantly increase our understanding of the sensitivity of above- and belowground interactions in terrestrial Arctic ecosystems to climate change and natural disturbances, and the implications for the CO2 flux in these ecosystems.

Results

Soil moisture and temperature

Soil moisture content (% of dry weight soil) during the growing season from 2008 to 2014 fluctuated between 13% and 27% with 2008, 2009, and 2014 being the driest years (Fig. 1a). The soil moisture content was consistently lower in warming plots (p < 0.01) compared to shading and ambient plots (Fig. 1a). In addition, the days with soil moisture content below 10% of dry weight soil were markedly higher in warming plots (276 days) compared with ambient and shading plots (176 and 190 days, respectively, Supplementary Fig. S1). Neither warming nor shading affected the average soil temperature across the year or sampling period in 2013 (Supplementary Fig. S2a,b). However, for July 2013, warming increased soil temperature by 0.5 ± 0.03 °C during the day (p < 0.05), whereas shading decreased soil temperature by 0.6 ± 0.03 °C from mid-day throughout the night (p < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. S2c). This pattern showing an increase in soil temperature in the warmed plots and a decrease in temperature in shaded plots during summer was manifest in the first year of the experiment and was consistent in other years with a full set of soil temperature data throughout the year (2008 and 2011).

Average soil moisture (a), ecosystem respiration (ER) (b), net ecosystem exchange (NEE) (c), and gross primary production (GPP) (d) under mid-day conditions during the growing season from 2008–2014. An outbreak of the noctuid moth Eurois occulta affected the experimental site in 2011. Data are mean values obtained from six replicates ± s.e.m. The treatments were ambient, shading and warming. The statistical significant effects of the treatments are indicated: **p < 0.01.

Outbreak of Eurois occulta

Larvae of E. occulta were observed mainly in 2010 and 2011. During 2010, 31 larvae were caught in the pitfall traps, but in summer 2011 numbers increased dramatically peaking in July with 1842 trapped larvae. The outbreak was short-lived, as only 56 larvae were caught in August 2011 and none were caught in 2012 and 2013, The outbreak resulted in a near-complete defoliation of the plots and plant reproduction was very low, e.g. no Salix glauca catkins were observed in 2011.

CO2 fluxes and vegetation cover

An average based on the CO2-flux measurements from 2008 to 2014 showed that all plots in the dwarf-shrub heath served as a sink for atmospheric CO2 from the end of June to the end of September at the time of the measurements (midday). However, in 2011 the average net ecosystem exchange (NEE) was close to zero in both warming and shading plots and some warming plots showed overall positive NEE values indicating a CO2 source (Fig. 1c). After NEE was set back by the Eurois occulta outbreak in 2011 (Supplementary Fig. S3), NEE became more negative (i.e. increased C uptake) in following years in all plots (Fig. 1c). The climate change treatments also affected NEE. Thus, the shading (p < 0.01) and warming (p < 0.01) plots had significantly reduced net C uptake relative to ambient plots (Fig. 1c), which was concurrent with a lower gross primary production (GPP) in both treatments (p < 0.01) (Fig. 1d). Ecosystem respiration (ER) from 2008 to 2014 increased throughout the period. Shading decreased ER (p < 0.01), whereas warming increased ER (p < 0.01), except in 2014 when ambient and warming plots did not significantly differ (Fig. 1b). Taken together, the average midday CO2 accumulation was reduced by 61% in shading plots (p < 0.01) and by 51% in warming plots (p < 0.01) during the main growing season from 2008 to 2014.

After six years of manipulations, shading resulted in a significantly lower NDVI (p < 0.01; Fig. 2a). This correlated with the estimated aboveground plant biomass (p < 0.05, r2 = 0.49, Supplementary Fig. S4), which was also lower in shaded plots (p < 0.01; Table 1). The coverage of the dominant plant species E. hermaphroditum decreased by 38% (p < 0.05; Table 2). Additionally, warming plots had a reduced coverage of E. hermaphroditum by 36% (p < 0.05; Table 2). In both treatments, the cover of Salix glauca, mosses and organic crust increased, but were not significantly different from the ambient plots. As for the annual averages, NEE was significantly higher at all sampling days throughout the 2013 season in both warming (p < 0.01) and shading plots (p < 0.01), which meant a lower CO2 uptake in these plots compared to ambient plots (Fig. 2c).

Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) (a), soil respiration (b), and net ecosystem exchange (NEE) (c) measured under mid-day conditions across the growing season 2013. The “X” in plot (a) marks the soil sampling dates July 1, July 19 and September 29. Data are mean values obtained from six replicates ± s.e.m. The treatments were ambient, shading and warming. The statistical significant effects of the treatments and sampling day are indicated: **p < 0.01.

Soil pH, nutrient pools, microbial abundance, and microbial activity

After six years of manipulations, the soil pH averaged to 4.8 ± 0.4 and did not vary among treatments (Table 1). In addition there was no treatment effect on total soil C, N, and P, although total soil C:N ratio increased due to warming (p < 0.01; Table 1).

Soil nutrient concentrations were affected by sampling time with NO3 − (p < 0.01) and PO4 3− (p < 0.01) peaking in mid-season on July 19th, whereas the highest concentrations of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) (p < 0.01) and dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) (p < 0.05) were found in the end-season on September 29th (Table 3). Furthermore, shading increased the concentrations of NH4 + (p < 0.01), PO4 3− (p < 0.01), and DON (p < 0.05), while warming increased the concentrations of NO3 − (p < 0.05), PO4 3− (p < 0.05), and DON (p < 0.05) across season (Table 3).

Fungal abundance was affected by season and peaked on September 29 (p < 0.05), yet remained unaffected by the treatments. In contrast, bacterial abundance was stable throughout the season and increased in the shading plots (p < 0.05; Table 3) concomitant to a higher cellulase activity in these plots (p < 0.01; Fig. 3a). Warming enhanced microbial activity as estimated by soil respiration (p < 0.01; Fig. 2b) and induced an increased laccase activity (p < 0.05; Fig. 3b).

Soil enzyme activity of cellulase (a) and laccase (b) on July 1, July 19, and September 29 2013. Data are mean values obtained from six replicates ± s.e.m. The treatments were ambient, shading and warming. The statistical significant effects of the treatments and sampling day are indicated: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Soil fungal community responses to experimental warming and shading

In total, the fungal sequences were grouped into 1,400 OTUs. The community was dominated by Ascomycetes (91.6%), with a minor fraction constituted by Basidiomycetes (6.7%) and Zygomycetes (0.8%). The 20 most abundant OTUs represented 51.7% of the data set and mainly consisted of species from the orders Helotiales (Rhizoscyphus sp., Hyaloschyphacea sp., Hyphodiscus sp.), Pleosporales (Venturia sp.), and Hypocreales (Tolypocladium inflatum) as well as Lecaneromycetes and Archaeorhizomycetes (Fig. 4). There was no effect of sampling day on the overall structure of the soil fungal community, but six years of warming and shading altered the fungal community composition (p < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. S5). Based on the heatmap it is evident that the relative abundance of the groups Archaeorhizomycetes sp. and Archaeorhizomycetaeceae sp. I decreased due to shading (p < 0.05) and warming (p < 0.05; Fig. 4). The same was observed for Helotiaceae sp. (p < 0.01), and also the relative abundance of Rhizoscyphus ericae was decreased in shaded plots (p < 0.05; Fig. 4). In contrast, the relative abundance of Venturia sp. was higher in shading (p < 0.01) and warming (p < 0.05) plots compared to ambient plots, and likewise Hyaloscyphaceae sp. increased due to shading (p < 0.01; Fig. 4).

Heat map of the 20 most abundant OTUs in the soil fungal community on July 1, July 19, and September 29, 2013, after six years of shading and warming manipulations. The treatments were ambient, shading and warming, and statistical significant effects of the treatments on fungal OTUs are indicated: *p < 0.05. Arrows indicate the direction of the change.

To identify the drivers of the fungal community structure, a redundancy analysis (RDA) with block and sampling day as covariate was done, and this indicated a significant effect of the manipulations (p < 0.01, Fig. 5). Overall, 37.9% of the variation in the fungal community could be explained in the RDA with the first two axes explaining 10.7% and 6.7%, respectively (Fig. 5). Besides an effect of the treatment, the forward selection of explanatory variables showed that cover of ericaceous shrubs (p < 0.01), organic crust (p < 0.01), total soil N (p < 0.01), coverage of grasses (p < 0.01), total soil C (p < 0.01), and ectomycorrhizal shrub cover (p < 0.01) were the factors most strongly related to fungal community composition (Supplementary Table S3).

Partial redundancy analysis (RDA) of the soil fungal community on July 1, July 19, and September 29 2013 after six years of shading and warming manipulations in Kobbefjord, Greenland. The treatments were; A ambient, S shading, and W warming. The samples are plotted in relative size according to the number of OTUs (from 361 to 622 OTUs), and sampling date and block were covariates. Environmental variables with a significant level of p < 0.05 were included in the model (based on 1000 Monte Carlo permutations).

Discussion

Our initial hypothesis predicted a positive effect of warming on C uptake by plant photosynthetic activity44, but warming decreased GPP. During the entire experimental period, the net CO2 uptake was smaller in warming plots compared to ambient plots, which was likely caused by a reduced cover of the dominant plant species Empetrum hermaphroditum. Although temperature45 and nutrient availability46 are often considered the main limitations for plant growth in Arctic ecosystems, our data suggest that the warming treatment lowered soil water availability to a point where it limited plant photosynthetic activity. Because of a shallow soil layer at the experimental site, the plants have limited possibilities for water uptake in dry periods and thus, the reduced soil moisture caused by the warming treatment becomes an important determining factor for plant production. This is in agreement with previous suggestions that the role of soil moisture is underestimated when assessing the impact of climate change on Arctic ecosystems47.

As expected, the warming treatment increased ecosystem respiration (ER)48. Together with the reduced photosynthetic activity, this resulted in a dramatically reduced C sequestration. The higher ER was most likely an effect of a higher microbial activity, which was shown by enhanced soil respiration as well as higher enzymatic activity of laccase in the warmed soil. Soil fungi play a major role in tundra ecosystems as decomposers of organic matter49. The warming treatment changed the soil fungal community structure towards a lower relative abundance of root-associated fungi and an increase in saprotrophic fungi like Venturia sp.50,51. This change towards saprotrophic fungi may partly explain the elevated soil respiration rates despite the unaltered total abundance of fungi in the warmed soil compared to the ambient soil. Warming-induced alterations of the plant community composition were likely to be the main drivers of the observed changes to the fungal community structure. In accordance, Arctic soil fungi are mostly controlled by biological and environmental drivers such as vegetation, pH and soil moisture52,53, and soil microbial communties are known to be affected by plant community composition54. Although seasonal changes of soil microbial community compositions have been reported between summer and winter55,56, the fungal community composition was not affected by season in this experiment, which could be due to the fact that the most dramatic changes have been observed during spring thaw56, which was not part of this study.

Despite the increased C loss without a concurrent increase in C uptake, we observed no changes in the overall soil C pool. This may be due to a recent large input of organic material from the dead E. hermaphroditum plant biomass caused by the outbreak of Eurois occulta. Furthermore, this biomass may contain a high amount of protein-phenolic complexes that hinder decomposition as generally seen for ericaceous shrubs57,58, which may explain the increased laccase activity in the warming plots after six years, since laccases can decompose complex phenolic compounds59. However, warming did increase the soil C to N ratio after six years of warming suggesting an increased N mineralization10, which was supported by the higher concentrations of both DON and NO3 − in the soil. The elevated concentrations of DON and NO3 − along with elevated concentration of PO4 3− indicate that plant activity in the warmed plots was not limited by the concentration of plant available N and P.

Although shading effects on plant biomass in Arctic tundra ecosystems are previously reported to be limited24, we found a decrease in aboveground plant biomass and NDVI after six years of shading treatment. The shading induced decrease of Empetrum hermaphroditum abundance likely explains the lowered GPP. In addition, the combination of reduced ER and unaltered soil respiration in the shaded plots indicates that shading reduced aboveground plant activity and hence affected directly the C uptake capacity of the plant community.

The unaltered soil respiration rates as well as enhanced cellulase activity, higher abundance of bacteria and increase in relative abundance of Venturia sp. after six years of treatment contrast our initial hypothesis that shading lowers microbial activity due to lower soil temperature and reduced organic C input from litter and root exudates. The result is, however, in accordance with results from a Swedish subarctic heath18 and indicates that the main effect of the shading treatment at our experimental site is a lowered C uptake induced by the reduced incoming solar radiation and to a lesser extent by the lowered soil temperature.

Although the warming and shading treatments created different environmental conditions, both treatments changed the fungal community structure in a similar direction. In both climate manipulations, the relative abundance of the saprotrophic Venturia sp. increased, while the root-associated Archaeorhizomycetes groups60 decreased. However, the decrease in the relative abundance of root-associated fungi was more pronounced in shaded soils where e.g. the ericoid mycorrhizal species Rhizoscyphus ericae 61 decreased. Although root colonization of ericoid mycorrhizal fungi can decrease due to shading26, the response in the shaded plots is likely linked to the reduced cover of ericaceous shrubs. However, we are not able to establish if a decrease in E. hermaphroditum led to a decrease in R. ericae, or vice versa. The decrease in the relative abundance of mycorrhizal partners in the shaded plots may be expected to impact plant performance. On the other hand, the increased concentrations of plant available N and P in these plots may alleviate the need for a mycorrhizal partner.

The larvae outbreak by Eurois occulta in the fifth treatment season, 2011, lowered GPP and NEE in all plots. The combination of larvae outbreak and climate treatments significantly decreased the cover of E. hermaphroditum, while a non-significant expansion of Salix glauca, mosses and organic crust was observed. The increase in S. glauca cover was mainly caused by an increase in the size of individual plants and less by establishment of new plants.

Despite low numbers of moths in 2012, flower production was very low in 2012 indicating that the plants responded to the outbreak by allocating resources to growth and not to reproduction. The increased ER in the years following the outbreak (2012–2014) likely reflects an increased allocation of plant resources into growth including increased below-ground biomass. In fact, GPP was about twice as high in 2012–2014 compared to 2008–2010, which may have been facilitated by nutrients released from larval feces and carcasses62. A strong plant recovery following a larval outbreak was also observed in Kangerlussuaq, West Greenland63, indicating that tundra ecosystems are well adapted and resilient to insect outbreaks. However, the response of GPP was stronger under ambient conditions (i.e. greater difference between post- and pre-outbreak GPP) compared to the two treatments. This indicates a fast recovery of plant C uptake in ambient plots and a lowered resilience under future climate, possibly because water limitation in warming plots and light limitation in shading plots prevented a full recovery of the already stressed plant communities. In accordance, disturbed, early-succession ecosystems are considered to be more sensitive to climate change compared to mature ecosystems27.

Little is known about the biotic and abiotic parameters triggering an E. occulta outbreak. However, warmer climate is expected to increase the prevalence and intensity of insect outbreaks in high latitude ecosystems64,65. Thus, a northward expansion of moth outbreaks in northern Scandinavia is likely related to warmer winters as eggs experience enhanced winter survival30. Indeed, the two winters preceding the outbreak (2009/2010 and 2010/2011) were 4.0 and 2.2 °C warmer than the mean for 2008–2014.

Whether net ecosystem C storage increases or decreases in Arctic ecosystems depends on the balance between C uptake by plants and C loss from the soil organic matter pool. The predicted shrub expansion in tundra ecosystems due to warming4 might result in more C being bound in the aboveground woody plant biomass66. However, while warming slightly increased coverage of Salix glauca (p = 0.0984) in this study, in line with previous studies from the Arctic4,10, the dominant shrub Empetrum hermaphroditum decreased at a greater extent. The high concentration of protein-phenol complexes in E. hermaphroditum necromass may inhibit the invasion of e.g. Salix seedlings57. Thus, natural disturbances like moth outbreaks in combination with difficulties for seedling establishment following E. hermaphroditum die-back may slow down the greening of the Arctic.

The marked decrease of E. hermaphroditum after six years of warming and shading strongly affected NEE and consistently lowered C uptake in the dwarf-shrub heath. Although the fungal community composition was strongly affected by the plant community, the overall microbial activity did not follow the aboveground responses, thereby contributing to the dramatically reduced C accumulation in the dwarf-shrub heath during the growing season under a simulated future climate with elevated temperature or cloud cover. Furthermore, the reduced recovery of GPP after the larvae outbreak in the climate manipulation plots indicated enhanced ecosystem sensitivity to disturbances of Arctic ecosystems subjected to climate change. This may enhance the decoupling between above and belowground processes and further increase the sensitivity of the Arctic dwarf-shrub heath to C loss in a future changing climate where the frequency of insect outbreaks may increase.

Methods

Study area

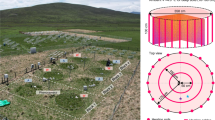

The study site is an Arctic dwarf-shrub heath (vegetation height approx. 20–30 cm) dominated by the ericaceous shrub Empetrum hermaphroditum L. and the deciduous shrub Salix glauca L. with a scattered distribution of mosses, lichens, bare soil and bed rock (Table 3). The soil layer is shallow with a varying depth of 3–8 cm. The site is located in Kobbefjord approximately 20 km East of Nuuk, Greenland (64°07′N, 51°21′W), where the annual precipitation is 752 mm and the mean temperature is −1.4 °C43,67. In most years, the growing season is from late May to late September with snow melt occurring at day of year 148 as average for the study period. July is the warmest month with an average day temperature of 10.6 °C43. The annual average precipitation at the site from 2007–2014 was 859 mm (Supplementary Table S1). In the soil sampling year, 2013, snow melted in late May and the growing season began shortly thereafter and ended in late September.

Experimental setup

The experiment was setup in 2007 as a part of the long-term Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring (GEM) program68 with an untreated plot (ambient, A), an open-top International Tundra Experiment (ITEX) chamber plot that increases the soil temperature by 1-2 °C (warming, W)4,69,70, and a shading plot (shading, S) where hessian tents remove 60% of the incoming light68,71,72. All plot types (1.5 × 1.5 m) are replicated in six blocks. The hessian tents over the shaded plots not only exclude incoming light but also decreased soil temperature from noon until late night (Supplementary Fig. S2c). Each year, open-top chambers and hessian tents were installed at the beginning of the growing season and taken down before first snowfall in autumn.

Quantification of the noctuid moth Eurois occulta

The relative number of E. occulta larvae and other arthropods were obtained during the plant growing season by weekly sampling of eight pitfall traps at four locations within a few hundred meters of the experimental site. The traps contained ca. 200 mL H2O with one teaspoon of NaCl and two drops of Änglemark dishwashing detergent (Coop, Albertslund, Denmark).

CO2 flux measurements

Ecosystem CO2 fluxes were measured weekly during the main growing season from 2008 to 2014. For exact sampling periods, see Supplementary Table S2. In 2013, the measurements took place from June 25 to September 28 by placing a plexiglas chamber (height: 0.34 m) onto a fixed metal frame (0.33 × 0.33 m) in each plot. The chamber was equipped with a HTR-2 probe logging photosynthetic active radiation and temperature during the gas flux measurements and a fan for air circulation. The probe was connected to an EGM4 (Environmental Gas Monitor, PP Systems, Amesbury, Massachusetts, USA) and a computer logging the development in CO2 concentration in the chamber every 10 sec (13 data-points per plot). Net ecosystem exchange (NEE) was determined under ambient light conditions. Then the flux chamber was aerated and covered with black plastic in order to determine ecosystem respiration (ER). Gross primary production (GPP) was estimated as the sum of NEE and ER.

In 2013, soil respiration was measured by means of PVC tubes (12 cm diameter; 6 cm high) placed 2-3 cm into the soil where there was no vegetation cover. The tubes were installed a week before the first measurements and soil respiration was measured as CO2 accumulation for 1 min using a LI-6400XT portable system together with a 6400-09 soil CO2 flux chamber (LICOR, Biosciences, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA). The soil respiration was hereafter measured concurrent with the chamber measurements.

Vegetation analyses

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) was measured in each plot concurrent with the CO2 flux measurements using a SpectroSense 2 (Skye Instruments, Llandrindod Wells, UK). In addition, the plant community composition was estimated in mid-July 2013 by pinpoint analysis in each plot using a 1 m × 1 m frame with 101 fixed points, where the number of hits on a new plant species was noted, as was hits on moss, lichen, dead crust and bare rock. The abundance of all plant species, mosses, lichens, organic crust, and bare rock was noted. Furthermore, total aboveground plant biomass was estimated for each plot based on linear regressions for each plant species between the results of a 0.35 m × 0.35 m pin-point analysis with 25 fixed points and the dry harvest weights. The latter was determined from additional plots at the experimental site, in which plant biomass was harvested and the dry weights determined.

Soil sampling and characterization

To estimate the impact of the experimental setup, soil moisture at 2-3 cm depth was measured using a ThetaProbe Soil Moisture Sensor (Delta-T Devices, Cambridge, UK) throughout the season, and the soil temperature logged every hour 3–5 cm below the surface of each plot (n = 6) using GeoPrecision M-Log 5 W wireless temperature loggers (CiK solutions, Karlsruhe, Germany).

Soil samples (2 cm in diameter) were collected from all plots on July 1st, July 19th and September 29th 2013 by pooling three soil cores of the entire humus horizon from each plot. The soil samples were homogenized gently by hand in a metal frame, which was carefully cleaned in-between samples and 20-g soil samples were kept in sterile plastic bags at −20 °C until DNA extraction and enzyme assays were performed at laboratories in Copenhagen. Water content was determined by drying 5 g of fresh soil at 70 °C for 48 hours, whereafter soil organic matter (SOM) was determined as ignition loss when burning the dried soil at 550 °C for 6 hours. The pH was measured in a suspended solution of 5 g fresh soil in 20 mL double-distilled water (ddH2O).

For analysis of water extractable nutrients, 5 g fresh soil was extracted in 25 mL ddH2O for 1 hour to recover inorganic nitrogen (NH4 +-N and NO3 −-N), inorganic phosphorus (PO4 3−P), dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and dissolved organic N (DON)73. All extracts were filtered through Whatman GF-D filters and frozen at −18 °C until further chemical analyses.

DOC was analyzed with a Shimadzu TOC-L CSH/CSN total organic C analyzer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Inorganic N was analyzed as follows: NH4 +-N using the indophenol blue method and NO3 −-N colorimetrically using the cadmium reduction method, both with a FIAstar 5000 flow injection analyser (FOSS Tecator, Höganäs, Sweden). DON was analyzed with FIAstar 5000 after digesting the extracts in H2SO4 with Se as a catalyst. PO4 3− was analysed photospectrometrically by the molybdenum blue method74.

In addition, total soil C, N, and P were analyzed in subsamples of freeze-dried soil using a LECO TrueSpecTM CN analyzer (LECO, St. Joesph, Michigan, USA).

Enzyme assays

Extracts for enzyme assays were prepared by shaking (150 rpm) 5 g of soil with 45 mL of sterile 0.9% NaCl for 1 h, where after 10 mL of the soil slurry was transferred to 15-mL tubes and horizontally shaken (300 rpm) with glass beads (2 mm) for 15 min. The extracts were used for assays directly. For all assays three negative controls were prepared using 5 g of autoclaved soil (randomly picked from the samples). All incubations were made in duplicates on a Gen5 2.0 Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, Vermont, USA).

For the cellulase assay 200 µL soil slurry were transferred to a 96-well microtitter-plate and mixed with 200 µL substrate solution of carboxymethyl cellulose dyed with remazol brilliant blue (4 M, pH 5.0) and incubated with shaking (350 rpm) for 24 h at 40 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding 1 mL of precipitation solution (20% sodium acetate trihydrate and 3% zinc acetate in 100 mL milliQ water; pH adjusted to 5.0 by HCL), incubated for 10 min at room temperature, centrifuged, the supernatant (200 µL) transferred to a new microtitter-plate, and the absorbance measured at 590 nm75.

For laccase, 20 µL of soil slurry were transferred to a 96-well microtitter-plate and mixed with 50 µL of ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) (50 mM) and 130 µL sodium-acetate buffer (100 mM, pH 5.0). The plate was incubated with shaking (100 rpm) for 1 h at room temperature and then centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 4 min. The supernatant (200 µL) was transferred to a new plate and absorbance measured at 420 nm75.

DNA extraction and quantitative PCR

DNA was extracted from 0.25 g freeze-dried soil using FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil, according to manufacturer’s standard protocol (MP Biomedicals, Solon, Ohio, USA). The DNA was kept at −18 °C and used for both quantitative PCR (qPCR) and PCR amplicon sequencing.

Fungal and bacterial abundance in the soil was estimated by qPCR using 20 µL reactions on Mx3000 P (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA) targeting the ITS2 region for fungi using ITS476 and ITS777 primers, and targeting bacterial 16S rDNA by EUB338F and EUB518R primers78. The qPCR reactions were run in technical duplicates and contained 10 µL of SYBR® Green QPCR Master Mix, 2 µL of each primer (770 nM final concentration), 1 µL of DNA template, and 5 µL of ultraclean water (Sigma-Aldridge, St. Louis, Missouri, USA). The qPCR program for 16S rDNA amplification was: 95 °C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 20 s, and a final dissociation curve. The standard curve for bacteria was made from E. coli sø3339. The qPCR program used for amplification of the ITS region was: 94 °C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, and a final dissociation curve. The standard curve for fungi was made from Aureobasidium pullulans. After the sequencing results of the ITS region were obtained, the qPCR results were adjusted for amplified plant DNA.

Sequencing of soil fungal community

The primers ITS4 and ITS7 were used to amplify the ITS2 region for sequencing. PCR amplifications were done in two steps. The first step using illustra puReTaq Ready-To-Go PCR Beads (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) only added primers and template DNA (1 µL). The PCR-I conditions were 94 °C for 2 min; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, followed by 72 °C for 5 min. The second step was done using 2 µL of the 10x diluted PCR-I product in a reaction mixture including 0.15 µL DNA polymerase (AccuPrime™ Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltman, Massachusetts, USA), 2 µL 10x AccuPrime™ PCR Buffer II, 1 µL (770 nM) of the each primer (custom tagged forward and reverse primer), and 13.85 µL ddH2O to a 20 µL reaction volume. The conditions for PCR-II were 94 °C for 2 min; 14 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, followed by 72 °C for 5 min. Amplicons were then purified from a 1% agarose gel using Montage Gel Extraction Kit (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA). Amplicon concentrations were quantified for all samples using Qubit dsDNA HS Assay and measuring the fluorescence on Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen). Samples were pooled in equimolar amounts and paired-end sequenced on a MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, California, USA).

Processing sequence data

Sequences were processed using Qiime 1.779. Sequences were trimmed of primer sequences and barcodes and assembled using a custom script. Sequences that could not be assembled were removed as well as chimeras and sequences with a quality score less than 20. The remaining sequences (6.5 × 106 reads with an average read length of 435 bp) were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs), using Usearch 5.2.23680 at 97% similarity level in Qiime. OTU-clusters containing less than 100 reads were removed. The remaining OTUs were classified using RDP classifier81 against the UNITE database82.

The result of this classification contained two major groups ‘Fungi sp.’ and ‘Fungi, Ascomycota sp.’ containing 575 OTUs with > 100 reads and accounting for 23.5% of the data. These were BLASTed through the NCBI NT database, in an attempt to obtain a higher taxonomic resolution. Alignment parameters were modified from default: Word size = 11, reward = 2, gapopen = 4, gapexted = 2. Hits with e-value < 10−5 were discarded. Taxonomy was voted upon with the BROCC83 1.1.0 pipeline with the default ‘amplicon’-mode parameters. This resulted in re-classification of 113 OTUs, accounting for 11% of the dataset. Another 113 OTUs (0.25%) were classified outside the fungal kingdom and were removed from the dataset. 349 OTUs (12%) did not obtain better classification. All annotations in the classification of ‘other’, ‘unknown’, ‘unidentified’, ‘uncultured’ and ‘Incertae sedis‘ were designated as ‘unknowns’ even though a categorical difference in these terms do exist.

After all removals, the dataset consisted of 4.1 × 106 reads, 1,400 OTUs and 151 taxonomic groups. Sample 4 W and 6 C from July 1st contained low amounts of assembled reads and were removed from the dataset. The remaining samples were rarefied to 8,680 reads per sample before the between-sample community analysis. The sequences are available from GenBank with accession numbers KR265904 - KR267303.

Statistical analyses

Analyses of variance (ANOVA) were done using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). The effects of nutrient concentrations, enzyme activity, plant biomass, vegetation abundance, and fungal and bacterial abundance were analyzed by linear mixed model with block as random factor. A similar model was used for analyzing the effects of sampling day. Time series of soil moisture, ecosystem respiration, soil respiration, soil temperature, net ecosystem exchange and NDVI were analyzed by repeated measurement ANOVA with block as random factor. Dunnett’s test was used to identify the difference between ambient (control conditions) and either shading or warming treatments. All significant (p < 0.05) results are reported in figures and tables.

A between-groups analyses of the fungal community composition in the different treatments was performed in R83 using the package ‘ade4’84,85 based on a Euclidean distance matrix of the rarefied OTU table, with 106 Monte-Carlo permutations. In addition, a heatmap of the 20 most abundant OTUs was produced in R using the packages ‘vegan’86 and ‘rioja’87. Furthermore, the treatment effects on theses 20 clusters were analyzed by STAMP v. 2.0.988.

A redundancy analysis (RDA) was done in CANOCO 5 (Microcomputer Power, Ithaca, New York, USA) with sampling day and blocks as covariates, and explanatory factors were accepted by forward selection with a significant level of p < 0.05 based on 1000 Monte Carlo permutations followed by Bonferroni correction of the p-values. All analyzed environmental factors were included in the forward selection except for CO2 flux measurements, fungal abundance and enzyme activity. Response variables (rarefied OTU abundance) were arcsine-transformed and centered as recommended by Ramette89. Explanatory variables (environmental data) were centered and standardized by z-score calculations as default in CANOCO 590.

The ITS2 sequences generated during the current study are available in GenBank with accession numbers KR265904 - KR267303, while other data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

ACIA Impacts of a Warming Arctic: Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

IPCC Stocker, T. F. et al. eds Summary for policymakers in Climate Change2013: the Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Tape, K., Sturm, M. & Racine, C. The evidence for shrub expansion in northern Alaska and the Pan-Arctic. Global Change Biology 12, 686–702 (2006).

Elmendorf, S. C. et al. Global assessment of experimental climate warming on tundra vegetation: Heterogeneity over space and time. Ecology Letters 15, 164–175 (2012).

Schuur, E. A. G. et al. The effect of permafrost thaw on old carbon release and net carbon exchange from tundra. Nature 459, 556–559 (2009).

Elberling, B. et al. Long-term CO2 production following permafrost thaw. Nature Climate Change 3, 890–894 (2013).

Mcguire, A. D. et al. Sensitivity of the carbon cycle in the Arctic to climate change. Ecological Monographs 79, 523–555 (2009).

Tarnocai, C. et al. Soil organic carbon pools in the northern circumpolar permafrost region. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 23, GB2023 (2009).

Sitch, S. et al. Assessing the carbon balance of circumpolar Arctic tundra using remote sensing and process modeling. Ecological Applications 17, 213–234 (2007).

Aerts, R., Cornelissen, J. H. C. & Dorrepaal, E. Plant performance in a warmer world: General responses of plants from cold, northern biomes and the importance of winter and spring events. Plant Ecology 182, 65–77 (2006).

Sorensen, P., Lett, S. & Michelsen, A. Moss-specific changes in nitrogen fixation following two decades of warming, shading, and fertilizer addition. Plant Ecology 213, 695–706 (2012).

Hobbie, J. E. & Hobbie, E. A. N-15 in symbiotic fungi and plants estimates nitrogen and carbon flux rates in Arctic tundra. Ecology 87, 816–822 (2006).

Rustad, L. E. et al. A meta-analysis of the response of soil respiration, net nitrogen mineralization, and aboveground plant growth to experimental ecosystem warming. Oecologia 126, 543–562 (2001).

Clemmensen, K. E., Michelsen, A., Jonasson, S. & Shaver, G. R. Increased ectomycorrhizal fungal abundance after long-term fertilization and warming of two arctic tundra ecosystems. New Phytologist 171, 391–404 (2006).

Deslippe, J. R. & Simard, S. W. Below-ground carbon transfer among betula nana may increase with warming in Arctic tundra. New Phytologist 192, 689–698 (2011).

Deslippe, J. R., Hartmann, M., Simard, S. W. & Mohn, W. W. Long-term warming alters the composition of Arctic soil microbial communities. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 82, 303–315 (2012).

Timling, I. & Taylor, D. L. Peeking through a frosty window: Molecular insights into the ecology of Arctic soil fungi. Fungal Ecology 5, 419–429 (2012).

Rinnan, R., Michelsen, A., Baath, E. & Jonasson, S. Fifteen years of climate change manipulations alter soil microbial communities in a subarctic heath ecosystem. Global Change Biology 13, 28–39 (2007).

Nadelhoffer, K. J., Giblin, A. E., Shaver, G. & Linkins, A. E. Microbial processes and plant nutrient availability in arctic soils in Arctic Ecosystems in a Changing Climate: An Ecophysiological Perspective (eds Chapin, F. S. I., Jefferies, R., Reynolds, J. F., Shaver, G. & Svoboda, J.) 281–300 (Academic Press, 1992).

Aerts, R. The freezer defrosting: Global warming and litter decomposition rates in cold biomes. Journal of Ecology 94, 713–724 (2006).

Pajunen, A. M., Oksanen, J. & Virtanen, R. Impact of shrub canopies on understorey vegetation in western eurasian tundra. Journal of Vegetation Science 22, 837–846 (2016).

Bonfils, C. J. W. et al. On the influence of shrub height and expansion on northern high latitude climate. Environmental Research Letters 7, 015503 (2012).

Juszak, I., Erb, A. M., Maximov, T. C. & Schaepman-Strub, G. Arctic shrub effects on NDVI, summer albedo and soil shading. Remote Sensing of Environment 153, 79–89 (2014).

Van Wijk, M. T. et al. Long-term ecosystem level experiments at toolik lake, alaska, and at abisko, northern sweden: Generalizations and differences in ecosystem and plant type responses to global change. Global Change Biology 10, 105–123 (2004).

Chapin, F. S. & Shaver, G. R. Physiological and growth responses of arctic plants to a field experiment simulating climatic change. Ecology 77, 822–840 (1996).

Olsrud, M. & Michelsen, A. Effects of shading on photosynthesis, plant organic nitrogen uptake, and root fungal colonization in a subarctic mire ecosystem. Botany-Botanique 87, 463–474 (2009).

Kröel-Dulay, G. et al. Increased sensitivity to climate change in disturbed ecosystems. Nature Communications 6, 6682 (2015).

Anderson-Teixeira, K. J. et al. Altered dynamics of forest recovery under a changing climate. Global Change Biology 19, 2001–2021 (2013).

Luo, Y. & Chen, H. Y. H. Observations from old forests underestimate climate change effects on tree mortality. Nature Communications 4, 1655 (2013).

Callaghan, T. V. et al. Effects on the structure of Arctic ecosystems in the short- and long-term perspectives. Ambio 33, 436–447 (2004).

Post, E. et al. Ecological dynamics across the Arctic associated with recent climate change. Science 325, 1355–1358 (2009).

Saravesi, K. et al. Moth outbreaks alter root-associated fungal communities in subarctic mountain birch forests. Plant Microbe Interactions 69, 788–797 (2015).

Parker, C. T. et al. Slowed biogeochemical cycling in sub-Arctic birch forest linked to reduced mycorrhizal growth and community change after a defoliation event. Ecosystems 20, 316–330 (2016).

Iversen, J. Moorgeologische untersuchungen auf Grönland. Meddelelser fra Dansk Geologisk Forening 362, 341–358 (1934).

Lund et al. Larval outbreaks in West Greenland: instant and subsequent effects on tundra ecosystem productivity and CO2 exchange. Ambio 46(Suppl. 1), 26–38 (2017).

Broeckling, C. D., Broz, A. K., Bergelson, J., Manter, D. K. & Vivanco, J. M. Root exudates regulate soil fungal community composition and diversty. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 74, 738–744 (2008).

Van der Heijden, M. G. A., Bardgett, R. D. & Van Straalen, N. M. The unseen majority: Soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecology Letters 11, 296–310 (2008).

Deslippe, J. R., Hartmann, M., Mohn, W. W. & Simard, S. W. Long-term experimental manipulation of climate alters the ectomycorrhizal community of betula nana in Arctic tundra. Global Change Biology 17, 1625–1636 (2011).

Bardgett, R. D., Manning, P., Morrien, E. & De Vries, F. T. Hierarchical responses of plant-soil interactions to climate change: Consequences for the global carbon cycle. Journal of Ecology 101, 334–343 (2013).

Yergeau, E. et al. Shifts in soil microorganisms in response to warming are consistent across a range of Antarctic environments. ISME Journal 6, 692–702 (2012).

Schimel, D. S. et al. Climatic, edaphic, and biotic controls over storage and turnover of carbon in soils. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 8, 279–293 (1994).

Schlesinger, W. H. & Andrews, J. A. Soil respiration and the global carbon cycle. Biogeochemistry 48, 7–20 (2000).

Jensen, L. M. ed. Nuuk Ecological Research Operations, 5th Annual Report, 2011 (Aarhus University, DCE – Danish Centre for Environment and Energy, 2012).

Illeris, L., Christensen, T. R. & Mastepanov, M. Moisture effects on temperature sensitivity of CO2 exchange in a subarctic heath ecosystem. Biogeochemistry 70, 315–330 (2004).

Schob, C., Kammer, P. M., Choler, P. & Veit, H. Small-scale plant species distribution in snowbeds and its sensitivity to climate change. Plant Ecology 200, 91–104 (2009).

Gough, L., Shaver, G. R., Carroll, J., Royer, D. L. & Laundre, J. A. Vascular plant species richness in Alaskan arctic tundra: The importance of soil pH. Journal of Ecology 88, 54–66 (2000).

Le Roux, P. C., Aalto, J. & Luoto, M. Soil moisture’s underestimated role in climate change impact modelling in low-energy systems. Global Change Biology 19, 2965–2975 (2013).

Grogan, P. & Jonasson, S. Temperature and substrate controls on intra-annual variation in ecosystem respiration in two subarctic vegetation types. Global Change Biology 11, 465–475 (2005).

Read, D. J., Leake, J. R. & Perez-Moreno, J. Mycorrhizal fungi as drivers of ecosystem processes in heathland and boreal forest biomes. Canadian Journal of Botany-Revue Canadienne De Botanique 82, 1243–1263 (2004).

Newsham, K. K., Frankland, J. C., Boddy, L. & Ineson, P. Effects of dry-deposited sulfur-dioxide on fungal decomposition of angiosperm tree leaf litter. 1. Changes in communities of fungal saprotrophs. New Phytologist 122, 97–110 (1992).

Jumpponen, A., Jones, K. L. & Blair, J. Vertical distribution of fungal communities in tallgrass prairie soil. Mycologia 102, 1027–1041 (2010).

Tedersoo, L. et al. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 346, 1256688 (2014).

Timling, I., Walker, D. A., Nusbaum, C., Lennon, N. J. & Taylor, D. L. Rich and cold: Diversity, distribution and drivers of fungal communities in patterned-ground ecosystems of the North American Arctic. Molecular Ecology 23, 3258–3272 (2014).

Robroek, B. J. M. et al. Peatland vascular plant functional types affect methane dynamics by altering microbial community structure. Journal of Ecology 103, 925–934 (2015).

Schadt, C. W., Martin, A. P., Lipson, D. A. & Schmidt, S. K. Seasonal dynamics of previously unknown fungal lineages in tundra soils. Science 301, 1359–1361 (2003).

Schmidt, S. K. & Lipson, D. A. Microbial growth under the snow: Implications for nutrient and allelochemical availability in temperate soils. Plant and Soil 259, 1–7 (2004).

Tybirk, K. et al. Nordic empetrum dominated ecosystems: Function and susceptibility to environmental changes. Ambio 29, 90–97 (2000).

Allison, S. D. Soil minerals and humic acids alter enzyme stability: Implications for ecosystem processes. Biogeochemistry 81, 361–373 (2006).

Baldrian, P. Fungal laccases - occurrence and properties. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 30, 215–242 (2006).

Rosling, A. et al. Archaeorhizomycetes: Unearthing an ancient class of ubiquitous soil fungi. Science 333, 876–879 (2011).

Hambleton, S. & Sigler, L. Meliniomyces, a new anamorph genus for root-associated fungi with phylogenetic affinities to Rhizoscyphus ericae (Hymenoscyphus ericae), leotiomycetes. Studies in Mycology 53, 1–27 (2005).

Karlsen, S. R., Jepsen, J. U., Odland, A., Ims, R. A. & Elvebakk, A. Outbreaks by canopy-feeding geometrid moth cause state-dependent shifts in understorey plant communities. Oecologia 173, 859–870 (2013).

Post, E. & Pedersen, C. Opposing plant community responses to warming with and without herbivores. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 105, 12353–12358 (2008).

Neuvonen, S., Niemelä, P. & Virtanen, T. Climatic change and insect outbreaks in boreal forests: the role of winter temperatures. Ecological Bulletins 47, 63–67 (1999).

Chapin, F. S. et al. Global change and the boreal forest: thresholds, shifting states or gradual change? Ambio 33, 361–365 (2004).

Weintraub, M. N. & Schimel, J. P. Nitrogen cycling and the spread of shrubs control changes in the carbon balance of arctic tundra ecosystems. BioScience 55, 408–415 (2005).

Cappelen, J. et al. eds. Danmarks Klima 2011 med Tórshavn, Færøerne og Nuuk, Grønland. Teknisk rapport 12-01 (Danish Meteorological Institute, 2012).

Forchhammer, M. C., Rasch, M. & Rysgaard, S. Nuuk basic - a conceptual framework for monitoring climate effects and feedback in arctic ecosystems. In: Jensen LM, Rasch M, eds Nuuk Ecological Research Operations, 1st Annual Report, 2007 (Danish Polar Center, 2008).

Molau, U. & Mølgaard, P. eds International Tundra Experiment, ITEX Manual (Danish Polar Centre, 1996).

Bokhorst, S. et al. Variable temperature effects of Open Top Chambers at polar and alpine sites explained by irradiance and snow depth. Global Change Biology 19, 64–74 (2013).

Havstrom, M., Callaghan, T. V. & Jonasson, S. Differential growth-responses of cassiope-tetragona, an arctic dwarf-shrub, to environmental perturbations among 3 contrasting high sites and sub-arctic sites. Oikos 66, 389–402 (1993).

Aastrup, P. et al. Conceptual Design and Sampling Procedures of the Biological Programme of Nuukbasic (National Environmental Research Institute, 2009).

Jonasson, S., Michelsen, A., Schmidt, I. K., Nielsen, E. V. & Callaghan, T. V. Microbial biomass C, N and P in two arctic soils and responses to addition of NPK fertilizer and sugar: Implications for plant nutrient uptake. Oecologia 106, 507–515 (1996).

Michelsen, A. et al. Differential responses of grass and a dwarf shrub to long-term changes in soil microbial biomass c, n and p following factorial addition of npk fertilizer, fungicide and labile carbon to a heath. New Phytologist 143, 523–538 (1999).

Van der Wal, A., Van Veen, J. A., Pijl, A. S., Summerbell, R. C. & De Boer, W. Constraints on development of fungal biomass and decomposition processes during restoration of arable sandy soils. Soil Biology & Biochemistry 38, 2890–2902 (2006).

White, T. J., Bruns, T. D., Lee, S. B. & Taylor, J. W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal rna genes for phylogenetics in PCR Protocols - a Guide to Methods and Applications (eds Innis, M. A., Gelfand, D. H., Sninsky, J. J. & White, T. J.) 315–222 (Academic Press, 1990).

Ihrmark, K. et al. New primers to amplify the fungal ITS2 region - evaluation by 454-sequencing of artificial and natural communities. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 82, 666–677 (2012).

Fierer, N., Jackson, J. A., Vilgalys, R. & Jackson, R. B. Assessment of soil microbial community structure by use of taxon-specific quantitative PCR assays. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 71, 4117–4120 (2005).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. Qiime allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature Methods 7, 335–336 (2010).

Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than blast. Bioinformatics 26, 2460–2461 (2010).

Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M. & Cole, J. R. Naive bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rrna sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 73, 5261–5267 (2007).

Abarenkov, K. et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi - recent updates and future perspectives. New Phytologist 186, 281–285 (2010).

R Development Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing Vienna, R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2012).

Dollive, S. et al. A tool kit for quantifying eukaryotic rRNA gene sequences from human microbiome samples. Genome Biology 13, R60 (2012).

Dray, S. & Dufour, A. B. The ade4 package: implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. Journal of Statistical Software 22, 1–20 (2007).

Oksanen, J. et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.0-6 (http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan) (2013).

Juggins, S. Rioja: Analysis of Quaternary Science Data, R Package Version 0.8-5 (http://cran.r-project.org/package=rioja) (2012).

Parks, D. H., Tyson, G. W., Hugenholtz, P. & Beiko, R. G. STAMP: Statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics 30, 3123–3124 (2014).

Ramette, A. Multivariate analyses in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 62, 142–160 (2007).

Šmilauer P. & Lepš J. Multivariate Analysis of Ecological Data Using CANOCO 5 (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at Greenland Institute of Natural Resources for providing good logistic facilities for the field work. Karin Vestberg, Inês Marques Nunes, Anette Hørdum Løth, Ida Vedel-Petersen and Gosha Sylvester for excellent assistance and method development. Data from the Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring Programme were provided by the Aarhus University, Denmark, in collaboration with Greenland Institute of Natural Resources. Finally, we gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Danish National Research Foundation, grant CENPERM DNRF100.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B.D. and A.P. designed the study. M.B.D., M.K., P.B., H.R.P., M.L. and J.N. did field work, M.B.D. did lab work, M.B.D., A.B., M.L. and M.S.H. did data analysis. M.B.D., M.S.H. and A.P. wrote the paper in collaboration with all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dahl, M.B., Priemé, A., Brejnrod, A. et al. Warming, shading and a moth outbreak reduce tundra carbon sink strength dramatically by changing plant cover and soil microbial activity. Sci Rep 7, 16035 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16007-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16007-y

This article is cited by

-

Influences of summer warming and nutrient availability on Salix glauca L. growth in Greenland along an ice to sea gradient

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Effects of shade stress on turfgrasses morphophysiology and rhizosphere soil bacterial communities

BMC Plant Biology (2020)

-

Moth Outbreaks Reduce Decomposition in Subarctic Forest Soils

Ecosystems (2020)

-

Fast response of fungal and prokaryotic communities to climate change manipulation in two contrasting tundra soils

Environmental Microbiome (2019)

-

Different Degrees of Niche Differentiation for Bacteria, Fungi, and Myxomycetes Within an Elevational Transect in the German Alps

Microbial Ecology (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.