Abstract

The precise timing and sequence of changes in expression of key genes and proteins during human sex-differentiation and onset of steroidogenesis was evaluated by whole-genome expression in 67 first trimester human embryonic and fetal ovaries and testis and confirmed by qPCR and immunohistochemistry (IHC). SRY/SOX9 expression initiated in testis around day 40 pc, followed by initiation of AMH and steroidogenic genes required for androgen production at day 53 pc. In ovaries, gene expression of RSPO1, LIN28, FOXL2, WNT2B, and ETV5, were significantly higher than in testis, whereas GLI1 was significantly higher in testis than ovaries. Gene expression was confirmed by IHC for GAGE, SOX9, AMH, CYP17A1, LIN28, WNT2B, ETV5 and GLI1. Gene expression was not associated with the maternal smoking habits. Collectively, a precise temporal determination of changes in expression of key genes involved in human sex-differentiation is defined, with identification of new genes of potential importance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gonadal sex-differentiation has been extensively studied in animal models but the precise timing of genetic events leading to proper development and sex-differentiation in humans is still uncertain. Significant information has been obtained in mice studies and similar mechanisms during sex differentiation are seen1. However, increasing evidence suggest that inter-species differences exist in the mechanisms of sex differentiation and that studies of human material is essential to verify results from other species2,3,4,5,6,7. A number of studies have suggested that fetal exposure to environmental pollutants, including maternal cigarette smoking, compromise germ cell number and potentially future fertility8,9,10,11,12, highlighting the events underlying gonadal differentiation as essential for understanding how external factors may affect gonadal development. In murine studies, several genes, including the Wilms tumor suppressor gene (WT1), steroidogenic factor 1 (SF1) and the Lim homeobox protein gene (LIM1) are necessary for the development of the bi-potential gonad prior to sex-differentiation13,14. Expression of these genes in human gonads is not clarified.

It was long held that sex-differentiation into testis required the expression of specific genes, while their absence would result in development of an ovary. It is now clear that gonadal sex is determined by antagonistic interactions between ovarian and testicular pathways15,16. In humans, the gonads are populated by primordial germ cells (PGCs), deriving from the yolk sac wall early in week five post conception (pc)17,18, with sex differentiation initiating around week six pc18. Somatic cell lines derive from the mesonephros and in females also from the ovarian surface epithelium19,20. In mammals, the crucial step towards differentiation into testis depends on the activation of the sex determining region on the Y chromosome (SRY), in which mutations lead to sex reversal2,21,22,23,24. In rodents, expression of Sry initiates a cascade of downstream signalling through the direct regulation of Sry-related HMG-Box gene 9 (Sox9). This promotes differentiation of the supporting cell precursors into Sertoli cells synthesising anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH)25,26,27. Several of the genes known to be essential for sex determination are highly conserved in mammals including human and mouse: WT-128,29,30, SF-130,31,32, SOX92,3,33, AMH34,35, whereas mutations for instance in the DAX1 gene lead to adrenal hypoplasia and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in humans36, with no effect on gonadal development and spermatogenesis in murine Dax1 null mutation37. It has been suggested that the mutant mouse may not be a complete null mutant or that Dax1 acts differently in mouse and human38. Inter-species differences have also been seen in the SRY gene. Human SRY transcripts and protein are persistent in low levels throughout the embryonic period3, whereas in the mouse Sry is expressed in a peak initiating differentiation39. Further neither human SRY or SOX9 transgenes are able to substitute for their mouse paralogs in transgene experiments4, supporting the inter-species differences. The SRY-related HMG-Box gene 17 (SOX17) has been described as an important regulator of germ cell specification in the human gonad only5,40. The pluripotent transcription factor OCT4 have recently been reported to be essential for blastocyst formation in humans – not in mice, suggesting an earlier and different role of OCT4 in human blastocysts compared to mice7.

In human testis, Leydig cell differentiation is dependent of the establishment of the sex cords and the first Leydig cells can be recognized at the end of week 9 pc18,41 simultaneous with the first testosterone production42, suggesting that the crucial events initiating steroidogenesis has taken place at this time, though the exact timing of the steroidogenic initiation is unknown. In human females, absence of SRY alongside expression of ovary-determining-genes such as Wnt Family Member 4 (WNT4), roof plate-specific spondin-1 (RSPO1) and forkhead box L2 (FOXL2) appear important for ovarian differentiation43. However, most of the experimental basis derives from mouse knockout models, with supporting information from genetic analysis of individuals with disorders of sexual development43,44.

Comprehensive analysis of gene expression in normal human gonads from the embryonic and early fetal stage has been limited44,45,46. No studies has yet addressed the precise timing and sequence of changes in expression of key genes and proteins at the time of sex differentiation and related that to subsequent events in germ cell and somatic cell maturation.

The aim of the present study was to analyse whole-genome gene expression in human male and female gonads aged 40 to 73 days pc. This period covers sex differentiation, testicular cord formation, and the testicular onset of steroidogenesis, with contemporaneous changes in the ovary.

Materials and Methods

A total of 67 first-trimester human embryonic and fetal gonads aged 40–73 days pc were included. Global gene expression was performed in 46 gonads (27 males, 19 females) by HTA-2.0 microarray analysis (Supp. Table 1). In 13 cases two gonads from the same embryo were obtained; in these cases one gonad was included in the microarray analysis while the other was used for qPCR validation. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses were performed at 8 embryonic and fetal gonads of both sexes.

Participating women

All participants were healthy women aged 18–47 years (mean ± SEM, 26.0 ± 1.0). All samples were obtained from legal elective abortions before gestational week 12 and all appeared morphologically normal. Exclusion criteria included age below 18 years, chronic disease, requiring an interpreter, and pregnancies with known disorders. All participants received oral and written information and gave their informed consent. Participants answered a questionnaire concerning their lifestyle during the pregnancy, including smoking and drinking habits. (Supp. Table 2). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and was approved by ‘The Scientific Ethical Committee for the Capital Region’ [KF (01) 258206].

Human embryonic and fetal tissues

Samples were obtained following surgical abortion at Skejby University Hospital. One ovary (73 days pc) was obtained from the archives at the University of Copenhagen. Embryonic and fetal age was determined by crown-rump length measured by ultrasound in utero. The genetic sex were determined by gonadal morphology and confirmed by PCR47.

Tissue processing and RNA extraction

Within minutes after the surgical procedure the aborted tissue was dissected under a stereomicroscope and the gonads were isolated from mesonephros. Gonads for IHC were fixed in Bouins solution and processed for histology. Gonads for gene analysis were incubated in RNAlater® (Sigma-Aldrich, Copenhagen, Denmark) for 5 min and stored at −80 °C. Prior to RNA isolation the samples were homogenized in a TissueLyser II at 4 °C (Qiagen, Copenhagen, Denmark) in 1.0 mL TRI Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 × 30 seconds at 15 Hz, using 0.3 mm. stainless steel beads. Each sample was further homogenized by adding 200 µl chloroform followed by vigorously shaking for 15 seconds followed by incubation at room temperature for 2–3 min. Samples were centrifuged through MaxTract High Density tubes (cat. No.: 129056, Qiagen) at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The further processing of the RNA containing supernatants were processed according to48. Median RIN was 9.3, range (2.4–10.0).

Microarray analysis

RNA samples were amplified and labelled using the Ovation Pico WTA v.2 RNA Amplification System according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Nugen, San Carlos, CA, USA). First strand cDNA was prepared from 50 ng of total RNA using a unique first strand DNA/RNA chimeric primer mix and reverse transcriptase (RT). Fragmentation of the mRNA within the cDNA/mRNA complex created priming sites for DNA polymerase to synthesize a second cDNA strand, which was used in the following single primer isothermal amplification (SPIA) step, in which the process of SPIA DNA/RNA primer binding, DNA replication, strand displacement and RNA cleavage was repeated to produce cDNA. Single stand cDNA was fragmented and biotin-labelled using the Encore Biotin Module (Nugen, San Carlos, CA, USA) before hybridization to the Human Transcriptome Array 2.0 GeneChip® (HTA 2.0) (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The arrays were washed and stained with phycoerythrin conjugated streptavidin (SAPE) using the Affymetrix Fluidics Station® 450, and further scanned in the Affymetrix GeneArray® 2500 scanner to generate fluorescent images, as described in the Affymetrix GeneChip® protocol. Cell intensity files (CEL files) were generated in the GeneChip® Command Console® Software (AGCC) (Affymetrix). The data was normalized and modelled using the RMA (Robust Multichip Average). The resulting expression matrix was pre-filtered according to Bourgon and colleagues49 by independent filtering of log2 values above 2.1 in one of the sexes in order to allow detection of sex dimorphic gene expressions and remove genes expressed below background. Only functionally annotated genes were included in the further analysis. Log2 expression between 2.1 and 5 was defined as genes expressed in a compartment of cells and log2 above 5 as genes being expressed in either all cells or abundantly in a subset of cells.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from whole homogenized embryonic and fetal gonads using TRI Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich,) and converted to first-strand cDNA by the use of the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufactures instructions. Samples were kept on ice at all times. Gene expression was determined by quantitative real-time PCR with the TaqMan® detection system as previously described48, using probes ids: SRY, #Hs00976796_s1, SOX-9, #Hs01001343_g1; CYP11A1, #Hs00167984_m1; STAR, #Hs00986559_g1; LIN28A, #Hs00702808_s1. Human glyceraldehyde 3-phosphatdehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as endogen control (probe id. No.: 433764 F). All samples were normalized to GAPDH and the relative expression was quantified according to the Comparative CT Method50.

Germ cell density

The germ cell density (i.e. number of germ cells per mm3) in embryonic and fetal gonads was calculated from our previously published data on gonadal germ cell numbers8,9. The germ cell densities were measured in gonads, which had or had not been exposed to maternal cigarette smoking.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Five μm serial sections were de-paraffinated in xylene, rehydrated in ethanol before antigen retrieval in Tris-egtazic acid (TEG-buffer) (10 mM Tris, 0.5 mM egtazic acid, pH 9) or citrate buffer (10 mM sodium citrate, pH 6) for 20 minutes. Endogen activity was inhibited with 1.5% peroxidase for 10 minutes, followed by one hour inhibition of unspecific binding with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma Aldrich). Sections were incubated with primary antibodies for one hour at room temperature (Table 1). GLI1 and ETV5 were incubated over night at 4 °C. Secondary antibodies used were rabbit-anti-mouse-HRP (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark, 1:100) and goat-anti-rabbit (Zymed, California, US 1:100) and visualised with 3.3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB + , Dako, 1:100).

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6.07 program (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA, USA) and the R program together with RStudio, version 0.99.473 (R software, Boston, Massachusetts, USA). Significance level was defined as a probability lower than 0.05 (p < 0.05). For each gene of interest data were analysed as fitting a linear or quadric expression pattern, for males and females separately. Differences in gene expression between sexes were further analysed with a linear or quadric model according to the results from the initial test. A Spearman’s rank test was used to evaluate whether gene expressions correlated with age. To compare characteristics from smoking versus non-smoking women, an unpaired parametric t-test was used when the parameters were normally distributed (e.g. age and BMI); when the parameters were not normally distributed, an unpaired non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was used (e.g. smoking).

Results

A total 46 human fetal gonads (27 males and 19 females) aged 40–67 days (mean ± SEM, 53.1 ± 1.1) were evaluated by global gene expression analysis. Further, 13 gonads were included for qPCR validation and 8 gonads were included for IHC.

Array gene expression

A total of 70,500 transcripts were analysed, including control, coding, non-coding and normalization genes. A total of 67,525 transcribed clusters were found, with 26,800 coding genes of which annotated genes extracted via the Qlucore Omics Explorer software (Qlucore.com). A sex dimorphic expression was detected in 319 genes (fold change >2.0, false discovery rate p-value < 0.05) (Supp. Figure 1). A total of 32 new and known genes associated with early gonadal development and sex-differentiation, including genes not previously described, were selected based on the expression level for further analysis and mapping.

Expression of genes determining development of the bi-potential gonad

WT1 and SF1 were highly expressed in gonads irrespective of sex. The WT1 gene was continuously expressed in ovaries whereas expression in testis decreased significantly over time (Fig. 1, Table 2). In contrast, SF1 was expressed at a constant level irrespective of sex and age (Fig. 1, Table 2).

Expression of SRY and SOX

In testis, SRY expression peaked around day 44 pc where after expression steadily decreased to base level around day 60 pc; SRY was not expressed in ovaries (Fig. 2, Table 2, Supp. Figure 2). In testis, SOX9 gene expression increased to a plateau around day 48 and was expressed significantly higher in testis than ovary (p < 0.0001); median SOX9 log2 expression in females and males: 4.8 and 7.3, respectively (Fig. 3, Table 2). In testis, SOX10 was expressed at significantly lower levels than SOX9 (p < 0.0001, median SOX10 log2 expression: 5.0) and SOX8 at even lower levels (median SOX8 log2 expression: 4.3) (Fig. 3, Table 2). Interestingly, SOX10 was significantly higher expressed in males than females (p < 0.0001, median SOX10 log2 in females: 4.6), whereas SOX17 expression was higher in females than males (p < 0.0344, median SOX17 log2 expression in females and males: 5.2 and 5.0, respectively) (Fig. 3, Table 2).

Expression of new sex dimorphic genes (GLI1, PTCH1, WNT2B and ETV5)

During mammalian embryogenesis Hedgehog (Hh) signalling regulates cell differentiation and is in mice important for Leydig cell differentiation51. Gene expression of the Hh receptor protein patched homolog 1 (PTCH1) and the transcription factor glioma-associated oncogene homologue (GLI1) was significantly higher expressed in testis than ovary and an inverse correlation with age was found for both males and females (Fig. 2, Table 2). The Hh ligands: Desert (DHH), Indian (IHH), and Sonic (SHH) were expressed at a constant level (range: log2 3.5–4.5) with no sex dimorphism (data not shown). Surprisingly, there was no significant difference between sexes in WNT4 expression and no correlation with age (Table 2), while WNT2B was significantly higher expressed in ovary than in testis and showed a significant positive correlation with age (Fig. 2, Table 2). RSPO1 and FOXL2 were also expressed significantly higher in ovary compared to testis, and the expression of RSPO1 was positively correlated with age (Fig. 2, Table 2). In the ovary, ETS Variant 5 (ETV5) expression was significantly higher than in testis and was positively correlated with age (Fig. 2, Table 2).

Expression of AMH

The microarray probes which covered the AMH gene also included the microRNA Mir4321, therefore no valid gene expression data on AMH was available from the microarray data. Therefore qPCR was used to evaluate AMH expression, where the probe detected a unique region of AMH excluding the mir-region. The expression of AMH was evaluated in all 46 gonadal samples; of these samples one result failed and two were outliers for no obvious reason, which were excluded (Fig. 2). In testis, AMH was highly expressed and positively correlated with age, whereas in ovary no expression was detected (Fig. 2, Table 2). In contrast, there was higher expression of AMHR in ovary than testis, with no correlation with age of either sex (Fig. 2, Table 2).

Expression of germ cell marker genes

The specific germ cell markers tyrosine-protein kinase (KIT), octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT4) and LIN28, together with the somatic-expressed KIT ligand (KITLG), was significantly higher expressed in ovary compared to testis and a positive correlation with age was found for KIT, KITLG, and OCT4 for both sexes (Fig. 4A, Table 2). The expression of the cancer/testis antigens GAGE10 and GAGE12B was significantly positively correlated with age in testis but no correlation was found in ovary, and there was no significant difference in expression between sexes (Table 2).

Gene expression of germ cell markers in testis and ovaries aged 40–68 days pc (A). The primordial germ cells (PGCs) density (i.e. PGCs per mm3) in testis and ovaries aged 35–68 days pc (B). Note the expression pattern of OCT4 and LIN28A reflect the PGC density pattern. Red represents female, blue represent males.

Germ cell density

Germ cell density (germ cells per mm3) was calculated from our previously published studies (29 females, 26 males)8,9, demonstrating a significantly higher germ cell density (p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.6403) in females than in males. A Spearman correlation test found a significant positive correlation between germ cell number and fetal age (females p < 0.0001, CI [0.725–0.939]; males p < 0.0001, CI [0.767–0.956]) and between germ cell density and fetal age (females p < 0.0001, CI [0.462–0.859]; males p < 0.0009, CI [0.284–0.812]). The pattern for each sex fitted a linear model better than a quadric model (Fig. 4B). The germ cell density pattern mirrored the mRNA expression pattern for KIT, OCT4, and LIN28A, confirming these genes are reliable germ cell markers (Fig. 4A,B).

Expression of genes essential in steroidogenesis

The steroidogenic genes POR, STAR, CYP11A1, CYP17A1, HSD3β2, HSD17β3, HSD17β7, and LHCGR were all expressed at higher levels in testis compared to ovary and all showed a characteristic increase in expression in testis around day 53 pc while no increase was observed in the ovary (Fig. 5, Table 2). HSD3β1 was hardly expressed in either sexes (mean log2 exp < 3.1 for both), whereas HSD3β2 expression was significantly higher in testis than in ovary (Fig. 5, Table 2). The array was able to identify 11 isoforms of HSD17β, and expression of HSD17β1/β4/β8/β10/β11/β12 was confirmed (log2: 4.5–7.0) in both testis and ovary. HSD17β3 and HSD17β7 were more abundantly expressed in testis as compared to ovary (Table 2), while HSD17- β2/β6/β13 was not expressed (data not shown). A simple linear – or quadric model described the data statistically equally well.

Gene expression of steroidogenic factors in testis and ovaries aged 40–68 days pc. All presented genes were significantly higher expressed in testis than ovaries. Further, a characteristic increase in expression was seen in testis around day 53 pc for several genes. Red represents females, blue represent males.

Expression of the estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ

The estrogen receptors α and β (ERα and ERβ) were continuously equally expressed in gonads of both sexes with ERα being significantly higher expressed than ERβ (mean log2 expression ERα: 5.0 and ERβ: 3.0) with no significant difference between sexes and no correlation with age (Table 2).

No effect of maternal smoking on embryonic and fetal gonadal gene expression

Half of both male and female gonads originated from mothers who smoked during their pregnancy (Supp. Table 1). To evaluate possible confounding effects of maternal lifestyle on gene expression, differences between smokers and non-smokers with respect to other lifestyle parameters were examined; however, there were no significant differences (Supp. Table 2). Further, there was no significant change in the expression (defined as a fold change ≥1.5) of any annotated genes (p > 0.05) between gonads prenatally exposed to maternal cigarette smoke and non-exposed gonads irrespective of sex.

Confirmation of array data with qPCR

In 13 cases (6 females and 7 males) both fetal gonads were obtained. In these cases one gonad was included in the microarray analysis and one used for validation by qPCR analysis. The relative mRNA expression of SRY, SOX9, STAR, CYP11A1, and LIN28A were analyzed by qPCR, confirming the expression pattern found in the microarray analysis, with significantly different expression of SRY, SOX9, and CYP11A1 LIN28 between sexes and borderline significant different expression of STAR (Sup. Figure 2). Data are presented as mean value of duplicate measurements including standard error of means.

Expression cut-off

The cut-off for valid log2 intensities was determined by the qPCR analysis of the transcription factor SRY on the Y chromosome, which is expected not to be present in females. By microarray analysis SRY was detected at relatively low intensities: testis (median log2: 3.4) and ovaries (median log2: 2.1), which reflect a fold change of 2.51. The cut-off intensity for the microarray, validated by the qPCR results, was therefore defined as log2 = 2.1. In the microarray relatively low log2 SRY intensity was seen in testis, which can be attributed to the fact that entire gonads were included – not specific cell types – which may dilute the measured expression intensity. QPCR analysis in relation to endogenous GAPDH confirmed the results obtained by microarray (Supp. Figure 2).

IHC staining

GAGE and LIN28 protein expression in germ cells

GAGE was detected in the nucleus of a subset of the germ cells in gonads of both sexes across the age range 45–73 days pc (Figs 6 and 7). LIN28 was also detected in germ cells in gonads of both sexes aged 45–73 days pc, with a cytoplasmic distribution.

Immunohistochemical detection of prominent markers in human embryonic and fetal testis aged 48–64 days pc (week 6–9 pc). GAGE and LIN28 were detected in germ cells. AMH and SOX9 were detected in Sertoli cells. CYP17A1 was detected in Leydig cells from day 54 pc. WNT2B was detected in Sertoli cells in week 6–7 changing to Leydig cells in week 8–9. GLI1 was detected in testicular germ cells, Sertoli and Leydig cells. ETV5 showed a relatively low general expression in testis, with germ cells staining more intense than somatic cells. G = germ cell; S = Sertoli cells, L = Leydig cells; so = somatic cells.

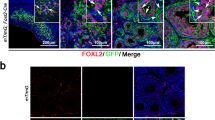

Immunohistochemical detection of specific markers in human embryonic and fetal ovary aged 45–73 days pc (week 6–10 pc). GAGE and LIN28 were detected in germ cells. AMH, SOX9, and CYP17A1 were not detected in ovaries. WNT2B was detected in ovarian somatic cells with an accumulation to epithelial cells and a faction of germ cells. GLI1 was generally expressed in the ovary and in the mesonephritic tublues without detectin in the mesenchymal stroma. ETV5 showed a relatively low general expression in ovary, with germ cells staining more intense than somatic cells. In 6 weeks ovary EVT5 was compartmentalized with strong expression in the ovarian surface epithelium with a decreasing staining intensity towards the mesonephros. ETV5 was also detected in mesonephritic tubuli. G = germ cell; so = somatic cells, m = mesonephros, tu = tubuli.

AMH and SOX9 proteins expressed in Sertoli cells

The SOX9 transcription factor was detected in Sertoli cell nuclei, and AMH was detected in Sertoli cell cytoplasm in testes ages 48–64 days (Fig. 6). AMH and SOX9 were not detected in any ovaries (Fig. 7).

CYP17A1 expressed in Leydig cells

CYP17A1 was detected in some Leydig cells outside testicular cords from day 54, becoming more widely expressed in Leydig cells from testis aged 60–64 days (Fig. 6). No immunohistochemical staining of CYP17A1 was detected in any of the ovaries (Fig. 7).

WNT2B, GLI1, and ETV5 expressed in ovary and testis

In testes aged 48–54 days pc WNT2B, GLI1, and ETV5 was confined to testicular cords, whereas at later gestational age (day 60–64 pc) WNT2B and GLI1 was also detected in Leydig cells (Fig. 6). In contrast, ETV5 remained expressed within testis cords at day 60–64 with increasing intensity in germ cells (Fig. 6). In ovaries, WNT2B was detected in somatic cells particularly in ovarian surface epithelium between days 45–73 (Fig. 7). GLI1 and ETV5 were detected in mesonephritic tubuli and in the ovary with no staining in the mesenchymal stroma (Fig. 7). Further, at day 45 ETV5 showed a characteristic increase in staining intensity from medulla towards cortex and surface epithelium.

Discussion

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study to provide a detailed mapping of the temporal expression of key regulatory genes governing sex-differentiation and initiation of steroidogenesis in the human embryonic and fetal gonad in both males and females. Additionally, new genes (i.e. GLI1, ETV1 and WNT2B), of potential importance in human sex-differentiation and development have been identified. The present study is, however, descriptive and the associations found between gene expression, sex and age may not reflect functional mechanisms.

In human testis sex-differentiation initiates as early as day 40–44 pc with expression of SRY, closely followed by expression of SOX9, while both are absent in ovaries. Previously, SRY expression has been detected at week 9 followed by a drop in week 1146, which corresponds to transient murine Sry gene expression at initiation of sex-differentiation39,52,53. The present data expand previous findings by advancing the onset of SRY expression to as early as day 40 pc (5½ weeks), enforcing its prominent role in initiation of sex-differentiation. The expression of SRY (median log2: 3.4) was relatively low compared to other evaluated genes, probably reflecting that SRY serves as a transcription factor where only little activity is sufficient to initiate the downstream signalling and is only expressed in Sertoli cells. Expression of SOX9 was detected at both gene and protein level from day 48 pc, advancing the previously reported onset with approximately one week46,54. Collectively this suggests that human sex-differentiation start around one week earlier than previously described.

The gene expression pattern of fetal mice gonads during sex differentiation determined by microarray analysis resemble the patterns of the present study55: The undifferentiated gonad (11.5 dpc in mouse and 44 dpc in human) express a number of genes with similar expression in both sexes. Sex differentiation is initiated with the expression of SRY and SOX9 (mouse 12.5 dpc, human 44–48 dpc) followed by expression of AMH (mouse 16.5 dpc, human 50–60 dpc) and the genes involved in the steroidogenesis (mouse 14.5–18.5 dpc, human 54 dpc). In mouse, genes involved in ovarian meiosis are expressed already at day 14.555 whereas the human ovary do not initiate meiosis before week 10 pc56, which relatively is later than mice and beyond the evaluated period of the present study.

Sox9 targets Etv5, which is expressed by Sertoli cells and play a role in maintaining the spermatogonial stem cell niche in fetal mice testis, but not in fetal ovary57,58. In neonatal mice Etv5 is also expressed in germ cells and is essential for spermatogonial proliferation58. In the adult mouse ovary Etv5 protein are localized to the granulosa, further females deficient for Etv5 are infertile suggesting Etv5 to be essential for the ovarian function later in life59,60. The present study found ETV5 gene expression in both sexes with significantly higher expression in ovary, suggesting an earlier ovarian role in human than mice. At the protein level ETV5 showed a relatively low general expression in both testis and ovary, with testis staining both germ cells and Sertoli cells as seen in mice. Surprisingly, germ cells of both sexes stained more intense than somatic cells, suggesting that in humans ETV5 may play a direct role in early germ cell survival within the germ cell niece in both sexes, though further studies is needed to clarify this.

The present study found Hedgehog gene expression of the PTCH1 receptor and the transcription factor GLI1 in both sexes with significantly higher expression in testis than ovary. This sexual dimorphic expression of Ptch1 and Gli1 has previously been reported in fetal mice models51,61,62 with Gli1 and ptch1 being present fetal testis63 but absent in fetal ovary until the time of birth64. In mice, the dimorphic expression may reflect that Gli1 is essential for Leydig cell differentiation in the early fetal testis but are not essential in the ovary before after birth when theca cells are established63,64. In fetal mice testis, it has been shown that Sertoli cell-derived Hh-signalling induce an activation of the interstitial cells, which becomes Gli1 positive and may act as progenitors to two cell lines: 1) Steroid producing fetal Leydig cells and 2) non-steroidogenic progenitor cells, which differentiate into adult Leydig cells63. In the neonatal mouse ovary gene expression of Ptch1 and Gli1 has been detected in granulosa and theca cells of primary follicles – not in primordial, suggesting a role of Hh signalling in the communication between granulosa cells and theca cells in growing follicles65,66, a role in proliferation and androstenedione production has also been suggested66,67. The present study detect GLI1 in both testis and ovaries, with more intense staining in Leydig cells, confirming a potential role for GLI1 in human fetal Leydig cell differentiation as seen in mice. In contrast to mice, GLI1 protein is detected in the human fetal ovary suggesting that Hh mediated somatic cell communication initiates already in fetal life in humans, which is first seen after birth in mice. The first follicles occur in humans already in fetal life whereas in mice follicle formation is not seen until after birth68 which may support the suggestion of a general earlier activity and cell-cell-communication in the human ovary. The general staining of both ETV5 and GLI1 was specific to the gonad and mesonephritic tubuli with no staining in the mesenchymal stroma, suggesting these proteins may play a role in the early gonadal development of both sexes though a specific role cannot be pinpointed. It would have been fortunate to have qPCR analysis on all new genes; however this was not possible due to limited access to human embryonic and fetal material. The expressions of genes included in qPCR analysis were in good agreement with the expression detected by microarray analysis, suggesting compliance between the analysis methods.

Sertoli cells expressed detectable levels of AMH from day 44 pc, both detected by IHC and gene expression assays. As expected, AMH was undetectable in ovary, but surprisingly AMHR2 was highly expressed in both sexes.

The present study identified onset of human testicular steroidogenesis to take place around day 53 pc (week 7½), with the key steroidogenic enzymes showing synchronous and very marked increase in gene expression. This was further supported by IHC-detection of CYP17A1-producing Leydig cells from day 54 pc and by qPCR analysis of STAR and CYP11A1. Testosterone synthesis has previously been measured in fetal testes from week 10 pc and onwards69 and the present study therefore advances initiation of steroidogenesis in testis by approximately two weeks. Elevated expression of some steroidogenic enzymes in fetal testis compared to ovary aged 9–20 weeks pc has been described46. Since the microarray data is based on gene expression in all cells of the entire gonad it is noteworthy that the first steroid-producing Leydig cells detected at day 54 contribute sufficiently for detection among the total gonadal mRNA pool. Expression of steroidogenic genes was low in the ovary, irrespective of age.

The family of HSD17β enzymes catalyze the conversion of 17-keto/hydroxyl steroids. We found high expression of 6 HSD17β -isoforms in gonads of both sexes, while HSD17β3 and HSD17β7 were more highly expressed in testis than ovary, suggesting that these isotypes may be important for early male steroidogenesis. In mice testis, Hsd17β1 and hsd17β3 are expressed already in fetal life at high levels70, while in rats they are only expressed in adulthood (reviewed by Griswold and Behringer, 2009). In the present study, HSD17β3 is suggested the dominant isotype with an expression significantly higher in testis than ovary, whereas the HSD17β1 is less expressed with no difference between sexes. HSD17β3 has previously been detected in human fetal testis aged 9–20 weeks46 and has also been suggested the dominant isotype in adult human testis71,72. In embryonic and fetal testis, the regulation of HSD17β may differ between rodents and humans. Furthermore, we found the LH/chorionic gonadotrophin receptor (LHCGR) mRNA to be expressed in the human fetal testis from day 53, which extent findings by Macdonald and collegues73, who did not detect LHCGR protein until 12 gestational weeks and co-localization with HSD3β was not seen before 20 weeks’ gestation, suggesting that in first trimester steroidogenesis may not be mediated via LHCGR73.

Expression of aromatase (CYP19A1) was below detection limit in both sexes at these early developmental stages. Later in fetal life (week 14–22) aromatase has been detected in Sertoli, Leydig, and germ cells, but with no expression in week 3574. Estrogens have been suggested to block proliferation of the precursor Leydig cells75 and since proliferation of the testicular cells is high at gestational weeks 13–1976 it has been speculated that estrogens function in exactly this time frame as a regulator of precursor Leydig cell proliferation and differentiation, thereby affecting testosterone production77. Surprisingly, we find both ERα and ERβ to be continuously expressed in both sexes with expression of ERα being significantly higher than ERβ. This is in contrast to previous findings where ERβ but not ERα was detected in testes aged 14–22 weeks74. This may indicate a shift in estrogen receptor isoform expression in males from first to second trimester. In second trimester ovaries gene expression of both ERα and ERβ has been detected45. Taken together, steroidogenic enzymes are present in the embryonic male testis from day 53 pc both at mRNA and protein level advancing initiation of steroidogenesis with approximately one week, whereas aromatization does not initiate until later in fetal life, beyond the period evaluated in this study.

Among the key regulators of female sex-differentiation is RSPO1, an activator of the canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway opposing testis formation, with WNT4 as the key ligand44,78. Throughout the period of sex-differentiation significantly higher RSPO1 expression was detected in ovary compared to testis44, confirming previous findings and supporting an important role in female sex-differentiation. WNT4 may also be a crucial female determinant: Wnt4 deficiency in female mice caused partial female-to-male sex reversal79 and inhibits endothelial and steroidogenic cell migration80, with disrupted initiation of meiosis81. Wnt4 may also have a testicular function in Sertoli cell organization and differentiation80. The present study demonstrates constitutive expression of WNT4 from day 40–68 pc in the evaluated period irrespective of sex. Interestingly, a significantly higher level of WNT2B was detected in ovary compared to testis, suggesting a role of WNT2B in the human fetal ovary. Expression of WNT2B was by IHC also detected in somatic cells of testis and in ovaries with a stronger staining intensity in ovaries. Interestingly, WNT2B was compartmentalized with strong protein expression in the ovarian surface epithelium, a pattern which previously have been identified in the ovarian surface epithelium of adult rats82, and suggest a local regulation of tissue modelling in the ovary already in embryonic and fetal life. The characteristic increase in staining intensity towards the ovarian surface epithelium may suggest that WNT2B play a role in the survival and migration of the pre-granulosa cells, which have been suggested to originate from the ovarian surface epithelium wherefrom they populate the ovary19,20.

FOXL2 is a highly conserved gene expressed during sex determination in pre-granulosa cells that later populate the ovarian medulla83,84. In mammals, FOXL2 can activate aromatase transcription during ovarian development and may prevent differentiation into testes78. Previous studies have detected FOXL2 gene expression in human fetal ovaries aged 8–19 gestation with increasing expression from week 8 to 1484. The present study detected FOXL2 gene expression in ovaries from around day 44 pc (week 6), exactly at the initiation of the ovarian sex differentiation. FOXL2 was significantly higher expressed in ovaries than testis, suggesting that FOXL2 may be essential for proper differentiation of the human ovary.

Before sex differentiation, from day 40 pc, the embryonic gonads expressed high levels of WT1 and SF1. SF1 remained constant throughout the evaluated period with the expression of WT1 being lower in testis compared to ovaries. The sex dimorphic expression of WT1 may be due to a dilution factor. These genes have previously been described to play essential roles in early murine gonadal development and in development of kidneys and adrenal glands of both sexes13,28,29,31,85,86. In fetal male mice, Sf1 expression persists in Leydig cells and in testicular cords after sex-differentiation indicating that Sf1 may play a developmental role beyond the expression of steroidogenic enzymes85. In humans, heterozygous inactivating mutations in SF1 have been associated with male to female sex reversal and adrenal failure, indicating that SF1 is also essential for normal development in humans87.

The germ cell markers KIT (and its somatic-expressed ligand KITLG), OCT4, and LIN28A were more highly expressed in ovary compared to testis. This is consistent with the presence of more than twice as many germ cells in the ovary compared to the testis at 63 days pc8,9,88, confirming the validity of these markers as a surrogate for germ cell number over this developmental period. Interestingly, in testis expression of KITLG decreased over time while that of the KIT receptor continued to increase. KIT receptor has been detected in a fraction of testicular germ cells aged 7–17 weeks89.

Maternal cigarette smoking had previously been reported to cause a negative effect on the number of germ cells in first trimester embryos and fetuses8, an effect that persists through the second trimester90. We were unable to reveal any difference in gene expression between smoke exposed and non-exposed embryos and fetuses, which may reflect that gonads from smokers overall contain fewer cells but with the same relative contribution of different cell types compared to non-smokers, or because the present study evaluated gene expression in entire gonads – not in specific cells types, which then may dilute out differences.

Collectively the present findings provide a detailed temporal roadmap of changes in expression of key genes in human fetal gonads during sex-differentiation. Testis differentiation initiates already day 40 pc with expression of SRY/SOX9, followed by expression of the steroidogenic genes at day 53 pc. GLI1, ETV1, and WNT2B are newly identified genes, which may play a role in early human gonadal development, though further functional studies are needed to elucidate their potential roles.

Ethical approval

‘The Scientific Ethical Committee for the Capital Region’ [KF (01) 258206] gave approval for this study. All participants gave informed consent before taking part and have given written consent for their data being included in publications. We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

References

Breschi, A., Gingeras, T. R. & Guigó, R. Comparative transcriptomics in human and mouse. Nat. Publ. Gr. 18 (2017).

Koopman, P. Sry and Sox9: Mammalian testis-determining genes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 55, 839–856 (1999).

Hanley, N. et al. Gene expression pattern SRY, SOX9, and DAX1 expression patterns during human sex determination and gonadal development. Mech. Dev. 91, 403–407 (2000).

Wunderle, V. M., Critcher, R., Hastie, N., Goodfellow, P. N. & Schedl, A. Deletion of long-range regulatory elements upstream of SOX9 causes campomelic dysplasia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10649–54 (1998).

Irie, N. et al. SOX17 Is a Critical Specifier of Human Primordial Germ Cell Fate. Cell 160, 253–268 (2015).

Jiménez, R. Ovarian Organogenesis in Mammals: Mice Cannot Tell Us Everything. Sex Dev 3, 291–301 (2009).

Fogarty, N. M. E. et al. Genome editing reveals a role for OCT4 in human embryogenesis. Nature (2017).

Mamsen, L. S. et al. Cigarette smoking during early pregnancy reduces the number of embryonic germ and somatic cells. Hum. Reprod. 25, 2755–2761 (2010).

Lutterodt, M. C. et al. The number of oogonia and somatic cells in the human female embryo and fetus in relation to whether or not exposed to maternal cigarette smoking. Hum. Reprod. 24, 2558–2566 (2009).

Storgaard, L. et al. Does smoking during pregnancy affect sons’ sperm counts? Epidemiology 14, 278–86 (2003).

Ramlau-Hansen, C. H. et al. Is prenatal exposure to tobacco smoking a cause of poor semen quality? A follow-up study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 165, 1372–1379 (2007).

Jensen, M., Mabeck, L., Toft, G., Thulstrup, A. & Bonde, J. Lower sperm counts following prenatal tobacco exposure. Hum. Reprod. 20, 2559–2566 (2005).

Parker, K. L., Schimmer, B. P. & Schedl, A. Genes essential for early events in gonadal development. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 55, 831–8 (1999).

Migeon, C. J. & Wisniewski, aB. Human sex differentiation: from transcription factors to gender. Horm. Res. 53, 111–119 (2000).

Piprek, R. P. Genetic mechanisms underlying male sex determination in mammals. J. Appl. Genet. 50, 347–360 (2009).

Kobayashi, A. & Behringer, R. R. Developmental genetics of the female reproductive tract in mammals. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4, 969–980 (2003).

Witschi, E. Migration of the germ cells of human embryos from the yolk sac to the primitive gonadal folds. ContribEmbryol 209, 67–80 (1948).

Byskov, A. G. Differentiation of Mammalian Embryonic Gonad. PhysRev 66, 71–106 (1986).

Hummitzsch, K. et al. A new model of development of the mammalian ovary and follicles. PLoS One 8, e55578 (2013).

Maheshwari, A. & Fowler, P. A. Primordial follicular assembly in humans – revisited. Zygote C 16, 285–296 (2017).

Jost, A., Vigier, B., Prépin, J. & Perchellet, J. P. Studies on sex differentiation in mammals. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 29, 1–41 (1973).

Koopman, P., Gubbay, J., Vivian, N., Goodfellow, P. & Lovell-Badge, R. Male development of chromosomally female mice transgenic for Sry. Nature 351, 117–21 (1991).

Ostrer, H. Sexual differentiation. Semin. Reprod. Med. 18, 41–9 (2000).

Sinclair, A. H. Human sex determination. J. Exp. Zool. 281, 501–5 (1998).

She, Z.-Y. & Yang, W.-X. Sry and SoxE genes: How they participate in mammalian sex determination and gonadal development? Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 63, 13–22 (2016).

Magre, S. Sertoli cell differentiation and testicular morphogenesis in the rat fetus. Arch. Anat. Microsc. Morphol. Exp. 74, 64–68 (1991).

Rossi, P., Dolci, S., Albanesi, C., Grimaldi, P. & Geremia, R. Direct evidence that the mouse sex-determining gene Sry is expressed in the somatic cells of male fetal gonads and in the germ cell line in the adult testis. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 34, 369–73 (1993).

Pelletier, J. et al. WT1 mutations contribute to abnormal genital system development and hereditary Wilms’ tumour. Nature 353, 431–4 (1991).

Kreidberg, J. A. et al. WT-1 is required for early kidney development. Cell 74, 679–691 (1993).

Hanley, N. A. et al. Expression of steroidogenic factor 1 and Wilms’ tumour 1 during early human gonadal development and sex determination. Mech. Dev. 87, 175–80 (1999).

Luo, X., Ikeda, Y. & Parker, K. L. A cell-specific nuclear receptor is essential for adrenal and gonadal development and sexual differentiation. Cell 77, 481–90 (1994).

Sadovsky, Y. et al. Mice deficient in the orphan receptor steroidogenic factor 1 lack adrenal glands and gonads but express P450 side-chain-cleavage enzyme in the placenta and have normal embryonic serum levels of corticosteroids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 10939–43 (1995).

Morais da Silva, S. et al. Sox9 expression during gonadal development implies a conserved role for the gene in testis differentiation in mammals and birds. Nat. Genet. 14, 62–68 (1996).

Josso, N., Racine, C., di Clemente, N., Rey, R. & Xavier, F. The role of anti-Müllerian hormone in gonadal development. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 145, 3–7 (1998).

Josso, N. et al. Anti-müllerian hormone in early human development. Early Hum. Dev. 33, 91–9 (1993).

Muscatelli, F. et al. Mutations in the DAX-1 gene give rise to both X-linked adrenal hypoplasia congenita and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Nature 372, 672–676 (1994).

Yu, R. N., Ito, M., Saunders, T. L., Camper, S. A. & Jameson, J. L. Role of Ahch in gonadal development and gametogenesis. Nat. Genet. 20, 353–357 (1998).

Capel, B. The battle of the sexes. Mech. Dev. 92, 89–103 (2000).

Jeske, Y. W. A., Bowles, J., Greenfield, A. & Koopman, P. Expression of a linear Sry transcript in the mouse genital ridge. Nat. Genet 10, 480–482 (1995).

de Jong, J. et al. Differential expression of SOX17 and SOX2 in germ cells and stem cells has biological and clinical implications. J. Pathol. 215, 21–30 (2008).

Voutilainen, R. Differentiation of the fetal gonad. Horm. Res. 38(Suppl 2), 66–71 (1992).

Sitteri, P. K. & Wilson, J. D. Testosterone Formation and Metabolism During Male Sexual Differentiation in the Human Embryo. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 38, 113–125 (1974).

Biason-Lauber, A. WNT4, RSPO1, and FOXL2 in sex development. Semin. Reprod. Med. 30, 387–395 (2012).

Tomaselli, S. et al. Human RSPO1/R-spondin1 Is Expressed during Early Ovary Development and Augments β-Catenin Signaling. PLoS One 6, e16366 (2011).

Fowler, P. A. et al. Development of Steroid Signaling Pathways during Primordial Follicle Formation in the Human Fetal Ovary. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, 1754–1762 (2011).

Houmard, B. et al. Global gene expression in the human fetal testis and ovary. Biol. Reprod. 81, 438–43 (2009).

Nakahori, Y., Hamano, K., Iwaya, M. & Nakagome, Y. Sex identification by polymerase chain reaction using X-Y homologous primer. Am. J. Med. Genet. 39, 472–473 (1991).

Kristensen, S. G. et al. Expression of TGF-beta superfamily growth factors, their receptors, the associated SMADs and antagonists in five isolated size-matched populations of pre-antral follicles from normal human ovaries. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 20, 293–308 (2014).

Bourgon, R., Gentleman, R. & Huber, W. Independent filtering increases detection power for high-throughput experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 9546–51 (2010).

Schmittgen, T. D. & Livak, K. J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–8 (2008).

Yao, H. H.-C., Whoriskey, W. & Blanche, C. Desert Hedgehog/Patched 1 signaling specifies fetal Leydig cell fate in testis organogenesis. Genes Dev. 16, 1433–1440 (2002).

Koopman, P., Münsterberg, A., Capel, B., Vivian, N. & Lovell-Badge, R. Expression of a candidate sex-determining gene during mouse testis differentiation. Nature 348, 450–452 (1990).

Hacker, A., Capel, B., Goodfellow, P. & Lovell-Badge, R. Expression of Sry, the mouse sex determining gene. Development 121, 1603–14 (1995).

Ostrer, H., Huang, H. Y., Masch, R. J. & Shapiro, E. A Cellular Study of Human Testis Development. Sex Dev 1, 286–292 (2007).

Small, C. L., Shima, J. E., Uzumcu, M., Skinner, M. K. & Griswold, M. D. Profiling gene expression during the differentiation and development of the murine embryonic gonad. Biol. Reprod. 72, 492–501 (2005).

Byskov, A. G. In Germ Cell and Fertiliztion (eds Austin, C. R. & Short, R.). 1–17 (Cambridge University Press, 1982).

Alankarage, D. et al. SOX9 regulates expression of the male fertility gene Ets variant factor 5 (ETV5) during mammalian sex development. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 79, 41–51 (2016).

Tyagi, G. et al. Loss of Etv5 Decreases Proliferation and RET Levels in Neonatal Mouse Testicular Germ Cells and Causes an Abnormal First Wave of Spermatogenesis. Biol. Reprod. 81, 258–266 (2009).

Eo, J. et al. Complex ovarian defects lead to infertility in Etv52/2 female mice. Mol Hum Rep 17, 568–576 (2011).

Eo, J., Han, K. M., Murphy, K., Song, H. & Lim, H. J. Etv5, an ETS transcription factor, is expressed in granulosa and cumulus cells and serves as a transcriptional regulator of the cyclooxygenase-2. J. Endocrinol. 198, 281–90 (2008).

Yao, H. H. & Capel, B. Disruption of Testis Cords by Cyclopamine or Forskolin Reveals Independent Cellular Pathways in Testis Organogenesis. Dev Biol 246, 356–365 (2002).

Barsoum, I. & Yao, H. H. C. Redundant and Differential Roles of Transcription Factors Gli1 and Gli2 in the Development of Mouse Fetal Leydig Cells. Biol. Reprod. 84, 894–899 (2011).

Liu, C., Rodriguez, K. & Yao, H.-C. H. Mapping lineage progression of somatic progenitor cells in the mouse fetal testis. Developmen 143, 3700–3710 (2016).

Liu, C., Peng, J., Matzuk, M. M. & Yao, H. H. C. Lineage Specification of Ovarian Theca Cells Requires Multi- Cellular Interactions via Oocyte and Granulosa Cells. Nat Commun 6 (2015).

Wijgerde, M., Ooms, M., Hoogerbrugge, J. W. & Grootegoed, J. A. Hedgehog Signaling in Mouse Ovary: Indian Hedgehog and Desert Hedgehog from Granulosa Cells Induce Target Gene Expression in Developing Theca Cells. Endocrinology 146, 3558–3566 (2005).

Russell, M. C., Cowan, R. G., Harman, R. M., Walker, A. L. & Quirk, S. M. The Hedgehog Signaling Pathway in the Mouse Ovary. Biol. Reprod. 77, 226–236 (2007).

Spicer, L. J. et al. The hedgehog-patched signaling pathway and function in the mammalian ovary: a novel role for hedgehog proteins in stimulating proliferation and steroidogenesis of theca cells. Reproduction 138, 329–339 (2009).

Byskov, A. G. & Høyer, P. E. In The Physiology of Reproduction (eds Knobil, E. & Neill, J. D.) 487–540 (Raven Press, 1994).

Faiman, C., Winter, J. S. & Reyes, F. Endocrinology of the fetal testis. (Raven Press, 1981).

Sha, J., Baker, P. & O’Shaughnessy, P. J. Both reductive forms of 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (types 1 and 3) are expressed during development in the mouse testis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 222, 90–4 (1996).

Griswold, S. L. & Behringer, R. R. Fetal Leydig cell origin and development. Sex Dev. 3, 1–15 (2009).

Baker, P. J., Sha, J. H. & O’Shaughnessy, P. J. Localisation and regulation of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 3 mRNA during development in the mouse testis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 133, 127–133 (1997).

Macdonald, J., Smith, L. B., Anderson, R. A. & Mitchell, R. T. Spatiotemporal profiling of luteinising hormone/human choriogonadotropin receptor in the human fetal testis. Lancet 387, S74 (2016).

Boukari, K. et al. Human fetal testis: source of estrogen and target of estrogen action. Hum. Reprod. 22, 1885–1892 (2007).

Abney, T. O. & Myers, R. B. 17 beta-estradiol inhibition of Leydig cell regeneration in the ethane dimethylsulfonate-treated mature rat. J. Androl. 12, 295–304 (1991).

Murray, T. J., Fowler, P. A., Abramovich, D. R., Haites, N. & Lea, R. G. Human Fetal Testis: Second Trimester Proliferative and Steroidogenic Capacities1. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 85, 4812–4817 (2000).

Huhtaniemi, I., Leinonen, P., Hammond, G. L. & Vihko, R. Effect of oestrogen treatment on testicular LH/HCG receptors and endogenous steroids in prostatic cancer patients. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 13, 561–8 (1980).

Pannetier, M., Chassot, A.-A., Chaboissier, M.-C. & Pailhoux, E. Involvement of FOXL2 and RSPO1 in Ovarian Determination, Development, and Maintenance in Mammals. Sex. Dev. 10, 167–184 (2016).

McMahon, A. P., Vainio, S., Heikkilä, M., Kispert, A. & Chin, N. Female development in mammals is regulated by Wnt-4 signalling. Nature 397, 405–409 (1999).

Jeays-Ward, K., Dandonneau, M. & Swain, A. Wnt4 is required for proper male as well as female sexual development. Dev. Biol. 276, 431–40 (2004).

Naillat, F. et al. Wnt4/5a signalling coordinates cell adhesion and entry into meiosis during presumptive ovarian follicle development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 1539–1550 (2010).

Ricken, A., Lochhead, P., Kontogiannea, M. & Farookhi, R. Wnt Signaling in the Ovary: Identification and Compartmentalized Expression of wnt-2, wnt-2b, and Frizzled-4 mRNAs. Endocrinology 143, 2741–9 (2002).

Loffler, K. A., Zarkower, D. & Koopman, P. Etiology of ovarian failure in blepharophimosis ptosis epicanthus inversus syndrome: FOXL2 is a conserved, early-acting gene in vertebrate ovarian development. Endocrinology 144, 3237–43 (2003).

Duffin, K., Bayne, Ra. L., Childs, aJ., Collins, C. & Anderson, R. A. The forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 is expressed in somatic cells of the human ovary prior to follicle formation. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 15, 771–777 (2009).

Parker, K. L. & Schimmer, B. P. Steroidogenic factor 1: a key determinant of endocrine development and function. Endocr. Rev. 18, 361–377 (1997).

Lala, D. S., Rice, D. A. & Parker, K. L. Steroidogenic factor I, a key regulator of steroidogenic enzyme expression, is the mouse homolog of fushi tarazu-factor I. Mol. Endocrinol. 6, 1249–58 (1992).

Achermann, J. C., Ito, M., Ito, M., Hindmarsh, P. C. & Jameson, J. L. A mutation in the gene encoding steroidogenic factor-1 causes XY sex reversal and adrenal failure in humans. Nat. Genet. 22, 125–6 (1999).

Mamsen, L. S., Lutterodt, M. C., Andersen, E. W., Byskov, aG. & Andersen, C. Y. Germ cell numbers in human embryonic and fetal gonads during the first two trimesters of pregnancy: analysis of six published studies. Hum. Reprod. 26, 2140–2145 (2011).

Gkountela, S. et al. The ontogeny of cKIT + human primordial germ cells: A resource for human germ line reprogramming, imprint erasure and in vitro differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 15, 113–122 (2013).

Anderson, R. A. et al. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by a component of cigarette smoke reduces germ cell proliferation in the human fetal ovary. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 20, 42–8 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank Henriette Gram Johanson and Susanne Smed for excellent technical assistance. The Research Fund at Rigshospitalet, the EU interregional ReproUnion project, and Aase and Einar Danielsens Fund supported this study but had no role in the study design, collection and analysis of data, data interpretation or in writing the report. The corresponding author had full access to all data presented in the study and had the final responsibility for the decision to submit this paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.S.M. was responsible for writing the paper, collected the human fetal gonads, interpreted data, and performed the statistical analysis and prepared tables and figures. E.H.E. and R.H.O. conducted the scanning during the evacuation procedure. R.B. interpreted the microarray data and assisted with the statistical analysis. A.L. assisted collecting human fetal tissue and placenta samples. E.E. was responsible for the surgical procedure of terminating pregnancies and consulted the participating women prior to the operation for completion of questionnaires and obtained the blood samples. S.G.K. performed the qPCR analysis. R.A.A. interpreted data and drafted the paper. C.Y.A. interpreted data, drafted the paper and was responsible for the study design.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mamsen, L.S., Ernst, E.H., Borup, R. et al. Temporal expression pattern of genes during the period of sex differentiation in human embryonic gonads. Sci Rep 7, 15961 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15931-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15931-3

This article is cited by

-

A conserved NR5A1-responsive enhancer regulates SRY in testis-determination

Nature Communications (2024)

-

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated activation of NR5A1 steers female human embryonic stem cell-derived bipotential gonadal-like cells towards a steroidogenic cell fate

Journal of Ovarian Research (2023)

-

Human development and reproduction in space—a European perspective

npj Microgravity (2023)

-

Modeling Human Gonad Development in Organoids

Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine (2022)

-

Novel variants in the stem cell niche factor WNT2B define the disease phenotype as a congenital enteropathy with ocular dysgenesis

European Journal of Human Genetics (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.