Abstract

Occupying a position between entanglement and Bell nonlocality, Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) steering has attracted increasing attention in recent years. Many criteria have been proposed and experimentally implemented to characterize EPR-steering. Nevertheless, only a few results are available to quantify steerability using analytical results. In this work, we propose a method for quantifying the steerability in two-qubit quantum states in the two-setting EPR-steering scenario, using the connection between joint measurability and steerability. We derive an analytical formula for the steerability of a class of X-states. The sufficient and necessary conditions for two-setting EPR-steering are presented. Based on these results, a class of asymmetric states, namely, one-way steerable states, are obtained.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum nonlocality, EPR-steering and quantum entanglement are important quantum correlations. EPR-steering, which was originally presented by Schrodinger in the context of the famous Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) paradox1, lies between quantum nonlocality and quantum entanglement, which means that one observer, by performing a local measurement on one’s subsystem, can nonlocally steer the state of the other subsystem. Recently EPR-steering was reformulated by Wiseman et al. who described the hierarchy among Bell nonlocality, EPR-steering and quantum entanglement2. EPR-steering has been shown to be advantageous for quantum tasks such as randomness generation, subchannel discrimination, quantum information processing and one-sided device-independent processing in quantum key distributions3,4,5,6,7.

Many efforts have been made to detect and measure EPR-steering. Some steering inequalities based on uncertainty relations8,9,10,11,12,13, inequalities based on steering witnesses and the Clauser-Horne-Shimony-Holt (CHSH)-like inequality, and geometric Bell-like inequalities et al.14,15,16,17,18,19,20 are constructed to diagnose the steerability, are usually necessary conditions. In addition to inequalities, all-versus-nothing proof without inequalities, were also presented to detect steerability21. However only a few methods are available to quantify EPR-steering based on maximal violation of steering inequalities22, steering weight23 and steering robustness. In these cases semi-definite programming is necessary to calculate the measures. Recently, the radius of a super quantum hidden state model was proposed to evaluate the steerability24 by finding the optimal super local hidden states. Nevertheless, it is formidably difficult to find the optimal super quantum hidden states. A critical radius was proposed via the geometrical method, and the critical radius of T-states was calculated explicitly25. The closed formulas for steering were derived in two- and three-measurement scenarios26, which is the case in which Alice and Bob are both allowed to measure the observables at their own sites. It has been proven that one-to-one mapping exists between the joint measurability and the steerability of any assemblage27,28,29,30. Using the connection between steering and joint measurability, the closed formula of the measure for two-setting EPR-steering of Bell-diagonal states was given31. However, for any two-qubit quantum states, one still lacks a closed formula for the steerability problem, even for a 2-setting scenario.

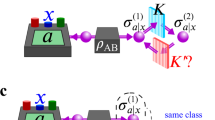

Different from Bell nonlocality and quantum entanglement, steering exhibits asymmetric features, as proposed by Wiseman et al.2. There exist quantum states \({\rho }_{AB}\), for which Alice can steer Bob’s state but Bob can not steer Alice’s state, or vice versa. This distinguishing feature could be useful for some one-way quantum information tasks such as quantum cryptography, but until recently only a few asymmetric states have been proposed and experimentally demonstrated24,32,33,34.

In this work, we investigate the analytical formula for quantification of EPR-steering and obtain the necessary and sufficient condition of steerability for a class of quantum states. The asymmetric feature of EPR-steering is also investigated.

Setting up the stage

Consider a bipartite qubit system \({\rho }_{AB}\) shared by Alice and Bob with reduced density states ρ A and ρ B . Alice performs positive-operator-valued measures (POVMs) \({{\rm{\Pi }}}_{\kappa |\overrightarrow{n}}\) on subsystem A, where \({{\rm{\Pi }}}_{\kappa |\overrightarrow{n}}=\frac{1}{2}({{\rm{I}}}_{2}+{(-\mathrm{1)}}^{\kappa }\overrightarrow{n}\cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma }),\) I2 is the identity matrix and \(\overrightarrow{\sigma }=({\sigma }_{x},{\sigma }_{y},{\sigma }_{z})\) are the Pauli matrices. Alice obtains the result \(\kappa \mathrm{\ (}\kappa =\mathrm{0,1)}\) when measuring along the direction \(\overrightarrow{n}\mathrm{.}\) Bob’s unnormalized conditional state is \({\tilde{\rho }}_{\kappa |\overrightarrow{n}}={{\rm{Tr}}}_{A}[{\rho }_{AB}({{\rm{\Pi }}}_{\kappa |\overrightarrow{n}}\otimes {{\rm{I}}}_{2})]\). Bob’s unconditional state \({\rho }_{B}={{\rm{Tr}}}_{A}{\rho }_{AB}=\sum _{\kappa }{\tilde{\rho }}_{\kappa |\overrightarrow{n}}\) remains unchanged under any measurement direction. A state assemblage \({\tilde{\rho }}_{\kappa |\overrightarrow{n}}\) is unsteerable if there exists a local hidden state model (LHSM) with the state ensemble of \({p}_{i}{\rho }_{i}\) satisfying \({\tilde{\rho }}_{\kappa |\overrightarrow{n}}=\sum _{i}P(\kappa |\overrightarrow{n},i){p}_{i}{\rho }_{i}\), where \({\rho }_{B}=\sum _{i}{p}_{i}{\rho }_{i}\) and \(\sum _{\kappa }P(\kappa |\overrightarrow{n},i)=1.\) The quantum state \({\rho }_{AB}\) is unsteerable from A to B if for all local POVMs, the state assemblages are all unsteerable. The quantum state ρ AB is steerable from A to B if there exist measurements in Alice’s case that produce an assemblage that demonstrates steerability.

The corresponding local hidden state model and the joint measurement observables are connected through \({O}_{\kappa |\overrightarrow{n}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{{\rho }_{B}}}{\tilde{\rho }}_{\kappa ,\overrightarrow{n}}\frac{1}{\sqrt{{\rho }_{B}}}\) and \({G}_{i}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{{\rho }_{B}}}{p}_{i}{\rho }_{i}\frac{1}{\sqrt{{\rho }_{B}}}\) by the one-to-one mapping between the joint measurement problem and the steerability problem, whenever ρ B is invertible27. The steerability can be detected through the joint measurability of the observables.

Two-setting steering scenario: Any two-qubit quantum state can be expressed by \({\rho }_{AB}=({{I}}_{4}+\overrightarrow{a}\cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma }\otimes \) \({{I}}_{2}+{{I}}_{2}\otimes \overrightarrow{b}\cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma }+\sum _{i}^{3}{c}_{i}{\sigma }_{i}\otimes {\sigma }_{i}\mathrm{)/4}\) under local unitary equivalence, where \(\overrightarrow{a},\overrightarrow{b},\overrightarrow{c}\in {R}^{3}\), \({\sigma }_{1}={\sigma }_{x}\), \({\sigma }_{2}={\sigma }_{y}\), \({\sigma }_{3}={\sigma }_{z}\), \(\overrightarrow{\sigma }=\{{\sigma }_{1},{\sigma }_{2},{\sigma }_{3}\}\), \(C={\rm{Diag}}\{{c}_{1},{c}_{2},{c}_{3}\}\) is the correlation matrix.

When Alice performs two sets of POVMs \({{\rm{\Pi }}}_{\kappa |{\overrightarrow{n}}_{i}}=({{I}}_{2}+{(-\mathrm{1)}}^{\kappa }{\overrightarrow{n}}_{i}\cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma }\mathrm{)/2}\) \((i=\mathrm{0,}\,\mathrm{1,}\,\kappa =\mathrm{0,}\,\mathrm{1)}\) on A with \({\overrightarrow{n}}_{i}=({\rm{s}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{n}}{\alpha }_{{\rm{i}}}{\rm{c}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{s}}{\beta }_{{\rm{i}}},{\rm{s}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{n}}{\alpha }_{{\rm{i}}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{n}}{\beta }_{{\rm{i}}},{\rm{c}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{s}}{\alpha }_{{\rm{i}}}),\) Bob’s unnormalized conditional states are \({\tilde{\rho }}_{\kappa |{\overrightarrow{n}}_{i}}={\rm{Tr}}[{\tilde{\rho }}_{\kappa |{\overrightarrow{n}}_{i}}]({{\rm{I}}}_{2}+\) \({(-\mathrm{1)}}^{\kappa }{\overrightarrow{s}}_{\kappa ,i}\cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma }\mathrm{)/2}\), where \({\rm{Tr}}[{\tilde{\rho }}_{\kappa |{\overrightarrow{n}}_{i}}]=\mathrm{(1}+{(-\mathrm{1)}}^{\kappa }\overrightarrow{a}\cdot {\overrightarrow{n}}_{i}\mathrm{)/2}\) and \({\overrightarrow{s}}_{\kappa ,i}=(\overrightarrow{b}+{(-\mathrm{1)}}^{\kappa }C\cdot {\overrightarrow{n}}_{i}\mathrm{)/(2}{\rm{Tr}}[{\tilde{\rho }}_{\kappa |{\overrightarrow{n}}_{i}}])\). When \(|b|\ne \mathrm{1,}\) the measurement assemblages are

where \({\overrightarrow{g}}_{i}=U\,{\overrightarrow{n}}_{i},\) \({x}_{i}=V\,{\overrightarrow{n}}_{i}\) with

and \(V=\frac{{\overrightarrow{a}}^{T}-{\overrightarrow{b}}^{T}C}{1-|b{|}^{2}}\mathrm{.}\) Thus, \({\{{\tilde{\rho }}_{\kappa |{\overrightarrow{n}}_{i}}\}}_{\kappa ,i}\) are unsteerable assemblages if and only if \({\{{O}_{\kappa }({x}_{i},{\overrightarrow{g}}_{i})\}}_{\kappa ,i}\) are jointly measurable35,36,37, namely,

where \({F}_{{x}_{i}}=\frac{1}{2}(\sqrt{{\mathrm{(1}+{x}_{i})}^{2}-{g}_{i}^{2}}+\sqrt{{\mathrm{(1}-{x}_{i})}^{2}-{g}_{i}^{2}}),\) \({g}_{i}=|{\overrightarrow{g}}_{i}\mathrm{|.}\)

(1) gives rise to the condition for Alice to steer Bob’s state. If Bob performs two sets of POVMs \({{\rm{\Pi }}}_{\kappa |{\overrightarrow{n}}_{i}}\) on his system to steer Alice’s state, the corresponding condition can be similarly written by changing \(\overrightarrow{a}\to \overrightarrow{b}\), \(\overrightarrow{b}\to \overrightarrow{a}\) and \(C\to {C}^{T}\) in (1).

However, it is generally quite difficult to address condition (1) and obtain explicit conditions to judge the steerability for an arbitrary given two-qubit state. For Bell-diagonal states, a necessary and sufficient condition of steerability has been derived from the relations between steerability and the joint measurability problem31. In the following, we study the steerability of any arbitrary given two-qubit states. We present analytical steerability conditions for classes of two-qubit X-state.

Results

Steerability of two-qubit states

First, based on the jointly measurable condition (1) of \({\{{O}_{\kappa }({x}_{i},{\overrightarrow{g}}_{i})\}}_{\kappa ,i}\) for the two-setting steering scenario, we define the steerability of two-qubit states \({\rho }_{AB}\) by the following

where \({S}_{1}=\mathrm{(1}-{F}_{{x}_{0}}^{2}-{F}_{{x}_{1}}^{2}\mathrm{)(1}-\frac{{x}_{0}^{2}}{{F}_{{x}_{0}}^{2}}-\frac{{x}_{1}^{2}}{{F}_{{x}_{1}}^{2}})\), \({S}_{2}={({\overrightarrow{g}}_{0}\cdot {\overrightarrow{g}}_{1}-{x}_{0}{x}_{1})}^{2}\), and the maximization runs over all of the measurements \({{\rm{\Pi }}}_{\kappa |{\overrightarrow{n}}_{i}}\), namely, over the parameters \({\alpha }_{i}\) and \({\beta }_{i}\), \(i=\mathrm{0,1}\). It is obvious that S lies between 0 and 1 and \({\rho }_{AB}\) is steerable if and only if \(S\, > \,0\).

For general two-qubit states, a global search can be used to obtain the global minimum values of S. The Matlab code is supplied in the supplementary material.

Due to the relationship between the joint measurements and steerability, local hidden states \({\tilde{\rho }}_{\kappa |{\overrightarrow{n}}_{i}}\) are represented as \(\sqrt{{\rho }_{B}}{G}_{\mu v}\sqrt{{\rho }_{B}}\) \((\mu =\pm \mathrm{1,}v=\pm \mathrm{1),}\) where \({G}_{\mu v}=\frac{1}{4}\mathrm{(1}+\mu {x}_{0}+v{x}_{1}+\mu vZ+(\mu v\overrightarrow{z}+\mu {\overrightarrow{g}}_{0}+v{\overrightarrow{g}}_{1})\overrightarrow{\sigma })\) which are all possible sets of four measurements satisfying the marginal constraints for any two jointly measurable observables \({\{{O}_{\kappa }({x}_{i},{\overrightarrow{g}}_{i})\}}_{\kappa ,i}\) 35,36,37. The steering radius \(R({\rho }_{AB})\) 24 can be calculated by optimizing \(\overrightarrow{z}\) and Z.

In the following, we analytically calculate the steerability S for some X-states \({\rho }_{X}\). We define a class of two-qubit X-states to be zero-states \({\rho }_{zero}\) if the X-states \({\rho }_{X}\) satisfy the condition that the maximum points (stationary points) of S 1 belong to the zero points of S 2 with respect to the measurement parameters α i and \({\beta }_{i},(i=\mathrm{1,2)}\).

For any two-qubit X-state, \({\rho }_{X}=\frac{1}{4}({{I}}_{4}+{a}_{3}{\sigma }_{3}\otimes {{I}}_{2}+{b}_{3}{{I}}_{2}\otimes {\sigma }_{3}+\sum _{i}^{3}{c}_{i}{\sigma }_{i}\otimes {\sigma }_{i})\), we have \(U={\rm{Diag}}\{{u}_{1},{u}_{2},{u}_{3}\},\) \(V\,=\,\mathrm{[0,}\,\mathrm{0,}\,{t}_{3}]\), where \({u}_{1}={c}_{1}/\sqrt{1-{b}_{3}^{2}}\), \({u}_{2}={c}_{2}/\sqrt{1-{b}_{3}^{2}}\), \({u}_{3}=({a}_{3}{b}_{3}-{c}_{3})/(-1+{b}_{3}^{2})\) and \({t}_{3}=({a}_{3}-{b}_{3}{c}_{3}\mathrm{)/}\) \(\mathrm{(1}-{b}_{3}^{2}\mathrm{).}\)We obtain the following results:

Theorem

. For the zero-states \({\rho }_{zero}\), the analytical formula of the steerability is given by

where \({{\rm{\Delta }}}_{1}={u}_{1}^{2}+{u}_{2}^{2}-\mathrm{1,}\) \({{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}=\frac{1}{2}[{u}_{1}^{2}({u}_{3}^{2}-{t}_{3}^{2})+{u}_{1}^{2}+{u}_{3}^{2}+{t}_{3}^{2}-1-\mathrm{(1}-{u}_{1}^{2})\sqrt{\mathrm{((1}-{t}_{3}{)}^{2}-{u}_{3}^{2}\mathrm{)((1}+{t}_{3}{)}^{2}-{u}_{3}^{2})}],\) \({{\rm{\Delta }}}_{3}=\frac{1}{2}[{u}_{2}^{2}({u}_{3}^{2}-{t}_{3}^{2})+{u}_{2}^{2}+{u}_{3}^{2}+{t}_{3}^{2}-1-\mathrm{(1}-{u}_{2}^{2})\times \) \(\sqrt{\mathrm{((1}-{t}_{3}{)}^{2}-{u}_{3}^{2}\mathrm{)((1}+{t}_{3}{)}^{2}-{u}_{3}^{2})}\mathrm{].}\) When \(S > \mathrm{0,}\) the optimal measurements that give rise to maximal S are \({\sigma }_{x}\) and \({\sigma }_{y}\) if \({{\rm{\Delta }}}_{1} > max\{{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2},{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{3}\mathrm{,0\},}\) \({\sigma }_{x}\) and \({\sigma }_{z}\) if \({{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2} > \,{\rm{\max }}\,\{{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{1},{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{3},\,\mathrm{0\},}\) and \({\sigma }_{y}\) and \({\sigma }_{z}\) if \({{\rm{\Delta }}}_{3} > max\{{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{1},{{\rm{\Delta }}}_{2}\mathrm{,0\}}\).

The proof is given in the supplementary material.

It is obvious that any X-state with \({t}_{3}=0\) belongs to \({\rho }_{zero}\), e.g., \(|\phi \rangle =a\mathrm{|00}\rangle +\sqrt{1-{a}^{2}}\mathrm{|11}\rangle \) \(\mathrm{(0} < |a| < \mathrm{1)}\) and the Bell-diagonal state \(\rho =\frac{1}{4}({\rm{I}}+{c}_{1}{\sigma }_{1}\otimes {\sigma }_{1}+{c}_{2}{\sigma }_{2}\otimes {\sigma }_{2}+{c}_{3}{\sigma }_{3}\otimes {\sigma }_{3})\) are all the zero states. For \(|\phi \rangle ,\) we have \(S=1\).

For the Bell-diagonal state, interestingly, the steerability \(S\) is given by the non-locality characterized by the maximal violation of the CHSH inequality. Let \({ {\mathcal B} }_{CHSH}\) denote the Bell operator for the CHSH inequality38, \({ {\mathcal B} }_{CHSH}={A}_{1}\otimes {B}_{1}+{A}_{1}\otimes {B}_{2}+{A}_{2}\otimes {B}_{1}-{A}_{2}\otimes {B}_{2}\), where \({A}_{i}={\overrightarrow{a}}_{i}\cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma }\), \({B}_{i}={\overrightarrow{b}}_{i}\cdot \overrightarrow{\sigma }\), \({\overrightarrow{a}}_{i}\) and \({\overrightarrow{b}}_{i}\), \(i=\mathrm{1,}\,2\), are unit vectors. Thus, the the maximal violation of the CHSH inequality is given by39

where \({\tau }_{1}\) and \({\tau }_{2}\) are the two largest eigenvalues of the matrix \({T}^{\dagger }T\), \(T\) is the matrix with entries \({T}_{\alpha \beta }=tr[\rho \,{\sigma }_{\alpha }\otimes {\sigma }_{\beta }]\), \(\alpha ,\,\beta \,=\,\mathrm{1,2,3}\), \(\dagger \) indicates transpose and conjugation. For the Bell-diagonal state, we have \(N=\) \(2\sqrt{{c}_{1}^{2}+{c}_{2}^{2}+{c}_{3}^{2}-\,{\rm{\min }}\,\{{c}_{1}^{2},{c}_{2}^{2},{c}_{3}^{2}\}}\). From (3), we find that the steerability of Bell-diagonal state is given by \(S=\frac{{N}^{2}}{4}-1\).

For \({t}_{3}\ne 0\), we give the explicit conditions of the zero states in the supplementary material.

In the following, we present the maximum value of the steerability S for a given N of \({\rho }_{zero}\).

Corollary 1

: For zero-states \({\rho }_{zero}\) with given N, \(0\le N\le 2\), we have \(S\le \frac{N}{2}\). Moreover, \(S=N\mathrm{/2}\) is attained when \({a}_{3}\,=\,1-{c}_{3}+{b}_{3},\) \({b}_{3}\to -\mathrm{1,}\) \({c}_{1}=\sqrt{\mathrm{(1}+{b}_{3})({c}_{3}-{b}_{3})},\) \({c}_{2}=-{c}_{1},\) i.e., \({\rho }_{zero}\) has the following form,

The following corollary gives the conditions at which we obtain the minimal value of S for a given N.

Corollary 2

: For zero-states \({\rho }_{zero}\) with given CHSH value N, S obtains the minimal value when \({a}_{3}\mathrm{=0}\) and \({b}_{3}\mathrm{=0}\) or \(|{a}_{3}+{b}_{3}|=\sqrt{{\mathrm{(1}+{c}_{3})}^{2}-{({c}_{1}-{c}_{2})}^{2}}\) or \(|{a}_{3}-{b}_{3}|=\sqrt{{\mathrm{(1}-{c}_{3})}^{2}-{({c}_{1}+{c}_{2})}^{2}}\).

The proofs of Corollary 1 and Corollary 2 are given in the supplementary material. In Fig. 1, we give a description for the boundaries of the steerability S for a given value of N. From Fig. 1, we observe that for any given N with \(0\le N\le 2\), the lower bound of S is always 0 and the upper bound of S is always less than 2 (light blue), and for \(N\mathrm{ > 2,}\) the lower bound of S is always greater than 0, and the upper bound of S is always 2 (dark blue).

For zero-states \({\rho }_{zero},\) the steering radius \(R({\rho }_{zero})\) can be obtained when Alice measures her qubit along the directions \({\sigma }_{x}\) and \({\sigma }_{y},\) or \({\sigma }_{x}\) and \({\sigma }_{z},\) or \({\sigma }_{y}\) and \({\sigma }_{z}\mathrm{.}\) Indeed, from the construction of joint measurements35, when Alice measures her qubit along the directions of \({\sigma }_{x}\) and \({\sigma }_{z},\) the local hidden states can be expressed as follows

where \({m}_{x}=\mu v({c}_{1}+\mu \sqrt{1-{b}_{3}^{2}}{z}_{1}),\) \({m}_{z}={b}_{3}+\mu {c}_{3}+v({z}_{3}+{b}_{3}Z),\) \(\mu =\pm \mathrm{1,}v=\pm 1.\) Therefore

where

It is not easy to calculate \(r{({\rho }_{zero})}_{xz}\) and \(r{({\rho }_{zero})}_{yz}\) analytically. We give the analytical results for \(R({\rho }_{zero})\) for some special states in the following.

Asymmetric two-setting EPR-steering

Different from Bell-nonlocality and quantum entanglement, EPR-steering has the asymmetric property of one-way EPR steering: Alice may steer Bob’s state but not vice versa. The demonstration of asymmetric steerability has practical implications in quantum communication networks40. Until now, only a few asymmetric steering states have been found24,32,33,34. In this work we present a class of asymmetric steering states of the form \({\rho }_{{X}_{0}}\) in (5).

If Alice performs measurements on her qubit, the steerability is given by \(S({\rho }_{{X}_{0}})=max\{\frac{2{c}_{3}-1-{b}_{3}}{1-{b}_{3}}\mathrm{,0\}}\) which approaches \({c}_{3}\) when \({b}_{3}\) approaches \(-1\) and \({c}_{3} > 0\). If Bob performs measurements on his qubit, the related steerability is given by the following

which is equal to zero as long as \(\mathrm{(1}+{b}_{3})({b}_{3}+{c}_{3})\le 0\). Therefore, when \(0 < {c}_{3} < -{b}_{3}\) and \({b}_{3}\to -\mathrm{1,}\) Alice can always steer Bob’s state, but Bob can never steer Alice’s state (see Fig. 2 for the asymmetric EPR-steering for \({b}_{3}=-0.999\)). We note that Alice can always steer Bob’s state, but Bob can not steer Alice’s state.

In the following subsection, we investigate the geometric features of the asymmetric steering state-\({\rho }_{{x}_{0}}\) in terms of the steering ellipsoid41. The steering ellipsoid of \({\rho }_{{X}_{0}}\) when Alice performs POVMs is quite different from that when Bob performs POVMs. The centre of the steering ellipsoid \({\varepsilon }_{B}\) for Alice performing POVMs on her qubit is \(\mathrm{(0,0,(}{b}_{3}-{a}_{3}{c}_{3}\mathrm{)/(1}-{a}_{3}^{2}))\), which goes to \(\mathrm{(0,0,}-\mathrm{1)}\) when \(b\to -\mathrm{1,}\) and the volume of the steering ellipsoid \({\varepsilon }_{B}\) is given as follows

In this case the steering ellipsoid is tangent to the Bloch sphere. The centre of the steering ellipsoid \({\varepsilon }_{A}\) for Bob performing POVMs on his qubit is

which goes to \(\mathrm{(1}-{c}_{3}\mathrm{)/2}\) when \({b}_{3}\to -1\). The volume of the steering ellipsoid \({\varepsilon }_{A}\) is given by the following

which goes to \(\frac{\pi {\mathrm{(1}+{c}_{3})}^{2}}{3}\) when \({b}_{3}\to -1\). The steering ellipsoid is also tangent to the Bloch sphere. In this case the ellipsoid shows some peculiar features, i.e., when \({b}_{3}\to -1\) and \({c}_{3}\to 0\), the ellipsoid \({\varepsilon }_{B}\) is nearly \(0\), but Alice can still steer Bob; however, when \({b}_{3}\to -1\) and \({c}_{3}\to -{b}_{3}\), the ellipsoid \({\varepsilon }_{A}\) is almost the entire Bloch sphere, but Bob can not steer Alice.

As a special case of \({\rho }_{{X}_{0}},\) we take \({a}_{3}=1-2\eta \mathrm{(1}-\chi ),\) \({b}_{3}=2\eta \chi -\mathrm{1,}\) \({c}_{3}=2\eta -\mathrm{1,}\) \({c}_{1}=-{c}_{2}=-2\eta \sqrt{\chi \mathrm{(1}-\chi )}\). The state has the following form,

From the theorem, we obtain the following when Alice measures her qubit,

The sufficient and necessary condition in the two-setting steering scenario is \(\eta \, > \,\mathrm{1/(2}-\chi )\) for Alice to steer Bob’s state. The corresponding optimal measurements are \({\sigma }_{x}\) and \({\sigma }_{y}\mathrm{.}\)

If Bob measures his qubit, the steerability is given by the following

The sufficient and necessary condition for Bob to steer Alice’s state is \(\eta \mathrm{ > 1/(1}+\chi )\). The related optimal measurements are \({\sigma }_{x}\) and \({\sigma }_{y}\mathrm{.}\) The asymmetric property in quantum steering given by this example is shown in Figs 3 and 4. The steering radius is \(\sqrt{1-4\eta \chi \mathrm{(1}-\eta \mathrm{(2}-\chi ))}\) when Alice measures her qubit, and \(\sqrt{1-4\eta \mathrm{(1}-\chi \mathrm{)(1}-\eta -\eta \chi )}\) when Bob measures his qubit.

Parameter region for which Alice (Bob) can steer Bob’s (Alice’s) state for the state \({W}_{\eta }^{\chi }\). In region I, Alice can steer Bob’s state, and Bob can also steer Alice’s state. In region II (III), Alice (Bob) can steer Bob’s (Alice’s) state, but Bob (Alice) can not steer Alice’s (Bob’s) state. In region IV, Alice can not steer Bob’s state, and Bob can not steer Alice’s state.

As another example showing the asymmetry of quantum steering, we consider the state \({W}_{V}^{\theta }\) 24,

where \(|{\psi }_{1}\rangle =\,\cos \,\theta \mathrm{|00}\rangle +\,\sin \,\theta \mathrm{|11}\rangle ,\) \(|{\psi }_{2}\rangle =\,\cos \,\theta \mathrm{|10}\rangle +\,\sin \,\theta \mathrm{|01}\rangle ,\) \(\theta \in \mathrm{(0,}\,\pi \mathrm{/2),}\,V\in \mathrm{[0,}\,\mathrm{1/2)}\cup \mathrm{(1/2,}\,\mathrm{1]}\). \({W}_{V}^{\theta }\) is a zero state. From our theorem, we know that when Alice performs measurements on her qubit, \(S({W}_{V}^{\theta })={\mathrm{(1}-2V)}^{2}\). The optimal measurements are \({\sigma }_{x},\) \({\sigma }_{y}\) or \({\sigma }_{x},\) \({\sigma }_{z}\mathrm{.}\) This state is always steerable for Alice except when \(V\mathrm{=1/2}\).

When Bob performs two projective measurements on his qubit, we have the following

The sufficient and necessary condition in the two-setting steering scenario for Bob to steer Alice’s state is \(|cos2\theta \mathrm{| < |2}V-\mathrm{1|}\), with the optimal measurements \({\sigma }_{x}\) and \({\sigma }_{y}\). For \({W}_{V}^{\theta },\) the corresponding steering radius is \(\sqrt{1+{\mathrm{(1}-2V)}^{2}{\sin }^{2}2\theta }\) when Alice measures her qubit, and \(\sqrt{{\mathrm{(1}-2V)}^{2}+{\sin }^{2}2\theta }\) when Bob measures his qubit. From Fig. 5 we observe that Alice can always steer Bob’s state except when \(V\mathrm{=1/2,}\) but Bob can steer Alice’s state only for some V depending on θ.

From our theorem, the analytical results of steerability can be obtained for more detailed zero states, and the asymmetric property of steering can be readily studied. In the following, we give two examples of symmetric two-setting EPR-steering.

Example 1

. The two-qubit nonmaximally entangled state mixed with colour noise,

where \(|\psi (\theta )\rangle =\,\cos \,\theta \mathrm{|00}\rangle +\,\sin \,\theta \mathrm{|11}\rangle \), \(\theta \in \mathrm{(0,}\pi \mathrm{/2)}\), \(V\in \mathrm{(0,1]}\). The steerability is given by \(S({\rho }_{{\rm{c}}n})={V}^{2}{\sin }^{2}2\theta \mathrm{/}\) \(\mathrm{(1}-{V}^{2}\,\cos \,2{\theta }^{2})\). Therefore, \({\rho }_{{\rm{c}}n}\) is steerable if and only if \(V{\rm{s}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{n}}2\theta \ne 0.\)

Example 2

. The generalized isotropic state, \({\rho }_{gi}=V|\psi (\theta )\rangle \langle \psi (\theta )|+\mathrm{(1}-V){\rm{I}}\mathrm{/4}\), where \(|\psi (\theta )\rangle =\,\cos \,\theta \mathrm{|00}\rangle +\) \(\sin \,\theta \mathrm{|11}\rangle \), \(\theta \in \mathrm{(0,}\pi \mathrm{/2)}\), \(V\in \mathrm{(0,1]}\). The state reduces to the usual isotropic state when \(\theta =\pi \mathrm{/4}\). According to our theorem, we obtain the analytical steerability of \({\rho }_{gi}\),

Hence, the sufficient and necessary condition of steerability is \(1+\mathrm{(1}-V)\sqrt{{\mathrm{(1}+V)}^{2}-4{V}^{2}{\cos }^{2}2\theta } < \) \({V}^{2}\mathrm{(1}+2{\sin }^{2}2\theta \mathrm{).}\)

Discussion

Based on the one-to-one correspondence between EPR-steering and joint measurability, we have investigated the steerability for any two-qubit system in the two-setting measurement scenario. The steerability we introduced is invariant under local unitary operations. The analytical formula for steerability has been derived for a class of X-states, and the sufficient and necessary conditions for two-setting EPR-steering have been presented. For general two-qubit states, it has been shown that the lower and upper bounds of steerability are explicitly connected to the non-locality of the states given by the CHSH values of maximal violation. Moreover, we have also presented a class of asymmetric steering states by investigating steerability with respect to the measurements from Alice’s and Bob’s sides. Our strategy might also be used to study the quantification of steerability for multi-setting scenarios, in particular, for three-setting scenarios for which the joint measurability problem of three qubit observables has already been investigated42,43. Our method might also be used in continuous variable steering, temporal and channel steering, for which the steerability of the state assemblages or the instrument assemblages can be connected to the incompatibility problems of the quantum measurement assemblages44,45. Hence, the steerability of the quantum states or the quantum channels might also be studied based on the corresponding measurement incompatibility problems.

References

Einstein, A., Podolsky, B. & Rosen, N. Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete? Phys. Rev. 47, 777–780 (1935).

Wiseman, H. M., Jones, S. J. & Doherty, A. C. Steering, Entanglement, Nonlocality, and the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Paradox. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 140402 (2007).

Law, Y. Z., Thinh, L. P., Bancal, J. D. & Scarani, V. Quantum randomness extraction for various levels of characterization of the devices. J. Phys. A 47, 42 (2014).

Piani, M. & Watrous, J. Necessary and Sufficient Quantum Information Characterization of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Steering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 060404 (2015).

Branciard, C. & Gisin, N. Quantifying the Nonlocality of Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger Quantum Correlations by a Bounded Communication Simulation Protocol. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 020401 (2011).

Branciard, C., Cavalcanti, E. G., Walborn, S. P., Scarani, V. & Wiseman, H. M. One-sided device-independent quantum key distribution: Security, feasibility, and the connection with steering. Phys. Rev. A 85, 010301(R) (2012).

Chen, S. L. et al. Quantifying Non-Markovianity with Temporal Steering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 020503 (2016).

Reid, M. D. Demonstration of the Einstein-Podolsky- Rosen paradox using nondegenerate parametric amplification. Phys. Rev. A 40, 913 (1989).

Cavalcanti, E. G., Jones, S. J., Wiseman, H. M. & Reid, M. D. Experimental criteria for steering and the Einstein-Podolsky- Rosen paradox. Phys. Rev. A 80, 032112 (2009).

Schneeloch, J., Broadbent, C. J., Walborn, S. P., Cavalcanti, E. G. & Howell, J. C. Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen steering inequalities from entropic uncertainty relations. Phys. Rev. A 87, 062103 (2013).

Pramanik, T., Kaplan, M. & Majumdar, A. S. Fine-grained Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-steering inequalitie. Phys. Rev. A 90, 050305 (2014).

Schneeloch, J., Dixon, P. B., Howland, G. A., Broadbent, C. J. & Howell, J. C. Violation of continuous-variable Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen steering with discrete measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 130407 (2013).

Kogias, I., Skrzypczyk, P., Cavalcanti, D., Acín, A. & Adesso, G. Hierarchy of Steering Criteria Based on Moments for All Bipartite Quantum Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 210401 (2015).

Saunders, D. J., Jones, S. J., Wiseman, H. M. & Pryde, G. J. Experimental EPR-steering using Bell-local states. Nat. Phys. 6, 845–849 (2010).

Walborn, S. P., Salles, A., Gomes, R. M., Toscano, F. & SoutoRibeiro, P. H. Revealing Hidden Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Nonlocality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 130402 (2011).

Cavalcanti, E. G., Foster, C. J., Fuwa, M. & Wiseman, H. M. Analog of the Clauser-Horne-Shimony-Holt inequality for steering. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 32, A74 (2015).

Ji, S. W., Lee, J., Park, J. & Nha, H. Steeing criteria via covariance matrices of local observables in arvitary-dimensional quantum systems. Phys. Rev. A. 92, 062130 (2015).

Roy, A., Bhattacharya, S. S., Mukherjee, A. & Banik, M. Optimal quantum violation of Clauser-Horne-Shimony-Holt like steering inequality. J. Phys. A 48, 415302 (2015).

Żukowski, M., Dutta, A. & Yin, Z. Geometric Bell-like inequalities for steering. Phys. Rev. A 91, 032107 (2015).

Cavalcanti, D. & Skrzypczyk, P. Quantum steering: a review with focus on semidefinite programming. Prog. Phys. 80, 024001 (2017).

Sun, K. et al. Experimental demonstration of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen steering game based on the all-versus-nothing proof. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 140402 (2014).

Hsieh, C. Y., Liang, Y. C. & Lee, R. K. Quantum steerability: characterization, quantification, superactivation, and unbounded amplification. Phys. Rev. A 94, 062120 (2016).

Skrzypczyk, P., Navascués, M. & Cavalcanti, D. Quantifying Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen steering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 180404 (2014).

Sun, K. et al. Experimental quantification of asymmetric Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen steering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 160404 (2016).

Nguyen, C. & Vu, T. Necessary and sufficient condition for steerability of two-qubit states by the geometry of steering outcomes. Europhys. Lett. 115, 10003 (2016).

Costa, A. C. S. & Angelo, R. M. Quantification of Einstein-Podolski-Rosen steering for two-qubit state. Phys. Rev. A 93, 020103(R) (2016).

Uola, R., Budroni, C., Gühne, O. & Pellonpää, J. P. One-to-One Mapping between Steering and Joint Measurability Problems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 230402 (2015).

Quintino, M. T., Vértesi, T. & Brunner, N. Joint measurability, Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen steering and Bell nonlocality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 160402 (2014).

Uola, R., Moroder, T. & Gühne, O. Joint Measurability of Generalized Measurements Implies Classicality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 160403 (2014).

Cavalcanti, D. & Skrzypczyk, P. Quantitative relations between measurement incompatibility, quantum steering, and nonlocality. Phys. Rev. A 93, 052112 (2016).

Quan, Q. et al. Steering Bell-diagonal states. Sci. Rep. 6, 22025 (2016).

Xiao, Y. et al. Demonstration of multiSetting one-way Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen steering in two-qubit systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 140404 (2017).

Händchen, V. et al. Observation of one-way Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Steering. Nat. Photon 6, 596–599 (2012).

Bowles, J., Vértesi, T., Quintino, M. T. & Brunner, N. One-way Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Steering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 200402 (2014).

Yu, S. X., Liu, N. L., Li, L. & Oh, C. H. Joint measurement of two unsharp observables of a qubit. Phys. Rev. A 81, 062116 (2010).

Stano, P., Peitzner, D. & Heinosaari, T. Coexistence of qubit effects. Quan. Inf. Proc. 9, 143–169 (2010).

Stano, P., Peitzner, D. & Heinosaari, T. Coexistence of qubit effects. Phys. Rev. A 78, 012315 (2008).

Clauser, J. F., Horne, M. A., Shimony, A. & Holt, R. A. Proposed Experiment to Test Local Hidden-Variable Theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 23, 880 (1969).

Horodecki, R., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, M. Violating Bell inequality by mixed spin-12 states: necessary and sufficient condition. Phys. Lett. A 200, 340 (1995).

Wollmann, S., Walk, N., Bennet, A. J., Wiseman, H. M. & Pryde, G. J. Observation of Genuine One-Way Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Steering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 160403 (2016).

Jevtic, S., Pusey, M., Jennings, D. & Rudolph, T. Quantum Steering Ellipsoids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 020402 (2014).

Yu, S. X., Oh, C. H. Quantum contextuality and joint measurement of three observables of a qubit, arXiv: 1312.6470.

Pau, R. & Ghosh, S. Approximate joint measurement of qubit observables through an Arthur-Kelly model. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 44, 485303 (2011).

Kiukas, J., Budroni, C., Uola, R., and Pellonpää, J. P. Uola, R., Lever, F., Gühne, O, and Pellonpää, J. P. Continuous variable steering and incompatibility via state-channel duality, arXiv: 1704.05734.

Uola, R., Lever, F., Gühne, O, and Pellonpää, J. P. Unified picture for spatial, temporal and channel steering, arXiv: 1707.09237.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the NSFC under no. 11571313,11475089, 11675113.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.C. and X.Y. initiated the research, Z.C. proved the main theorems and developed the numerical codes, and Z.C. X.Y. and S.F. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Ye, X. & Fei, SM. Quantum steerability based on joint measurability. Sci Rep 7, 15822 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15910-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15910-8

This article is cited by

-

Detecting EPR steering via two classes of local measurements

Quantum Information Processing (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.