Abstract

Since the 1960s, large-scale deforestation in the Amazon Basin has contributed to rising global CO2 concentrations and to climate change. Recent advances in satellite observations enable estimates of gross losses of above-ground biomass (AGB) stocks due to deforestation. However, because of simultaneous regrowth, the net contribution of deforestation emissions to rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations is poorly quantified. Climate change may also reduce the potential for forest regeneration in previously disturbed regions. Here, we address these points of uncertainty with a machine-learning approach that combines satellite observations of AGB with climate data across the Amazon Basin to reconstruct annual maps of potential AGB during 1993–2012, the above-ground C storage potential of the undisturbed landscape. We derive a 2.2 Pg C loss of AGB over the study period, and, for the regions where these losses occur, we estimate a 0.7 Pg C reduction in potential AGB. Thus, climate change has led to a decline of ~1/3 in the capacity of these disturbed forests to recover and recapture the C lost in disturbances during 1993–2012. Our approach further shows that annual variations in land use change mask the natural relationship between the El Niño/Southern Oscillation and AGB stocks in disturbed regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The terrestrial carbon sink helps offset about 25% of anthropogenic emissions of fossil-fuel responsible for climate change1,2. While tropical forests are a major contributor to this sink, recent large-scale deforestation has weakened the capacity of the Amazonian forest to remain a long-term carbon store. The extent of land cover change in the Amazon Basin can now be quantified with some degrees of confidence using satellite-based observations3. Merging these observations with maps4,5 of Aboveground Biomass Carbon (AGB) provides a baseline estimation of gross losses from deforestation6. However, corresponding emissions may be partially compensated by regrowth in previously cleared areas1 while climate change, and extremes in particular, may alter the capacity of Amazonian forests to sequester C7. Therefore, estimates of the long-term net impact of large-scale deforestation and degradation on the land carbon sink, and its potential for recovery, are challenging to establish.

A way to address these problems is to study the deviation of current AGB stocks from potential stocks, to determine and separate the human-induced and climate-induced biomass deficits. These potential stocks are those that would exist under current climate if previous large-scale deforestation and degradation had not occurred (potential AGB further noted as AGBpot 8; see Methods). AGBpot can also be considered as a measure of local suitability for long-term carbon storage to inform reforestation and afforestation mitigation strategies. While it is not a directly measurable quantity, AGBpot is comparable to carbon stocks predicted by terrestrial ecosystem models that omit land use and land cover change activities8 (such as those participating in the Intersectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project, ISI-MIP9,10,11).

In a previous study8, maps of AGBpot have been reconstructed over the Amazon Basin based on the relationship between climate12 and maps of observed AGB in the tropics4,5 (AGBobs) inside Intact Forest Landscapes13 (IFL). This study estimated a current human-driven AGB deficit (AGBdef = AGBpot − AGBobs) ranging from 7.3 to 8 Pg C, or 11.6–12.2% of the basin-wide AGBpot. However, this previous approach relied on AGBobs derived from data amalgamated over several years, which prevented any analysis of the evolution of AGBdef. Indeed, AGBdef continuously evolves through time as it is the difference between AGBpot, which is only driven by climate and atmospheric CO2 concentrations, and AGBobs which is driven by land use activities as well as climate and atmospheric CO2 concentrations. For example, anthropogenic activities such as deforestation (reforestation) may lead to a decrease (increase) in AGBobs stocks, resulting in positive (negative) trend in AGBdef. Meanwhile, the CO2-fertilization effect may lead to a greater potential for forest regeneration (i.e. greater AGBpot) as recent findings indicate it is the main driver of a global greening of the land surface14. However, locally changing climate conditions may lead to a reduction of the resilience of tropical forests and a transition toward less densely vegetated savannah landscapes15. There is a projected risk of Amazon die-back7 due to climate change, albeit with large uncertainty on its occurrence and severity16. It would reduce the potential for biomass recovery associated with reforestation by the end of the 21st century. Therefore, it is important to estimate the resilience of AGBpot to climate change to design efficient climate mitigation strategies based on reforestation.

In this study, we build on a previous approach8 (see Methods) to address the evolution of AGBpot, and hence AGBdef, using a new dataset17 that provides annual estimates of AGBobs from 1993 to 2012 at a 0.25° spatial resolution. By doing so, we aim to answer the following questions:

-

How did AGBdef evolve in disturbed regions of the Amazon Basin over these two decades?

-

Can we apportion this evolution to climate conditions affecting AGBpot versus human activities reducing AGBobs?

-

Would reforestation-based mitigation strategies be resilient to climate change in previously cleared regions of the Amazon Basin?

Results

We estimate a change in AGBobs from 26.3 Pg C (with a 4.1 Pg C confidence range) in 1993 to 24.1 Pg C (with a 3.9 Pg C confidence range) in 2012, or a 2.2 Pg C (with a 0.2 Pg C confidence range) loss in regions of the Amazon basin which are not IFL. Using the machine-learning approach we derive a reduction of AGBpot from 32.1 Pg C (with a 4.0 Pg C confidence range) in 1993 to 31.4 (with a 3.9 Pg C confidence range) in 2012 in the same regions. Comparing the evolution of AGBobs and AGBpot results in a human-driven increase in AGBdef from 18.0% (AGBdef/AGBpot) in 1993 (with a 2.3% confidence range) to 23.3% in 2012 (with a 2.7% confidence range). Overall, ~1.5 Pg C of the ~7.3 Pg C mean AGBdef in 2012 was generated by combined anthropogenic activities and climate patterns since 1993 (Table 1). The evolution of AGBdef is strongly linear during 1993–2005 (r = 0.99; p ≪ 0.001) before plateauing from 2005 onwards with no significant trend (Fig. 1). The stabilisation of AGBdef after 2005 is associated to a reduction of AGBobs loss rate from 0.17 Pg C y−1 (with a 6% relative uncertainty) to 0.04 Pg C y−1 (with a 14% relative uncertainty) before and after 2005 respectively (Fig. 2). It corresponds to a reduction in deforestation rates over the Brazilian Amazon seen in data from INPE (Figure S1 in the Supplementary Information; r = 0.97; p ≪ 0.001) while the smooth decreases of AGBpot throughout the study period indicates a long-term negative impact of climate on the regeneration potential of disturbed regions (Fig. 2).

Time series of AGBdef in disturbed areas of the Amazon Basin expressed as a fraction of AGBpot. The green area represents the 5th and 95th percentile while the thick black line represents the mean. The shaded time period 1993–2005 highlights when the basin-wide increase in AGBdef exhibits a linear trend (r = 0.99; p ≪ 0.001) before this trend disappears after 2005.

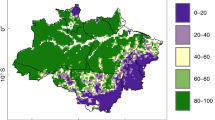

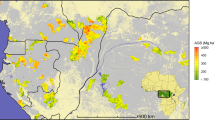

The increase in AGBdef is heterogeneously distributed across disturbed areas of the basin (Fig. 3). While the spatial distributions of AGBdef are significantly correlated (r = 0.89; p ≪ 0.001) in 1993 (Fig. 3a) and 2012 (Fig. 3b), AGBdef increased by more than 50 Mg C ha−1 in some parts of the Brazilian arc of deforestation (between 10°S and 15°S; Fig. 3c) and in central Bolivia (south of 15°S; Fig. 3c). We note a reduction in AGBdef, i.e. a recovery of AGBobs stocks toward AGBpot, in the south-eastern edge of the basin, and to a lesser extent in northern Brazil. This recovery indicates that non-primary vegetation, mostly rangeland in these regions, may have built up biomass stocks from 1993 to 2012. Over the period 1993–2012, local increases in AGBdef can be explained by the erosion of primary land (Fig. 4). Conversely, local recovery of stocks associated to decreases in AGBdef corresponds to regions where the fraction of primary land was already low in 1993. This pattern indicates a recovery of AGB stocks in other land cover types, principally rangelands (Figure S2). Despite this apparent recovery of AGB stocks, the deficits in these regions were still > 50 Mg C ha−1 in 2012.

Aboveground Biomass Carbon deficit (AGBdef) in (a) 1993, (b) 2012 and (c) the change in AGBdef over these two decades (c). Untouched IFL areas are represented in grey. In sub-panel c, positive (red) values indicate an erosion of AGB stocks while negative (green) values indicate a partial recovery. Maps were created using the cartopy module version 0.12.0 (http://scitools.org.uk/cartopy/) for python 2.7 (http://www.python.org/).

(a) Fraction of primary land outside IFL regions in 1993. Grey areas represent IFL regions. (b) Change in fraction of primary land between 1993 and 2012. Blue represents the decline in primary land during 1993–2012. (c) Temporal correlation between fraction of primary land and AGBdef from 1993 through 2012 over each 0.25° grid cell. Hatched areas represent statistically significant correlation (p < 0.05). A negative correlation indicates an increase in AGBdef (i.e. an erosion of AGB stocks) when the fraction of primary land decreases through time. Maps were created using the cartopy module version 0.12.0 (http://scitools.org.uk/cartopy/) for python 2.7 (http://www.python.org/).

Our estimates indicate a significant negative correlation between inter-annual variations of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO), represented by a winter composite of the Multivariate ENSO Index (MEIw, see methods) and detrended ΔAGBpot integrated over previously disturbed regions (Figure S3 in the Supplementary Information; r = −0.57; p ≈ 0.01). This relationship indicates that negative (La Niña) phases of ENSO would drive positive anomalies in ΔAGBpot, i.e. a stronger sink, while positive (El Niño) phases of ENSO are associated with negative anomalies in ΔAGBpot, a weaker sink. However, past and current human activities mean that this significant relationship between ENSO and the sink strength disappears when comparing with de-trended ΔAGBobs (r = −0.38, p > 0.10). We conclude that, through clearing and subsequent regrowth, human activities have become the main driver of inter-annual variability of the land-based sink, dominating natural climate drivers, in disturbed regions of the Amazon.

Discussion

The annual biomass maps have allowed resolution of AGB changes across the Amazon Basin, indicating areas of heavy losses, but also some areas of AGB gain (Fig. 3). By mapping the potential biomass, we show the evolution of the basin’s capacity to store C, a baseline without human impacts. Because AGBpot is determined from annual AGBobs data in IFL, the annual variation in AGBpot indicates the effect of climate on the storage capacity of the intact forest. We show that this potential has declined over 1993–2012 (Fig. 2) similarly to AGB stocks in IFL (Figure S4 in the Supplementary Information), due to climate and in spite of rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations (Table 1). Indeed, the evolution of AGB stocks in IFL is significantly correlated with the vegetation water stress estimated by GLEAM18 (r = 0.64; p < 0.01). The post-2005 decrease in AGB stocks in IFL follows a transition to stronger stress conditions around 2002 that prevail until the end of the study period in 2012. This transition toward more water-stressed conditions corresponds to the onset of the 2002–2003 El Niño episode19 followed by the 2005 and the 2010 Amazonian droughts20,21. Overall, these results indicate that drying conditions have degraded the capacity of the disturbed regions to regain their lost biomass which is line with the projected risk of climate driven Amazon biomass loss7. This climate-driven reduction in the capacity for regeneration also corroborates with risks for tropical forests to be replaced by savannahs if drier conditions dominates15.

Our results are first-order estimates and we are aware that hard-to-quantify and potentially large uncertainties may arise from ground-level measurements22, the way they are used in combination with remote-sensing data to derive large-scale biomass maps23, and the identification of forest cover24 and intact forest landscapes13. Therefore, we have validated the robustness of our machine-learning approach in several ways. First, it simulates annual AGBobs with <0.1% bias integrated over out-of-sample IFL regions (Figure S5a in the Supplementary Information). We note a tendency to overestimate AGB in less densely vegetated regions (Figure S5b,c in the Supplementary Information) but the local mean relative bias is <1.2%. Second, pixel to country-scale estimates of the evolution of AGBdef through time are in agreement with independent datasets of deforestation (Figure S1) and land cover change rates (Fig. 3). Finally, the ~7.3 Pg C AGBdef estimated after 2005 is similar to the one reported previously8. Our highest confidence results indicate a ~0.08 Pg C y−1 increase in AGBdef for the period 1993–2012. This net number is about half of recent estimates of gross C emissions from the Amazonian deforestation25. It is in agreement with the ~50% compensation of gross C emissions from tropical deforestation by regrowth1. Assuming that large-scale deforestation started in 1960 (ref.26), the initial AGBdef of ~5.8 Pg C in 1993 corresponds to a higher 0.18 Pg C y−1 net biomass loss prior to this date. The decrease in AGBdef growth rate between 1993 and 2012, and especially after 2005 (Fig. 1), matches reports of a slowing down of Brazilian deforestation during 2005–2012 (refs26,27,28) but is also a result of a decrease in AGBpot in disturbed regions of the Amazon Basin.

Furthermore, field studies20,21 and airborne measurements29 have shown that climate variability, and especially El Niño-induced droughts, have a large impact on the carbon balance of undisturbed areas of the Amazon Basin. These previous results are in agreement with the negative correlation between MEIw and ΔAGBpot (Figure S3 in the Supplementary Information). Overall, human-induced clearing and recovery processes mask the natural response of ecosystems to climate in disturbed parts of the Amazon Basin. While this impact is intuitive, we are able to demonstrate it quantitatively with the AGBpot reconstructions. Finally, this result raises concerns on the viability of climate change mitigation strategies, as climate change is likely to challenge the resilience of forested landscapes.

Conclusion

We have recreated annual maps of potential AGB for the Amazon Basin, which allows the net impacts of global change on basin biomass to be determined. Compared to maps of historical biomass, these indicate an increase of ~1.5 Pg C in the biomass deficit (AGBdef) for 1993–2012. This basin-wide number is a net estimate of climate-induced variation of AGBpot and deforestation-induced erosion of AGB stocks, which are partly compensated by regrowth in some areas post-deforestation. Overall, our results indicate that land use change continues to erode the carbon storage of the Amazon basin while climate change is impairing its capacity to sequester carbon through natural processes of regrowth, raising concerns on the long-term resilience of land-based mitigation strategies.

Methods

Annual maps of AGB

We use annual Above Ground Biomass maps17 (AGBobs) for the period 1993 through 2012 based on the passive microwave observed vegetation optical depth (VOD, dimensionless) from a series of satellites. VOD is an indicator of the total water content in the aboveground vegetation, i.e. including both canopy and woody components30,31,32. This VOD dataset can qualitatively capture the long-term and inter-annual variations in vegetation water content over different land cover types33,34,35,36,37. Annual AGBobs maps were created by establishing a relationship between VOD and a pan-tropical map4 of AGBobs circa 2000. These annually resolved maps are comparable with previous independent estimates of AGB dynamics1,5,6. For more details about the methodology used to create AGBobs maps, please refer to Liu et al. (2015, ref.17).

Creating potential AGB maps

To derive the evolution of the AGB deficit (AGBdef) we first created annually resolved maps of potential Above Ground Biomass (AGBpot) in previously disturbed regions. AGBpot corresponds to AGB stocks there would exist under current climate if deforestation had not occurred in these regions. It can also be conceptualized as the current forest regeneration potential if regrowth was instantaneous. The method to create AGBpot maps was described in Exbrayat and Williams (2015; ref.8) and is only briefly summarized hereafter.

First, we used a Random Forest machine-learning algorithm38,39 to reproduce AGBobs as a function of climatology in identified Intact Forest Landscapes (IFL) which cover about 55% of the Amazon Basin. The Random Forest technique relies on multiple decision trees (here n = 1,000) to group data points as a function of driving data. Then, in each final node a multiple linear regression is trained to predict the target variable (here AGBobs) as a function of explanatory data. Each individual decision tree is trained on a randomly selected subset of the data and the final prediction is the average of all trees. Here, we use the CRU CL2.0 climatology dataset12, re-gridded to a matching 0.25° resolution with the Climate Data Operators version 1.6.9, and latitude, a proxy of intra-annual photoperiod amplitude, as explanatory variables to predict AGB in IFL. The assumption is made that regions identified as ‘intact’ may be subject to small-scale indigenous management40 or disturbances41 that are negligible at the coarser 0.25° resolution used here8. Compared to our previous study we used an updated IFL dataset13 that represents the extent of intact regions for the year 2013. It ensures that training regions have remained intact throughout the whole period covered by the AGBobs dataset (i.e. 1993–2012). In addition to these continuous drivers, we used a categorical variable to separate pixels corresponding to large-scale open water regions in the Global Lakes and Wetlands Database42. As VOD values are strongly influenced by the open water dynamics, the pixels with large-scale open water are identified and the VOD values over these pixels are assumed constant among different years17.

Once trained the algorithm can then be used to estimate annual, climate-driven, AGBpot in previously disturbed regions (i.e. outside IFL) regions. Although it has been identified as the major driver of the recent greening of the land surface14, CO2 is not explicitly used in our approach because of the lack of availability of spatially-explicit data of atmospheric concentrations. However, we assume that the impact of increasing CO2 on AGB stocks is intrinsically included in time series of AGB in IFL which also include the impact of changing climatic conditions. Using annual maps of AGBpot we can calculate an AGB deficit (AGBdef = AGBpot − AGBobs) and derive time series of its evolution from 1993 to 2012. As the temporal evolution of AGBpot is only driven by climate and atmospheric CO2 concentrations, we assume that AGBdef is representative of the net and cumulative impact of anthropogenic activities on biomass dynamics on AGB stocks. We perform the analyses using the mean AGBobs from Liu et al. (ref.17) to derive AGBpot and AGBdef. Furthermore, we evaluate the uncertainty in our approach by performing the analysis with the 5th and 95th percentiles of AGBobs data17 to report the corresponding confidence ranges in AGBpot and AGBdef. As a proof of concept, we first validate the method using ~50% of randomly selected pixels in IFL as training dataset and the remaining IFL pixels as target dataset to assess the robustness of the approach to recreate 20 years of AGBpot. Corresponding results are presented in Figure S5 of the supplement. We note a good agreement between reconstructions and data in IFL although there is a tendency for the machine-learning to overestimate AGB in less densely vegetated regions.

Validation of results

Our estimates of AGBpot cannot be directly validated against field data. However, we expect the temporal evolution of AGBdef to be related to contemporary deforestation rates and land cover changes. Therefore, we compare time series of AGBpot from pixel to country-scale with independent datasets of Land Use and Land Cover Change (LULCC). First, we compare annual deforestation rates reported by INPE for the Brazilian part of the Amazon Basin with the corresponding trend in AGBdef over the whole period 1993–2012. Second, we use spatially-explicit data from the Land-Use Harmonization project version 2 (LUH2v2h; data updated from ref.43). LUH2v2h is a global driving dataset that provides annual land cover information for the period 850–2015 C.E. in the Land Use Model Intercomparison Project44 (LUMIP) contribution to the upcoming sixth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project45 (CMIP6). In LUH2v2h land covers are distributed between 12 classes (2 primary land classes, 2 secondary land classes, 5 cropland classes, 2 pasture and rangeland classes and 1 urban class) and the fraction they cover in each 0.25° pixel is reported annually.

Climate sensitivity

We compare the evolution of AGBobs in IFL with time series of the vegetation stress factor S from the GLEAM dataset v 3.1a (ref.18). GLEAM is a data-assimilation system that uses satellite observations to constrain daily estimates of global terrestrial evaporation and root-zone soil moisture46. The factor S is an output of GLEAM and represents the ratio of actual evapotranspiration to potential evapotranspiration, an indicator of ecosystem’s water stress. It is as a function of vegetation state and soil moisture availability and therefore takes long-term effects of precipitation conditions into account. We use the mean annual value of S across the IFL regions of the Amazon Basin, expressed as a z-score, to explain the evolution of AGBobs (Figure S4).

We seek to further understand the impact of large-scale human disturbances by quantifying their impact on the response of ecosystems to climate variability. We focus on the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a main driver of global climate variability47. The state of ENSO, quantified through the calculations of an index, significantly correlates with the strength of the global land carbon sink48. Indeed, positive (negative) El Niño (La Niña) phases drive warmer and drier (cooler and wetter) conditions over large parts of the pan-tropical region, including the Amazon Basin, which explains spatial patterns of ecosystem carbon uptake48. Following previous studies48,49 we use a winter composite of the Multivariate ENSO Index50,51 calculated between Dec/Jan and Mar/Apr (referred as MEIw). To quantify the impact of human disturbances on the response of the Amazon terrestrial carbon sink to ENSO, we study the correlation between MEIw and detrended anomalies of annual ΔAGBobs and ΔAGBpot stocks integrated over disturbed (i.e. non-IFL) regions of the Amazon Basin. We choose to rely on a global index rather than actual data of temperature and precipitation for the Amazon Basin because past deforestation may have altered these quantities in regions where land-atmosphere coupling is strong52,53.

Data availability

The data generated during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Pan, Y. et al. A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science 333, 988–993 (2011).

Le Quéré, C. et al. Global Carbon Budget 2015. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 7, 349–396 (2015).

Hansen, M. C. et al. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 342, 850–853 (2013).

Saatchi, S. S. et al. Benchmark map of forest carbon stocks in tropical regions across three continents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 9899–9904 (2011).

Baccini, A. et al. Estimated carbon dioxide emissions from tropical deforestation improved by carbon-density maps. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 182–185 (2012).

Harris, N. L. et al. Baseline map of carbon emissions from deforestation in tropical regions. Science 336, 1573–1576 (2012).

Cox, P. M. et al. Sensitivity of tropical carbon to climate change constrained by carbon dioxide variability. Nature 494, 341–344 (2013).

Exbrayat, J.-F. & Williams, M. Quantifying the net contribution of the historical Amazonian deforestation to climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 2968–2976 (2015).

Friend, A. D. et al. Carbon residence time dominates uncertainty in terrestrial vegetation responses to future climate and atmospheric CO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3280–3285 (2014).

Nishina, K. et al. Quantifying uncertainties in soil carbon responses to changes in global mean temperature and precipitation. Earth Syst. Dyn. 5, 197–209 (2014).

Warszawski, L. et al. The Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISI-MIP): project framework. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3228–32 (2014).

New, M., Lister, D., Hulme, M. & Makin, I. A high-resolution data set of surface climate over global land areas. Clim. Res. 21, 1–25 (2002).

Potapov, P. et al. Mapping the world’s intact forest landscapes by remote sensing. Ecol. Soc. 13, 51 (2008). doi:Artn.

Zhu, Z. et al. Greening of the Earth and its drivers. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 791–795 (2016).

Hirota, M., Holmgren, M., Van Nes, E. H. & Scheffer, M. Global resilience of tropical forest and savanna to critical transitions. Science 334, 232–235 (2011).

Rammig, A. et al. Estimating the risk of Amazonian forest dieback. New Phytol. 187, 694–706 (2010).

Liu, Y. Y. et al. Recent reversal in loss of global terrestrial biomass. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 470–474 (2015).

Martens et al. GLEAMv3: satellite-based land evaporation and root-zone soil moisture. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 1903–1925 (2017).

Zeng et al. Causes and impacts of the 2005 Amazon drought. Env. Res. Lett. 3, 014002 (2008).

Phillips, O. L. et al. Drought sensitivity of the Amazon rainforest. Science 323, 1344–1347 (2009).

Lewis, S. L. et al. The 2010 Amazon drought. Science 331, 554 (2011).

Chave, J. et al. Improved allometric models to estimate the aboveground biomass of tropical trees. Glob. Chang. Biol. 20, 3177–3190 (2014).

Réjou-Méchain, M. et al. Local spatial structure of forest biomass and its consequences for remote sensing of carbon stocks. Biogeosciences 11, 5711–5742 (2014).

Sexton, J. O. et al. Conservation policy and the measurement of forests. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 192–196 (2015).

Loarie, S. R., Asner, G. P. & Field, C. B. Boosted carbon emissions from Amazon deforestation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L14810 (2009).

Ramankutty, N. et al. Challenges to estimating carbon emissions from tropical deforestation. Global Change Biol. 13, 51–66 (2007).

Nepstad, D. et al. Inhibition of Amazon deforestation and fire by parks and indigenous lands. Conservat. Biol. 20, 65–73 (2006).

Malhi, Y. et al. Climate change, deforestation, and the fate of the Amazon. Science 319, 169–72 (2008).

Gatti, L. V. et al. Drought sensitivity of Amazonian carbon balance revealed by atmospheric measurements. Nature 506, 76–80 (2014).

Jackson, T. J. & Schmugge, T. J. Vegetation effects on the microwave emission of soils. Remote Sens. Environ. 36, 203–212 (1991).

Kerr, Y. H. & Njoku, E. G. A semiempirical model for interpreting microwave emission from semiarid land surfaces as seen from space. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 28, 384–393 (1990).

Guglielmetti, M. et al. Measured microwave radiative transfer properties of a deciduous forest canopy. Remote Sens. Environ. 109, 523–532 (2007).

Liu, Y. Y., de Jeu, R. A. M., McCabe, M. F., Evans, J. P. & van Dijk, A. I. J. M. Global long-termpassive microwave satellite-based retrievals of vegetation optical depth. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L18402 (2011).

Liu, Y. Y., van Dijk, A. I. J. M., McCabe, M. F., Evans, J. P. & de Jeu, R. A. M. Global vegetation biomass change (1988–2008) and attribution to environmental and human drivers. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 22, 692–705 (2013).

Andela, N., Liu, Y. Y., van Dijk, A. I. J. M., de Jeu, R. A. M. & McVicar, T. R. Global changes in dryland vegetation dynamics (1988–2008) assessed by satellite remote sensing: comparing a new passive microwave vegetation density record with reflective greenness data. Biogeosciences 10, 6657–6676 (2013).

Tian, F. et al. Remote sensing of vegetation dynamics in drylands: Evaluating vegetation optical depth (VOD) using AVHRR NDVI and in situ green biomass data over West African Sahel. Remote Sens. Environ. 177, 265–276 (2016).

Tian, F., Brandt, M., Liu, Y. Y., Rasmussen, K. & Fensholt, R. Mapping gains and losses in woody vegetation across global tropical drylands. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 1748–1760 (2017).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Ramankutty, N. & Foley, J. A. Estimating historical changes in global land cover: Croplands from 1700 to 1992. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 13, 997–1027 (1999).

Espírito-Santo, F. D. B. B. et al. Size and frequency of natural forest disturbances and the Amazon forest carbon balance. Nat. Commun. 5, 3434 (2014).

Lehner, B. & Doll, P. Development and Validation of a Global Database of Lakes, Reservoirs and Wetlands. J. Hydrol. 296, 1–22 (2004).

Hurtt, G. C. et al. Harmonization of land-use scenarios for the period 1500–2100: 600 years of global gridded annual land-use transitions, wood harvest, and resulting secondary lands. Climatic Change 109, 117–161 (2011).

Lawrence, D. M. et al. The Land Use Model Intercomparison Project (LUMIP) contribution to CMIP6: rationale and experimental design. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 2973–2998 (2016).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Miralles, D. G. et al. Global land-surface evaporation estimated from satellite-based observations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 15, 453–469 (2011).

Trenberth, K. The Definition of El Niño. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 78, 2771–2777 (1997).

Bastos, A., Running, S. W., Gouveia, C. & Trigo, R. M. The global NPP dependence on ENSO: La Niña and the extraordinary year of 2011. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 118, 1247–1255 (2013).

Vicente‐Serrano, S. M. et al. A multiscalar global evaluation of the impact of ENSO on droughts. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 116, D20109 (2011).

Wolter, K. & Timlin, M. S. Measuring the strength of ENSO events - how does 1997/98 rank? Weather 53, 315–324 (1998).

Wolter, K. & Timlin, M. S. El Niño/Southern Oscillation behaviour since 1871 as diagnosed in an extended multivariate ENSO index (MEI.ext). Intl. J. Climatology 31, 1074–1087 (2011).

Koster, R. D. et al. Regions of strong coupling between soil moisture and precipitation. Science 305, 1138–1140 (2004).

Lorenz, R. & Pitman, A. J. Effect of land-atmosphere coupling strength on impacts from Amazonian deforestation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 5987–5995 (2014).

Acknowledgements

J.-F.E. and M.W. are supported by the Natural Environment Research Council through the National Centre for Earth Observation. Y.Y.L. is supported by the Nanjing University Information Science and Technology (NUIST) Start-up Research Grant and also a recipient of Thousand Talents Plan for Young Outstanding Scientists in China. The authors are grateful to the community for the availability of data and software which made this study possible:

- Climate Data Operators are available from http://www.mpimet.mpg.de/cdo.

- IFL geographical data was downloaded from http://www.intactforests.org.

- INPE annual estimates of Brazilian deforestation are available online at http://www.obt.inpe.br/prodes/prodes_1988_2012.htm.

- LUH2 v2h data is available from http://luh.umd.edu.

- Monthly MEI time series were downloaded from http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/enso/mei/.

- GLEAM version 3.1a is available from http://www.gleam.eu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed the study, Y.Y.L. provided annual AGB maps, J.-F.E. performed the analyses and wrote the paper with contribution from both co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Exbrayat, JF., Liu, Y.Y. & Williams, M. Impact of deforestation and climate on the Amazon Basin’s above-ground biomass during 1993–2012. Sci Rep 7, 15615 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15788-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15788-6

This article is cited by

-

Does climate change alter the nutrient trends of Cedrela fissilis Vell. trees in the southern Brazilian Amazon?

Ecological Processes (2023)

-

Understanding the Land Carbon Cycle with Space Data: Current Status and Prospects

Surveys in Geophysics (2019)

-

Aspects of Forest Biomass in the Earth System: Its Role and Major Unknowns

Surveys in Geophysics (2019)

-

Machine learning classification for field distributions of photonic modes

Communications Physics (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.