Abstract

A key question in our understanding of itch coding mechanisms is whether itch is relayed by dedicated molecular and neuronal pathways. Previous studies suggested that gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) is an itch-specific neurotransmitter. Neuromedin B (NMB) is a mammalian member of the bombesin family of peptides closely related to GRP, but its role in itch is unclear. Here, we show that itch deficits in mice lacking NMB or GRP are non-redundant and Nmb/Grp double KO (DKO) mice displayed additive deficits. Furthermore, both Nmb/Grp and Nmbr/Grpr DKO mice responded normally to a wide array of noxious stimuli. Ablation of NMBR neurons partially attenuated peripherally induced itch without compromising nociceptive processing. Importantly, electrophysiological studies suggested that GRPR neurons receive glutamatergic input from NMBR neurons. Thus, we propose that NMB and GRP may transmit discrete itch information and NMBR neurons are an integral part of neural circuits for itch in the spinal cord.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The spinal cord dorsal horn is comprised of multiple micro neural circuits, which may function through cascades, in parallel, or in an overlapping manner. Itch and pain are transmitted from the periphery by the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons to the spinal cord. Projection neurons of lamina I and V send the signals to the supraspinal sensory nuclei, and evidence indicates that itch and pain signals are processed by modality specific interneurons to shape projection output of the spinal cord. Understanding how itch and pain information is encoded and transmitted by a myriad of neuropeptides as well as by discrete neural circuits, however, poses a significant challenge1,2,3,4,5. Central to the challenge is the question of whether there are itch-specific neurotransmitters and neural circuits (pruriceptors), and if so, how they transmit different types of itch information from primary pruriceptor afferents to the brain. Among numerous neuropeptides identified in DRGs, GRP has emerged as a putative itch-specific neuropeptide3,6,7,8,9. The role of GRP-GRPR signaling is largely restricted to nonhistaminergic itch6,10,11, including opioid-induced itch8. Although GRPR may compensate for histaminergic itch, this mechanism can be explained by a cross-signaling model rather than the actual requirement for GRPR in histamine-induced itch12. At the circuit level, spinal neuronal ablation and behavioral studies suggested that spinal GRPR neurons constitute a central itch-specific circuit7,13,14,15,16. Rendering further support for the role of GRP-GRPR signaling in itch, we recently reported that GRP/GRPR in suprachiasmatic nucleus is also required for contagious itch behavior17.

Neuromedin B (NMB), another member of the mammalian bombesin peptide family, is more broadly expressed than GRP in DRGs, predominantly in Isolectin B4 Griffonia simplicifolia- (IB4)-binding neurons12,18,19, which was thought to be non-peptidergic neurons20. NMBR interneurons are mostly glutamatergic and intermixed with GRPR neurons in laminae I-II of the spinal cord12. Past studies have shown that intrathecal (i.t.) injection of NMB elicits dose-related scratching behavior with a rapid onset profile, indicating a direct activation of NMBR by NMB in the spinal cord12,21,22,23. GRP can bind to NMBR or NMB to GRPR with lower affinity than their respective cognate receptors24. Behavioral studies suggested that NMB acts exclusively through NMBR to relay itch information, whereas GRP can cross-activate NMBR as well in the spinal cord12. However, NMB-NMBR signaling has also been implicated in pain transmission25, raising an important question as to how NMB may exert its effects on both itch and pain transmission. Lack of a role of GRP in nociceptive processing has been suggested by normal pain behaviors of mice lacking Grp 6. The possibility that NMB may compensate for the loss of GRP in nociceptive processing, however, has yet to be examined.

To address the issue, we generated and analyzed the phenotype of Nmb KO mice, Nmb/Grp double knockout (DKO) mice and Nmbr/Grpr DKO mice. We also studied the role of NMBR neurons in itch and pain and their relation with GRPR neurons using behavioral and electrophysiological approaches. Our studies suggest that spinal NMB-NMBR and GRP-GRPR pathways encode discrete itch information. Moreover, our data suggest that NMBR neurons may function upstream of GRPR neurons via glutamatergic transmission.

Results

Distinct requirement for NMB and GRP in itch transmission

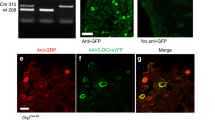

We generated Nmb KO mice using a gene targeting strategy (Fig. 1A) and confirmed the absence of Nmb in Nmb KO mice by PCR (Fig. 1B) and in situ hybridization (ISH) (Fig. 1C). Although eGFP was fused in frame to the first coding exon of Nmb, eGFP fluorescence was not detectable in Nmb heterozygous nor KO mice. This could be attributed to disruption of cis-regulatory elements in the Nmb gene required for appropriate expression of eGFP. To assess the role of NMB in itch transmission, we examined the scratching behavior of Nmb KO mice after intradermal (i.d.) injection of several pruritogens. Surprisingly, compared with WT littermates, Nmb KO mice exhibited a significant attenuation in scratching responses to histamine, compound 48/80 (48/80), and 5-HT (Fig. 1D). These results are in contrast to the normal scratching behavior of Nmbr KO mice in response to the same pruritogens (Fig. S1)12. Notably, Nmb KO mice responded normally to three nonhistaminergic pruritogens: chloroquine (CQ), SLIGRL and BAM8-2226 (Fig. 1D). Mismatched phenotypes of mice lacking Nmb vs. Nmbr prompted us to examine the scratching behavior of Grp KO mice. Interestingly, Grp KO mice displayed significant deficits in the scratching responses to CQ, SLIGRL and BAM8-22, but not to histamine, 48/80 and 5-HT (Fig. 1E). Thus, in a marked contrast to Nmb and Nmbr KO mice, the phenotype of Grp KO mice is reminiscent of that of Grpr KO mice with predominant deficits in nonhistaminergic itch transmission6,7.

NMB and GRP are required for acute itch in a non-overlapping manner. (A) Schematic of gene targeting strategy of Nmb. Exon 1 of the Nmb coding region was replaced with an eGFP-IRES-rtTA-ACN targeting construct to produce a null allele. A diphtheria toxin (DTA) cassette was inserted as a negative selection marker. (B) Representative gel image for genotyping PCR to confirm the targeting of Nmb in mice. 470 bp WT and 370 bp null bands were produced, respectively. (C) In situ hybridization showed signals of Nmb transcripts in WT DRG neurons that were absent in DRGs of Nmb KO mouse. Scale bar, 100 µm. (D) Nmb KO mice showed deficits in scratching response to histamine (200 µg, i.d.) (P = 0.0298), 48/80 (100 µg, i.d.) (P = 0.0378), and 5-HT (50 nmol, i.d.) (P = 0.0239), but not to CQ (200 µg, i.d.) (P = 0.1088), SLIGRL (100 µg, i.d.) (P = 0.7919) or BAM8-22 (100 µg, i.d.) (P = 0.7151). n = 6–12 per genotype. (E) Grp KO mice showed significantly attenuated scratching response to CQ (P = 0.0495), SLIGRL (P = 0.0329), and BAM8-22 (P = 0.0100), but not to histamine (P = 0.1571), 48/80 (P = 0.5582), or 5-HT (P = 0.4616). n = 6 per genotype. (F) Nmb/Grp DKO mice showed deficit in scratching response to histamine (P = 0.0256), 48/80 (P = 0.0373), 5-HT (P = 0.0002), CQ (P = 0.0300), SLIGRL (P = 0.0421), and BAM8-22 (P = 0.0253). n = 6–9 per genotype. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, versus WT, unpaired t test.

To address whether there is a functional redundancy between NMB and GRP, we next assessed the scratching phenotype of Nmb/Grp DKO mice. Nmb/Grp DKO mice showed significantly reduced scratching behaviors in response to all pruritogens tested (Fig. 1F). In contrast to Nmbr/Grpr DKO mice12, Nmb/Grp DKO mice overall did not display further reduction of scratching behaviors in response to acute pruritogens tested relative to Grp or Nmb KO mice, with the exception of 5-HT (Fig. 1F). These suggest that the roles of NMB and GRP in itch transmission are largely non-overlapping.

Normal projection of primary afferents in Nmb/Grp DKO mice

Neuropeptides may be required for neurotrophic function, axonal growth and trafficking of the receptors/peptides27. For example, mice lacking Substance P (SP) exhibited deficits in the expression of several molecules in the dorsal horn28. To determine whether NMB or GRP is required for axonal growth and projection of primary afferents in the spinal cord, we examined several molecular markers using immunohistochemistry (IHC). Innervation patterns of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) positive and IB4-binding primary afferents in the superficial dorsal horn of Nmb/Grp DKO and WT littermate mice appear comparable (Fig. S2A), so are the patterns of SP and TRPV1 primary afferents (Fig. S2B and C). Quantitative analysis confirmed similar intensities of primary afferents for CGRP, IB4 binding, SP and TRPV1 between WT and Nmb/Grp DKO mice (Fig. S2D).

NMB-NMBR and GRP-GRPR are dispensable for pain behaviors

To determine the function of NMB in nociceptive processing, we investigated a myriad of acute and inflammatory pain responses of Nmb KO mice. Nmb KO mice showed normal innocuous and noxious mechanical sensitivity as measured by graded von Frey filaments and Randall-Selitto test, respectively (Fig. 2A and B). Moreover, Nmb KO mice did not show deficits in thermal pain sensitivity, as measured by Hargreave paw withdrawal test (Fig. 2C), hotplate test (Fig. 2D) or tail-immersion test (Fig. 2E). Durations for licking/flinching behaviors of the inflamed paws in response to i.pl. injection of formalin (Fig. 2F), capsaicin (Fig. 3G) and mustard oil (Fig. 2H) were indistinguishable between Nmb KO mice and WT mice. Next we evaluated whether NMB is required for persistent pain behaviors by comparing i.pl. injection of Complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA)-induced inflammatory pain responses between Nmb KO and WT mice. Both groups of mice developed a similar extent of mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity after CFA injection (Fig. 2I and J). We also compared neuropathic pain behaviors of Nmb KO and WT mice using a spared nerve injury (SNI) model29. Nmb KO and WT mice developed mechanical hypersensitivity to a similar extent, indicating normal neuropathic pain in mice lacking NMB (Fig. 2K). Nmb KO mice also showed normal thermal pain sensitivity (Fig. 2L).

Normal pain behaviors of Nmb KO mice. (A and B) Mechanical pain threshold was comparable between Nmb KO mice and their WT littermates as tested by non-noxious von Frey assay (P = 0.1540, n = 6 per genotype) (A) and noxious Randall Selitto assay (P = 0.4072, n = 6–12 per genotype) (B). (C–E) Nmb KO mice showed normal response to thermal stimuli in Hargreaves (P = 0.4908, n = 6–12 per genotype) (C), hotplate (P = 0.5979, n = 6–9 per genotype) (D) and tail immersion (P = 0.9450, n = 6–9 per genotype) (E) tests compared with WT littermates. (F–H) Licking/flinching responses induced by 2% formalin (P = 0.1217, n = 7–10 per genotype) (F) capsaicin (2 µg, i.pl.) (P = 0.7281, n = 7–10 per genotype) (G) and mustard oil (P = 0.1108, n = 6–9 per genotype) (H) were not different between Nmb KO mice and WT littermates. (I and J) CFA induced comparable hypersensitivity to mechanical (I) and thermal stimuli (J) in both WT and Nmb KO mice. n = 6 per genotype. (K) After SNI Nmb KO mice and WT littermates developed similar extent of mechanical hypersensitivity. n = 6 per genotype. (L) SNI did not cause significant effect on thermal sensitivity of WT and Nmb KO mice. n = 6 per genotype. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. Unpaired t-test in (A–C, G and H), repeated measures ANOVA in (D–F and I–L).

Evoked nocifensive behavior and thermal hypersensitivity after i.pl. injection of pruritogens or algogens. (A) Licking/flinching responses induced by NMB (45 μg, i.pl.) in WT and Nmbr KO mice were attenuated by pre-injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) for 30 min. P = 0.0070, WT saline + NMB versus morphine + NMB, P = 0.0413, Nmbr KO saline + NMB versus morphine + NMB. n = 8–9 per genotype. (B and C) WT and Nmbr KO mice developed thermal hypersensitivity (P = 0.0011, WT saline + NMB versus baseline, P = 0.0081, Nmbr KO saline + NMB versus baseline)(B) and mechanical hypersensitivity (P <0.0001, WT saline + NMB versus baseline, P = 0.0323, Nmbr KO saline + NMB versus baseline) (C) upon i.pl. injection of NMB, which was reversed by morphine. n = 8 per genotype. (D) C57BL/B6 mice displayed licking and flinching behavior after i.pl. injection of capsaicin (2 μg), CQ (200 μg) and histamine (200 μg). Pre-injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) for 30 min attenuated licking and flinching behavior evoked by capsaicin (P = 0.0049) and histamine (P = 0.0108), but not by CQ (P = 0.7632). n = 7 per group. (E) Thermal hypersensitivity induced by i.pl. injection of capsaicin (2 μg), CQ (200 μg) and histamine (200 μg) were reversed by pre-injection of morphine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) for 30 min. n = 6–7 per group. (F) i.pl. injection of capsaicin (2 μg), CQ (200 μg) and histamine (200 μg) evoked mechanical hypersensitivity that was reversed by morphine. n = 6 per group. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, versus saline or baseline, unpaired t test.

Likewise, we found that Grp KO mice exhibited normal responses to an array of painful stimuli, including acute mechanical, thermal and noxious chemical stimuli (Fig. S3 A–J). To exclude the developmental and/or functional compensation from GRP in Nmb KO mice, we examined pain behaviors of Nmb/Grp DKO mice. Nmb/Grp DKO mice showed normal responses to acute mechanical and thermal stimuli as well as various algogens (Fig. S4A–H). To determine whether NMB and GRP are involved in mediating more long-lasting inflammatory pain, we studied the inflammatory pain responses of mice that received i.pl. injection of CFA. Nmb/Grp DKO and WT mice showed comparable thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity induced by CFA, suggesting that they are not involved in persistent inflammatory pain (Fig. S4I and J).

To evaluate whether a potential functional /signaling compensation may occur between GRPR and NMBR in nociceptive processing, as shown by normal histamine itch in Nmbr KO mice12, we examined pain behaviors of Nmbr/Grpr DKO Mice. Consistent with the results obtained in Nmb/Grp DKO mice, Nmbr/Grpr DKO mice also displayed normal innocuous and noxious mechanical pain sensitivity (Fig. S5A and B), acute thermal pain sensitivity and inflammatory nocifensive response (Fig. S5C–H). Thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity induced by i.pl. CFA was also comparable between Nmbr/Grpr DKO mice and WT littermates (Fig. S5I and J).

Intraplantar injection of NMB-induced inflammation is not mediated by NMBR

On the basis of the observation that i.pl. injection of NMB caused neurogenic inflammation such as local swelling and thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity, NMB was proposed to be a novel nociceptive signaling molecule25. However, the specificity of exogenous NMB-induced inflammatory response was not tested. To evaluate whether NMB-induced nocifensive behaviors are specific to NMBR, we repeated i.pl. injection of NMB (45 µg) in mice. Both Nmbr KO and WT mice displayed licking/flinching behaviors followed by development of hypersensitivity to thermal and mechanical stimuli (Fig. 3A–C). These responses represent noxious behaviors because they were markedly attenuated by intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) of morphine (10 mg/kg, i.p.), which would reduce pain but not itch-related scratching response30 (Fig. 3A–C). It seems that i.pl. injection of relatively large amount of neuropeptides could invariably result in non-specific nocifensive responses. We thus conclude that observed nocifensive responses induced by i.pl NMB is not mediated by NMBR in sensory neurons.

It has been shown that injections into mouse cheek is an excellent way for distinguishing pain vs. itch by counting forelimb wiping and hind limb scratching, respectively31. In contrast, it was unclear whether behavioral responses evoked by i.pl. injection of neuropeptides reflect exclusively pain, or itch or both. To test this, we examined licking/flinching behaviors after i.pl. injection of algogens and pruritogens, including capsaicin, CQ and histamine and found that all chemicals invariably induced spontaneous licking/flinching behaviors (Fig. 3D). To distinguish painful response from putative pruriceptive response, we treated mice with systemic morphine. Pre-injection of morphine significantly reduced the duration of licking/flinching behaviors evoked by capsaicin and histamine, suggesting that the responses evoked by i.pl. injection of capsaicin and histamine in part reflect a nocifensive component (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, morphine failed to attenuate licking/flinching response evoked by CQ (Fig. 3D), implying that CQ-evoked response is reflective of itch sensation. Although it is difficult to separate biting from licking behaviors unequivocally, the finding that biting was not attenuated by morphine supports the contention that this behavior induced by CQ is an indication of itch rather than pain32. We also examined thermal and mechanical responses evoked by i.pl. injection of capsaicin, CQ and histamine. All three reagents induced thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity that was reversed by i.p. morphine (Fig. 3E and F). These results show that i.pl. injection of “classic” pruritogens activate nociceptive processing. Taken together, these data suggest that behavioral responses elicited by i.pl. injection of exogenous irritants/peptides could reflect either itch or pain or both and the effect could also be non-specific.

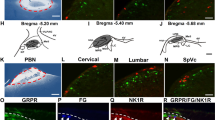

Spinal NMBR+ neurons are important for itch but not pain behaviors

To examine the role of NMBR+ dorsal horn neurons in itch and pain transmission, we treated mice with i.t. NMB-saporin (NMB-sap, 2–3 µg) at which no side effects were observed. Taking advantage of the finding that NMB induces itch exclusively through NMBR in the spinal cord12, we functionally verified the loss of NMBR neurons by i.t. injection of NMB-induced scratching (NIS). NMB-sap treated mice barely showed scratching behaviors, whereas control mice exhibited robust NIS with a rapid onset of scratching responses (Fig. 4A and B), indicating that NMBR neurons were ablated in the spinal cord. NMB-sap-treated mice showed significantly attenuated scratching behaviors to i.d. injections of histamine, 48/80, 5-HT, CQ, SLIGRL and BAM8-22 (Fig. 4B). These data demonstrate an important role of NMBR+ neurons in itch transmission. Unexpectedly, molecular analysis using IHC revealed that the number of Nmbr-eGFP+ neurons in the superficial dorsal horn was significantly reduced, but not completely lost, in NMB-sap treated mice compared to control mice (Fig. 4C and D). By contrast, expression of GRPR, NK1R, PKCγ, CGRP/IB4 and TRPV1 was comparable to control, confirming the specificity of the ablation of NMBR neurons by NMB-sap (Fig. 4E–I). To examine whether a partial loss of Nmb-eGFP cells was attributable to the low dose of Nmb-sap we used, we repeated i.t. NMB-sap injection three times using the same dose and found that the remaining eGFP cells were not affected. Taken together with the absence of NIS in mice treated with NMB-sap, the most probably explanation is that some Nmb-eGFP cells do not express NMBR protein, despite the fact that spinal Nmbr-eGFP largely recapitulates expression of Nmbr mRNA12.

Attenuated scratching behaviours after ablation of spinal NMBR+ neurons. (A) NMB-induced scratching behavior was abolished in mice treated with NMB-sap comparing with control mice. P < 0.0001, repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttests. n = 6 per group. (B) Mice treated with NMB-sap (1–2 µg, i.t.) showed deficits in scratching response to NMB (P = 0.0004), histamine (P = 0.0240), 48/80 (P = 0.0487), 5-HT (P = 0.0301), CQ (P = 0.0269), SLIGRL (P = 0.0409), and BAM8-22 (P = 0.0076). n = 6–9 per genotype. (C and D) Quantified data (C) and representative images (D) to show decreased number of NMBR-eGFP neurons in the superficial dorsal horn of NMB-sap-treated mice. (E–G), IHC images to show GRPR neurons (E), NK1R neurons (F) and PKCγ neurons (G) were not affected by NMB-sap treatment. (H and I) IHC images of CGRP/IB4 (H) and TRPV1 (I) to show normal projection of primary afferents in NMB-sap-treated mice. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, versus control. Unpaired t test in (B and C).

In contrast to notable deficits in itch transmission, NMB-sap treated mice exhibited normal behavioral responses to acute mechanical stimuli as tested by von Frey (Fig. 5A) and Randall Selitto tests (Fig. 5B). NMB-sap treatment also failed to affect behavioral responses to thermal stimuli as tested by Hargreaves test (Fig. 5C), hotplate test (Fig. 5D) and tail immersion (Fig. 5E). We also examined inflammatory pain behaviors of NMB-sap treated mice and found normal nocifensive behaviors evoked by i.pl. injection of formalin (Fig. 5F), capsaicin (Fig. 5G) and mustard oil (Fig. 5H). I.pl. injection of CFA induced comparable mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity between NMB-sap-treated mice and control mice (Fig. 5I and J).

Pain behaviors of NMB-sap-treated mice. (A and B) Mechanical pain threshold was comparable between NMB-sap mice and control mice as tested by non-noxious von Frey assay (P = 0.5143) (A) and noxious Randall Selitto assay (P = 0.0523) (B). n = 6–10 per group. (C–E) NMB-sap mice showed normal response to thermal stimuli in Hargreaves (P = 0.9337) (C), hotplate (P = 0.7280) (D) and tail-immersion tests (P = 0.1223) (E). n = 6–10 per group. (F–H) Licking/flinching responses induced by formalin (P = 0592 for phase 1, P = 0.4978 for phase 2) (F), capsaicin (2 µg, i.pl.) (P = 0.7076) (G) and mustard oil (P = 0.7946) (H) were not different between NMB-sap mice and control mice. n = 7–8 per group. (I and J) CFA induced comparable hypersensitivity to mechanical (I) and thermal stimuli (J) in both control mice and NMB-sap mice. n = 6 per group. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. Unpaired t test in (A-C and F-H), two-way repeated measure ANOVA in (D, E, I and J).

GRPR neurons receive glutamatergic input from NMBR neurons

Next, we examined the electrophysiological properties of NMBR neurons by patch-clamp recording of Nmbr-eGFP neurons in spinal cord slice preparations (Fig. 6A). The delayed firing pattern was observed in most eGFP neurons, independent of their resting potential (−60 or −70 mV) (Fig. 6B). This observation is consistent with the finding that most NMBR neurons are glutamatergic, suggesting that they are primarily excitatory12. Application of NMB (1 µM) caused subthreshold depolarizations in most NMBR neurons (Fig. 6C and E). Increasing the NMB application to 2 µM, NMB induced depolarization and action potential (AP) firing in most NMBR neurons (Fig. 6D and E). The membrane depolarization induced by NMB was accompanied by a significant increase in input resistance at both concentrations, suggesting that the inhibition of a membrane conductance was involved (Fig. 6F). It is worth noting that irrespective of the concentration of NMB application, we found that a significant percentage of eGFP+ neurons did not respond to NMB, consistent with the observation that some eGFP+ neurons remained after NMB-sap treatment. Considering that most Nmbr-eGFP cells express Nmbr transcript12, these findings further support the idea that not all Nmbr mRNA are translated into NMBR protein, an observation reminiscent of expansion of Grpr-eGFP expression in chronic itch conditions15.

NMB depolarizes NMBR neurons and increases neuronal excitability. (A) Schematic diagram depicting the patch clamp approach performed on transverse sections of lumbar spinal cord of Nmbr-eGFP mice, where eGFP neurons are mainly located in laminae I-II (green color). (B) Characterization of firing patterns recorded from Nmbr-eGFP neurons. Positive current steps of 5–10 pA (500 ms) were applied while recording in current clamp. Delayed firing pattern was dominant (20/46). (C and D) Representative traces from the recording of NMBR neurons after NMB application. NMB was applied at the neuron resting potential (indicated in red), ranging from −59 to −70 mV. 1 µM NMB induces a subthreshold depolarization (mean depolarization: 4.9 ± 0.6 mV) (18/53), while 2 µM NMB causes action potential firing (mean depolarization: 11.1 ± 2.1 mV) (6/8). (E) Membrane potential changes observed in subpopulations of NMBR neurons responsive to NMB, at 2 different concentrations. In red: membrane depolarizations observed in neurons that fired AP following NMB application. (F) Input resistance changes induced by NMB in a subpopulation of responsive Nmbr-eGFP neurons. NMB caused a significant increase of input resistance at 1 µM (P = 0.0011) and 2 µM (P = 0.0127). n = 18 for 1 µM NMB, and n = 6 for 2 µM NMB. Values in (E and F) are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, versus control, paired t test.

We tested whether NMBR neurons could be part of microcircuits that function upstream of GRPR neurons. Because NMB does not activate GRPR neurons directly in vivo 12, it is possible to examine the effect of NMB on GRPR neurons indirectly by recording Grpr-eGFP neurons12 (Fig. 7A). Indeed, NMB significantly increased the frequency of spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs), with minimal desensitization effect 10 min after the 1st application (Fig. 7B, C and F). The increase in sEPSCs induced by NMB was blocked by CNQX, a non-NMDA ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonist (Fig. 7D and F). As an increased sEPSC frequency reflects enhanced glutamatergic transmission33,34, together these data suggest that the connectivity between NMBR neurons and GRPR neurons is glutamatergic in nature.

NMBR neurons provide glutamatergic input to GRPR neurons. (A) Schematic diagram of the dorsal horn depicting patch clamp recordings of Grpr-eGFP neurons that receive synaptic connections from interneurons that express NMBR. (B) NMB (1 µM) increases the frequency of sEPSCs recorded from a GRPR neuron (Voltage clamp recording), a 2nd application of NMB increases sEPSC frequency with minimal desensitization. Lower traces depict sEPSCs on an expanded time scale for control and NMB applications. (C) Scatter plot of normalized sEPSC frequencies, obtained from a sample of 22 GRPR neurons responsive to NMB (22/75). NMB causes an average frequency change of 621 ± 231% (mean frequency in control: 1.5 ± 0.4 vs 6.2 ± 1.8 Hz in NMB, n = 22). (D) CNQX (50 µM) completely blocked sEPSCs recorded from a GRPR neuron responding to NMB and prevented any effect of a 2nd NMB application. Lower traces depict sEPSCs on an expanded time scale for control and NMB applications. (E) TTX (1 µM) totally abolished the NMB-induced increase in frequency of sEPSCs recorded from a GRPR neuron. Lower traces depict EPSCs on an expanded time scale for control, 1st NMB application and TTX NMB. (F) Representative traces depicting the effect of NMB on sEPSC frequency over time for two successive NMB applications. Green plot represents two NMB treatments. Red and blue plots represent NMB treatment followed by TTX and CNQX, respectively, obtained from 2 different neurons. (G) Application of NMB in the presence of TTX does not affect the frequency (P = 0.85) or the amplitude of miniature EPSCs (P = 0.12). Paired t test. n = 6. (H and I) A representative trace recorded (H) in voltage clamp from a GRPR neuron, showing the increase of sEPSC frequency induced by histamine (200 µM), followed by NMB (1 µM). The time course of both responses is illustrated in (I). Mean EPSC frequency determined for histamine-responsive neurons (11/47): 1.1 ± 0.3 Hz in control vs. 3.5 ± 0.6 Hz in histamine.

To determine whether the increase of sEPSC induced by NMB could result from activation of NMBR terminals of primary afferents which contact GRPR neurons28,35,36, we tested the effect of NMB on GRPR neurons in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX), a blocker of voltage-gated sodium channels. Importantly, TTX completely abolished NMB-induced increased frequency of sEPSCs in GRPR neurons (Fig. 7E and F). Under these conditions, no effect of NMB was observed on EPSC frequency or amplitude (Fig. 7G). These results suggest that NMB acts on NMBR neurons through an AP-dependent mechanism to induce the sEPSC frequency increase and in addition excludes a direct effect of NMB on AMPA receptors expressed in GRPR neurons.

Since mice lacking NMB had selective deficits in histaminergic itch, we assessed whether histamine could also increase the frequency of sEPSCs recorded from GRPR neurons, possibly by activating histamine sensitive primary afferents and increasing the excitatory drive to NMBR neurons. Indeed, histamine caused a significant increase of sEPSC frequency in a subpopulation of GRPR neurons, for the majority of which have also responded to NMB (Fig. 7H and I). The similarities between the two responses (time course and the proportion of responsive neurons) suggest that histamine and NMB could activate the same synaptic pathway, leading to an increased excitability of NMBR neurons that, in turn, release glutamate onto GRPR neurons.

Discussion

Spinal GRP and NMB encode itch-specific information

We found normal acute thermal, mechanical and chemical pain behaviors of mice lacking either GRP/NMB or GRPR/NMBR, suggesting that the NMB-NMBR and GRP-GRPR pathways do not compensate for each other in nociceptive processing. While NMBR and GRPR are expressed in discrete areas of the brain37, we did not find evidence suggesting that NMB-NMBR/GRP-GRPR signaling are major players in nociceptive processing in the nervous system. The present study represents one of the first kinds which comprehensively analyze pain behaviors of DKO mice lacking two related peptides or receptors. Together with previous findings that GRP/NMB can induce dose-dependent and itch-related scratching behavior upon i.t. injection6,12, the data markedly strengthen the notion that GRP and NMB are itch-specific neuropeptides. In contrast, other neuropeptides, including SP, CGRP and B-type natriuretic peptide, have been implicated in transmitting pain information from DRGs to the spinal cord, but their sites of action (interneurons vs. projection neurons; excitatory vs. inhibitory) are unclear3,9,11,38,39. Although a neuropeptide may be involved in both pain and itch, most likely it may exert opposing function in a state-dependent manner. An activation of the central itch circuit by an itch peptide may inhibit pain, either by interneuron-mediated cross-inhibition mechanisms40, by discrete subpopulations of neurons-mediated independent mechanisms8, or by the supraspinal descending control pathway41.

Considering the low dose of GRP/NMB used in dose-related response as well as scratching evoked immediately after i.t. injection6,23, GRP/NMB are likely to activate GRPR/NMBR directly to transmit itch information. Interestingly, it seems that the roles of NMB and GRP in itch transmission are mostly non-overlapping. This is consistent with differential expression patterns of GRP-GRPR and NMB-NMBR in both sensory neurons and spinal cord. GRPR is expressed in the superficial laminae I-II, while NMBR is mostly enriched in the lamina II inner layer6,12,28.

An impaired histamine-induced itch in Nmb KO mice confirms the role of NMB-NMBR signaling in histamine itch12. A cross-inhibition model was proposed to explain seemingly normal histamine-induced itch response exhibited by Nmbr KO mice as NMB may act as a functional antagonist for GRPR12. In contrast to Nmbr KO mice, the specific requirement for histamine-induced itch in Nmb KO mice was not masked. Such mismatched phenotypes indicate that lack of the ligand vs. the receptor may give rise to distinct cross-signaling dynamics. Consistent with this model, similar phenotypes in CQ- and histamine-induced itch between Grp and Grpr KO mice were observed.

The observation that Grp/Nmb DKO mice still retained scratching behaviors in response to 48/80, CQ and SLIGRL suggests the involvement of additional neurotransmitters in itch transmission. Glutamate has been shown to be required for relaying histamine-, but not required for CQ-induced itch from DRGs to the spinal cord42,43. In contrast, Akiyama et al. showed that i.t. injection of CNQX partially attenuated CQ-induced itch11, implicating the role of glutamate in the process. How to reconcile these seemingly conflicting results? One explanation is that i.t. CNQX may attenuate CQ-induced itch by a blockade of glutamatergic transmission from NMBR neurons, which are activated by GRP released from primary afferents, to GRPR neurons (Fig. 8). Thus, glutamate participates in histamine- and CQ-induced itch through peripheral and central mechanisms, respectively. Consistently, we found that GRPR neurons receive monosynaptic glutamatergic EPSCs evoked by primary afferent stimulation. Thus, glutamatergic transmission is also directly involved in pruritogen-dependent itch transmission from pruriceptors in sensory neurons to GRPR neurons in the spinal cord.

(A) A diagram depicting discrete pruritogenic information transmitted by GRP and NMB from sensory neurons to the dorsal horn, respectively. (B) A hypothetic model depicting two major itch-specific neuronal pathways that transmit itch information from DRGs to the brain via the spinal GRPR neurons. GRP fibers project to GRPR neurons that are located mainly in laminae I-II, while NMB fibers project to NMBR neurons, mostly distributed in lamina II, which relay itch information to GRPR neurons using glutamate as a transmitter. Both GRP and NMB fibers may also use glutamate as a transmitter, depending on the type of pruritogen. GRP can also activate NMBR neurons weakly. GRPR neurons and NMBR neurons form a feed forward loop in which NMBR neurons receive and amplify itch signals from GRPR neurons and send them back to GRPR neurons that function as the last output sending itch information to projection neurons. Glu: glutamate.

NMBR neurons function upstream of GRPR neurons in itch transmission

Our studies suggest that NMBR neurons are required for itch, but not pain transmission, and NMBR neurons function upstream of GRPR neurons. Consistent with the finding that NMBR neurons are mostly excitatory12, they exhibited mostly a delayed firing pattern, which is mediated by the presence of the A-type potassium current, and is mainly associated with lamina II excitatory interneurons44,45,46. NMB application induced membrane depolarization and, in some cases, action potential firing, accompanied by an increase of input resistance. The absence of an increase in sEPSC frequency and/or amplitude in GRPR neurons in the presence of TTX suggests that NMB may induce action potential-dependent glutamate release by NMBR neurons to promote synaptic excitation of GRPR neurons. Together with the behavioral observation suggesting that NMB functions exclusively on NMBR neurons in vivo 12, these data supply further evidence supporting the idea that NMB excites postsynaptic NMBR neurons directly rather than indirectly through presynaptic terminals of primary afferents. The connectivity between different subsets of excitatory interneurons in dorsal horn has been reported with uncharacterized physiological relevance46,47. Our finding, in contrast, is the first electrophysiological evidence illustrating the communication from NMBR neurons to GRPR neurons to transmit itch (Fig. 8).

NMBR neurons are required for a wide range of pruritogenic stimuli, including histaminergic and nonhistaminergic itch, which contrasts with a more restricted role of NMB-NMBR signaling in histamine, 48/80 and 5-HT-induced itch. The finding that 14% of NMB and GRP fibers overlap suggests that NMBR neurons can additionally receive direct inputs from GRP afferents12, making it possible for GRP to function as a partial agonist to transmit CQ, SLIGRL and BMA-22-induced itch via NMBR neurons12. On the other hand, it has been shown that GRPR neurons receive direct synaptic contacts with GRP fibers and Mrgpra3 fibers28,35,36. Since NMB is expressed in both CGRP and IB4 fibers, it is conceivable that NMB and GRP afferents could simultaneously target both NMBR and GRPR neurons directly to trigger concurrent activation in response to a specific pruritogen12 (Fig. 8B). Together, we propose that two itch-specific neuronal pathways exist between sensory neurons and GRPR neurons as the final output in the spinal cord: an indirect NMB/GRP-NMBR-GRPR neuronal pathway and a direct GRP-GRPR neuronal pathway (Fig. 8B). A wide range of pruritogens can be detected by different subsets of sensory neurons26,48,49,50,51,52, followed by using GRPR neurons as a central hub for further process3. Overall, NMBR neurons play a role in itch transmission compared to GRPR neurons.

In summary, NMB and GRP appear to encode discrete itch information and NMBR neurons represent a novel itch-specific circuit which is only partially required for relaying both histaminergic and non-histaminergic itch. Together, they constitute functionally distinct but interconnected microcircuits for integrating and transmitting itch information from primary afferents to the brain. Identification of NMBR neurons as an itch circuit helps a deeper understanding of the coding logic of itch transmission in the spinal cord.

Materials and methods

Mice

Male mice between 7 and 12 weeks old were used for experiments. C57BL/6 J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (http://jaxmice.jax.org/strain/013636.html). C57BL/6 J mice, Grp KO15, Nmb KO, Nmbr KO mice53, Grpr KO mice54 and their respective WT littermates were used. Also Nmbr KO mice were crossed with Grpr KO mice to generate Nmbr/Grpr DKO mice and Nmb KO mice were crossed with Grp KO mice to generate Nmb/Grp DKO mice. All mice were housed under a 12 h light/dark cycle with food and water provided ad libitum. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and the International Association for the Study of Pain and were approved by the Animal Studies Committee at Washington University.

Generation and genotyping of Nmb KO mice

Briefly, an Nmb targeting vector was generated by bacterial recombineering approach as previously described55. Mouse genomic 129/SvJ DNA was obtained from Sanger Institute (UK). The linearized targeting plasmid was electroporated into AB1 ES cells. Two independently targeted ES cell clones, identified by Southern blot analysis using external probes, were injected into C57BL/6 J blastocysts to generate chimeric mice. Male chimeras were mated with C57BL/6 J females to produce heterozygous mice, which were subsequently mated to produce Nmb KO mice and WT littermates (Nmb +/+). The primers used for PCR genotyping were NMB-F (5′ UTR): 5′-GGACGATGCCATAAGCACGCGAGTGTGGTG-3′, GFP-R: 5′-CGGTGGTGCAGATGAACTTCAGGGTCAGCT-3′ and NMB-R (exon 1): 5′-GACTGCAGGAGCTCCGCTACCAAGAGCCTC-3′. Primer pair of NMB-F and NMB-R detects WT band of 470 bp. The band is absent in Nmb KO mice without exon 1. Primer pair NMB-F and GFP-R detects GFP band of 370 bp only in Nmb KO mice and heterozygous mice.

Drugs and reagents

Dose of drugs and injection routes are indicated in figure legends. Histamine, 48/80, 5-HT, CQ, formalin, capsaicin, MO and Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). GRP18-27 and NMB were from Bachem. SLIGRL, bovine adrenal medulla 8–22 (BAM8-22) and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP8–37) were purchased from GenScript. Capsaicin was initially dissolved in ethanol followed by a further dilution in sterile saline. The final concentration for ethanol was 2%. Other chemicals were dissolved in sterile saline. Morphine solution (15 mg/ ml) was from WEST-WARD (Eatontown, NJ) and was diluted in sterile saline. NMB-saporin (2 µg/µl) was from Advanced Targeting Systems (San Diego, CA) and diluted in sterile saline.

Behavioral tests

Behavioral tests were videotaped (HDR-CX190, Sony) from a side angle. The videos were played back on computer and the quantification of mice behaviors was done by persons who were blinded to the treatments and genotypes. Hind limb scratching behavior towards the injected area was observed for 30 min with 5 min intervals. One bout of scratch was defined as a lifting of the hind limb to the injection site and then replacing of the limb back to the floor or to the mouth, regardless of how many scratching strokes take place in between6.

Acute scratching behavior

All behavioral tests were performed during the light cycle. Briefly, the injection area was shaved two days before experiments. Prior to the experiments, each mouse was placed in a plastic arena (10 × 11 × 15 cm) for 30 min to acclimate. Mice were briefly removed from the chamber and intradermally injected at the back of the neck.

Mechanical sensitivity

Mechanical sensitivity was assessed using von Frey assay and Randall-Selitto assay. For von Frey assay a set of calibrated von Frey filaments (Stoelting) were used. Each filament was applied 5 consecutive times and the smallest filament that evoked reflexive flinches of the paw on 3 of the 5 trials was taken as paw withdrawal threshold. To measure tail flick threshold to noxious mechanical stimulation, a Randall-Selitto Analgesy-meter was used. Mice were held gently and the force was applied directly to the dorsal surface of the tail 2.5 cm from its end via a cone-shaped plunger. The tail flick threshold was defined as the force, in grams, at which the mouse attempts to flick its tail (cut-off force 250 g).

Thermal sensitivity

Thermal sensitivity was determined using hotplate (50, 52, or 56 °C), Hargreaves and tail immersion assay (48, 50, or 52 °C). For the hotplate test, the latency for the mouse to lick its hindpaw or jump was recorded. For the Hargreaves test, thermal sensitivity was measured using a Hargreaves-type apparatus (IITC Inc.). The latency for the mouse to withdraw from the heat source was recorded. For the warm water tail immersion assay mice tails were dipped beneath the warm water (48, 50 or 52 °C) in a temperature-controlled water bath (IITC Inc.). The latencies to withdrawal were measured with a 20, 15 or 10-sec cutoff, respectively.

Acute pain behavior

Different pruritogens or algogens were intraplantarly injected into the right hindpaws. The duration of licking and flinching of the injected paw was recorded for 60 min after injection for formalin test and in the first 10 min after injection for other drugs. Thermal and mechanical sensitivity of the injected paw was assessed 1 h before and 30~60 min after injection using the Hargreaves and von Frey assay, respectively. For morphine analgesia, morphine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) was given 30 min before administration of other chemicals.

SNI

SNI was carried out according to the procedure described previously29. Briefly, mice were exposed to a cocktail (ketamine, 100 mg/kg and Xylazine, 15 mg/kg) to induce anesthesia. Three terminal branches of sciatic nerve were exposed, and common peroneal and the tibial nerves were cut, leaving the sural nerve intact. Muscle and skin were closed in two layers.

IHC and ISH

Mice were anesthetized (ketamine, 100 mg/kg and Xylazine, 15 mg/kg) and perfused intracardially with PBS pH 7.4 followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Tissues were dissected, post-fixed for 2~4 h, and cryoprotected in 20% sucrose in PBS overnight at 4 °C. Tissues were sectioned in OCT using a cryostat microtome. IHC was performed as described56. Briefly, free-floating frozen sections at 20 μm thickness were blocked in a 0.01 M PBS solution containing 2% donkey serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 followed by incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, washed three times with PBS, secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature and washed again three times. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated Isolectin B4 from Griffonia simplicifolia (IB4, 10 µg/mL; L2895, Sigma) or the following primary antibodies were used, rabbit anti-CGRPα (1:3000; AB1971, Millipore; RRID: AB_2313629), guinea pig anti-SP (1:1000; ab10353, Abcam; RRID:AB_297089), guinea pig anti- the transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor (TRPV1) (1:1000; GP14100, Neuromics; RRID:AB_1624142). The secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories including Cyanine 3 (Cy3)- conjugated donkey anti-rabbit or anti-guinea pig IgG (0.5 µg/ml).

ISH was performed using a digoxigenin-labeled cRNA (Roche) antisense probe for Nmb. Briefly, on-slide frozen DRG sections at 20 μm thickness were incubated in prehybridization solution for 3 hours at 65 °C and then incubated with Nmb probe (2 μg/ mL) hybridization solution overnight at 65 °C. After stringency washes, sections were incubated in PBS with 20% sheep serum and 0.1% Tween blocking solution for 3 hours and then incubated with anti-digoxigenin antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (0.5 μg/mL, Roche) in blocking solution overnight at 4 °C. After washing in PBS with 0.1% Tween, sections were incubated in NBT/BCIP substrate solution at room temperature for 2~4 h for colorimetrtic detection. Reactions were stopped by washing in 0.5% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-U microscope. Staining intensities were quantified by an observer blinded to the genotype using ImageJ (version 1.34e, NIH Image). At least 3 mice per group and 10 sections across each tissue were included for statistical comparisons.

Electrophysiology

To study the synaptic input to GRPR neurons, electrophysiological experiments were performed as follows. For tissue preparation: Fresh spinal cord tissue was isolated from Grpr-eGFP mice under control of the Grpr promoter. Mice ages 17–28 days were utilized for experiments. A laminectomy was performed under an ice cold (4 °C) oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) sucrose-based dissection solution (in mM, 209 Sucrose, 2 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 5 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose) The lumbar region of the spinal cord was removed from the spinal column and embedded in agar in preparation for slicing using a vibrating tissue slicer (Leica VT 1000 S). Transverse sections of the lumbar spinal cord were obtained at a thickness of 500 µm and then stored in an incubation chamber containing oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF- containing in mM 130 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.4 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.4 CaCl2, 25 NaHCO3, 10 glucose). For patch clamping: Spinal cord neurons were visualized under an upright microscope (Olympus BX 51) equipped with IR-DIC optics. Neurons expressing eGFP were visualized with 488 nm light (FITC filter). Spinal cord slices were mounted in a chamber (Warner RC 26 G) continuously perfused with ACSF at a rate 2 ml/min. Patch pipettes (WPI-thick wall borosilicate) were pulled (Sutter P97) to a resistance of 3–5 MΩ. Patch pipettes contained (in mM, 130 Kgluconate, 10 NaCl, 1 MgCl2 0.2 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 1 MgATP, 5 NaGTP). High resistance membrane seals were made between the pipette and the membrane followed by rupture to achieve whole cell configuration. Neurons having a resting membrane potential more negative than −50 mV and an action potential amplitude of at least 80 mV were deemed healthy and viable for experiments. For current clamp experiments in NMBR neurons, firing patterns were tested with a rectangular injection of positive current in steps of 5–10 pA (500 ms). Input resistance was measured from the voltage deflection in response to injection of −20 pA (500 ms) current. NMB applications were made to neurons at resting membrane potential. To quantify excitatory synaptic responses of GRPR neurons, GRPR neurons were voltage clamped (−60 mV) in order to record synaptic currents under basal and NMB conditions. Signals for membrane potential and membrane current were controlled and amplified with a Multiclamp 700 B and Digidata 1550 A and pClamp 10.6 software. The signal for membrane current was low pass filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 10 kHZ. Synaptic events were analyzed in Clampfit 10.6 and Minianalysis (Synaptosoft) software, membrane current traces were plotted using Origin 2015 software.

Statistical analysis

Values are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 6 (v6.0e, GraphPad, San Diego, CA). For comparison between two or more groups, unpaired two-tailed t-test or One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc analysis or Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttest was used. Normality and equal variance tests were performed for all statistical analyses. Analysis of spontaneous EPSCs recorded from GRPR neurons was performed on individual neurons by using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test, in order to compare cumulative distributions of inter-event intervals or amplitudes. Neurons were defined as responsive when the K-S test provided a p value < 0.05. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

LaMotte, R. H., Dong, X. & Ringkamp, M. Sensory neurons and circuits mediating itch. Nat Rev Neurosci 15, 19–31, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3641 (2014).

Bautista, D. M., Wilson, S. R. & Hoon, M. A. Why we scratch an itch: the molecules, cells and circuits of itch. Nat Neurosci 17, 175–182, https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3619 (2014).

Barry, D. M., Munanairi, A. & Chen, Z. F. Spinal Mechanisms of Itch Transmission. Neurosci Bull, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-017-0125-2 (2017).

Braz, J., Solorzano, C., Wang, X. & Basbaum, A. I. Transmitting Pain and Itch Messages: A Contemporary View of the Spinal Cord Circuits that Generate Gate Control. Neuron 82, 522–536, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.018 (2014).

Ma, Q. Population coding of somatic sensations. Neurosci Bull 28, 91–99 (2012).

Sun, Y. G. & Chen, Z. F. A gastrin-releasing peptide receptor mediates the itch sensation in the spinal cord. Nature 448, 700–703 (2007).

Sun, Y. G. et al. Cellular basis of itch sensation. Science 325, 1531–1534 (2009).

Liu, X. Y. et al. Unidirectional Cross-Activation of GRPR by MOR1D Uncouples Itch and Analgesia Induced by Opioids. Cell 147, 447–458, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.043 (2011).

Liu, X. Y. et al. B-type natriuretic peptide is neither itch-specific nor functions upstream of the GRP-GRPR signaling pathway. Mol Pain 10, 4, https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-10-4 (2014).

Lagerstrom, M. C. et al. VGLUT2-dependent sensory neurons in the TRPV1 population regulate pain and itch. Neuron 68, 529–542, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.016 (2010).

Akiyama, T., Tominaga, M., Takamori, K., Carstens, M. I. & Carstens, E. Roles of glutamate, substance P, and gastrin-releasing peptide as spinal neurotransmitters of histaminergic and nonhistaminergic itch. Pain 155, 80–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.09.011 (2014).

Zhao, Z. Q. et al. Cross-inhibition of NMBR and GRPR signaling maintains normal histaminergic itch transmission. J Neurosci 34, 12402–12414, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1709-14.2014 (2014).

Wang, X. et al. Excitatory superficial dorsal horn interneurons are functionally heterogeneous and required for the full behavioral expression of pain and itch. Neuron 78, 312–324, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.001 (2013).

Mishra, S. K. & Hoon, M. A. The cells and circuitry for itch responses in mice. Science 340, 968–971, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1233765 (2013).

Zhao, Z. Q. et al. Chronic itch development in sensory neurons requires BRAF signaling pathways. J Clin Invest 123, 4769–4780, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI70528 (2013).

Shiratori-Hayashi, M. et al. STAT3-dependent reactive astrogliosis in the spinal dorsal horn underlies chronic itch. Nat Med 21, 927–931, https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3912 (2015).

Yu, Y. Q., Barry, D. M., Hao, Y., Liu, X. T. & Chen, Z. F. Molecular and neural basis of contagious itch behavior in mice. Science 355, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aak9748 (2017).

Fleming, M. S. et al. The majority of dorsal spinal cord gastrin releasing peptide is synthesized locally whereas neuromedin B is highly expressed in pain- and itch-sensing somatosensory neurons. Mol Pain 8, 52, https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-8-52 (2012).

Wada, E., Way, J., Lebacq-Verheyden, A. M. & Battey, J. F. Neuromedin B and gastrin-releasing peptide mRNAs are differentially distributed in the rat nervous system. J Neurosci 10, 2917–2930 (1990).

Snider, W. D. & McMahon, S. B. Tackling pain at the source: new ideas about nociceptors. Neuron 20, 629–632 (1998).

Cowan, A. In Bombesin-like peptides in health and disease Vol. 547 (ed Melchiorri, Y., Tache, P. and Negri, L.) 204-209 (The New York Academy of Sciences, 1988).

Bishop, J. F., Moody, T. W. & O’Donohue, T. L. Peptide transmitters of primary sensory neurons: similar actions of tachykinins and bombesin-like peptides. Peptides 7, 835–842 (1986).

Sukhtankar, D. D. & Ko, M. C. Physiological function of gastrin-releasing Peptide and neuromedin B receptors in regulating itch scratching behavior in the spinal cord of mice. PLoS One 8, e67422, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067422 (2013).

Kroog, G. S., Jensen, R. T. & Battey, J. F. Mammalian bombesin receptors. Med Res Rev 15, 389–417 (1995).

Mishra, S. K., Holzman, S. & Hoon, M. A. A nociceptive signaling role for neuromedin B. J Neurosci 32, 8686–8695, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1533-12.2012 (2012).

Liu, Q. et al. Sensory neuron-specific GPCR Mrgprs are itch receptors mediating chloroquine-induced pruritus. Cell 139, 1353–1365 (2009).

Hokfelt, T. et al. Neuropeptides–an overview. Neuropharmacology 39, 1337–1356 (2000).

Barry, D. M. et al. Critical evaluation of the expression of gastrin-releasing peptide in dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord. Mol Pain 12, https://doi.org/10.1177/1744806916643724 (2016).

Decosterd, I. & Woolf, C. J. Spared nerve injury: an animal model of persistent peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain 87, 149–158 (2000).

Akiyama, T., Carstens, M. I. & Carstens, E. Facial injections of pruritogens and algogens excite partly overlapping populations of primary and second-order trigeminal neurons in mice. J Neurophysiol 104, 2442–2450, https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00563.2010 (2010).

Shimada, S. G. & LaMotte, R. H. Behavioral differentiation between itch and pain in mouse. Pain 139, 681–687, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2008.08.002 (2008).

LaMotte, R. H., Shimada, S. G. & Sikand, P. Mouse models of acute, chemical itch and pain in humans. Exp Dermatol 20, 778–782, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01367.x (2011).

Yoshimura, M. & Nishi, S. Excitatory amino acid receptors involved in primary afferent-evoked polysynaptic EPSPs of substantia gelatinosa neurons in the adult rat spinal cord slice. Neurosci Lett 143, 131–134 (1992).

Yang, K., Kumamoto, E., Furue, H. & Yoshimura, M. Capsaicin facilitates excitatory but not inhibitory synaptic transmission in substantia gelatinosa of the rat spinal cord. Neurosci Lett 255, 135–138 (1998).

Satoh, K. et al. Effective synaptome analysis of itch-mediating neurons in the spinal cord: A novel immunohistochemical methodology using high-voltage electron microscopy. Neurosci Lett 599, 86–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2015.05.031 (2015).

Han, L. et al. A subpopulation of nociceptors specifically linked to itch. Nat Neurosci 16, 174–182, https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3289 (2013).

Wada, E., Wray, S., Key, S. & Battey, J. Comparison of gene expression for two distinct bombesin receptor subtypes in postnatal rat central nervous system. Mol Cell Neurosci 3, 446–460 (1992).

Rogoz, K., Andersen, H. H., Lagerstrom, M. C. & Kullander, K. Multimodal use of calcitonin gene-related Peptide and substance p in itch and acute pain uncovered by the elimination of vesicular glutamate transporter 2 from transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily v member 1 neurons. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 34, 14055–14068 (2014).

Andoh, T., Nagasawa, T., Satoh, M. & Kuraishi, Y. Substance P induction of itch-associated response mediated by cutaneous NK1 tachykinin receptors in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 286, 1140–1145 (1998).

Ross, S. E. et al. Loss of Inhibitory Interneurons in the Dorsal Spinal Cord and Elevated Itch in Bhlhb5 Mutant Mice. Neuron 65, 886–898 (2010).

Zhao, Z. Q. et al. Descending Control of Itch Transmission by the Serotonergic System via 5-HT1A-Facilitated GRP-GRPR Signaling. Neuron 84, 821–834, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.003 (2014).

Liu, Y. et al. VGLUT2-dependent glutamate release from nociceptors is required to sense pain and suppress itch. Neuron 68, 543–556, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.008 (2010).

Koga, K. et al. Glutamate acts as a neurotransmitter for gastrin releasing peptide-sensitive and insensitive itch-related synaptic transmission in mammalian spinal cord. Mol Pain 7, 47, https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-7-47 (2011).

Heinke, B., Ruscheweyh, R., Forsthuber, L., Wunderbaldinger, G. & Sandkuhler, J. Physiological, neurochemical and morphological properties of a subgroup of GABAergic spinal lamina II neurones identified by expression of green fluorescent protein in mice. J Physiol 560, 249–266, https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2004.070540 (2004).

Yasaka, T., Tiong, S. Y., Hughes, D. I., Riddell, J. S. & Todd, A. J. Populations of inhibitory and excitatory interneurons in lamina II of the adult rat spinal dorsal horn revealed by a combined electrophysiological and anatomical approach. Pain 151, 475–488, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.008 (2010).

Lu, Y. & Perl, E. R. Modular organization of excitatory circuits between neurons of the spinal superficial dorsal horn (laminae I and II). The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 25, 3900–3907 (2005).

Santos, S. F. A., Rebelo, S., Derkach, V. A. & Safronov, B. V. Excitatory interneurons dominate sensory processing in the spinal substantia gelatinosa of rat. The Journal of physiology 581, 241–254 (2007).

Imamachi, N. et al. TRPV1-expressing primary afferents generate behavioral responses to pruritogens via multiple mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 11330–11335 (2009).

Roberson, D. P. et al. Activity-dependent silencing reveals functionally distinct itch-generating sensory neurons. Nat Neurosci, https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3404 (2013).

Kim, S. et al. Facilitation of TRPV4 by TRPV1 is required for itch transmission in some sensory neuron populations. Sci Signal 9, ra71, https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.aaf1047 (2016).

Wilson, S. R. et al. TRPA1 is required for histamine-independent, Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor-mediated itch. Nat Neurosci 14, 595–602, https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2789 (2011).

McCoy, E. S. et al. Peptidergic CGRPalpha primary sensory neurons encode heat and itch and tonically suppress sensitivity to cold. Neuron 78, 138–151, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.030 (2013).

Ohki-Hamazaki, H. et al. Functional properties of two bombesin-like peptide receptors revealed by the analysis of mice lacking neuromedin B receptor. J Neurosci 19, 948–954 (1999).

Hampton, L. L. et al. Loss of bombesin-induced feeding suppression in gastrin-releasing peptide receptor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95, 3188–3192 (1998).

Liu, P., Jenkins, N. A. & Copeland, N. G. A highly efficient recombineering-based method for generating conditional knockout mutations. Genome Res 13, 476–484 (2003).

Zhao, Z. Q. et al. Central serotonergic neurons are differentially required for opioid analgesia but not for morphine tolerance or morphine reward. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 14519–14524 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ohki-Hamazaki for Nmbr +/− mice and L. H., K. S., for technical support. We also thank the Chen lab members for comments. D.M.B. has been supported by W.M. Keck Fellowship and NIH-NIDA T32 Training Grant (5T32DA007261-23). The project has been supported by the NIH grants 1R01AR056318-06, R21 NS088861-01A1, R01NS094344, R01 DA037261-01A1 and R56 AR064294-01A1 (Z. F. C).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.F.C. conceived the project and designed the experiments; L.W., H.J., X.Y.L., K.F.S., J.H.J., Y.S., J.H.P., Q.T.M., and P.M. performed behavioral tests. D.M.B., X.T.L., for IHC studies, J.J., and R.B., for electrophysiological recording and data analysis. R.K., J.Y. and A.T. contributed to the work. X.Y.L., D.M.B., J.J., R.B., and Z.F.C wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wan, L., Jin, H., Liu, XY. et al. Distinct roles of NMB and GRP in itch transmission. Sci Rep 7, 15466 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15756-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15756-0

This article is cited by

-

Molecular recognition of itch-associated neuropeptides by bombesin receptors

Cell Research (2022)

-

Neuronal pentraxin 2 is required for facilitating excitatory synaptic inputs onto spinal neurons involved in pruriceptive transmission in a model of chronic itch

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Exploration of sensory and spinal neurons expressing gastrin-releasing peptide in itch and pain related behaviors

Nature Communications (2020)

-

A spinal neural circuitry for converting touch to itch sensation

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Pain Inhibits GRPR Neurons via GABAergic Signaling in the Spinal Cord

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.