Abstract

The dynamics of net primary productivity (NPP) and its partitioning to the aboveground versus belowground are of fundamental importance to understand carbon cycling and its feedback to climate change. However, the responses of NPP and its partitioning to precipitation gradient are poorly understood. We conducted a manipulative field experiment with six precipitation treatments (1/12 P, 1/4 P, 1/2 P, 3/4 P, P, and 5/4 P, P is annual precipitation) in an alpine meadow to examine aboveground and belowground NPP (ANPP and BNPP) in response to precipitation gradient in 2015 and 2016. We found that changes in precipitation had no significant impact on ANPP or belowground biomass in 2015. Compared with control, only the extremely drought treatment (1/12 P) significantly reduced ANPP by 37.68% and increased BNPP at the depth of 20–40 cm by 80.59% in 2016. Across the gradient, ANPP showed a nonlinear response to precipitation amount in 2016. Neither BNPP nor NPP had significant relationship with precipitation changes. The variance in ANPP were mostly due to forbs production, which was ultimately caused by altering soil water content and soil inorganic nitrogen concentration. The nonlinear precipitation-ANPP relationship indicates that future precipitation changes especially extreme drought will dramatically decrease ANPP and push this ecosystem beyond threshold.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The terrestrial ecosystem has experienced frequent and extreme precipitation events during the last five decades1,2,3,4,5, which is projected to become even more frequent and severe during the remainder of the 21st century6,7. Because precipitation is a primary determinant of plant growth, its variation has profound impacts on net primary productivity (NPP) of the terrestrial ecosystems8,9. Thus, a robust understanding of the relationship between precipitation and NPP is critical but a big challenge for better prediction of carbon cycle in response and feedback to climate change10.

The precipitation-NPP relationship has been studied by spatial approach, temporal approach, and manipulative experiments. Spatial approach basically uses precipitation transect to relate aboveground NPP (ANPP) with precipitation changes along a precipitation gradient. The spatial models mostly show that ANPP increases linearly with mean annual precipitation in meadow steppes11, temperate grasslands12 and alpine grasslands13. The temporal studies relate time series of ANPP and annual precipitation in a single site and also find linear relationship between them but with lower slopes and regression coefficients than spatial models14,15. Because the constraint of plant communities and soil biogeochemistry, temporal models in a single site are more preferred over spatial models to forecasts precipitation effects on ANPP14. Recently, Knapp, et al.16 proposed a double asymmetry hypothesis, which used a nonlinear model to fit precipitation-ANPP relationship. Specifically, when spanning large gradients in precipitation or in extreme precipitation years, the relationship of ANPP and precipitation will display a positive or negative asymmetry. However, few studies are conducted to test or support this nonlinear relationship17,18. Although some manipulative experiments have been set up to examine the relationship between precipitation and ANPP, the relationship is restricted by the limited range of rainfall that mostly have two or three levels of precipitation treatments19. To gain empirical evidence of ANPP responses to large variations in precipitation, it is imperative to conduct field precipitation gradient experiments, with multiple levels of precipitation, especially the extreme precipitation condition.

Compared with ANPP, belowground production is even less understood, largely owing to the methodological difficulties of observation and measurement of root biomass20. In grasslands, belowground production contributes more than half of total primary production and is the major input of organic matter into soil21,22. Therefore, understanding the relationship of belowground production and precipitation is crucial to improve our knowledge of NPP variability in response to future global precipitation regimes. There are a few studies on the responses of belowground biomass (BGB) to precipitation change, but generate large debates. For example, a transect study in the Inner Mongolia grassland showed a linear relationship of BGB with precipitation gradient of 170 mm to 370 mm23. Nevertheless, a transect study along a precipitation gradient from 430 mm to 1200 mm in the Great Plains found that BGB were largely constant12. Only a few manipulative experiments were conducted to examine belowground NPP (BNPP) response to precipitation changes24,25,26, but none of them studied the response to a precipitation gradient.

The partitioning of BNPP associated with ANPP, commonly defined as f BNPP, is a critical variable reflecting plant growth strategy under changing environmental conditions27,28. f BNPP is also a crucial parameter of terrestrial ecosystem carbon modeling, providing important constraints on the calibration and testing of dynamic carbon-cycling models29,30. Based on ‘functional equilibrium’ of biomass allocation, plants are assumed to allocate more biomass towards roots under limited water condition31. However, due to the limited studies on BNPP, how f BNPP would respond to precipitation gradient is highly uncertain.

Responses of ANPP and BNPP to precipitation changes can be attributable to changes in abiotic factors of soil water content, soil temperature, and soil available nitrogen32,33,34 and the biotic changes in species composition or carbon allocations. Soil has complicated physical and biological characteristics, which will determine the water holding capacity and thus influence water availability that not necessarily reflects precipitation changes35. Meanwhile, precipitation changes will influence soil temperature through changing soil evaporation and plant transpiration36. Water addition usually decreases soil temperature due to soil moisture increase37. In addition, rate of nitrogen mineralization is higher in wet than dry condition, leading to changes in soil nitrogen availability38,39. Moreover, different plant functional types have various sensitivities to precipitation changes32, thus species composition influences NPP response as well. However, how these processes or mechanisms play roles along precipitation gradient are not well quantified or understood yet in specific studies.

The Tibetan Plateau is one of the most sensitive areas in response to global climate change40,41. Precipitation strongly determines NPP variations in this area because precipitation gradient characterizes not only vegetation distribution but also soil nitrogen conditions42. In a transect study in the Tibetan grasslands, both aboveground biomass and belowground biomass were positively correlated with soil moisture43. A temporal study in southeast of Tibetan Plateau also showed ANPP was linearly correlated with annual precipitation across years44. However, few studies have been done to examine responses of NPP and its partitioning along a precipitation gradient in Tibetan Plateau. In this study, by using a precipitation gradient experiment, we studied responses of ANPP, BNPP and f BNPP to precipitation changes. Specifically, we addressed the following questions: (1) How does ANPP, BNPP and f BNPP respond to changes in precipitation gradient in an alpine meadow? (2) What are the key factors controlling the responses of NPP and its partitioning to precipitation changes?

Results

Precipitation and Soil water content

Ambient precipitation over the entire growing season (from May to September) in our study site changed from 132.74 ± 0.69 mm in 1/12 P treatment to 679.54 ± 28.49 mm in 5/4 P treatment in 2015, and from 15.45 ± 1.36 mm in 1/12 P treatment to 581.22 ± 26.61 mm in 5/4 P treatment in 2016 (Fig. 1a,c).

Treatment-induced changes in monthly precipitation (PPT, mm/yr) (a) and soil water content (SWC, v/v %) at the depth of 10 cm (b) from June to September 2015, and monthly PPT (c) and SWC (d) from May to September 2016. Inserted figure in panel shows the average values of variables under six levels over the growing season, values are mean ± SE. Different letters indicate statistically significant difference between treatments at P < 0.05.

Rainfall manipulation caused significant changes in soil water content (SWC) until August 2015. The average SWC over the growing season in 2015 ranged from 23.81 ± 0.49% in 1/12 P treatment to 29.62 ± 0.79% in 5/4 P treatment (P < 0.0001, Fig. 1b). In 2016, treatments had significant effect on SWC, throughout the whole growing season (P < 0.0001, Fig. 1d). The average SWC in 2016 ranged from 18.95 ± 0.78% under 1/12 P treatment to 32.32 ± 0.66% under 5/4 P treatment. Soil temperature was not significantly changed by the treatments, but the soil inorganic nitrogen (SIN) changed from 12.98 ± 1.31 mg L−1 under 1/12 P treatment to 19.56 ± 3.00 mg L−1 under 5/4 P treatment.

Precipitation effects on ANPP, BGB, BNPP and f BNPP

In 2015, ANPP didn’t vary significantly among treatments (Fig. 2a). However, it significantly varied from 240.80 ± 37.94 g m−2 y−1 under 1/12 P treatment to 423.08 ± 50.77 g m−2 y−1 under 5/4 P treatment in 2016 (P < 0.05, Fig. 2d). ANPP was reduced by 37.68% (P = 0.01) under 1/12 P treatment in 2016. When separating aboveground biomass into different plant functional types, differential responses between grasses and forbs were observed along the precipitation gradient. The precipitation treatments marginally impacted biomass of forbs (P = 0.06), but not on grasses (P = 0.84) in 2016 (Fig. 2f). The lowest forbs biomass was 134.13 ± 17.59 g m−2 y−1 under 1/12 P treatment, and the highest one was 300.61 ± 40.88 g m−2 y−1 under 5/4 P treatment. Neither grasses nor forbs biomass was significantly impacted by precipitation gradient in 2015 (Fig. 2b,c).

No significant effect of precipitation on BGB was observed in 2015 (P = 0.69, Fig. 3a). In 2016, the 1/12 P plots tended to have the highest BNPP and f BNPP among precipitation treatments (Fig. 3b,c). The treatments significantly changed BNPP at the depth of 20–40 cm in 2016 (P = 0.01; Fig. 3b). Specifically, BNPP at 20–40 cm was increased by 80.59% under 1/12 P treatment, 58.75% under 1/4 P treatment and 74.43% under 5/4 P treatment, respectively. However, roots at 20–40 cm only accounted for 7.25% and 11.54% of the total BGB and BNPP, respectively. Thus, total BGB or BNPP at 0–40 cm was not significantly changed by precipitation treatments.

Variation in belowground biomass (BGB) under treatments in 2015 (a), and variation in belowground net primary productivity (BNPP) and f BNPP in 2016 (b,c). Open bars in a, b indicate BGB or BNPP at the depth of 0–20 cm, hatched bars indicate BGB or BNPP at the depth of 20–40 cm, values are mean ± SE.

Relationships of productivity with precipitation amount

There was no significant relationship between precipitation and ANPP across plots in 2015 (Fig. 4a). However, ANPP increased nonlinearly with increasing precipitation in 2016 (P = 0.02, r 2 = 0.26; Fig. 4c). There was no significant relationship of BGB or BNPP with precipitation in either year (Fig. 4b,d).

Factors controlling ANPP changes

The variations of ANPP in 2016 showed positively linear correlation with SWC (P = 0.002; Fig. 5a) and SIN (P = 0.004; Fig. 5b) across plots, whereas no significant relationship was found between ANPP and ST (Fig. 5c). Linear regression analyses demonstrated that SWC and SIN explained 29.97% and 26.37% of the variation in ANPP, respectively. The two factors together could explain 37.00% of changes in ANPP based on the multiple regression analysis (P < 0.01). Unlike grasses, productivity of forbs was sensitive to SWC and SIN, which increased linearly with increasing of SWC and SIN (Fig. 5a,b). SWC and SIN contributed to 22.26% and 20.74% of the variation in forbs biomass, respectively.

Discussion

This study shows how much precipitation is extreme enough to cause a threshold response of ecosystem productivity. The threshold of precipitation for productivity was proposed in previous studies, but it lacks of empirical evidence45,46,47. In this study, we found a significant decrease in ANPP (P = 0.014, Fig. 2d) under 1/12 P treatment in 2016, which quantified the precipitation threshold of ANPP under extreme dry conditions. The nonlinear response of ANPP to precipitation gradient suggests that ANPP will decline strongly in extreme dry conditions, which presents as a negative asymmetric response at extreme low precipitation. The nonlinear relationship was inconsistent with the linear ones commonly reported in previous studies11,12,13. For example, in another manipulative experiment that includes three levels of rainfall reduction (30%, 55%, and 80%) in the Patagonian steppe, the authors found significant linear relationship of ANPP with precipitation amount15. This may be due to that their treatments only cover the linear response stage and may not reach the threshold of the ecosystem. So far, more than 85 precipitation experiments have been conducted in the world48. Due to a narrow range of precipitation, these experiments rarely find the threshold or nonlinear relationship between ANPP and precipitation. This study, to our knowledge, is among the first shows the nonlinear response of ANPP to precipitation gradient by using a manipulative experiment17. It partly supports the double asymmetric hypothesis proposed recently by Knapp, et al.16, and enriches the current understanding on the precipitation-ANPP relationship.

Other treatments hardly affect ANPP, which can be explained as follows. First, plant may reduce stomatal conductance and contents or activities of photosynthetic enzymes to adapt to moderate drought, resulting in mild reduction of ANPP instead of abrupt collapse of ecosystem49. Second, deep soil moisture storage from groundwater, snow accumulation and ablation in the high Zoige Basin may partly compensate the depletion of surface water for plant growth50,51. Our findings also provide the time series of the dynamic responses of ANPP to precipitation changes. Unlike the significant reduction in 2016, ANPP showed no significant differences among treatments even under 1/12 P treatment in 2015. This was probably because the lagged effect of precipitation from 2014 or even before. A previous study demonstrated that current-year production is determined by previous-year precipitation52. The findings indicate that both drought intensity and duration substantially affect ANPP responses to precipitation change.

A significant increase was found in BNPP at the depth of 20–40 cm under 1/12 P and 1/4 P treatments (Fig. 3b), suggesting that plants could allocate more biomass to deep soil to capture the limited resources in order to maximize their growth rate53. Since SWC at the depth of 10 cm decreased dramatically under 1/12 P and 1/4 P treatment, more biomass was allocated to deeper roots to absorb deep soil water. Although BNPP at the depth of 20–40 cm increased, there was no significant difference of BNPP at 0–40 cm between treatments because BNPP at 20–40 cm only accounted for 11.54% of total BNPP on average and BNPP at 0–20 cm didn’t change with precipitation treatments. Previous studies reported contradictory results on the responses of belowground biomass to precipitation change, with an increase or a decline of root biomass under drought condition54,55, which may be due to the various drought intensity and duration among studies. For example, moderate water stress with 51-day treatment can enhance root productivity by a surplus of assimilates that are exported to the roots due to allocation changes55. Whereas a ten-year drought treatment significantly diminishes BNPP54. Moreover, different edaphic and climate conditions between sites also contribute to the differential BNPP response to drought56. In line with our findings, the lack of response of root productivity and biomass to precipitation gradient was reported in temperate grasslands as well12.

Root productivity and biomass are determined by the dynamics of root growth and root death. Root growth of a plant is determined by carbon allocation to BNPP vs. ANPP (i.e., BNPP: ANPP ratio) while root death is related to root turnover times. The lack of response of root productivity or biomass to drought was probably due to an increase in the proportion of carbon allocation to roots and a decrease in turnover of roots with decreasing precipitation57,58. The rising trend in root/shoot ratio under drought may facilitate greater water capture and thus optimize root growth under a dry environment (see the detailed discussion next paragraph). It is proved also by the increasing BNPP at 20–40 cm under extreme drought treatment (Fig. 3b). Some studies also confirmed that many new roots are long and slender under drought conditions59. Root turnover rate was not monitored in this study, but previous studies demonstrated a reduction of root turnover with decreasing precipitation60. In all, compared with ANPP, BNPP has more uncertainty under precipitation changes. Additional studies on the mechanism underlying the effect of precipitation on dynamics of root growth and mortality are needed for better understanding of BNPP changes.

In spite of no significant differences of f BNPP among treatments, the 1/12 P plots tended to have higher f BNPP than other treatments (Fig. 3c). This was probably a consequence of plant adaptation to extreme dry condition by regulating proportion of the biomass allocation toward belowground. Some previous studies confirmed that plants increase f BNPP to optimize growth under drought conditions, likely resulted from changes in the relative importance of limiting resources (such as water, light, nutrients)12,34. However, some other studies stated f BNPP is not influenced by water supplementation61. Although the mechanisms behind the allocation shift under drought are unclear, the decline tendency of f BNPP with increasing precipitation (Fig. 3c) supports the optimal partitioning theory and provides important constraints for the calibration and testing of dynamic carbon cycle models.

SWC has been proposed to be an important index in forecasting ecosystems’ responses to climate change62,63. The positive linear correlation between ANPP and SWC in 2016 suggests that SWC can better predict the variation in ANPP than precipitation amount. Comparing with precipitation amount, SWC are more responsible to ANPP changes, which can be attributed to the following two reasons. First, although growing season precipitation amount was recognized as a predictor of ANPP in grassland, soil moisture directly links to root activity, plant water status, and photosynthesis in physiology32,64. Other soil resource availability is also chronically altered through soil water dynamics65. Second, SWC was mediated by the water-storage capacity of the soil, which is better than precipitation to express water availability for plant growth66.

We also found that SIN explained 26.37% of the variation in ANPP across plots under different precipitation treatments (Fig. 5a). Because rainfall is the primary source of new nitrogen inputs to the system by net deposition and soil moisture also impacts soil nitrogen mineralization by changing the structure and function of soil microbial communities67, precipitation changes largely alter SIN dynamics. The reduced N availability under dry condition would constrain plant N uptake and growth, leading to lower productivity68,69. In addition, previous studies also indicated that total inorganic nitrogen is linearly related to natural annual precipitation70. Therefore, in the study site of alpine meadow where SIN limits plant production71, precipitation effects on ANPP are partly attributable to changes in SIN. The direct effects of soil water availability and the indirect effect through SIN in combination largely explained the ANPP variation across treatments. Our findings highlight SIN changes should be taken into consideration in understanding and modeling ANPP response to altered precipitation.

Beside the abiotic effects, biotic impacts of species composition also influence ANPP responses to precipitation change. As a major proportion of community (>67%), forbs biomass reduced significantly under extreme drought in this study, which led to an abrupt drop in ANPP (Fig. 2f). It was more sensitive to precipitation changes and more inhibited by extreme drought, because the growth of forbs usually requires more water than grasses72. Consequently, we predict that shifting species composition toward less sensitive species may dampen the response of ANPP to precipitation change.

Methods

Study site

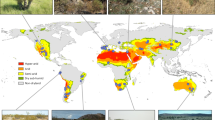

The study was conducted in an alpine meadow located in Hongyuan county (32°48′N, 102°33′E, 3500 m a.s.l.), which is in the eastern of Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. The mean annual temperature is 1.5 °C in the study site over the past 50 years. The average temperature of the hottest month (July) is 11.1 °C, and the mean of the coldest months (January) is −9.7 °C. The mean annual precipitation is 747 mm. The meadow community at our experimental site is dominated by grasses of Deschampsia caespitosa, Elymus nutans, and Agrostis hugoniana and forbs of Anemone rivularis, Potentilla anserina, and Polygonum viviparum. The soil of the study is classified as Mat Grygelic Cambisol according to Chinese Soil Taxonomy Research Group73, with mean bulk density is 0.89 g cm−3 .

Experimental design

The precipitation treatments have been conducted from May, 2015. It used a randomized complete block design with six levels of precipitation (1/12 P, 1/4 P, 1/2 P, 3/4 P, P and 5/4 P, P is the annual precipitation). Each treatment was replicated five times, and each replicate plot was 2 m × 1.5 m. The experiment consisted of thirty plots in six rows, with 2 m between the rows and between plots within a row (Fig. 6). We achieved the varying levels of precipitation using combinations of water catchments and rainout shelters. The rain-shelter was used to reduce precipitation as described by Yahdjian and Sala74, which is a fixed-location shelter with a roof consisting of curved bands of transparent acrylic that block different amounts of rainfall while minimally affecting other environment variables. Each shelter has a fixed metal structure (4 m in length, 3 m in width, 1.0–1.5 m in height). To minimize disturbance, we mechanically pushed fiberglass plats down to a depth of 40 cm in the soil surrounding the plots as in the Jasper Ridge Global Change Experiment75 to cut off lateral movement of soil water. The devices help achieve the goal of a free-air controlled experiment with minimal site disturbance. The 5/4 P treatment was made by adding water taken from the 3/4 P treatment. Under 3/4 P treatment, 1/4 P rainfall was accepted and removed from the plot. This gave us six precipitation levels without modifying the precipitation frequency and timing in our design.

Measuring variables

Rainfall, soil water content, temperature, and inorganic nitrogen concentration

The exact rainfall received by each plot was measured by rain gauge settled in the middle of each plot at the height of 20 cm. The precipitation amount was computed right after each rainfall event. Soil water content (SWC) and temperature (ST) in the top 10 cm were measured using a portable Time Domain Reflectometry equipment (TDR 100, Spectrum Technologies Inc., Chicago, USA) and sensors of LI-6400–09 (LI-COR Inc., Nebraska, USA), respectively, once a week over the growing season in both 2015 and 2016. Soil samples were collected at the end of the growing season, sieved through a 2 mm mesh. A subsample of 10 g of soil samples was extracted for measurement of inorganic nitrogen (NH4 + and NO3 −) in 50 mL 2 mol/L KCl on a rotary shaker for 1 h within 24 h. The filtrate made using filter paper was analyzed using the AA3 Continuous Flow Analyzer (AA3, SEAL Analytical GmbH, Germany).

ANPP, BGB, BNPP measurement and f BNPP estimation

ANPP was directly measured by clipping the sample strip (0.12 × 1.00 m) in each plot at peak biomass stage in each year (usually in the early of August). We separated the samples into different species, oven-dried at 65 °C for 48 h, and weighed. BNPP was measured by ingrowth core method34,76,77. Soil cores (diameter 9 cm) were taken from the same spot in each plot, with two soil layers (0–20 cm, 20–40 cm) at the peak biomass of vegetation in 2015. The holes were immediately filled with sieved root-free soil originating from the same depth outside of the plots that contained similar soil profile properties as the sampled ones. After one year, the soil cores of the same holes were taken with a soil auger of 7.5 cm diameter at the two layers. Different depths of soil cores were transferred into plastic bags and washed by filter (0.25 mm) under smoothly flowing water to obtain the root samples, oven-dried at 65 °C for 48 h, and weighed to the nearest 0.01 g. Belowground biomass (BGB) was measured using the roots of 2015, BNPP was estimated by the samples of 201630.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA was performed to analyze the differences of ANPP, BGB, BNPP and f BNPP among the treatments in each year. Stepwise multiple linear analyses and nonlinear regression analyses were used to evaluate the relationships of ANPP, BGB and BNPP with PPT, SWC, SIN and ST. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 19.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

References

Ciais, P. et al. Europe-wide reduction in primary productivity caused by the heat and drought in 2003. Nature 437, 529–533 (2005).

Hirabayashi, Y. et al. Global flood risk underclimate change. Nature Clim. Change 3, 816–821 (2013).

Woodhouse, C. A., Meko, D. M., MacDonald, G. M., Stahle, D. W. & Cook, E. R. A 1,200-year perspective of 21st century drought in southwestern North America. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 21283–21288 (2010).

Xiao, J. et al. Twentieth-Century Droughts and Their Impacts on Terrestrial Carbon Cycling in China. Earth Interactions 13, 1–31 (2009).

Young, D. J. N. et al. Long-term climate and competition explain forest mortality patterns under extreme drought. Ecology Letters 20, 78–86 (2017).

IPCC. Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation: special report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Dai, A. Increasing drought under global warming in observations and models. Nature Clim. Change 3, 52–58 (2013).

Knapp, A. K. & Smith, M. D. Variation Among Biomes in Temporal Dynamics of Aboveground Primary Production. Science 291, 481 (2001).

Fay, P. A., Kaufman, D. M., Nippert, J. B., Carlisle, J. D. & Harper, C. W. Changes in grassland ecosystem function due to extreme rainfall events: implications for responses to climate change. Glob Change Biol 14, 1600–1608 (2008).

Knapp, A. K. et al. Rainfall Variability, Carbon Cycling, and Plant Species Diversity in a Mesic Grassland. Science 298, 2202–2205 (2002).

Guo, Q. et al. Spatial variations in aboveground net primary productivity along a climate gradient in Eurasian temperate grassland: effects of mean annual precipitation and its seasonal distribution. Glob Change Biol 18, 3624–3631 (2012).

Zhou, X., Talley, M. & Luo, Y. Biomass, Litter, and Soil Respiration Along a Precipitation Gradient in Southern Great Plains, USA. Ecosystems 12, 1369–1380 (2009).

Yang, Y., Fang, J., Pan, Y. & Ji, C. Aboveground biomass in Tibetan grasslands. Journal of Arid Environments 73, 91–95 (2009).

Estiarte, M. et al. Few multiyear precipitation-reduction experiments find ashift in the productivity-precipitation relationship. Glob Change Biol 22, 2570–2581 (2016).

Yahdjian, L. & Sala, O. E. Vegetation structure constrains primary production response to water avalibility in the Patagonian steppe. Ecology 87, 952–962 (2006).

Knapp, A. K., Ciais, P. & Smith, M. D. Reconciling inconsistencies in precipitation–productivity relationships: implications for climate change. New Phytol 214, 41–47 (2017).

Deng, Q. et al. Effects of precipitation changes on aboveground net primary production and soil respiration in a switchgrass field. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 248, 29–37 (2017).

Wilcox, K. R. et al. Asymmetric responses of primary productivity to precipitation extremes: A synthesis of grassland precipitation manipulation experiments. Glob Change Biol 23, 4376–4385 (2017).

Luo, Y., Jiang, L., Niu, S. & Zhou, X. Nonlinear responses of land ecosystems to variation in precipitation. New Phytol 214, 5–7 (2017).

Milchunas, D. G. & Lauenroth, W. K. Belowground Primary Production by Carbon Isotope Decay and Long-term Root Biomass Dynamics. Ecosystems 4, 139–150 (2001).

Luo, Y., Sherry, R., Zhou, X. & Wan, S. Terrestrial carbon-cycle feedback to climate warming: experimental evidence on plant regulation and impacts of biofuel feedstock harvest. GCB Bioenergy 1, 62–74 (2009).

Scurlock, J. M. O., Johnson, K. & Olson, R. J. Estimating net primary productivity from grassland biomass dynamics measurements. Global Change Biology 8, 736–753 (2002).

Bai, Y. et al. Grazing alters ecosystem functioning and C:N:P stoichiometry of grasslands along a regional precipitation gradient. Journal of Applied Ecology 49, 1204–1215 (2012).

Zhou, X., Fei, S., Sherry, R. & Luo, Y. Root Biomass Dynamics Under Experimental Warming and Doubled Precipitation in a Tallgrass Prairie. Ecosystems 15, 542–554 (2012).

Bai, W. et al. Increased temperature and precipitation interact to affect root production, mortality, and turnover in a temperate steppe: implications for ecosystem C cycling. Glob Change Biol 16, 1306–1316 (2010).

Gao, Y. Z., Chen, Q., Lin, S., Giese, M. & Brueck, H. Resource manipulation effects on net primary production, biomass allocation and rain-use efficiency of two semiarid grassland sites in Inner Mongolia, China. Oecologia 165, 855–864 (2011).

Shipley, B. & Meziane, D. The balanced-growth hypothesis and the allometry of leaf and root biomass allocation. Functional Ecology 16, 326–331 (2002).

Titlyanova, A. A., Romanova, I. P., Kosykh, N. P. & Mironycheva-Tokareva, N. P. Pattern and process in above-ground and below-ground components of grassland ecosystems. Journal of Vegetation Science 10, 307–320 (1999).

Mokany, K., Raison, R. J. & Prokushkin, A. S. Critical analysis of root: shoot ratios in terrestrial biomes. Glob Change Biol 12, 84–96 (2006).

Hui, D. & Jackson, R. B. Geographical and interannual variability in biomass partitioning in grassland ecosystems: a synthesis of field data. New Phytol 169, 85–93 (2006).

Poorter, H. et al. Biomass allocation to leaves, stems and roots: meta-analyses of interspecific variation and environmental control. New Phytol 193, 30–50 (2012).

Fay, P. A., Carlisle, J. D., Knapp, A. K., Blair, J. M. & Collins, S. L. Productivity responses to altered rainfall patterns in a C4-dominated grassland. Oecologia 137, 245–251 (2003).

Niu, S., Sherry, R. A., Zhou, X., Wan, S. & Luo, Y. Nitrogen regulation of the climate–carbon feedback: evidence from a long-term global change experiment. Ecology 91, 3261–3273 (2010).

Xu, X. et al. Interannual variability in responses of belowground net primary productivity (NPP) and NPP partitioning to long-term warming and clipping in a tallgrass prairie. Glob Change Biol 18, 1648–1656 (2012).

Gu, C. & Riley, W. J. Combined effects of short term rainfall patterns and soil texture on soil nitrogen cycling — A modeling analysis. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 112, 141–154 (2010).

Aanderud, Z. T., Schoolmaster, D. R. & Lennon, J. T. Plants Mediate the Sensitivity of Soil Respiration to Rainfall Variability. Ecosystems 14, 156–167 (2011).

Zhang, X. et al. The impacts of precipitation increase and nitrogen addition on soil respiration in a semiarid temperate steppe. Ecosphere 8, e01655 (2017).

Burke, I. C., Lauenroth, W. K. & Parton, W. J. Regional and temporal variation in ner primary production and nitrogen mineralization in grasslands. Ecology 78, 1330–1340 (1997).

Mazzarino, M. J., Bertiller, M. B., Sain, C., Satti, P. & Coronato, F. Soil nitrogen dynamics in northeastern Patagonia steppe under different precipitation regimes. Plant and Soil 202, 125–131 (1998).

Kang, S. et al. Review of climate and cryospheric change in the Tibetan Plateau. Environmental Research Letters 5, 015101 (2010).

You, Q., Kang, S., Aguilar, E. & Yan, Y. Changes in daily climate extremes in the eastern and central Tibetan Plateau during 1961–2005. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 113, D07101 (2008).

Luo, T. et al. Leaf area index and net primary productivity along subtropical to alpine gradients in the Tibetan Plateau. Global Ecology and Biogeography 13, 345–358 (2004).

Yang, Y., Fang, J., Ji, C. & Han, W. Above- and belowground biomass allocation in Tibetan grasslands. Journal of Vegetation Science 20, 177–184 (2009).

Zhang, B. et al. Effects of rainfall amount and frequency on vegetation growth in a Tibetan alpine meadow. Climatic Change 118, 197–212 (2013).

Breshears, D. D. et al. Regional vegetation die-off in response to global-change-type drought. P Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 15144–15148 (2005).

Craine, J. M. et al. Timing of climate variability and grassland productivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, 3401–3405 (2012).

Hoover, D. L., Knapp, A. K. & Smith, M. D. Resistance and resilience of a grassland ecosystem to climate extremes. Ecology 95, 2646–2656 (2014).

Liu, L. et al. A cross-biome synthesis of soil respiration and its determinants under simulated precipitation changes. Glob Change Biol 22, 1394–1405 (2016).

Reddy, A. R., Chaitanya, K. V. & Vivekanandan, M. Drought-induced responses of photosynthesis and antioxidant metabolism in higher plants. Journal of Plant Physiology 161, 1189–1202 (2004).

Tian, L., Masson-Delmotte, V., Stievenard, M., Yao, T. & Jouzel, J. Tibetan Plateau summer monsoon northward extent revealed by measurements of water stable isotopes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 106, 28081–28088 (2001).

Huo, L. et al. Effect of Zoige alpine wetland degradation on the density and fractions of soil organic carbon. Ecological Engineering 51, 287–295 (2013).

Sala, O. E., Gherardi, L. A., Reichmann, L., Jobbágy, E. & Peters, D. Legacies of precipitation fluctuations on primary production: theory and data synthesis. Philos T R Soc B 367, 3135 (2012).

Enquist, B. J. & Niklas, K. J. Global Allocation Rules for Patterns of Biomass Partitioning in Seed Plants. Science 295, 1517–1520 (2002).

Evans, S. E. & Burke, I. C. Carbon and Nitrogen Decoupling Under an 11-Year Drought in the Shortgrass Steppe. Ecosystems 16, 20–33 (2013).

Kahmen, A., Perner, J. & Buchmann, N. Diversity-dependent productivity in semi-natural grasslands following climate perturbations. Functional Ecology 19, 594–601 (2005).

Fiala, K., Tůma, I. & Holub, P. Effect of Manipulated Rainfall on Root Production and Plant Belowground Dry Mass of Different Grassland Ecosystems. Ecosystems 12, 906–914 (2009).

Comeau, P. G. & Kimmins, J. P. Above-and below-ground biomass and production of lodgepole pine on sites with differing soil moisture regimes. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 19, 447–454 (1989).

Pietikäinen, J., Vaijärvi, E., Ilvesniemi, H., Fritze, H. & Westman, C. Carbon storage of microbes and roots and the flux of CO2 across a moisture gradient. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 29, 1197–1203 (1999).

Hayes, D. C. & Seastedt, T. R. Root dynamics of tallgrass prairie in wet and dry years. Canadian Journal of Botany 65, 787–791 (1987).

Yuan, Z. Y. & Chen, H. Y. H. Fine Root Biomass, Production, Turnover Rates, and Nutrient Contents in Boreal Forest Ecosystems in Relation to Species, Climate, Fertility, and Stand Age: Literature Review and Meta-Analyses. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 29, 204–221 (2010).

Gong, X. Y., Fanselow, N., Dittert, K., Taube, F. & Lin, S. Response of primary production and biomass allocation to nitrogen and water supplementation along a grazing intensity gradient in semiarid grassland. European Journal of Agronomy 63, 27–35 (2015).

Berdanier, A. B. & Klein, J. A. Growing Season Length and Soil Moisture Interactively Constrain High Elevation Aboveground Net Primary Production. Ecosystems 14, 963–974 (2011).

Sherry, R. A. et al. Lagged effects of experimental warming and doubled precipitation on annual and seasonal aboveground biomass production in a tallgrass prairie. Glob Change Biol 14, 2923–2936 (2008).

Nippert, J. B., Knapp, A. K. & Briggs, J. M. Intra-annual rainfall variability and grassland productivity: can the past predict the future? Plant Ecology 184, 65–74 (2006).

Knapp, A. K. et al. Consequences of More Extreme Precipitation Regimes for Terrestrial Ecosystems. BioScience 58, 811–821 (2008).

Eltahir, E. A. B. A Soil Moisture–Rainfall Feedback Mechanism: 1. Theory and observations. Water Resour Res 34, 765–776 (1998).

Fay, P. A., Carlisle, J. D., Knapp, A. K., Blair, J. M. & Collins, S. L. Altering Rainfall Timing and Quantity in a Mesic Grassland Ecosystem: Design and Performance of Rainfall Manipulation Shelters. Ecosystems 3, 308–319 (2000).

Landesman, W. J. & Dighton, J. Response of soil microbial communities and the production of plant-available nitrogen to a two-year rainfall manipulation in the New Jersey Pinelands. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 42, 1751–1758 (2010).

Wan, S., Hui, D., Wallace, L. & Luo, Y. Direct and indirect effects of experimental warming on ecosystem carbon processes in a tallgrass prairie. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 19, GB2014 (2005).

Austin, A. T. & Sala, O. E. Carbon and nitrogen dynamics across a natural precipitation gradient in Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vegetation Science 13, 351–360 (2002).

Liu, Y. et al. Plant and soil responses of an alpine steppe on the Tibetan Plateau to multi-level nitrogen addition. Plant and Soil 373, 515–529 (2013).

Knapp, A. K., Briggs, J. M. & Koelliker, J. K. Frequency and Extent of Water Limitation to Primary Production in a Mesic Temperate Grassland. Ecosystems 4, 19–28 (2001).

Group, C. S. T. R. Chinese soil taxonomy. Science, Beijing, 58–147 (1995).

Yahdjian, L. & Sala, O. E. A rainout shelter design for intercepting different amounts of rainfall. Oecologia 133, 95–101 (2002).

Zavaleta, E. S. et al. Grassland responses to three years of elevated temperature, CO2, precipitation, and N deposition. Ecological Monographs 73, 585–604 (2003).

Derner, J. D. & Briske, D. D. Does a tradeoff exist between morphological and physiological root plasticity? A comparison of grass growth forms. Acta Oecologica 20, 519–526 (1999).

Gao, Y. Z. et al. Belowground net primary productivity and biomass allocation of a grassland in Inner Mongolia is affected by grazing intensity. Plant and Soil 307, 41–50 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of Institute of Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau in Southwest University for Nationalities. This work was financially supported by the National Science Foundation of China (31470528, 31625006), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2016YFC0501803), and the “Thousand Youth Talents Plan” program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.N. and J.S. conceived and designed the experiments. F.Z., Q.Q. and B.S. performed the experiments. F.Z. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. Y.C. and Q.Z. revised the manuscript and conducted the measurements. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, F., Quan, Q., Song, B. et al. Net primary productivity and its partitioning in response to precipitation gradient in an alpine meadow. Sci Rep 7, 15193 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15580-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15580-6

This article is cited by

-

Species Diversity and Stability of Dominant Species Dominate the Stability of Community Biomass in an Alpine Meadow Under Variable Precipitation

Ecosystems (2023)

-

Simulating warmer and drier climate increases root production but decreases root decomposition in an alpine grassland on the Tibetan plateau

Plant and Soil (2021)

-

Asymmetric responses of plant community structure and composition to precipitation variabilities in a semi-arid steppe

Oecologia (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.