Abstract

We analysed suppressive effects of potassium (K) fertilisation on radiocesium (137Cs) uptake by hinoki cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa) seedlings from soils contaminated after the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. Three-year-old seedlings were planted in a clear-cut forest (ca. 4 ha) during June–July 2014, and potassium chloride fertiliser (83 kg K ha−1) was applied twice (August 2014 and April 2015). 137Cs concentrations in the needles in the fertilised plots were one-eighth of those in the control (unfertilised) plots at the end of the second growing season (October 2015). Our results clearly indicated that K fertilisation reduced radiocesium transfer from soil to planted cypress seedlings. A linear mixed model analysis revealed that 137Cs concentrations in the needles were significantly affected by 137Cs inventory in the soil (Bq m−2) adjacent to the sampled seedlings, exchangeable K concentrations in surface mineral soils (0–5 cm) and fertilisation. The exchangeable K concentrations in surface soils in October 2015 did not differ from those in August 2014 (before fertilisation) in the fertilised plots and in the control plots. These results suggested that the levels of exchangeable K would temporarily increase by fertilisation during the growing season, and radiocesium uptake by tree roots was suppressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

After the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (FDNPP) accident following the large earthquake on 11 March 2011, large areas of forest lands, as well as other lands, were contaminated with the released radionuclides around the coastal and central areas of Fukushima prefecture. Among the radionuclides, cesium-137 (137Cs), one of the most released radionuclides, has a long half-life (about 30.2 years). Although 137Cs outflow flux from the forests was small1, 137Cs is considered to circulate within the forests2, and prolonged contamination of the forests is a great concern in this region. Several studies have been conducted for understanding the dynamics of radiocesium within the contaminated forests after the accident3,4,5. However, the transfer of radiocesium to the trees planted by afforestation after the accident has not been well studied, despite such information being indispensable to discuss future availability of wood and forest resources.

Radiocesium transfer to trees has been evaluated by the aggregated transfer factor (T ag, m2 kg−1)6, which is a ratio of radionuclide activity (Bq kg−1) of living organisms or their compartments to the radionuclide inventory per ground area (Bq m−2). The T ag of tree compartments is defined by the following equation (1):

The T ag is used for natural or semi-natural environments, including forests, since vertical and horizontal distribution of radionuclides is highly heterogeneous in such environments. In this study, we define the total soil 137Cs inventory as sum of 137Cs inventory of organic layer and that of mineral soil from 0 cm to 20 cm depth.

Such T ag concept intends that the radiocesium transfer to trees would be usually controlled by radiocesium absorption from soils via roots. However, recent studies have shown that not only root absorption but also foliar uptake and translocation of radiocesium deposited on the leaf surface might play an important role in the initial contamination of the internal parts of trees7,8,9. In addition, the initially contaminated radiocesium in woods would remain within the trees for a long time10. Therefore, to reduce radiocesium levels of forest trees in the contaminated area, it would be effective to grow newly planted trees with no initial contamination, and understanding the radiocesium dynamics in such planted trees is also necessary for future forestry in the contaminated areas.

The transfer of radiocesium via roots is affected by soil environmental conditions and tree species11. In particular, potassium (K) present in the soil is considered as a key factor, because cesium is an alkali metal, and K and the K transporters in plant roots could probably affect the uptake of cesium, especially under low external K concentrations12. Furthermore, it has been reported that K fertilisation in paddy fields and farmlands reduced radiocesium transfer to rice and other crop plants growing on the soil contaminated by the FDNPP accident13,14.

In the case of trees, some reports show that K fertilisation reduced the radiocesium activity of trees (pine) after the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant (ChNPP) accident in 198615,16. However, to our knowledge, no study has reported about the effects of K fertilisation on the radiocesium activity of forest trees after the FDNPP accident.

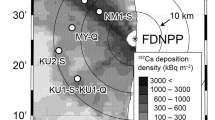

In this study, to understand the behaviour of radiocesium among the afforested areas and develop the technique for decreasing radiocesium transfer to trees, a mixed forest of pine and deciduous broad-leaved trees in the Kawauchi village 26 km apart from the FDNPP was clearly cut, and the seedlings of Japanese cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa), which is one of the major conifer species, were planted (Fig. 1). Japanese cypress prefers temperate climate, and it is largely planted (one-third of Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica), the most dominant tree species, as area) in the relatively warm coastal area surrounding the FDNPP, while it is rarely cultivated on the inland of Fukushima prefecture17. The research site has infertile soils and it is adequate to Japanese cypress than cedar.

The location of the study site. The study site is located at the south side of Kawauchi village and 26 km away from the FDNPP. The two circles indicate 20 and 40 km from the FDNPP, respectively. The 137Cs deposition data were obtained from the airborne monitoring survey by prefectures (decay corrected on 31 May 2012)36. The municipal boundaries were generated from Administrative Zones Data37. The map was created using R version 3.4.031 and ggplot2 package38.

To elucidate the prolonged effects of K fertilisation on the uptake of soil radiocesium, eight plots measuring 0.225–0.25 hectare (ha) were established in the site (Fig. 2) and 83 kg K ha−1 was applied on half of the plots twice in August 2014 and April 2015 (total 166 kg K ha−1). In each plot, five seedlings and nearby soils were sampled, and the random effect of the plot was considered in the analysis. We demonstrate and discuss the results of the first 2 years of K fertilisation experiment conducted in a stand contaminated by the FDNPP accident and planted with C. obtusa seedlings without initial radiocesium contamination.

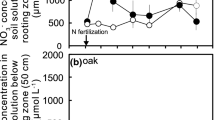

The map of the study site. Eight plots involving four K-fertilised plots (K1–4) and four control plots (C1–4) were established. Plot size was 50 × 50 m, except for K4 (45 × 50 m) and C4 (40 × 60 m). The spatial distribution of air dose rate at 1-m height was visualised by contour lines (blue colour, 0.1 µSv h−1 intervals) and colour gradient within plots (measured in Augst 2014). Black points: 10-m grid within plots, Red dot lines: boundaries of 30 × 30 m quadrat for sampling, Dark green lines: contour lines indicating 10-m elevation, Light green lines: contour lines indicating 2-m elevation. The contour lines of elevation were generated from 5-m-resolution DEM39.

Results

Physicochemical properties of soils

The physicochemical properties of surface (0–5 cm) and deeper (5–10 and 10–20 cm) soil layers just before fertilisation in August 2014 and the surface soil layers in October 2015 were recorded (Table 1). No significant differences in the soil physicochemical properties were observed between the C- and K-plots (nested ANOVA, p > 0.05). In addition, the exchangeable K concentrations in surface soils in October 2015 (after fertilisation) did not differ from those obtained in August 2014 (before fertilisation). A linear mixed model (LMM) analysis was conducted for August 2014 samples using the soil exchangeable K concentrations as a response variable, the weight of organic layer as an explanatory variable and the sampling plot as a random effect. In the analysis, the regression coefficient was positively significant (p = 0.009).

137Cs concentrations in seedlings

Initial 137Cs concentrations in the Japanese cypress (C. obtusa) seedlings (pre-planting) were 4.81 ± 2.44 Bq kg−1 in needles, <4.89 Bq kg−1 in stems (all samples had less than the detection limit) and 20.6 ± 17.6 Bq kg−1 in roots (Fig. 3). The 137Cs concentrations in the seedlings harvested after the first growing season (November 2014 and April 2015, 1st year) were higher than those in the pre-planted seedlings (August 2014), and the roots sampled from control (C-) plots had significantly higher 137Cs concentrations than those from the K-fertilised (K-) plots (nested analysis of variance (ANOVA), p < 0.05). On the other hand, there were no significant differences between treatments in the needles and stems after the first growing season. 137Cs concentrations in the seedlings sampled in October 2015 (2nd year) were significantly different between the C- and K-plots (Fig. 3), wherein the 137Cs concentrations in the seedlings from C-plots were higher (300–550 Bq kg−1 in average) than those in the seedlings sampled in the previous year (<100 Bq kg−1 in average), whereas the increment in K-plots was less evident. The T ag value showed a similar trend as that of 137Cs concentrations (Fig. 4). The values after the first growing season or the values in the K-plots were usually <0.0025 m2 kg−1, whereas the seedlings from the C-plots showed T ag > 0.01 m2 kg−1 after the second growing season. 137Cs concentrations in each compartment of the seedlings increased with increasing 137Cs inventory of soil and were decreased by K treatment (Supplementary Fig. S1).

137Cs concentrations in the cypress seedlings sampled at control plots (open bar) and K-fertilised plots (grey bar). Asterisks (*) indicate that samples obtained at the same time showed significant differences between treatments (nested ANOVA, p < 0.05). All stem samples at pre-planting showed less values than the detection limit despite long (24-h) measurements. Subsequently, the mean of detection limits was shown.

137Cs concentrations in the needles and roots sampled in October 2015 showed positive correlations (Fig. 5). However, there was an interaction between root 137Cs concentration and fertilisation (nested analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), p < 0.05), and the slope parameter of root 137Cs concentration decreased in the K-plots compared to that in the C-plots. The ratio of 137Cs activity of needles to that of roots was 1.66 ± 0.51 in C-plots and 1.29 ± 0.96 in K-plots (n = 20).

Relationship between 137Cs concentrations among compartments (needles and roots) in control (open symbols) and K-fertilised (grey symbols). Both axes are shown by logarithmic scales. The seedlings were sampled in October 2015 at the end of the second growing season. Two linear regression lines were drawn for control (solid line) and K-fertilised (dotted line) because a significant interaction between logarithmic root 137Cs concentration and fertilisation treatment was observed in the regression analysis (nested ANCOVA, p < 0.05).

The online Supplementary Table S1 shows the height, the diameter of the ground surface and the weight of the compartments. The average height of the seedlings was about 50 cm while planting in August 2014 and increased by about 2 cm in November 2014, the end of the growing season. The tree height increased to more than 70 cm in average in the next autumn. The needles, stems and roots of the seedlings sampled for radioactive analysis in August 2014 weighed 14.3 ± 4.2, 11.2 ± 3.2 and 10.6 ± 3.2 g, respectively (mean ± SD, n = 20). Thereafter, the needle weights decreased and the root weights increased in the first autumn. The sample weights of all compartments increased in October 2015 as follows: 36–41 g for needles, 30–32 g for stems and 18 g for roots. No differences in both tree heights and sample weights were observed among the plot treatments.

The online Supplementary Table S2 shows the nutrient concentrations of cypress needles sampled for measurement of radiocesium concentration in autumn 2015. The needle potassium concentration in K-plots was significantly higher than that in C-plots, but, to the contrary, the concentrations of magnesium, calcium and manganese were significantly lower in K-plots than those in C-plots (nested ANOVA, p < 0.05).

Relationship between 137Cs activity of seedlings and soil properties

The relationship between T ag of needles and surface soil concentrations of exchangeable K is shown in Fig. 6. In the C-plots, some seedlings with exchangeable K concentrations < 0.50 cmol (+) kg−1 had T ag values > 0.002 m2 kg−1. The T ag values of all seedlings in K-plots were < 0.001 m2 kg−1 and obviously smaller than those of the seedlings in C-plots regardless of the soil exchangeable K concentration.

The results of a LMM analysis for cypress needles sampled in autumn 2015 are shown in Table 2. The variation in 137Cs concentrations in the needles (Cs needle) can be explained by the following equation:

where logarithmic soil 137Cs inventory (Cs soil_inv), K fertilisation (K) and logarithmic exchangeable K concentrations in surface soil (exK) are significant variables for fixed effects (p < 0.05). The variable of random effect of sampling plots (re) was 0.11. In general, since soil exchangeable K concentrations would be directly affected by K fertilisation, using both exchangeable K and fertilisation as explanatory variables is believed to be not preferable. However, the soil exchangeable K concentration was not changed before and after fertilisation (Table 2). Therefore, we used both factors in the analysis, in which effects of the exK in the equations were likely to result from spatial variation of soil exchangeable K concentrations (Fig. 6). The Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) of the above model shown by equation (2) was 96.4. The model using logarithmic cation exchange capacity (CEC) as the explanatory variable instead of soil 137Cs inventory in the previous model (equation (2)) showed the minimum AIC (AIC = 90.9).

Although the carbon contents positively correlated with CEC (R = 0.89, p < 0.001), the carbon contents were not used in the LMM analysis because of lack of analysis due to small sample amount (n = 25). The models involving other factors such as other soil physicochemical properties, size of the sampled seedlings and slope angle of the sampling site showed no or slight decrease (ΔAIC < 0.3) compared with the former two models.

Discussion

This study aimed to elucidate the effects of K fertilisation on radiocesium transfer from soil to trees planted after the FDNPP accident in 2011. We planted Japanese cypress seedlings in a clear-cut forest in Fukushima prefecture in early summer 2014, and K fertiliser was applied twice (in August 2014 and in April 2015) (166 kg ha−1 K in total) in the K-fertilised plots. Seedlings harvested after the first growing season (autumn 2014 and spring 2015) did not show a difference in 137Cs concentrations between K-fertilised and control plots (K- and C- plots, respectively), except in roots. During the second growing season, however, 137Cs concentrations in the seedlings from the C-plots were much increased than these from the K-plots. Consequently, 137Cs concentrations in the seedlings from the K-plots were one-eighth of those in the seedlings from the C-plots (Fig. 3). The T ag value also showed similar patterns of variation in 137Cs concentrations in the plant samples (Fig. 4). After the FDNPP accident, the suppressive effects of K fertilisation on the uptake of radiocesium by crops have been reported by several papers13,14,18,19, but, to our knowledge, no study has been conducted for field-grown tree species. Thus, this is the first study clearly showing the suppressive effects of K fertilisation on radiocesium uptake by trees growing on the soil contaminated by the FDNPP accident. In the first growing season, the root slightly grew probably for root-taking, whereas there was no growth in the needles and stems (Supplementary Table S1). At the same time, there was no difference in 137Cs concentrations in the needles and stems between the K- and C-plots. This is probably because the uptake of radiocesium occurred with growth.

Several previous studies have suggested that K fertilisation suppressed radiocesium absorption by pine trees15, shrubs and mushrooms20 in mature stands contaminated by the ChNPP accident. Those results showed that 137Cs concentrations in plants and fungi in K-fertilised sites decreased by a maximum of ca. 60% compared with those in unfertilised sites. Our experiments, on the other hand, demonstrated higher suppressive effects of K fertilisation (by 88% decrease in Cs uptake) than those reported previously. This is probably because we fertilised small seedlings intensively in a short period (i.e. twice with 83 kg ha−1 of K in 2 years) immediately after the planting, whereas the previous studies investigated mature stands that were fertilised only once after the accident or fertilised several times, but less intensively, since 1960s. Those studies also demonstrated that the effects of fertilisations, including those before the accident, lasted for more than 10 years, although the K fertilisations after the accident reduced the 137Cs levels in the plants more obviously. In contrast, radiocesium deposited on the crowns of standing trees was immediately taken up via the surface of leaves and/or branches at the initial stage of the deposition (direct contamination)7,9 and would remain in the trees for a long time10. Taken together, the results of our study suggested that K fertilisation can be more effective to newly planted seedlings than to larger trees that received the direct above-ground deposition for decreasing the levels of radiocesium contamination.

For seedling samples harvested in autumn 2015, a positive correlation was observed in 137Cs concentrations between needles and roots (Fig. 5). These results showed that K fertilisation inhibited root uptake of radiocesium and consequently suppressed the increase in needle 137Cs concentrations. K fertilisation has been shown to affect not only root uptake of radiocesium but also translocation to other plant parts in rice18. In our analysis, the slope was significantly lower in K-plots than that in C-plots, suggesting that the fertilisation might also inhibit radiocesium translocation from the root to needles of cypress seedlings.

In autumn 2015, the physicochemical properties of surface mineral soils, including exchangeable K concentrations, were surveyed, and the relationship between T ag values and exchangeable K concentrations seemed to show an inverse variation in C-plots, and all samples with T ag values >0.002 m2 kg−1 in the needles of the C-plots were from locations with soil exchangeable K concentrations <0.50 cmol (+) kg−1. The relationships between the soil–plant radiocesium transfer and soil exchangeable K concentrations were also studied in a paddy field contaminated by the FDNPP accident. These studies suggested that the threshold level of soil exchangeable K concentrations was 25 mg K2O per 100 g of soil for reducing the radiocesium uptake by rice14,21. This value is equal to 0.53 cmol (+) K kg−1, which was similar to the threshold soil K concentration observed in our cypress stand (Fig. 6), despite the large differences in soil conditions between the forest soil and submerged paddy soil. Moreover, our results clearly showed that K fertilisation effectively reduced the radiocesium transfer in the case of such a low exchangeable K condition.

We initially hypothesised that increased soil exchangeable K concentrations due to fertilisation would suppress radiocesium root uptake by cypress seedlings in the fertilised plots. The soil exchangeable K concentrations, however, were unchanged by fertilisation, in contrast to our expectations (Table 1). Moreover, T ag values of needles in the K-plots were much lower than those of needles in the C-plots even when the soil exchangeable K concentrations were <0.50 cmol (+) kg−1 (Table 2 and Fig. 6). Since the analysed soil samples were collected at the end of the growing season in this study, these low levels of soil exchangeable K concentrations in the fertilised plots probably resulted from K uptake by the cypress seedlings in the growing season, as has been reported for peach trees that absorbed and accumulated K in summer22. Actually, because the fertilised seedlings showed increased K concentrations in the needles (Supplementary Table S2), it was concluded that these seedlings absorbed fertilised K from the soil. Moreover, the soluble K can easily penetrate into deeper layers of the soil, which would decrease the K concentrations in the surface soil23. Therefore, it was suggested that the levels of exchangeable K would temporarily increase by fertilisation during the growing season, and radiocesium uptake by tree roots was suppressed. An LMM analysis indicated that the soil exchangeable K concentrations in the surface soils linearly increased with the increasing amount of organic layer in August 2014, just after the planting. Since tree composition and the rate of litter decomposition are expected to be constant among the plots, the amount of organic layer amount might reflect the ability of K supply. In future studies, it would be better to examine exchangeable K concentrations in the soil at the beginning of the growing season after the fertilisation for analysing the relationships between soil–plant radiocesium transfer and exchangeable K concentrations in the soil.

Another LMM analysis for estimating the needle 137Cs concentration indicated that the coefficients of soil 137Cs inventories, fertilisation treatment and surface soil exchangeable K concentrations were significant (Table 2). These results suggested that such parameters could be factors determining the amount of radiocesium absorption. In particular, in the model, the coefficient of logarithmic 137Cs inventories was nearly one (equation (3)). This result indicated that the relationship of radiocesium between needles and soils was linear, but not exponential. If the coefficient of 137Cs inventories in equation (2) was fixed as one, the equation was transformed to the equation of T ag as follows:

This equation shows that the T ag values were affected by soil exchangeable K and fertilisation as visualised in Fig. 6.

On the other hand, the model that used CEC as an explanatory variable instead of 137Cs inventories was selected as the best model because of its minimum AIC (Table 2). Although it is difficult to conclude the mechanism from these results, since CEC showed a positive correlation with the soil carbon content, it was possible that the soil anion site derived from the organic matter might hold radiocesium cation and supply it to trees. Such a hypothesis coincided with the results that organic anion has weak adhesion capacity of cesium and suppresses the cesium adhesion to clay minerals24. Further research resolving the factor of radiocesium transfer from soils to trees is necessary to promote the suppression of radiocesium transfer.

We demonstrated that K fertilisation could suppress the radiocesium root uptake by planted cypress seedlings in a forest highly contaminated with radiocesium due to the FDNPP accident. Previous reports had indicated that the suppressive effects of K fertilisation on the soil–plant radiocesium transfer varied with the amounts and frequency of fertilisation and the soil conditions receiving the fertilisation15,25. On the other hand, we may need to monitor the adverse effects of fertilisation on tree growth. The fertilised needles showed significantly decreased Mg, Ca and Mn concentrations than those of unfertilised needles, but their K concentrations were increased. These results clearly indicated that K fertilisation altered the nutritional balance of seedlings. In our cypress stand, the total amount of exchangeable K concentrations in mineral soil (0–20 cm depth) was 10.4 g m−2, which is comparable to the amount of fertilisation (8.3 g m−2) in this study. Although the amount of fertilisation appears not to be excessive, repeated fertilisation may cause lack of other cations in the soil or nutritional imbalances and consequently may exert harmful effects on tree growth. Therefore, an important issue for future studies would be providing information on amounts and frequency of the K fertilisation that can be effective for long periods needed for wood production without adverse effects on tree growth. We expect that long-term monitoring of the cypress stand used in this study will deepen our insights into soil–tree radiocesium transfer, which in turn, would help to establish practical techniques for wood production in the area with radiocesium deposition.

Materials and Methods

Site

This study was conducted in Mariyama area of Kawauchi village in Fukushima prefecture (37°16′ N, 140°49′ E, Fig. 1), which is 26 km away to the southwest from the FDNPP. This study site belongs to the Abukuma mountainous area, and its altitude is 680 m, where the mean annual temperature and precipitation were 10.3 °C and 1465 mm (data obtained at Kawauchi monitoring station of AMeDAS, Japan Meteorological Agency, 37°20′ N, 140°49′ E), respectively. The study site has a complex micro-topographical conditions, including a stream and a ridge, where slopes range from 0 to 36 degrees with varied aspects (Fig. 2). The 137Cs deposition in the studied area was estimated to be 380–400 kBq m−2 by the fourth airborne monitoring conducted from October 25 to November 5 in 201126.

The study site had been a mixed forest of Japanese red pine (Pinus densiflora) and deciduous broad-leaved trees such as oak (Quercus serrata and Q. mongolica var. crispula). The soil is classified as brown forest soil27, in which the parent material is granite affected by volcanic ash on the surface. The soil texture is light clay (LiC) containing 280 g kg−1 of clay, and vermiculite is dominant with clay minerals. These mineral soil properties are common in the Abukuma mountainous area. The trees in the 4-ha study site were clear-cut during winter to spring in 2014, and all the logs and branches were stacked in the site along the contour.

Three-year-old seedlings of Japanese cypress (C. obtusa), which were grown at a nursery in Minami-Soma (ca. 44 km north east from the study site), were planted at a density of about 2,800 plants per hectare during June to July in 2014. Before planting, 20 seedlings were sampled and their heights, diameters at the ground surface and weights of the needles, stems and roots were measured. Moreover, the initial radiocesium levels were determined in 5 of the 20 seedlings. The dwarf bamboo growing on the ground surface was periodically mowed.

Plot set-up, fertilisation and monitoring

In July 2014, eight plots were established (Fig. 2) in the study site, six of them were 0.25 ha (50 × 50 m) and the other two plots were 0.225 ha (45 × 50 m) and 0.24 ha (40 × 60 m), respectively, due to the location of the work road and the micro-topographical conditions of the stand. Furthermore, a 0.09-ha quadrat (30 × 30 m) was set up in each plot for sampling for radionuclide analysis. Among those eight plots, four were applied with K fertiliser, and the other four plots were used as unfertilised control plots (Fig. 2). In November 2014 and October 2015, the heights and diameters at the ground surface of seedlings growing in the eight quadrats were measured.

K fertilisation was conducted in August 2014 and April 2015, in each of which potassium chloride fertiliser (60% KCl) was applied at the rate of 83 kg K per hectare (ha). Thus, the total amount of K fertilisation was 166 kg K ha−1.

In August 2014, the air dose rate at 1-m and 5-cm height was measured above the 10-m grids in all the eight plots (50 × 50 m, etc.) using dual plastic scintillators equipped with a GPS system (Gamma plotter H, Japan Atomic Energy Agency).

Samplings

Accumulated organic matters on the ground and mineral soils were sampled at five points in each quadrat just before the first fertilisation in August 2014. To collect the organic matter samples, a square frame with an area of 0.625 m2 (25 × 25 cm) was set on the ground at each sampling location, and the organic matters in the frame were manually collected28. In one of those five sampling locations, mineral soil samples were collected using a 475-mL core sampler (φ11 cm, 5 cm height, DIK-1815-11, Daiki Rika Kogyo Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) from the soil layers at 0–5, 5–10, 10–15 and 15–20 cm depths28. In the remaining four sampling locations, mineral soils were manually sampled using small shovels at 0–5, 5–10 and 10–20 cm depth layers.

In November 2014, a seedling was harvested in each quadrat by pulling up a whole plant, including the roots, using a shovel. At the same time, organic matter and mineral soil samples close to the seedling (within 50 cm) were also collected. In April 2015, just before the second fertilisation, four sets of the samples were additionally collected in each quadrat. These five sets of samples (seedlings, organic matter and mineral soil) were considered as samples after one growing season in the K fertilisation experiment, because April is the end of the dormant season (before the second growing season) in this study site. In those samplings, organic matter was collected in the same way as initial sampling in August 2014, whereas soil samples below the organic layers were collected as soil cores with 0–20 cm soil depth and 5-cm diameter using a soil auger (HS-25S, Fujiwara Scientific Company, Tokyo, Japan). The 20-cm soil cores were divided into four pieces with 5-cm depth intervals in the laboratory.

In October 2015, five seedlings and nearby soils were sampled in each quadrat. The sampling was carried out in the same way as done in November 2014 and April 2015.

Sample preparation and analyses

The plant and soil samples were transported to the laboratory and subjected to the following sample preparation and measurements. The seedlings were divided into needles, stems (with branches) and roots using scissors and were washed with tap water and subsequently with deionised water. The washed needles, stems, roots and the accumulated organic matters were dried at 75 °C for > 48 h and weighed. Thereafter, the dried samples were milled and packed into 100-mL plastic containers (U8 case) for measuring the radioactivity. The mineral soils were air-dried at room temperature for more than 2 weeks. These soil core samples were weighed to determine the bulk density of the soil. The bulk densities of the soil core samples collected in August 2014 were used as substitutes for those of manually sampled soils in the same plots. The air-dried soil samples were sieved through a 2-mm mesh, and the fine soils were packed into the 100-mL plastic containers (U8 case).

The sample activity of 134Cs and 137Cs (Bq kg−1) was measured using an HPGe coaxial detector system (GEM20-70, Seiko EG&G, Tokyo, Japan) at FFPRI. The measurement time was 3600–86400 s until the standard errors became <10% of the measured activity. If the measurement activity was below the detection limit despite measurement for a long time, the detection limit was used for statistical analysis as described later. The measurement of radioactivity has been described in detail by Komatsu et al. (2016)3 and Kuroda et al. (2013)29. The radiocesium activity of some samples was measured at the Kankyo Research Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). The 137Cs inventories (Bq m−2) in the organic layer and the mineral soil layers were calculated using 137Cs concentrations (Bq kg−1) and dry masses of organic layers per unit area or bulk density of the mineral soils (kg m−2). T ag of each compartment was calculated from equation (1).

Elemental analysis was conducted for the needles sampled for radiocesium analysis in the second growing season. The concentrations of Na, Mg, Al, P, K, Ca, Mn, Fe and Zn in the needle samples were measured after wet digestion by HNO3 and H2O2 (4:1) using ICP-MS (Agilent 7700x, Agilent Technologies). Among the mineral soil samples, the physicochemical properties of 40 (five replicates in one quadrat) soil samples at the surface layer (0–5 cm) and 16 (one replicate) soils in the deeper layers (5–10 and 10–20 cm) in August 2014 and 40 surface soils in October 2015 were analysed. For the physicochemical analyses, sieved fine soils were used, and core samples of 10–15 and 15–20 cm were mixed. Soil pH (H2O) was measured by a glass-electrode method, in which the soil:liquid ratio was 1:2.5. Exchangeable cations (Ca, Mg, K, Na and 133Cs) in the soil samples were extracted with 1 mol L−1 ammonium acetate solution at pH 7. The concentrations of exchangeable cations were determined using ICP-MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific iCap Q). Cation exchange capacity (CEC) was analysed according to Schollenberger method30, in which the soil samples were shaken with 1 mol L−1 ammonium acetate solution at pH 7 and then with 10% NaCl; following Kjeldahl distillation, the ammonium ion content of the solution was then determined by titration with NaOH. Total carbon and nitrogen levels in the soils were analysed by dry combustion method.

Statistical analysis

Samples were collected by nested design (five replicates from eight plots). To assess the factors affecting the log-transformed 137Cs concentrations in the seedlings sampled in autumn 2015, an LMM analysis was performed involving sampling plots serving as a random effect. In this analysis, plot treatment (with fertiliser or not), log-transformed total soil 137Cs inventory, physicochemical properties of 0–5 cm soil, plant size parameters (height, diameter and weights) and slope angle of the sampling site were used as candidate explanatory variables. The best model was selected based on stepwise AIC method. In the LMM analysis, maximum likelihood estimation was used for estimating model parameters. For evaluating the effect of fertiliser on the soil physicochemical properties and/or radiocesium concentrations in the seedlings sampled at the same time, a nested ANOVA was conducted with sampling plots serving as a random effect. These statistical analyses were performed by R version 3.4.031, and LMM analysis was done by R packages of lme432 and lmerTest33. The mean and standard deviation values, including the censored data, were obtained by maximum likelihood estimation34 using R packages of NADA35.

References

Shinomiya, Y. et al. Radioactive cesium discharge in stream water from a small watershed in forested headwaters during a typhoon flood event. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 60, 765–771 (2014).

Hashimoto, S. et al. Predicted spatio-temporal dynamics of radiocesium deposited onto forests following the Fukushima nuclear accident. Sci. Rep. 3, 2564, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02564 (2013).

Komatsu, M. et al. Characteristics of initial deposition and behavior of radiocesium in forest ecosystems of different locations and species affected by the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. J. Environ. Radioact. 161, 2–10 (2016).

Ohte, N. et al. Ecosystem monitoring of radiocesium redistribution dynamics in a forested catchment in Fukushima after the Nuclear Power Plant accident in March 2011 in Agricultural Implications of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident (eds Nakanishi, T. M. & Tanoi, K.)175–188 (Springer Japan, 2016).

Coppin, F. et al. Radiocaesium partitioning in Japanese cedar forests following the ‘early’ phase of Fukushima fallout redistribution. Sci. Rep. 6, 37618, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37618 (2016).

International Atomic Energy Agency. Handbook of Parameter Values for the Prediction of Radionuclide Transfer in Terrestrial and Freshwater Environments. (International Atomic Energy Agency, 2010).

Thiry, Y., Garcia-Sanchez, L. & Hurtevent, P. Experimental quantification of radiocesium recycling in a coniferous tree after aerial contamination: Field loss dynamics, translocation and final partitioning. J. Environ. Radioact. 161, 1–9 (2016).

Masumori, M., Nogawa, N., Sugiura, S. & Tange, T. Radiocesium in stem, branch and leaf of Cryptomeria japonica and Pinus densiflora trees: cases of forests in Minamisoma in 2012 and 2013 (in Japanese with English summary). J. Japanese For. Soc. 97, 51–56 (2014).

Nishikiori, T. et al. Uptake and translocation of radiocesium in cedar leaves following the Fukushima nuclear accident. Sci. Total Environ. 502, 611–616 (2015).

Thiry, Y., Goor, F. & Riesen, T. The true distribution and accumulation of radiocaesium in stem of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.). J. Environ. Radioact. 58, 243–259 (2002).

Calmon, P., Thiry, Y., Zibold, G., Rantavaara, A. & Fesenko, S. Transfer parameter values in temperate forest ecosystems: a review. J. Environ. Radioact. 100, 757–766 (2009).

Zhu, Y.-G. & Smolders, E. Plant uptake of radiocaesium: a review of mechanisms, regulation and application. J. Exp. Bot. 51, 1635–1645 (2000).

Ohmori, Y. et al. The effect of fertilization on cesium concentration of rice grown in a paddy field in Fukushima Prefecture in 2011 and 2012. J. Plant Res. 127, 67–71 (2014).

Kato, N. et al. Potassium fertilizer and other materials as countermeasures to reduce radiocesium levels in rice: Results of urgent experiments in 2011 responding to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 61, 179–190 (2015).

Kaunisto, S., Aro, L. & Rantavaara, A. Effect of fertilisation on the potassium and radiocaesium distribution in tree stands (Pinus sylvestris L.) and peat on a pine mire. Environ. Pollut. 117, 111–119 (2002).

Aro, L. & Rantavaara, A. Long-term effect of fertilization on 137Cs concentration in Scots pine needles. Radioprotection 46, 479–482 (2011).

Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Fukushima Prefecture. Statistics of forest and forestry in Fukushima Prefecture (in Japanese). https://www.pref.fukushima.lg.jp/uploaded/attachment/55727.pdf (2011).

Nobori, T., Kobayashi, N. I., Tanoi, K. & Nakanishi, T. M. Effects of potassium in reducing the radiocesium translocation to grain in rice. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 60, 772–781 (2014).

Saito, T. et al. Effect of application timing of potassium fertilizer on root uptake of 137Cs in brown rice. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 303, 1585–1587 (2015).

Rosén, K., Vinichuk, M., Nikolova, I. & Johanson, K. Long-term effects of single potassium fertilization on 137Cs levels in plants and fungi in a boreal forest ecosystem. J. Environ. Radioact. 102, 178–184 (2011).

National Agriculture and Food Research Organization. Potassium fertilization for reducing radiocesium uptake of brown rice (in Japanese). http://www.naro.affrc.go.jp/publicity_report/press/laboratory/narc/027913.html (2012).

Stassen, P. J. C. & Stadler, J. D. Seasonal uptake of phosphorus, potassium, calcium and magnesium by young peach trees. South African J. Plant Soil 5, 19–23 (1988).

Riekerk, H. The mobility of phosphorus, potassium, and calcium in a forest soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 35, 350–356 (1971).

Rigol, A., Vidal, M. & Rauret, G. An overview of the effect of organic matter on soil–radiocaesium interaction: implications in root uptake. J. Environ. Radioact. 58, 191–216 (2002).

Rosén, K. & Vinichuk, M. Potassium fertilization and 137Cs transfer from soil to grass and barley in Sweden after the Chernobyl fallout. J. Environ. Radioact. 130, 22–32 (2014).

Sanada, Y., Sugita, T., Nishizawa, Y., Kondo, A. & Torii, T. The aerial radiation monitoring in Japan after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident. Prog. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 4, 76–80 (2014).

Forest, S. Division. Classification of forest soil in Japan (1975). Bull. Gov. For. Exp. Stn. 280, 1–28 (1976).

Ikeda, S., Kaneko, S., Akama, A. & Takahashi, M. Methods for assessing the spatial distribution and dynamics of radiocesium in forest soils. Bull. FFPRI 13, 137–145 (2014).

Kuroda, K., Kagawa, A. & Tonosaki, M. Radiocesium concentrations in the bark, sapwood and heartwood of three tree species collected at Fukushima forests half a year after the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear accident. J. Environ. Radioact. 122, 37–42 (2013).

Committee of methods of soil nutrients analysis. Methods of soil nutrients analysis for measurement of soil fertility (in Japanese) (Yokendo, 1978).

R Core Team. R. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. http://www.r-project.org/ (2017).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1, https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01 (2015).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. http://cran.r-project.org/package=lmerTest (2016).

Helsel, D. R. Statistics for Censored Environmental Data Using Minitab and R, 2nd Edition. (John Wiley & Sons, 2012).

Lee, L. NADA: Nondetects and Data Analysis for Environmental Data. https://cran.r-project.org/package=NADA (2017).

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. (i) Results of Airborne Monitoring Survey in Hokkaido and (ii) Revision to the Results of Airborne Monitoring Survey over the Eastern Part of Japan with Detailed Consideration of the Influence of Natural Radionuclides. http://radioactivity.nsr.go.jp/en/contents/6000/5188/24/203_e_0727_14.pdf (2012).

Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. National Land Numerical Information Administrative Zones data. http://nlftp.mlit.go.jp/ksj-e/gml/datalist/KsjTmplt-N03.html (2016).

Wickham, H. ggplot2 elegant graphics for data analysis. (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. Download service of fundamental geospatial data. https://fgd.gsi.go.jp/download/menu.php (2011).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by research grant #201501 of Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute (FFPRI) and was also funded by the Forestry Agency. This research was partly conducted under collaborative research projects with Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA). We would appreciate the cooperation of Dr. Y. Ishii, Dr. T. Niizato, Mr. K. Mitachi and Mr. T. Watanabe from JAEA for their air dose rate measurement, Dr. M. Takahashi, Dr. A. Akama, Mr. T. Kawasaki, Dr. N. Imamura, Dr. S. Ohashi, Mr. S. Ikeda, Dr. T. Yamada, Dr. S. Saito, Dr. K. Yazaki, Dr. T. Kajimoto from FFPRI for field sampling, measurements and sample analysis, and Dr. S. Kaneko and Dr. T. Takano from FFPRI for facilitating the project. We would like to thank the village office of Kawauchi and the members of the Forest Management Center for their cooperation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K. and K.H. designed this study. M.K. built the datasets and performed the analysis with help from K.N. While all the authors were involved in fieldwork and sample preparation, K.H. and J.N. were responsible for soil physicochemical analysis. M.K. and J.N. were responsible for radioactivity measurements. K.H. conceived of and facilitated the project and monitoring component. M.K. wrote the manuscript, and all authors contributed to discussion and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Komatsu, M., Hirai, K., Nagakura, J. et al. Potassium fertilisation reduces radiocesium uptake by Japanese cypress seedlings grown in a stand contaminated by the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident. Sci Rep 7, 15612 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15401-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15401-w

This article is cited by

-

Radiocesium mobility in different parts of the two major tree species in Fukushima

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Explaining the variation in 137Cs aggregated transfer factor for wild edible plants as a case study on Koshiabura (Eleutherococcus sciadophylloides) buds

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Cellular-level in planta analysis of radial movement of minerals in a konara oak (Quercus serrata Murray) trunk

Journal of Wood Science (2022)

-

Decadal trends in 137Cs concentrations in the bark and wood of trees contaminated by the Fukushima nuclear accident

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Effects of species and geo-information on the 137Cs concentrations in edible wild mushrooms and plants collected by residents after the Fukushima nuclear accident

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.