Abstract

The formation of nucleosides in abiotic conditions is a major hurdle in origin-of-life studies. We have determined the pathway of a general reaction leading to the one-pot synthesis of ribo- and 2′-deoxy-ribonucleosides from sugars and purine nucleobases under proton irradiation in the presence of a chondrite meteorite. These conditions simulate the presumptive conditions in space or on an early Earth fluxed by slow protons from the solar wind, potentially mimicking a plausible prebiotic scenario. The reaction (i) requires neither pre-activated precursors nor intermediate purification/concentration steps, (ii) is based on a defined radical mechanism, and (iii) is characterized by stereoselectivity, regioselectivity and (poly)glycosylation. The yield is enhanced by formamide and meteorite relative to the control reaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

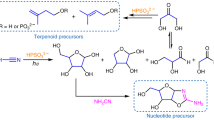

In the consensus “RNA world” scenario framing the Origin of Life, the generation of nucleosides in abiotic conditions remains the major initial hurdle. The one-pot formation of nucleosides from formamide NH2CHO was reported1 but without a detailed mechanistic insight into the sequence of contributing chemical events. The experimental set-up consisted of formamide, of meteorites as catalysts, and of a 170 MeV proton beam as energy source modelling the Solar Wind radiation. In these conditions the formation of cytidine, uridine, adenosine, and thymidine was observed without isolation and/or purification of specific intermediates, along with a variety of organic compounds including nucleobases (cytosine, uracil, adenine, guanine, and thymine), carbohydrates (noticeably, ribose and 2-deoxy-ribose), aminoacids and carboxylic acids.

Formamide is among others the most intensively studied chemical precursor for prebiotic syntheses2,3,4,5. It has been detected in dense diffuse clouds in interstellar space in the galactic habitable zone6, in comets7 and satellites8. For the prebiotic relevance of formamide see SI # 1.

Nucleosides are made of two components: heterocyclic nucleobases and carbohydrates. Nucleobases are easily synthesized under prebiotic conditions2,3,9 and have marked stability. Carbohydrates are more problematic, both for their synthesis and for their stability8,9,10. Still, the prebiotic synthesis of numerous carbohydrates was recently reported1,11,12,13 including, among others, ribose and 2-deoxyribose13.

Due to the hurdles surrounding the formation of β-glycosidic bonds between nucleobases and sugars (for a recent review see14) plausibility of nucleosides in a prebiotic context has been disputed. This motivated recent efforts aimed at elaborating chemical routes to nucleosides which do not involve the β-glycosylation step. It has recently been reported that pyrimidine ribonucleosides are afforded by the oxazoline chemistry15, recently revisited16,17, encompassig formamide as solvent for the thiolysis and phosphorylation of anhydronucleoside intermediates18. Alternatively, purine ribonucleosides are synthesized through the formamido pyrimidines (FPy) chemistry19, requiring formamide in the N-formylation of amino pyrimidine intermediates for the purine ring-closure. This reaction is the reverse version of the previously reported formation of FPy by treatment of purine nucleosides with formamide20, described in the cyclic conversion of purine into pyrimidine nucleobases9. Remarkably, formamide plays a role in both pathways.

Prebiotic oxazoline and formamido pyrimidine syntheses are both multi-steps procedures based on the construction of the heterocyclic nucleobase scaffold on a pre-formed and anomerically functionalized carbohydrate. The results obtained define two different, equally ingenuous and informative, routes to the ex novo synthesis of nucleosides. However, the repeatedly required interventions of an operator, which are necessary in both oxazoline- and formamido pyrimidine-based syntheses, justify caution about their prebiotic plausibility. This leads us to ask: does a simpler, more direct reaction pathway exists which allows for the one-pot synthesis of nucleosides via formation of the β-glycosidic bond between separately preformed sugar and nucleobase moieties? The same question was asked by Orgel and collaborators more than 40 years ago15,21.

Since nucleobases and carbohydrates are produced by independent reactions from formamide22, including proton irradiation conditions1, we have analyzed the possibility that the β-glycosidic bond might form directly between them under suitable prebiotic conditions, challenging the endergonic character of the reaction. Proton irradiation looked to be the appropriate choice for this purpose. Given the known induction of radical species by proton irradiation, the results are interpreted and discussed in the frame of radical chemistry.

Results

Irradiation experiments of nucleobases and carbohydrates were performed in three experimental conditions: 1, carbohydrate and adenine in solid film; 2, carbohydrate and adenine in formamide; 3, carbohydrate and adenine in formamide in the presence of powdered NWA 1465, selected as representative chondrite meteorite. Inorganic and organic composition, and cosmo-origin data of NWA 1465 are in SI # 2.

The solid film of adenine and carbohydrate (2-deoxyribose or ribose), or their solution in formamide (2.5 mL), with or without NWA 1465 powder (1.0% in weight, corresponding to 28 mg), was irradiated at 243 K with 170 MeV protons for 3 min. The uniform proton field was bounded to 10 × 10 cm2 by the collimator system. The averaged linear energy transfer (LET) was 0.57 keV/μm and the calculated absorbed dose was 6 Gy. The presence of organics in the original sample of NWA 1465, observed in the ppb range23, was prevented by extracting the powder with NaOH (0.1 N), CHCl3-CH3OH (2:1 v/v) and sulfuric acid. The endogenous organics possibly present were removed by the extracting mixture during the treatment, and the remaining powder was used for the irradiation experiments. In agreement with previous data, the treated and untreated NWA 1465 powder performed as catalyst similarly during formamide irradiation (Table 1, note c)13. Materials and Methods are detailed in experimental methods and in SI # 3. The analysis was limited to products ≥1 ng/mL and the yield was calculated as percentage (%) of product per starting adenine.

We focused on the detection of nucleosides and nucleoside derivatives by ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography on-line to orbitrap-mass-spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS; Q Exactive-orbitrap mass analyzer). The structure of products was unambiguously defined by comparison of the mass fragmentation peaks with original commercial samples and with specifically laboratory-prepared samples as standards. The nucleosides showed all the expected molecular ions (M) and the specific fragment ions. When necessary, the assignment was further confirmed by the Addition Method19 and by Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI) TOF analysis.

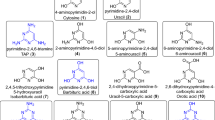

The formation of mono- and poly-glycosylated nucleosides was observed: irrespective to experimental conditions, the reaction of adenine (1) with 2-deoxyribose (2) afforded α-D-2′-deoxy-ribofuranosyl adenine (3), β-D-2′-deoxy-ribofuranosyl adenine (4), α-D-2′-deoxy-ribopyranosyl adenine (5), and β-D-2′-deoxypiranosyl adenine (6). Poly-glycosylated N6-2′-deoxy-ribofuranosyl-(7a) and N6-2′-deoxy-ribopyranosyl-2′-deoxyadenosine isomers (7b) were also detected and assigned on the basis of comparison with authentic standards prepared as reported24 (Fig. 1; Table 1, entries 1–3). Figure 2 shows as an example the UHPLC profile for the irradiation of adenine (1) and 2-deoxyribose (2) in formamide and NWA 1465.

HPLC chromatographic profile for the irradiation of adenine (1) and 2-deoxyribose (2) in NH2CHO and NWA 1465. Peak A (21.026 min): α-dpA (5). Peak B (23.944 min): β-dpA (6). Peak C (26.176 min): α-dfA (3). Peak D (26.684 min) β-dfA (4). Peak E (31.347-34.388 min): df(p)A (7a–b). The magnification reports the same reaction mixture co-injected with a standard sample of α-dpA (5).

The complete set of UHPLC-MS/MS data, chromatographic profiles, and selected m/z fragmentation spectra are in SI #4. Chromatographic profiles also reports the magnification of the same reaction mixtures co-injected with standard nucleoside samples. The synthesis and analytical data of standard nucleosides are in SI #5.

MALDI TOF analysis (Fig. 3) of the reaction in formamide and NWA 1465 confirmed the presence of products (3–6) and (7a-b). The complete set of MALDI TOF analyses is SI#6 A-E. Higher molecular weight poly-glycosylated derivatives, corresponding to the addition of three (m/z = 484), four (m/z = 600), five (m/z = 716) and six (m/z = 832) sugar moieties, were also detected. In the irradiation of the solid film, the poly-glycosylation process progressed to a lesser extent, reaching the addition of up to four sugar moieties (SI #6-D). The m/z ions of higher molecular weight poly-glycosylated derivatives were characterized by the loss of a water molecule per novel glycosidic bond, as a consequence of the addition/elimination reaction. These data were further confirmed by the MS/MS analysis of the peak at 36.8 min in the HPLC chromatographic profile of the irradiation of adenine (1) and 2-deoxyribose (2) in formamide, corresponding to a tetra glycosylated derivative (Figure SI #4-I). The absence of the peaks of others poly-glycosylated compounds might be due to their low abundance. In this latter case, the possibility of the presence of non-covalent aggregates, rather than covalently-bound products, cannot be completely ruled out. In extant living systems, poly-glycosylated nucleosides bearing oligosaccharide side chains have been detected in tRNAMet molecules involved in yeasts and plants replication processes25. They are products of post-translational modifications in humans and play key roles in cellular physiology and genotoxic stress response26.

The reaction of adenine (1) with ribose (9) afforded α-D-ribofuranosyl adenine (10), β-D-ribofuranosyl adenine (11), α-D-ribopyranosyl adenine (12) and β-D-ribopyranosyl adenine (13). In this latter case, the signals of (10) and (13) overlapped in the UHPLC profile, according to a previously reported chromatographic pattern19. Poly-glycosylated derivatives were detected neither by UHPLC-MS/MS nor by MALDI TOF analyses (Fig. 1; Table 2, entries 1–3).

2′-Deoxyribosides form more efficiently than ribosides, pyranosides prevail over furanosides, the β-isomer over the α-isomer, and the formation of nucleosides is always enhanced by formamide and by the meteorite. The synthesis of 2′-deoxyribosides and of ribosides progressed from acceptable to high yield. 2-D-deoxyribose (2) showed a reactivity higher than D-ribose (9). Irrespective of the experimental conditions, the highest yields were obtained in the presence of formamide and NWA 1465. The irradiation of adenine (1) and 2-deoxyribose (2) in dry state or in formamide afforded pyranosides (5–6) in yield higher than that of the furanoside counterparts (3,4) (24.9% versus 12.3%, and 42.7% versus 24.4%, respectively. Table 1, entries 1 and 2). Similar results were observed for the reaction of D-ribose, where the pyranoside (12) prevailed over furanoside (11) [the ratio between (10) and (13) could not be determined due to overlapping peaks]. These data are in agreement with the prevalence of the pyranoside form for carbohydrates2 and9 when dissolved in formamide, as evaluated by 13C-NMR analysis (Table 3. 83.3% versus 17.7%, and 81.8% versus 18.2%, respectively). Similar results were observed by 13C-NMR analysis in water, where the furanose form accounts for 12% of all the ribose in solution27 (SI#7D). Pyranosides have been suggested as plausible carbohydrate alternatives in preRNA molecules28 instead of ribofuranose units. 13C-NMR procedure, spectra and chemical shifts of pyranoside and furanoside isomers in formamide and H2O are in SI # 7.

Noticeably, furanosides 3–4 and 11 were the main isomers in the presence of NWA 1465, showing the important role of the mineral surface at stabilizing the different anomeric forms (Tables 1, 2). The tendency toward stabilizing (9) in its furanose form was previously reported on silica, associated with the prevalence of the β over the α stereo-isomer29. The formation of silicate five-membered diolate ring chelate30, characterized by the appropriate value of the O-C-C-O dihedral angle31, was reported to enhance the accumulation of the furanose form32. Furthermore, the elimination of water during the drying process increases the amount of the β-anomer33. The influence of zinc polydentate complexes on the formation of high proportion of β-furanose (50%) was also reported29. The formation of the latter is probably favored for geometrical reasons. From NMR results, the OH group at C5 interacts preferentially with the silica surface, so that the complexation with cations occurs with the OH at C2 and C3. These are more accessible because they are positioned on the opposite side of the molecular plane favoring the stabilization of the β-anomer.

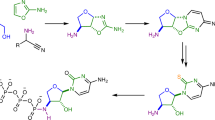

We next evaluated the possible mechanism of the proton radiation-induced N-glycosylation. There is a consensus in the literature that the primary effect of ionizing radiation (like proton irradiation) on sugars is the abstraction of hydrogens from C-H bonds34,35,36,37,38. Hydrogen abstraction preferentially occurs on the carbons which are connected to an oxygen because of the electron withdrawing effect by the latter. For this reason, formation of C2-centered radicals of 2-deoxyribose is less likely as compared to that of radicals centered at other carbons36. The most stable product in the radiolysis of purine nucleobases is a C8-hydrogenated adduct39,40. M3 formed via the recombination of radiolysis products M1 and M2 (Fig. 4 and Figure SI #8-A) loses water in an exothermic reaction step (the computed reaction free energy change for this step is −13.9 kcal/mol). Based on computations using simplified models (for details see SI#8 and SI#10) this proceeds with the very low activation energy of 12.7 kcal/mol if catalytic formamide molecules (in the formamidic acid tautomeric form) are included in the model. The transition state complex for the formamide-catalyzed water abstraction step is depicted in Figure SI#8-B. The product of the dehydration step, compound M4, then isomerizes to the nucleotide product in two consecutive reaction steps with participation of two atomic hydrogens. In the first step the C8-position of the nucleobase loses a hydrogen, while in the second step the newly formed radical center at C1′ is saturated with another atomic hydrogen and leads to the nucleoside product M5. Since in these two steps the attacking atomic hydrogens form a covalent bond first with the C8 hydrogen and later with the C1′ carbon, both steps are markedly exothermic (the computed reaction free energies changes being −58.3 and −90.9 kcal/mol) and proceed essentially without an activation barrier.

Proposed reaction mechanism for the nucleoside formation assuming adenine base and 2-deoxy ribose in its pyranose forms. R = OH, H for ribose and deoxyribose, respectively. For a more detailed mechanistic model see Fig. SI #8-A.

Based on the experimental data, 2-D-deoxyribose (2) is more active in the nucleoside formation reaction than D-ribose (9). Quantum chemical model calculations (SI #9, Table SI #9-A) suggest that a hydroxyl attached to the adjacent carbon has only a marginal effect on C-H bond dissociation energies. Because of this, there is no reason to assume that significant differences might occur in the rate of C1-radical formation from (9) and (2). On the other hand, there might be a difference in the degradation rate of these radicals, because of the absence of the 2-OH group in the 2-deoxy form. One of the main degradation channels of polyalcohol radicals is the loss of water from two vicinal hydroxyls located next to the radical center41. Because of the lack of the 2-OH, this degradation mechanism is irrelevant to 2-deoxyribose (Figure SI #9-B). Thus, the higher activity of 2-deoxyribose in the glycosidic bond formation might be associated with its enhanced resistance towards degradation.

Finally, we studied the nucleobase regioselectivity of the glycosylation. The glycosylation process under irradiation conditions selectively afforded N9 isomers, which are the isomers that molecular evolution has selected for the formation of nucleic acids. If electron delocalization enables the appearance of the radical character on nitrogens other than the N9 of the aromatic ring (which is the case of adenine), then the water-elimination from the adduct formed between the nucleobase and carbohydrate radicals (similar to the conversion of M3 to M4 in Fig. 4) drives the reaction towards the stabilization of the glycosidic bond. This however assumes that one H is available on the nitrogen carrying the radical character (the OH is coming from the carbohydrate radical). If no H is available on the nitrogen (which is for instance the case of N7), then the high-energy adduct cannot be stabilized and will most likely fall apart (Fig. 5). This mechanism is probably responsible for the absence of glycosylation on N1 and N7 of adenine, justifying the observed formation of N6-glycosylated adducts.

Discussion and Conclusions

The major interest of a prebiotically plausible synthesis of nucleosides resides in the hurdles that this topic has met. In its general purport, the term prebiotic refers to compounds or processes that are robust, energetically not excessively demanding, based on commonly available starting materials. Nucleosides can be obtained through de novo synthesis by the oxazoline chemistry15,16,17 or by the formamido pyrimidine chemistry19. Both pathways are ingenuous, afford nucleosides in good yields, and provide important data on nucleoside chemistry. The strengths of the oxazoline-based syntheses are their high regio- and stereoselectivity, the weaknesses are the multi-step procedures involved and the fact that they only apply to ribonucleosides. The formamido pyrimidine-based syntheses are high regioselective, moderately stereoselective, multi-step, only apply to purines and afford a mixture of furanosides and pyranosides. The prebiotic worth of these syntheses is inversely proportional to the procedural complexities involved, requiring numerous concentration, purification and supplementation steps, designed to specifically overcome intermediate reactions bottlenecks. How do other approaches, and the results presented here compare with these previous studies?

The difficulty of formation of the β-glycosidic bond between preformed moieties14 may be overcome considering alternative routes, as reaction in dry phase or radical chemistry. Considering that this reaction is substantially a dehydration process, Orgel and coworkers21 studied it by treating adenine and guanine with D-ribose by heating in dry phase. The reaction yielded 6-ribosylamino adenine and 2-ribosylamino guanine as the only recovered products. This result showed that the reaction in dry phase does not allow for an adequate regioselectivity, since the exocyclic nitrogen atoms are more reactive as nucleophiles than the endocyclic N9- or N1-atoms. Better regioselectivity was observed when performing the reaction in the presence of magnesium salts and inorganic phosphates, affording riboadenosine and riboguanosine in low yield (4% and 9%, respectively) as a mixture of α- and β-isomers.

As for the radical chemistry approach, the data presented in this paper define the pathway of the reaction and the characterization of the products. The reaction is one-pot, high-yield, stereo- and regioselective, and applies both to ribo- and deoxyribonucleosides. In addition, in the presence of one representative part of the meteorite tested, the carbonaceous chondrite NWA 1465, it favors furanosides over pyranosides, which are the anomeric forms present in extant nucleic acids.

Methods

Formamide, D-ribose, 2-D-deoxyribose and adenine were purchased from Aldrich. NWA 1465 was obtained from Sahara-nayzak, Asnieres sur Seine, France. Gas-chromatography mass-spectrometry (GC-MS) analyses were performed with a LC/GG MS Combo Agilent and Shimadzu GC-MS QP5050A with a Variant CP8944 column (WCOT fused silica, film thickness 0.25 μm, stationary phase VF-5ms, Øί 0.25 mm, lenght 30 m). UHPLC were performed on Ultimate 3000 Rapid Resolution system (DIONEX, Sunnyvale, USA) using Reprosil C18 column (2,5 μm × 150 mm × 2.0 mm). MALDI were performed on Q-Exactive (Thermo). NMR spectra were acquired with a Bruker Avance III 500 spectrometer. Computations were carried out at B3LYP/6-31 + G* level within the COSMO continuum solvent approximation.

Irradiation experiments

General procedure

The solid film (12 mg) of adenine and carbohydrates, or the solution of adenine (0.04 mmol) and carbohydrate (2-deoxyribose or ribose; 0.008 mmol) in formamide (2.0 mL), with or without NWA 1465 meteorite powder (1.0% in weight with respect to formamide, corresponding to mg) were irradiated at 243 K with 170 MeV protons generated by the Phasotron facility of the Joint International Nuclear Institute (JINR; Dubna, Russia) for 3 min. The uniform proton field was bounded to 10×10 cm2 by the collimator system. The averaged linear energy transfer (LET) was about 0.57 keV/μm and the calculated absorbed dose was 6 Gy.

Further details of the experiments and computations are given in the Supplementary Material.

Change history

12 March 2019

A correction to this article has been published and is linked from the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has been fixed in the paper.

References

Saladino, R. et al. Meteorite-catalyzed syntheses of nucleosides and of other prebiotic compounds from formamide under proton irradiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, E2746–E2755 (2015).

Saladino, R., Crestini, C., Pino, S., Costanzo, G. & Di Mauro, E. Formamide and the origin of life. Phys Life Rev. 9, 84–104 (2012).

Saladino, R., Botta, G., Pino, S., Costanzo, G. & Di Mauro, E. Genetics first or metabolism first? The formamide clue. Chem Soc Rev. 41, 5526–5565 (2012).

Ferus, M. et al. High-energy chemistry of formamide: A unified mechanism of nucleobase formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, 15030–15035 (2014).

Saitta, A. M. & Saija, F. Miller experiments in atomistic computer simulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 13768–13773 (2014).

Adande, G. R., Woolf, N. J. & Ziurys, L. M. Observations of interstellar formamide: availability of a prebiotic precursor in the galactic habitable zone. Astrobiology. 13, 439–453 (2013).

Bockelee-Morvan, D. et al. New molecules found in comet C/1995 O1 (Hale-Bopp). Investigating the link Between Cometary and Interstellar Material. Astron Astrophys. 353, 1101–1114 (2000).

Benner, S. A., Kim, H. J. & Carrigan, M. A. Asphalt, Water, and the Prebiotic Synthesis of Ribose, Ribonucleosides, and RNA. Acc Chem Res. 45, 2025–2034 (2012).

Saladino, R., Crestini, C., Costanzo, G. & Di Mauro, E. Advances in prebiotic syntheseis of nucleic acids bases. Implications for the origin of life. Curr Org Chem. 8, 1425–1443 (2004).

Ricardo, A., Carrigan, M. A., Olcott, A. N. & Benner, S. A. Borate minerals stabilize ribose. Science. 303, 196 (2004).

Ritson, D. & Sutherland, J. D. Prebiotic synthesis of simple sugars by photoredox systems chemistry. Nature Chem. 11, 895–899 (2012).

Kim, H. J. et al. Synthesis of carbohydrates in mineral-guided prebiotic cycles. J. Am Chem Soc. 133, 9457–9468 (2011).

Rotelli, L. et al. The key role of meteorites in the formation of relevant prebiotic molecules in a formamide/water environment. Sci Rep. 6, 38888, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38888 (2016).

Sutherland, J. D. The Origin of Life-Out of the Blue. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 55, 104–121 (2016).

Sanchez, R. A. & Orgel, L. S. Studies in prebiotic synthesis and photoanomerization of pyrimidine nucleosides. J Mol Biol. 47, 531–543 (1970).

Powner, M. W., Gerland, B. & Sutherland, J. D. Synthesis of activated pyrimidine ribonucleotides in prebiotically plausible conditions. Nature. 459, 239–242 (2009).

Powner, M. W. & Sutherland, J. D. Phosphate-mediated interconversion of ribo- and arabino- configured prebiotic nucleotide intermediates. Angew Chem Int Ed. 49, 4641–4643 (2010).

Xu, J. et al. A prebiotically plausible synthesis of pyrimidine β-ribonucleosides and their phosphate derivatives involving photoanomerization. Nature Chem. 9, 303–309 (2017).

Becker, S. et al. A high-yielding, strictly regioselective prebiotic purine nucleoside formation pathway. Science. 352, 833–836 (2016).

Saladino, R. et al. Mechanism of degradation of purine nucleosides by formamide. Implications for chemical DNA sequencing procedures. J Am Chem Soc. 118, 5615–5619 (1996).

Fuller, W. D., Sanchez, R. A. & Orgel, L. E. Studies on prebiotic synthesis. VI. Synthesis of purine nucleosides. J. Mol. Biol. 67, 25–33 (1970).

Šponer, J. E. et al. Emergence of the First Catalytic Oligonucleotides in a formamide Based Origin Scenario. Chem Eur J. 22, 3572–3586 (2016).

Callahan, M. P. et al. Carbonaceous meteorites contain a wide range of extraterrestrial nucleobases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 13995–13998 (2011).

Price, N. E., Catalano, M. J., Liu, S., Wang, Y. & Gates, K. S. Chemical and structural characterization of inter-strand cross-links formed between abasic sites and adenine residues in duplex DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 3434–3441 (2015).

Pearson, D. et al. LC-MS based quantification of 2′-ribosylated nucleosides Ar(p) and Gr(p) in tRNA. Chem Commun. 47, 5196–5198 (2011).

Martello, R., Mangerich, A., Sass, S., Dedon, P. C. & Burkle, A. Quantification of cellular poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by stable isotope dilution mass spectrometry reveals tissue- and drug-dependent stress response dynamics. ACS Chem Biol. 8, 1567–1575 (2013).

Ortiz, P., Fernández-Bertrán, J. & Reguera, E. Role of the anion in the alkali halides interaction with D-ribose: a 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy study. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 61, 1977–83 (2005).

Eschenmoser, A. & Dobler, M. Why pentose and not hexose nucleic acids? Helv Chim Acta. 75, 218–259 (1992).

Akouche, M. et al. Thermal Behavior of d-Ribose Adsorbed on Silica: Effect of Inorganic Salt Coadsorption and Significance for PrebioticChemistry. Chem Eur J. 22, 1–14 (2016).

Benner, K., Klüfers, P. & Schuhmacher, J. Z. Synthesis and Structure of a Tetrahydroxydisilane and a Trihydroxycyclotrisiloxane with All the OH Functions in cis Position. Inorg Allg Chem. 625, 541–543 (1999).

Benner, K., Klüfers, P. & Vogt, M. Hydrogen-Bonded Sugar-Alcohol Trimers as Hexadentate Silicon Chelators in Aqueous Solution. Angew Chem Int Ed. 42, 1058–1062 (2003).

Lambert, J. B., Lu, G., Singer, S. R. & Kolb, V. M. Silicate Complexes of Sugars in Aqueous Solution. J. Am Chem Soc. 126, 9611–9625 (2004).

Georgelin, T. et al. Stabilization of ribofuranose by a mineral surface. Carbohydr Res. 402, 241–244 (2015).

Schuchmann, M. N. & von Sonntag, C. Radiation chemistry of carbohydrates. Part 14. Hydroxyl radical induced oxidation of D-glucose in oxygenated aqueous solution. J. Chem Soc Perkin Trans 2. 0, 1958–1963 (1977).

Madden, K. P. & Fessenden, R. W. ESR study of the attack of photolytically produced hydroxyl radicals on α-methyl-D-glucopyranoside in aqueous solution. J. Am Chem Soc. 104, 2578–2581 (1982).

Miaskiewicz, K. & Osman, R. Theoretical study on the deoxyribose radicals formed by hydrogen abstraction. J. Am Chem Soc. 116, 232–238 (1994).

von Sonntag C. Free radical reactions of carbohydrates as studied by radiation techniques. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 37, 7–77 (19809.

Kochetkov, N. K. Radiation Chemistry of Carbohydrates, Pergamon Press Oxford, 1979.

Wetmore, S. D., Boyd, R. J. & Eriksson, L. A. Theoretical Investigation of Adenine Radicals Generated in Irradiated DNA Components. J. Phys Chem B. 102, 10602–10614 (1998).

Wetmore, S. D., Boyd, R. J. & Eriksson, L. A. Comparison of Experimental and Calculated Hyperfine Coupling Constants. Which Radicals Are Formed in Irradiated Guanine? J. Phys Chem B. 102, 9332–9343 (1998).

Von Sonntag, C. Carbohydrate radicals: from ethylene glycol to DNA strand breakage. Int J Rad Biol. 90, 416–422 (2014).

Crimmins, M. T. New developments in the enantioselective synthesis of cyclopentyl carbocyclic nucleosides. Tetrahedron 54, 9229–9272 (1998).

Acknowledgements

MIUR Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università della Ricerca and Scuola Normale Superiore (Pisa, Italy), project PRIN 2015 STARS in the CAOS - Simulation Tools for Astrochemical Reactivity and Spectroscopy in the Cyberinfrastructure for Astrochemical Organic Species, cod. 2015F59J3R, is acknowledged. Financial support from the grant GAČR 17-05076 S and from the project LO1305 (NPU programme) of the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic is greatly acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.S., A.R., E.K. and E.D.M. designed research; R.S., B.M.B., L.B., A.M.T. and M.K. performed research; G.N.T., A.R., E.K. performed irradiations; M.J., B.R. and T.G. performed NMR analyses; J.S. and J.E.S. performed theoretical analysis; R.S., E.K., J.S., J.E.S., T.G. and E.D.M. analysed data; R.S., J.S., J.E.S. and E.D.M. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saladino, R., Bizzarri, B.M., Botta, L. et al. Proton irradiation: a key to the challenge of N-glycosidic bond formation in a prebiotic context. Sci Rep 7, 14709 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15392-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15392-8

This article is cited by

-

Physical non-equilibria for prebiotic nucleic acid chemistry

Nature Reviews Physics (2023)

-

Regioselective ribonucleoside synthesis through Ti-catalysed ribosylation of nucleobases

Nature Synthesis (2023)

-

Prebiotic chemical refugia: multifaceted scenario for the formation of biomolecules in primitive Earth

Theory in Biosciences (2022)

-

Ariel – a window to the origin of life on early earth?

Experimental Astronomy (2022)

-

2,6-diaminopurine promotes repair of DNA lesions under prebiotic conditions

Nature Communications (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.