Abstract

Lactate/lactic acid is an important chemical compound for the manufacturing of bioplastics. The unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 can produce lactate from carbon dioxide and possesses d-lactate dehydrogenase (Ddh). Here, we performed a biochemical analysis of the Ddh from this cyanobacterium (SyDdh) using recombinant proteins. SyDdh was classified into a cyanobacterial clade similar to those from Gram-negative bacteria, although it was distinct from them. SyDdh can use both pyruvate and oxaloacetate as a substrate and is activated by fructose-1,6-bisphosphate and repressed by divalent cations. An amino acid substitution based on multiple sequence alignment data revealed that the glutamine at position 14 and serine at position 234 are important for the allosteric regulation by Mg2+ and substrate specificity of SyDdh, respectively. These results reveal the characteristic biochemical properties of Ddh in a unicellular cyanobacterium, which are different from those of other bacterial Ddhs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lactate/lactic acid is an organic acid used for the formation of poly(lactic acid) (PLA), which is a widely used biodegradable polyester1,2. Stereocomplex PLA is formed using enantiomeric PLA, poly(l-lactide) and poly(d-lactide), which enhances the mechanical properties, thermal stability, and hydrolysis resistance3,4. Lactate can be produced from petroleum; however, chemical synthesis generates a mixture of enantiomers. Optically pure l-lactate can be produced by large-scale microbial fermentation using, for example, Lactobacillus and Bacillus strains5,6. On the other hand, d-lactate production is required to produce stereocomplex PLA, but the process of d-lactate production has not been commercialised7. Thus, optically pure d-lactate production is important so that biorefinery can meet the demand for value-added bioplastic construction.

d-lactate is synthesised by NAD-dependent d-lactate dehydrogenase (Ddh, EC 1.1.1.28), whose biochemical properties have been studied using heterotrophic bacteria, including lactic acid bacteria8,9,10. Ddh catalyses oxidoreductase reactions between pyruvate and d-lactate using NADH as a co-factor. Ddh is phylogenetically distinguished from NAD-dependent l-lactate dehydrogenase (Ldh, EC 1.1.1.27) and belongs to a new group in the 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase family11. Generally, Ldh is allosterically activated in the presence of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) by increasing substrate affinities to the enzymes12,13. Ddhs from Gram-negative bacteria, including Fusobacterium nucleatum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are activated by divalent cations such as Mg2+ 14. The S 0.5 values of Ddhs from Fusobacterium nucleatum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa for pyruvate are reduced in the presence of Mg2+ 14. Ddhs from Fusobacterium nucleatum, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli are activated by FBP and citrate14. On the other hand, Ddh from Escherichia coli is not activated by Mg2+, demonstrating that the properties of Ddhs are diverse among Gram-negative bacteria14 Ddhs from Gram-positive bacteria, including Pediococcus acidilactici DSM 20284 and Pediococcus pentosaseus ATCC 25745, are hardly activated by divalent cations15,16. Thus, the allosteric regulation of lactate dehydrogenases is dependent on the species of bacteria.

Lactate production by heterotrophic bacteria requires external carbon sources such as glucose, which account for a large proportion of the production cost. Cyanobacteria, which perform oxygenic photosynthesis and fix CO2 via the Calvin-Benson cycle, have the potential to produce valuable products using CO2 as a carbon source. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (hereafter Synechocystis 6803) is a unicellular, non-nitrogen fixing cyanobacterium that is widely used for basic research and contains Ddh (slr1556)17. Synechocystis cells can consume d-lactate under continuous light conditions18 and excrete d-lactate under dark, anaerobic conditions19. Biochemical analysis revealed that the Ddh from Synechocystis 6803 (SyDdh) is able to utilise both NADH and NADPH as cofactors18. SyDdh can catalyse pyruvate, hydroxypyruvate, glyoxylate, and d-lactate, but physiologically, it functions as a pyruvate reductase18. Ddh from Lactobacillus delbrueckii 11842 is a NADH-dependent dehydrogenase, and the substitution of three amino acid residues at positions 176~178 increases the k cat/K m for NADPH by 184-fold10. For cyanobacteria, the key residues involved in allosteric regulation are unclear.

In this study, we performed a biochemical analysis of SyDdh and identified two amino acid residues that alter the specificities and affinities to substrates and allosteric regulation by Mg2+ of SyDdh.

Results

Affinity purification and biochemical characterisation of SyDdh

To analyse the biochemical properties of SyDdh, glutathione-S-transferase-tagged SyDdh (GST-SyDdh) was expressed and purified from the soluble fraction of Escherichia coli cell extract by affinity chromatography (Fig. 1A). The enzymatic activity of SyDdh was highest at pH 7.5 (Fig. 1B). The enzymatic activities were similar at 30~40 °C (Fig. 1B). A subsequent enzymatic assay was performed at 30°C and pH 7.5. The k cat value of SyDdh for pyruvate was 2.71 ± 0.26 s−1, and the S 0.5 value of SyDdh for pyruvate was 0.38 ± 0.04 mM (Table 1).

Biochemical analysis of Synechocystis 6803 d-lactate dehydrogenase (SyDdh). (A) Purification of GST-tagged SyDdh after separation by electrophoresis on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. The gel was stained with InstantBlue reagent. Arrowheads indicate the molecular weight. (B) Effect of pH (top) and temperature (bottom) on SyDdh activity. Data represent the relative values of the means from three independent experiments. For the enzyme assay, 60 pmol (or 0.0038 mg) of SyDdh was used. One unit of SyDdh activity was defined as the consumption of 1 μmol NADH per minute.

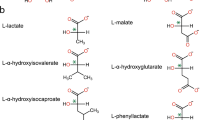

Since Ddh has broad substrate specificity to 2-ketoacid in other bacteria, we also measured SyDdh activity using oxaloacetate as a substrate. SyDdh was able to catalyse not only pyruvate but also oxaloacetate as a substrate (Fig. S1); the k cat value for oxaloacetate was 2.16 ± 0.41 s−1, and the S 0.5 value of SyDdh for oxaloacetate was 1.58 ± 0.76 mM (Table 1). The k cat/S 0.5 values of SyDdh for pyruvate and oxaloacetate were 7.14 ± 1.15 and 1.55 ± 0.38 s−1 mM−1, respectively (Table 1). Ddhs from lactic acid bacteria can catalyse phenylpyruvate15,16,20,21, but SyDdh could not catalyse phenylpyruvate as a substrate. The k cat value for NADH was 2.60 ± 0.25 s−1, and the S 0.5 value of SyDdh for NADH was 0.028 ± 0.002 mM, and therefore, k cat/S 0.5 was 94.33 ± 7.83 s−1 mM−1. SyDdh had no activity with NADPH as a cofactor in our enzymatic assay.

We have tried to excise GST-tag from SyDdh using Factor Xa but the GST-tag was not excised. Then, ddh ORF was cloned into pGEX6P-1 and GST-SyDdh proteins were expressed and purified. GST-tag from pGEX6P-1 was excised by HRV 3C protease (Fig. S2A). However, purification after excision of the GST-tag was not succeeded (Fig. S2A). We measured enzymatic activities using the mixtures including SyDdh without GST-tag, but the relative activity did not increase. Therefore, we performed subsequent experiments using the proteins with GST-tags.

Comparison of the amino acid sequence and the 3D structure of SyDdh

We then compared the amino acid sequence of SyDdh with those of d-lactate dehydrogenases from Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria by generating a phylogenetic tree using the maximum-likelihood method (Fig. 2). The phylogenetic tree of 36 Ddhs revealed distinct clusters for Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (Fig. 2). Cyanobacterial Ddhs were grouped with those from Gram-negative bacteria but were included in an independent clade (Fig. 2).

Phylogenetic analysis of the Ddhs from cyanobacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, and Gram-positive bacteria. Protein sequences and accession numbers were obtained from GenBank, followed by alignment using CLC Sequence Viewer software. A maximum-likelihood tree based on 262 conserved amino acids was generated using PHYML (http://www.atgc-montpellier.fr/phyml/). The bootstrap values were obtained from 500 replications.

Multiple sequence alignment analysis was then performed using nine Ddhs from cyanobacteria and three Ddhs from Gram-negative bacteria (Fig. 3). As mentioned above, Ddhs from Fusobacterium nucleatum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa have different biochemical properties from those of E. coli 14. Therefore, we searched for characteristic amino acid residues that were 1) conserved in Fusobacterium nucleatum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa but not in E. coli and 2) conserved in cyanobacteria. The amino acid residue glutamine at position 14 of SyDdh was relatively conserved among cyanobacteria, and the equivalent amino acid residues of Fusobacterium nucleatum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Ddhs were glutamate (Fig. 3). The amino acid residue serine at position 234 of SyDdh was conserved among all cyanobacteria examined and in E. coli, while the equivalent amino acid residues of Fusobacterium nucleatum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Ddhs were glycine (Fig. 3). To examine the location of amino acid residues at positions 14 and 234, we performed in silico analysis to predict 3D structure of SyDdh (Fig. 4A). SyDdh structure was generated from the 3D structures of Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a template (Fig. 4B). 3D structure of Ddh from Fusobacterium nucleatum was shown in Fig. 4C and superposition of SyDdh and Ddh from Fusobacterium nucleatum was described in Fig. 4D. These results indicate that SyDdh structure was similar to Ddhs from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Fusobacterium nucleatum and amino acid residues at positions 14 and 234 of SyDdh and equivalent residues of Ddhs from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Fusobacterium nucleatum were located at different domains (Fig. 4A~D).

3D-structures of Ddhs represented by cartoon diagrams. (A) Structure of SyDdh generated by SWISS-MODEL. (B) 3D-structure of Ddh from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (PDB ID: 3WWZ). (C) 3D-structure of Ddh from Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum ATCC 25586 (PDB ID: 3WWY). Amino acid residues at positions 14 and 234 of SyDdh and equivalent amino acid residues in Ddhs from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Fusobacterium nucleatum were marked red and blue respectively. (D) Superposition of SyDdh and Ddh from Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum ATCC 25586.

Amino acid substitutions altering the substrate specificity of SyDdh

To clarify the role of the amino acid residues in SyDdh, we changed the glutamine residue at position 14 to glutamate (the protein was named SyDdh_Q14E) and the serine residue at position 234 to glycine (the protein was named SyDdh_S234G). The SyDdh_Q14E and SyDdh_S234G proteins were expressed similarly in E. coli as were SyDdh proteins, and the recombinant proteins were purified by affinity chromatography (Fig. 5A).

Enzymatic assay of SyDdh with a single substituted amino acid residue. SyDdh_Q14E and SyDdh_S234G are SyDdh with the glutamine at position 14 substituted with glutamate and with the serine at position 234 substituted with glycine, respectively. (A) Purification of GST-tagged SyDdh_Q14E and SyDdh_S234G after separation by electrophoresis on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. The gel was stained with InstantBlue reagent. Arrowheads indicate the molecular weight. (B and C) Enzymatic activity in the presence of effectors. Each effector was added at a concentration of 2.5 mM. Ddh activity was measured at 30°C and pH 7.5 using 60 pmol SyDdhs. The graphs show the mean ± SD obtained from four independent experiments. Each activity of SyDdhs in the absence of effectors was set at 100%.

The k cat values of SyDdh_Q14E for pyruvate and oxaloacetate increased to 4.11 ± 0.71 and 2.38 ± 0.10 s−1, respectively (Table 1). The S 0.5 values of SyDdh_Q14E for pyruvate and oxaloacetate increased to 0.52 ± 0.10 and 1.71 ± 0.38 mM, respectively (Table 1). The k cat/S 0.5 values of SyDdh_Q14E for pyruvate and oxaloacetate were 7.98 ± 0.35 and 1.46 ± 0.31 s−1 mM−1, respectively, which were similar to those of SyDdh (Table 1).

The k cat values of SyDdh_S234G for pyruvate and oxaloacetate decreased to 1.71 ± 0.26 and 1.27 ± 0.24 s−1, respectively (Table 1). The S 0.5 value of SyDdh_S234G for pyruvate increased to 2.10 ± 0.18 mM, while that for oxaloacetate decreased to 0.59 ± 0.05 mM (Table 1). The k cat/S 0.5 value of SyDdh_S234G for pyruvate decreased to 0.82 ± 0.13 s−1 mM−1and that for oxaloacetate increased to 2.19 ± 0.52 s−1 mM−1 (Table 1).

SyDdh showed positive cooperativity (n H = 2.51 ± 0.11) for pyruvate, and the Hill coefficient of SyDdh_S234G decreased to n H = 1.64 ± 0.10 (Table 1). SyDdh_Q14E exhibited substrate inhibition by pyruvate, and the value of K i was 16.51 ± 5.98 mM (Table 1). Contrary to pyruvate, SyDdh and SyDdh_S234G exhibited substrate inhibition by oxaloacetate, K i = 8.56 ± 3.39 and 5.74 ± 1.04 mM, respectively (Table 1). SyDdh_Q14E did not show substrate inhibition by oxaloacetate, whose Hill coefficient was 0.95 ± 0.12 (Table 1).

Amino acid substitution altered the biochemical properties in the presence of several effectors

The enzymatic activities in the presence of various effectors were then examined at 30°C and pH 7.5. SyDdh activity increased to 134% in the presence of 2.5 mM FBP, while those of SyDdh_Q14E and SyDdh_S234G were both lower and not activated by FBP (Fig. 5B). Citrate slightly increased SyDdh activity to 116% of the level with effectors, and SyDdh_Q14E and SyDdh_S234G were also both activated by citrate (Fig. 5B) The addition of 2.5 mM NaCl and MgCl2 reduced SyDdh activity to ca 80% of the level without effectors (Fig. 5B). SyDdh_S234G activity did not decrease in the presence of NaCl and MgCl2, and SyDdh_Q14E activity markedly increased particularly in the presence of MgCl2 (Fig. 5B). SyDdh activity decreased to 42% in the presence of 2.5 mM oxamate, and the activities of SyDdh_Q14E and SyDdh_S234G were similarly inhibited (Fig. 5C). SyDdh activity decreased to 72% and 78% in the presence of 2.5 mM ATP and 2.5 mM iodoacetamide respectively, and the activities of SyDdh_Q14E and SyDdh_S234G were similarly decreased in the presence of ATP and iodoacetamide (Fig. 5C). Increased concentrations of MgCl2 enhanced the activation of SyDdh_Q14E; the activity was enhanced up to 140% of the activity of SyDdh_Q14E in the absence of MgCl2 (Fig. 6).

The k cat value of SyDdh for pyruvate in the presence of Mg2+ was 1.3 times that in the absence of Mg2+ (Tables 1 and 2). The S 0.5 value of SyDdh for pyruvate in the presence of Mg2+ increased from 0.38 to 0.59 mM in the presence of Mg2+ (Tables 1 and 2). In case of SyDdh_Q14E, the k cat value for pyruvate slightly decreased from 4.11 to 3.74 s−1; however, The S 0.5 value decreased to one-fourth that in the presence of Mg2+ (Tables 1 and 2). The k cat/S 0.5 value of SyDdh for pyruvate was reduced by Mg2+; on the contrary, that of SyDdh_Q14E markedly increased from 7.98 to 25.94 s−1 mM−1 (Tables 1 and 2).

Discussion

In this study, we performed a biochemical analysis of Ddh in the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis 6803 and demonstrated the substrate specificity and allosteric regulation of SyDdh, which were altered by amino acid substitutions (Tables 1 and 2).

The k cat value of SyDdh for pyruvate was lower than those of Ddhs from other bacteria (Table 1). The k cat values of Ddhs from other Gram-positive bacteria such as the lactic acid bacteria Pediococcus acidilactici, Lactobacillus pentosus, and Pediococcus pentosaceus are approximately 300 s−1 15,16,20, while the k cat value of Ddh from Bacillus coagulans was reported to be 23.6 s−1 21. The k cat values of Ddhs from the Gram-negative bacteria Fusobacterium nucleatum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are approximately 400 s−1, while that from E. coli is 80 s−1 14. Compared to these bacteria, the k cat value of SyDdh was low (2.7 s−1) (Table 1), demonstrating that Synechocystis 6803 possesses inefficient d-lactate dehydrogenase. This result is consistent with other studies on lactate production using Synechocystis 6803 that have been performed by introducing the external lactate dehydrogenase from the lactic acid bacteria Leuconostoc mesenteroides 18 or the mutated glycerol dehydrogenase from Bacillus coagulans 22. Other groups have also succeeded in producing lactate using cyanobacteria by mutating the lactate dehydrogenases so that they use NADPH, not NADH, as a cofactor23,24 or constructing another biosynthetic pathway than dihydroxyacetone phosphate25. These studies indicate that internal lactate dehydrogenases in cyanobacteria are inefficient enzymes in view of metabolic engineering. The S 0.5 value of SyDdh was similar to that of Fusobacterium nucleatum and lower than that of E. coli (Table 1)14, indicating that pyruvate affinity to SyDdh was similar or rather higher than that to other Ddhs in Gram-negative bacteria. Therefore, we here concluded based on biochemical evidence that SyDdh exhibited a lower k cat value compared to Ddhs from other bacteria, which was the reason for the inefficiency of SyDdh (Table 1).

Aside from pyruvate, SyDdh was able to use oxaloacetate as a substrate (Fig. S1 and Table 1). Ddhs from Fusobacterium nucleatum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa also showed affinity to oxaloacetate, and the affinities of these Ddhs to oxaloacetate are higher than that of Ddh from E. coli 14. We found that the serine residue at position 234 of SyDdh is important for substrate specificity (Table 1). The S 0.5 of SyDdh_S234G for pyruvate was 2.10 mM, which was 5.5 times of that of SyDdh (Table 1). On the contrary, the S 0.5 of SyDdh_S234G for oxaloacetate was 0.59 mM, which was approximately one-third of that of SyDdh (Table 1), indicating that the serine residue at position 234 of SyDdh increased the affinity to pyruvate and decreased the affinity to oxaloacetate. For lactic acid bacteria, the amino acid residues at positions 52 and 296 of Ddh are important for the affinity to pyruvate20,26. Combined with their data, we conclude that Ddhs contain substrate flexibility, which can be altered by amino acid substitutions. Our biochemical analysis suggested that SyDdh is able to catalyse the reaction from oxaloacetate to malate. Previously, a metabolic engineering study showed that the disruption of ddh in Synechocystis 6803 decreased the production of not only lactate but also succinate under dark, anaerobic conditions19. Metabolic flux analysis has shown that succinate is produced by the reductive tricarboxylic acid cycle in this cyanobacterium27, and thus, these results indicate that SyDdh potentially catalyses the reaction from oxaloacetate to malate under dark, anaerobic conditions.

The value of the Hill coefficient of SyDdh for pyruvate was 2.51 (Table 1), demonstrating that SyDdh exhibits positive homotropic cooperativity with pyruvate. The Hill coefficient of SyDdh is similar to Ddhs from Fusobacterium nucleatum and Escherichia coli 14, which is consistent with our phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 2). Ddhs from these Gram-negative bacteria form homo-tetramer (Table 3), and therefore, SyDdh was predicted to form homo-tetramer, although our Blue Native PAGE could not show the quaternary structure (Fig. S2B). The enzymatic activity in the presence of effectors also differed between SyDdh and Ddhs from other bacteria; SyDdh was activated by FBP but repressed by divalent cations (Fig. 5B). The amino acid substitution at positions 14 and 234 altered SyDdh so that it was activated by divalent cations (Fig. 5B). Similar to Ddhs from Fusobacterium nucleatum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa 14, SyDdh_Q14E was markedly activated by Mg2+ due to the increased affinity to pyruvate (Table 2). Mg2+ may bind more strongly to SyDdh_Q14E than to SyDdh because glutamate contains a negative charge. Ddhs from Gram-positive bacteria are also diverse; the activity of Ddh in the genus Pediococcus is altered by metal ions, while that in the genus Lactobacillus is not15,16,26,28. Thus, biochemical properties of Ddhs are diverse, and we have demonstrated the substrate specificity and allosteric regulation of SyDdh and identified amino acid residues that are important for the biochemical properties in this cyanobacterium.

Methods

Construction of the cloning vector and expression of recombinant proteins

The region of the Synechocystis 6803 genome containing the ddh (slr1556) ORF with the BamHI-XhoI fragment was commercially synthesised and cloned into the BamHI-XhoI site of pGEX5X-1 and pGEX6P-1 (GE Healthcare Japan, Tokyo, Japan) by Eurofins Genomics (Tokyo, Japan). Mutagenesis for amino acid substitution was performed by TakaraBio (Shiga, Japan). For SyDdh_Q14E and SyDdh_S234G, the regions +40–42 and +700–702 from the start codon in the ddh ORF were changed from CAA to GAA and AGT to GGT, respectively.

These vectors were transformed into E. coli DH5α (TakaraBio), and two litres of transformed E. coli were cultivated in LB media at 30°C with shaking (150 rpm), and expression of the protein was induced overnight in the presence of 0.01 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (Wako Chemicals, Osaka, Japan).

Affinity purification of recombinant proteins

Affinity chromatography for protein purification was performed as described previously29. Two litres of DH5α cells was disrupted by sonication (model VC-750, EYELA, Tokyo, Japan) for 3~4 min at 20% intensity, and the disrupted cells were centrifuged at 5,800 × g for 2 min at 4°C. All the supernatant was transferred to 50-mL tubes on ice, and 560 μL of Glutathione-Sepharose 4B resin (GE Healthcare Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was mixed into the supernatant, followed by gentle shaking for 30 min. Then, 1 mM ATP and 1 mM MgSO4·7H2O were added to the mixture, which was incubated with gentle shaking for 40 min to remove intracellular chaperons. After centrifugation (5,800 × g for 2 min at 4°C), the supernatant was removed, and the resins were re-suspended in 700 μL of PBS-T (1.37 M NaCl, 27 mM KCl, 81 mM Na2HPO4·12H2O, 14.7 mM KH2PO4, 0.05% Tween-20) with 1 mM ATP/1 mM MgSO4·7H2O. After washing with PBS-T 10 times, the recombinant proteins were eluted with 700 μL of GST elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM reduced glutathione) four times. The proteins were concentrated with a VivaSpin 500 MWCO 50000 device (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany), and the protein concentration was measured with a PIERCE BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). SDS-PAGE was performed to confirm protein purification with staining using InstantBlue (Expedion Protein Solutions, San Diego, CA). Proteases FactorXa and HRV 3C were purchased from Merck Millipore (Darmstadt, Germany) and TakaraBio, respectively. Blue Native PAGE was performed by applying the samples, each 9.4 μg of purified SyDdh proteins with 0.5% Brilliant Blue G (TCI, Tokyo, Japan), to NativePAGE™ 4–16% Bis-Tris Protein Gels (Thermo Scientific). Cathode buffer (50 mM Tricine-NaOH, 15 mM Bis-Tris/HCl, pH 7.0, 0.02% Brilliant Blue G) and anode buffer (50 mM Bis-Tris/HCl, pH 7.0) was used for electrophoresis. The gel was stained using InstantBlue after electrophoresis.

Enzyme assay

Ddh activity was measured using 60 pmol of SyDdhs mixed in a 1 mL assay solution [100 mM potassium phosphate, 0.1 mM nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydride (NADH), 1 mM sodium pyruvate]. The absorbance at A 340 was monitored using a Hitachi U-3310 spectrophotometer (Hitachi High-Tech., Tokyo, Japan). The kinetic parameters of Ddhs were calculated by curve fitting using Kaleida Graph ver. 4.5 software. When the data exhibited substrate inhibition, we used equation 1 30. When the data exhibited cooperativity with a substrate, we used the Hill equation (equation 2)31. When the data showed neither substrate inhibition nor cooperativity, we used the Michaelis-Menten equation (equation 3).

v and V max indicate reaction velocity and maximum reaction velocity, respectively. [S] indicates substrate concentration, and S 0.5 indicates the half-maximum concentration giving rise to 50% V max. K i is an inhibition constant, and n H is the Hill coefficient. One unit of SyDdh activity was defined as the consumption of 1 μmol NADH per minute.

In silico modelling

Homology modelling of SyDdh was performed with a database SWISS-MODEL (https://www.swissmodel.expasy.org/) using amino acid sequence of SyDdh from GenBank (Protein ID BAA18694.1) as a query. Ddh from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (PDB ID: 3WWZ) was used as a template. 3D structures were visualized using a PyMOL software (v1.7.4, Schrödinger).

References

Ostafinska, A. et al. Strong synergistic effects in PLA/PCL blends: Impact of PLA matrix viscosity. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 69, 229–241, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.01.015 (2017).

Li, X. et al. In vitro degradation kinetics of pure PLA and Mg/PLA composite: Effects of immersion temperature and compression stress. Acta Biomater. 48, 468–478, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2016.11.001 (2017).

Tsuji, H. Poly(lactide) stereocomplexes: formation, structure, properties, degradation, and applications. Macromol. Biosci. 5, 569–597 (2005).

Tsuji, H., Takai, H. & Saha, S. K. Isothermal and non-isothermal crystallization behavior of poly(l-lactic acid): Effects of stereocomplex as nucleating agent. Polymer. 47, 3826–3837 (2006).

Mazzoli, R., Bosco, F., Mizrahi, I., Bayer, E. A. & Pessione, E. Towards lactic acid bacteria-based biorefineries. Biotechnol Adv. 32, 1216–1236 (2014).

Poudel, P., Tashiro, Y. & Sakai, K. New application of Bacillus strains for optically pure L-lactic acid production: general overview and future prospects. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 80, 642–654 (2016).

Juturu, V. & Wu, J. C. Microbial production of lactic acid: the latest development. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 36, 967–977 (2016).

Zhang, J., Gong, G., Wang, X., Zhang, H. & Tian, W. Positive selection on d-lactate dehydrogenases of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subspecies bulgaricus. IET Syst Biol. 9, 172–179, https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-syb.2014.0056 (2015).

Zhu, L., Xu, X., Wang, L., Dong, H. & Yu, B. The d-lactate dehydrogenase from Sporolactobacillus inulinus also possessing reversible deamination activity. PLoS One. 10, e0139066, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139066 (2015).

Meng, H. et al. Engineering a d-lactate dehydrogenase that can super-efficiently utilize NADPH and NADH as cofactors. Sci Rep. 6, 24887, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24887 (2016).

Taguchi, H. & Ohta, T. d-lactate dehydrogenase is a member of the d-isomer-specific 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase family. Cloning, sequencing, and expression in Escherichia coli of the d-lactate dehydrogenase gene of Lactobacillus plantarum. J Biol Chem. 266, 12588–12594 (1991).

Arai, K. et al. Active and inactive state structures of unliganded Lactobacillus casei allosteric l-lactate dehydrogenase. Proteins. 78, 681–694, https://doi.org/10.1002/prot.22597 (2010).

Matoba, Y. et al. An alternative allosteric regulation mechanism of an acidophilic l-lactate dehydrogenase from Enterococcus mundtii 15-1A. FEBS Open Bio. 4, 834–847, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fob.2014.08.006 (2014).

Furukawa, N., Miyanaga, A., Togawa, M., Nakajima, M. & Taguchi, H. Diverse allosteric and catalytic functions of tetrameric d-lactate dehydrogenases from three Gram-negative bacteria. AMB Express. 4, 76, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-014-0076-1 (2014).

Mu, W., Yu, S., Jiang, B. & Li, X. Characterization of d-lactate dehydrogenase from Pediococcus acidilactici that converts phenylpyruvic acid into phenyllactic acid. Biotechnol Lett. 34, 907–911, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-012-0847-1 (2012).

Yu, S., Jiang, H., Jiang, B. & Mu, W. Characterization of d-lactate dehydrogenase producing d-3-phenyllactic acid from Pediococcus pentosaceus. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 76, 853–855 (2012).

Kanesaki, Y. et al. Identification of substrain-specific mutations by massively parallel whole-genome resequencing of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 19, 67–79 (2012).

Angermayr, S. A. et al. Chirality matters: synthesis and consumption of the d-enantiomer of lactic acid by Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 1295–1304 (2015).

Osanai, T. et al. Genetic manipulation of a metabolic enzyme and a transcriptional regulator increasing succinate excretion from unicellular cyanobacterium. Front Microbiol. 6, 1064, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01064 (2015).

Tokuda, C. et al. Conversion of Lactobacillus pentosus d-lactate dehydrogenase to a d-hydroxyisocaproate dehydrogenase through a single amino acid replacement. J Bacteriol. 185, 5023–5026 (2003).

Zheng, Z. et al. Efficient conversion of phenylpyruvic acid to phenyllactic acid by using whole cells of Bacillus coagulans SDM. PLoS One. 6, e19030, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019030 (2011).

Varman, A. M., Yu, Y., You, L. & Tang, Y. J. Photoautotrophic production of d-lactic acid in an engineered cyanobacterium. Microbial Cell fact. 12, 117 (2013).

Angermayr, S. A. et al. Exploring metabolic engineering design principles for the photosynthetic production of lactic acid by Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Biotechnol. Biofuels 7, 99 (2014).

Li, C. et al. Enhancing the light-driven production of d-lactate by engineering cyanobacterium using a combinational strategy. Sci. Rep. 5, 9777 (2015).

Hirokawa Y., Goto R., Umetani Y., & Hanai T. Construction of a novel d-lactate producing pathway from dihydroxyacetone phosphate of the Calvin cycle in cyanobacterium, Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. J. Biosci. Bioeng. (2017) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2017.02.016.

Taguchi, H. & Ohta, T. Histidine 296 is essential for the catalysis in Lactobacillus plantarum d-lactate dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 268, 18030–18034 (1993).

Hasunuma, T., Matsuda, M. & Kondo, A. Improved sugar-free succinate production by Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 following identification of the limiting steps in glycogen catabolism. Metab. Eng. Commun. 3, 130–141 (2016).

Kochhar, S., Hunziker, P. E., Leong-Morgenthaler, P. & Hottinger, H. Primary structure, physicochemical properties, and chemical modification of NAD(+)-dependent D-lactate dehydrogenase. Evidence for the presence of Arg-235, His-303, Tyr-101, and Trp-19 at or near the active site. J Biol Chem. 267, 8499–8513 (1992).

Takeya, M., Hirai, M. Y. & Osanai, T. Allosteric inhibition of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylases is determined by a single amino acid residue in cyanobacteria. Sci Rep. 7, 41080, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41080 (2017).

Eszes, C. M., Sessions, R. B., Clarke, A. R., Moreton, K. M. & Holbrook, J. J. Removal of substrate inhibition in a lactate dehydrogenase from human muscle by a single residue change. FEBS Lett. 399, 193–197 (1996).

Dixon, M., & Webb, E. C. Enzymes. Longman, London, pp 400–402 (1979).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan, by a grant to T.O. from ALCA (Project name “Production of cyanobacterial succinate by the genetic engineering of transcriptional regulators and circadian clocks”) from the Japan Science and Technology Agency and by JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas, Grant Number 16H06559.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.I. and M.T. designed the research, performed the experiments, analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. T.O. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ito, S., Takeya, M. & Osanai, T. Substrate Specificity and Allosteric Regulation of a d-Lactate Dehydrogenase from a Unicellular Cyanobacterium are Altered by an Amino Acid Substitution. Sci Rep 7, 15052 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15341-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15341-5

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.