Abstract

The sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP, SLC10A1) is the main hepatic transporter of conjugated bile acids, and the entry receptor for hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis delta virus (HDV). Myrcludex B, a synthetic peptide mimicking the NTCP-binding domain of HBV, effectively blocks HBV and HDV infection. In addition, Myrcludex B inhibits NTCP-mediated bile acid uptake, suggesting that also other NTCP inhibitors could potentially be a novel treatment of HBV/HDV infection. This study aims to identify clinically-applied compounds intervening with NTCP-mediated bile acid transport and HBV/HDV infection. 1280 FDA/EMA-approved drugs were screened to identify compounds that reduce uptake of taurocholic acid and lower Myrcludex B-binding in U2OS cells stably expressing human NTCP. HBV/HDV viral entry inhibition was studied in HepaRG cells. The four most potent inhibitors of human NTCP were rosiglitazone (IC50 5.1 µM), zafirlukast (IC50 6.5 µM), TRIAC (IC50 6.9 µM), and sulfasalazine (IC50 9.6 µM). Chicago sky blue 6B (IC50 7.1 µM) inhibited both NTCP and ASBT, a distinct though related bile acid transporter. Rosiglitazone, zafirlukast, TRIAC, sulfasalazine, and chicago sky blue 6B reduced HBV/HDV infection in HepaRG cells in a dose-dependent manner. Five out of 1280 clinically approved drugs were identified that inhibit NTCP-mediated bile acid uptake and HBV/HDV infection in vitro.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP, SLC10A1) plays a pivotal role in the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids as the main uptake transporter of conjugated bile acids in the liver1. NTCP is exclusively expressed at the basolateral membrane of hepatocytes, where it extracts bile acids from the portal vein in a sodium-dependent manner. Recently, NTCP was identified as the entry receptor for the hepatitis B virus (HBV)2,3. Viral infection with Hepatitis B causes acute and chronic inflammation of the liver and is one of the major infectious diseases worldwide4. Chronic HBV infection is nowadays treated by interferon-alpha or nucleoside/nucleotide analogues but this rarely results in viral elimination. On top of HBV infection, it is estimated that 5% of HBV patients suffer from a co- or superinfection of the related hepatitis delta virus (HDV)5,6,7. This RNA virus propagates only in HBV infected cells as HBV-encoded envelope proteins are utilized for HDV envelopment. For HDV no antiviral treatment is available. Furthermore, recent data show that NTCP also plays a modulatory role in hepatitis C virus (HCV) host cell infection and cell to cell transmission by bile-acid-mediated regulation of antiviral responses of the innate immune system8.

HBV/HDV binding to the NTCP protein on the host cell is mediated by the myristoylated preS1-domain of the HBV envelope L-protein9. Myrcludex B, a synthetic peptide mimicking the HBV-specific NTCP-binding domain10, strongly interferes with viral docking and therefore abrogates HBV/HDV infection in established cell culture models of HBV/HDV infection11,12. Currently, Myrcludex B is being tested in phase II clinical trials as a novel means to inhibit HBV/HDV entry13,14,15,16. Largely reduced HDV RNA and HBV DNA serum levels were detected in a cohort of chronic hepatitis delta patients treated with Myrcludex B for 24 weeks13.

Upon NTCP inhibition by Myrcludex B, bile acid transport is affected17. However, whether NTCP inhibition can also affect drug exposure or clearance is unknown. Therefore we formulated the following three research questions. First, can we identify clinically applied and licenced drugs as novel NTCP inhibitors? Second, and in the context of drug-drug interaction, do such drugs compete with Myrcludex B for NTCP and vice versa? Third, can these novel NTCP inhibitors reduce HBV/HDV infection in vitro? In two screening approaches we evaluated 1280 clinically approved drugs on interference with NTCP-mediated bile acid transport and on occupation of the Myrcludex B binding site of NTCP. As a result, we describe the identification of 5 novel NTCP inhibitors with an estimated IC50 value below 10 µM that reduce HBV/HDV infection in HepaRG cells in a dose-dependent manner.

Results

Identification of novel NTCP inhibitors

To find novel NTCP inhibitors, 1280 drugs were screened at a concentration of 10 µM (Fig. 1A). Therefore, two screening strategies using U2OS cells stably transfected with human NTCP were combined. Since U2OS cells do not express endogenous bile acid transporter proteins NTCP-independent taurocholate uptake activity is minimal18,19. Screening quality was assessed by defining the z-factor for each screening plate20, continuing data analysis for plates of a z-factor between 0.5–1.0. NTCP inhibition was acknowledged to a drug if taurocholate uptake or Myrcludex B-FITC fluorescence was decreased with at least 75% compared to the control. For each compound two B scores were calculated (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table S1), which is a statistical score that shows the relative potency of a candidate within the studied population21. Amongst the top 150 hits, our screen identified bile acids (litocholic acid, chenodeoxycholic acid, ursodeoxycholic acid) (Fig. 1B, green dots) and drugs that had been described earlier as NTCP inhibitors (cyclosporin A, irbesartan, ezetimibe, pioglitazone22,23,24,25,26) (Fig. 1B, blue dots), which provided validation of both screening methods. From the top 30 we selected our hits, but we excluded bile acids and previously described NTCP inhibitors, as well as compounds inducing apoptosis or described as being hepatotoxic. We further narrowed down the remaining list of compounds by selecting one drug from a cluster of two or more drugs with a similar structure and/or mechanistic action, e.g. zafirlukast, pranlukast and montelukast. This resulted in a total of ten candidates selected from the lower-left quadrant for follow-up analysis: chicago sky blue 6B, flufenamic acid, nelfinavir mesylate hydrate, nifedipine, rosiglitazone, sulfasalazine, tolfenamic acid, toltrazuril, TRIAC, and zafirlukast (Fig. 1B red dots). Additionally, two compounds were selected that were only identified in one of the two screens: amlexanox (TC uptake screen) and hydroxytacrine maleate (Myrcludex B binding assay). Follow-up screening proved them to be false positives, demonstrating the effectiveness of using overlapping data from two different/orthogonal assays for compound selection.

Screening approach and results. (A) Flow diagram of the approach to identify drugs that inhibit human NTCP. (B) B-scores for each compound of the two screening assays are depicted with inhibition of uptake present in the lower quadrants and inhibition of Myrcludex B binding in the left quadrants. Each dot represents a compound, with bile acids in green, previously known NTCP-inhibitors in blue, and the compounds selected for further analysis in red.

In vitro validation of selected overlapping top-hits

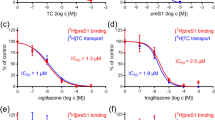

Five out of twelve selected compounds inhibited NTCP in repeated measurements of TC-uptake and Myrcludex B binding at concentrations of ≤ 10 µM: chicago sky blue 6B, rosiglitazone, sulfasalazine, TRIAC, and zafirlukast (Table 1). Inhibition was measured and IC50 values were calculated from increasing concentrations, ranging from 1 nM to 10 mM. Zafirlukast was one of the most potent inhibitors with an IC50 value of 6.5 µM (Fig. 2A and B) and more than 50% decreased Myrcludex B binding at 10 µM (Fig. 2C and D). Figure 3 shows the inhibitory effects of chicago sky blue 6B, rosiglitazone, sulfasalazine, and TRIAC on NTCP-mediated TC uptake and Mycludex B binding. Flufenamic acid and tolfenamic acid had an IC50 value of 10 and 12.5 µM respectively, and both decreased Myrcludex B binding to NTCP with 50% at ≤ 100 µM. Selected compounds with lower affinity were not included in further experiments (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2).

Inhibition of human NTCP by zafirlukast. (A) Taurocholate uptake into U2OS-HA-hNTCP cells was reduced in the presence of zafirlukast in a concentration-dependent fashion. (B) After normalization to maximal NTCP inhibition, the IC50 value was calculated. N = 2–4 wells/condition, experiment was repeated twice. (C) Representative confocal microscopy pictures of reduced Myrcludex B-FITC fluorescence upon co-administration with increasing amounts of zafirlukast. (D) Quantification of C, n = 3 per condition. All data are presented as mean ± SD.

Inhibition of human NTCP by chicago sky blue 6B, rosiglitazone, sulfasalazine, and TRIAC. Taurocholate uptake and Myrcludex B binding was reduced to U2OS-HA-hNTCP cells in a concentration-dependent manner by chicago sky blue 6B (A,B), rosiglitazone (C,D), sulfasalazine (E,F), and TRIAC (G,H). Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 2–4 wells/condition, experiment was repeated twice. From the confocal studies, representative pictures are shown, n = 3 per condition.

Myrcludex B inhibits uptake of tauro-ursodeoxycholic acid

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), an unconjugated bile acid frequently used as treatment in cholestatic conditions, was found among the top 100 best hits (Supplementary Table S1). Indeed, sodium-dependent uptake of tauro-ursodeoxycholic acid is largely inhibited upon treatment with Myrcludex B (Fig. 4) as described before for taurocholic acid (IC50 52,5 nM)24. This indicates that therapeutic co-administration of Myrcludex B at NTCP saturating conditions with UDCA might affect the pharmacokinetics of UDCA and vice versa. Of note, Myrcludex B effectively inhibits HBV/HDV infection at concentrations (83 pM for HBeAg in primary human hepatocytes24), where NTCP-mediated transport of substrates is not yet affected. From the other compounds that reduced NTCP activity (b-score ≤−5) frequent clinical co-application with Myrcludex B, and thus possibly drug-drug interaction, is not anticipated.

Drug cytotoxicity

Drug cytotoxicity was examined for each compound at three concentrations. In U2OS-HA-hNTCP cells, viability was above 80% for all drugs at the two lowest concentrations (Supplementary Table S2). At 100 µM, nifedipine and zafirlukast exerted minor cytotoxicity, with a cell viability of 71.5 ± 7.3% and 77.7 ± 8.0% respectively. Similar cell viability results were obtained in U2OS-HA-hNTCP and in wildtype U2OS cells (Supplementary Table S2).

Inhibition of HBV and HDV infection

Since several NTCP inhibitors, e.g. irbesartan and cyclosporin A, have been shown to affect HBV and HDV infection22,23,24,25,27, we tested the 5 strongest hits from our screen in this experimental setting as well for interference with HBV/HDV infection. To that aim HepaRG cells were infected with HBV or HDV and viral markers HBsAg, HBeAg and intracellular HBcAg/HDAg were quantified. Myrcludex B and irbesartan were included as positive controls for infection inhibition. As depicted in Fig. 5A and B, production of both HBeAg and HBsAg was significantly reduced for all compounds in a concentration-dependent manner. Zafirlukast, chicago sky blue 6B and irbesartan were effective at 17 µM, whereas rosiglitazone, sulfasalazine, and TRIAC which were only effective in reducing HBsAg at concentrations of ≥50 µM. Higher concentrations of the drugs established a further reduction in HBeAg and HBsAg. Immunofluorescence data of hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) stained HepaRG cells at day 10 post HBV infection (Fig. 5C and D) corresponded to these findings: the number of positive stained cells was severely reduced by addition of 50 µM chicago sky blue 6B, rosiglitazone, or zafirlukast. At similar concentrations, sulfasalazine and TRIAC only induced a mild reduction in positive stained cells. For HDV infection, similar results were obtained (Fig. 5E and F). To address whether the inhibitory effect was limited to a specific HBV genotype or cell-derived virus we tested the effect of sulfasalazine using patient-derived HBV (genotype B), which was also from a different genotype than the cell derived HBV (genotype D). Sulfasalazine showed similar inhibitory effects on HBeAg and HBsAg levels for serum-derived HBV as for cell-derived HBV (Supplementary Figure S3), demonstrating that the inhibitory effects on infection were not limited to the source or genotype of HBV.

Inhibition of HBV and HDV infection in HepaRG cells. Rosiglitazone, sulfasalazine, TRIAC, zafirlukast, and irbesartan reduce both HBV (A–D) as well as HDV (E,F) infection in HepaRG cells. In a concentration-dependent fashion, hepatitis B extracellulair (A) and surface (B) antigen production was reduced by all compounds. Also, all compounds were effective in decreasing the amount of cells positively stained for HBcAg (C,D) and HDAg (E,F) in a concentration-dependent manner. Myrcludex B (1 µM) was included as positive control in all assays. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3 × 2 wells/condition.

Specificity for NTCP

At the calculated IC50 value for hNTCP, chicago sky blue 6B, flufenamic acid, and rosiglitazone were more capable of inhibiting mouse Ntcp (Fig. 6A–C), while sulfasalazine, tolfenamic acid and zafirlukast were able to inhibit mouse Ntcp to a similar extent as human NTCP (Fig. 6D,E and G). TRIAC inhibited NTCP-mediated bile acid transport at lower concentrations for human NTCP than for mouse Ntcp (Fig. 6F).

Compounds also inhibit mouse NTCP. (A–G) Taurocholate uptake into U2OS cells transiently transfected with mouse NTCP is inhibited similarly as human NTCP by sulfasalazine (D), tolfenamic acid (E) and zafirlukast (G), while chicago sky blue 6B (A), flufenamic acid (B), and rosiglitazone (C) are more potent in inhibiting mouse NTCP. TRIAC on the other hand inhibits human NTCP more strongly (F). Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 2–4 wells/condition.

The apical sodium bile acid transporter (ASBT, SLC10a2), most highly expressed at the brush border of ileal enterocytes28, is a closely related transporter showing highest sequence similarity with NTCP1. Both NTCP and ASBT mediate cellular uptake of conjugated bile acids. Therefore, we examined whether the 5 most potent NTCP inhibitors also affected ASBT-mediated bile acid transport. Both chicago sky blue 6B and TRIAC inhibited ASBT to a similar extent as NTCP with a comparable decrease in taurocholate uptake at all tested concentrations (Fig. 7A and D). Complete absence of ASBT inhibition was shown for sulfasalazine (Fig. 7C), while rosiglitazone and zafirlukast inhibited ASBT less effectively and at higher concentrations than observed for NTCP (Fig. 7B and E).

Some NTCP inhibitors also reduce ASBT-mediated bile acid uptake. (A–E) Sulfasalazine (C) is largely ineffective in inhibiting taurocholate uptake into MDCK-ASBT cells, while chicago sky blue 6B (A), rosiglitazone (B), TRIAC (D), and zafirlukast (E) inhibit ASBT in a concentration-dependent fashion. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 2–3 wells/condition.

Discussion

From 1280 clinically-applied drugs, this study identified 5 novel NTCP inhibitors that also block HBV and HDV infection in vitro. Until the recent identification of compounds that directly act on the viral large surface protein29, most HBV/HDV entry blockers identified to date inhibit both NTCP-mediated bile acid uptake as well as infection. Partially, this is explained by historical reasons as the inhibitory effect of compounds like cyclosporine22,24, ezetimibe23 and irbesartan23,25 on HBV infection was assessed when the receptor NTCP was identified and their effect on taurocholate uptake has already been known. However, the finding that also Myrcludex B, a peptide mimicking the myristoylated preS1-domain of the HBV envelope L-protein, interfered with NTCP-mediated bile acid uptake supported the notion that the HBV and bile acid binding sites in the NTCP protein are in close proximity and/or functionally intertwined3. In this study, the effects of 1280 clinically-applied compounds on both bile acid uptake and Myrcludex B binding were directly compared in an unbiased manner.

The screen confirmed NTCP inhibition by cyclosporin A, irbesartan, ezetimibe, and pioglitazone which had previously been identified as such22,23,24,25,26, and underscores the likelihood of a correlation between blocked bile acid transport and occupation of the HBV-binding site on NTCP. Reduced HBV/HDV infection in vitro was demonstrated for chicago sky blue 6B, rosiglitazone, sulfasalazine, TRIAC, and zafirlukast. In well-established HBV/HDV infection systems, these 5 novel inhibitors mainly act by targeting NTCP as the viral entry receptor. This is supported by the following two findings: 1) HDV infection was similarly affected as HBV infection. Both viruses share early infection events but follow different routes in viral replication5,6. 2) Cellular binding of Myrcludex B, the myristoylated preS1-domain of the HBV envelope L-protein9, was decreased upon co-administration with the 5 novel inhibitors, suggesting competition for the HBV binding site on the NTCP protein.

For these 5 compounds, bile acid transport is largely inhibited at a similar concentration needed to block HBV/HDV infection (IC50: 5–10 µM). On the contrary, Myrcludex B has an IC50 value for bile acid transport of 52.5 nM in primary human hepatocytes24, but blocks HBV infection at an at least 50-fold lower concentration (669 pM for HBsAg/83 pM for HBeAg), leaving a sufficient therapeutic range in which Myrcludex B efficiently blocks HBV/HDV infection while bile acid transport is largely unaffected. Another class of small molecules, proanthocyanidin and its analogues, were also shown to inhibit the HBV viral entry process with unaffected NTCP-mediated bile acid transport29. Proanthocyanidin directly targets the PreS1 region of the HBV L-protein, forming a novel class of anti-HBV agents.

The identification of 5 diverse novel NTCP inhibitors (chicago sky blue 6B, rosiglitazone, sulfasalazine, TRIAC, and zafirlukast) expands the chemical backbones to build new, more specific small molecule HBV/HDV entry inhibitors. Recently, cyclosporin A derivatives were developed that reduced NTCP-mediated HBV infection in primary hepatocytes by ~60% without significantly reducing bile acid uptake30. This suggests that analogues of rosiglitazone, sulfasalazine, zafirlukast and perhaps TRIAC could possibly be designed that more potently and specifically inhibit HBV infection. From the cheminformatics analysis limits for this chemical space can be established (Supplementary Figs S4 and S5). As ligands with a molecular weight <300 and AlogP of 3 or lower were identified, one could speculate that these ligands inhibit NTCP in a manner other than competitive inhibition of the bile acid binding site. Our virtual screening could not reliably identify novel active compounds. Unlike other bile acid transporters like OATPs, NTCP is likely not addressed by most chemotypes, as the percentage of actives identified in this study is much lower than in a similar screen for OATP inhibitors (respectively ~1% versus 7–10%)31. Previous computational models further support this observation23,25,26,32,33. Although they all could elucidate the requirement of hydrophobes and hydrogen bond acceptors, the exact number for these features varied between 3 and 1 for both in line with the current work23,26,32,33. Furthermore, Kramer et al.34 concluded that substrate specificity is much broader for NTCP than for the related bile acid transporter ASBT. Indeed, sulfasalazine, rosiglitazone, and zafirlukast, are more selective for NTCP, while chicago sky blue 6B and TRIAC were as effective for ASBT as for NTCP. Chicago sky blue 6B was also identified as an inhibitor for vesicular glutamate transporters (VGLUTs), completely unrelated transporters, further demonstrating its low specificity35. Although species-specific differences have been found for drugs bosentan36 and rosuvastatin37, only minor differences in drug specificity between mouse and human NTCP were found for sulfasalazine, rosiglitazone, and zafirlukast.

The usage of clinically-relevant compounds in a screen for NTCP inhibitors provides additional information as it seems likely that several of the hits are NTCP substrates. Myrcludex B could possibly be used in combination with such drugs, potentially leading to drug-drug interactions. In this respect, predominantly ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) should be considered. UDCA is an unconjugated bile acid frequently used as treatment in cholestatic conditions, mainly primary biliary cholangitis38. Upon administration, all UDCA is converted to its glycine and taurine conjugated forms which mediate its hepatoprotective effects39. This therapeutic bile acid was found amongst the top 100 hits and Myrcludex B largely inhibited NTCP-dependent uptake of tauro-UDCA. This suggests that Myrcludex B co-administration might affect clearance and exposure of (conjugated) UDCA at dosages that interfere with the transporter function of NTCP, which are higher than the dose required for lowering HBV/HDV infection.

Supplementary Table S4 describes expected serum levels of sulfasalazine, rosiglitazone, TRIAC, and zafirlukast upon normal therapeutic use for their intended diseases40,41,42,43,44. With their IC50 for NTCP in mind, sulfasalazine, rosiglitazone, and TRIAC are relevant to be considered as NTCP inhibitors upon normal therapeutic use, while treatment with zafirlukast is unlikely to induce NTCP inhibition. Notably, sulfasalazine has previously been shown to be a potent inhibitor of glycochenodeoxycholic acid (GCDCA)- induced apoptosis in hepatocytes in vitro and in the intact liver independently of its inhibiting effects on hepatocellular GCDCA uptake50, making it even more attractive as a candidate for therapeutic NTCP inhibition. In conclusion, from a library of clinically-applied drugs various compounds were identified that inhibit NTCP-mediated bile acid uptake and HBV/HDV infection in vitro. These findings could contribute to the development of novel anti-HBV and HDV agents.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

The Prestwick Chemical Library® containing 1280 approved drugs as 10 mM stock solutions in 96-well plates was purchased from Prestwick (Prestwick Chemical, Illkirch, France). Amlexanox was purchased from Abcam. Hydroxytacrine Maleate was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, USA). Chicago Sky Blue 6B, Flufenamic acid, Nelfinavir Mesylate Hydrate, Nifedipine, Rosiglitazone, Sulfasalazine, Tolfenamic acid, Toltrazuril, 3,3′,5-Triiodothyroacetic acid (TRIAC), Zafirlukast, and Taurocholic acid (TC) were bought from Sigma-Aldrich (Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands). Myrcludex B and Myrcludex B-FITC were customly synthesized by Pepscan (Lelystad, The Netherlands). Hoechst 33342 was obtained from Merck Millipore (Darmstadt, Germany). [3H]Taurocholic acid (1 mCi/ml) and [14C]Taurocholic acid (0.05 mCi/ml) were purchased from PerkinElmer (Groningen, The Netherlands).

Cell culture

U2OS and MDCK cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Sigma-Aldrich), supplemented with 10% FCS (Gibco), 1% L-glutamine (Lonza), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Lonza). Medium of U2OS cells stably transfected with human NTCP (U2OS-HA-hNTCP)18 or MDCK cells stably expressing human ASBT (MDCK-hASBT; kind gift of Paul Dawson)45 was supplemented with 400 µg/ml or 350 µg/ml Geneticin (Invitrogen) respectively. Transient transfection of U2OS cells with mouse NTCP (mNTCP) was done with PEI reagent (Brunschwig, Basel, Switzerland). Shortly, U2OS cells were seeded one day prior to transfection in 24-well plates. On the day of transfection, 0.5 µg DNA was mixed with 100 µl unsupplemented DMEM and 3 µg/µl PEI. After 10–15 minute incubation at RT, 20 µl of the transfection mix was added to each 24-well. Transfected cells were used in further experiments 48–72 hours later. Cell lines were passaged twice a week at a confluence of 80%, and incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 37 °C + 5% CO2.

HepaRG cells were cultured in Williams E medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 5 µg/ml insulin, 50 µM hydrocortisone, 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 µg/ml streptomycin. After two weeks of cultivation, differentiation was induced by 1.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as described11.

Screening studies

We screened the Prestwick Chemical Library® in 96-well format using two different screening assays: a taurocholate uptake assay (using PerkinElmer ViewPlate-96 white microplate clear bottom, product number 6005181) and a competitive binding assay (using PerkinElmer CellCarrier-96 black, product number 6005550). Plates were seeded with U2OS-HA-hNTCP (92 wells) or U2OS (4 wells, background) cells at a density of 50.000 cells/well or 10.000 cells/well for the functional or the competitive binding assay respectively. Screening assays were performed at room temperature approximately 24 hours later. Drug concentration was 10 µM and 1 µM Myrcludex B was used as positive control for NTCP inhibition and binding.

For the taurocholate uptake studies, medium was aspirated and cells were washed once with 100 µL uptake buffer: 5 mM KCl, 1.1 mM K2HPO4, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 10 mM D-Glucose, 10 mM HEPES and 136 mM NaCl. For sodium free uptake buffer, NaCl was replaced by 136 mM NMDG. Buffers were set to pH 7.4, at room temperature. After washing, cells were pre-incubated for 10 minutes with drugs in 50 µL uptake buffer. Subsequently, 50 µL uptake buffer containing [14C]taurocholate was added to the wells for another 10 minutes. After incubation, buffer was removed and cells were washed 2x with ice-cold PBS. Cells were lysed for a minimum of 30 minutes in 30 µL/well 0.05% SDS in water. When lysis was complete, 120 µL MicroScint™-20 (PerkinElmer) was added to the wells and radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation counting.

For the fluorescent binding assay, medium was aspirated and cells were washed once with 100 µL PBS. A 30 minute incubation period followed in which all cells were incubated with 0.2 µM Myrcludex B-FITC with or without drug in 100 µL Leibovitz’s L-15 Medium (Invitrogen). Cells were washed twice with PBS and subsequently 100 µL Leibovitz’s L-15 Medium was added. Of each well, 9 photos (10x objective) were taken in the brightfield and FITC channel using the Operetta CLS™ High-Content Imaging System (PerkinElmer).

Inhibition studies

Wildtype U2OS or U2OS-HA-hNTCP were seeded at a density of 50.000 cells in 500 µL complete medium in 24-well plates (VWR® Cat. Number 734–2325). For MDCK or MDCK-hASBT cells 70.000 cells/well were plated in 24-well plates, followed by 24 hours 10 mM sodium butyrate (Sigma-Aldrich) stimulation the next day. Cells were used in the inhibition studies 24 hours (U2OS cell lines) or 48 hours (MDCK cell lines) later. Inhibition studies with mNTCP transiently transfected cells were conducted 48–72 hours after transfection.

Medium was aspirated from the wells and cells were washed once with 250 µL uptake buffer. Subsequently, cells were pre-incubated with drug in 150 µL uptake buffer for 10 minutes at 37 °C. Taurocholate uptake was initiated by addition of 100 µL uptake buffer containing taurocholate (final concentration 10 µM TC spiked with tritium-labeled TC) and cells were incubated for 2 minutes at 37 °C. Subsequently, cells were washed 4 times with ice-cold PBS and lysed with 0.05% SDS in water. Radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation counting.

Confocal microscopy

Wildtype U2OS or U2OS-HA-hNTCP were seeded in a sterile 8-well coverslip bottomed chamber slide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 155411). After 24 hours, medium was aspirated and cells were washed once with 300 µl Leibovitz’s L-15 Medium (Invitrogen). A 30 minute incubation period followed in which all cells were incubated with 0.2 µM Myrcludex B-FITC with or without drug (1, 10, 100 µM) and Hoechst (1/1000) in 300 µL Leibovitz’s L-15 Medium. Cells were washed twice with Leibovitz’s L-15 Medium and subsequently 400 µL Leibovitz’s L-15 Medium was added. Live cell fluorescent imaging was performed using a Leica SP8X-SMD confocal microscope with fully enclosed incubation at 37 °C. A 63x oil objective was used and images were captured while the cells were consecutively excited at 490 nm (FITC) 350 nm (Hoechst). ImageJ software (National Insititutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was employed for data analysis.

Cytotoxicity studies

Drug cytotoxicity was evaluated by measuring the cell viability using the water soluble tetrazolium salt WST-1 (Sigma-Aldrich). Shortly, U2OS-HA-hNTCP cells were seeded at a density of 10.000 cells/well in 96-well plates (Corning® Costar® Cat. Number 3595), and incubated for approximately 24 hours at 37 °C + 5% CO2. Medium was aspirated and cells were exposed to 1 µM, 10 µM, or 100 µM drug in 100 µL complete medium. Empty wells containing only complete medium served as background. In addition, each well was supplemented with 10 µL WST-1. After two hours incubation (37 °C + 5% CO2), absorbance at 450 nm and 690 nm was measured using a Synergy HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Biotek). Cell viability was calculated using the following formula: (A450-A690 (sample)) − (A450-A690 (background)). Viability levels higher than 80% were considered healthy and unaffected by the drug.

HBV/HDV infection studies

HBV was produced in HepAD38 cells46. HDV was produced by co-transfection of HuH7 cells with the two plasmids pSVLD3 (HDV genotype 1, kindly provided by John Taylor47) and pT7HB2.7 (HBV genotype D, kindly provided by Camille Sureau48). Virions in the culture supernatant were purified and concentrated by heparin affinity chromatography on an ÄKTApurifier FPLC system (GE Healthcare) and stored at −80 °C in 10% FCS.

Cells were pre-incubated for 30 min with NTCP inhibitors or Myrcludex B in medium containing 4% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1.5% DMSO. They were then inoculated with HBV or HDV for 14 h at 37 °C. After inoculation, cells were washed twice with PBS and post-incubated with NTCP inhibitors or Myrcludex B. After 10 hours, the cells were washed twice in PBS before medium supplemented with 1.5% DMSO was added. Medium was exchanged every 2 days. Cells infected with HDV were fixed on day 5 post infection and HDV infection was quantified by immunofluorescence. To quantify the HBV infection, secretion of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis B extracellular antigen (HBeAg) into the culture supernatant from day 7 to 10 post infection was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The cells were fixed 10 days post infection and analysed by hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) specific immunofluorescence. For HBsAg-ELISA, 96 well ELISA microplates (Greiner bio-one) were coated with monoclonal mouse anti-HBsAg (Fitzgerald) and were then blocked with 2% BSA and 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS. After blocking, supernatant from infected cells was added (1:10 dilution in PBS). Plates were incubated with biotinylated monoclonal mouse anti-HBsAg (Fitzgerald). The biotinylation was performed using EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (ThermoFisher) as suggested by the provider. Pierce high sensitivity Streptavidin-HRP (ThermoFisher) was added for 30 min at 37 °C. The plates were washed three times with wash buffer (0.05% Tween-20 in PBS) after incubation with supernatant samples, biotinylated antibodies and Streptavidin-HRP. For HBeAg-ELISA, 96 well ELISA microplates were coated with monoclonal mouse anti-HBeAg (Fitzgerald) and blocked in PBS with 2% BSA and 0.05% Tween-20. After blocking, supernatant samples were addedMouse monoclonal anti-HBeAg-HRP (Fitzgerald) was added. The plates were washed three times with wash buffer after incubation with supernatant samples and HRP-conjugated antibodies. A dilution series of supernatant from HepAD38 cells was used as standard curve. The reaction was visualized by addition of TMB substrate (eBioscience) and stopped with 1 M H3PO4. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a PerkinElmer EnVision multilabel reader. For immunofluorescence HDV- and HBV-infected HepaRG cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS 5 or 10 days post infection, respectively. Cells were permeabilized with 0.25% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in PBS. VUDA serum anti-HDAg or rabbit-anti-HBcAg (DAKO) were used as primary antibodies. For quantification of infection, 4 images per treatment were acquired with an epifluorescence microscope and HDAg- or HBcAg-positive cells were quantified with ilastik software49.

Statistics

Screen data were analysed by R software21 for statistical computing. Variance was adjusted by plate and data were normalized to positive and negative controls, resulting in a B-score for each sample. Follow-up data are provided as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Graphpad Prism 5 was used for statistical analysis. Significance levels were calculated using the Student’s t-test and results were considered significant at p < 0.05. IC50 values were calculated with non-linear regression curves.

References

Dawson, P. A., Lan, T. & Rao, A. Bile acid transporters. J Lipid Res 50, 2340–2357, https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R900012-JLR200 (2009).

Yan, H. et al. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and Dvirus. Elife 1, e00049, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.00049 (2012).

Ni, Y. et al. Hepatitis B and D viruses exploit sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide for species-specific entry into hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 146, 1070–1083, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.024 (2014).

Seeger, C. & Mason, W. S. Hepatitis B virus biology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 64, 51–68 (2000).

Alvarado-Mora, M. V., Locarnini, S., Rizzetto, M. & Pinho, J. R. An update on HDV: virology, pathogenesis and treatment. Antivir Ther 18, 541–548, https://doi.org/10.3851/IMP2598 (2013).

Taylor, J. M. Virology of hepatitis D virus. Semin Liver Dis 32, 195–200, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1323623 (2012).

Lempp, F. A., Ni, Y. & Urban, S. Hepatitis delta virus: insights into a peculiar pathogen and novel treatment options. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 13, 580–589, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2016.126 (2016).

Verrier, E. R. et al. Solute Carrier NTCP Regulates Innate Antiviral Immune Responses Targeting Hepatitis C Virus Infection of Hepatocytes. Cell Rep 17, 1357–1368, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.084 (2016).

Meier, A., Mehrle, S., Weiss, T. S., Mier, W. & Urban, S. Myristoylated PreS1-domain of the hepatitis B virus L-protein mediates specific binding to differentiated hepatocytes. Hepatology 58, 31–42, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26181 (2013).

Schieck, A. et al. Hepatitis B virus hepatotropism is mediated by specific receptor recognition in the liver and not restricted to susceptible hosts. Hepatology 58, 43–53, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26211 (2013).

Gripon, P. et al. Infection of a human hepatoma cell line by hepatitis B virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99, 15655–15660, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.232137699 (2002).

Schulze, A., Schieck, A., Ni, Y., Mier, W. & Urban, S. Fine mapping of pre-S sequence requirements for hepatitis B virus large envelope protein-mediated receptor interaction. J Virol 84, 1989–2000, https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01902-09 (2010).

Bogomolov, P. et al. Treatment of chronic hepatitis D with the entry inhibitor myrcludex B: First results of a phase Ib/IIa study. J Hepatol 65, 490–498, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.016 (2016).

Li, W. & Urban, S. Entry of hepatitis B and hepatitis D virus into hepatocytes: Basic insights and clinical implications. J Hepatol 64, S32–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.011 (2016).

Lutgehetmann, M. et al. Humanized chimeric uPA mouse model for the study of hepatitis B and D virus interactions and preclinical drug evaluation. Hepatology 55, 685–694, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24758 (2012).

Blank, A. et al. First-in-human application of the novel hepatitis B and hepatitis D virus entry inhibitor myrcludex B. J Hepatol 65, 483–489, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.013 (2016).

Oehler, N. et al. Binding of hepatitis B virus to its cellular receptor alters the expression profile of genes of bile acid metabolism. Hepatology 60, 1483–1493, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27159 (2014).

Bijsmans, I. T., Bouwmeester, R. A., Geyer, J., Faber, K. N. & van de Graaf, S. F. Homo- and hetero-dimeric architecture of the human liver Na+-dependent taurocholate co-transporting protein. Biochem J 441, 1007–1015, https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20111234 (2012).

van der Velden, L. M. et al. Monitoring bile acid transport in single living cells using a genetically encoded Forster resonance energy transfer sensor. Hepatology 57, 740–752, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26012 (2013).

Zhang, J. H., Chung, T. D. & Oldenburg, K. R. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen 4, 67–73 (1999).

Brideau, C., Gunter, B., Pikounis, B. & Liaw, A. Improved statistical methods for hit selection in high-throughput screening. J Biomol Screen 8, 634–647, https://doi.org/10.1177/1087057103258285 (2003).

Azer, S. A. & Stacey, N. H. Differential effects of cyclosporin A on the transport of bile acids by human hepatocytes. Biochem Pharmacol 46, 813–819 (1993).

Dong, Z., Ekins, S. & Polli, J. E. Structure-activity relationship for FDA approved drugs as inhibitors of the human sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP). Mol Pharm 10, 1008–1019, https://doi.org/10.1021/mp300453k (2013).

Nkongolo, S. et al. Cyclosporin A inhibits hepatitis B and hepatitis D virus entry by cyclophilin-independent interference with the NTCP receptor. J Hepatol 60, 723–731, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.022 (2014).

Wang, X. J. et al. Irbesartan, an FDA approved drug for hypertension and diabetic nephropathy, is a potent inhibitor for hepatitis B virus entry by disturbing Na+-dependent taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide activity. Antiviral Res 120, 140–146, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.06.007 (2015).

Dong, Z., Ekins, S. & Polli, J. E. Quantitative NTCP pharmacophore and lack of association between DILI and NTCP Inhibition. Eur J Pharm Sci 66, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2014.09.005 (2015).

Kaneko, M. et al. A Novel Tricyclic Polyketide, Vanitaracin A, Specifically Inhibits the Entry of Hepatitis B and D Viruses by Targeting Sodium Taurocholate Cotransporting Polypeptide. J Virol 89, 11945–11953, https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01855-15 (2015).

Craddock, A. L. et al. Expression and transport properties of the human ileal and renal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter. Am J Physiol 274, G157–169 (1998).

Tsukuda, S. et al. A new class of hepatitis B and D virus entry inhibitors, proanthocyanidin and its analogs, that directly act on the viral large surface proteins. Hepatology, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28952 (2016).

Shimura, S. et al. Cyclosporin derivatives inhibit hepatitis B virus entry without interfering the NTCP transporter. J Hepatol, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.11.009 (2016).

De Bruyn, T. et al. Structure-based identification of OATP1B1/3 inhibitors. Mol Pharmacol 83, 1257–1267, https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.112.084152 (2013).

Dong, Z., Ekins, S. & Polli, J. E. A substrate pharmacophore for the human sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide. Int J Pharm 478, 88–95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.11.022 (2015).

Greupink, R. et al. In silico identification of potential cholestasis-inducing agents via modeling of Na+-dependent taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide substrate specificity. Toxicol Sci 129, 35–48, https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfs188 (2012).

Kramer, W. et al. Substrate specificity of the ileal and the hepatic Na+/bile acid cotransporters of the rabbit. I. Transport studies with membrane vesicles and cell lines expressing the cloned transporters. J Lipid Res 40, 1604–1617 (1999).

He, Z. et al. Chicago sky blue 6B, a vesicular glutamate transporters inhibitor, attenuates methamphetamine-induced hyperactivity and behavioral sensitization in mice. Behav Brain Res 239, 172–176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2012.11.003 (2013).

Leslie, E. M., Watkins, P. B., Kim, R. B. & Brouwer, K. L. Differential inhibition of rat and human Na+-dependent taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP/SLC10A1)by bosentan: a mechanism for species differences in hepatotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 321, 1170–1178, https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.106.119073 (2007).

Ho, R. H. et al. Drug and bile acid transporters in rosuvastatin hepatic uptake: function, expression, and pharmacogenetics. Gastroenterology 130, 1793–1806, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.034 (2006).

Lindor, K. D. et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 50, 291–308, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22906 (2009).

Dilger, K. et al. Effect of ursodeoxycholic acid on bile acid profiles and intestinal detoxification machinery in primary biliary cirrhosis and health. J Hepatol 57, 133–140, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.014 (2012).

AstraZenecaPharmaceuticals. Accolate (zafirlukast) tablet, https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/archives/fdaDrugInfo.cfm?archiveid=2948 (2006).

FDA. Avandia (rosiglitazone maleate) tablets, https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm143413.pdf (2007).

FDA. Azulfidine sulfasalazine tablets, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/007073s124lbl.pdf (2009).

T3TB. Tiratricol (T3D4983), http://www.t3db.ca/toxins/T3D4983 (2014).

Wishart. Drugbank, https://www.drugbank.ca/ (Version 5.0).

Rust, C. et al. Sulfasalazine reduces bile acid induced apoptosis in human hepatoma cells and perfused rat livers. Gut 55, 719–727, https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2005.077461 (2006).

Walters, H. C., Craddock, A. L., Fusegawa, H., Willingham, M. C. & Dawson, P. A. Expression, transport properties, and chromosomal location of organic anion transporter subtype 3. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 279, G1188–1200 (2000).

Ladner, S. K. et al. Inducible expression of human hepatitis B virus (HBV) in stably transfected hepatoblastoma cells: a novel system for screening potential inhibitors of HBV replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41, 1715–1720 (1997).

Kuo, M. Y., Chao, M. & Taylor, J. Initiation of replication of the human hepatitis delta virus genome from cloned DNA: role of delta antigen. J Virol 63, 1945–1950 (1989).

Sureau, C., Fournier-Wirth, C. & Maurel, P. Role of N glycosylation of hepatitis B virus envelope proteins in morphogenesis and infectivity of hepatitis delta virus. J Virol 77, 5519–5523 (2003).

Sommer, C. S. C., Köthe, U. & Hamprecht, F. A. 230–233 (Eighth IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) Proceedings, 2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Fabian Saveedra for helping with the many taurocholate uptake experiments and cell viability tests, Karin Prummel for generating the pcDNA3-mNTCP expression plasmid, and Paul Dawson for providing the MDCK cells stably expressing ASBT. We also thank Yi Ni and Thomas Tu for their technical support with the ELISA experiments and HBV DNA quantification, both of them together with Florian A. Lempp for virus production, and Franziska Schlund for HepaRG cell culture. SvdG is supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (Vidi; 91713319) and the European Research Council (Starting grant 337479). BZ and SU received funding from the SFB 1129 and the German Center for infectious diseases (DZIF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D. carried out experiments. B.Z. performed the HBV/HDV infection studies under supervision of S.U. The cheminformatics modeling was performed by G.v.W. under supervision of A.I.J. M.K. operated the Operetta and converted the data to be used for analysis. Study concept and design: J.D., R.O.E., S.U., S.v.d.G. Drafting and initial review of the manuscript: J.D., G.v.W., A.I.J., B.Z., S.U., R.O.E., S.v.d.G. S.v.d.G. and S.U. obtained funding. All authors were involved in analysis and interpretation of data and have read the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

Stephan Urban is co-applicant and co-inventor on patents protecting HBV preSderived lipopeptides (Myrcludex B) for the use of HBV/HDV entry inhibitors. The other authors who have taken part in this study declared that they do not have anything to disclose regarding funding or conflict of interest with respect to this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Donkers, J.M., Zehnder, B., van Westen, G.J.P. et al. Reduced hepatitis B and D viral entry using clinically applied drugs as novel inhibitors of the bile acid transporter NTCP. Sci Rep 7, 15307 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15338-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15338-0

This article is cited by

-

Bulevirtide als erster spezifischer Wirkstoff gegen Hepatitis-D-Virusinfektionen – Mechanismus und klinische Wirkung

Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz (2022)

-

Selective hepatitis B and D virus entry inhibitors from the group of pentacyclic lupane-type betulin-derived triterpenoids

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Role of Nucleic Acid Polymers and Entry Inhibitors in Functional Cure Strategies for HBV

Current Hepatology Reports (2020)

-

Role of Sodium Taurocholate Cotransporting Polypeptide as a New Reporter and Drug-Screening Platform: Implications for Preventing Hepatitis B Virus Infections

Molecular Imaging and Biology (2020)

-

Generation and characterization of a stable cell line persistently replicating and secreting the human hepatitis delta virus

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.