Abstract

Manipulation of a single abiotic stress-related gene could improve plant performance under abiotic stress conditions. To simultaneously increase plant tolerance to multiple stresses, it is usually required to overexpress two (or more) genes in transgenic plants. The common strategy is to assemble two or more expression cassettes, where each gene has its own promoter and terminator, within the same T-DNA. Does the arrangement of the two expression cassettes affect expression of the two transgenes? Can we use the Drosophila gypsy insulator sequence to increase the expression of the two transgenes? Answers to these questions would contribute to design better transformation vectors to maximize the effects of multi-gene transformation. Two Arabidopsis genes, PP2A-C5 and AVP1, and the gypsy insulator sequence were used to construct six transformation vectors with or without the gypsy insulator bracketing the two expression cassettes: uni-directional transcription, divergent transcription, and convergent transcription. Total RNAs were isolated for reverse transcription- quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) assays and a thorough statistical analysis was conducted for the RT-qPCR data. The results showed that the gypsy insulator does promote the expression of two transgenes in transgenic plants. Besides, the plants containing the divergent transcription cassettes tend to have more correlated expression of both genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since 1983, transgenic technology has been a popular method for modifying target plants to enhance their adaptation to various environmental challenges1. For examples, overexpression of the Arabidopsis vacuolar membrane Na+/H+ reverse transport protein 1 gene (AtNHX1) that encodes the vacuolar membrane bound protein/sodium antiporter leads to increased salt tolerance2, whereas overexpression of the transcriptional factor C-repeat/DRE Binding Factor 1 gene (CBF1) leads to enhanced cold tolerance3,4. In general, overexpressing genes encoding functional proteins, such as enzymes or channel proteins, lead to specific but limited changes in transgenic plants; overexpressing genes encoding regulatory proteins such as transcriptional factors tend to cause side effects in transgenic plants including negative impacts on plant growth and development5,6. Consequently, in order to obtain better results in transgenic plants, we must optimize transgene expression either by co-overexpressing multiple functional protein genes or fine-tuning the expression of regulatory genes. Thus, it is vital to develop multiple gene transformation technologies which could transfer two or more genes into plants to obtain remarkable changes in plant phenotype or to establish a new metabolic pathway in plants7. Studying the interaction between two co-expressing genes was the first step toward a multiple gene transformation system. Multiple genes could be stacked in transgenic plants by transforming linked genes (multiple genes on the same plasmid), crossing different transgenic plants, or performing sequential or co-transformations8. Among these multiple gene transformation technologies, the transformation of linked genes has been regarded as the most convenient and reliable method so far9.

Drought and high salinity are two major abiotic stresses threatening agricultural productivity and food security. At present, over 20% of irrigated lands are affected by drought and salt stresses in many countries10, and the situation is continually deteriorating. The Arabidopsis vacuolar H+-pyrophosphatase 1 (AVP1) is encoded by a 3,530-bp single copy gene with seven introns. The product of AVP1 is a proton pump located on vacuolar membranes, and overexpression of AVP1 increases drought and salt resistance in transgenic Arabidopsis11. Overexpression of AVP1 establishes a higher H+ gradient that energizes a secondary transporter, such as Na+/H+ antiporter, to uptake more K+, reducing the toxicity of Na+, which leads to enhanced salt resistance in plants12. AVP1 has been introduced into tomato13, tobacco14 and cotton15 to improve drought or salt resistance in these species. Moreover, the polar transport of auxin, which regulates the development of roots and sprouts, is also stimulated by overexpression of AVP1 16. Co-overexpression of AVP1 and AtNHX1 by crossing AVP1-overexpressing cotton with AtNHX1-overexpressing cotton has been achieved to further improve salt resistance in cotton17.

Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is a subgroup of the very complex serine/threonine protein phosphatase family and consists of a scaffolding subunit, a regulatory subunit, and a catalytic subunit. PP2A-C5 is one of the five genes encoding the catalytic subunit of PP2A in Arabidopsis, and it plays an important role in plant salt resistance. Overexpression of PP2A-C5 leads to increased salt tolerance in transgenic plants and the loss of function mutant of this gene, pp2a-c5-1, is sensitive to salt treatment18. A hypothesis about how PP2A-C5 participates in plant response to salt stress suggests that PP2A might activate the chloride channel (CLC) proteins CLCa and CLCc on vacuolar membrane by removing the phosphate group from CLCa and CLCc18. Both CLCa and CLCc use proton as the driving force to move chloride and nitrate ion into vacuole19, and the proton gradient is generated by AVP1 and ATPase on the vacuolar membrane. We thought that perhaps it was possible to further increase salt tolerance by co-overexpressing AVP1 and PP2A-C5, as overexpression of AVP1 provides more protons inside vacuoles that can be used by CLCa and CLCc to exchange for chloride and nitrate, and overexpression of PP2A-C5 activates CLCa and CLCc. To achieve this goal, we need to construct a vector that would allow us to efficiently express both AVP1 and PP2A-C5.

The construction of the transformation vector is the first step in generating transgenic plants and this step plays an important role in transgene expression efficiency. When two or more open reading frames (ORFs) are integrated on one plasmid as linked genes, each exogenous gene is transcribed independently because every ORF has its own promoter, enhancer, and terminator. However, this method has a disadvantage that it is very difficult to control the transcript levels of multiple transgenes, because stacking of multiple strong promoters might cause silencing. Therefore, it will cost extra time and labor to obtain transgenic lines with the desirable level of transgene transcripts19,20. In addition, the transgene’s promoters might compete for RNA polymerase II, resulting in unexpected differential expression levels of two genes21. This could be the reason why some plants co-overexpressing multiple anti-stress genes don’t perform better than a single gene transgenic plants22,23. Besides, in some cases, variation of gene expression might even lead to totally unexpected plant phenotypes24.

The gypsy element, a DNA insulator, was originally found in Drosophila and is 395-bp long25. It blocks influences from nearby enhancers or prevents the heterochromatinization of chromosomes26,27. It may increase the expression of reporter genes when it is inserted at the two flanks of the reporter gene28. However, very few studies have been reported on the use of gypsy to improve transgene expression in plants. In this study, we constructed three two-gene expression vectors that had uni-directional (→→), divergent (←→), and convergent (→←) arrangements for transcription direction of transgenes PP2A-C5 and AVP1, as well as three vectors that had the same arrangements for PP2A-C5 and AVP1 with additional gypsy elements on both sides of the two transgene cassettes. The transcript levels of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 were analyzed to investigate the role of vector’s structure and gypsy insulator in the transcription of both genes. Our results can be used to guide vector design for less labor intensive and more efficient multiple transgene expression.

Results

Construction of six two-gene co-transformation vectors and Arabidopsis transformation

To study the impact of expression cassettes arrangement and the gypsy insulator in the T-DNA on transgene transcription in transgenic plants, we constructed six two-gene co-overexpressing vectors for Arabidopsis transformation (Fig. 1). The two genes used are 35S promoter driven PP2A-C5 and dual-35S promoter driven AVP1 (see Materials and Methods). The neomycin resistance gene NPTII was used as the selective marker in plant transformation (Fig. 1). The two expression cassettes without or with the gypsy insulator bracketing transgene cassettes are arranged in the following three ways: 1) uni-directional transcription of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 (→→, vectors A and D), divergent transcription (←→, vectors B and E), and convergent transcription (→←, vectors D and F). No gypsy insulators are in the vectors A, B and C, whereas the gypsy insulator flanks the two expression cassettes in vectors D, E and F (Fig. 1). The directions of transgene cassettes and the presence of gypsy insulators were verified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and agarose gel electrophoresis (Supplementary Figs S1 and S2)

Schematic overview of six two-gene co-transformation vectors. The positions and relative orientations of PP2A-C5 with its promoter and terminator sequences (p35S-PP2A-C5), AVP1 with its promoter and terminator sequences (pdual35S-AVP1), and a selective marker gene with its promoter and terminator sequences (p35S-NPTII) are shown with respect to the right border (RB) and the left border (LB) of the T-DNA regions. A and D, uni-directional transcription vectors for PP2A-C5 and AVP1 expression cassettes (→→); B and E, divergent transcription vectors for PP2A-C5 and AVP1 expression cassettes (←→); C and F, convergent transcription vectors for PP2A-C5 and AVP1 expression cassettes (→←). Gypsy elements (G) bracket the PP2A-C5 and AVP1 expression cassettes in vectors D, E, and F.

These six transforming vectors were introduced into wild-type Arabidopsis plants (ecotype Columbia, Col) using the ‘floral dip’ method of Clough and Bent29. In total, 292, 828, 289, 243, 309, and 219 independent T1 transgenic plants containing vectors A, B, C, D, E and F, respectively, were obtained. Then, 45 seeds of each independent transgenic line were screened on Murashige and Skoog (MS) plates supplemented with kanamycin (30 mg L−1) for segregation analysis. Plants that showed roughly 3 to 1 segregation ratio of kanamycin resistance to sensitivity phenotype were identified as potential single T-DNA insertion plants. 100, 70, 98, 92, 99 and 88 independent putative single T-DNA insertion transgenic lines containing vectors A, B, C, D, E and F, respectively, were obtained. These 547 transgenic plants were used for further analyses.

Validating RT-qPCR results by RNA blot

To analyze gene expression, two methods are commonly used to analyze gene transcript level: RNA blot analysis and reverse transcription-quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis. RNA blot results are semi-quantitative and highly reliable, while RT-qPCR results are more quantitative. The RT-qPCR was used to analyze the transcript levels of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 in the six transgenic populations. To make sure that the RT-qPCR results are accurate and trustable, we randomly selected 9 independent transgenic lines from the transgenic plants containing vector A and analyzed the PP2A-C5 and AVP1 transcript levels with both RNA blot and RT-qPCR methods. The RNA blot results showed that transgenic lines A4, A17 and A19 contained high AVP1 transcript level as well as significantly increasing PP2A-C5 transcript level in A19. And the transcript levels of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 were both relatively low in lines A3 and A22 (Fig. 2a). Similar results were obtained by RT-qPCR method (Fig. 2b). This suggested that RT-qPCR could serve as a reliable tool in analyzing transcript levels of both transgenes in transgenic plants.

Correlation of RNA blot data and quantitative PCR data. (a) RNA blot analysis of nine independent AVP1/PP2A-C5 co-expressing plants. WT, wild-type plant; A3 to A22, nine randomly selected independent AVP1/PP2A-C5 co-expressing plants. The probes used are indicated on the left. The gene Actin2 was used as RNA loading control. The blots are cropped and the full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S4. (b) Quantitative PCR analysis of the nine randomly selected AVP1/PP2A-C5 co-expressing plants. Each dot represents an independent transgenic line. The transcript levels of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 relative to the level of Actin2 in wild-type plant were set as 1. The fold of change for AVP1 or PP2A-C5 transcript was used to reflect the overexpression levels of transgenes in transgenic plants. The y-axis represents the fold of change for PP2A-C5 transcript. The x-axis represents the fold of change for AVP1 transcript. Each data point is the mean value of three repeats in RT-qPCR. Error bars represent standard deviations.

All vectors can overexpress AVP1 and PP2A-C5

The total RNAs from all single T-DNA insertion lines were extracted and used for reverse transcription, followed by RT-qPCR analysis. The transcript levels of AVP1 and PP2A-C5 in wild-type plants were set as 1 and the fold of change (FOC) in AVP1 or PP2A-C5 transcript was used to reflect the transcription levels of transgenes in transgenic plants. A value of over 1 indicates increased transcript for transgene, a value of smaller than 1 indicates decreased transcript for the transgene being analyzed. The summary of results of 1094 RT-qPCR analyses (547 for AVP1 and 547 for PP2A-C5) are shown in Table 1 and the calculated proportions of transgene overexpression lines are shown in Table 2. To better illustrate the FOC in PP2A-C5 and AVP1 transcript in these six transgenic populations, the FOC for AVP1 and PP2A-C5 in each individual plant in a particular transgenic population are shown as the Scatter diagrams in Fig. 3. It is clear that both PP2A-C5 and AVP1 are overexpressed in most of these transgenic plants (>72%, Table 2). The average FOC for PP2A-C5 ranged from 2.829 to 5.977, while the average FOC for AVP1 ranged from 2.233 to 3.783 (Table 1). Evidently, all six co-transforming vectors can be used for co-overexpressing both transgenes in Arabidopsis. Furthermore, our results also indicate that transgenic plants independently containing uni-directional or convergent transcription cassettes (vectors A, C, D and F) have higher FOC in PP2A-C5 transcript compared with that of AVP1 and transgenic plants independently containing divergent transcription cassettes (vectors B and E) have a more similar, or ‘balanced’ (points distributed more evenly on both sides of line y = x in Fig. 3) FOC for AVP1 and PP2A-C5 transcripts (Fig. 3). This interesting difference is discussed more in later sections.

The distribution of transcript levels of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 in six transgenic populations. (a), (b), (c), (d), (e) and (f) Quantitative PCR data of transgenic plants containing the corresponding vector. Each dot represents a single T-DNA insertion line. The transcript levels of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 relative to that of Actin2 in wild-type plant were set as 1. The fold of change for AVP1 or PP2A-C5 transcript was used to reflect the increased transcript levels of transgenes in the transgenic plants. The y-axis represents the fold of change for PP2A-C5 transcript. The x-axis represents the fold of change for AVP1 transcript. The dots near the diagonal (solid lines) represent the transgenic lines which have a ‘balanced’ PP2A-C5 and AVP1 overexpression level. Each data point is the mean value of three repeats of RT-qPCR analyses. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Transgenic plants containing vectors that include the gypsy insulators display higher FOCs for both transgene transcripts

To test whether the gypsy insulator could enhance the transcription of AVP1 and PP2A-C5, the FOCs for AVP1 and PP2A-C5 transcripts from plants transformed with vectors D, E and F were compared with those from plants transformed with vectors A, B and C (Table 1). The gypsy insulators in vectors D, E and F helped transgenic plants maintain higher average FOC for AVP1 and PP2A-C5 transcripts (Table 1 and Fig. 3), and the variances of FOC for AVP1 and PP2A-C5 transcripts in transgenic plants containing the gypsy insulators were increased (Table 1). In addition, the gypsy insulators could increase the maximal value of FOC for AVP1 transcript in populations transformed with vectors D, E or F as well as the maximal value of FOC for PP2A-C5 in populations transformed with vectors D or F. In population transformed with the vector E, the maximal value of FOC for AVP1 was the highest among all six transgenic populations, but the maximal value of FOC for PP2A-C5 was lower than that of the transgenic plants transformed with vector B by contraries (Table 1). Moreover, the proportion of plants displaying higher than 2 FOC for both AVP1 and PP2A-C5 transcript increased in all three populations containing gypsy insulators (Table 2).

To further evaluate gypsy’s effects on gene expression, the FOC for AVP1 and PP2A-C5 transcripts in six groups of transgenic plants were analyzed using the software of IBM SPSS Statistics 22. The single-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test showed that the distributions of FOC for AVP1 and PP2A-C5 transcripts were not within the Normal distribution (p < 0.05). Thus, the median method and Wilcoxon rank test were applied to compare these six groups of transgenic plants (Fig. 4). The results indicated that the FOC for PP2A-C5 transcript was significantly increased by 49.67%, 58.79% and 84.50% in plants independently containing vectors D, E or F, as compared with plants independently containing vectors A, B or C, respectively (Fig. 4a). Similarly, the FOC for AVP1 transcript was increased by 11.96%, 9.67% and 13.10% in plants independently containing vectors D, E or F, as compared with plants independently containing vectors A, B or C, respectively (Fig. 4b). However, the increase of FOC for AVP1 transcript was significant in plants independently containing vectors D or F, but not in plants containing vector E. Thus, the gypsy insulator can significantly increase PP2A-C5 transcript in all three expression cassette arrangements, but can only significantly increase AVP1 transcript in uni-directional and convergent arrangements of expression cassettes.

Comparison of the medians of increased transcript levels of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 in six groups of transgenic plants. (a) The medians of PP2A-C5 transcript levels obtained from quantitative PCR analyses in six transgenic populations. (b) The medians of AVP1 transcript levels obtained from quantitative PCR analyses in six transgenic populations. Because the distribution of fold of change for PP2A-C5 or AVP1 transcript was not within the Normal distribution (p < 0.05), the median method and Wilcoxon rank test were applied to compare these six groups of transgenic plants. The transcript levels of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 relative to that of Actin2 in wild-type plant were set as 1. The fold of change for AVP1 or PP2A-C5 transcript was used to reflect the increased transcript levels of transgene transcripts in transgenic plants. The x-axis represents the fold of change for PP2A-C5 transcript (a) or AVP1 transcript (b). The transgenic plants containing corresponding vector were labeled on the left. An asterisk indicates a significant difference in comparisons between plants populations containing vectors A and D, B and E, and C and F, respectively. Statistical significance was determined by a Wilcoxon rank test at p < 0.05.

Expression of AVP1 and PP2A-C5 is biased but correlated

As mentioned before, the FOC for PP2A-C5 transcript is higher than FOC for AVP1 transcript in four out of the six transgenic populations (Fig. 3), which might indicate different preference to express the two genes of vectors with different arrangement. The FOC for each gene’s transcript was further examined (Fig. 5). Indeed, the FOC for AVP1 transcript was higher than that of PP2A-C5 transcript in over 50% of the transgenic plants transformed either with vector B or vector E, while much smaller portion of plants showed higher FOC for AVP1 transcript than that for PP2A-C5 in plants transformed with vectors A, C, D or F (31%, 23.5%, 25.0%, and 6.8%, respectively, Fig. 5). Moreover, the divergent expression cassettes arrangement of transgenes (vectors B or E) displayed higher maximal FOC for AVP1 transcript and lower maximal FOC for PP2A-C5 transcript (Table 1). Considering that AVP1 is expressed at a much higher level than that of PP2A-C5 endogenously in Arabidopsis, this indicates a stronger bias towards expressing AVP1 over PP2A-C5 in plants containing the divergent expression vectors.

Comparisons between PP2A-C5 and AVP1 transcript in six transgenic populations. The transcript levels of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 relative to that of Actin2 in wild-type plants were set as 1. The fold of change for AVP1 or PP2A-C5 transcript was used to reflect the increased transcript levels of transgenes in the transgenic plants. Data from RT-qPCR analyses were used for further calculation. Black column represents the proportion of plants in which the fold of change for PP2A-C5 transcript was higher than that for AVP1 transcript, and the grey column indicates the opposite situation. The transgenic populations containing corresponding vectors were labeled on the bottom.

To further study the expression pattern of these two transgenes in these transgenic plants, we analyzed the correlation of AVP1 transcript’s FOC and PP2A-C5 transcript’s FOC. There is a significant positive correlation between the up-regulated AVP1 transcript level and PP2A-C5 transcript level in all of these plants (Fig. 6). The highest correlation was found in plants containing vector B (0.76) and the lowest correlation was observed in plants containing vector D (0.45) (Fig. 6). Interestingly, plants containing constructs with the gypsy elements bracketing the two gene expressing cassettes showed lower correlations in comparison with plants containing constructs without gypsy elements in two out three arrangements (unidirectional and divergent) (Fig. 6). We used Fisher’s Z test to compare the correlation values among these six transgenic populations as well and found that the correlation in transgene transcriptions in plants containing vector D was significantly lower than those in plants containing vectors A, B, E or F. Moreover, the FOC for AVP1 and PP2A-C5 transcript appeared to be more closely related (higher correlation) when the two transgenes transcribed divergently (vectors B and E), with or without the gypsy element (Fig. 6).

The correlation between PP2A-C5 transcript level and AVP1 transcript level. The transcript levels of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 relative to that of Actin2 in wild-type plants were set as 1. The fold of change for AVP1 or PP2A-C5 transcript was used to reflect the increased transcript levels of transgenes in the transgenic plants. Data from RT-qPCR analyses were used for further calculation. The correlation value between of PP2A-C5 transcript and AVP1 transcript was calculated using IBM SPSS Statistics 22. The y-axis represents the correlation between the fold of change for PP2A-C5 transcript and AVP1 transcript. Values above zero represent the increased transcript levels of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 are positively correlated and the closer the value is to 1, the stronger the correlation between overexpression of the two transgenes is. To compare the correlation coefficients, Fisher’s Z is used to constructs the 95% confidence intervals for all groups. Error bars indicate lower and upper values of confidence intervals. A non-overlapping of confidence intervals between two data groups indicates a significant difference. The transgenic plants populations containing corresponding vector were labeled on the bottom.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that co-transformation of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 expression cassettes arranged in three different ways, either with or without the gypsy insulator, can increase the transcript levels of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 in Arabidopsis transgenic plants. In plants populations with single T-DNA insertion, 33% to 48% of total showed higher than 2 FOC for both genes’ transcripts compared with wild-type plants (Table 2). This proved the concept that expression of linked genes is an effective way to obtain transgenic plants overexpressing two genes, consistent with the conclusion of previous investigation8. Previous study reported that while introducing exogenous genes into plants, there are three major factors that could affect the expression of transgenes: copy number of transgene, location of integration, and complex mechanisms of regulation30,31,32. In our study, in order to remove influences of multiple copies of transgenes and the positional effects of T-DNA insertions, 100, 70, 98, 92, 99, and 88 independent single T-DNA insertion lines were analyzed. Although the latter two factors could not be controlled easily, it is practicable to alleviate their impact by increasing the number of independent transgenic lines for each transformation vectors. Analysis of relatively large population can statistically eliminate the influence of rare events caused by unknown mechanisms. Additionally, because we used the FOC for AVP1 and PP2A-C5 transcript in transgenic plants compared with wild-type, which is a relative quantitative method, to reflect the transcription levels of transgenes, it also remove the background deviation caused by transgenic technology itself. Also, to increase the accuracy of our detection, RT-qPCR was used to evaluate the FOC for gene’s transcript and confirmed with RNA blot. Thus, we believed that our study could correctly reveal the influence of transgene expression cassettes arrangement and the gypsy insulator on the transcription of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 in transgenic Arabidopsis.

The main purpose of our study was to investigate the effects of different expression cassette arrangements on transgene expression. Plant characteristics can be dramatically changed by simply increasing the expression of a particular transcription factor gene33. However, overexpressing an exogenous transcription factor gene could result in negative effects on plant growth6 and different expression patterns of transgenes in multi-gene expression cassettes may also lead to totally opposite phenotypes34,35. Moreover, co-overexpression of two or more genes is an energy consuming process and can place a large burden on plant growth and development. For example, when a whole metabolic pathway in plants needs to be modified or established, how to control the precise expression of each transgene in multi-gene expression cassettes is extremely important. Thus, the assembly of co-expressing genes and elements plays an important role in the construction of multi-gene expression cassettes. Here, we assembled PP2A-C5 and AVP1 expression cassettes in three different ways, and all three arrangements could increase the transcription of both transgenes. The results suggested that if PP2A-C5 and AVP1 expression cassettes were assembled in a divergent way, the changes of their transcription level were similar to each other and more correlated to each other (Table 1, Figs 3 and 6). We assume that when PP2A-C5 and AVP1 were transcribed divergently (Fig. 1), a bi-directional promoter structure was created36 and the RNA polymerase II could bind to the promoter of both expression cassettes in a coordinated fashion. On the contrary, in plants independently containing vectors A, C, D or F, in which the PP2A-C5 and AVP1 expression cassettes were either assembled in uni-directional or convergent way, the transcription of PP2A-C5 was enhanced and correlation between FOC of AVP1 and PP2A-C5 was decreased compared with those in plants containing vectors B or E (Table 1, Figs. 3 and 6). This might be due to several factors. Firstly, distance between the two promoters might lead to more independent transcription initiation and less correlation between their transcriptions. Secondly, readthrough of RNA polymerase II might affect transcription of downstream genes, such as AVP1 and PP2A-C5 expression cassettes in unidirectional or convergent arrangements. This could be due to antisense-RNA or even simply steric hindrance suppressing RNA Polymerase II assembly. In our case, PP2A-C5 is much shorter than AVP1, which might cause more readthrough and stronger negative effect on AVP1. The similar transcriptional suppression of convergently or uni-directionally transcribed genes was also noticed by Chen et al.37. Thus, we conclude that expressing two genes in divergent way can achieve a more correlated transcription of both transgenes, while expressing two genes in uni-directional or convergent way could incur more competitive and less correlated transcriptions of transgenes.

The other purpose of our study was to investigate the function of the gypsy insulator in the expression of two transgenes. There are applications of gypsy as a cis-element in several species38,39,40. In Arabidopsis, gypsy increased the expression of a reporter gene28. Gypsy not only enhanced the expression of genes located between the two gypsy sequences, but also enhanced the expression of genes near the gypsy element28. Blocking enhancers nearby or preventing DNA from heterochromatinization may be the two major functions of gypsy 26,27, and the functions are distance related and orientation independent26. In our study, we extended the investigation of gypsy to abiotic stress-related genes. With the addition of the gypsy insulator, the PP2A-C5 and AVP1 transcript levels tend to increase, with the former more than the latter (Table 1, Fig. 4), and the proportion of plants showing FOC for both genes’ transcripts higher than 2 folds of wild-type levels increases, too (Table 2). In the plants containing vectors D, E or F, the FOC for PP2A-C5’s transcript was significantly increased by 49.67%, 58.79% and 84.50%, respectively (Fig. 4a) in comparison with plants containing the similar vectors except without gypsy. Although the increase in AVP1 transcription (9.67%) in plants containing vector E, compared with plants containing vector B, was not significant, the increase in plants containing vectors D or F (11.96% and 13.10%, respectively) (Fig. 4b), compared with plants containing vectors A or C, was significant. This may be due to the increase of AVP1 transcript level in plants containing vector E was too small to be detected. Besides, in wild-type plants, the endogenous transcript of AVP1 was 22 to 23 times higher than the transcript of PP2A-C5. This might lead to significantly higher increase in PP2A-C5 transcript in the presence of gypsy. In addition, gypsy could also increase the variance of FOC for PP2A-C5 and AVP1 transcript and the maximal FOC values for AVP1 transcript in transgenic populations containing vectors D, E, or F. Meanwhile, it could increase the maximal FOC values for PP2A-C5 transcript in transgenic plants containing vectors D or F (Table 1). Besides, with the addition of gypsy, the correlation between FOC for PP2A-C5 and AVP1 transcripts was significantly decreased in transgenic population containing uni-directional construct (Fig. 6). The gypsy’s influence on correlation values in populations independently containing vectors D, E or F, compared with plants independently containing vectors A, B or C, was not significant. We assume that the gypsy may stabilize transcription by reducing the interference between two co-expressing genes, and the relative stronger interference between two genes in uni-directionally and convergently transcribed vectors than in divergently transcribed vector may contribute to the more significant change for genes’ transcripts in vectors D and F. Thus, we conclude that in the presence of gypsy insulator, the transcript level of both transgenes can be increased in all two-gene expression cassettes arrangements at the cost of increased variation and potentially decreased correlation.

Hence, our results can assist the selection of proper vector construction when designing co-expression of multiple genes for different purposes. Without adding the gypsy insulator, uni-directionally, divergently or convergently transcribed vector can all provide highly correlated enhanced transcription of two transgenes (Table 1, Fig. 6). The uni-directionally and convergently arranged vectors can be used to specifically overexpress one major gene and co-overexpress the other by tuning the order of the two transgenes. The divergently arranged vector can overexpress two genes in a more correlated way (Figs 3 and 5), which means less number of plants to screen for transgenic lines highly overexpressing both genes. On the other hand, with the addition of the gypsy insulator, uni-directionally and convergently transcribed vectors can generate transgenic plants with higher transcript level of transgenes (Table 1). Unfortunately, this increase is accompanied by increased variance within the population and reduced correlation between the enhancements of two transgenes’ transcripts, which means in order to obtain higher transcription more independent transgenic lines are needed. If it is expected to simultaneously overexpress two transgenes as highly as possible and it is easy to obtain a large number of transgenic plants, for example, in Arabidopsis, the uni-directionally and convergently transcribed vectors containing gypsy would be the best choice. However, in some species, such as cotton, to obtain a large number of transgenic plants to screen for high overexpression plants are time- and labor-consuming. It is better to select divergently transcribed vector containing gypsy for transformation due to the higher correlation. In summary, our work provides a new perspective on multiple genes overexpression in plants. This study can serve as a guideline for vector construction in biotechnology research.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The Arabidopsis ecotype Columbia-0 (Col-0) was used in this study. Arabidopsis seeds (approximate 20 μL) were sterilized in 15% bleach (KIK international Inc., Houston, TX, USA) for 30 min, followed by washing with sterile distilled water three times to remove the bleach. Seeds were kept in at 4°C for 24 h. Then, were suspended in 3 drops of 0.07% agarose (AMRESCO) and plated on 1/2 Murashige and Skoog (MS) plates41. Plants were grown under continuous light conditions at 22°C (ambient temperature). After 12 days of culturing on plates, the plants were transferred to soil and grown in a growth chamber (ENCONAIRAC-60, Ecological Chamber Inc., Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada) with a 16 h light: 8 h dark photoperiod at a light intensity of 120 mmol s−1m−2 and 22 °C with 50% relative humidity. Distilled water was used for watering in our experiments.

Construction of basic vector containing gypsy

The binary vector pPZP212, Escherichia coli DH5α and Agrobacterium strain GV3101 from our laboratory were used in this experiment. The gypsy fragments were cloned from pGYPSY-TL-Su(Hw), which was donated by Dr. Junhui Wang28, by PCR (Q5® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase, New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA). The gypHX35 (primers: Gyp3 and Gyp-xho-hin5) and gypES35 (primers: Gyp3 and Gyp-sac-eco5) fragments were amplified. pPZP212 was digested with HindIII, treated with T4 DNA polymerase and then digested with SalI to generate a linear background vector with one blunt end and one sticky end. The linear fragment was treated with alkaline phosphatase (New England Biolabs) to prevent vector’s self-ligation. Then, the XhoI-digested gypHX35 fragment was ligated to the linear fragment to form pPZP212-5G. pPZP212-5G was digested with EcoRI, treated with T4 DNA polymerase and then digested with SacI after alcohol precipitation and purification to generate a new linear fragment with one blunt end and one sticky end. The SacI-digested gypES35 fragment was ligated to the new fragment to form the circular plasmid pPZP212G with two gypsy insulators flanking the multi-cloning site. The plasmid was then ready for the insertion of the gene expression cassette.

Construction of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 co-expression vectors with gypsy

The PP2A-C5 expression cassette originated from the pFGC5941-C5 plasmid18. The pFGC5941-C5 plasmid was partially double-digested with HindIII and EcoRI to release a 3,198-bp DNA fragment. This fragment contained the PP2A-C5, 35S promoter and the octopine synthase terminator sequence. pPZP212G was also double-digested with HindIII and EcoRI, and ligated with the 3,198-bp fragment to form the p212G-C5 vector. The AVP1 gene was amplified by PCR from an Arabidopsis cDNA library using Q5® High-Fidelity DNA polymerase with primers AVP1-F1 and AVP1-R1. The blunt-end AVP1 was then ligated to pRT103 and digested with SmaI to form pRT103-AVP, which contained a dual 35S promoter and polyadenylation signal of the CaMV strain Cabb B-D42. pRT103-AVP was sequenced (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) and then digested with HindIII to release the AVP1 expression cassette. Meanwhile, pPZP212 and p212G-C5 were treated with HindIII and dephosphorylated by alkaline phosphatase to prevent self-ligation. These two linear fragments were ligated into the AVP1 expression cassette to form pPZP212-AVP and two co-expression vectors, p212G-C5-AVPU (→→, named ‘vector D’) and p212G-C5-AVPC (→←, named ‘vector F’). The directions of the insertions were determined by PCR. p212G-C5-AVPU was treated with EcoRI to release the PP2A-C5 expression cassette and dephosphorylated by alkaline phosphatase. pFGC5941-C5 was treated with HindIII and alkaline phosphatase to prevent self-ligation. A 340-bp fragment was released by HindIII from pJG4-543 (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., CA, USA) and then ligated with linearized pFGC5941-C5 to form pFGC5941-EC5E. Then, the PP2A-C5 expression cassette released from pFGC5941-EC5E by EcoRI was ligated with linearized p212G-C5-AVPU to form p212G-C5-AVPD (←→, named ‘vector E’).

Construction of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 co-expression vectors not containing gypsy

The PP2A-C5 expression cassette released from pFGC5941-EC5E by EcoRI was ligated with linearized pPZP212-AVP after treatment with EcoRI and alkaline phosphatase to form p212-C5-AVPU (→→, named ‘vector A’) and p212-C5-AVPD (←→, named ‘vector B’). The AVP1 expression cassette released from pRT102-AVP after treatment with HindIII was ligated with p212-C5-AVPU (→→) to form p212-C5-AVPC (→←, named ‘vector C’).

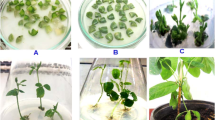

Transformation of Arabidopsis

Vectors A, B, C, D, E and F were transferred into Agrobacterium and then transformed into Arabidopsis (T0 generation) using the ‘floral dip’ method29. Seeds of the T0 generation were surface sterilized with 15% bleach and plated on 1/2 MS medium containing 50 mg L−1 cefotaxime and 50 mg L−1 kanamycin to screen for positive transgenic plants (T1 generation). The putative positive transgenic plants at the four true leaf stage were transferred into soil, and the seeds (T2 generation) were harvested. The T2 generation were cultured on 1/2 MS medium containing 30 mg L−1 kanamycin (45 seeds per transgenic line) to select single-insertion transgenic plants using Mendel 3:1 segregation analysis. The DNA of T2 seedling were extracted44 and subjected to PCR with GoTaq DNA Polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) to identify the insertion of gypsy, PP2A-C5 and AVP1.

Analyses of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 relative expression levels

Seeds of the putative single insertion T1 generation were grown on 1/2 MS medium for nine days. RNA was extracted from over 50 seedlings of each line using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). The purity and concentration of RNA were determined (NanoDrop ND-1000, Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). Then 1 μg of total RNA was used for reverse transcription to make cDNA with an iScript cDNA synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Relative quantification (RT-qPCR) analyses were carried out using SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad) on an ABI7500 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with primer pairs AVP1-F and AVP1-R, PP2A-C5-F and PP2A-C5-R, and ACTIN-F and ACTIN-R (Supplementary Table S1). Randomly selected transgenic plants transformed with vector A were subjected to northern blotting44 (primer pairs AVP1-F1 and AVP1-R1, C5fullF and C5FullR, and ACT2fullF and ACT2FullR; see Supplementary Table S1) to verify the RT-qPCR results.

Statistical analyses

The relative transcript levels of PP2A-C5 and AVP1 in six groups of transgenic plants were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22. The mean values, medians and quantiles were compared and Wilcoxon rank test was used to analyze the significant differences at the significance level p<0.05. The single-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine the data’s consistency with a Normal distribution. Fisher’s Z is used to constructs the 95% confidence intervals to compare the correlation coefficients.

References

De Block, M., Herrera-Estrella, L., Van Montagu, M., Schell, J. & Zambryski, P. Expression of foreign genes in regenerated plants and in their progeny. Embo Journal 3, 1681–1689 (1984).

Apse, M. P., Aharon, G. S., Snedden, W. A. & Blumwald, E. Salt Tolerance Conferred by Overexpression of a Vacuolar Na+/H+ Antiport in Arabidopsis. Science 285, 1256–1258 (1999).

Jaglo-Ottosen, K. R., Gilmour, S. J., Zarka, D. G., Schabenberger, O. & Thomashow, M. F. Arabidopsis CBF1 overexpression induces COR genes and enhances freezing tolerance. Science 280, 104 (1998).

Thomashow, M. F. Plant cold acclimation: Freezing tolerance genes and regulatory mechanisms. Annual Review of Plant Biology 50, 571–599 (1999).

Kasuga, M., Liu, Q., Miura, S., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. & Shinozaki, K. Improving plant drought, salt, and freezing tolerance by gene transfer of a single stress-inducible transcription factor. Nature Biotechnology 17, 287–291 (1999).

Kasuga, M., Miura, S., Shinozaki, K. & Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. A Combination of the Arabidopsis DREB1A Gene and Stress-Inducible rd29A Promoter Improved Drought- and Low-Temperature Stress Tolerance in Tobacco by Gene Transfer. Plant & Cell Physiology 45, 346–350 (2004).

Capell, T. & Christou, P. Progress in plant metabolic engineering. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 15, 148–154 (2004).

Fraley, R. T. et al. Expression of bacterial genes in plant cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 80, 4803–4807 (1983).

Lin, L., Liu, Y. G., Xu, X. P. & Li, B. J. Efficient linking and transfer of multiple genes by a multigene assembly and transformation vector system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100, 5962–5967 (2003).

Goossens, R. & Van Ranst, E. The use of remote sensing to map gypsiferous soils in the Ismailia Province (Egypt). Geoderma 87, 47–56 (1998).

Gaxiola, R. A. et al. Drought- and salt-tolerant plants result from overexpression of the AVP1 H+-pump. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98, 11444–11449 (2001).

Gaxiola, R. A., Fink, G. R. & Hirschi, K. D. Genetic manipulation of vacuolar proton pumps and transporters. Plant Physiology 129, 967–973 (2002).

Randhawa, G., Chhabra, R. & Singh, M. PCR based detection of genetically modified tomato with AVP1D gene employing seed sampling strategy. Seed Science & Technology 39(112–124), 113 (2011).

Arif, A., Zafar, Y., Arif, M. & Blumwald, E. Improved growth, drought tolerance, and ultrastructural evidence of increased turgidity in tobacco plants overexpressing Arabidopsis vacuolar pyrophosphatase (AVP1). Molecular Biotechnology 54, 379–392 (2013).

Pasapula, V. et al. Expression of an Arabidopsis vacuolar H+-pyrophosphatase gene (AVP1) in cotton improves drought- and salt tolerance and increases fibre yield in the field conditions. Plant Biotechnology Journal 9, 88–99 (2011).

Li, J. S. et al. Arabidopsis H+-PPase AVP1 regulates auxin-mediated organ development. Science 310, 121–125 (2005).

Shen, G. X. et al. Co-overexpression of AVP1 and AtNHX1 in Cotton Further Improves Drought and Salt Tolerance in Transgenic Cotton Plants. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 33, 1–11 (2014).

Hu, R. B. et al. Overexpression of PP2A–C5 that encodes the catalytic subunit 5 of protein phosphatase 2A in Arabidopsis confers better root and shoot development under salt conditions. Plant Cell & Environment 40 (2016).

Jones, J. D. G., Gilbert, D. E., Grady, K. L. & Jorgensen, R. A. T-DNA structure and gene expression in petunia plants transformed by Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 derivatives. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 207, 478–485 (1987).

Peach, C. & Velten, J. Transgene expression variability (position effect) of CAT and GUS reporter genes driven by linked divergent T-DNA promoters. Plant Molecular Biology 17, 49–60 (1991).

Lee, H. Y. & Khosla, C. Bioassay-Guided Evolution of Glycosylated Macrolide Antibiotics in Escherichia coli. Plos Biology 5, e45–e45 (2007).

Pehlivan, N. et al. Co-overexpressing a Plasma Membrane and a Vacuolar Membrane Sodium/Proton Antiporter Significantly Improves Salt Tolerance in Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants. Plant and Cell Physiology 57, 1069–1084 (2016).

Kristensen, C. et al. Metabolic engineering of dhurrin in transgenic Arabidopsis plants with marginal inadvertent effects on the metabolome and transcriptome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102, 1779–1784 (2005).

Kim, Y. W., Hirai, T., Kato, K., Hiwasa-Tanase, K. & Ezura, H. Gene dosage and genetic background affect miraculin accumulation in transgenic tomato fruits. Plant Biotechnology 27, 333–338 (2010).

Barolo, S., Carver, L. A. & Posakony, J. W. GFP and beta-galactosidase transformation vectors for promoter/enhancer analysis in Drosophila. Biotechniques 29, 726–732. (2000).

Valenzuela, L. & Kamakaka, R. T. Chromatin insulators. Annual Review of Genetics 40, 107–138 (2006).

Riethoven, J. J. M. Regulatory Regions in DNA: Promoters, Enhancers, Silencers, and Insulators. Methods in Molecular Biology 674, 33–42 (2010).

She, W. J. et al. The gypsy insulator of Drosophila melanogaster, together with its binding protein suppressor of Hairy-wing, facilitate high and precise expression of transgenes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 185, 1141–1150, https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.110.117960 (2010).

Clough, S. J. & Bent, A. F. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Journal for Cell & Molecular Biology 16, 735–743 (1998).

Butaye, K. M. J. et al. Stable high‐level transgene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana using gene silencing mutants and matrix attachment regions. Plant Journal for Cell & Molecular Biology 39, 440–449 (2004).

De Bolle, M. F. C. et al. The influence of matrix attachment regions on transgene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana wild type and gene silencing mutants. Plant Molecular Biology 63, 533–543 (2007).

De Paepe, A. et al. High frequency of single-copy T-DNA transformants produced by floral dip in CRE-expressing Arabidopsis plants. Plant Journal 59, 517–527 (2009).

Engels, C. et al. Introduction of the rd29A:AtDREB2A CA gene into soybean (Glycine max L. Merril) and its molecular characterization in leaves and roots during dehydration. Genetics & Molecular Biology 36, 556–565 (2013).

Ito, Y. et al. Functional analysis of rice DREB1/CBF-type transcription factors involved in cold-responsive gene expression in transgenic rice. Plant & Cell Physiology 47, 141–153 (2006).

Lee, S. C., Huh, K. W., An, K., An, G. & Kim, S. R. Ectopic expression of a cold-inducible transcription factor, CBF1/DREB1b, in transgenic rice (Oryza sativa L.). Molecules & Cells 18, 107–114 (2004).

Dhadi, S. R., Krom, N. & Ramakrishna, W. Genome-wide comparative analysis of putative bidirectional promoters from rice, Arabidopsis and Populus. Gene 429, 65–73 (2009).

Chen, W. H., de Meaux, J. & Lercher, M. J. Co-expression of neighbouring genes in Arabidopsis: separating chromatin effects from direct interactions. Bmc Genomics 11, 178 (2009).

Gdula, D. A., Gerasimova, T. I. & Corces, V. G. Genetic and molecular analysis of the gypsy chromatin insulator of Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93, 9378–9383 (1996).

Bell, A. C., West, A. G. & Felsenfeld, G. Insulators and Boundaries: Versatile Regulatory Elements in the Eukaryotic Genome. Science 291, 447–450 (2001).

Kuhn, E. J. & Geyer, P. K. Genomic insulators: connecting properties to mechanism. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 15, 259–265 (2003).

Murashige, T. & Skoog, F. A Revised Medium for Rapid Growth and Bio Assays with Tobacco Tissue Cultures. Physiologia Plantarum 15, 473–497 (1962).

Topfer, R., Matzeit, V., Gronenborn, B., Schell, J. & Steinbiss, H. H. A set of plant expression vectors for transcriptional and translational fusions. Nucleic Acids Research 15, 5890 (1987).

Golemis, E., Gyuris, J., Chertkov, H. & Brent, R. Cloning vector pJG4-5 (pB42AD), complete sequence (1997).

Sambrook, J. F. & Russell, D. W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual(Third Edition). (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2001).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a scholarship from the China Scholarship Council to Weijia Jiang, and grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China to Yun Zhao and the USDA-Ogallala Aquifer Program and Cotton Incorporated to Hong Zhang.We also thank The Council of Higher Education of Turkey for supporting Necla Pehlivan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z., L.S., W.J. and Y.Z. conceived and designed the experiments; L.S., M.W., N.E., W.J. and X.Y. performed the experiments; M.W. and W.J. analyzed the data; H.Z., L.S., R.Z. and Y.Z. and contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; H.Z., M.W., N.P., W.J., X.Y., L.S. and Y.Z. wrote the paper. The work has not been submitted elsewhere for publication, and all the authors listed have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Access number: Sequence data used in the article were obtained from GenBank with accession numbers NM_105665.3 (PP2A-C5), NM_101437.5 (AVP1), AF242365.2(gypsy insulator).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, W., Sun, L., Yang, X. et al. The Effects of Transcription Directions of Transgenes and the gypsy Insulators on the Transcript Levels of Transgenes in Transgenic Arabidopsis. Sci Rep 7, 14757 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15284-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15284-x

This article is cited by

-

Mutational analysis identifies functional Rap1, Su(Hw), and CTCF insulator sites in Arabidopsis thaliana

Plant Cell Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.