Abstract

Carbon material containing nickel, nitrogen and sulfur (Ni-NSC) has been synthesized using metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) as precursor by annealing treatment with a size from 200 to 300 nm. Pd nanoparticles supported on the Ni-NSC (Pd/Ni-NSC) are used as electrocatalysts for ethanol oxidation in alkaline media. Due to the synergistic effect between Pd and Ni, S, N, free OH radicals can form on the surface of Ni, N and S atoms at lower potentials, which react with CH3CO intermediate species on the Pd surface to produce CH3COO− and release the active sites. On the other hand, the stronger binding force between Pd and co-doped N and S is responsible for enhancing dispersion and preventing agglomeration of the Pd nanoparticles. The Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC shows better electrochemical performance of ethanol oxidation than the traditional commercial Pd(20 wt%)/C catalyst. Onset potential on the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC electrode is 36 mV more negative compared with that on the commercial Pd(20 wt%)/C electrode. The Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC in this paper demonstrates to have excellent electrocatalytic properties and is considered as a promising catalyst in alkaline direct ethanol fuel cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fuel cells are widely recognized as very attractive devices to obtain directly electric energy through an electrochemical reaction between anode and cathode1. Among the power sources, direct methanol fuel cells (DMFCs) have been extensively investigated and proposed to be used as mobile applications2. Compared to methanol, ethanol is a promising alternative fuel with less toxicity. Direct ethanol fuel cells (DEFCs) have been extensive studied by many research groups3,4,5,6. As emerging technologies, DEFCs have many challenges that need to be addressed. One of the major hurdles of the DEFCs is the ethanol electrooxidation reaction which exists slow sluggish kinetics due to the twelve-electron transfer process7,8. Platinum (Pt) and Pt-based nanoparticles have been generally used as the acceptable anode materials for the electrooxidation of liquid fuels such as methanol and ethanol9,10,11. Unfortunately, high cost and susceptible to poisoning by CO make it practically impossible to be an ideal candidate at a commercial level. Therefore, exploring cost-effective and catalytically active materials is of great interest to study.

Compared with Pt, palladium (Pd) has numerous advantages in the DEFCs9,10,12,13,14,15. Xu and Shen9,16 firstly found that Pd-based catalysts have remarkable activity for ethanol oxidation in alkaline media in 2006. However, it is still necessary to decrease the dosage of Pd and lower the catalyst cost. Lots of methods have been proposed such as modifying Pd particles with transition metal oxides including NiO, MnO2, MoO3, CeO2, Co3O4, CuO and TiO2 10,16,17,18,19. Among such transition metal oxides, NiO nanoparticles can improve the oxidation kinetics and reduce the poisoning of Pd/C, due to the excellent capacity to transport surface lattice oxygen and OHads 10,20,21. However, general routes to synthesize NiO nanoparticles are usually on the surface of carbon materials, which lead to heterogeneous dispersion and even result in the surface shed off. Thus, it is urgent to choose a template to arrange the growth of transition metal oxides. Recently, porous carbon materials synthesized by directly annealing coordination compounds especially metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) possess ultrahigh surface area and periodic network of highly ordered three-dimensional framework structure, which are highly desirable as stable supports to load precious metals22,23,24,25.

Here, we used the vanillic thiosemicarbazone ligand (L = C9H10N3O2S) including N and S heteroatoms and its coordination compound NiL2 as precursors to obtain porous carbon materials containing nickel, nitrogen and sulfur (Ni-NSC), which can be easily synthesized. Through carbonization and doping steps, the Pd nanoparticles supported on the Ni-NSC (Pd/Ni-NSC) can be successfully obtained. The as-prepared porous Pd/Ni-NSC materials will be used as catalysts for ethanol electrooxidation. Zhong et al. have studied the PdNi/C nanoparticles by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and revealed the presence of metallic Ni and the oxide phases NiO, Ni(OH)2, NiOOH in the catalyst matrix21. So PdNi materials have been used as electrocatalysts for the ethanol oxidation reaction in alkaline media14,26,27. Niu et al.28 have reported that small palladium nanoparticles (Pd NPs) inside sulfur-doped carbon microsphere (S-CMS) show both high electrocatalytic activity and long durability for methanol oxidation reaction (MOR) in the DMFCs. Wei et al. have studied the interaction between nitrogen in the carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and Pd in the catalysts29. The nitrogen-doped CNTs-supported Pd catalysts exhibit superior electrochemical activity for ethanol oxidation relative to the pristine CNTs. Zhang et al.30 have reported that the introduced nitrogen and sulfur co-doping could generate abundant active sites on the graphene surface supported Pd nanoparticles (Pd/NS-rGO) and the Pd/NS-rGO catalyst also reveals superior anti-poisoning ability and amazing stability.

Results and Discussion

XRD patterns for the Ni-NSC and Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC were presented in Fig. 1a. All the characteristic peaks could be well observed corresponding to the standard patterns of NiCx, Ni4N and Pd (JCPDS card No. 45–0979, 36–1300 and 65–2867). The diffraction peaks around 48.6, 55.0 and 76.0° were assigned to the (200), (210) and (300) facets of the cubic crystallite Ni4N. The strong diffraction peaks at the Bragg angles of 40.1, 46.6, 68.1, 82.1 and 86.6° correspond to the (111), (200), (220), (311) and (222) facets of the face-centered cubic crystallite Pd. The diffraction peaks associated with Ni4N derived from Ni compound in the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC composite show weaker peaks in comparison with the signal of Ni-NSC unloading Pd. Raman measurements of Ni-NSC and Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC further confirm the structural composition as shown in Fig. 1b. The characteristic D and G bands of graphitic carbon can be seen at 1340 and 1589 cm−1 in both two materials, which could be assigned to the defective and graphitic structure of the carbon materials31. D band arises from disordered sp3 defect sites and is also associated with defects and disorder in carbon structure32. The degree of graphitization of carbon materials can be quantified by the intensity ratio of D to G bands. In this case, those defects will in turn act as active sites and reinforce the interaction between Pd particles and support, and thus increase the catalysts loading and particles dispersion. The I D/I G ratio of Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC is 1.05, which is smaller than that of Ni-NSC(1.11). It may be attributable to the supporting Pd, which can decrease defect sites and disorder in carbon structure.

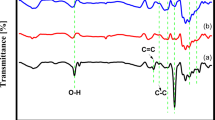

The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra in Fig. 2 confirm various surface groups of Ni-NSC. The peaks at 3570 cm−1 in the spectra should be considered as the O-H stretching vibration. The peak at 1755 cm−1 is attributed to the C=C and C=N stretching vibration in the conjugated structure33. In addition, two obvious peaks at 2414 and 2389 cm−1 in the spectrum of Ni-NSC should be ascribed to the –N=C=O and -N-C-S stretching vibration, respectively. It indicates that the N and S atoms have been doped to the Ni-NSC. The absorbance from 970 to 1200 cm−1 is attributed to the stretching vibrations of the C-O-C and C-S-C bond34. Besides, the bending vibration of the C-S bond also shows a weak peak at 646 cm−1, which confirms the successful doping of sulfur element. Moreover, surface groups of Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC compared with that of Ni-NSC in FTIR spectra have a weaker peak, which is due to Pd nanoparticles growing on the Ni-NSC surface and weakening the absorption intensity.

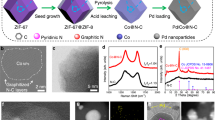

Chemical bonding states in the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC were analyzed by XPS (Fig. 3). From the compared survey of Ni-NSC and Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC shown in Fig. 3a, the peaks are corresponding to existence of Pd 3d, Ni 2p, C 1 s, N 1 s and S 2p, respectively. Ni 2p spectrum presents a complicated structure with two strong satellite peaks adjacent to the main peaks as shown in Fig. 3b, which is due to multi-electron excitation. The presence of multiple-valence nickel element in the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC is apt to occur redox reaction due to electron transfer. The binding energy values of XPS spectrum of Pd 3d display a doublet that is composed of a low-energy band (Pd 3d5/2) and a high-energy band (Pd 3d3/2) at 335.4 and 340.7 eV (Fig. 3c), which are similar to the typical Pd0 specie as previous report35. These above data show that Pd specie attached to the surface of Ni-NSC exists in the form of Pd0. From the high resolution peak split in Fig. 3d, the C 1 s spectrum is deconvoluted into four peaks, sp2-hybridized graphite-like carbon C=C at 284.6 eV, sp3-hybridized diamond-like carbon C-C at 285.2 eV, C−O−C/C-N bond at 286.2 eV and O=C–O bond at 288.1 eV36. The high resolution N 1 s spectrum in Fig. 3e can be resolved into four sub-peaks due to the spin–orbit coupling, including pyridinic-N (398.5 eV), pyrrolic-N (399.7 eV), graphitic-N (400.7 eV) and pyridine-N-oxide groups (401.7 eV)37. Besides, the S 2p spectrum can be deconvoluted to one pair of spin-orbit doublet at 161.0 (S 2p3/2) and 162.9 eV (S 2p5/2) in Fig. 3f, indicating the existence of metal sulfide and formation of C-S-C at 164.1 eV37. These results of the existence of mentioned-above chemical bonds illustrate that Ni, N and S atoms are doped well into the carbon material to form Ni-NSC, in which Pd nanoparticles are inserted.

The as-synthesized microporous Ni-NSC and Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC materials were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Fig. 4a,b). It is found that the size of the Ni-NSC and Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC particles is both ranged from 200 to 300 nm. The typical transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images for Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC are shown in Fig. 4c,d. It is clearly observed that deep shadow particles on microporous Ni-NSC known as Pd nanoparticles exhibit a spherical-like shape with well-dispersion. As shown in Fig. 4e, it clearly reveals a lattice spacing of 0.218 and 0.221 nm, which correspond to the distance of the (111) crystal plane of Ni4N and the (204) one of NiCx. Besides, one lattice fringe measured from the image can be found around 0.226 nm, which corresponds to the distance of the (111) crystal plane of Pd. Figure 4f is the selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern of Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC, where a series of well-defined rings can be assigned to Ni4N(111), NiCx(204) and Pd(111). Elemental mapping results (Fig. 4g–k) confirm the presence of Pd, Ni, C, N and S components in Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC. All the results show that the elements of Pd, Ni, C, N and S can be observed, indicating their coexistence in the catalysts.

For the purpose of comparison, commercial Pd(20 wt%)/C from Sigma-Aldrich was also investigated. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements for ethanol electrooxidation on the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC and commercial Pd(20 wt%)/C electrodes were carried out in 1.0 mol L−1 KOH containing 1.0 mol L−1 ethanol solution with a sweep rate of 50 mV s−1 at a Pd loading of 0.10 mg cm−2 to evaluate their electrocatalytical activity as shown in Fig. 5. The background is the CV on the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC electrode measured in a nitrogen-saturated 1.0 mol L−1 KOH solution without ethanol. The magnitude of oxidation current on the forward scan indicates the activity of electrocatalyst for ethanol oxidation, which is corresponding to the oxidation of freshly chemisorbed species from ethanol adsorption. As shown in the inset figure of Fig. 5, the Ni-NSC shows poor performance for ethanol oxidation. Compared with the CV in the absence of ethanol, an ethanol oxidation peak can be clearly observed in the CV curve on the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC electrode in the presence of 1.0 mol L−1 ethanol. It is obviously that the activity of ethanol oxidation on the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC electrode is much higher than that on the commercial Pd(20 wt%)/C electrode. The onset potential (E s) is −0.628 V on the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC electrode, which is 36 mV more negative compared with that on the commercial Pd(20 wt%)/C electrode (−0.592 V). The lower value of E s shows easier electrooxidation of ethanol. The current for ethanol electrooxidation on the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC electrode begins to rise much more sharply at more negative potential than that on the commercial Pd(20 wt%)/C electrode. It demonstrates that ethanol can be more easily electrochemically oxidized on the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC electrode than that on the commercial Pd(20 wt%)/C electrode. The peak current density (j p ) is 110.3 mA cm−2 (−0.293 V) on the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC electrode, which is 2.6 times as high as that on the commercial Pd(20 wt%)/C electrode, which is 41.8 mA cm−2 (−0.316 V). Current density at the potential of 0.3 V (j −0.3V) is 108.1 mA cm−2 on the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC electrode, which is 2.8 times as high as that on the commercial Pd(20 wt%)/C electrode, which is 38.0 mA cm−2.

In addition, the compared Tafel plots of ethanol electrooxidation, calculated from the quasi-steady-state curve obtained in 1.0 mol L−1 KOH containing 1.0 mol L−1 ethanol solution with a sweep rate of 2 mV s-1 at a Pd loading of 0.10 mg cm−2, show linear region with the respective Tafel slope of 190.24 mV dec-1 on the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC electrode and 244.21 mV dec−1 on the commercial Pd(20 wt%)/C electrode as shown in Fig. 6. The Tafel value on the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC electrode is lower than that on the commercial Pd(20 wt%)/C electrode, which shows that ethanol oxidation occurs favourably on the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC electrode. In ethanol electrooxidation controlled by the adsorption of OHads, the expected Tafel slope is 120 mV dec-1 and a positive deviation may be explained by the formation of an inactive oxide layer on the palladium surface and by the 2D structure of the catalytic layer38.

To further evaluate the electrocatalyst stability, the method of chronoamperometry for ethanol oxidation in 1.0 mol L−1 KOH solution containing 1.0 mol L−1 ethanol at −0.3 V was taken as shown in Fig. 7. It is well-known that the intermediate species such as CO-like species during alcohol oxidation will block the electrode surface to poison the catalyst, then the current of alcohol oxidation will decrease39. Nevertheless, at the end of the test, the oxidation current density is 2.5 mA cm−2 on the Pd(20 wt%)/Ni-NSC electrode which is larger than that on the commercial Pd(20 wt%)/C electrode (1.8 mA cm−2). The good stability of Pd/Ni-NSC catalyst could be relevant with well-dispersed Pd particles, the stronger binding force between Pd and co-doped N and S to inhibit agglomeration of particles29,30. It is generally considered that co-doped two-types N and S are responsible for the interaction with metal catalysts and prevent them from aggregation together30,40.

The ethanol electrooxidation on Pd-based electrocatalysts is as following step26,30:

The reaction (4) is the rate-determining step.

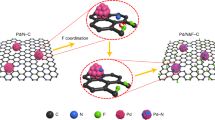

The (CH3CO)ads is adsorbed onto the surface of the Pd and it can block the active sites and slows the reaction kinetics. The ethanol oxidation on the Pd/NS-rGO may be explained as a bi-functional mechanism10,41. Density functional theory calculations reveal that the improved activity and stability stems from the promoted production of free OH radicals (OHads, on Ni active sites) which facilitate the oxidative removal of carbonaceous poison and combination with CH3CO radicals on adjacent Pd active sites14. The electron-accepting N and S species can impart a relatively high positive charge density on neighboring OH− in the alkaline media, the OHads species can be more easy formed on the surface of N or S atoms than that on the surface of Pd at lower potentials as following reactions.

The reaction (6) happens more easily than reaction (4). Pd acts as main catalyst for catalysing the dehydrogenation of ethanol during the oxidation reaction and free OH radicals (OHads) can form on the N or S atoms surface at lower potentials. These oxygen containing species react with (CH3CO)ads intermediate species on the Pd surface to produce CH3COO− and release the active sites. On the other hand, the introduction of N and S atoms significantly changes the electronic structure of carbon materials and the supported Pd nanoparticle. Therefore, due to the electrondonating effects of N and S atoms, the electron cloud density of Pd may increase, which can stabilize Pd, and the N and S groups impart a basic nature to the carbon surface and bind strongly to Pd, enhancing the Pd nanoparticls dispersion and preventing agglomeration of the Pd particles, thereby improving the electrochemical activity and stability of the Pd-based catalysts29,42.

In summary, highly active Pd/Ni-NSC materials obtained by heating method and chemical reduction from vanillic thiosemicarbazone ligand (L = C9H10N3O2S) and its coordination compound NiL2 as precursors to obtain porous carbon materials have been successfully developed and demonstrated as excellent catalysts for efficient ethanol electrooxidation in alkaline media. Thanks to the synergistic effect between Pd and Ni, S, N, free OH radicals can form on the surface of Ni, N and S atoms at lower potentials, which react with (CH3CO)ads intermediate species on the Pd surface to produce CH3COO− and release the active sites. On the other hand, the electrondonating effects of N and S atoms enhance dispersion and prevent agglomeration of the Pd nanoparticls. The Pd/Ni-NSC shows extraordinary catalytic activity and stability for electrochemical oxidation of ethanol, more competitive than those of the traditional commercial Pd/C catalyst. This work provides new insights into using transition metal oxide and renewable carbon materials as high performance electrocatalyst for alkaline DEFCs.

Methods

Materials synthesis

All reagents were of commercially available and analytical grade (AR). All chemicals were purchased from Aladdin and used as received. Vanillin thiosemicarbazone ligands, Ni-vanillic thiosemicarbazone were synthesized according to the literature40. Ni-NSC materials were prepared by pyrolyzing the obtained NiL2 composite. In a typical procedure, a ceramic boat containing Ni-NSC (500 mg) was placed in a quartz tube, heated under N2 atmosphere at a ramping rate of 3 °C min−1, and kept at 500 °C for 2 h. Pd/Ni-NSC was prepared by reduction Pd(NH3)4Cl2 on the Ni-NSC powders using an excess 0.01 mol L−1 NaBH4 solution. The ratio of Pd and Ni-NSC was controlled by stoichiometric calculation with the same weight ratio of commercial Pd/C as 20 to 80.

Characteriazation

XRD was carried out using a X’Pert powder X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm). Raman spectra were obtained using laser confocal micro-Raman spectroscopy (LabRAM HR800, Horiba Jobin Yvon). FTIR spectra were collected using a Tensor27 (Bruker) spectrometer. XPS measurements were performed in an ESCALAB 250 spectrometer under vacuum (about 2 × 10−9 mbar). Field-emission SEM images were conducted on a Quanta 400 FEG microscope (FEI Company). TEM images corresponding element energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) were carried out on a JEOL JEM-2010 (JEOL Ltd.). All electrochemical measurements were tested in a three-electrode cell using a CHI 760e electrochemical work station at 25 °C. Solutions were freshly prepared before each experiment. A platinum foil (3.0 cm2) was used as counter electrode. All the potentials were measured versus a saturated calomel electrode (SCE, 0.241 V vs. NHE) electrode. CV data were recorded between −0.95 to 0.40 V with a scan rate at 50 mV s−1.

References

Dunn, B., Kamath, H. & Tarascon, J. M. Electrical energy storage for the grid: A battery of choices. Science 334, 928–935 (2011).

Lu, Y. X., Du, S. F. & Robert, S. W. One-dimensional nanostructured electrocatalysts for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells—A review. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 199, 292–314 (2016).

Zakil, F. A., Kamarudin, S. K. & Basri, S. Modified Nafion membranes for direct alcohol fuel cells: An overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 65, 841–852 (2016).

Akhairi, M. A. F. & Kamarudin, S. K. Catalysts in direct ethanol fuel cell (DEFC): An overview. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 41, 4214–4228 (2016).

Ye, S. H., Feng, J. X. & Li, G. R. Pd Nanoparticle/CoP nanosheet hybrids: Highly electroactive and durable catalysts for ethanol electrooxidation. ACS Catal. 6, 7962–7969 (2016).

Diab, H. et al. Longitudinal hierarchy Co3O4 mesocrystals with high-dense exposure facets and anisotropic interfaces for direct-ethanol fuel cells. Sci. Rep. 6, 24330, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24330 (2016).

Kim, I. et al. Catalytic reactions in direct ethanol fuel cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 50, 2270–2274 (2011).

Liang, Z. X., Zhao, T. S., Xu, J. B. & Zhu, L. D. Mechanism study of the ethanol oxidation reaction on palladium in alkaline media. Electrochim. Acta 54, 2203–2208 (2009).

Xu, C. W., Cheng, L. Q., Shen, P. K. & Liu, Y. L. Methanol and ethanol electrooxidation on Pt and Pd supported on carbon microspheres in alkaline media. Electrochem. Commun. 9, 997–1001 (2007).

Xu, C. W., Shen, P. K. & Liu, Y. L. Ethanol electrooxidation on Pt/C and Pd/C catalysts promoted with oxide. J. Power Sources 164, 527–531 (2007).

Wang, A. L., Liang, C. L., Lu, X. F., Tong, Y. X. & Li, G. R. Pt–MoO3–RGO ternary hybrid hollow nanorod arrays as high-performance catalysts for methanol electrooxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A. 4, 1923–1930 (2016).

Bianchini, C. & Shen, P. K. Palladium-based electrocatalysts for alcohol oxidation in half cells and in direct alcohol fuel cells. Chem. Rev. 109, 4183–206 (2009).

Wang, H., Jiang, K., Chen, Q. L., Xie, Z. X. & Cai, W. B. Carbon monoxide mediated chemical deposition of Pt or Pd quasi-monolayer on Au surfaces with superior electrocatalysis for ethanol oxidation in alkaline media. Chem. Commun. 52, 374–377 (2016).

Chen, L. et al. Improved ethanol electrooxidation performance by shortening Pd–Ni active site distance in Pd–Ni–P nanocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 8, 14136, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14136 (2017).

Ding, L. X. et al. Hierarchical Pd-Sn alloy nanosheet dendrites: An economical and highly active catalyst for ethanol electrooxidation. Sci. Rep. 3, 1181, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01181 (2013).

Shen, P. K. & Xu, C. W. Alcohol oxidation on nanocrystalline oxide Pd/C promoted electrocatalysts. Electrochem. Commun. 8, 184–188 (2006).

Xu, W., Zhu, S. L., Li, Z. Y., Cui, Z. D. & Yang, X. J. Evolution of palladium/copper oxide-titanium dioxide nanostructures by dealloying and their catalytic performance for methanol electro-oxidation. J. Power Sources 274, 1034–1042 (2015).

Liu, Q. et al. Manganese dioxide coated graphene nanoribbons supported palladium nanoparticles as an efficient catalyst for ethanol electrooxidation in alkaline media. Electrochim. Acta 203, 91–98 (2016).

Qin, Y. H. et al. Enhanced electrocatalytic activity and stability of Pd nanoparticles supported on TiO2-modified nitrogen-doped carbon for ethanol oxidation in alkaline media. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 42, 1103–1112 (2017).

Dutta, A. & Datta, J. Energy efficient role of Ni/NiO in PdNi nano catalyst used in alkaline DEFC. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 3237–3250 (2014).

Zhong, J. T. et al. Highly active and durable flowerlike Pd/Ni(OH)2 catalyst for the electrooxidation of ethanol in alkaline medium. RSC Adv. 6, 72722–72727 (2016).

Gokhale, R., Chen, Y. C., Serov, A., Artyushkova, K. & Atanassov, P. Novel dual templating approach for preparation of highly active Fe-N-C electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction. Electrochim. Acta 224, 49–55 (2017).

Xia, W., Mahmood, A., Zou, R. Q. & Xu, Q. Metal–organic frameworks and their derived nanostructures for electrochemical energy storage and conversion. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 1837–1866 (2015).

Salunkhe, R. R. et al. Asymmetric supercapacitors using 3D nanoporous carbon and cobalt oxide electrodes synthesized from a single metal-organic framework. ACS Nano 9, 6288–6296 (2015).

Wang, T. C. et al. Ultrahigh surface area zirconium MOFs and insights into the applicability of the BET theory. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 3585–3591 (2015).

Jiang, R. Z., Tran, D. T., McClure, J. P. & Chu, D. A class of (Pd−Ni−P) electrocatalysts for the ethanol oxidation reaction in alkaline media. ACS Catal. 4, 2577–2586 (2014).

Lee, K. et al. One-pot synthesis of monodisperse 5 nm Pd−Ni nanoalloys for electrocatalytic ethanol oxidation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4, 4208–4214 (2012).

Niu, X. H. et al. Highly active and durable methanol electro-oxidation catalyzed by small palladium nanoparticles inside sulfur-doped carbon microsphere. Fuel 190, 174–181 (2017).

Wei, Y. et al. Nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube-supported Pd catalyst for improved electrocatalytic performance toward ethanol electrooxidation. Nano-Micro. Lett. 9, 28, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-017-0129-5 (2017).

Zhang, J. X. et al. Microwave-assisted synthesis of Pd oxide-rich Pd particles on nitrogen/sulfur co-doped graphene with remarkably enhanced ethanol electrooxidation. Fuel Cells 17, 115–122 (2017).

Kim, U. J., Furtado, C. A., Liu, X. M., Chen, G. G. & Eklund, P. C. Raman and IR spectroscopy of chemically processed single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 15437–15445 (2005).

Zhao, Y., Yang, X. & Tian, J. Electrocatalytic oxidation of methanol at 2-aminophenoxazin-3-one-functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes supported PtRu nanoparticles. Electrochim. Acta 54, 7114–7120 (2009).

Liu, J. Q. et al. Multifunctional N, S co-doped carbon quantum dots with pH- and thermo-dependent switchable fluorescent properties and highly selective detection of glutathione. Carbon 104, 169–187 (2016).

Qu, K. G., Zheng, Y. & Qiao, S. Z. Graphene oxide-polydopamine derived N, S-codoped carbon nanosheets as superior bifunctional electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction and evolution. Nano Energy 19, 373–381 (2016).

Paredis, K. et al. Evolution of the structure and chemical state of Pd nanoparticles during the in situ catalytic reduction of NO with H2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 13455–13464 (2011).

Li, X. Z. et al. MOF derived Co3O4 nanoparticles embedded in N doped mesoporous carbon layer/MWCNT hybrids: Extraordinary bi-functional electrocatalysts for OER and ORR. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 17392–17402 (2015).

Qiu, Y., Huo, J. J., Jia, F., Brent, H. S. & Li, W. Z. N- and S-doped mesoporous carbon as metal-free cathode catalysts for direct biorenewable alcohol fuel cells. J. Mater. Chem. A. 4, 83–95 (2016).

Ghosh, S. et al. Conducting polymer-supported palladium nanoplates for applications in direct alcohol oxidation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 40, 4951–4959 (2015).

Zhang, J. H. et al. CeO2 promoted Au/C catalyst for glycerol electro-oxidation in alkaline medium. J. Energy Inst. 89, 325–329 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Palladium nanoparticles supported on nitrogen and sulfur dual-doped graphene as highly active electrocatalysts for formic Acid and methanol oxidation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 10858–10865 (2016).

Xu, C. W., Tian, Z. Q., Shen, P. K. & Jiang, S. P. Oxide (CeO2, NiO, Co3O4 and Mn3O4)-promoted Pd/C electrocatalysts for alcohol electrooxidation in alkaline media. Electrochim. Acta 53, 2610–2618 (2008).

Jin, H. et al. Improved electrocatalytic activity for ethanol oxidation by Pd@N-doped carbon from biomass. Chem. Commun. 50, 12637–12640 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2014A030313521 and 2014A030313529), Scientific Research Foundation for Yangcheng Scholar (1201561607), Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (201510010112).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.W.X. designed the experiments. Z.R.Y. And S.Q.W. performed the experiments, A.J.Z. supervised the experiments, C.W.X. and J.W. collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. J.W. gave suggestion to revise the manuscript. All authors analyzed data, discussed the results, and reviewed the manuscript. All the authors have equal contribution in this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, ZR., Wang, SQ., Wang, J. et al. Pd supported on carbon containing nickel, nitrogen and sulfur for ethanol electrooxidation. Sci Rep 7, 15479 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15060-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15060-x

This article is cited by

-

Partial oxidation of methane over biomass fly ash (BFA)-supported Ni/CaO catalyst for hydrogen-rich syngas production

Research on Chemical Intermediates (2022)

-

Fabrication of Composite Material with Pd Nanoparticles and Graphene on Nickel Foam for Its Excellent Electrocatalytic Performance

Electrocatalysis (2020)

-

Improved electrochemical performance of supercapacitors by utilizing ternary Pd-AC-doped NiO nanostructure as an electrode material

Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry (2020)

-

Simple synthesis of N-doped catalysts with controllable Pt–Ni nanoparticles for high-efficiency ethanol oxidation

Ionics (2019)

-

Voltammetric determination of vitamin B2 by using a highly porous carbon electrode modified with palladium-copper nanoparticles

Microchimica Acta (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.