Abstract

Spin-dependent energy bands and transport properties of ferromagnetic-strain graphene superlattices are studied. The high spin polarization appears at the Dirac points due to the presence of spin-dependent Dirac points in the energy band structure. A gap can be induced in the vicinity of Dirac points by strain and the width of the gap is enlarged with increasing strain strength, which is beneficial for enhancing spin polarization. Moreover, a full spin polarization can be achieved at large strain strength. The position and number of the Dirac points corresponding to high spin polarization can be effectively manipulated with barrier width, well width and effective exchange field, which reveals a remarkable tunability on the wavevector filtering behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graphene has attracted enormous attention from experimentalists and theorists since its discovery. In particular, the high carrier mobility and small spin-orbit coupling in graphene make it very promising for applications in nanoelectronics and spintronics. Recently, it is theoretically predicted that1,2 depositing a ferromagnetic insulator (FI) such as EuO on graphene can induce an exchange proximity interaction1,3, and the exchange proximity interaction can be treated as an effective exchange field (EEF). The deposition of EuO on graphene has been experimentally realized and its proximity induced ferromagnetization has been confirmed4. Many theoretical works on spin transport through ferromagnetic graphene suggest that the spin current can be controlled by gate voltages1,2,5, magnetic barriers6,7, and local strain8,9,10. Particularly, Dell’Anna found that an inhomogeneous perpendicular magnetic field together with a strong in-plane spin splitting can produce a wavevector-dependent spin-filtering effect6. Zhai showed that ferromagnetic graphene junctions with a modulated substrate strain can achieve a strain-tunable spin current8. Recently, Wu has examined that the ferromagnetic graphene system combined with strain or Rashba spin-orbit coupling, or both, can induce a spin band gap and achieve complete spin polarization10.

At the same time, graphene superlattices with electrostatic potential or magnetic barrier have also received broad theoretical and experimental investigations11,12,13,14,15,16. In electrostatic potential graphene superlattices, a new Dirac point appears in the band structures13,14 and it’s exactly located at zero-averaged wave number (zero-\(\bar{k}\))15. The zero-\(\bar{k}\) gap associated with this new Dirac point is insensitive to both lattice constant and structural disorder, resulting in more controllable electronic transport in graphene superlattices. Extra Dirac points in the band structure at zero-\(\bar{k}\) have been experimentally observed14,17,18. As a comparison, in magnetic graphene superlattices, new finite-energy Dirac points are generated in the band structure and the Fermi velocity at zero energy Dirac points is isotropically renormalized19,20,21. Recently, resonant tunneling in ferromagnetic graphene superlattices has been studied and its splitting in the transmission gap can be used to generate an efficient wavevector filter22. However, ferromagnetic graphene superlattices alone cannot suppress the spin-dependant Klein tunneling23, which results in finite spin polarization.

In addition, the pseudo magnetic field induced by the strain is an efficient method to suppress Klein tunneling10,23, and a local strain can be achieved by patterning grooves, creases, steps, or wells in the substrate where graphene rests24,25,26, so that different regions of the substrate interact differently with the graphene sheet, generating different strain profiles27. Evidence for strain-induced spatial modulations in the local conductance of graphene on SiO2 substrates has already been reported in experiment28. Building from these literature works, we now consider a ferromagnetic-strain graphene superlattice, where the spin-dependant Klein tunneling is violated. We first discuss the zero-\(\bar{k}\) and finite-energy Dirac points’ locations in the spectrum of a ferromagnetic graphene superlattices in detail. When strain is also considered, we observe that a band gap is induced in the vicinity of finite-energy Dirac points, and the band gaps for spin-up and spin-down electrons are present in different energy regions. The spin-dependent band structure is clearly reflected in the transport properties, which provides a guide for enhancing the spin polarization. The position and number of Dirac points, and the corresponding high spin polarization, can be effectively manipulated by adjusting the barrier width, well width and EEF strength, which demonstrates remarkable tunability on the wavevector filtering behavior.

The paper is organized as follows. In Sec. II, we present the theoretical formalisms and the dispersion relations. The numerical results on band structures and transmission for different spins are shown in Secs. III. Finally, we draw conclusions in Sec. IV.

Computational Models and Methods

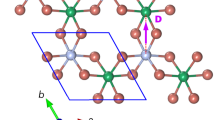

Let us consider a one-dimensional ferromagnetic-strained superlattice in graphene formed by a series of EEF barriers and strained barriers. In our case, we consider a series of FI strips with z-axis magnetizations deposited periodically on the top of graphene to induce the EEF barriers1,3. It has been demonstrated that the EEF between electrons in graphene and localized electrons in an adjacent FI layer is about 5 meV1 and can be further enhanced by applying an external electric field perpendicular to the graphene sheet3. In this paper, the local strains are assumed inside these FI stripe regions, which can be induced by a tension along the y direction applied on the substrate rather than the graphene. It is known that graphene can sustain elastic up to 25%29,30. The elastic deformation can be treated as a perturbation to the hopping amplitudes and acts as a pseudogauge potential A s (r)31,32. Here the pseudogauge potential is induced by the uniaxial strain. As a corollary, the pseudogauge potential is a finite and constant, which is defined as As(r) = As(x) = tβε(1 + σ)33, and σ = 0.165 is the Poisson’s ratio of graphite, t is the nearest-neighbour hopping parameter, and ε is the tensile strain. The constant β = ∂lnt/∂lnδ, where δ is the distance between nearest carbon atoms. Several units of such structures are depicted in Fig. 1, and the length of each unit is L = d 1 + d 2. The low-energy effective Hamiltonian for ferromagnetic-strain graphene can be written as

where v F ≈ 106 m/s is the Fermi velocity, τ z = ±1 for K and K ' valleys, σ i and s i (i = x, y, z) are the Pauli matrices acting on the sublattice (A, B) and physical spin (↑, ↓) spaces, respectively. Due to the translational invariance in the y direction, the wave function in the j th ferromagnetic-strained barrier can be presented as \(\tilde{{\rm{\Psi }}}={\rm{\Psi }}(x){e}^{i{k}_{y}x}\) with

where \({k}_{j}=\tfrac{(E-s{M}_{j})}{(\hbar {v}_{F})}\) (s = ±1 for spin-up and spin-down electrons) and k yj = k y + τ z (A sj )/(ħv F ). k y = (Esinθ 0)/(ħv F ), θ 0 is the incident angle. q j = sign (k j ) (k j 2 − k yj 2)1/2 for k j 2 > k yj 2, otherwise q j = sign(k j ) i(k yj 2 − k j 2)1/2, and a j (b j ) is the amplitude of the forward (backward) propagating wave. For the well region, the above equations are still valid and only require that M j = 0 and A sj = 0. Inside the same barrier or well region, the wave functions at any two positions x and x + Δx can be related via the transfer matrix16

with θ j = arcsin(kyj/kj). Furthermore, the overall T-matrix for the N regions is simply a product of matrices:

Here the w j is the width of the jth potential region. And we can connect the input and output wave functions by the relation: Ψ(x N ) = XΨ(x 0), where the Ψ(x N ) and Ψ(x 0) can be written as:15

and

Here, θ N is the exit angle at the exit end, Ψ i (E, k y ) is the incident wave packet of the electron, \({r}_{s,{\tau }_{z}}\) is the spin/valley resolved reflection coefficient and t s,τz is the spin/valley resolved transmission coefficient, respectively. Solving the above two equations, we find the r s,τz and t s,τz can be given

Once the transmission coefficient is obtained, the spin/valley resolved conductance G s,τz of the system at zero temperature is written as G s,τz = G 0∫0 (π)/(2) T s,τz cosθ 0 dθ 0, where T s,τz = |t s,τz 2|, G 0 = 2e 2 mv F L y /ħ 2 and L y is the width of the graphene stripe in the y direction. Meanwhile, the spin polarizations are defined as

Schematic illustration of the Ferromagnetic-strained graphene superlattices produced by a series of FM stripes and substrate strains. W is the width of the graphene sample in the y direction. The length of one unit is L = d 1 + d 2, d 1 is the width of the Ferromagnetic-strained graphene, d 2 is the width of the normal graphene.

Results and Discussion

In order to understand the transport properties, it is instructive to first investigate the electronic band structure for the ferromagnetic-strain graphene supperlatice. According to the Bloch’s theorem15, the electronic dispersion for any transversal wave number follows the relation:

Here K s,τz is Bloch wave vector. Γ1 and Γ2 are the transfer matrixes for one barrier and one well, respectively. q 1 = sign(E − sM)\(\sqrt{{(\tfrac{E-{}_{s}M}{\hslash {v}_{F}})}^{2}\,-\,{({k}_{y}+{\tau }_{z}\tfrac{{A}_{s}}{\hslash {v}_{F}})}^{2}}\) for \({(\frac{E-sM}{\hslash vF})}^{2} > {({k}^{y}+{\tau }_{z}\tfrac{As}{\hslash {v}_{F}})}^{2}\), otherwise \({q}_{1}={\rm{sign}}(E-sM)i\) \(\sqrt{{({k}_{y}+{\tau }_{z}\tfrac{{{\rm{A}}}_{s}}{\hslash {v}_{F}})}^{2}-{(\tfrac{E-sM}{\hslash {v}_{F}})}^{2}}\). \({q}_{2}={\rm{sign}}(E)\sqrt{\tfrac{{E}^{2}}{{(\hslash {v}_{F})}^{2}}+{k}_{y}^{2}}\,{\rm{for}}\,\tfrac{{E}^{2}}{{(\hslash {v}_{F})}^{2}} > {{k}_{y}}^{2}\), otherwise \({q}_{2}={\rm{sign}}(E)i\sqrt{{k}_{y}^{2}-\tfrac{{E}^{2}}{{(\hslash {v}_{F})}^{2}}}\). Using |cos(K s,τz L)| ≤ 1, we can find the real solution of \({K}_{s,{\tau }_{z}}\) for passing band s . Otherwise, the non-existence of real \({K}_{s,{\tau }_{z}}\) indicates a band gap34.

Now let us use the above equations to calculate the electronic band structures under different strain strength. The transmissions of electrons in K and K ' valleys show mirror symmetry10,23, so we focus only on the spin transport for the valley K. When A s = 0 (Fig. 2a,d), we find that the zero-\(\bar{k}\) Dirac point is given at \(E=\frac{sM}{2}\), k y = 0. When strain is considered (Fig. 2b,c,e,f), we find that the zero-\(\bar{k}\) Dirac point is shifted to \({k}_{y}=-\frac{{A}_{s}}{2\hslash {v}_{F}}\) along \(E=\frac{sM}{2}\). Here \(\hslash {v}_{F}=(\frac{4.14\times {10}^{-12}}{2\pi }\,{\rm{meV}}\cdot {\rm{s}})\,({10}^{15}\,{\rm{nm}}/{\rm{s}})=\frac{2070}{\pi }\,{\rm{meV}}\cdot {\rm{nm}}\). In other words, the Dirac point shifts to \({k}_{y}=-\frac{{A}_{s}}{2\hslash {v}_{F}}\) in k space, but the energy is invariable. Such a result can be solved by the dispersion relation of Eq. (6).

Electronic band structures for up spin (a–c) and down spin (d–f) with different strain strength: (a) and (d) A s = 0 meV; (b) and (e) A s = 20 meV; (c) and (f) A s = 60 meV; The dotted lines denote the centre position of the zero-averaged wave number Dirac point. The round dashed lines denote the centre position of the finite-energy Dirac points. The other parameters are M = 40 meV, d 1 = d 2 = 20 nm.

Applying the implicit function theorem, the gradient of the dispersion relation will be zero only if sin(q 1 d 1) = sin(q 2 d 2) = 0 and cos(q 1 d 1) = cos(q 2 d 2) = 1. When A s = 0, the following equations are satisfied

Here m, n are integers. The equation (6) shows that cos(K s,τz L) = cos(q 1 d 1 ± q 2 d 2) for k y = 0 and A s = 0, which indicates that K s,τz always has real solutions for any E and M; that is, the location of the crossing point of the bands exactly appears at k y = 0. So under the condition of k y = 0 and A s = 0, one can get \(E=\tfrac{sM{d}_{1}}{{d}_{1}+{d}_{2}}+\hslash {v}_{F}{\rm{\pi }}\tfrac{m+n}{{d}_{1}+{d}_{2}}\). If the condition q 1 d 1 =− q 2 d 2 = mπ is satisfied, the solution is \(E=\tfrac{sM{d}_{1}}{{d}_{1}+{d}_{2}}\), which is the so-called zero-\(\bar{k}\) Dirac point15. Further when d 1 = d 2, the zero-\(\bar{k}\) Dirac point is located at \(E=\tfrac{sM}{2}\), k y = 0. This way, we can also locate the other crossing points corresponding to the finite-energy Dirac points20, at \(E=\tfrac{sM{d}_{1}}{{d}_{1}+{d}_{2}}\) + \(\hslash {v}_{F}\pi \frac{l}{{d}_{1}+{d}_{2}}\)(l = ±1, ±2 \(\cdots \)) and k y = 0. From Fig. 2a,d, one can observe that the finite-energy Dirac points for the spin-up (spin-down) band is exactly located in E = 71.15 meV, −31.15 meV, −81.15 meV (81.15 meV, 31.15 meV, −71.15 meV). Moreover, Fig. 2a,d also suggest that the spin-up and spin-down Dirac points don’t always coincide, which plays a key role in spin-dependent transport, but it is noted that the bands always cross at k y = 0.

In addition, if A s ≠ 0, one can find

When q 1 d 1 =− q 2 d 2 = mπ is also satisfied, we can get

The equation (9) is tenable under the conditions Ed 1 − sMd 1 =−Ed 2 and k y d 1 + \(\frac{{A}_{s}}{\hslash {v}_{F}}\) d 1 = −k y d 2, so E = \(\frac{sM{d}_{1}}{{d}_{1}+{d}_{2}}\), \({k}_{y}=-\tfrac{As{d}_{1}}{\hslash {v}_{F}({d}_{1}+{d}_{2})}\) is one solution of Eq. (9), which corresponds to the zero-\(\bar{k}\) Dirac point. If d 1 = d 2, zero-\(\bar{k}\) Dirac point is located at \(E=\tfrac{sM}{2}\), \({k}_{y}=-\tfrac{As}{2\hslash {v}_{F}}\). However, it is more difficult to find analytic solutions of the finite-energy Dirac points like the analytic results obtained by solving Eq. (7). But numerical calculations show that the finite-energy Dirac points are strongly affected by the strain strength. Due to the effects of strain, the finite-energy Dirac points are not only shifted in energy but also decreased in number (Fig. 2b,e), even disappear completely for large strain strengths (Fig. 2c,f). Then, there emerges an energy gap in the vicinity of the vanished finite-energy Dirac points with further increasing the strain strength. And the energy gaps for the spin-up and spin-down bands don’t fully overlap. These characters mean that the increasing of A s may be used to enhance the spin polarization in ferromagnetic-strain graphene superlattices.

The above discussions on the band structures should be helpful for understanding the spin-dependent transport. Figure 3 displays the spin-dependent transmission T s , spin-dependent conductance G s and spin polarization along z direction P z of the ferromagnetic-strain graphene superlattices under different strain. Here we only consider A s = 0 and A s = 60 meV, and take the superlattice period number n = 10. In the absence of strain (Fig. 3a,b), the transmission shows a spin-dependent Klein tunneling and embodies the mirror symmetry about θ = 0. But the transmission for up-spins is different from that for down-spins, especially at the locations of the Dirac points where the transport channels for up-(down-) spins are finite, while the transport channels for down-(up-) spins are large. These characters ensure that the two spin conductance channels are obviously different at these Dirac points (as seen in Fig. 3e), and finite spin polarization appears (as seen in Fig. 3(g)). When strain is considered (Fig. 3c,d), we find that the mirror symmetry with θ = 0 is destroyed because of the shifted Dirac points by the strain, and the spin-dependent Klein tunneling is suppressed due to the spin-dependent band gap induced by the strain. It is noted that the spin-dependent transmission gaps also induce zero-\(\bar{k}\) Dirac points nearby because the spin-dependent waves inside the potential barrier are evanescent waves when the relation \({(E-sM)}^{2} < {({k}_{y}+{\tau }_{z}{A}_{s})}^{2}\) is satisfied. Then we find that the spin-up and spin-down conductances are totally different around those disappeared Dirac points. Especially, in the vicinity of E = 20 meV, 71.15 meV (E =−20 meV, −71.15 meV), the spin-depended conductance G ↓ (G ↑) shows a broad peak, while G ↑ (G ↓) approaches zero (Fig. 3f), so fully spin polarized plateaus with large spin-polarized currents are achieved around these Fermi energies (as seen in Fig. 3g). In addition, spin polarization oscillations are obtained as seen in Fig. 3g, which can be used as a spin switch by modulating the Fermi energy.

(a–d) Spin-dependent transmission T s with different strain strength (a) and (b) A s = 0 meV, (c) and (d) A s = 60 meV versus Fermi energy and incident angle; (e and f) spin-dependent conductance G s and (g) spin polarization P z versus Fermi energy. the periodic number N = 10, and M = 40 meV, d 1 = d 2 = 20 nm.

The above discussions show that high spin polarizations always appear in the vicinity of the vanished Dirac points. And the positions of Dirac points in (E, k y ) space can be controlled by the barrier and well widths. Figure 4a–c show the band structures with different barrier and well widths. The locations of the zero-\(\bar{k}\) Dirac points move towards E = 0 and k y = 0 with gradually reduced d 1/(d 1 + d 2) ratio at fixed heights of potentials. The locations of the band gaps around the vanished finite-energy Dirac points move toward E = 0 too. In addition, the number of band gaps increases with the increase of the lattice constant d 1 + d 2. The reason of that is the zero-\(\bar{k}\) Dirac points is exactly located \(E=\tfrac{sM{d}_{1}}{{d}_{1}+{d}_{2}}\), \({k}_{y}=-\tfrac{As{d}_{1}}{{d}_{1}+{d}_{2}}\), which is determined by the d 1/(d 1 + d 2) ratio. The finite-energy Dirac points are located at \(E=\tfrac{sM{d}_{1}}{{d}_{1}+{d}_{2}}+\hslash {v}_{F}{\rm{\pi }}\tfrac{l}{{d}_{1}+{d}_{2}}\), which depends not only on the d 1/(d 1 + d 2) ratio but also the lattice constant d 1 + d 2. So we can modulate the location and number of high spin polarization regions by adjusting the the d 1/(d 1 + d 2) ratio and the lattice constant.

(a–c) Electronic band structures for up spin and down spin for M = 40 meV with different barrier and the well width: (a) d 1 = d 2 = 30 nm; (b) d 1 = 20 nm, d 2 = 40 nm; (c) d 1 = 20 nm, d 2 = 60 nm; (d–f) spin-dependent conductance G s and spin polarization P z versus Fermi energy with the periodic number N = 10 corresponds to the cases in (a–c).

Next we consider the spin-dependent conductance G s (Fig. 4d–f) and spin polarization P z (Fig. 4h–r) of an electron passing through the ferromagnetic-strain graphene superlattices with different width. Comparison between Fig. 4a–f indicates that the distribution of transmission spectra is completely consistent with the band structures, that is, strong transmission regions correspond to the transmission bands and forbidden transmission regions correspond to the band gaps. Then, the location of high spin polarization approaches E = 0 with the decrease of d 1/(d 1 + d 2) ratio, and the number of high spin polarization regions increases with increasing lattice constants (Fig. 4h–r). Therefore the increase of lattice constants makes the spin polarization oscillations more obvious.

In addition, the height of potentials can also affect the locations of the Dirac points. Figure 5a shows the spin polarization with respect to M and E for d 1 = d 2 = 20 nm. In the absence of EEF, the spin polarization is zero (Fig. 5a) due to the spin degeneracy (as seen in Fig. 5b). And the spin polarization initially increases and then decreases with increasing the EEF strength for M ≥ A s (Fig. 5a). The reason is that when the EEF strength M ≥ A s , the gaps around the Dirac points are finite (as seen in Fig. 5c,d) and the crossing points even reappear for larger M (as seen in Fig. 5e,f), which leads to both up-spins and down-spins having transport channels around the Dirac points therefore the spin polarization is reduced. So too large M does not guarantee effective spin filtering in such ferromagnetic-strain graphene superlattices. We also find that the high spin polarization regions are shifted away from zero energy owing to the shift of Dirac points away from E = 0 with the increasing of EEF.

(a) spin polarization P z versus Fermi energy and exchange field strength with the periodic number N = 10, (b–f) Electronic band structures for up spin and down spin with different exchange field strength: (a) M = 0 meV; (c) and (d) M = 60 meV; (e and f) M = 80 meV; The other parameters are d 1 = d 2 = 20 nm, A s = 60 meV.

Summary

In summary, we studied the spin-dependent band structures and transport properties of graphene under a periodic effective exchange field and strain, where the spin-dependant Klein tunneling is disrupted. We discussed the zero wave number Dirac points’ and finite-energy Dirac points’ locations on the spectra of ferromagnetic graphene superlattices in detail. The spin-up and spin-down Dirac points are present on the energy spectra alternately, which results in finite spin polarization. When strain is considered, band gaps are induced around the finite-energy Dirac points, and high spin polarization is achieved in the vicinity of these Dirac points. The position, and number of the Dirac points can be effectively manipulated by adjusting the barrier width, well width and EEF strength, which leads to tunable spin polarization. We hope these results are helpful for understanding the electronic properties for spin transports and can offer guidance to potential applications of the spin filtering devices.

References

Haugen, H., Huertas-Hernando, D. & Brataas, A. Spin transport in proximity-induced ferromagnetic graphene. Phys. Rev. B 77, 115406 (2008).

Yang, H. X. et al. Proximity effects induced in graphene by magnetic insulators: First-principles calculations on spin filtering and exchange-splitting gaps. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 046603 (2013).

Semenov, Y., Kim, K. & Zavada, J. Spin field effect transistor with a graphene channel. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 153105 (2007).

Swartz, A. G., Odenthal, P. M., Hao, Y., Ruoff, R. S. & Kawakami, R. K. Integration of the ferromagnetic insulator euo onto graphene. ACS Nano 6, 10063–10069 (2012).

Yokoyama, T. Controllable spin transport in ferromagnetic graphene junctions. Phys. Rev. B 77, 073413 (2008).

Dell’Anna, L. & De Martino, A. Wave-vector-dependent spin filtering and spin transport through magnetic barriers in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 80, 155416 (2009).

Khodas, M., Zaliznyak, I. A. & Kharzeev, D. E. Spin-polarized transport through a domain wall in magnetized graphene. Phys. Rev. B 80, 125428 (2009).

Zhai, F. & Yang, L. Strain-tunable spin transport in ferromagnetic graphene junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 062101 (2011).

Niu, Z. Spin and valley dependent electronic transport in strain engineered graphene. J. Appl. Phys. 111, 103712 (2012).

Wu, Q.-P., Liu, Z.-F., Chen, A.-X., Xiao, X.-B. & Liu, Z.-M. Generation of full polarization in ferromagnetic graphene with spin energy gap. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 252402 (2014).

Marchini, S., Günther, S. & Wintterlin, J. Scanning tunneling microscopy of graphene on ru(0001). Phys. Rev. B 76, 075429 (2007).

Vázquez de Parga, A. L. et al. Periodically rippled graphene: Growth and spatially resolved electronic structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 056807 (2008).

Barbier, M., Vasilopoulos, P. & Peeters, F. M. Dirac electrons in a kronig-penney potential: Dispersion relation and transmission periodic in the strength of the barriers. Phys. Rev. B 80, 205415 (2009).

Brey, L. & Fertig, H. A. Emerging zero modes for graphene in a periodic potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 046809 (2009).

Wang, L.-G. & Zhu, S.-Y. Electronic band gaps and transport properties in graphene superlattices with one-dimensional periodic potentials of square barriers. Phys. Rev. B 81, 205444 (2010).

Zhao, P.-L. & Chen, X. Electronic band gap and transport in fibonacci quasi-periodic graphene superlattice. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 182108 (2011).

Park, C.-H., Yang, L., Son, Y.-W., Cohen, M. L. & Louie, S. G. Anisotropic behaviours of massless dirac fermions in graphene under periodic potentials. Nat. Phys. 4, 213–217 (2008).

Yankowitz, M. et al. Emergence of superlattice dirac points in graphene on hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Phys. 8, 382–386 (2012).

Tan, L. Z., Park, C.-H. & Louie, S. G. Graphene dirac fermions in one-dimensional inhomogeneous field profiles: Transforming magnetic to electric field. Phys. Rev. B 81, 195426 (2010).

Dell’Anna, L. & De Martino, A. Magnetic superlattice and finite-energy dirac points in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 83, 155449 (2011).

Le, V. Q., Pham, C. H. & Nguyen, V. L. Magnetic kronig–penney-type graphene superlattices: finite energy dirac points with anisotropic velocity renormalization. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 24, 345502 (2012).

Lu, W.-T., Li, W., Wang, Y.-L., Jiang, H. & Xu, C.-T. Tunable wavevector and spin filtering in graphene induced by resonant tunneling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 062108 (2013).

Zhang, Y.-T. & Zhai, F. Strain enhanced spin polarization in graphene with rashba spin-orbit coupling and exchange effects. J. Appl. Phys. 111, 033705 (2012).

Li, X., Wang, X., Zhang, L., Lee, S. & Dai, H. Chemically derived, ultrasmooth graphene nanoribbon semiconductors. Science 319, 1229–1232 (2008).

Low, T. & Guinea, F. Strain-induced pseudomagnetic field for novel graphene electronics. Nano Lett. 10, 3551–3554 (2010).

Lu, J., Neto, A. C. & Loh, K. P. Transforming moiré blisters into geometric graphene nano-bubbles. Nat. Commun. 3, 823 (2012).

Pereira, V. M. & Castro Neto, A. H. Strain engineering of graphene’s electronic structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 046801 (2009).

Teague, M. et al. Evidence for strain-induced local conductance modulations in single-layer graphene on sio2. Nano Lett. 9, 2542–2546 (2009).

Lee, C., Wei, X., Kysar, J. W. & Hone, J. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science 321, 385–388 (2008).

Kim, K. S. et al. Large-scale pattern growth of graphene films for stretchable transparent electrodes. Nature 457, 706–710 (2009).

Pereira, V. M., Castro Neto, A. H. & Peres, N. M. R. Tight-binding approach to uniaxial strain in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 80, 045401 (2009).

Fujita, T., Jalil, M. & Tan, S. Valley filter in strain engineered graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 043508 (2010).

Liu, Z.-F. et al. Helical edge states and edge-state transport in strained armchair graphene nanoribbons. Sci. Rep. 7, 8854 (2017).

Fan, X., Huang, W., Ma, T., Wang, L.-G. & Lin, H.-Q. Electronic band gaps and transport properties in periodically alternating mono-and bi-layer graphene superlattices. EPL 112, 58003 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 11764013, 11364019, 11464011, 11365009 and 11664019), the China Scholarship Council (File NOs 201509795008 and 201509795010), the Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars in Jiangxi Province (Grant No. 2016BCB23032) and NSERC Discovery grant RGPIN-418415 and RGPIN-04178, and the Canada First Research Excellence Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.P.W. conceived the idea and performed the calculation. Z.F.L., Q.P.W. and G.X.M. contributed to the interpretation of the results and wrote the manuscript. A.X.C. and X.B.X. contributed in the discussion. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, QP., Liu, ZF., Chen, AX. et al. Tunable Dirac points and high spin polarization in ferromagnetic-strain graphene superlattices. Sci Rep 7, 14636 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14948-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14948-y

This article is cited by

-

Biperiodic superlattices and transparent states in graphene

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Valley-Dependent Electronic Transport in a Graphene-Based Magnetic-Strained Superlattice

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2022)

-

Observation of spin-polarized Anderson state around charge neutral point in graphene with Fe-clusters

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.