Abstract

Neurodevelopmental impairment is the most common comorbidity associated with complex congenital heart disease (CHD), while the underlying biological mechanism remains unclear. We hypothesised that impaired cerebral oxygen delivery in infants with CHD is a cause of impaired cortical development, and predicted that cardiac lesions most associated with reduced cerebral oxygen delivery would demonstrate the greatest impairment of cortical development. We compared 30 newborns with complex CHD prior to surgery and 30 age-matched healthy controls using brain MRI. The cortex was assessed using high resolution, motion-corrected T2-weighted images in natural sleep, analysed using an automated pipeline. Cerebral oxygen delivery was calculated using phase contrast angiography and pre-ductal pulse oximetry, while regional cerebral oxygen saturation was estimated using near-infrared spectroscopy. We found that impaired cortical grey matter volume and gyrification index in newborns with complex CHD was linearly related to reduced cerebral oxygen delivery, and that cardiac lesions associated with the lowest cerebral oxygen delivery were associated with the greatest impairment of cortical development. These findings suggest that strategies to improve cerebral oxygen delivery may help reduce brain dysmaturation in newborns with CHD, and may be most relevant for children with CHD whose cardiac defects remain unrepaired for prolonged periods after birth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common congenital disorder in newborns, affecting approximately 1% of births1. Of these, approximately half will have severe or moderately severe forms of CHD that require expert cardiology care at birth2. Survival rates through adolescence have improved dramatically3, and neurodevelopmental impairment has now become the most important comorbidity in this growing population of survivors. Up to half of children with complex CHD experience a distinct pattern of neurodevelopmental and behavioural impairment, characterised by mild cognitive impairment, impaired social and communication skills, inattention, impulsive behaviour and later, impaired executive function4.

Understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying neurodevelopmental delay in this population remains limited. Early animal catheterisation studies suggested that fetal cerebral oxygen delivery is reduced in CHD, particularly in transposition of the great arteries (TGA) and left-sided lesions5. Advances in fetal MRI have since demonstrated a 10% reduction in ascending aortic saturations in a mixed group of CHD6, which may impair normal oligodendrocyte maturation in the developing brain7.

Brain “immaturity” has been described in CHD before surgery8 using a radiologist-graded scoring system9, and has been associated with impaired neurodevelopment at 2 years of age in children with CHD10. An objective marker of the developing brain’s cortical folding is the gyrification index, first described in the context of autopsy specimens11,12, and has been shown to increase markedly over the third trimester and during early infancy13. Gyrification index may be an important metric when studying neurodevelopment in this population: reduced gyrification index of newborns with CHD has been demonstrated in autopsy specimens14, fetal MR imaging studies15, and neonatal MR imaging studies16,17, although all studies to date have required varying degrees of manual input, and neonatal studies to date have not attempted to quantify regional differences or to correlate cortical development with cerebral oxygenation delivery.

We hypothesised that impaired cerebral oxygen delivery (CDO2) in infants with CHD is a cause of impaired cortical development, and predicted that cardiac lesions most associated with most reduced cerebral oxygen delivery would demonstrate the greatest impairment of cortical development. We aimed to compare the cortex of newborns with CHD prior to surgery versus healthy control infants, assessing cortical folding, cortical grey matter volumes and cerebral blood flow calculated from high resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Results

Demographics

There were no significant differences in GA at birth or at scan between newborns with CHD and healthy controls. There were no significant differences in birthweight, birthweight z-score, head circumference at birth, head circumference z-score, and sex between groups. There were no sex-based differences in total grey matter volume, gyrification index, cerebral oxygen delivery or regional cerebral oxygen saturations. A summary of CHD diagnoses can be seen in Table 1.

Cerebral oxygen delivery (CDO2) is positively associated with brain volume and gyrification

Phase contrast measurements, preductal arterial saturations and haemoglobin levels were successfully obtained in 24 of 30 babies with CHD (mean 161, SD 21 g/L). Calculated CDO2 (median 1638 ml O2/min, range 1011–3023 ml O2/min) showed a positive association with total brain volume (R2 = 0.42, p < 0.001), grey matter volume (R2 = 0.48, p < 0.001, Fig. 1a), and whole brain gyrification index (R2 = 0.279, p = 0.008, Fig. 1b). A secondary analysis included days of mechanical ventilation and requirement for prostaglandin E2 in the regression model with no significant effect on the results for brain volume, grey matter volume or gyrification. Indexing CDO2 per unit of brain volume retained the same trends as without indexing, but weakened both the association with grey matter volume (R2 = 0.199, p = 0.029, Fig. 1c) and with gyrification index (R2 = 0.127, p = 0.087, Fig. 1d).

Cerebral oxygen delivery (CDO2) demonstrates a positive association with grey matter volume (a) and whole brain gyrification (b). These trends persist after indexing CDO2 per 100 ml brain volume (c and d). Regional cerebral oxygen saturation has a limited positive relationship with gyrification index (e). Abnormal mixing lesions and left sided lesions demonstrate a significantly lower gyrification index, while right-sided lesions are less affected (f).

To understand the relative contribution of CBF and oxygen saturations to CDO2, we compared correlations between both factors and CDO2 (Supplementary Figure S1). CBF was more strongly correlated with CDO2 (R2 = 0.643, p < 0.001) than arterial saturations (R2 = 0.107, p = 0.119), suggesting that blood flow contributed more to the values seen for CDO2. Subgroup analysis of cerebral haemodynamics by lesion physiology was hampered by small sample sizes, although there was a trend towards higher cerebral blood flows and oxygen delivery in right sided lesions and lower in CHD with abnormal mixing (Supplementary Figure S2).

Regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rScO2) was measured in all 30 babies with CHD. Consecutive repeat measurements were obtained in 24 of the 30 babies, demonstrating good repeatability (linear R2 = 0.86, p < 0.001). rScO2 showed a modest correlation with both whole brain gyrification index (R2 = 0.17, p = 0.023, Fig. 1e), and grey matter volume (R2 = 0.21, p = 0.011).

Cortical volumes are reduced in newborns with CHD

Infants born with CHD had smaller total brain volumes (p < 0.001) and smaller cortical grey matter volumes (p < 0.01). Other brain volumes were also smaller, including deep grey matter (p < 0.001), white matter (p = 0.01), and cerebellar volume (p < 0.001). Ventricular volume was not significantly different between groups (p = 0.09). Extracerebral CSF space was increased in the CHD group (p = 0.011). Volumetric results are summarised in Table 2.

Gyrification index is globally reduced in newborns with CHD

Brain gyrification was reduced in infants with CHD (p < 0.01, Fig. 2a). Regional analysis showed significantly reduced gyrification index in the temporal (p = 0.002), parietal (p = 0.005) and occipital (p = 0.018), and a trend towards reduction in the frontal lobes (p = 0.052). Regional gyrification differences between groups are described in Table 3, with plots displayed in Fig. 2b–e and a visualisation on a representative cortical surface in Fig. 2f.

Gyrification index differences between newborns with complex congenital heart disease (open blue) and healthy controls (solid orange), in the whole brain (a) and exploratory regional analysis (b–e). The cortical surface visualisation (f) demonstrates regions where gyrification is reduced in newborns with congenital heart disease compared to healthy term controls, from the left lateral side (i) and from above (ii); colours represent p values from multivariate general linear models, using postmenstrual age as a covariate; no multiple comparisons correction has been performed in this visualisation.

Gyrification varies between different CHD types

To explore differences further, newborns with CHD were divided into three main physiological groups: 1) Abnormal mixing (i.e. transposition of the great arteries, double-outlet right ventricle), 2) Left sided lesions (i.e. hypoplastic left heart syndrome, coarctation of the aorta), and 3) Right sided lesions (i.e. pulmonary atresia or stenosis), and each group compared to its matched controls. Compared to healthy newborns, gyrification was reduced in mixing (p = 0.011) and left sided lesions (p = 0.019), but not in right sided lesions (p = 0.136) (Fig. 1f).

Requirement for septostomy is not associated with cortical volume and gyrification differences

Infants with TGA required septostomy in 5 of 14 cases (36%). We repeated analyses with this as a co-variate in the statistical analysis and found results were unchanged. Within the TGA group, we compared infants with and without a requirement for septostomy, and found no difference in terms of brain volume (p = 0.825) or gyrification (p = 0.19).

Discussion

Reduced cerebral oxygen delivery in newborns with CHD before surgery is associated with impaired cortical development. Cortical grey matter volumes and gyrification index were lower in newborns with complex CHD when compared to healthy matched controls. The degree of cortical impairment was most significant in mixing and left-sided lesions, which may relate to the fetal cerebral circulatory impairment that has been demonstrated in these groups5,6.

A recent study of a similar number of infants showed reduced CDO2 in newborns with mixed complex CHD compared to controls, with the lowest CDO2 measured in infants with transposition18. Lim and colleagues found that arterial saturations had the greatest influence on CDO2, and that there were no significant CBF differences between CHD and control infants18. We were unable to replicate these findings due to lack of flow measurements in our control group, but our results suggest that CBF had a greater contribution to the variation of CDO2 within our CHD cohort. Ascending aorta oxygen saturations were found to be 10% lower in fetuses with CHD when compared to healthy controls using fetal MRI6. Animal studies have shown that a lower oxygen tension environment affects mechanisms that coordinate myelination and angiogenesis during the early phase of brain development7, and causes diminished proliferation and neurogenesis in the subventricular zone, accompanied by reduced cortical growth19. Taken together with our results, these findings suggest that the developing brain may be adversely affected by the lower oxygen tension environment that is observed in CHD in both fetal and postnatal life.

A limited number of studies have reported altered cortical folding in fetuses and newborns with CHD. An “immature cortical mantle” was first described in an early post-mortem study from a cohort of 41 infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome14. Delayed cortical folding has been described using a radiologist scoring system9 in pre-surgical newborns with CHD, starting at around 30 weeks of gestation8. The same finding in post-surgical infants has been shown to be a strong predictor of later neurodevelopmental outcome10. Specific analysis of the gyrification of the opercula was performed in a cohort of newborns with HLHS and TGA prior to surgery, and demonstrated that opercula in CHD was more “open” and exhibited reduced folding complexity20. Gyrification index in fetuses with HLHS was found to be reduced compared to controls using a semi-automated analysis technique, and these group differences increased progressively with advancing gestational age15. Our study adds weight to these findings in a more diverse group of CHD.

Cortical development follows a predictable timeline13. Most gyri become well defined between 26–28 weeks, becoming more prominent and deeply infolded during the third trimester, with subsequent development of secondary and tertiary gyri21. The frontal third of the brain commences its gyrification slightly before the intermediate and caudal thirds, but also takes longer to reach its adult degree of cortical folding by 48 weeks (compared to 44 and 43 weeks respectively)13. We found that gyrification index in our CHD group was most reduced in parietal and temporal regions, and least in the frontal region. This may be due to later completion of gyrification in the frontal region, but also that the pace of gyrification is greatest in parietal, temporal and occipital regions during the time window of our study13. Impaired gyrification in infants with CHD may therefore be most apparent in these regions.

To understand gyrification differences further, we examined three subgroups using a cardiac physiology-based categorisation: abnormal mixing, left sided lesions. and right sided lesions. We found significant gyrification differences in the abnormal mixing group, but were unable to form strong conclusions from our left- and right-sided lesion groups due to small subgroup numbers. We were unable to study infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome separately, a condition known to impair fetal brain development15. There are limited previous studies for comparison, with no pre-surgical neonatal studies for reference. In a previous study of post-surgical infants with transposition, gyrification was reported to be similar to controls17, which may be explained by smaller group sizes and less closely matched postmenstrual ages at scan. There was unfortunately no control group for their pre-surgery infants for direct comparison.

Our finding of reduced brain volumes in newborns with transposition fits with a recent large population study of 924,422 Dutch liveborn singletons, which found that in contrast to other forms of CHD where both head circumference and birth weight of infants were reduced, only infants with transposition had smaller head circumference relative to birth weight22. Reduced head circumference at birth, the most widely available proxy of impaired fetal brain growth23, has often been reported in CHD, most consistently in HLHS and TGA24,25,26,27, but also in tetralogy of Fallot, ventricular septal defects, common arterial trunk, and anomalous pulmonary venous return22. In contrast to other studies, we found that there was no difference in the z-scores of head circumferences between CHD and healthy groups in our cohort. However, brain volumes were significantly reduced in CHD. The discrepancy between head circumference and brain volume is explained by a larger extra-cerebral CSF volume in the CHD group, in the presence of comparable ventricular volumes.

Brain growth trajectories in CHD have been shown to diverge from healthy fetuses in the third trimester, during a period where there is usually an acceleration of energy-demanding brain growth28, using both fetal ultrasound29 and fetal MRI6,15,28. A limited number of cohorts have also suggested an increased prevalence of ventriculomegaly in fetuses with CHD, as assessed by radiologist assessment30 and two-dimensional measurements31. Increased CSF spaces in CHD has only previously been described in a limited number of studies28,31, and may be a marker of cerebral parenchymal growth disturbance.

Our study has a number of limitations. We did not have phase contrast measurements for our control group, limiting analysis of CDO2 against cortical metrics to those infants with CHD. In addition, our CDO2 measurements were performed shortly following birth, while the majority of brain development until that point occurs in utero with a fetal circulation. Delayed brain growth and maturation is more like to reflect CDO2 in utero, which was not measured in this study. There are many influences on early brain growth, and although currently poorly understood, genetic abnormalities are highly prevalent in the CHD population32. It is logical that smaller brains as a direct result of genetic factors with lower metabolic demands will require less blood flow and oxygen delivery, which may explain part of the association demonstrated in this study. We addressed this by calculating the indexed oxygen delivery per unit of brain tissue, and our results support the contention that CDO2 is reduced even when taking into account differences in brain volume. However, it is not possible to fully determine if lower CDO2 as a result of CHD has resulted in the development of a smaller brain, or if extrinsic factors to this analysis (i.e. genetic) have resulted in smaller brains with smaller metabolic demands that require less CDO2.

Conclusions

Cortical folding and cortical grey matter volume is reduced in newborns with congenital heart disease when compared to healthy matched controls. Lower cerebral oxygen delivery measured in newborns with CHD prior to surgery is associated with reduced cortical grey matter volume and gyrification. This supports the possibility that strategies to improve cerebral oxygen delivery in infants with CHD could modify the derailing trajectory of brain development. Our finding of reduced CDO2 may be of greatest importance for children with CHD whose heart defects remain unrepaired for long periods of time after birth, exacerbating deficits in oxygen and other metabolic substrate supply that may have occurred during the prenatal period, and leading to further decrements in brain growth and development after birth.

Methods

The project was approved by the National Research Ethics Service West London committee (CHD: 07/H0707/105, Controls: 14/LO/1169) and informed written parental consent was obtained prior to imaging. All methods and experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Participants

A prospective cohort of 33 infants born with complex CHD requiring surgery within one year was recruited from the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at St Thomas’ Hospital, London. Two infants were found to have neonatal arterial ischaemic stroke on MRI (left parietal stroke (n = 1) and left frontal stroke (n = 1); both TGA post-septostomy) and were excluded from this analysis. A further infant (TGA) was excluded due to unknown date of last menstrual period and lack of ultrasound dating scan.

We therefore studied 30 infants with CHD, born at a median (range) gestational age (GA) of 38+3 (34+6–40+4) weeks. A group of healthy controls was matched by GA at birth and at scan, contemporaneously recruited from the postnatal ward at St Thomas’ Hospital through the Developing Human Connectome Project33, born at a median (range) GA of 38+6 (35+2–40+6) weeks. The median GA at imaging was 39+2 (37+3–41+4) weeks for the CHD group and 39+1 (36+1–41+6) weeks for the control group.

MR imaging

T2-weighted, T1-weighted and phase contrast angiography MR imaging was performed on a Philips Achieva 3 Tesla system (Best, The Netherlands) with a 32-channel neonatal head coil and neonatal positioning device33, situated on the neonatal intensive care unit at St Thomas’ Hospital, London. All examinations were supervised by a paediatrician experienced in MR imaging procedures. All infants were scanned in natural sleep without sedation. Pulse oximetry, respiratory rate, temperature and electrocardiography were monitored throughout. Ear protection comprised earplugs moulded from a silicone-based putty (President Putty, Coltene Whaledent, Mahwah, NJ, USA) placed in the external auditory meatus, neonatal earmuffs (MiniMuffs, Natus Medical Inc, San Carlos, CA, USA) and an acoustic hood positioned over the shell. All sequences included a 5 second initial slow ramp-up in acoustic noise to avoid eliciting a startle response.

T2-weighted images were acquired using a multi-slice turbo spin echo (TSE) sequence, acquired in two stacks of 2D slices (in sagittal and axial planes), using parameters: TR: 12 s; TE: 156 ms, flip angle: 90°, slice thickness: 1.6 mm acquired with an overlap of 0.8 mm; in-plane resolution: 0.8 × 0.8 mm, scan time: 3:12 min per stack. The T1-weighted volumetric magnetisation prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) acquisition parameters were as follows: TR: 11 ms, TE: 4.6 ms, TI: 713 ms, flip angle: 9°, acquired voxel size: 0.8 × 0.8 × 0.8 mm, FOV: 145 × 145 × 108 mm, SENSE factor: 1.2, scan time: 4:35 min. Quantitative flow imaging was performed using velocity sensitised phase contrast imaging, with a single-slice T1-weighted fast field echo sequence. Scan parameters were: field of view (FOV): 100 × 100 mm2, acquisition resolution: 0.6 × 0.6 × 4.0 mm2, TR: 6.4 ms, TE: 4.3 ms, flip angle: 10°, 20 repetitions, maximal encoding velocity (vENC): 140 cm/s, scan time: 71s.

Structural image reconstruction

T2-weighted images were reconstructed following the scan using a dedicated motion correction algorithm. Retrospective motion-corrected reconstruction34,35 and integration of the information from both acquired orientations36 were used to obtain 0.8 mm isotropic T2-weighted volumes with significantly-reduced motion artefacts.

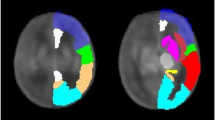

Brain region and tissue segmentation

Motion-corrected T2-weighted images were segmented into tissue type and 87 brain regions using an automated, validated, neonatal-specific pipeline37,38 based on the Expectation–Maximisation (EM) technique39, which was optimised for our acquisition parameters. For more details on the individual parts of the segmentation pipeline, we refer the reader to37,38,40. Each tissue segmentation was manually inspected for accuracy using ITK-SNAP41, and minor corrections performed if necessary.

Gyrification index calculation

Gyrification index was defined as the ratio of the cortical pial surface area and the surface area of the superficial surface enclosing the pial surface12,13,42. This ratio was calculated for each subject using pial surfaces constructed from the combined grey/white matter mask derived from the segmentations, using a previously-published method43, as demonstrated in Fig. 3. Final cortical surfaces were cleaned using median filtering and Laplacian smoothing. The superficial surface was reconstructed using marching cubes from the morphologically closed combined grey/white matter mask. Morphological closing (performed by 3 dilations followed by 2 erosions) removed small sulci and generated a mask that enclosed the original cGM/WM mask. The gyrification index was calculated initially for the whole brain, and then separately for each major brain region (frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital), using appropriate combinations of the 87 segmented brain regions40.

Demonstration of the calculation of gyrification index. (a) Original description of gyrification index in histology setting12, (b) Neonatal brain-extracted T2 volume, (c) Automatic segmentation, (d) Pial surface mesh (green) and superficial surface (red) created from the segmentation, used to calculate the gyrification index. Figure 3a reproduced from The human pattern of gyrification in the cerebral cortex, Zilles, K., Armstrong, E., Schleicher, A. & Kretschmann, H. J. Anat. Embryol. (Berl). 179, 173–179 (1988). Copyright Springer-Verlag 1988. With permission of Springer.

Cerebral blood flow and cerebral oxygen delivery

To calculate cerebral blood flow, we used a previously-published scanning protocol, acquired in a plane perpendicular to both internal carotid and basilar arteries, at the level of the sphenoid bone44, as demonstrated in Fig. 4.

Phase contrast measurements of the cerebral vessels in the neonatal brain. The plane is planned from a 3D non-contrast angiogram in both coronal (a) and sagittal planes (b), aiming for the C4 segment of the internal cerebral arteries (ICA) where all three vessels are running approximately parallel). Following the scan, regions of interest are drawn around the three major cerebral vessels: left (green) and right (red) ICAs, and basilar artery (blue), and these regions are propagated through the cardiac cycle. Flow curves can then be derived across the cardiac cycle (d).

Regions of interest were drawn manually around the three vessels, using Segment v2.0 R480045, and flow curves generated (Fig. 4.). An estimate of total cerebral blood flow (CBF) was calculated from the sum of these vessels. This disregards blood flow to some areas of the cerebellum, which is provided by branches of the vertebral arteries and constitutes less than 3% of the total flow to the brain in healthy adults46.

Haemoglobin (Hb) levels were measured as part of routine clinical care in all patients at a median of 4 days (range 0–10 days) prior to the scan. All newborns with more infrequent Hb monitoring were clinically stable, and we believe all Hb measurements used were representative of levels at time of scan. Arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) was measured at the time of scan using a Masimo Radical-7 monitor (Masimo Corp, Irvine, CA) applied to the right hand.

Cerebral oxygen delivery (CDO2) was calculated using the following formulae47:

where 1.36 is the amount of oxygen bound per gram of haemoglobin at 1 atmosphere (Hüfner’s constant)18.

Regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rScO2)

All newborns had near-infrared spectroscopy rScO2 estimations performed immediately after the scan using a FORE-SIGHT Elite cerebral oxygenation monitor (Casmed, Branford, CT, USA) with neonatal sensor, which was placed over the left frontal region. Measurements were taken for at least three minutes with a sampling frequency of 2 seconds. The output was analysed to obtain mean and standard deviation using a script written in Python (Python Software Foundation, https://www.python.org/). To assess repeatability, the measurement was repeated in a subset of subjects, by disconnecting and removing the sensor from the baby, and reapplying it in a similar location.

Statistical analysis

We automatically matched healthy newborns with babies born with congenital heart disease using an automated method that minimises overall group Euclidean distances between GA and PMA, written in Matlab (R2016, The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, US). We compared group characteristics in newborns with CHD to the healthy control group with the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous data, and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) tests were performed to assess volumetric measurements and gyrification index differences between groups; PMA at scan was included as a covariate. For subsequent regional analyses, outside of the primary hypothesis test, multiple comparisons correction was not performed. Agreement between consecutive readings of rScO2 was analysed using Pearson correlation. Regression analysis was used to compare CDO2 to brain parameters. Z-scores for birth weight and head circumference were calculated using the SITAR R package48, using UK-WHO 2006 population reference data49,50. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics v24 (IBM) and graphs were prepared using R Studio (v1.0.136, RStudio Inc, Boston MA). Three-dimensional visualisations were performed in ParaView51.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

van der Bom, T. et al. The changing epidemiology of congenital heart disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 8, 50–60 (2011).

Hoffman, J. I. E. & Kaplan, S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 39, 1890–1900 (2002).

Wernovsky, G. The paradigm shift toward surgical intervention for neonates with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 162, 849–854 (2008).

Marino, B. S. et al. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Children With Congenital Heart Disease: Evaluation and Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 126, 1143–1172 (2012).

Heymann, M. A. & Rudolph, A. M. Effects of congenital heart disease on fetal and neonatal circulations. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 15, 115–143 (1972).

Sun, L. et al. Reduced Fetal Cerebral Oxygen Consumption is Associated With Smaller Brain Size in Fetuses With Congenital Heart Disease. Circulation 131, 114.013051 (2015).

Yuen, T. J. et al. Oligodendrocyte-encoded HIF function couples postnatal myelination and white matter angiogenesis. Cell 158, 383–96 (2014).

Licht, D., Shera, D. & Clancy, R. Brain maturation is delayed in infants with complex congenital heart defects. J. Thorac. 137, 529-36–7 (2009).

Childs, A. M. et al. Cerebral maturation in premature infants: quantitative assessment using MR imaging. AJNR. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 22, 1577–1582 (2001).

Beca, J. et al. New White matter brain injury after infant heart surgery is associated with diagnostic group and the use of circulatory arrest. Circulation 127, 971–979 (2013).

Elias, H. & Schwartz, D. Surface areas of the cerebral cortex of mammals determined by stereological methods. Science 166, 111–113 (1969).

Zilles, K., Armstrong, E., Schleicher, A. & Kretschmann, H. J. The human pattern of gyrification in the cerebral cortex. Anat. Embryol. (Berl). 179, 173–179 (1988).

Armstrong, E., Schleicher, A., Omran, H., Curtis, M. & Zilles, K. The ontogeny of human gyrification. Cereb. Cortex 5, 56–63 (1995).

Glauser, Ta, Rorke, L. B., Weinberg, P. M. & Clancy, R. R. Congenital brain anomalies associated with the hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatrics 85, 984–990 (1990).

Clouchoux, C. et al. Delayed cortical development in fetuses with complex congenital heart disease. Cereb. Cortex 23, 2932–43 (2013).

Ortinau, C. et al. Cortical folding is altered before surgery in infants with congenital heart disease. J. Pediatr. 163, 1507–10 (2013).

Claessens, N. H. P. P. et al. Delayed cortical gray matter development in neonates with severe congenital heart disease. Pediatr. Res. 80, 668–674 (2016).

Lim, J. M. et al. Cerebral oxygen delivery is reduced in newborns with congenital heart disease. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 152, 1095–103 (2016).

Morton, P. D. et al. Abnormal neurogenesis and cortical growth in congenital heart disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaah7029 (2017).

Awate, S. P., Yushkevich, P., Song, Z., Licht, D. & Gee, J. C. Multivariate high-dimensional cortical folding analysis, combining complexity and shape, in neonates with congenital heart disease. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics) 5636 LNCS, 552–563 (2009).

Chi, J. G., Dooling, E. C. & Gilles, F. H. Gyral development of the human brain. Ann. Neurol. 1, 86–93 (1977).

Matthiesen, N. B. et al. Congenital Heart Defects and Indices of Fetal Cerebral Growth in a Nationwide Cohort of 924 422 Liveborn Infants. Circulation 133, 566–575 (2016).

Cooke, R. W. I., Lucas, A., Yudkin, P. L. N. & Pryse-Davies, J. Head circumference as an index of brain weight in the fetus and newborn. Early Hum. Dev. 1, 145–149 (1977).

Shillingford, A. J. et al. Aortic morphometry and microcephaly in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Cardiol. Young 17, 189–195 (2007).

Rosenthal, G. L. Patterns of prenatal growth among infants with cardiovascular malformations: possible fetal hemodynamic effects. Am. J. Epidemiol. 143, 505–513 (1996).

Donofrio, M. T. et al. Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in fetuses with congenital heart disease: the brain sparing effect. Pediatr. Cardiol. 24, 436–43 (2003).

Limperopoulos, C. et al. Neurologic Status of Newborns With Congenital Heart Defects Before Open Heart Surgery. Pediatrics 103, 402–408 (1999).

Limperopoulos, C. et al. Brain volume and metabolism in fetuses with congenital heart disease: Evaluation with quantitative magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Circulation 121, 26–33 (2010).

Zeng, S. et al. Volume of intracranial structures on three-dimensional ultrasound in fetuses with congenital heart disease. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 46, 174–181 (2015).

McConnell, J. R. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain in infants and children before and after cardiac surgery. A prospective study. Am. J. Dis. Child. 144, 374–8 (1990).

Brossard-Racine, M. et al. Prevalence and spectrum of in utero structural brain abnormalities in fetuses with complex congenital heart disease. AJNR. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 35, 1593–9 (2014).

Blue, G. M. et al. Advances in the Genetics of Congenital Heart Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 69, 859–870 (2017).

Hughes, E. et al. A dedicated neonatal brain imaging system. Magn. Reson. Med. 0, 1–11 (2016).

Cordero-Grande, L. et al. Sensitivity Encoding for Aligned Multishot Magnetic Resonance Reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 2, 266–280 (2016).

Cordero-Grande, L., Hughes, E. J., Hutter, J., Price, A. N. & Hajnal, J. V. Three-dimensional motion corrected sensitivity encoding reconstruction for multi-shot multi-slice MRI: Application to neonatal brain imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. Early view (2017).

Kuklisova-Murgasova, M., Quaghebeur, G., Rutherford, M. A., Hajnal, J. V. & Schnabel, J. A. Reconstruction of fetal brain MRI with intensity matching and complete outlier removal. Med. Image Anal. 16, 1550–1564 (2012).

Makropoulos, A. et al. Automatic Whole Brain MRI Segmentation of the Developing Neonatal Brain. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 62, 1–16 (2014).

Makropoulos, A. et al. Regional growth and atlasing of the developing human brain. Neuroimage 125, 456–478 (2016).

Van Leemput, K., Maes, F., Vandermeulen, D. & Suetens, P. Automated model-based bias field correction of MR images of the brain. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 18, 885–896 (1999).

Makropoulos, A., Robinson, E. C. & Schuh, A. The Developing Human Connectome Project : a Minimal Processing Pipeline for Neonatal Cortical Surface Reconstruction. bioRxiv 1–43 (2017).

Yushkevich, P. A. et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: Significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage 31, 1116–1128 (2006).

Luders, E. et al. A curvature-based approach to estimate local gyrification on the cortical surface. Neuroimage 29, 1224–1230 (2006).

Schuh, A. et al. A deformable model for the reconstruction of the neonatal cortex. in IEEE 14th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) (2017).

Varela, M., Groves, A. M., Arichi, T. & Hajnal, J. V. Mean cerebral blood flow measurements using phase contrast MRI in the first year of life. NMR Biomed. 25, 1063–1072 (2012).

Heiberg, E. et al. Design and validation of Segment - freely available software for cardiovascular image analysis. BMC Med. Imaging 10, 1 (2010).

Nagasawa, S., Kawanishi, M., Tada, Y., Kawabata, S. & Ohta, T. Intra-operative measurement of cortical arterial flow volumes in posterior circulation using Doppler sonography. Neurol. Res. 22, 194–6 (2000).

McLellan, S. A. & Walsh, T. S. Oxygen delivery and haemoglobin. Contin. Educ. Anaesthesia, Crit. Care Pain 4, 123–126 (2004).

Cole, T. J. Super Imposition by Translation and Rotation Growth Curve Analysis (R Package) (2017).

Cole, T. J., Freeman, J. V. & Preece, M. A. British 1990 growth reference centiles for weight, height, body mass index and head circumference fitted by maximum penalized likelihood. Stat. Med. 17, 407–429 (1998).

World Health Organisation. WHO Child Growth Standards (UK). Available at: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en/ (2006).

Ahrens, J., Geveci, B. & Law, C. ParaView: An End-User Tool for Large Data Visualization. (Elsevier, 2005).

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the families who supported this study. We thank staff from the St Thomas’ Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, including Dr Hammad Khan and Dr Geraint Lee; the Evelina London Children’s Hospital Fetal and Paediatric Cardiology Departments; the Evelina London Paediatric Intensive Care Unit; the Centre for the Developing Brain at King’s College London; our research radiologists Sophie Arulkumaran, Kelly Pegoretti, and Olivia Carney; our research radiographers, including Joanna Allsop, Ana Dos Santos Gomes and Elaine Green; and our neonatal research nurses including Julia Wurie and José Bueno Conde, whose energy and expertise made this study possible. This research was funded by the British Heart Foundation (FS/15/55/31649), the Medical Research Council UK (MR/K006355/1 and MR/L011530/1), European Research Council under the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007–2013)/European Research Council Grant Agreement no. 319456. The work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centres at Guys and St. Thomas NHS Trust.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.J.K. collected, analysed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. A.M. developed the automated segmentation and gyrification methods. L.C.-G. developed the motion correction methods and processed the structural images. J.H., A.P., M.M., R.P.A.G.T. and J.V.H. developed the neonatal-specific MRI sequences. E.H. supervised and conducted image acquisition. S.K. and L.R. analysed phase contrast data. J.K.S. provided clinical assistance during scanning. K.P. and J.S. provided clinical assistance and cardiology input. M.A.R. reviewed all images and interpreted results. H.Z., D.C.A., D.R., J.V.H. and A.D.E. assisted with data interpretation. S.J.C. supervised imaging, image processing, analysis and evaluation. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kelly, C.J., Makropoulos, A., Cordero-Grande, L. et al. Impaired development of the cerebral cortex in infants with congenital heart disease is correlated to reduced cerebral oxygen delivery. Sci Rep 7, 15088 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14939-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14939-z

This article is cited by

-

Single-cell analysis reveals the spatial-temporal expression of genes associated with esophageal malformations

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Effects of hemodynamic alterations and oxygen saturation on cerebral perfusion in congenital heart disease

Pediatric Research (2024)

-

Regional Cerebral Oxygen Saturation and Estimated Oxygen Extraction Ratio as Predictive Markers of Major Adverse Events in Infants with Congenital Heart Disease

Pediatric Cardiology (2023)

-

Ventricular and total brain volumes in infants with congenital heart disease: a longitudinal study

Journal of Perinatology (2020)

-

Investigating altered brain development in infants with congenital heart disease using tensor-based morphometry

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.