Abstract

It is critical to prepare smooth and dense perovskite films for the fabrication of high efficiency perovskite solar cells. However, solution casting process often results in films with pinhole formation and incomplete surface coverage. Herein, we demonstrate a fast and efficient vacuum deposition method to optimize the surface morphology of solution-based perovskite films. The obtained planar devices exhibit an average power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 13.42% with a standard deviation of ±2.15% and best efficiency of 15.57%. Furthermore, the devices also show excellent stability of over 30 days with a slight degradation <9% when stored under ambient conditions. We also investigated the effect of vacuum deposition thickness on the electron transportation and overall performance of the devices. This work provides a versatile approach to prepare high-quality perovskite films and paves a way for high-performance and stable perovskite photovoltaic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organometal halide perovskites (e.g., CH3NH3PbI3 (MAPbI3), CH3NH3PbCl3 (MAPbCl3)) have emerged as absorber materials for thin-film photovoltaic applications due to their desirable optoelectronic properties including high absorption coefficient, long exciton diffusion length, long carrier lifetime, high carrier mobility, tunable band gap and apparent tolerance of defects1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Recently, perovskite solar cells (PSCs) have been reported to achieve a certified efficiency of 22.1%, showing a potential to compete with traditional silicon photovoltaic industry in the near future8.

Compared with MAPbI3, MAPbIxCl3−x perovskite possess a higher charge carrier mobility and longer exciton diffusion length9,10, thus it is more attractive for fabrication of perovskite solar cells. Unfortunately, due to the specific characteristics of MAPbIxCl3−x perovskite, it is difficult to prepare smooth and dense perovskite films with fast and efficient method. Up to now, most of MAPbIxCl3−x perovskite layers were obtained by solution casting11,12,13. Totally, there are two types of solution casting methods: 1) one-step casting, the primary problem is that the film shrinkage would occur during the crystallization of perovskite due to the removal of solvent; 2) two-step casting, the main challenge is the volume expansion of PbI2 precursors because of the MAI intercalation. Thus, a few cracks or pinholes always appear in the perovskite films deposited by solution casting, leading to the deteriorated quality of the films and the resulting devices14,15,16,17,18. Vapor deposition technique is a promising alternative technique for preparing high-quality MAPbIxCl3−x perovskite films. Snaith et al. fabricated centimeter-scale MAPbIxCl3−x films with superior uniformity by a dual-source vapor deposition19. However, it is hard to control the precursor ratios precisely for obtaining high-quality perovskite films because of the complicated mechanism during the growth process. A layer-by-layer vapor-phase deposition approach was also developed to prepare high-quality MAPbIxCl3−x perovskite films to avoid the difficulty in controlling the precursor ratios20. The PSCs fabricated by this method showed an efficiency up to 14.29% while the film’s thickness can be precisely controlled by the deposition cycles. However, a long period was required in this method due to the limited reaction interfaces. Li et al. prepared MAPbIxCl3−x perovskite film using alternating precursor layer vacuum deposition and the device shows high performance and good stability. However, the relatively long period remains to be a major problems as described above21.

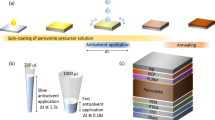

Herein, we developed a facile and effect method to overcome the shortcomings of the traditional methods as described above. In order to avoid the complicated process in traditional vapor deposition, we developed an optimized vacuum deposition solution hybrid method (VSHM) to fabricate perovskite thin films as showed in Fig. 1, in order to accelate the fabrication of perovskite films while remain a smooth surface and full coverage. The VSHM route mainly involves four steps: i) fabricating MAPbI3 perovskite film by solution casting on the TiO2/FTO glass (this process often results in films with pinhole formation and incomplete surface coverage); ii) forming the inorganic framework film by vacuum depositing PbCl2; iii) depositing the organic CH3NH3I by vacuum depositing on the PbCl2 films; iv) depositing hole transport material (HTM) and counter electrodes to form complete PSCs.

Results and Discussions

It is critical to control the thickness of PbCl2 layers for a complete transformation of PbCl2 into uniform MAPb(I, Cl)3 perovskite layer by reacting with CH3NH3I. Obviously, thick PbCl2 layers would cause an incomplete conversion of the compact PbCl2 films into MAPb(I, Cl)3 perovskite. In other words, a PbCl2 layer would be residual, which deteriorates the film quality and hampers the device performance. Figure 2 shows the SEM images of the MAPb(I, Cl)3 films optimized using VSHM, by depositing PbCl2 layers with the thickness of 20 nm, 40 nm, 60 nm and 80 nm, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2a, the surface presented many large pinholes between grain boundaries (the deposition thickness is 20 nm) and the pinholes gradually decreased with increasing the PbCl2 thickness. In Fig. 2b, the coverage of the films has been improved obviously, only a few pinholes still remain in the films with the size of about dozens of nanometer. When the PbCl2 thickness increased to 60 nm and 80 nm, the pinholes disappear completely with the full coverage of perovskite films. It is note worthy that there are some dots with sizes of tens of nanometers on the surface of 60 nm and 80 nm thickness PbCl2 layers. The tiny dots might be reactive “nuclei” for the growth of grains, originating from the reaction between PbCl2 and MAI vapor. With the presence of the newly formed perovskite crystals on the top, along with the “nuclei” decorated around, we believe that the intercalation reaction takes place on the top of the PbI2 films in this stage22.

Figure 3a shows the corresponding XRD patterns of MAPbI3 films on FTO/c-TiO2 substrate prepared by the solution-based method. A set of peaks at 14.08°, 28.41°, 31.85°, 41.25° and 43.19° could be assigned to the planes (110), (220), (310), (224) and (314) of the MAPbI3, respectively. Additionally, the XRD patterns of VSHM perovskite films are showed in Fig. 3b–e. The relative intensities of the MAPb(I, Cl)3 peaks are increased compared to the pristine films after optimizing by VSHM, indicating the improved the crystallinity of perovskites. Compared with the solution method, the enhanced (110) and (220) peaks in Fig. 3 for the as-deposited MAPb(I, Cl)3 perovskite coating indicates an increased orientation of crystalline domains by our VSHM. In short, the uniform MAPb(I, Cl) perovskite films with oriented crystalline domains ensure a high charge mobility necessary for high-performance solar cells23.

The Cl doping plays a key role in regulating the dynamics of exction/charge carrier transport in the MAPb(I, Cl)3 perovskite. Figure 4 shows a survey XPS spectrum for the MAPbI3 pristine perovskite and the MAPb(I, Cl)3 VSHM perovskite. As can be seen, the Cl element has been successful incorporated into the perovskite films via VSHM. In details, the Cl2p scan for the VSHM-based perovskite and pristine perovskite were shown in Fig. 4b,c. Apparently, the peaks located at 197.64 and 199.14 eV could be found in the scanning spectra of Cl2p.

The J-V curves of the VSHM solar cells are shown in Figure S1. The corresponding photovoltaic parameters were summarized in Table S1, including the short-current density (Jsc), the open-circuit voltage (Voc), the fill factor (FF) and the power conversion efficiency (PCE). There are 12 individual devices fabricating under different conditions. Compared to the pristine cells, the Jsc of 20 nm thick VSHM cells are improved evidently, from 17.46 to 19.88 mA cm−2. Result from the existence of cracks and pinholes in the pristine perovskite cells as shown in Fig. 2, which could be repaired by the PbCl2 vapor. When the thickness is increased from 20 to 40 nm, the Jsc and Voc get increased simultaneously, owing to the optimized quality of the perovskite films from either the reduced defects or the improved surface coverage. Both of them are benefited for hindering electron recombination and increasing the PCE to 12.50%. When the PbCl2 thickness is increased to 60 nm, it can be observed from Figure S1 that the Voc is increased a little bit, which is due to the 60nm-VSHM films have a full coverage than the above cells. The Jsc of the 60nm-VSHM cells are decreased obviously compared with 40nm-VSHM cells, leading to a PCE of 10.43%. This may be resulted from two reasons as following: Firstly, 60 nm thick PbCl2 films by vapor deposition are so dense that some PbCl2 are residue, which are harmful for electronic transport; secondly, when the thickness is up to 60 nm, there are lots of tiny dots on the surface of the perovskite films (Fig. 2c,d). It is speculated that these tiny dots are reactive PbCl2 nuclei which will increase the interface resistance between perovskite layer and HTM layer to hinder the electron transport. With the thickness of PbCl2 films increasing to 80 nm, the PCE of the devices further decreases to 9.13%. This illustrated that the films are too thick (>60 nm) for preparing perovskite absorbed layer, of which the reasons are similar to the 60nm-VSHM cells as described above. Although the PCE values of the cells optimized by VSHM are obviously improved than the pristine devices, it also can be further optimized by control the PbCl2 films by vapor deposition more accurately. It’s because that there are less number of pinholes in 20 and 40 nm-VSHM perovskite layers than those in the 60 nm-VSHM perovskites, owing to an incomplete transformation of PbCl2. According to the above, we speculate that the optimal PbCl2 thickness should be between 40 nm and 60 nm. Next, the optimal 50 nm-VSHM perovskite (called “VSHM perovskite” for abbreviation in latter section) films and subsequently PV devices will be discussed in detail.

Figure 5a,b shows the SEM image of pristine perovskite films with different magnification. It can be seen that lots of pinholes appeared between grains. In particular with Fig. 5b, we can see that the perovskite films exhibit poor coverage so that TiO2 porous layers are exposed. Figure 5c,d shows the SEM of perovskite films prepared by VSHM under the optimized conditions (50 nm). The pinholes nearly disappeared in perovskite films in Fig. 5c. From Fig. 5d, we can see the almost perfect perovskite which presents uniform morphology and density with a full coverage. The size of the perovskite grains are about 200–300 nm. In a word, the quality of perovskite films can be obviously improved by VSHM, due to the larger grains and the more full coverage.

Figure 6 shows the AFM images of pristine and VSHM perovskite films. The surface of pristine perovskite film is rough with an average roughness of about 45.6 nm. Compared to pristine perovskite films, the VSHM perovskite films are smoother with a smaller surface roughness of about 21.1 nm. This may be due to a smooth PbCl2 film as well as the repairing of the pinholes inside the perovskite films. Small surface roughness is benefited for depositing HTM layers and reducing the interface resistance to accelerate the charge transport24.

In order to investigate the electrical properties of the interfaces distinction between pristine and VSHM cells, the EIS measurement was performed in dark. As shown in Fig. 7, the Nyquist plot is usually composed of two irregular semicircles, including the small one at high frequency and the large one at low frequency, and the equivalent circuit is inserted in Fig. 7 25,26,27. The high frequency (corresponding to low Z’) intercept on the real axis (Z’ axis) represents the series resistance Rs, which is mainly associated to the resistance of FTO substrate28. Specifically, the semicircle in the high-frequency range results from the charge transfer resistance (R1) occurring at the perovskite/HTM interfaces, while the semicircle in the low-frequency range results from the charge recombination resistance (R2) at the TiO2/perovskite interface. From Fig. 7, the Rs and R1 of VSHM cells are nearly the same to that of the pristine cells, suggesting the series resistance is not increased by VSHM. The main difference lies in the R2 of perovskite devices. It could be observed that VSHM perovskite devices present a much higher resistance (R2) than the pristine one. The increased resistance implies a lower charge recombination at TiO2/perovskite interface. Because of the low carrier recombination rate at TiO2/perovskite interface, it is reasonable that VSHM cells show both higher Jsc and Voc than those of the pristine one.

As can be seen in Fig. 8, transient PL spectra are collected to further investigate the charge transport properties of the perovskite films derived from different deposition methods, including solution method (pristine cell) and VSHM method. Herein, the charge extraction capability of the MAPb(I, Cl)3 perovskite with VSHM is obviously superior to that of the pristine MAPbI3 film. The corresponding simulation curves of the cells fitted with a double exponential function are also shown in Fig. 8. From the fitted curves, the charge lifetime of the MAPb(I, Cl)3 perovskite fabricated via VSHM is estimated to be 20.7 ns, which is remarkably longer than the pristine cell (14.1 ns). Base on the previous reports, both the exctions diffusion length and the charge mobility have been reported to be significantly improved by the Cl doping9. On the other hand, the optimized surface morphology of VSHM films with full coverage is conducive to prevent charge recombination between perovskite films and charge transport layers.

The J-V curves of the PSCs with an optimized parameters are shown in Fig. 9, where a cross-sectional SEM image of the perovskite cell is inserted. The corresponding photovoltaic parameters were summarized in Table S2, including the short-current density (Jsc), the open-circuit voltage (Voc), the fill factor (FF) and the power conversion efficiency (PCE). The PCE of 50-nm VSHM cells are improved evidently to 15.57%, which is the highest PCE value in all of the VSHM cells. The reasons can be speculated as following: when the PbCl2 thickness is 50 nm, the perovskite layer is continuous without any pinholes, suggesting that 50 nm PbCl2 is thick enough to form a full coverage. Note that, unlike 60 nm or 80 nm VSHM perovskite, no “nuclei” appears in 50 nm VSHM perovskite, this will be helpful for the charge transportation.

PSCs are known to show an anomalous hysteresis in the J-V curves, making it difficult to characterize the device performance accurately. To ensure the accuracy of our characterization, the devices are investigated using different scanning directions as are shown in Fig. 9, in which no hysteresis is observed in the J-V curves. It suggests that the PCE measured from the J-V curves of our MAPb(I, Cl)3 perovskite solar cells are reliable. Such a hysteresis-free characteristic could be attributed to a low surface defect density of the perovskite films.

Moreover, our results indicate that high performance perovskite solar cells can be repeatedly fabricated using the VSHM route. Histograms of the Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE of 75 individual devices using the optimized layer thickness (50 nm) are given in Fig. 10, which show good reproducibility with a typical Voc value of 0.98 V, 19.80 mA cm−2 for Jsc, 0.70 for FF, and over 14% for PCE for more than 82% of the devices. In addition, the device fabricated by VSHM shows superior stability. Using a bare device without any encapsulation, we measured the J–V curves on a daily basis for 30 days under ambient conditions (humidity: ≤80%, temperature: ≤35 °C). Very good stability was demonstrated. Specifically, the PCE value remained over 90% of its initial efficiency after 30 days, as shown in Fig. 11. The parameters are listed in Table S3. We attribute such a remarkable stability to the full surface coverage of the dense perovskite films which facilitates preventing the moisture penetration.

In this study, we have developed VSHM, a facile and effective technique to fabricate perovskite films and the corresponding PV devices. The perovskite film derived from this approach exhibits smooth surface and full surface coverage. The obtained VSHM cells exhibited an average efficiency of the planar device is 13.42% with a standard deviation of ±2.15% and best efficiency as high as 15.57% and superior stability with the PCE value remained over 90% of its initial efficiency after 30 days. In a word, the VSHM has been demonstrated to be a versatile and controllable approach to the pursuit of high-quality perovskite films and the resulting high-performance, repeatable and stable PV devices.

Method

Synthesis of CH3NH3I

Methylammonium iodide (MAI) was synthesized by reacting methylamine (33 wt% in absolute ethanol, J&K) and hydroiodic acid (57 wt% in water with 1.5% hypophosphorous acid, J&K) at a 2: 1 molar ratio in ethanol in a 250 mL round bottom flask under nitrogen at 0 °C for 2 hours with stirring. After reaction, the white precipitate of MAI was recovered by rotary evaporation at 60 °C for 1 hour and then dissolved in ethanol. The pure MAI was recrystallized from ether and dried at 60 °C in a vacuum oven for 48 hours.

Device fabrication

Fluorine doped tin oxide glass substrates (FTO, Pilkington, TEC 15) were patterned by etching with Zn powder and 4 M HCl diluted in deionized water. The etched FTO substrates were subsequently cleaned by ultrasonication in a detergent solution, deionized water, acetone and isopropanol respectively, then rinsed with deionized water, ethanol and dried with clean dry air29,30,31,32. A dense blocking layer of TiO2 was deposited onto the substrate by spin-coating a TiO2 colloid solution at 3000 rpm for 30 seconds and then annealed at 450 °C for 1 hour. For the mesoporous TiO2 film, TiO2 paste (Dyesol, 18 NRT) was used in absolute ethanol in the ratio 1: 3.5 by weight, which was spin coated on the FTO/c-TiO2 substrates at 5000 rpm. for 30 seconds, followed by drying at 130 °C for 10 minutes sintering at 500 °C in air for 15 minutes. Two-step solution chemistry method was used to fabricate the underlayer CH3NH3PbI3 inside a glove box (Mikrouna, Universal). In briefly, PbI2 were dissolved in DMF (500 mg/mL) at 70 °C and spin-coated on the FTO/TiO2 substrates at 5000 rpm for 5 seconds then dried at 70 °C for 30 minutes. Upon cooling, CH3NH3I was dissolved in iso-propanol solution (10 mg/mL) at 70 °C dropped on FTO/TiO2/ PbI2 substrates for 120 seconds and spin-coated at 5000 rpm for 30 seconds. They were dried by spin-coating at 3000 rpm for 20 seconds and by heating at 70 °C for 30 minutes. For the VSHM samples, they were transferred into the evaporator which was inside the above glove box for PbCl2 and CH3NH3I evaporation. The thickness of the PbCl2 and CH3NH3I films were adjusted by the temperature and time of the evaporation. Full details of the evaporation are provided in the supporting information. Then, they were dried by heating at 70 °C for 30 minutes. The FTO/TiO2/Perovskite substrates were deposited by spin-coating a HTM layer solution at 3000 rpm for 30 seconds, where a spiro-OMeTAD (BoRun)/chlorobenzene (73.2 mg mL−1) solution was employed with addition of 17.5 µL Libis (trifluoromethanesulfonyl) imide (Li-TFSI, aladdin)/acetonitrile (520 mg mL−1) and 28.8 µL tert-butylpyridine (TBP, Sigma). Finally, the counter electrode was deposited by thermal evaporation of silver under a pressure of 8 × 10−5 Torr. The active area of the cell was measured to be 0.1 cm2 which was masked by a black tape during the testing of the cells.

Device characterization

X-ray diffraction spectra (XRD) were obtained from the perovskite samples deposited on the FTO/TiO2 substrates with a Bruker D8. Data were collected using a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer fitted with a Cu-Kα source operated at 40 kV and 30 mA, a 0.6 mm divergence slit, a 8 mm anti-scatter silt, a Ni filer for Cu-Kβ radiation, a 2.82° detector opening, a Primary soller slit secondary soller slit and a Lynxeye silicon strip detector. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) were also obtained from the perovskite samples deposited on the FTO/TiO2 substrates with ThermoEscalab 250 Xi (USA). The XPS source gun type with Al-Kα source and a 0.9 mm spot size. The surface morphology of samples were characterized by field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, Hitachi S-4800, Japan). Atomic force microscope (AFM) was performed using Bruker dimension icon scanning probe microscope (SPM) in “tapping” mode. UV–visible absorption spectra (UV-Vis-NIR, Shimadzu 3150, Japan) were used to study the optical properties perovskite. The photocurrent density–voltage (J–V) measurements were carried out under illumination of 100 mW cm−2 using a Keithley model 2420 digital source meter. A solar simulator was used to simulate sunlight by a 500 W xenon lamp light source fitted with an AM1.5 G filter (Newport Oriel Sol3A, 94023). The illumination intensity of 100 mW cm−2 was calibrated with a standard monocrystalline silicon solar cell which passed the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) calibration. The devices were measured between 0 V and 1.2 V under reverse or forward scan with the step voltage of 10 mV and the delay time 40 ms, respectively. The J–V curves for all devices were measured by masking the active area with a metal mask (0.1 cm2). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was conducted by using electrochemical test station (Zahner, IM6ex).

References

Kojima, A., Techima, K., Shirai, Y. & Miyasaka, T. Organometal Halide Perovskites as Visible-Light Sensitizers for Photovoltaic Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6050–6051 (2009).

Kim, S. et al. Relationship between ion migration and interfacial degradation of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite solar cells under thermal conditions. Sci. Rep. 7, 1200 (2017).

Burschka, J. et al. Sequential deposition as a route to high-performance perovskite-sensitized solar cells. Nature 499, 316–319 (2013).

Kim, H. S. et al. Lead Iodide Perovskite Sensitized All-Solid-State Submicron Thin Film Mesoscopic Solar Cell with Efficiency Exceeding 9%. Sci. Rep. 2, 591 (2012).

Chang, J. A. et al. High-performance nanostructured inorganic-organic heterojunction solar cells. Nano Lett. 10, 2609–2612 (2010).

Hodes, G. & Cahen, D. All-solid-state, semiconductor-sensitized nanoporous solar cells. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 705–713 (2012).

Jeon, N. J. et al. Compositional engineering of perovskite materials for high-performance solar cells. Nature 517, 476–480 (2015).

Stranks, S. D. et al. Electron-Hole Diffusion Lengths Exceeding 1 Micrometer in an Organometal Trihalide Perovskite Absorber. Science 342, 341–344 (2013).

Sudchanham, J. et al. Vortex Fluidics Improved Morphology of MAPbIxCl3−x Films for Perovskite Solar Cells. ChemistrySelect 2, 369–374 (2017).

Chen, Q. et al. Under the spotlight: The organic-inorganic hybrid halide perovskite for optoelectronic application. Nano Today 10, 355–396 (2015).

Jiang, C. Y. et al. Improvement of CH3NH3PbI3 Formation for Efficient and Better Reproducible Mesoscopic Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 24726–24732 (2015).

Eperon, G. E. et al. Morphological Control for High Performance, Solution-Processed Planar Heterojunction Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 151–157 (2014).

Azpiroz, J. M., Mosconi, E., Bisquert, J. & Angelis, F. D. Defect migration in methylammonium lead iodide and its role in perovskite solar cell operation. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 2118–2127 (2015).

Hwang, I., Jeong, I., Lee, J., Ko, M. J. & Yong, K. Enhancing Stability of Perovskite Solar Cells to Moisture by the Facile Hydrophobic Passivation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 17330–17336 (2015).

Niu, G. et al. Study on the stability of CH3NH3PbI3 films and the effect of post-modification by aluminum oxide in all-solid-state hybrid solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 705–710 (2014).

Kwon, Y. S., Lim, J., Yun, H.-J., Kim, Y.-H. & Park, T. A diketopyrrolopyrrole-containing hole transporting conjugated polymer for use in efficient stable organic–inorganic hybrid solar cells based on a perovskite. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 1454–1460 (2014).

Bai, Y. et al. Enhancing Stability and Efficiency of Perovskite Solar Cells with Crosslinkable Silane-Functionalized and Doped Fullerene. Nature Comm. 7, 12806 (2016).

Liu, M. Z., Johnston, M. B. & Snaith, H. J. Efficient planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells by vapour deposition. Nature 501, 395–398 (2013).

Chen, Y. H., Chen, T. & Dai, L. M. Layer-by-Layer Growth of CH3NH3PbI3−xClx for Highly Efficient Planar Heterojunction Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 27, 1053–1059 (2015).

Yang, D. et al. Alternating precursor layer deposition for highly stable perovskite films towards efficient solar cells using vacuum deposition. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3, 9401–9405 (2015).

Chen, Q. et al. Planar Heterojunction Perovskite Solar Cells Via Vapor-Asssisted Solution Process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 622–625 (2014).

Etgar, L. et al. Mesoscopic CH3NH3PbI3/TiO2 Heterojunction Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17396–17399 (2012).

Carrillo, J. et al. Ionic reactivity at Contacts and Aging of Methylammonium Lead Triiodide Perovskite SolarCell. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1502246 (2016).

Zhu, L. et al. Double junction photoelectrochemical solar cells based on Cu2ZnSnS4/Cu2ZnSnSe4 thin film as composite photocathode. Appl. Surf. Sci. 292, 55–62 (2014).

Li, X. et al. Outdoor Performance and Stability under Elevated Temperatures and Long-Term Light Soaking of Triple-Layer Mesoporous Perovskite Photovoltaics. Energy Technol 3, 551–555 (2015).

Zhao, B. G. et al. Improved performance of perovskite solar cell by controlling CH3NH3PbI3−xClx film morphology with CH3NH3Cl-assisted method. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 27, 10869–10876 (2016).

Wang, K. et al. Low-Temperature and Solution-Processed Amorphous WOx as Electron-Selective Layer for Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 755–759 (2015).

Hawash, Z., Ono, L. K., Raga, S. R., Lee, M. V. & Qi, Y. Air-Exposure Induced Dopant Redistribution and Energy Level Shifts in Spin-Coated Spiro-OMeTAD Films. Chem. Mater. 27, 562–569 (2015).

Liu, F. et al. Perovskite Solar Cells: Is Excess PbI2 Beneficial for Perovskite Solar Cell Performance? Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1502206 (2016).

Shao, Y. et al. Grain Boundary Dominated Ion Migration in Polycrystalline Organic-Inorganic Halide Perovskite Films. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 1752–1759 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. A dopant-free organic hole transport material for efficient planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 11940–11947 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2015QNA09).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jinfeng Wang contributed to the overall project and wrote an entire manuscript. Benguang Zhao, Zheng Xing and Lei Zhu performed the data analysis, fabricated the perovskite solar cell and characterized the J-V performances. Lei Zhu, Xiuquan Gu and Jian Song discussed the results and commented on the manuscript, Yulong Zhao and Yinghuai Qiang designed and supervised this project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, JF., Zhu, L., Zhao, BG. et al. Surface engineering of perovskite films for efficient solar cells. Sci Rep 7, 14478 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14920-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14920-w

This article is cited by

-

Composition-Driven Structural, Optical, Thermal and Electrochemical Properties of Hybrid Perovskite-Structured Methylammonium-Tin-Chloride

Journal of Electronic Materials (2024)

-

Perovskite Solar Cells Based on Compact, Smooth FA0.1MA0.9PbI3 Film with Efficiency Exceeding 22%

Nanoscale Research Letters (2020)

-

Butanol-assisted solvent annealing of CH3NH3PbI3 film for high-efficient perovskite solar cells

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2019)

-

Improved performance and reproducibility of perovskite solar cells by jointly tuning the hole transport layer and the perovskite layer deposition

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.