Abstract

Hybridization with invasive species is one of the major threats to the phenotypic and genetic persistence of native organisms worldwide. Arion vulgaris (syn. lusitanicus) is a major agricultural pest slug that successfully invaded many European countries in recent decades, but its impact on closely related native species remains unclear. Here, we hypothesized that the regional decline of native A. rufus is connected with the spread of invasive A. vulgaris, and tested whether this can be linked to hybridization between the two species by analyzing 625 Arion sp. along altitudinal transects in three regions in Switzerland. In each region, we observed clear evidence of different degrees of genetic admixture, suggesting recurrent hybridization beyond the first generation. We found spatial differences in admixture patterns that might reflect distinct invasion histories among the regions. Our analyses provide a landscape level perspective for the genetic interactions between invasive and native animals during the invasion. We predict that without specific management action, A. vulgaris will further expand its range, which might lead to local extinction of A. rufus and other native slugs in the near future. Similar processes are likely occurring in other regions currently invaded by A. vulgaris.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The displacement of native species by invasive ones is a serious threat to biodiversity worldwide, and is becoming more frequent due to the increasing number of species introductions1,2. Among the mechanisms of such displacement are very often competition or predation3,4. However, invasive species can also displace native organisms genetically, through hybridization and introgression5,6. This mixing of gene pools and potential loss of genotypically distinct species is especially problematic for rare organisms coming into contact with more abundant ones7,8.

Hybridization might have different outcomes for the native and invasive species. Even though hybridization can in some cases contribute to generating species diversity9, the hybrid offspring could also be infertile or have reduced fitness, which may lead to decline and even extinction of the native species’ populations10,11. Moreover, hybridization can result in speciation reversal, and change the functional roles of organisms in the ecosystem12,13. For the invasive species, hybridization may provide advantages by increasing their invasiveness or adaptive potential to local environments14,15,16. The consequences of hybridization can be particularly challenging for conservation biology, because it is difficult to develop management strategies for hybrids of endangered species17. Therefore, to be able to protect native organisms and prevent spread of invaders, it is crucial to understand whether hybridization has occurred as well as what are its likely impacts.

Most studies on the impacts of hybridization between invasive and native species have been conducted in plants (e.g. ref.4,5), with only a few in animals (e.g. ref.15,18). Among the major animal taxonomic groups, molluscs have the highest number of documented extinctions, which has been attributed in part to interactions with other mollusc species invading native species ranges19. However, the role of hybridization with invasive species in molluscs remains poorly understood.

The hermaphroditic slug Arion vulgaris Moquin-Tandon 1855 (also referred to as non-topotype A. lusitanicus Mabille 1868) is considered one of the 100 most invasive species in Europe20, being a serious pest both in agriculture and gardening21,22. It has spread and become established in many European countries since the 1950’s23,24,25, but see ref.26 and represents an excellent case for studying the genetic impacts on native species, such as A. rufus (Linnaeus 1758). This closely related native slug used to be abundant in forests and meadows27, but recently has been listed as “vulnerable” on the Red List of endangered species in several European countries28,29. It has been reported that when A. vulgaris enters an area, the populations of A. rufus begin to decline, and hybridization is suspected to be one of the underlying mechanisms30,31.

The possibility and extent of hybridization among the three large Arion species – A. vulgaris, A. rufus, and A. ater (Linnaeus 1758) – has been sparked by and questioned following the observation of intermediate morphological phenotypes in the field and mating experiments under experimental laboratory conditions32,33. Initial genetic investigations indicated hybridization between the invasive A. vulgaris and native A. ater or A. rufus in particular34,35,36, but low-resolution genetic markers and sample sizes limited the conclusiveness. Thus, it remains unanswered how frequently hybridization among the invasive A. vulgaris and the native A. rufus occurs, and whether hybrid offspring can persist and have a lasting impact on natural populations.

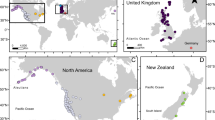

In order to characterize the interactions between invasive A. vulgaris and native A. rufus, we examined the zone of contact of these two species in three different locations. In Switzerland, A. vulgaris has established a continuous distribution below 1000 m above sea level (a.s.l.) according to morphological assessment28 and given its synanthropic nature this species is often present in cities and villages28,37. However, species identification based on external morphology may be misleading36 and genetic analyses of the slug invasion are lacking in Switzerland and elsewhere. Nonetheless, the most abundant large Arion slugs in cultivated areas in the Swiss lowlands are most likely A. vulgaris, while the native A. rufus is nowadays thought to be limited to higher altitudes28. In order to determine if and where in the landscape the two species are in contact, we sampled slugs along altitudinal transects ranging from urbanized areas in valleys to relatively pristine habitats on mountain tops (Fig. 1). Given that the first occurrence record of A. vulgaris in Switzerland dates back to 195538, the potential interactions between the invading and native species may have occurred over about 60 generations in the region, and our investigation could thus provide valuable insights into the genetic impacts of a recent invasion process. Specifically, in this study we assessed i) whether there is evidence of past or recent hybridization between the two species, and ii) whether there is consistency between genetic and morphological species assignment, with the potential implications for management of the invasive and conservation of the native species.

Genetic admixture between Arion vulgaris and A. rufus along the altitudinal transects Blumenstein (B), Salvan (S) and Filfalle (F) in Switzerland. Pie charts represent average assignment probabilities from STRUCTURE for the two species based on nuclear DNA. The genetic cluster representing A. vulgaris is shown in red, A. rufus in blue. Individual membership coefficients are displayed in the bar plots: each individual is represented by a single horizontal bar, with sampling location labels shown on the right. Sampling locations are separated by a black line. The patterns suggest the presence of a zone of genetic admixture at intermediate altitudes for S and B. The Filfalle transect shows signs of more extensive admixture between the invasive and the native Arion species. This figure was produced using the ArcGIS software version 10.2.2 (www.esri.com/software/Arcgis).

Results

Species identification based on mtDNA and morphology

Phylogenetic reconstructions clearly distinguished two clades representing the invasive and native species (Fig. S3). Forty-five individuals carried A. rufus and 60 A. vulgaris mtDNA haplotypes, with extensive sharing of haplotypes between the three altitudinal transects. Our sequencing yielded two different haplotypes for A. vulgaris and three haplotypes for A. rufus, and these differed in at least 60 nucleotides between the species (Fig. 2). Mitochondrial DNA from both species was detected in pasture and forested habitats but there was strong variation between transects and altitude (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

Statistical parsimony haplotype network of the 105 ND1 sequences of A. vulgaris (left) and A. rufus (right) sampled in the Blumenstein, Filfalle and Salvan transects. Each circle represents one unique haplotype, and its size is proportional to the number of individuals with the particular haplotype. Number of individuals with the same haplotype is indicated above the circles. Mutations are shown as hatch marks. Number of individuals and sampling locations are listed in Tables 1–3.

Based on internal morphology we were able to classify 89 out of the 105 individuals sequenced for mtDNA. The remaining 16 specimens had immature genitalia or their preservation state did not permit a clear identification. Genital morphology allowed us to identify 59 individuals as A. vulgaris, 23 as A. rufus, whereas the remaining seven showed intermediate morphological characteristics (Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4).

Signs of admixture and frequency of hybrids

All microsatellite loci were highly polymorphic with an average of 15 alleles per locus (ranging from 9 to 26, Table S1). Using the threshold values obtained in HYBRIDLAB, we detected the presence of both non-admixed and admixed individuals in each transect with large differences regarding the frequency and distribution of hybrids. Out of the 183 individuals analysed in the Blumenstein transect, 49 were identified as non-admixed A. vulgaris, 54 as non-admixed A. rufus and 80 as hybrids with various levels of admixture. In the Salvan transect, 66 individuals were identified as pure A. vulgaris, 99 as pure A. rufus and 36 as hybrids. In the Filfalle transect, there were 25 and 31 pure A. vulgaris and pure A. rufus, respectively, and 185 individuals identified as hybrids. Overall, we detected five cases (1–2 per transect) of mitonuclear discordance in both directions, i.e. species assignment for these individuals based on the autosomal loci was different from mtDNA (Table 4, Fig. S4). Genetic differentiation between non-admixed A. vulgaris and A. rufus in the three study regions was significant (p < 0.001) and relatively high in Blumenstein (FST = 0.425) and Salvan (FST = 0.475) but lower in Filfalle (FST = 0.186).

Spatial patterns in nuclear DNA

The PCoA separated most non-admixed A. vulgaris in the Salvan transect clearly from non-admixed A. rufus (defined by the thresholds identified in HYBRIDLAB) with likely hybrids in between (Fig. 3). The first and second axis accounted for 26% and 4% of the variation, respectively. The separation between the species was less pronounced in the Blumenstein transect and practically non-existent in the Filfalle transect (Fig. S5).

Results of the principal coordinate analysis for Arion sp. in the Salvan transect based on microsatellite genotypes. Individuals are colour-coded based on the HYBRIDLAB results: red – pure A. vulgaris (q-value < 0.05), blue – pure A. rufus (q-value > 0.95), yellow – admixed individuals (q-value 0.06–0.94). The percentage of the total variation in the dataset explained by each principal coordinate is given in parentheses. See Fig. S3 for the Blumenstein and Filfalle transects.

Combining the three transect datasets for the Bayesian analysis, there was extensive structure among and within transects with gradual transitions between genotype clusters in each study region (Fig. S6). The Evanno approach suggested that the most likely number of genetic clusters was K = 2 for Blumenstein and Salvan, reflecting the results of mtDNA analysis regarding the general distribution of the two species and the PCoA. The genetic cluster representing A. vulgaris was present in the lowest parts of the sampling transects and A. rufus in the highest parts with different levels of admixture at approximately intermediate altitudes (Fig. 1). For the Filfalle transect, the Evanno approach suggested K = 8 as the most likely number of clusters. However, given the presence of mtDNA from two species only, we used K = 2 for further analyses of the Filfalle dataset. This showed that a majority of A. vulgaris genotypes were found at low altitudes. Despite different levels of admixture in the three study regions, all results were consistent among independent STRUCTURE runs.

When we estimated the position of the contact between species along the altitudinal transects with hzar, all fitted clines converged to the same values showing a single likelihood peak each. We observed relatively steep genetic clines of species transition with significant differences among the transects (Fig. 4). The cline centres were estimated to be located at 1,569 m a.s.l. in Blumenstein, 1,404 m a.s.l. in Salvan and at 1,186 m a.s.l. in Filfalle (Table S2). In addition to having the cline centre at the lowest altitude, Filfalle also displayed a very low estimated cline width (13 m of elevational difference) in comparison to Blumenstein (320 m) and Salvan (185 m; Table S2).

Results of the cline analyses for the three altitudinal transects (B – Blumenstein, S – Salvan, F – Filfalle) based on the average q-value for each sampling location obtained with STRUCTURE. Elevation in metres above sea level is on the x-axis and the probability of belonging to the A. rufus cluster (q-value) on the y-axis. Circles correspond to sampling locations and their size is proportional to the number of samples within a cline. The 95% credible cline region is indicated in grey. Filfalle shows signs of more extensive admixture between the invasive and the native Arion species also at the highest altitudes. The altitude of the centre of the cline is indicated by a dashed line.

Discussion

In this study, we provided a landscape level perspective on the spatial genetic consequences of the early stages of contact between an invasive and native animal species. Genetically confirmed A. vulgaris was predominantly found in disturbed areas around settlements and A. rufus in more natural habitats at higher altitude which is consistent with a human contribution e.g. through inadvertent introduction at the origin of the invasion process. Considering the overlapping external morphology between the two species, we propose molecular techniques be used as the primary method of species identification for these taxa.

Our analyses provided the first large-scale evidence of hybridization between the invasive A. vulgaris and native A. rufus under natural conditions. This supports previous suggestions that hybridization is possible (e.g. ref.32,34), despite the divergence time among extant Arion spp. slugs estimated at approximately 5 Mya39. More importantly, this study shows that hybridization can be common where the two species co-occur, and through our design of small-scale landscape level transects in comparison with other studies spanning tens or hundreds of km (e.g. ref.40,41) we were able to precisely determine the position of the A. vulgaris invasion front.

The detection of individuals with different levels of admixture in all three regions suggests that interspecific mating is not limited to the first generation of hybrids. This is corroborated by the observation of a few individuals displaying mitonuclear discordance in both directions which requires several successful reproduction events of hybrids and backcrosses over multiple generations (Table 4; Fig. S4; ref.42,43).

Evidence of hybridization was observed in all three study regions but genetic admixture seems to be particularly extensive in the Filfalle transect. This could be explained by at least two scenarios. First, the two species have been in contact for more time than in the other transects. It is unknown when exactly the two species came into contact in the respective regions but the shared mtDNA haplotypes between regions (Fig. 2) – that are also frequent in the invaded ranges elsewhere in Europe25 – provide no indication of a substantially different local invasion history in Filfalle. Second, it is possible that the A. vulgaris slugs that invaded this region were already admixed which would explain the overall lower level of differentiation in nuclear DNA between the taxa in this region. A third possibility would be two consecutive invasions of the region. The first invasion could have led to extensive admixture even at high altitudes while the second one with mostly pure A. vulgaris is still ongoing. Very specific demographic analyses might be able to differentiate between these invasion scenarios but this would require vast genomic data sets44.

Theoretical work by Currat et al.7 predicts that in the zone of contact, invaders could have experienced more introgression at selectively-neutral genes than the native species. These predictions have been supported in several empirical studies (e.g. ref.8,45,46), which however investigated hybrid zones that have existed for a long time. In our system, the invasion of A. vulgaris in Switzerland started approximately 60 years ago38, and we did not detect a pattern of asymmetrical introgression. It is unclear if this will build up over time and potentially lead to larger geographic regions with introgressed individuals (e.g. ref.42,47). Accordingly, very little pronounced patterns are expected in this regards for the regions of Europe that were more recently invaded or are currently being invaded by A. vulgaris 25.

Because our study represents to our knowledge the first genetic assessment of the levels of introgression in Arion sp. slugs at the landscape scale, we do not have a baseline from an earlier time point to which these levels could be compared. We thus cannot determine with certainty whether the trend of introgression is declining or increasing. However, several studies have suggested that the propensity to hybridize might be influenced by relative abundance48,49, and if the more abundant A. vulgaris continues to spread, we predict that it will eventually lead to introgressive replacement of A. rufus. Such genetic replacement has been described for example in native newts8, crayfish50 and mussels51.

Nevertheless, additional factors could be contributing to the disappearance of A. rufus. Invasive species are often considered competitively dominant: they might use food resources more rapidly and/or efficiently than native species52, exhibit rapid adaptation and spread53, faster growth rates54 and higher reproductive output55. Indeed, A. vulgaris seems to be able to use food resources more efficiently than native species56,57, and shows a more pronounced exploratory behaviour in novel environments58,59. Further, A. vulgaris seems to be able to cope with land use change and agricultural intensification better than the native species60. Together with hybridization, these factors might cause local extinction of A. rufus in the near future.

The two species mostly occurred in different habitats, as described by Rüetschi et al.28 based on morphological assessments. The contact between A. rufus and A. vulgaris is currently at intermediate altitudes (Fig. 1) with the cline centres at different elevations in each region (Fig. 4, Table S2), which might indicate differences in local invasion histories of A. vulgaris 61,62 as mentioned above. While the analogous highest altitude of slug occurrence in all study regions suggests environmental factors (e.g. temperature) constraining further spread of both species57, it would be interesting to implement long-term genetic monitoring to document any further expansion of A. vulgaris over time62.

Most of the individuals assigned by nucDNA as hybrids were morphologically identified as either species (Table 4). Species identification of Arion taxa is notoriously difficult especially regarding differentiation based on external morphology36, and hybridization adds another complication. Although morphological species assignment is still extensively used for Arion spp. slugs (e.g. ref.63,64), our results stress that identification should be primarily based on molecular techniques, particularly in regions where multiple species co-occur. In order to preserve the native, often endangered species, we encourage the use of non-invasive DNA sampling methods (e.g. ref.65,66) whenever possible.

Some of the observed discrepancy between genetic and internal morphological species assignment (Table 4) might be caused by phenotypic overlap, i.e. hybrids after the F1 generation could be difficult to tell apart from parental species17,67. In this case, the removal of morphologically indistinguishable hybrids from mixed populations would be impossible, and management efforts need to focus primarily on prevention of further spread in the landscape and new introductions of the invasive slug.

We have unequivocally established that A. vulgaris – one of the most destructive agricultural pest slugs in Europe – is able to hybridize with A. rufus and produce fertile offspring in the natural environment. Given the current rapid spread of A. vulgaris through vast areas of Europe, similar processes might be acting in other countries and closely related species although the time in contact is shorter in most regions and there is no evidence of “de-speciation” at larger scales yet25. Nevertheless, the invasion of the slug A. vulgaris may constitute a larger threat to native Arion species than previously considered.

Materials and Methods

Field sampling and morphological species identification

We chose three study regions (Blumenstein, Salvan and Filfalle) in the Swiss Prealps based on the occurrence records of A. rufus in the last 10 years38 (Fig. 1). In each study region, sampling along an elevational transect started in a settlement area and continued through mostly forested locations and pastures to higher altitudes (Fig. 1; Tables 1, 2 and 3). As the home range size of A. vulgaris has been estimated to be approximately 45 m2 68, sampling locations within a transect were spaced at least 50 meters apart to increase the chance of capturing unrelated individuals. Along the transect Blumenstein, 183 individuals were sampled from 21 locations in the altitudinal range of 664–1,872 m a.s.l. (Table 1). The transect Salvan comprised 16 locations, yielding 201 individuals from altitudes between 1,123 and 1,845 m a.s.l. (Table 2), and in the transect Filfalle, we collected 241 individuals from 22 locations (altitude 1,173–1,801 m a.s.l.; Table 3). The highest altitudes in the transects constituted the upper limit of where we detected Arion slugs in the respective locations. In total, 625 slugs were analysed.

Slugs were collected directly in the field during rainy weather or at night, or by placing a trap designed by the authors (described in detail in Fig. S1) overnight. Slugs were killed by freezing at -20 °C for at least eight hours and the whole specimens were preserved in absolute ethanol. Slugs that were analysed with both mitochondrial and nuclear markers (105 individuals) were dissected and classified as either A. vulgaris, A. rufus or an intermediate form based on internal morphological traits of reproductive organs37,69. DNA was extracted from a small piece of foot tissue using proteinase K and the high-salt extraction method70. After dilution in double-distilled water, the DNA was stored at −20 °C.

Mitochondrial DNA analyses

In order to confirm that both A. vulgaris and A. rufus were present in each region, we sequenced the mtDNA gene ND1 in 32–38 Arion sp. individuals per transect (Tables 1, 2 and 3), totalling 105 slugs. Locus specific primers MOL-NAD1F (5′-CGRAARGGMCCTAACAARGTTGG-3′) and MOL-NAD1R (5′-GGRGCACGATTWGTCTCNGCTA-3′) developed by Quinteiro et al.39 were used to amplify a 350 bp long fragment, following the protocol described in Zemanova et al.25. The sequencing reactions were visualized on an ABI Prism 3130 (Applied Biosystems).

To assign slug mtDNA to the native or invasive species, we aligned our novel ND1 sequences with reference sequences from our previous study25 covering the entire distribution range of the species: A. vulgaris sequences with the accession numbers KX834566, KX834594, KX834637 and A. rufus sequences with the accession numbers KX834609, KX834617, KX834665. We also used one A. subfuscus Draparnaud 1805 sequence (accession number AY316248) as outgroup for the phylogenetic analysis. DNA sequences were aligned in BIOEDIT 7.1.371 and the number of haplotypes was determined in DNASP 572. The phylogenetic tree was produced following the methodology described in Zemanova et al.25. In order to visualize relationships between haplotypes in either of the two species, we reconstructed a statistical parsimony haplotype network in POPART 173.

Nuclear DNA analyses

Genotyping with microsatellite markers

We genotyped all 625 Arion sp. individuals with fifteen nuclear microsatellite markers (nucDNA) ALU_02_3, ALU_06_4, ALU_11_2, ALU_12_2, ALU_13_2, ALU_30_2, ALU_34_2, ALU_37_2, ALU_60_2, ALU_76_2, ALU_79_2, ALU_86_2, ALU_88_2, ALU_92_2 and ALU_96_274 in three primer mixes. The 10 µl PCRs contained approximately 100 ng DNA, 1 µl of primer mix, 5 µl of Qiagen multiplex kit and 3 µl of H2O. The PCR temperature profile was as follows: 15 min initial denaturation at 96 °C, followed by 32 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 sec, annealing at 57 °C for 1 min 30 sec, extension at 72 °C for 1 min 30 sec, and the final extension step of 30 min at 60 °C. The PCR product was diluted with 20 μl of distilled H2O and 1.2 μl of the diluted product were mixed with 12 μl of the internal size standard (GeneScan 500 LIZ, Applied Biosystems) to determine the size of alleles. The amplified fragments were separated on an ABI Prism 3130 Genetic Analyzer and fragment lengths were scored in GENEMAPPER 3.7 (Applied Biosystems). Approximately 10% of the samples were re-amplified and genotyped independently to ensure genotyping consistency.

Genetic diversity and estimates of admixture

The number of alleles per locus was calculated in GENALEX 6.575. We also conducted a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) in the same software to summarize major patterns of variation in the microsatellite genotype dataset. FSTAT 2.9.3.276 was used to measure the average pair-wise level of genetic differentiation (FST) between 50 individuals in each transect classified by the Bayesian analysis (see below) as either non-admixed A. vulgaris or A. rufus. We used Bayesian assignment implemented in STRUCTURE 2.3.477 to identify genetic clusters in the Arion sp. samples. Analyses were run using the admixture model with correlated allele frequencies and without sampling location priors, with a burn-in period of 100,000 iterations followed by 1,000,000 MCMC iterations. The number of clusters (K) was set to range from 1 to 10, with 10 replicates for each K value. The optimal number of clusters was estimated using the Evanno approach78 implemented in Structure Harvester 0.6.9479. These analyses were run separately for each transect, as well as for all three transects together.

To identify the optimal threshold q-value (i.e. the probability of belonging to a genetic cluster) for distinguishing between non-admixed individuals and potential hybrids between the two species, we used Hybridlab 1.080 to simulate parental and hybrid genotypes in each transect. The parental genotypes used for the simulations consisted of 50 individuals assigned to their genetic cluster with a q-value above 0.8. We simulated 10 data sets each with 100 generated genotypes of each parental and hybrid class (F1, F2, backcross with A. vulgaris, backcross with A. rufus). The simulated data sets were evaluated in STRUCTURE with K = 2 and 50,000 MCMC iterations following a burn-in period of 10,000. The accuracy and efficiency of assignment of the generated genotypes was calculated using the thresholds of 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3, following the procedure described in Vähä & Primmer81. The HYBRIDLAB results suggested that the best thresholds for delimiting non-admixed and hybrid individuals were 0.05 for Blumenstein and Salvan, and 0.15 for Filfalle (Fig. S2).

Cline analyses

To estimate the location and the spatial extent of admixture along the altitudinal transects, we conducted cline analyses with averaged q-values per sampling location using the statistical package hzar 82 implemented in R 3.1.183. We modeled the cline shape using three equations84,85,86 that describe a sigmoid shape at the centre of the transition with two exponential decay curves on either side of the transition. We estimated the centre and width of each cline, and fitted three sets of three cline models using the Metropolis-Hasting algorithm. Model one had no scaling, model two had fixed scaling, and model three allowed the Pmin and Pmax (i.e. the bottom and top of a cline) to vary. We compared these models to a null model of no clinal transition. We ran each model for 100,000 iterations and assessed convergence and stability by visualizing the MCMC traces. We then selected the best-fit model based on the comparison of corrected AIC values.

Data accessibility

DNA sequences are available in GENBANK under accession numbers MG253687-MG253791. Genotype data are available in Dryad under doi:10.5061/dryad.rb187.

References

Davis, M. A. Invasion Biology. (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Lowry, E. et al. Biological invasions: a field synopsis, systematic review, and database of the literature. Ecology and Evolution 3, 182–196 (2013).

Luque, G. M. et al. The 100th of the world’s worst invasive alien species. Biological Invasions 16, 981–985 (2014).

Mooney, H. A. & Cleland, E. E. The evolutionary impact of invasive species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98, 5446–5451 (2001).

Ayres, D. R., Smith, D. L., Zaremba, K., Klohr, S. & Strong, D. R. Spread of exotic cordgrasses and hybrids (Spartina sp.) in the tidal marshes of San Francisco Bay, California, USA. Biological Invasions 6, 221–231 (2004).

Kovach, R. P. et al. Dispersal and selection mediate hybridization between a native and invasive species. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 282, 20142454 (2015).

Currat, M., Ruedi, M., Petit, R. J. & Excoffier, L. The hidden side of invasions: massive introgression by local genes. Evolution 62, 1908–1920 (2008).

Dufresnes, C. et al. Massive genetic introgression in threatened northern crested newts (Triturus cristatus) by an invasive congener (T. carnifex) in Western Switzerland. Conservation Genetics 17, 839–846 (2016).

Abbott, R. et al. Hybridization and speciation. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 26, 229–246 (2013).

Hegde, S. G., Nason, J. D., Clegg, J. M., Ellstrand, N. C. & Soltis, P. The evolution of California’s wild radish has resulted in the extinction of its progenitors. Evolution 60, 1187–1197 (2006).

Leary, R. F., Allendorf, F. W. & Forbes, S. H. Conservation genetics of bull trout in the Columbia and Klamath river drainages. Conservation Biology 7, 856–865 (1993).

Seehausen, O. Conservation: losing biodiversity by reverse speciation. Current Biology 16, R334–R337 (2006).

Vonlanthen, P. et al. Eutrophication causes speciation reversal in whitefish adaptive radiations. Nature 482, 357–362 (2012).

Abbott, R. J., Ashton, P. A. & Forbes, D. G. Introgressive origin of the radiate groundsel, Senecio vulgaris L. var. hibernicus Syme: AAT-3 evidence. Heredity 68, 425–435 (1992).

Facon, B., Jarne, P., Pointier, J. P. & David, P. Hybridization and invasiveness in the freshwater snail Melanoides tuberculata: hybrid vigour is more important than increase in genetic variance. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 18, 524–535 (2005).

Ridley, C. E. & Ellstrand, N. C. Evolution of enhanced reproduction in the hybrid-derived invasive, California wild radish (Raphanus sativus). Biological Invasions 11, 2251–2264 (2009).

Sakai, A. K. et al. The population biology of invasive species. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 32, 305–332 (2001).

Blum, M. J., Walters, D. M., Burkhead, N. M., Freeman, B. J. & Porter, B. A. Reproductive isolation and the expansion of an invasive hybrid swarm. Biological Invasions 12, 2825–2836 (2010).

Lydeard, C. et al. The global decline of nonmarine mollusks. BioScience 54, 321–330 (2004).

DAISIE. Handbook of alien species in Europe (Springer, 2009).

Briner, T. & Frank, T. The palatability of 78 wildflower strip plants to the slug Arion lusitanicus. Annals of Applied Biology 133, 123–133 (1998).

Kozlowski, J. The distribution, biology, population dynamics and harmfulness of Arion lusitanicus Mabille, 1868 (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Arionidae) in Poland. Journal of Plant Protection Research 47, 219–230 (2007).

Engelke, S., Koempf, J., Jordaens, K., Tomiuk, J. & Parker, E. D. The genetic dynamics of the rapid and recent colonization of Denmark by Arion lusitanicus (Mollusca, Pulmonata, Arionidae). Genetica 139, 709–721 (2011).

Rabitsch, W. Arion vulgaris (Moquin-Tandon, 1855) fact sheet. Online database of delivering alien invasive species inventories for Europe, http://www.europe-aliens.org/pdf/Arion_vulgaris.pdf (2006).

Zemanova, M. A., Knop, E. & Heckel, G. Phylogeographic past and invasive presence of Arion pest slugs in Europe. Molecular Ecology 25, 5747–5764 (2016).

Pfenninger, M., Weigand, A., Balint, M. & Klussmann-Kolb, A. Misperceived invasion: the Lusitanian slug (Arion lusitanicus auct. non-Mabille or Arion vulgaris Moquin-Tandon 1855) is native to CentralEurope. Evolutionary Applications 7, 702–713 (2014).

Janus, H. Unsere Schnecken und Muscheln. 3. edn, 124 (Franckh, 1968).

Rüetschi, J., Stucki, P., Müller, P., Vicentini, H. & Claude, F. Rote Liste Weichtiere (Schnecken und Muscheln). Gefährdete Arten der Schweiz, Stand 2010. (Bundesamt für Umwelt und Schweizer Zentrum für die Kartografie der Fauna, 2012).

Welter-Schultes, F. W. European non-marine molluscs, a guide for species identification. (Planet Poster Editions, 2012).

Davies, S. M. Arion flagellus Collinge and Arion lusitanicus Mabille in the British Isles: a morphological, biological and taxonomic investigation. Journal of Conchology 32, 339–354 (1987).

von Proschwitz, T. Arion lusitanicus Mabille and A. rufus (L.) in Sweden: a comparison of occurrence, spread and naturalization of two alien slug species. Heldia 4, 137–138 (1997).

Dreijers, E., Reise, H. & Hutchinson, J. M. C. Mating of the slugs Arion lusitanicus auct. non Mabille and A. rufus (L.): different genitalia and mating behaviours are incomplete barriers to interspecific sperm exchange. Journal of Molluscan Studies 79, 51–63 (2013).

Roth, S., Hatteland, B. A. & Solhoy, T. Some notes on reproductive biology and mating behaviour of Arion vulgaris Moquin-Tandon 1855 in Norway including a mating experiment with a hybrid of Arion rufus (Linnaeus 1785) x ater (Linnaeus 1758). Journal of Conchology 41, 249–257 (2012).

Hagnell, J., Schander, C. & von Proschwitz, T. Hybridisation in Arionids: the rise of a super slug? British Crop Protection Council Symposium Proceedings: Slugs & Snails: Agricultural, Veterinary & Environmental Perspectives 80, 221–226 (2003).

Hatteland, B. A. et al. Introgression and differentiation of the invasive slug Arion vulgaris from native A. ater. Malacologia 58, 303–321 (2015).

Rowson, B., Anderson, R., Turner, J. A. & Symondson, W. O. C. The slugs of Britain and Ireland: undetected and undescribed species increase a well-studied, economically important fauna by more than 20%. Plos One 9, e91907 (2014).

Kremer, B. P. Weichtiere: Europäische Meeres- und Binnenmollusken. 288 (Mosaik-Verlag, 1990).

CSCF. Database of the Centre Suisse de Cartographie de la Faune. http://www.cscf.ch/ (2014).

Quinteiro, J., Rodriguez-Castro, J., Castillejo, J., Iglesias-Pineiro, J. & Rey-Mendez, M. Phylogeny of slug species of the genus Arion: evidence of Iberian endemics and of the existence of relict species in Pyrenean refuges. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 43, 139–148 (2005).

Arntzen, J. W. et al. Concordant morphological and molecular clines in a contact zone of the Common and Spined toad (Bufo bufo and B. spinosus) in the northwest of France. Frontiers in Zoology 13, 52 (2016).

Wilk, R. J. & Horth, L. A genetically distinct hybrid zone occurs for two globally invasive mosquito fish species with striking phenotypic resemblance. Ecology and Evolution 6, 8375–8388 (2016).

Bastos-Silveira, C., Santos, S. M., Monarca, R., Mathias, M. D. & Heckel, G. Deep mitochondrial introgression and hybridization among ecologically divergent vole species. Molecular Ecology 21, 5309–5323 (2012).

Beysard, M. & Heckel, G. Structure and dynamics of hybrid zones at different stages of speciation in the common vole (Microtus arvalis). Molecular Ecology 23, 673–687 (2014).

Malaspinas, A. S. et al. A genomic history of Aboriginal Australia. Nature 538, 207–214 (2016).

Owens, G. L., Baute, G. J. & Rieseberg, L. H. Revisiting a classic case of introgression: hybridization and gene flow in Californian sunflowers. Molecular Ecology 25, 2630–2643 (2016).

Tsuda, Y. et al. The extent and meaning of hybridization and introgression between Siberian spruce (Picea obovata) and Norway spruce (Picea abies): cryptic refugia as stepping stones to the west? Molecular Ecology 25, 2773–2789 (2016).

Kindler, E., Arlettaz, R. & Heckel, G. Deep phylogeographic divergence and cytonuclear discordance in the grasshopper Oedaleus decorus. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 65, 695–704 (2012).

Rohde, K., Hau, Y., Weyer, J. & Hochkirch, A. Wide prevalence of hybridization in two sympatric grasshopper species may be shaped by their relative abundances. BMC Evolutionary Biology 15, 191 (2015).

Willis, P. M., Ryan, M. J. & Rosenthal, G. G. Encounter rates with conspecific males influence female mate choice in a naturally hybridizing fish. Behavioral Ecology 22, 1234–1240 (2011).

Perry, W. L., Feder, J. L., Dwyer, G. & Lodge, D. M. Hybrid zone dynamics and species replacement between Orconectes crayfishes in a northern Wisconsin lake. Evolution 55, 1153–1166 (2001).

Saarman, N. P. & Pogson, G. H. Introgression between invasive and native blue mussels (genus Mytilus) in the central California hybrid zone. Molecular Ecology 24, 4723–4738 (2015).

Morrison, W. E. & Hay, M. E. Feeding and growth of native, invasive and non-invasive alien apple snails (Ampullariidae) in the United States: invasives eat more and grow more. Biological Invasions 13, 945–955 (2011).

Lockwood, J. L., Hoopes, M. F. & Marchetti, M. P. Invasion Ecology. (Blackwell Publishing, 2007).

Sargent, L. W. & Lodge, D. M. Evolution of invasive traits in nonindigenous species: increased survival and faster growth in invasive populations of rusty crayfish (Orconectes rusticus). Evolutionary Applications 7, 949–961 (2014).

Gibson, M. R. et al. Reproductive biology of Australian acacias: important mediator of invasiveness? Diversity and Distributions 17, 911–933 (2011).

Blattmann, T., Boch, S., Tuerke, M. & Knop, E. Gastropod seed dispersal: an invasive slug destroys far more seeds in its gut than native gastropods. Plos One 8, e75243 (2013).

Knop, E. & Reusser, N. Jack-of-all-trades: phenotypic plasticity facilitates the invasion of an alien slug species. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 279, 4668–4676 (2012).

Kappes, H., Stoll, S. & Haase, P. Differences in field behavior between native gastropods and the fast-spreading invader Arion lusitanicus auct. non MABILLE. Belgian Journal of Zoology 142, 49–58 (2012).

Knop, E., Rindlisbacher, N., Ryser, S. & Grueebler, M. U. Locomotor activity of two sympatric slugs: implications for the invasion success of terrestrial invertebrates. Ecosphere 4, 92 (2013).

Ryser, S., Rindlisbacher, N., Grueebler, M. U. & Knop, E. Differential survival rates in a declining and an invasive farmland gastropod species. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment 144, 302–307 (2011).

Aboim, M. A., Mavarez, J., Bernatchez, L. & Coelho, M. M. Introgressive hybridization between two Iberian endemic cyprinid fish: a comparison between two independent hybrid zones. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 23, 817–828 (2010).

Senn, H. V. et al. Investigating temporal changes in hybridization and introgression in a predominantly bimodal hybridizing population of invasive sika (Cervus nippon) and native red deer (C. elaphus) on the Kintyre Peninsula, Scotland. Molecular Ecology 19, 910–924 (2010).

Allgaier, C. How can two soft bodied animals be precisely connected? A miniature quick-connect system in the slugs, Arion lusitanicus and Arion rufus. Journal of Morphology 276, 631–648 (2015).

Păpureanu, A.-M., Reise, H. & Varga, A. First records of the invasive slug Arion lusitanicus auct. non Mabille (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Arionidae) inRomania. Malacologica Bohemoslovaca 13, 6–11 (2014).

Palmer, A. N. S., Styan, C. A. & Shearman, D. C. A. Foot mucus is a good source for non-destructive genetic sampling in Polyplacophora. Conservation Genetics 9, 229–231 (2008).

Regnier, C., Gargominy, O., Falkner, G. & Puillandre, N. Foot mucus stored on FTA (R) cards is a reliable and non-invasive source of DNA for genetics studies in molluscs. Conservation Genetics Resources 3, 377–382 (2011).

Holsbeek, G., Maes, G. E., De Meester, L. & Volckaert, F. A. M. Conservation of the introgressed European water frog complex using molecular tools. Molecular Ecology 18, 1071–1087 (2009).

Grimm, B. & Paill, W. Spatial distribution and home-range of the pest slug Arion lusitanicus (Mollusca: Pulmonata). Acta Oecologica-International Journal of Ecology 22, 219–227 (2001).

Hausser, J. Bestimmmungsschlüssel der Gastropoden der Schweiz. Vol. 10 (Centre de cartographie de la Faune, 2000).

Aljanabi, S. M. & Martinez, I. Universal and rapid salt-extraction of high quality genomic DNA for PCR-based techniques. Nucleic Acids Research 25, 4692–4693 (1997).

Hall, T. A. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series 41, 95–98 (1999).

Librado, P. & Rozas, J. DnaSPv5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25, 1451–1452 (2009).

Leigh, J. W. & Bryant, D. POPART: full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 6, 1110–1116 (2015).

Zemanova, M. A., Knop, E. & Heckel, G. Development and characterization of novel microsatellite markers for Arion slug species. Conservation Genetics Resources 7, 501–503 (2015).

Peakall, R. & Smouse, P. E. GENALEX 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Molecular Ecology Notes 6, 288–295 (2006).

Goudet, J. FSTAT (Version 1.2): A computer program to calculate F-statistics. Journal of Heredity 86, 485–486 (1995).

Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959 (2000).

Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Molecular Ecology 14, 2611–2620 (2005).

Earl, D. A. & vonHoldt, B. M. Structure Harvester: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conservation Genetics Resources 4, 359–361 (2012).

Nielsen, E. E., Bach, L. A. & Kotlicki, P. Hybridlab (version 1.0): a program for generating simulated hybrids from population samples. Molecular Ecology Notes 6, 971–973 (2006).

Vaha, J. P. & Primmer, C. R. Efficiency of model-based Bayesian methods for detecting hybrid individuals under different hybridization scenarios and with different numbers of loci. Molecular Ecology 15, 63–72 (2006).

Derryberry, E. P., Derryberry, G. E., Maley, J. M. & Brumfield, R. T. hzar: hybrid zone analysis using an R software package. Molecular Ecology Resources 14, 652–663 (2014).

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. http://www.R-project.org (2014).

Szymura, J. M. & Barton, N. H. Genetic analysis of a hybrid zone between the fire-bellied toads, Bombina bombina and Bombina variegata, near Cracow in southern Poland. Evolution 40, 1141–1159 (1986).

Szymura, J. M. & Barton, N. H. The genetic structure of the hybrid zone between the fire-bellied toads Bombina bombina and B. variegata - comparisons between transects and between loci. Evolution 45, 237–261 (1991).

Sutter, A., Beysard, M. & Heckel, G. Sex-specific clines support incipient speciation in a common European mammal. Heredity 110, 398–404 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Susanne Tellenbach for help with the laboratory work, Ulrich Schneppat for valuable advice on slug hunting and Wolfgang Nentwig and Laurent Excoffier for support. This project was funded by the Federal Office for the Environment (BAFU) and University of Bern. M.A.Z. received financial support from the Swiss Association of Academic Women (Schweizerische Verband der Akademikerinnen) and Basel Foundation for Biological Research (Basler Stiftung für biologische Forschung). We thank Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas and Vitor Sousa for valuable comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed this study together. M.A.Z. collected the samples and conducted the molecular work and data analyses under the supervision of G.H. and E.K. The morphological assessment was conducted by M.A.Z. and E.K. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zemanova, M.A., Knop, E. & Heckel, G. Introgressive replacement of natives by invading Arion pest slugs. Sci Rep 7, 14908 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14619-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14619-y

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.