Abstract

Streams are significant sources of CO2 to the atmosphere. Estimates of CO2 evasion fluxes (f CO2) from streams typically relate to the free flowing water but exclude geomorphological structures within the stream corridor. We found that gravel bars (GBs) are important sources of CO2 to the atmosphere, with on average more than twice as high f CO2 as those from the streamwater, affecting f CO2 at the level of entire headwater networks. Vertical temperature gradients resulting from the interplay between advective heat transfer and mixing with groundwater within GBs explained the observed variation in f CO2 from the GBs reasonably well. We propose that increased temperatures and their gradients within GBs exposed to solar radiation stimulate heterotrophic metabolism therein and facilitate the venting of CO2 from external sources (e.g. downwelling streamwater, groundwater) within GBs. Our study shows that GB f CO2 increased f CO2 from stream corridors by [median, (95% confidence interval)] 16.69%, (15.85–18.49%); 30.44%, (30.40–34.68%) and 2.92%, (2.90–3.0%), for 3rd, 4th and 5th order streams, respectively. These findings shed new light on regional estimates of f CO2 from streams, and are relevant given that streamwater thermal regimes change owing to global warming and human alteration of stream corridors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Streams and rivers emit large amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) to the atmosphere. Regional and global estimates of these evasion fluxes are being revised at rapid pace1,2,3,4,5,6. Constraining estimates of CO2 evasion fluxes (f CO2) from streams and rivers is not trivial considering the difficulties associated with the quantification of their surface area, the determination of gas exchange at the interface between the water surface and the atmosphere, and the measurement of the partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2) in the water1,7. Recent studies on the diurnal and seasonal variability of streamwater pCO2 and f CO2 are increasingly highlighting further sources of uncertainty to regional and global estimates of f CO2 8,9,10. Estimates of f CO2 are typically based on discrete or continuous streamwater samples from the active channel, thereby omitting much of the environmental heterogeneity inherent to the corridors of stream ecosystems11.

Geomorphological features ranging from small ripples to bars and meanders diversify hydrodynamic exchange and residence time distributions in streams, thereby adding to their environmental heterogeneity12,13,14. Gravel bars (GBs) induce hydrodynamic exchange where streamwater typically enters the streambed (that is, downwelling) at the head and returns (that is, upwelling) downstream of the GB tail to the streamwater12,15,16. Owing to this enforced hydrodynamic exchange, GBs are sites of increased biogeochemical reactions, as has been shown for dissolved organic carbon (DOC)17,18 and nitrate19. Exposed to solar radiation, GBs can absorb and store heat, which is transferred to the deeper porewater and further to the streamwater upon upwelling or to the groundwater. GBs can thereby impact the thermal regime of entire stream reaches, including their adjacent groundwater20,21. The role for carbon dynamics, including CO2 evasion to the atmosphere from GBs (and likely from other geomorphological features) within stream corridors remains poorly studied at present11.

The aim of our study was to evaluate GBs in subalpine streams as distinct and potentially relevant sources of CO2 to the atmosphere. We further explored temperature distribution within these GBs as a potential driver of f CO2. Based on seasonal and spatial surveys, our findings consistently show that f CO2 from the GBs exceed those from the streamwater. We also found that temperature gradients in the GBs, changing with season, drove f CO2 from the GBs. Including the f CO2 from these ubiquitous geomorphological structures within stream corridors will likely further increase current estimates of regional and global CO2 emissions from streams.

Results

CO2 evasion fluxes

We found the GB in OSB to be a site of increased f CO2 to the atmosphere. Spatially averaged f CO2 from the GB (mean ± standard deviation: 30.72 ± 16.20 mg C m2 h−1) was significantly (t-test: n = 60, t = 4.223, p < 0.001) higher than streamwater f CO2 (20.02 ± 10.89 mg C m2 h−1) (Fig. 1). Over the study period, f CO2 varied significantly (Kruskal-Wallis test, H = 59.99, n = 60, p < 0.001) across the GB, with highest values (median; 25–75 percentile) at the tail (37.29 mg C m−2 h−1; 30.85–44.70 mg C m−2 h−1); followed by the crest (19.12 mg C m−2 h−1; 13.66–30.55 mg C m−2 h−1) and head (14.25 mg C m−2 h−1; 8.87–30.05 mg C m−2 h−1). The crest of the GB was the only location with consistently similar fCO2 to those from the streamwater (17.48 mg C m−2 h−1; 12.08–28.50 mg C m−2 h−1) for all seasons (Wilcoxon test, Tukey HSD for multiple pairwise comparisons, p > 0.05).

Diurnal variation of measured CO2 outgassing fluxes (f CO2) from the head, crest and tail of the GB, and from the streamwater in OSB during summer (A), autumn (B) and winter (C). Uncertainty in calculated f CO2 (not shown) ranged between 0.54% and 1.76%. Global radiation is shown to highlight diurnal patterns.

Evasion fluxes of CO2 also varied seasonally (Fig. 1). Repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant seasonal differences in average f CO2 from the GB (F = 40.37, p < 0.001, n = 19) and the streamwater (F = 6.16, p < 0.01, n = 18). Pairwise comparisons (Tukey HSD) showed overall GB f CO2 to be significantly higher (mean ± standard deviation) in summer (48.78 ± 16.90 mg C m−2 h−1) than in autumn (22.85 ± 6.85 mg C m−2 h−1) and winter (21.89 ± 4.32 mg C m−2 h−1), while they did not significantly differ between autumn and winter. Streamwater f CO2 were significantly lower in winter (13.89 ± 6.51 mg C m−2 h−1) than in summer (24.06 ± 10.62 mg C m−2 h−1) and autumn (22.83 ± 12.28 mg C m−2 h−1).

Average streamwater f CO2 exhibited pronounced diurnal changes, with values (mean ± standard deviation) being highest in the morning (5 am: 27.65 ± 10.01 mg C m−2 h−1) and in the evening (8 pm: 23.29 ± 7.48 mg C m−2 h−1) and lowest in the early afternoon (2 pm: 10.96 ± 7.25 mg C m−2 h−1). Unexpectedly, average f CO2 from the GB did not significantly vary diurnally within or across seasons (Kruskal-Wallis H test, H = 0.423, p = 0.66, n = 18).

Groundwater can deliver CO2 from soil respiration to the stream22. Our mixing model, based on time series of electrical conductivity, revealed only minor contributions (<14%) of groundwater to the GB in OSB, which did not correlate (Pearson’s product moment correlation: p > 0.05 for all locations and seasons, except p < 0.05 for the crest in summer) with f CO2 from the GB (see Supplementary Fig. S6). We therefore argue that groundwater likely does not substantially contribute to the pool of CO2 and its dynamics in the GB of our study stream.

DOC dynamics

Streamwater DOC concentration did not vary substantially (Kruskal-Wallis H-test, H = 0.779, p = 0.677, n = 19) across seasons (median; 25–75 percentile): summer (1.23 mg C L−1; 1.15–1.36 mg C L−1); autumn (1.27 mg C L−1; 1.19–1.31 mg C L−1) and winter (1.21 mg C L−1; 1.16–1.27 mg C L−1). Depth averaged (0.75 m and 1.25 m) DOC concentrations along the GB (at the GB head, crest and tail) and in the streamwater throughout the year, significantly varied (Kruskal-Wallis H test, H = 35.60, p < 0.001, n = 53). Throughout the year and across seasons, DOC concentrations at the GB head (1.36 mg C L−1; 1.27–1.44 mg C L−1) and tail (1.37 mg C L−1; 1.26–1.49 mg C L−1) were statistically indistinguishable, and were significantly higher than at the GB crest (1.27 mg C L−1; 1.21–1.36 mg C L−1) and streamwater (1.23 mg C L−1; 1.16–1.30 mg C L−1). Seasonally, GB depth averaged DOC concentrations (mean ± standard deviation) peaked in autumn (head: 1.39 ± 0.18 mg C L−1, crest: 1.42 ± 0.32 mg C L−1 and tail: 1.55 ± 0.41 mg C L−1) and were lowest in winter (head: 1.33 ± 0.10 mg C L−1, crest: 1.29 ± 0.16 mg C L−1 and tail: 1.28 ± 0.09 mg C L−1), and at intermediate levels in summer (head: 1.41 ± 0.28 mg C L−1, crest: 1.28 ± 0.19 mg C L−1 and tail: 1.55 ± 0.40 mg C L−1). DOC concentration and its seasonal variability (coefficient of variation) were typically higher within the upper section (0.75 m) of the GB (see Supplementary Table S1) than at the lower section (1.25 m). Overall, depth and spatially averaged GB porewater DOC concentration (that is the average of all GB locations and depths, per sampling time) did not correlate with GB f CO2 (r = 0.06, p = 0.661, n = 52) across seasons.

Thermal regime in the OSB gravel bar

Average streamwater temperature in OSB was 9.64 ± 0.74 °C, 7.47 ± 0.51 °C and 6.53 ± 0.64 °C during the summer, autumn and winter sampling, respectively. Corresponding temperatures of the adjacent groundwater averaged 12.16 ± 0.14 °C, 8.60 ± 0.07 °C and 4. 82 ± 0.90 °C (Fig. 2). During spring and summer, the temperature of the GB surface followed distinct diurnal fluctuations and was consistently higher than both stream and groundwater temperature (Fig. 2, see Supplementary Fig. S4). During these seasons, particularly at baseflow, temperatures within the saturated sediment (that is, ca. 0.7 to 1.0 m below surface) were relatively stable, exceededing the temperature of the streamwater and groundwater during almost 20% of the year (see Supplementary Fig. S4). Storm events transiently collapsed vertical gradients, which recovered rapidly during flow recession (see Supplementary Fig. S4).

Temporal patterns of discharge and global radiation (A), streamwater temperature (B), hillslope groundwater (C), and of vertical temperature gradients at the GB head (D), crest (E) and tail (F) in summer, autumn and winter when f CO2 were measured on the GB in Oberer Seebach (OSB). The lines in panels D to F indicate the interface between the saturated and unsaturated GB sediments. Missing data are indicated by white spots.

Temperature within the GB varied with depth and exhibited marked seasonal and diurnal patterns that also changed over the GB from its head to the crest and tail (Fig. 2, see Supplementary Fig. S4). Depth gradients (mean ± standard deviation) were pronounced in winter (−0.025 ± 0.009 °C cm−1), with lower temperatures close to the GB surface than in the streamwater and groundwater, a difference that became alleviated with depth. These pronounced gradients were broken and reversed in summer when porewater below the GB surface became warmer than the streamwater (see Supplementary Fig. S4). Depth gradients in summer were most pronounced at the head (0.017 ± 0.016 °C cm−1) and crest (0.019 ± 0.008 °C cm−1) of the GB (see Supplementary Fig. S4). With the onset of autumn, the depth gradients collapsed and temperature patterns in the GB became more homogenous and comparable to streamwater temperature.

Temperature as a driver of CO2 evasion fluxes

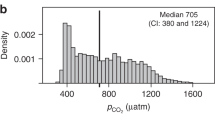

Because ecosystem metabolism contributions to f CO2 and the solubility and release of CO2 depend on temperature23, we explored the effect of temperature within the GB on f CO2 to the atmosphere. We found that the average temperature of the saturated GB sediments explained 62% (n = 56, p < 0.001) of the variation in f CO2 across all three seasons (Fig. 3A). Discharge, an important driver of pCO2 in streams9, did not increase the predictive explanatory power of this simple model (see Supplementary Fig. S5). As GBs are exposed to the atmosphere and solar radiation, and can store thermal energy, which in turn may be transferred to deeper sediment layers20,21, we further tested if vertical temperature gradient, rather than absolute temperature, affect f CO2 from the GB in OSB. We found that vertical temperature gradient explained 54% (p < 0.001) of the variation in f CO2 from the GB across seasons (Fig. 3B).

Relationship between CO2 outgassing fluxes (f CO2) and average absolute temperature (A) and vertical temperature gradients (B) in the gravel bar in OSB, and for ancillary GBs within the Ybbs and Erlauf catchments (C). Filled circles (3a & 3b) represent diurnal gravel bar f CO2 (averaged over the head, crest and tail), colored by season. In Fig. 3c black circles represent gravel bar f CO2 while blue circles refer to the f CO2 from the respective streamwater. Site Ysteinb (open circles in 3c) was excluded from exponential fit, as it represents a dammed stream with a sandy island. The black lines represent the exponential model with its 95% confidence limits in blue, while the red lines denote the 95% confidence intervals for the observed data. Horizontal and vertical error bars represent standard deviations. No error bars are shown in panel C as points represent averages of discrete single diurnal (7 am and 6 pm) samples.

Our spatial survey on the ancillary GBs (n = 13) provided a similar relationship (r2 = 0.73, p < 0.001) between vertical temperature gradients and average diurnal f CO2 (Fig. 3C) as we found from the temporal variation on the GB in OSB (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, this extended analysis confirmed that f CO2 from the GBs (mean ± standard deviation: 14.56 ± 7.24 mg C m−2 h−1) were significantly (t-test, t = 3.40, n = 13, p < 0.01) higher than average f CO2 from their respective streamwater (6.85 ± 3.81 mg C m−2 h−1). During this 10-day survey, early morning (evening) streamwater and GB surface temperature averaged 11.7 ± 1.4 °C (14.4 ± 1.8 °C) and 14.4 ± 1.4 °C (20.6 ± 2.8 °C), respectively, across all sites (see Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Methods). Given these small spatial temperature ranges, we exclude absolute temperature differences between sites as a possible driver of the observed relationship (Fig. 3C).

Extrapolation of f CO2 from gravel bars

We extrapolated our findings from individual GBs to the scale of the Ybbs River system using Monte-Carlo simulation and resampling techniques, and based on the ratio of GB f CO2 to streamwater f CO2 , GB area coverage and previously published median streamwater f CO2 data from the same system (3rd-order streams: 46.0 mg C m−2 h−1; 4th-order streams: 43.5 mg C m−2 h−1; 5th-order streams: 50.4 mg C m−2 h−1)10. Average relative coverage of GBs per stream order varied from 25.97% ± 5.52% to 16.12% ± 2.69% and 5.39% ± 0.73% for 3rd, 4th and 5th-order streams, respectively; we surveyed four 3rd, three 4th and one 5th-order stream for this analysis. Similarly, ratios of GB f CO2 to streamwater f CO2 varied from 1.64 ± 0.78, 2.99 ± 2.03 and 1.54 ± 0.13 for 3rd, 4th and 5th-order streams. We estimated that the inclusion of f CO2 from GBs increases stream corridor f CO2 [median, (95%. confidence interval)] within the Ybbs River network by 16.69%, (15.85–18.49%); 30.44%, (30.40–34.68%) and 2.92%, (2.90–3.0%) for 3rd, 4th and 5th-order streams, respectively at baseflow (Supplementary Table S3). Our estimates of f CO2 from the stream corridor showed a higher sensitivity to GB f CO2 : streamwater f CO2 ratios (correlation = 0.98, 0.97 and 0.85, re-sampled n = 1000) than % GB coverage (correlation = 0.16, 0.21 and 0.53, re-sampled n = 1000) for 3rd, 4th and 5th-order streams in the Ybbs network, respectively.

Discussion

Gravel bars are important geomorphological features within stream corridors. Our findings from a broad range of GBs across several stream orders, show that mean diurnal f CO2 from GBs were on average 2.19 ± 1.43 times higher than the f CO2 from streamwater. Thereby, these results reveal GBs as hitherto potentially significant sources of CO2 to the atmosphere and link these critical carbon fluxes to the thermal regime in GBs. Overall, our chamber measurements produced fluxes closely bracketed by long-term data from OSB9 and spatial surveys in the same catchment10 as inferred from CO2 partial pressure in the streamwater and the atmosphere, and from gas exchange velocity.

The stream corridor, including its GBs, is a transition zone between the active stream channel and the adjacent terrestrial environment24. As such, GBs and the terrestrial environment share physical properties relevant for gas exchange, such as elevated gas diffusivity25,26,27,28,29,30. A major difference between GBs and the soil environment is that GBs contain a continuously saturated near-surface zone, subject to hydrodynamic exchange with the streamwater, and that the thermal regime within GBs is driven by a suite of hydrodynamic and geomorphological processes20,31,32.

Exposed to solar radiation, the GB surface accumulates heat that can be advected downwards to deeper sediment layers. During extended baseflow in summer, heat advection can lead to strong temperature-depth gradients where cooler groundwater entering OSB from the left hillslope and mixing with porewater in the GB (see Supplementary Fig. S3) depresses the advective effect in deeper layers. We also noticed that storm events can transiently erode established temperature gradients in summer. Whereas in autumn and winter, owing to reduced solar radiation and low air temperature diurnality and unsteady flow, vertical hydraulic gradients within the GB do not establish, or even periodically inverse (see Supplementary Fig. S4). We argue that these thermal dynamics and their effects on stream biogeochemistry is comparable to the ecosystem impacts of the thermal stratification and mixing in lakes33.

We consider vertical temperature gradients within the GB as a direct measure of the heating (or cooling) from the GB surface toward the subsurface and driver of temperature mediated processes within GBs. Temperature distribution in GBs played a major role for f CO2 from a broad range of GBs differing in size, geometry and positioning within the stream corridor. This is likely due to the catalyzing effect of absolute temperature on heterotrophic metabolism23,34, but also to the effect of temperature gradients on porewater CO2 solubility35 and the resulting diffusive flux. The observed vertical temperature gradients and fact that permanent water table temperatures exceeded the temperature of the streamwater and groundwater during almost 20% of the year suggest that the GB surface heats up in response to the sum diurnal fluctuations in air temperature and solar radiation, particularly in spring and summer. Downwelling streamwater can transport heat absorbed from the warmer GB surface downwards, while extended travel times within the GB should facilitate the warming of streamwater near the heated GB surface and the advective transfer of this heat to deeper layers.

Our notion of solar radiation and air temperature generating the thermal gradients in the GB is also supported by the diurnal patterns of temperature gradients during summer. In summer the heat transfer reached down to 1m depth to become alleviated by mixing with cooler groundwater (Fig. 2, see Supplementary Fig. S4). These temperature gradients explained (>70%) of the variation in f CO2 from the various GBs across the study catchments. Because streams have distinctive temperature regimes, we argue that temperature gradients, rather than absolute temperature, are likely a more transferable parameter for assessing the influence of temperature on f CO2 across a wide range of streams. Given the small range of streamwater and GB surface temperatures across all study sites, we are confident that the observed pattern was not driven merely by temporal variation but rather by processes that actually drive f CO2.

The observed diurnal patterns of f CO2 from the GB are likely due to the combined effects of in-stream respiration, GB metabolism and the delivery of respiratory CO2 from adjacent soils via groundwater22. We suggest that streamwater downwelling close to the head of the GB and enriched in CO2 from over-night respiration in the stream9,36 spikes the GB subsurface water, itself CO2-enriched by groundwater inputs. This would lead to a temporally lagged increase in GB f CO2 around 2 pm. Conversely, lower overnight (5 am) f CO2 from the GB may be attributable to downwelling streamwater that is low in CO2 owing to photosynthesis and degassing during the daytime9 and is flowing through the GB at night. These time-lagged CO2 outgassing patterns are in fact corroborated by estimated lag times (0.3 to 17 h) in electrical conductivity between downwelling streamwater and the GB head, crest and tail (see Supplementary Table S4), and are likely the reason for overall lack of diurnal patterns of GB f CO2 in OSB. Our findings suggest no major contributions from groundwater discharge to the porewater in the GB in OSB. However, groundwater adjacent to OSB is typically super-saturated in CO2 9, and may therefore still be a significant source of CO2 from the catchment to the f CO2 from the GB.

Within the stream corridor, GBs represent a direct interface between groundwater, typically enriched in CO2, and the atmosphere. Fluxes of CO2 from the OSB gravel bar were higher and more variable than that of the stream. Higher f CO2 from the GBs than from the adjacent streamwater may be attributable to enhanced biogeochemical reaction rates in the GB sediments. In fact, several studies have highlighted the streambed and particularly GBs as sites of increased metabolism and nutrient cycling, owing to increased residence time and large reactive surface areas36,37,38,39; these processes may ultimately contribute to the observed f CO2 . Furthermore, recent findings by Rasilo et al.40 showed that a substantial percentage of CO2 within the streambed originates from sub-surface oxidation of soil derived DOC and CH4 in groundwater, in addition to direct transport of CO2 from groundwater to the streambed. Thereby, CO2 from soil respiration41 and/or chemical weathering42 in the catchment can evade through the porous system of the unsaturated sediments in the GBs.

GBs also trap and burry organic matter during floods, a process that can be enhanced by vegetation growing on the GBs43, and potentially fuel respiration in the sediments44. Here we have not studied the distribution of particulate organic carbon in the sediments and can therefore not assess its effect on the production of respiratory CO2 within GBs. However, our results do not support a significant relationship between DOC concentration in the GB porewater and f CO2 from the GB. We argue therefore that DOC as the intermediary to the carbon cycle2 is likely not a major driver or limiting factor of f CO2 released from the GB in OSB. Furthermore, f CO2 did not significantly vary with the small changes in stream discharge and water level within the GB (Fig. 2), indicating that variability in related drivers of f CO2 such as sediment saturation26,29,30 and gas diffusivity27,29 were likely insignificant during sampling at OSB.

While our results suggest temperature as an important driver of GB and streamwater f CO2 , we cannot exclude the possibility of a range of potentially unaccounted drivers of CO2 outgassing from GBs, some of which may also co-vary with temperature and season. For instance, respiration is typically controlled by a combination of retention time45,46,47, temperature48,49,50 and limiting reactant concentrations (e.g., oxygen, labile DOC, total nitrogen and phosphorous)51,52,53. While GB sediments within OSB were never found to be oxygen limited, oxygen concentrations varied spatially and seasonally (see Supplementary Table S1). We suspect that high temperatures in summer and downwelling of bioavailable, autochthonous organic carbon2,54,55 would stimulate heterotrophic respiration within the GB56. This would result in summer oxygen lows and peak levels of CO2 outgassing as observed in our study57 (see Supplementary Table S1). During autumnal leaf litter fall, concentrations of DOC (possibly also particulate organic carbon) in the OSB stream and sub-surface peak57 (see Supplementary Table S1). Although soil-derived DOC comprises a wide range of components, including those readily degradable by bacteria58,59,60, lower temperatures and the prevalence of comparatively “less bioavailable” organic carbon stream- and soilwater inputs61,62,63 during autumn would likely lead to decreased microbial activity and autumn f CO2 . Furthermore, several studies have shown that the frequency and intensity of sediment re-wetting are determinants of sub-surface DOC quality64,65,66,67. This variation would likely control microbial activity within the sediments and additionally contribute to the spatial and temporal variability of CO2 outgassing on diurnal to sub-seasonal timescales. Following these notions, a dependence of f CO2 on seasonally varying availability of labile DOC, rather than total DOC within the GB can be proposed.

Our GB coverage survey at baseflow revealed that GB spacing (corresponding to 3 to 6 stream widths; see Supplementary Table S3) was bracketed by 5 to 7 channel widths for regular pool spacing in natural streams68,69,70 and by 1 to 4 channel widths for low-order stream step-pool reaches71,72. We acknowledge that our upscaling estimates based on the assumption of an elliptical GB area, and rough estimates of wetted stream area (see Supplementary Methods) may lead to an unknown error in our GB f CO2 calculations. The low contribution and small variability of GB f CO2 in the 5th order stream is likely an underestimate owing to the relatively short reach length (1 km) and low number (n = 9) of GBs sampled (see Supplementary Table S3). The high sensitivity of our calculations to GB f CO2 : streamwater f CO2 ratios was primarily due to its large variability (see Supplementary Table S3), an inherent characteristic of stream corridors over space and time9,10, and its direct influence as a multiplicative factor on f CO2 from the stream corridor. Nevertheless, our findings highlight the relevance of GBs for f CO2 from entire stream networks at baseflow.

Our findings expand current knowledge on the relationships between hydrodynamics, thermal dynamics, and carbon fluxes within stream corridors32,73,74. Accounting for f CO2 from the corridor and notably from the GBs, rather than from the active channel solely14, will likely increase current f CO2 estimates from streams5 on the catchment to regional scale. As highlighted by Wohl and colleagues11, carbon dynamics in stream and river corridors is particularly prone to human alterations. Our findings add yet another dimension to this. Our study calls for wider surveys to further assess and predict the relevance of GBs for CO2 evasion fluxes from stream ecosystems, including their corridor, as extended baseflow and droughts, owing to global warming, may lead to increased exposure of GBs to solar radiation.

Material and Methods

Field sites

Our core study site was a point GB (ca. 42 m long, 8 m wide at baseflow (430 L s−1) in the 3rd-order gravel stream Oberer Seebach (OSB; Ybbs River catchment, Austria) (see Supplementary Figs S1 & S2, Supplementary Methods). OSB is a cold-water stream (6.87 °C, average 2010 to 2016) with temperatures ranging from 0.4 °C in winter to 19.9 °C during summer baseflow. The OSB flow regime (average discharge: 752 L s−1, 2010 to 2016) is characterized by snowmelt in spring and pronounced storm flow (up to 28,065 L s−1) in summer. Topography adjacent to the OSB channel influences subsurface hydrological flow paths, with groundwater flowing from the orographic left hillslope through the OSB streambed where it mixes with streamwater or partially recharges groundwater in the opposite right floodplain57 (see Supplementary Fig. S3). The hydraulic conductivity (mean ± standard deviation) of GB sediments in OSB varied from 3.9 ± 2.6 × 10−4 m s−1 to 1.1 ± 0.5 × 10−3 m s−1 and 8.9 ± 4.5× 10−4 m s−1 at the head, crest and tail, respectively. Average water travel times (measured at 0.75 m and 1.25 m below surface) within the GB approximated 10 h, 1.5 h and 1.3 h to the head, crest and tail, respectively (see Supplementary Table S4 & Supplementary Methods).

We expanded our study sites from OSB to 12 additional GBs within 2nd to 5th-order streams throughout the catchments of the Ybbs River and the Grosse Erlauf River where we focused on discrete sampling in time during August and September 2016 (see Supplementary Fig. S1, Supplementary Table S2). We extended our f CO2 measurements to the catchment scale (see Supplementary Fig. S1), estimating stream area and percentage stream coverage by GBs across mid-order streams (2nd to 5th) within the Ybbs catchment during a roaming survey (~0.25–0.60 km for 2nd order streams and ~1.0 km for 3rd–5th order streams), complimented by median f CO2 data for ~150 stream reaches within the Ybbs catchment10 (see Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Fig. S1).

Temperature distribution

We measured temperature every 10 minutes at 8 depth levels (0.07 m above to 1 m below surface) at the head, crest and tail of the GB in OSB using LogTrans6-GPRS sensors (Umwelt und Ingenieurtechnik GmbH, Dresden, Germany–range: −20 °C–50 °C, accuracy: ±0.1 °C). Temperature of shallow groundwater was measured in three wells adjacent to OSB at a fixed depth below the long-term minimum water level; streamwater temperature was measured upstream and downstream of the GB. Groundwater and streamwater temperatures were monitored at 10 and 30 min intervals, respectively. We also recorded air temperature (HOBO U30, Onset Computer Co., MA) and global radiation (ZAMG, Austria) as potential drivers of the thermal regime within the GB at OSB. Temperature in the ancillary GBs was measured at the surface, at 0.25 and 0.50 m depth using piezometers and a TSUB21-CL5 (PyroScience GmbH, Aachen, Germany) dipping probe. Vertical gradients of temperature were calculated as the difference between the temperature at the GB surface and at 1-m and 0.5-m depth for OSB and the ancillary sites, respectively, and normalized by depth.

Porewater chemistry

We sampled porewater from 13 piezometers (0.75 and 1.25 m below sediment surface) distributed over the GB in OSB and analyzed it for DOC (Sievers TOC Analyzer GE) and for electrical conductivity (WTW Cond 3310, Weilheim, Germany) (see Supplementary Methods).

CO2 evasion fluxes

f CO2 from the streamwater, and from the head, crest and tail of each GB were determined using flux chambers7,75. On the OSB GB, we measured diurnal f CO2 (5 am, 2 pm, 8 pm) at baseflow over 6 to 7 consecutive days in August and September 2015, November 2015 and March 2016, respectively. At the ancillary sites, discrete f CO2 measurements at 8 am (7 to 9 am) and 6 pm (5 to 7 pm) were taken within one week in August and September 2016 during baseflow (see Supplementary Table S2). At the start of each incubation, CO2 in the chamber was equalized with air, and CO2 concentrations recorded every minute for a minimum of 0.5 hours. f CO2, was calculated from f CO2 = [CO2]mol × RMMC × 1000]/(A × T), where RMMC is the relative molar mass of carbon, A is the surface area (m2) covered by the chamber, and T is the incubation period (h). The molar CO2 concentration [CO2]mol was determined as ΔCO2 (ppmv) × 10−6 × V chamber/V m, where V chamber refers to the volume (L) of the chamber and V m refers to the molar gas volume defined as R × T/p, where R is the gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1) and p the gas pressure (hPa). The gradient of the linear section of CO2 increase over 10–30 minutes was used to derive f CO2, with visual inspection of each CO2 curve to confirm consistent linearity. Uncertainty in individual f CO2 measurements was calculated via equipment error propagation (see Supplementary Methods), where atmospheric pressure, estimated from altitude, was assumed constant (930 hPa).

To assess the implications of GBs as sites of increased f CO2 for an entire stream network, we first estimated the percentage areal cover of GBs within the wetted channel boundaries of 2nd to 5th order streams of the Ybbs catchment. We used streamwater f CO2 data derived from a detailed catchment stream study (n = 148) of the Ybbs catchment10, assuming similar stream order-specific proportionality between GB and streamwater f CO2 to that determined in our catchment-wide f CO2 survey in order to estimate corresponding GB f CO2 . Correcting catchment-wide streamwater f CO2 for percentage area presence of GBs, we calculated the increase in overall stream corridor f CO2 considering GB contributions to f CO2 under baseflow conditions. We utilized a Monte Carlo approach to constrain our estimates (see Supplementary Methods) of increase in stream corridor f CO2 . As a result of only one 2nd order stream being sampled during the Ybbs/Grosse Erlauf catchment survey, 2nd and 3rd order stream data were combined for calculations.

References

Cole, J. J. et al. Plumbing the Global Carbon Cycle: Integrating Inland Waters into the Terrestrial Carbon Budget. Ecosystems 10, 171–184 (2007).

Battin, T. J. et al. Biophysical controls on organic carbon fluxes in fluvial networks. Nat. Geosci. 1, 95–100 (2008).

Battin, T. J. et al. The boundless carbon cycle. Nat. Geosci. 2, 598–600 (2009).

Butman, D. & Raymond, P. A. Significant efflux of carbon dioxide from streams and rivers in the United States. Nat. Geosci. 4, 839–842 (2011).

Raymond, P. A. et al. Global carbon dioxide emissions from inland waters. Nature 503, 355–359 (2013).

Lauerwald, R., Laruelle, G. G., Hartmann, J., Ciais, P. & Regnier, P. A. G. Global Biogeochemical Cycles. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 29, 534–554 (2015).

Bastviken, D., Sundgren, I., Natchimuthu, S., Reyier, H. & Gålfalk, M. Technical Note: Cost-efficient approaches to measure carbon dioxide (CO2) fluxes and concentrations in terrestrial and aquatic environments using mini loggers. Biogeosciences 12, 3849–3859 (2015).

Wallin, M. B. et al. Evasion of CO2 from streams – The dominant component of the carbon export through the aquatic conduit in a boreal landscape. Glob. Chang. Biol. 19, 785–797 (2013).

Peter, H. et al. Scales and drivers of temporal pCO2 dynamics in an Alpine stream. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 119, 1078–1091 (2014).

Schelker, J., Singer, G. A., Ulseth, A. J., Hengsberger, S. & Battin, T. J. CO2 evasion from a steep, high gradient stream network: importance of seasonal and diurnal variation in aquatic pCO 2 and gas transfer. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2 (2016).

Wohl, E., Hall, R. O. Jr., Lininger, K. B., Sutfin, N. A. & Walters, D. M. Carbon dynamics of river corridors and the effects of human alterations. Ecol Monogr. Accepted A (2017).

Stonedahl, S. H., Harvey, J. W., Wörman, A., Salehin, M. & Packman, A. I. A multiscale model for integrating hyporheic exchange from ripples to meanders. Water Resour. Res. 46, 1–14 (2010).

Boano, F. et al. Hyporheic flow and transport processes: Mechanisms, models, and biogeochemical implications. Rev. Geophys. 52, 603–679 (2014).

Harvey, J. & Gooseff, M. River corridor science: Hydrologic exchange and ecological consequences from bedforms to basins. Water Resour. Res. 51, 6893–6922 (2015).

Hester, E. T. & Doyle, M. W. In-stream geomorphic structures as drivers of hyporheic exchange. Water Resour. Res. 44 (2008).

Trauth, N., Schmidt, C., Vieweg, M., Oswald, S. E. & Fleckenstein, J. H. Hydraulic controls of in-streamgravel bar hyporheic exchange and reactions. Water Resour. Res. 51, 2243–2263 (2015).

Findlay, S., Strayer, D., Goumbala, C. & Gould, K. Metabolism of streamwater dissolved organic carbon in the shallow hyporheic zone. Limnol. Oceanogr. 38, 1493–1499 (1993).

Findlay, S. & Sobczak, W. V. Variability in Removal of Dissolved Organic Carbon in Hyporheic Sediments. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 15, 35–41 (1996).

Dahm, C. N., Grimm, N. B., Marmonier, P., Vallet, M. H. & Vervier, P. Nutient dynamics at the interface between surface waters and groundwaters. (1998).

Burkholder, B. K., Grant, G. E., Haggerty, R., Khangaonkar, T. & Wampler, P. J. Influence of hyporheic flow and geomorphology on temperature of a large, gravel-bed river, Clackamas River, Oregon, USA. Hydrol. Process. 22, 941–953 (2008).

Arrigoni, A. S. et al. Buffered, lagged, or cooled? Disentangling hyporheic influences on temperature cycles in stream channels. Water Resour. Res. 44 (2008).

Hotchkiss, E. R. et al. Sources of and processes controlling CO2 emissions change with the size of streams and rivers. Nat. Geosci. 8, 696–699 (2015).

Yvon-Durocher, G., Jones, J. I., Trimmer, M., Woodward, G. & Montoya, J. M. Warming alters the metabolic balance of ecosystems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B Biol. Sci. 365, 2117–2126 (2010).

Poole, G. C. Fluvial landscape ecology: Addressing uniqueness within the river discontinuum. Freshw. Biol. 47, 641–660 (2002).

Raich, J. W. & Schlesinger, W. H. The global carbon dioxide flux in soil respiration and its relationship to vegetation and climate. Tellus 44, 81–99 (1992).

Davidson, E. A., Belk, E. & Boone, R. D. Soil water content and temperature as independent or confounded factors controlling soil respiration in a temperate mixed hardwood forest. Glob. Chang. Biol. 4, 217–227 (1998).

Moldrup, P., Olsen, T., Schjønning, P., Yamaguchi, T. & Rolston, D. E. Predicting the gas diffusion coefficient in undisturbed soil from soil water characteristics. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. 64, 94–100 (2000).

Kang, S., Lee, D., Lee, J. & Running, S. W. Topographic and climatic controls on soil environments and net primary production in a rugged temperate hardwood forest in Korea. Ecol. Res. 21, 64–74 (2006).

Pacific, V. J., McGlynn, B. L., Riveros-Iregui, D. A., Welsch, D. L. & Epstein, H. E. Landscape structure, groundwater dynamics, and soil water content influence soil respiration across riparian-hillslope transitions in the Tenderfoot Creek Experimental Forest, Montana. Hydrol. Process. 25, 811–827 (2011).

Pacific, V. J., McGlynn, B. L., Riveros-Iregui, D. A., Welsch, D. L. & Epstein, H. E. Variability in soil respiration across riparian-hillslope transitions. Biogeochemistry 91, 51–70 (2008).

Marzadri, A., Tonina, D. & Bellin, A. Effects of stream morphodynamics on hyporheic zone thermal regime. Water Resour. Res. 49, 2287–2302 (2013).

Norman, F. A. & Cardenas, M. B. Heat transport in hyporheic zones due to bedforms: An experimental study. Water Resour. Res. 3568–3582, https://doi.org/10.1002/2013WR014673.Received (2014).

Boehrer, B. & Schultze, M. Stratification of lakes. Rev. Geophys. 46 (2008).

Hlaváčová, E., Rulík, M. & Čáp, L. Anaerobic microbial metabolism in hyporheic sediment of a gravel bar in a small lowland stream. River Res. Appl. 21, 1003–1011 (2005).

Carroll, J. J., Slupsky, J. D. & Mather, A. E. The solubility of carbon dioxide in water.pdf. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data1 20, 1201–1209 (1991).

Hlaváčová, E., Rulík, M., Čáp, L. & Mach, V. Greenhouse gas (CO2, CH4, N2O) emissions to the atmosphere from a small lowland stream in Czech Republic. Arch. für Hydrobiol. 165, 339–353 (2006).

Findlay, S. Importance of surface-subsurface exchange in stream ecosystems: The hyporheic zone. Limnol. Oceanogr. 40, 159–164 (1995).

Boano, F., Revelli, R. & Ridolfi, L. Effect of streamflow stochasticity on bedform-driven hyporheic exchange. Adv. Water Resour. 33, 1367–1374 (2010).

Houghton, R. a. The worldwide extent of land-use change: In the last few centuries, and particularly in the last several decades, effects of land-use change have become global. Bioscience 44, 305–313 (1994).

Rasilo, T., Hutchins, R. H. S. & Ruiz-González, C. & delGiorgio, P. A. Transport and transformation of soil-derived CO2, CH4 and DOC sustain CO2 supersaturation in small boreal streams. Sci. Total Environ. 579, 902–912 (2017).

Johnson, M. S. et al. CO 2 efflux from Amazonian headwater streams represents a significant fate for deep soil respiration. 35, 1–5 (2008).

Crawford, J. T., Dornblaser, M. M., Stanley, E. H., Clow, D. W. & Striegl, R. G. Source limitation of carbon gas emissions in high-elevation mountain streams and lakes. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 120, 952–964 (2015).

Bätz, N., Verrecchia, E. P. & Lane, S. N. The role of soil in vegetated gravelly river braid plains: More than just a passive response? Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 40, 143–156 (2015).

Pusch, M. The metabolism of organic matter in the hyporheic zone of a mountain stream, and its spatial distribution. Hydrobiologia 323, 107–118 (1996).

Brunke, M., Brunke, M., Gonser, T. & Gonser, T. The ecological significance of exchange processes between rivers and groundwater. Freshw. Biol. 37, 1–33 (1997).

Zarnetske, J. P., Haggerty, R., Wondzell, S. M. & Baker, M. a. Dynamics of nitrate production and removal as a function of residence time in the hyporheic zone. J. Geophys. Res. 116, G01025 (2011).

Gomez, J. D., Krause, S. & Wilson, J. L. Effect of low-permeability layers on spatial patterns of hyporheic exchange and groundwater upwelling. Water Resour. Res. 50, 5196–5215 (2014).

Boulton, A. J., Findlay, S., Marmonier, P., Stanley, E. H. & Valett, H. M. the Functional Significance of the Hyporheic Zone in Streams and Rivers. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 29, 59–81 (1998).

Acuña, V., Wolf, A., Uehlinger, U. & Tockner, K. Temperature dependence of stream benthic respiration in an Alpine river network under global warming. Freshw. Biol. 53, 2076–2088 (2008).

Marzadri, A., Tonina, D. & Bellin, A. Quantifying the importance of daily stream water temperature fluctuations on the hyporheic thermal regime: Implication for dissolved oxygen dynamics. J. Hydrol. 507, 241–248 (2013).

Mulholland, P. J. et al. Stream denitrification across biomes and its response to anthropogenic nitrate loading. Nature 452, 202–205 (2008).

Deforet, T. et al. Do parafluvial zones have an impact in regulating river pollution? Spatial and temporal dynamics of nutrients, carbon, and bacteria in a large gravel bar of the Doubs River (France). Hydrobiologia 623, 235–250 (2009).

Bardini, L., Boano, F., Cardenas, M. B., Revelli, R. & Ridolfi, L. Nutrient cycling in bedform induced hyporheic zones. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 84, 47–61 (2012).

Battin, T. J., Kaplan, L. A., Newbold, D. J. & Hendricks, S. P. A mixing model analysis of stream solute dynamics and the contribution of a hyporheic zone to ecosystem function. Freshw. Biol. 48, 1–20 (2003).

Fasching, C., Ulseth, A. J., Schelker, J., Steniczka, G. & Battin, T. J. Hydrology controls dissolved organic matter export and composition in an Alpine stream and its hyporheic zone. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61, 558–571 (2016).

Stegen, J. C. et al. Groundwater-surface water mixing shifts ecological assembly processes and stimulates organic carbon turnover. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–12 (2016).

Battin, T. J. Hydrologic flow paths control dissolved organic carbon fluxes and metabolism in an alpine stream hyporheic zone. Water Resour. Res. 35, 3159–3169 (1999).

Guillemette, F., McCallister, S. L. & del Giorgio, P. A. Differentiating the degradation dynamics of algal and terrestrial carbon within complex natural dissolved organic carbon in temperate lakes. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 118, 963–973 (2013).

Fasching, C., Behounek, B., Singer, G. A. & Battin, T. J. Microbial degradation of terrigenous dissolved organic matter and potential consequences for carbon cycling in brown-water streams. Sci. Rep. 4, 1–7 (2014).

Lapierre, J. F. & del Giorgio, P. A. Partial coupling and differential regulation of biologically and photochemically labile dissolved organic carbon across boreal aquatic networks. Biogeosciences 11, 5969–5985 (2014).

Baker, M. A., Valett, H. M. & Dahm, C. N. Organic Carbon Supply and Metabolism in a Shallow Groundwater Ecosystem. Ecology 81, 3133–3148 (2000).

Mei, Y., Hornberger, G. M., Kaplan, L. A., Newbold, J. D. & Aufdenkampe, A. K. The delivery of dissolved organic carbon froma forested hillslope to a headwater streamin southeastern Pennsylvania, USA. Water Resour. Res. 50, 5774–5796 (2014).

McLaughlin, C. & Kaplan, L. A. Biological lability of dissolved organic carbon in stream water and contributing terrestrial sources. Freshw. Sci. 32, 1219–1230 (2013).

Marschner, B. & Bredow, A. Temperature effects on release and ecologically relevant properties of dissolved organic carbon in sterilised and biologically active soil samples. Soil Biol. Biochem. 34, 459–466 (2002).

Chow, A. T., Tanji, K. K., Gao, S. & Dahlgren, R. A. Temperature, water content and wet – dry cycle effects on DOC production and carbon mineralization in agricultural peat soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 38, 477–488 (2006).

Gómez-Gener, L. et al. When Water Vanishes: Magnitude and Regulation of Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Dry Temporary Streams. Ecosystems 19, 710–723 (2016).

Looman, A., Maher, D. T., Pendall, E., Bass, A. M. & Santos, I. R. The carbon dioxide evasion cycle of an intermittent first-order stream: contrasting water – air and soil – air exchange. Biogeochemistry 1–2, 87–102 (2017).

Leopold, L. B. & Wolman, M. G. River channel patterns: braided, meandering, and straight. (US Government Printing Office, 1957).

Leopold, L. B., Wolman, M. G. & Miller, J. P. Fluvial processes in geomorphology. (Courier Corporation, 2012).

Keller, E. A. & Melhorn, W. N. Rhythmic spacing and origin of pools and riffles. 723–730 (1978).

Whittaker, J. G. Sediment transport in step-pool streams. Sediment Transport in Gravel-Bed Rivers. (1987).

Grant, G. E., Swanson, F. J. & Wolman, M. G. Pattern and origin of stepped-bed morphology in high-gradient streams, Western Cascades, Oregon. (Geological Society of America, 1990).

Cardenas, M. B. & Wilson, J. L. Effects of current – bed form induced fluid flow on the thermal regime of sediments. Water Resour. Res. 43 (2007).

Munz, M., Oswald, S. E. & Schmidt, C. Analysis of riverbed temperatures to determine the geometry of subsurface water flow around in-stream geomorphological structures. J. Hydrol. 539, 74–87 (2016).

Lorke, A. et al. Technical note: drifting versus anchored flux chambers for measuring greenhouse gas emissions from running waters. Biogeosciences 12, 7013–7024 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study received funding from the European Union (INTERFACES, Seventh Framework Program, 607150) to TJB and from the Austrian Science Foundation (Y420-B17) to TJB. We thank G. Steniczka, H. Kraill, S. Schmid, C. Preiler, M. Mayr, R. Niederdorfer, C. Fasching and M. Vanek for assistance in the field and laboratory and the Zentralanstalt für Meteorologie und Geodynamik, Austria (ZAMG) for climatic data and R. Poeppl and B. Groiss for assistance in conducting field topographical surveys and providing equipment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.J.B., K.S.B. and J.S. developed the study design; K.S.B. conducted fieldwork and data analyses; N.T. and C.S. contributed to data analyses; T.J.B. and K.S.B. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boodoo, K.S., Trauth, N., Schmidt, C. et al. Gravel bars are sites of increased CO2 outgassing in stream corridors. Sci Rep 7, 14401 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14439-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14439-0

This article is cited by

-

A gas-flow funnel system to quantify advective gas emission rates from the subsurface

Environmental Earth Sciences (2022)

-

CO2 evasion along streams driven by groundwater inputs and geomorphic controls

Nature Geoscience (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.