Abstract

We used temperature-dependent x-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) measurements to examine the local structural properties around vanadium atoms at the V K edge from VO2 films. A direct comparison of the simultaneously-measured resistance and XAFS regarding the VO2 films showed that the thermally-driven structural transition occurred prior to the resistance transition during a heating, while this change simultaneously occured during a cooling. Extended-XAFS (EXAFS) analysis revealed significant increases of the Debye-Waller factors of the V-O and V-V pairs in the {111} direction of the R-phase VO2 that are due to the phonons of the V-V arrays along the same direction in a metallic phase. The existance of a substantial amount of structural disorder on the V-V pairs along the c-axis in both M1 and R phases indicates the structural instability of V-V arrays in the axis. The anomalous structural disorder that was observed on all atomic sites at the structural phase transition prevents the migration of the V 3d1 electrons, resulting in a Mott insulator in the M2-phase VO2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vanadium dioxide (VO2) is a typical metal-to-insulator transition (MIT) material, and it is accompanied by a first-order structural phase transition (SPT) from a monoclinic (M1) phase to a rutile (R) phase via a distorted-monoclinic(M2) phase. The MIT of VO2 is often compared with that of Ti2O3, which is known as a Mott-Hubbard MIT system with no structural transitions. VO2 have been extensively studied to understand the MIT mechanism1,2,3,4,5,6 and to develop its potential applications, including smart windows7, optical switches8, strain sensors9, and gas sensors10. Previous studies have showed that MIT in VO2 could be induced by various parameters, including thermal heating1,2,3,4,5,6, doping11,12,13, electric fields14,15,16, structural stress9,17,18,19, and photons20,21,22,23. The twist of V-O octahedra in the M1 and M2 phases and the dimerization of V-V pairs along the c-axis in the R phase, which are caused by strongly-correlated electrons, were proposed to understand the MIT in VO2 3,4,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. Along with the co-workers, however, Qazilbash demonstrated a mixed phase of insulating and metallic phases near the MIT temperature using infrared spectroscopy (IR) measurements. Recent neutron scattering studies showed a phonon contribution on the collapse of the bandgap27. Furthermore, metallic properties were observed even in the M1 phase near the MIT temperature28, even though the M2 phase was regarded as a Mott insulator. The decrease of the resistance in the M1 and M2 phases was ascribed to a percolation effect because a small portion of the metallic phase could be developed in the system. Tao et al. showed metallic properties that could be induced in the M1 phase via structural strain29, and other researchers have reported an observation of insulating properties in the R phase near the MIT temperature (Tc)17,30,31,32,33. Thus, discussion on the origin of the MIT and the Mott insulator in VO2 is still ongoing.

A direct comparison of the electrical and local structural properties of VO2 provides important information in the attainment of an understanding of the MIT in VO2. Diffraction techniques are canonical methods that are used to determine the structural properties of the crystals, and they can also be used to detect structural disorder in the Debye-Waller factor analysis. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) and scanning tunneling microscope (STM) measurements have been widely used to examine the atomic arrays in crystals. However, it has not been easily to describe the local structural properties around a specific species atom in compounds. Transmission IR spectroscopy is a macroscopic tool that is limited in its detection of the local structural properties. The x-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) analysis is a unique tool that can be used to describe the local structural properties around the atoms of a selected species; furthermore, the XAFS can be easily adapted to other measurements. Previous studies of the XAFS on VO2, V1−xCrxO2, and V1−xWxO2 reported local structural changes around the V and W atoms3,11,33,34,35. However, a direct comparison of the local structural and electric properties of the systems was not performed. For this study, simultaneous measurements of the XAFS at the V K edge and resistance from VO2 films were conducted to directly compare the structural and electrical properties. From in-situ XAFS measurements at the V K edge regarding VO2 films, the bond lengths and the Debye-Waller factors of the V-O and V-V pairs were quantitatively determined. Extended XAFS (EXAFS) revealed an anomalous increase of the Debye-Waller factors of atomic pairs in the {111} direction of the R-phase VO2.

From the direct comparison of the simultaneously measured XAFS and resistance, the following findings were observed: 1) The SPT is congruent with neither the MIT nor the pre-edge peak shift during a heating, while the three transitions occur nearly at the same temperature during a cooling. 2) Insulating properties are evident in the R phase near the SPT. 3) The bond-length changes of the six V-O pairs on a V-O octahedron are non-rigid. 4) Two of the bonds of the V-O pairs are slightly longer than the other four bonds of a V-O octahedron in the R phase. 5) Anomalous structural disorder exists on all atomic sites at the SPT. 6) The Debye-Waller factor (σ2) of the V(0)-V(2) pairs along the {111} direction is larger by approximately 1.7 times in the R phase compared with that in the M1 phase, while on the V(0)-V(1) pairs along the c-axis, it remains at a constant value in the M1 and the R phases. 7) A substantial amount of structural disorder exists on the V(0)-V(1) pairs, compared to that on the V(0)-V(2) pairs.

Results

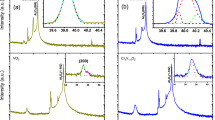

The x-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra at the V K edge demonstrated a near-absence of change in the main absorption edge, implying a constant chemical valence state of V4+ ions in the specimen, as shown in Fig. 1(a),(b). The pre-edge peaks near 5470 eV show the temperature-dependent behavior in both heating and cooling measurements, which is in sound agreement with previous studies33,34,35. The pre-edge peak mainly corresponds to a V 1 s → 3d quadrupole transition that hybridized with the V 4p orbitals, while the main edge near 5482 eV is determined by the V 4p states of VO2. The pre-edge peaks show transitions at 70 and 65 °C during heating and cooling processes, respectively. The pre-edge peaks at the transition metal K edges of the transition-metal oxides (TMOs) are mainly influenced by the 3d orbitals, the first neighboring oxygen atoms, and the second neighboring transition-metal atoms of the probing atom. The V 3d orbitals that split into the \({t}_{2g}\) and \({e}_{g}\) bands can be manifested in the pre-edge peaks at the V K edge. The details of the pre-edge peaks are discussed later and in the Supplementary Materials.

Normalized total x-ray absorption coefficient (μt) from the VO2 film at the V K edge as a function of the incident x-ray energy during (a) a heating and (b) a cooling from 40 to 100 °C. EXAFS (kχ) as functions of the photoelectron waver number, k, during (c) a heating and (d) a cooling. The EXAFS data in the range of 2.5–10.5 Å−1 were used for further analysis.

In VO2, the first and second neighboring atoms of the V atom are six O and two V atoms, respectively. The O and V atoms are located omnidirectionally and along the c-axis in the R phase, respectively, as depicted in Fig. 2(d). The atomic distances and the Debye-Waller factors (σ2, including the thermal vibration and the static disorder) of the V(0)-O and V(0)-V pairs in VO2 can be quantitatively determined by analyzing the small oscillations (EXAFS) above the absorption edge, as can be seen in Fig. 1(a),(b) 36,37. The EXAFS data in Fig. 1(c),(d) were obtained, after the atomic absorption background was determined using AUTOBK (a part of IFEFFIT)38. The local structural changes can be more obviously elucidated in the Fourier transformed EXAFS in the r-space, as shown in Fig. 2(a),(b). The peak positions corresponding to atomic distances from a V atom in VO2 are approximately 0.3 Å shorter than the true atomic positions because the photoelectron phase shift has not yet been counted. The EXAFS data in the region of 1.0–3.5 Å were fitted in the r-space to the theoretical EXAFS calculations39 with the standard fitting procedures40. The fits include only the single scattering paths of the photoelectrons because the contribution of multiple-scattering paths to the EXAFS was negligible. The structural models of the M1 (space group P21/c) and R (space group P42/mnm) phases were used to fit the EXAFS data. The atomic positions of the R phase are shown in Fig. 2(d). The EXAFS data below and above 70 °C during the heating can be fitted only with the M1- and the R-phase models, respectively. Figure 2(c) shows representative EXAFS data and the best fits for the M1 and R phases. The details of the VO2 EXAFS data fit are discussed in the Supplementary Materials and elsewhere in the literature33.

Magnitude of the Fourier transformed EXAFS as functions of the distance from a V atom during (a) a heating and (b) a cooling. For the Fourier transform, a Hanning window with a windowsill width of 1.0 Å−1 was used. (c) Representative fits of EXAFS data to the EXAFS theory. (d) The atomic positions around a core V(0) atom in the R-phase VO2.

In Fig. 3, the temperature-dependent bond lengths of the V(0)-O and V(0)-V pairs that were obtained from the best fits are compared to the simultaneously-measured resistance. The EXAFS indicates the SPT that occurred between 65 and 70 °C during the heating. The SPT temperature is in sound agreement with the previous studies3,11,28,29,30. However, the SPT temperature does not correspond to the transition temperature of the pre-edge peak of 70 °C during the heating, as shown in Fig. 1(a). During the cooling, the pre-edge peak changes at 65 °C, while the local structure around the V atoms remains in the R phase and changes to the M1 phase at 60 °C. Previous studies demonstrated that a pre-edge peak at the transition-metal K edge is sensitive to the metal-metal pairs using ab initio calculations41. The EXAFS results in Fig. 3 indicate that the distances of the V(0)-V(1) pairs at 70 and 65 °C during heating and cooling, respectively, are in a middle value of the M1 (longer distance)- and R-phase values, even though the crystalline structure corresponds to the R phase. This result suggests that the pre-edge peak shift might be more sensitive to the distance of the nearest metals (V) rather than the SPT. A direct comparison of the pre-edge peak to the EXAFS obviously reveals that the SPT is prior to and lags behind the pre-edge peak shift during the heating and cooling, respectively.

The bond lengths of one, two, and three V(0)-O pairs are approximately 1.75, 1.85, and 2.01 Å, respectively, consisting of a distorted V-O octahedron in the M1 phase. The distance of the two V(0)-V(1) pairs are approximately 2.54 and 3.03 Å in the M1 phase, respectively. The distances of the V(0)-O and V(0)-V(1) pairs in the M1 phase are quite similar to those of previous reports3,25,26,33. The bond lengths of the six V(0)-O pairs cannot be fitted with a single-bond-length variable, strongly implying that the changes in the bond length are non-rigid. The non-rigid behavior of the V-O octahedra is in sharp contrast to the previous suggestions3,25,26. The M2 phase was proposed with a model of a half of the V(0)-V(1) pairs that are tilted and the rest are parallel-aligned along the c-axis of the R phase17,25,26; therefore, the bond lengths of the six V(0)-O pairs in the M2 phase are somewhat different from those in the M1 phase25,26. However, the EXAFS cannot distinguish the M2 phase from the M1 phase due to its resolution limit. In the R phase, the bond length of the two V(0)-O pairs is longer by ~0.06 Å compared with that of the four V(0)-O pairs in the V-O octahedron, as shown in Fig. 3(a),(c). The slightly-longer bond length of the apical O atoms in the TMO octahedra is a typical result of the crystal-field splitting of the 3 d orbitals into lower \({t}_{2g}\,\)and higher \({e}_{g}\) bands that removes their degeneracy. The EXAFS result strongly suggests the splitting of the V 3 d orbitals into the \({t}_{2g}\) and \({e}_{g}\) bands, and the apical O atoms with a longer bond length from the central V atom of a V-O octahedron, that are crystallographically placed in a horizontal plane perpendicular to the c-axis of the R-phase VO2 25,26. The V 3d1 electrons likely lie in a lower energy level of the \({t}_{2g}\)(\({d}_{xy}\), \({d}_{xz}\)) band in the VO2, as illustrated in Fig. 4(e). The temperature-dependent atomic distances reveal the SPT temperatures differing from the Tcs of the MIT during both heating and cooling. In the R phase near the SPT, the resistance shows that VO2 still remains in an insulating phase.

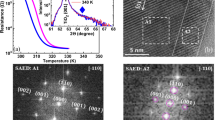

The temperature-dependent σ2s of the (a) V(0)-O, (b) the V(0)-V(1), and (c) the V(0)-V(2) pairs during (red dots) a heating and (blue squares) a cooling. (d) The temperature-dependent distance of the V(0)-V(2) pairs during a heating and a cooling. (e) and (f) The schematics of the \({{\boldsymbol{t}}}_{2{\boldsymbol{g}}}\)(\({{\boldsymbol{d}}}_{{\boldsymbol{xy}}}\), \({{\boldsymbol{d}}}_{{\boldsymbol{xz}}}\)) and d || of the V 3d orbitals of V atoms in the (110) plane of the R-phase VO2, respectively, and the light-blue arrows indicate the {111} direction of phonon propagation.

The mean Debye-Waller factors (σ2s) of the V(0)-O and V(0)-V(2) pairs as determined by the EXAFS-data fits are larger in the R phase than in the M1 phase, while, except at the SPT where the σ2 anomalously increases, they are nearly constant in the V(0)-V(1) pairs, as shown in Fig. 4. The previous studies theoretically and experimentally demonstrated that the R phase is structurally more stable than the M1 phase42. Thus, it is expected that the σ2 value of the V-V pairs will be larger in the M1 phase than in the R phase, because the zigzag pattern of the V atoms in the M1 phase can more effectively cause a static disorder in the atomic pairs, particularly the V(0)-V(2) pairs. Furthermore, an extra structural disorder is expected in the M1 phase because the R-phase VO2 films were initially synthesized at ~600 °C and cooled to the M1 phase. The thermal vibration and the static disorder, σ2(T) + σ2 static, generally contribute to the σ2 of the atomic pairs, and σ2(T) can be understood by the Einstein or the correlated Debye model40,43. The abrupt increase of the σ2 of the V(0)-O and V(0)-V(2) pairs at the SPT is unexpected because the σ2(T) due to only the thermal vibration gradually increases during the heating. An extra σ2 value in the R phase may not come from a sudden increase in the structural disorder because the VO2 in the R phase is structurally more stable than that in the M1 phase42. The constant σ2 of the V(0)-V(1) pairs in the M1 and R phases is further evidence of the lack of any extra static disorder in the R phase. The extra σ2 of the V(0)-V(2) pairs in the R phase might correspond to the phonons that were observed with the use of neutron-scattering measurements27, and the extra σ2 of the V(0)-O pairs in the R phase can also be induced by phonons in V arrays along the {111} directions, because an O atom is located near the bonding line of the V(0)-V(2) pairs, and the EXAFS measures the motion of an O atom relative to a probing V atom. The absence of a change in the σ2 values of the V(0)-V(1) pairs in the M1 and the R phases indicates the lack of any extra phonons along the c-axis, and this result is in sound agreement with those of the previous studies27.

In the M1 phase, the σ2 of the V(0)-V(1) pairs is approximately 2.8 times larger than that of the V(0)-V(2) pairs. A large σ2 value in the V(0)-V(1) pairs indicates the existance of an extra structural disorder in the pairs over the entire temperature range because extra thermal phonons have not been observed along the c-axis27. The structural disorder in the V(0)-V(1) pairs likely prevents the propagation of the V 3d1 electrons along the c-axis, because previous studies reported that the electrical resistivity of metallic-metal oxides was increased due to a structural disorder44. The extra structural disorder at the SPT might be ascribed to the M2 phase in which the V(0)-V(1) pairs are partially parallel and tilted toward the c-axis17,25,26. However, the EXAFS cannot resolve a slight offset of an atomic position due to its resolution limit. The resistance from the VO2 films shows Tcs values of ~73.8 and ~65.0 °C during the heating and cooling, respectively, as shown in Fig. 3. The heating Tc lags behind the SPT, while the cooling Tc is prior to the SPT. Based on a strongly-correlated-electron model25,26, it was expected that the resistance of the VO2 film would be considerably decreased in the R phase. However, in the R phase, the resistance decreases only slightly at 70 °C during the heating, and it increased at 65 °C during the cooling. The resistance in the R phase can be ascribed to a structural disorder. The anomalous structural disorders on all atomic sites at the SPT, as shown in Fig. 4, can effectively block the migration of the V 3d1 electrons, resulting in an inconsistency of the Tc and the SPT.

Discussion

The metallic electrons are the V 3d1 electrons of VO2. The pre-edge peaks of the XANES at the V K edge reflect the local density of states (LDOS) of the V 3d orbitals. As mentioned above, the temperature-dependent behavior of the pre-edge peaks does not match with those of the SPT, as shown in Figs 1 and 3. The XANES was fitted to an arctangent-Gaussian model in which the pre-edge peaks are fitted with two Gaussian functions, as shown in Fig. 5 (a). Figure 5(b)–(d) demonstrate the relative position (∆E, Emain edge − Epre-edge peak), intensity, and FWHM (full-width at half maximum) of the first pre-edge peak(peak 1) at ~5469 eV that were obtained from the best fits, respectively. Emain edge of ~5482 eV is mainly determined by the V 4p states. The temperature-dependent behavior of the second pre-edge peak(peak 2) at ~5471 eV is discussed in the Supplementary Materials in detail. The ΔE change of ~0.5 eV before and after the transition temperatures is in sound agreement with the binding-energy change of the V 3d electron between the M1 and the R phases45. The separation of the pre-edge peaks corresponds to an energy gap between the \({t}_{2g}\) and \({e}_{g}\) bands25,26 that is reflected by the elongation of the apical oxygen distance in the V(0)-O octahedron, as determined by the EXAFS analysis. The measured separation of the pre-edge peaks of 2.0 ± 0.3 eV roughly agrees with the FEFF9 calculations (see Supplementary Materials) of ~2.8 eV and the band calculations of ~3.0 eV26. The pre-edge peaks imply that the Fermi level of VO2 lies within the first pre-edge peak as the result of only one electron in the V 3d orbitals.

(a) XANES from the VO2 film at the V K edge and best fit with an arctangent-Gaussian model. (b) The relative position (ΔE) of the pre-edge peak (peak 1) to the main absorption edge, (c) the intensity, and (d) the FWHM of the first pre-edge peak with (black dots) simultaneously-measured resistance during (red dots) a heating and (blue squares) a cooling.

The area of the pre-edge peaks is directly proportional to the local empty density of the states of the V 3d orbitals because the XANES detects the empty states near the Fermi level. The pre-edge peak becomes weaker and broader above the transition temperature, as shown in Fig. 5(c),(d). The intensity and the FWHM of the peak do not coincide with either the MIT or the SPT, and for the first pre-edge peak, it might be expected that it will become narrow when two bands in the M1 phase merge into a single band in the R phase. However, the peak broadens in the R phase compared to that in the M1 phase. These results strongly suggest that the changes of the LDOS of the V 3d orbitals are not directly proportional to the MIT. The area change of the first pre-edge peak that is obtained from the intensity and the FWHM of the peak cannot be precisely resolved due to a large fitting uncertainty. The transition temperatures of the resistance, the structure, and the pre-edge peak are summarized in Table 1. The pre-edge transition follows the SPT, and then the resistance changes during the heating, but these shifts occured nearly simultaneously during the cooling. The anomalous structural disorder that was observed near the MIT can play a critical role in the non-congruent transitions of the resistance, structure, and pre-edge peaks.

Theoretical calculations for which a dynamical mean-field theory (DMFT) was used demonstrated that the band gap in the M1 phase disappeared in the R phase4. However, other researchers have argued that the M2 phase that is evident near SPT is a Mott-Hubbard insulator17,42,45. Mott proposed impurity levels that collapse the bandgap in Ti2O3 above Tc 46. Hwang et al. demonstrated that an extra disorder in the Ti-Ti pairs in Ti2O3 plays an important role in the MIT47. The theoretical works did not include the structural disorder, the local distortion, and a non-rigid change in VO2 structure, particularly near the SPT4,17,25,26. This study elucidates that the insulating properties of the M2-phase VO2 are directly related to an anomalous structural disorder, particularly at the V sites. The significant influence of a structural disorder on the strongly-correlated electrons has been reported using various systems, including MIT materials46,47, superconductors48,49,50, Kondo effects51, and copolymers52. A direct comparison of the resistance and the XAFS measurements reveals that the insulating properties in the R-phase VO2 mainly originate from a structural disorder, while the metallic properties in the M1-phase VO2 could be ascribed to a percolation effect2 and a distortion of the V 3d orbitals29. A large amount of structural disorder on the V(1) sites in both the M1 and R phases indicates structural instabilities that can prevent phonon propagation and the V 3 d1 electron migration along the c-axis in the R phase.

The elongation of the apical O distance of the V(0)-O octahedron in the R-phase VO2 is evidence that the V 3 d1 electrons lie in the lower \({t}_{2g}\) band near the {111} direction (\({d}_{xy}\) and \({d}_{xz}\) orbitals) of the R phase, as illustrated in Fig. 4(e). The V 3d1 electrons in the lower energy band of the \({d}_{xy}\) and \({d}_{xz}\) orbitals can jump to the higher energy band of the \({d}_{||}({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}})\) orbital via a coupling with the phonons22, as illustrated in Fig. 4(f). The jump from the \({d}_{xy}\) and \({d}_{xz}\) orbitals to the \({d}_{\parallel }\) orbital was observed using photoinduced MIT measurements22,23. This can not only build a conduction channel along the c-axis, as depicted in Fig. 4(f), but, as illustrated in Fig. 4(e). the V 3d1 electrons can also jump to the next V atoms along the {111} direction with the mediation of the phonon in the same direction. For the latter case, the conduction electrons may migrate with a zigzag pattern along an external electric field direction; V(0) → V(2) → V(1) for an example of the external field in the c-axis. For the conduction electrons, a competitiveness between the (001)- and {111}-direction jumps can occure, because a considerable structural disorder is evident in the V(0)-V(1) pairs and the V(0)-V(2) distance is ~0.6 Å longer than the V(0)-V(1) distance in the R phase, as shown in Fig. 3 and 4. Thus, two-way (V(0)-V(1) dimerization along the c-axis and zigzag pattern) and one-way (zigzag pattern) channels can be main routes for the conduction electrons that migrate along the external electric field parallel and perpendicular to the c-axis, respectively. This scenario corresponds to the anisotropy conductivity of VO2, where higher and lower conductivity are parallel and perpendicular to the c-axis, respectively14,24,53. This study strongly suggests that the phonons in the {111} direction of the R-phase VO2 play a key role in the delocalization of the V 3d1 electrons, and that the structural disorder, particularly at V sites, prevents the propagation of electrons as well as phonons near the SPT temperature.

The position of the V atoms has a zigzag pattern in the M1- and M2-phase VO2. The zigzag pattern can not only suppress the degeneracy of the V 3d orbitals, but it can also spread the V 3d1 electrons onmidirectionally. In the M1-phaseVO2, the chance that the V 3d1 electrons can jump to the next V atoms is very slight due to the bandgap and the random direction of the orbitals. Pouget et al. reported that stress in the (110) direction of the R-phase VO2 affected the structural and electrical transitions more than that in the (001) direction18, suggesting the distorted-omnidirectional orbitals of the zigzag-patterned V atoms, thereby preventing the migration of the V 3d1 electrons22,23. When the crystals are released from the zigzag pattern, the V 3d orbitals are directionally aligned and the phonons can propagate along the {111} direction, reducing the total entropy27. On the condition that the V 3d orbitals are aligned in a certain direction, the vibration of the V atoms assists the delocalization of the V 3d1 electrons. In this scenario, the tetragonal symmetry in VO2 is a sufficient condition for its MIT. A static charge alignment along a certain crystalline direction in a tetragonal symmetry has been observed in various systems, including a static strip phase in La2-x-ySrxNdyCuO4 54, polar tetragonal symmetry in BaTiO3 55 and checkerboard phase in Ca2-xNaxCuO2Cl2 56. The results of the present study strongly suggest that a parameter deriving a tetragonal symmetry in VO2 can induce its MIT without a bandgap change.

Conclusion

Using the temperature-dependent XAFS measurements with simultaneously-measured resistance, it has been demonstrated that the SPT, the LDOS change of the V 3d orbitals, and the MIT do not occur at the same temperature during a heating, while the MIT nearly coincides with the SPT and LDOS change during a cooling. An anomalous structural disorder, particularly at V sites, effectively affects the migration of the metallic electrons, resulting in the Mott insulating properties in the M2 phase and the non-congruence of the SPT, MIT, and LDOS. The EXAFS measurements revealed a longer distance of the apical-O atoms of a V-O octahedron in the R-phase VO2, indicating the likely placement of the V 3d1 electron in the \({t}_{2g}\) band. With a tetragonal symmetry (R phase) to lower the entropy of VO2 at higher temperatures27, the phonons can propagate in V-atom arrays along the {111} direction. In the M1 phase, the V atoms are slightly offset from a diagonal line, so that phonon propagation is blocked. A large amount of structural disorder in the V(0)-V(1) pairs along the c-axis effectively prevents the phonon propagation. The thermally-induced phonons in the {111} direction assist the delocalization of the V 3d1 electrons in the R phase VO2 and the electrons likely migrate via the V-V array in the {111} direction as well as the V-V dimerization along the c-axis. This study clarifies that the tetragonal symmetry is essentially important for the metallic phase in VO2.

Methods

Synthesis of VO2 films

The b-oriented VO2 films were synthesized on α-Al2O3(0001) substrates via DC-magnetron-sputtering deposition. A vanadium target (purity: 99.9%) was used. The base and working presses of the sputtering chamber were ~10–6 and ~10−3 Torr under an Ar atmosphere, respectively. The substrate temperature was maintained at ~500 °C with a sputtering power of ~30 W. The films were annealed at ~500 °C for ~30 minutes under a mixture gas flow of Ar and O2 with an Ar: O2 flow ratio of ~5: 1. The synthesis of VO2 films was described elsewhere in detail33.

Characterization

The b-oriented VO2 films with a lattice constant b of 4.785 Å were evaluated using x-ray diffraction measurements with conventional tube x-rays with Cu Kα radiation in air at room temperature. The mean grain size of ~2 μm and thickness of ~0.10 μm of the films were observed via field-emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM, S-5500, Hitachi).

XAFS measurements and analysis

XAFS measurements were performed from VO2 films at the V K edge (5465 eV) by selecting the incident x-ray energy with a three-quarters tuned Si(111) double crystal monochromator at the 8 C beamline of the Pohang Light Source (PLS) during the heating and cooling in the temperature range of 40–100 °C. In the fluorescence mode at the incident x-ray angle of 45° to the film surface, the XAFS measurements of the VO2 films were simultaneously carried out with resistance measurements by using a home-made in-situ cell to directly compare the results of these two sets of measurements. At least three XAFS scans were taken at each temperature to exclude any unexpected error during the measurements. The temperature of the specimen during the XAFS scans was precisely monitored and controlled within an error of ± 0.1 °C, and the self-absorption of the films with a thickness of ~0.10 μm is negligible because the one-absorption length of VO2 at the V K edge is ~6.5 μm. The XAFS data were analyzed using the IFEFFIT package38 and standard EXAFS fitting procedures40. The theoretical calculations of EXAFS and LDOS were obtained using the FEFF9 code39.

DC resistance measurements

The DC resistance of the VO2 films was measured by using a two-probe system at an applied voltage of 0.5 V in the home-made in-situ cell. The XAFS and the resistance measurements were performed after the system temperature stabilized because the resistivity of the films showed a time-dependent behavior just after being heated or cooled33.

References

Morin, F. J. Oxides which show a metal-to-insulator transition at the Neel temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 3, 34–36 (1959).

Qazilbash, M. M. et al. Mott transition in VO2 revealed by infrared spectroscopy and nano-imaging. Science 318, 1750–1753 (2007).

Yao, T. et al. Understanding the Nature of the Kinetic Process in a VO2 Metal-Insulator Transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 226405 (2010).

Bierman, S. et al. Dynamical Singlets and Correlation-Assisted Peierls Transition in VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 026404 (2005).

Mossanek, R. J. O. et al. Evolution of the d|| band across the metal-insulator transition in VO2. Solid State Comm. 135, 189 (2005).

Popuri, S. R. et al. VO2 (A): Reinvestigation of crystal structure, phase transition and crystal growth mechanisms. J. Solid State Chem. 213, 79 (2014).

Zhou, J. VO2 thermochromic smart window for energy savings and generation. Scientific Report 3, 3029 (2013).

Chen, X. et al. Thermoelectrical and optical characteristics research on novel nanostructured VO2 thin film. Optik 124, 2041 (2013).

Guo, H. et al. Mechanics and Dynamics of the Strain-Induced M1-M2 Structural Phase Transition in Individual VO2 nanowires. Nano Lett. 11, 3207 (2010).

Strelcov, E. et al. Gas Sensor Based on Metal-Insulator Transition in VO2 Nanowire Thermistor. Nano Lett. 9, 2322 (2009).

Tan, X. et al. Unraveling Metal-insulator Transition Mechanism of VO2 Triggered by Tungsten Doping. Scientific Reports 2, 466 (2012).

Holman, K. L. et al. Insulator to correlated metal transition in V1−xMoxO2. Phys. Rev. B 79, 245114 (2009).

Marini, C. et al. Optical properties of V1−xCrxO2 compounds under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 77, 235111 (2008).

Jeong, J.-W. et al. Suppression of Metal-Insulator Transition in VO2 by Electric Field–Induced Oxygen Vacancy Formation. Science 339, 1402 (2013).

Stefanovich, G. et al. Electrical switching and Mott transition in VO2. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 12, 8837 (2000).

Liu, M. et al. Terahertz-field-induced insulator-to-metal transition in vanadium dioxide metamaterial. Nature 497, 345 (2012).

Sohn, J.-I. et al. Surface-Stress-Induced Mott Transition and Nature of Associated Spatial Phase Transition in Single Crystalline VO2 Nanowires. Nano Lett. 9, 3392 (2009).

Pouget, J. P. et al. Electron Localization Induced by Uniaxial Stress in Pure VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 35, 873 (1975).

Cao, J. et al. Colossal thermal-mechanical actuation via phase transition in single-crystal VO2 microcantilevers. J. Appl. Phys. 108, 083538 (2010).

Cavalleri, A. et al. Band-Selective Measurements of Electron Dynamics in VO2 Using Femtosecond Near-Edge X-Ray Absorption. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 067405 (2005).

Ku¨bler, C. et al. Coherent Structural Dynamics and Electronic Correlations during an Ultrafast Insulator-to-Metal Phase Transition in VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 116401 (2007).

Morrison, V. R. et al. A photoinduced metal-like phase of monoclinic VO2 revealed by ultrafast electron diffraction. Science 346, 445 (2014).

Tao, Z. et al. The nature of photoinduced phase transition and metastable states in vanadium dioxide. Scientific Report 6, 38514 (2016).

Kittiwatanakul, S. et al. Transport Anisotropy of Epitaxial VO2 Films near the Metal–Semiconductor Transition. Appl. Phys. Exp. 4, 091104 (2011).

Goodenough, J. B. The Two Components of the Crystallographic Transition in VO2. J. Solid State Chem. 3, 490 (1971).

Eyert, V. The metal-insulator transitions of VO2: A band theoretical approach. Ann. Phys. (Leipzig) 11, 650 (2002).

Budai, J. B. et al. Metallization of vanadium dioxide driven by large phonon entropy. Nature 515, 535 (2014).

Muraoka, Y. et al. Metal–insulator transition of VO2 thin films grown on TiO2 (001) and (110) substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 583 (2002).

Tao, Z. et al. Decoupling of Structural and Electronic Phase Transitions in VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 166406 (2012).

Zhang, S. et al. Direct Correlation of Structural Domain Formation with the Metal Insulator Transition in a VO2 Nanobeam. Nano Lett. 9, 4527 (2009).

Haverkort, M. W. et al. Orbital-Assisted Metal-Insulator Transition in VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 196404 (2005).

Hongwei, L. et al. Size effects on metal-insulator phase transition in individual vanadium dioxide nanowires. Optics Express 22, 30748 (2014).

Jin, Z. et al. Synthesis and temperature-dependent local structural and electrical properties of VO2 films. Current. Appl. Phys. 16, 183 (2016).

Wu, Y. et al. Depressed transition temperature of WxV1−xO2: mechanistic insights from the X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 17705 (2014).

Marini, C. et al. Tracking competitive lattice distortions in strongly correlated VO2-based systems: A temperature-dependent EXAFS study. EPL 102, 66004 (2013).

Sayers, D. E. et al. New Technique for Investigating Noncrystalline Structures: Fourier Analysis of the Extended X-Ray—Absorption Fine Structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 27, 1204 (1971).

Rehr, J. J. et al. Theoretical approaches to x-ray absorption fine structure. Rev. Mod. Phys. 72, 621 (2000).

Newville, M. IFEFFIT: interactive XAFS analysis and FEFF fitting. J. Synchrotron Rad. 8, 322 (2001).

Rehr, J. J. et al. Parameter-free calculations of X-ray spectra with FEFF9. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 5503 (2010).

Han, S.-W. et al. Local structure in the stripe phase of La1.6-xSrxNd0.4CuO4. Phys. Rev. B 66, 094101 (2002).

Seo, S.-Y. et al. X-ray absorption fine structure study of cobalt ion distribution in ferromagnetic Zn1−xCoxO films. J. Phys. Cond. Matter 25, 256005 (2013).

Leroux, Ch. VO2(B) to VO2(R): Theoretical structures of VO2 polymorphs and in situ electron microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 57, 5111 (1998).

Beni, G. et al. Temperature and polarization dependence of extended x-ray absorption fine-structure spectra. Phys. Rev. B 14, 1514 (1976).

Lin, Y. F. et al. Nanocontact resistance and structural disorder induced resistivity variation in metallic metal-oxide nanowires. Nanotechnology 20, 455401 (2009).

Koethe, T. C. et al. Transfer of Spectral Weight and Symmetry across the Metal-Insulator Transition in VO2. Phy. Rev. Lett. 97, 116402 (2006).

Hwang, I.-H. et al. Anomalous structural disorder and distortion in metal-to-insulator-transition Ti2O3. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 014905 (2016).

Lu, J. Order–disorder transition in a two-dimensional boron–carbon–nitride alloy. Nat. Commun. 4, 2681 (2013).

Seo, S. et al. Disorder in quantum critical superconductors. Nat. Phys. 10, 120 (2014).

Mishra, V. Effect of disorder on superconductivity in the presence of spin-density wave order. Phys. Rev. B 91, 104501 (2015).

Daniel, M. et al. Perturbing the Superconducting Planes in CeCoIn5 by Sn Substitution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 016406 (2005).

Han, S.-W. et al. Disorder-induced Kondo behavior in nanostructured CeAl2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 097204 (2006).

Khandpur, A. K. et al. Polyisoprene-Polystyrene Diblock Copolymer Phase Diagram near the Order-Disorder Transition. Macromolecules 28, 8796 (1995).

Bongers, P. F. Anisotropy of the electrical conductivity of VO2 single crystals. Solid State Comm. 3, 275 (1965).

Tranquada, J. M. et al. Evidence for stripe correlations of spins and holes in copper oxide superconductors. Nature (London) 375, 561 (1995).

Ren, X. Large electric-field-induced strain in ferroelectric crystals by point-defect-mediated reversible domain switching. Nature Mater. 3, 91 (2004).

Hanaguri et al. T. A ‘checkerboard’ electronic crystal state in lightly hole-doped Ca2−xNaxCuO2Cl2C. Nature 430, 1001 (2004).

Acknowledgements

The work was conducted under the auspices of the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea government (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT and Future Planning (MSIP) (No. 2017K1A3A7A09016390 and No. 2016R1D1A3B03931824). The XAFS data were collected at the 8 C beamline of Pohang Light Source.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.H.H., Z.J., C.I.P., and S.W.H. performed the in-situ XAFS and resistance measurements. Z.J. and C.I.P. performed the synthesis, XRD, SEM measurements and characterization of VO2 films. I.H.H. and S.W.H. designed the in-situ cell and performed XAFS data analysis. S.W.H. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hwang, IH., Jin, Z., Park, CI. et al. The influence of structural disorder and phonon on metal-to-insulator transition of VO 2 . Sci Rep 7, 14802 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14235-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14235-w

This article is cited by

-

Probing the role of thermal vibrational disorder in the SPT of VO\(_2\) by Raman spectroscopy

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Decoupling the metal insulator transition and crystal field effects of VO2

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.