Abstract

The high-throughput analysis of satellite DNA (satDNA) content, by means of Illumina sequencing, unveiled 45 satDNA families in the genome of Astyanax paranae, with repeat unit length (RUL) ranging from 6 to 365 bp and marked predominance of short satellites (median length = 59 bp). The analysis of chromosomal location of 35 satDNAs in A. paranae, A. fasciatus and A. bockmanni revealed that most satellites are shared between the three species and show highly similar patterns of chromosome distribution. The high similarity in satellite DNA content between these species is most likely due to their recent common descent. Among the few differences found, the ApaSat44-21 satellite was present only on the B chromosome of A. paranae, but not on the A or B chromosomes of the two other species. Likewise, the ApaSat20-18 satellite was B-specific in A. paranae but was however present on A and B chromosomes of A. fasciatus and A. bockmanni. The isochromosome nature of B chromosomes in these species was evidenced by the symmetric location of many satDNAs on both B chromosome arms, and the lower symmetry observed in the A. fasciatus BfMa chromosome suggests that it is older than those analyzed in A. paranae and A. bockmanni.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Satellite DNA consists of arrays of tandemly repeated units of two or more nucleotides usually clustered in the heterochromatic regions of chromosomes, but also found on euchromatic regions1,2. The birth of a satDNA implies the de novo duplication of a DNA sequence in a specific genomic site, subsequent amplification and dissemination throughout the genome, and local massive amplification yielding clusters being cytologically visible2. According to the library hypothesis3, related organisms share a common library of satellite DNA sequences and, in each species, certain variants may be amplified, generating differential collections of visible satellites in closely related species. It implies that the appearance of a “new” satDNA usually represents the amplification of one of the satellites already present at low level in the library. Moreover, Fry and Salser3 suggested that the acquisition of a biological function might be responsible for the maintenance of a satellite sequence in the library over long evolutionary periods. In fact, some satDNAs play important genomic roles, such as telomere and centromere formation and function4,5, and new functions have recently been attributed to some satellite DNAs1. On the other hand, other satellites remain as genomic “junk” if they do not have an immediate use but may occasionally acquire one (for review see Garrido-Ramos6).

Most current satDNAs were uncovered through the ladder pattern yielded by restriction enzyme digestion followed by gel electrophoresis, although this technique shows limitations7,8. The advent of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) and the emergence of bioinformatics tools, such as RepeatExplorer9, have greatly facilitated satDNA discovery, and a new toolkit based on the former software has uncovered unsuspected levels of intragenomic diversity in satDNA content2. For instance, these latter authors unveiled 62 satDNA families in the genome of the migratory locust, a species where the conventional restriction-electrophoresis protocol had failed to find any satDNA. This impelled these authors to suggest the term satellitome for the whole collection of satDNA families found in a single genome, and they suggested that the high-throughput analysis of the satellitome might illuminate many aspects of satDNA evolution2.

Satellite DNA has been profusely studied in plants and animals7,10,11,12. In contrast, satDNA has scarcely been reported in fish, with only a few exceptions13,14,15,16,17,18,19. In all cases, no more than seven satellite DNAs were described for a given species19.

Among the Neotropical ichthyofauna, the genus Astyanax (Baird & Girard) is one of the most species-rich group. It is currently composed of 244 species20 characterized by wide genome plasticity, with diploid numbers ranging from 2n = 36 in A. shubarti to 2n = 50 in several species21,22 and the occurrence of variation in karyotype formulas, B chromosome presence, differential distribution of repetitive DNA and heterochromatin and hybrid cytotypes23. The high number of species makes this genus an excellent material for testing the satDNA library hypothesis3.

Several repetitive DNAs have been physically mapped in Astyanax, including ribosomal DNA, U snRNA genes, histone genes, transposable elements and microsatellites24,25,26. However, only one satDNA has been described in this genus, namely the As51 satDNA found in A. scabripinnis by digestion with the KpnI restriction enzyme15. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) mapping showed its location in non-centromeric heterochromatin, i.e., close to telomeric regions of the long arm of some acrocentric chromosomes, in the nucleolus organizer region and in the interstitial heterochromatin of chromosome 2415. In the B chromosome of this species, the As51 satDNA was found to be largely symmetrically on both arms, which suggested its isochromosome nature15. Later, several studies have reported the presence of the As51 satDNA on A chromosomes of other Astyanax species, but it was only detected in the B chromosome of A. fasciatus, in addition to those of A. scabripinnis (for a review, see Silva et al.23).

Here, we perform a high-throughput analysis of satDNA content in Astyanax paranae, by means of Illumina sequencing of 0B and 1B genomes, using RepeatExplorer9 and the satMiner toolkit recently developed by Ruiz-Ruano et al.2. This uncovered the presence of 45 satDNA families, 35 of which were PCR amplified on genomic DNA (gDNA) from this species to generate DNA probes for each satDNA. We then performed FISH analysis in A. paranae and two other species also carrying B chromosomes (A. fasciatus and A. bockmanni). These results have greatly increased the current knowledge on satellite DNA in Astyanax and provided new insights on B chromosome evolution.

Results

The satellitome in A. paranae

After nine iterations of the satMiner toolkit protocol (until no additional satDNA was uncovered), we found 45 different satDNA families (67 variants), with repeat unit lengths (RUL) ranging between 6 and 365 bp, and 59 bp median value (Table 1). Length distribution was thus clearly biased due to a predominance of short satellites, as more than half (33) showed RUL shorter than 100 bp (Supplementary Fig. S1). The A + T content of the consensus satDNA sequences varied between 30.3% and 75.1% among families, with 55.8% median value, indicating a slight bias towards A + T rich satellites. The Shapiro-Wilks test showed that A + T content was the only satellitome feature fitting a normal distribution (W = 0.978, P = 0.55), the remaining variables (RUL, abundance and divergence) being far from normality (P < 0.05 in all cases). For this reason, we used non-parametric tests for subsequent analysis.

Spearman rank correlation analysis showed that RUL in the 45 satellite DNA families showed a positive correlation with the A + T content (rS = 0.34, t = 2.34, P = 0.024), indicating that longer satellites tend to be richer in A + T. However, these two parameters failed to show a significant correlation with abundance or divergence in the 0B and 1B genomes (P > 0.05 in all cases).

Sequence comparison between repeat unit sequences of the 45 satDNA families detected homology only between ApaSat02-236 and ApaSat04-233 (78.8%), with a single variant each, and these two families were grouped into superfamily 1 (SF1). Remarkably, these two satDNAs show closely similar RUL, suggesting that the high divergence showed by both families (15% and 17%, respectively) was mostly due to nucleotide substitutions, whereas indels were small and rare (Supplementary Fig. S2).

We tried to infer bioinformatically the presence of satDNA families in A. paranae B chromosomes, through their possible changes in abundance between 0B and 1B gDNA libraries. This revealed that 18 satDNA families showed positive values for log2 A1B/A0B, suggesting that they might be abundant in the B chromosome (Table 1). The remaining 27 satDNAs, however, showed negative values for this parameter, thus suggesting that their abundance might be lower in B than A chromosomes. Bearing in mind that the length of the metacentric B chromosome in A. paranae (BpM) represents approximately 8% of the total length of the haploid A chromosome set (Silva et al. unpublished), we estimate that, in case of complete absence of a given satDNA in the B chromosome, the maximum decrease in satDNA abundance, expected in a 1B genome, would be about 4%. However, 22 of these 27 satDNAs showed abundance decrease surpassing this threshold, suggesting that satDNA absence in the B chromosome does not explain the observed differences in satDNA abundance between the 0B and 1B individuals. We thus believe that these differences are most likely due to between-individual differences in satDNA abundance in A and/or B chromosomes. In fact, only 8 out of the 18 satDNAs showing higher abundance in the 1B genome were actually visualized by FISH on the B chromosome (see below). All these results indicate the convenience of separately sequencing several B-carrying and B-lacking individuals to lessen the effect of A chromosome variation.

Chromosome distribution of 35 satellite DNA families in A. paranae

We designed primers for PCR amplification of all 45 satDNAs found, but only 35 of them worked successfully on A. paranae gDNA. Given that this represents a huge collection of satDNAs for FISH analysis, we did not try to redesign additional primers for the 10 satDNAs whose PCR amplification had failed in the first try.

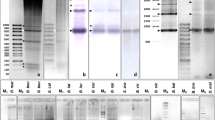

Out of the 35 satellite families analyzed by FISH, 30 showed conspicuous clusters in at least one chromosome (c pattern) and 5 failed to yield a FISH signal, so we consider that they are non-clustered at cytological level (nc pattern) (Fig. 1). Clustered satDNAs were found in both heterochromatic and euchromatic regions (Supplementary Fig. S3). RUL values of clustered (median = 77.5) and non-clustered (median = 21) satellites showed similarly high variances (6448.3 and 1423.5, respectively) (Levene’s test: F = 2.5, df = 1, 33, P = 0.124) and the Mann-Whitney test showed that clustered satellites show significantly longer repeat units (U = 26, P = 0.021) (Fig. 2).

Examples of the chromosome distribution patterns of the SatDNAs found in A. paranae: non-clustered (a) and clustered (b). Each cell is shown with satDNA FISH (red) merged with DAPI (upper panel) and with satDNA FISH (lower panel). Note that the ApaSat36-21 does not show any FISH signal (non-clustered pattern). Bar = 10 μm.

Comparison of satellite distribution in two other Astyanax species

FISH analysis of the same 35 satellites in A. fasciatus and A. bockmanni showed the presence of clusters for 21 and 27 families, respectively (Table 2). We found generally good consistency between species for distribution patterns on A chromosomes, with 17 satellite families showing the same pattern in the three species and 10 showing the same pattern in two species. In this latter case, the absence of clusters in the third species could be due to satellite absence or else to its presence in a non-clustered pattern. These two possibilities could be tested by a detailed satellitome analysis in A. fasciatus and A. bockmanni. For this reason, we limited our observations to scoring how many satellites, out of the 35 analyzed in A. paranae, were clustered (c pattern) in A. fasciatus and A. bockmanni, as inferred from FISH analysis. In fact, 26 out of the 30 satDNA families which showed FISH signals on A. paranae chromosomes (c pattern) also showed signals on one or the two other Astyanax species. The four remaining satellites showed FISH signals in A. paranae but not in the two other species. This does not necessarily mean that these satellites are absent from the satDNA library in these two species, as they may be present but in a non-clustered pattern. The reverse situation was found for ApaSat20-18 and ApaSat36-21, as they were not visualized by FISH on A. paranae A chromosomes even though they were bioinformatically detected in the 0B genome (nc pattern), but the former satellite showed conspicuous FISH signals on A chromosomes of A. fasciatus and A. bockmanni (Fig. 3) whereas the latter showed them on those of A. bockmanni only (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S4).

Both members of the SF1 superfamily (i.e., ApaSat02-236 and ApaSat04-233) showed the same chromosomal location on the pericentromeric region of many A chromosomes in the three species analyzed (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. S5).

Two satDNAs (ApaSat20-18 and ApaSat44-21) showed conspicuous clusters on B chromosomes but did not show a FISH signal on A chromosomes (Table 1), thus appearing to be B-specific in the A. paranae genome. However, they were detected bioinformatically in the 0B genome, although at very low abundance (0.033 and 0.002%, respectively) (Table 1). Both satDNAs show short RUL, but only ApaSat44-21 appears to be exclusive to the A. paranae 1B genome, as it was not detected in A. fasciatus or A. bockmanni chromosomes (Supplementary Fig. S6), whereas ApaSat20-18 is clustered in the A and B chromosomes of A. fasciatus and A. bockmanni (Supplementary Fig. 3a), indicating that this satellite might have originated in one of these two species and was transferred between species, perhaps with the B chromosome. It would thus be interesting to perform a detailed analysis of sequence variation for this satellite in A and B chromosomes of the three species to investigate if it arose in A or B chromosomes.

Satellite distribution on B chromosomes showed a very high tendency toward symmetric location with respect to the centromere for those satellites showing non-centromeric location (Fig. 5). Assigning the value 1 to a symmetric pattern and 0 to a non-symmetric one, we calculated a symmetry index (SI) for each B chromosome as the average symmetry for all non-centromeric satellites found on it (Table 3). This showed that BpM and BbM were highly symmetric (SI = 1) and BfMa was poorly symmetric (SI = 0.45).

Distribution of satDNAs on the B chromosomes of A. paranae (BpM), A. fasciatus (BfMa) and A. bockmanni (BbM). The red numbers indicate catalog number for each satDNA. DAPI-stained chromosomes and satDNA hybridization patterns are displayed side-by-side for each B-variant. Note that all satDNAs showing signals on BpM and BbM chromosomes show symmetric distribution, whereas only five of them are symmetric in the BfMa chromosome.

Finally, out of the 30 satellite DNA families which showed a clustered pattern at cytological level, i.e. visible by FISH, in A. paranae, 26 were shared by the A chromosomes of one or the two other Astyanax species analysed here. In the case of B chromosomes, a total of 18 satellites were visualized on the B chromosomes of these three species, and only 12 were shared by Bs in two or three species, in high resemblance with the case of A chromosomes (Fisher exact test: P = 0.1007).

Discussion

We found 45 satDNA families in the genome of A. paranae by means of Next Generation Sequencing and bioinformatic analysis using a low-cost approach. This represents a huge leap in the knowledge of satDNA library3 in Astyanax, a genus where full genome sequencing in A. mexicanus actually gave no information on satellite DNA27. The present results are especially valuable bearing in mind that 26 out of the 30 satDNA families showing FISH signals on A. paranae chromosomes (apart from ApaSat07-6-tel) also showed signals on A. fasciatus and/or A. bockmanni. The absence of FISH signals for a satDNA does not necessarily mean its genomic absence, as it can be in a non-clustered pattern, at cytological level, thus being invisible by FISH. Remarkable examples of this are ApaSat20-18 and ApaSat36-21, which gave no FISH signals in A. paranae A chromosomes but their presence in this species genome is granted by NGS and bioinformatic analyses. In fact, one or both satellites were conspicuously clustered in A. fasciatus and A. bockmanni (see Table 2), demonstrating that a same satDNA family can change its chromosomal distribution pattern during evolution in different species2. Taken together, these results suggest that the three species share most satDNAs. This might be due to a slow rate of satDNA turnover in this genus, but a recent molecular phylogeny performed on more than 70 Astyanax species has shown that the three species analysed here share a same clade, with genetic distances lower than 2%, thus suggesting their recent diversification28. Therefore, the high proportion of shared satellite DNA families between these three species might also be due to their short period of independent evolution. Satellite DNA analysis in species belonging to other clades will provide valuable information on turnover rate of satellite DNA in this genus.

Up to now, only one satDNA was described in Astyanax, using restriction enzymes, i.e., the As51 satDNA15. This is actually the most abundant satDNA in the A. paranae genome, for which reason it is named here ApaSat01-51, being 14 times more abundant in the 0B genome than the second satDNA in abundance (ApaSat02-236). Our present results have thus revealed the power of NGS sequencing combined with the bioinformatic methodology provided by the RepeatExplorer and SatMiner tools, as they allow access to a new level of satellites showing very low abundance. In fact, we have been able to visualize FISH clusters for ApaSat45-113, which represents only 0.001% of the 0B genome. Our results also show that the use of the SatMiner toolkit adds extra power for the high-throughput analysis of satellite DNA since a single RepeatExplorer run in A. paranae uncovered only six satDNA families with 0.0836% minimum abundance. Therefore, the use of SatMiner implied uncovering 39 additional satDNAs and detecting satellites with abundance almost 60 times lower, as shown by Ruiz-Ruano et al.2.

The high-throughput analysis of the satellitome provides ample information on many aspects of a multitude of different satDNA families within the same genome. It is presumable that this kind of analysis will help to reveal general tendencies of this kind of repetitive DNA, and whether they differ among groups of organisms. For instance, the RUL for the 45 satDNA families bioinformatically found in A. paranae (median = 59 bp) was rather shorter than the figures reported in grasshopper species (158 bp in Locusta migratoria2 and 97 bp in Eumigus monticola29). Satellitome analysis in other species will clarify whether there is actually a tendency for length differences between different kinds of organisms. Likewise, in E. monticola, Ruiz-Ruano et al.29 found that satDNAs clustered on the B chromosome were significantly shorter than those located only on the A chromosomes. In A. paranae, however, no significant length difference was found between satellites visualized by FISH on the B chromosome and those non visualized on it (U = 148.5, P = 0.669). In A. paranae, longer satellites tend to be richer in A + T, in consistency with previous observations by Ruiz-Ruano et al.2. However, whereas long satDNAs are less divergent than short ones in the migratory locust genome2, we have not found such an association in A. paranae, perhaps because the latter species actually carries few long satellites.

The second and fourth most abundant satDNAs in the A. paranae genome, ApaSat02-236 and ApaSat04-233 (both showing homology thus constituting the SF1 superfamily), might play a role in centromeric function in these three species as they are localized on the pericentromeric region of many chromosomes. It is usually assumed that the most abundant satDNA plays a centromeric role30. However, in E. monticola, the only satDNA located in the pericentromeric region of all chromosomes is EmoSat08-41, which is the eighth satDNA in order of decreasing abundance29. Likewise, in Astyanax, the only satDNAs showing pericentromeric location in most chromosomes were those belonging to SF1, and ApaSat04-233 was present on all chromosomes in A. fasciatus (see Fig. 4b), but they were only the second and fourth most abundant satDNAs, respectively.

We found two patterns of chromosomal distribution for the A. paranae satDNAs. These were (i) the non-clustered (nc) pattern, referred to satDNAs being invisible by FISH but still abundant in the genome, as indicated by the bioinformatics analysis of Illumina reads and (ii) the clustered (c) pattern, for those satDNAs forming a countable number of large clusters being visible by FISH. Remarkably, although many satellites exhibited the same pattern of distribution in the three species analysed, some satellites nonetheless exhibited distinct patterns between species, especially ApaSat20-18 and ApaSat36-21 which show a non-clustered pattern on the A chromosomes of A. paranae but they are conspicuously clustered on those of A. fasciatus and A. bockmanni (Fig. 3) or else only on those of A. bockmanni (Supplementary Fig. S4). These different patterns of distribution indicate that each satDNA follows its own evolutionary pathway in different species; that is, a satDNA can remain non-clustered in one species while it can become clustered in another species, thus following the pattern of emergence and establishment of satDNA proposed by Ruiz-Ruano et al.2.

It is interesting to note that non-clustered satDNAs tend to show shorter RUL than clustered ones, as this is consistent with the general idea that microsatellites and minisatellites are scattered throughout the genome, whereas long satellites are clustered. However, this observation is only partially correct in A. paranae since at least one non-clustered satellite (ApaSat38-107) was longer than 100 bp which is an usual minimum threshold for long satellites, and several clustered satellites showed RULs about only 20 bp, thus overlapping with the common definition of minisatellites (see Table 2). Our present results thus support the conclusion by Ruiz-Ruano et al.2 that it is not justified to classify satellites according to RUL since satellites of any length may be clustered or not in the genome, a fact also observed in A. paranae.

Due to the large number of chromosomes in the karyotype of the Astyanax species analyzed here, with many A chromosomes showing similar morphology, it was difficult to perform a detailed analysis of satDNA distribution on them. Therefore, the between-species comparison was more superficial for A chromosomes than for B chromosomes. In the case of A chromosomes, we limited the comparison to whether each satellite is clustered on one or more chromosomes of the A complement in each species, whereas for the B chromosomes, which can be easily identified in each species, it was possible to accurately locate each satellite (see Fig. 5). The set of satDNAs located on the BpM chromosome was distributed throughout its whole length, including regions where it had not yet been possible to identify any type of repetitive sequence23,31. The presence of repetitive sequences along the whole BpM chromosome length is consistent with its C-positive banding pattern (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Two satellite DNAs showed conspicuous FISH signals on the B chromosome of A. paranae (BpM), i.e., ApaSat20-18 and ApaSat44-21, are apparently B-specific in this species, as they failed to show FISH signals on A chromosomes of this species (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S6). Remarkably, a search for dimers or multimers of each of these satDNAs in the 0B reads showed that they are not tandemly repeated in the A chromosomes, suggesting that they are actually B-specific in this species. One of these satDNAs (ApaSat44-21) appears to be exclusive to the B chromosome of A. paranae (Supplementary Fig. S6), and thus it might have arisen by duplication and amplification in the BpM chromosome, consistent with the enrichment of repetitive DNA occurring in B chromosomes after their origin32. The other satDNA (ApaSat20-18), however, is shared with the A and B chromosomes of A. fasciatus and A. bockmanni (Fig. 3), thus it could be a good marker for investigating B chromosome origin in these species through detailed sequence analysis.

In several species of Astyanax, it has been shown that the most frequent morphology for the B chromosomes is metacentric and, in some cases, it has been proven that they are isochromosomes15,31. The symmetrical distribution of satellites on the B chromosomes analyzed here is a clear indication that they are, in fact, isochromosomes, i.e., that they derived from an acrocentric chromosome which, through incorrect division of the centromere, gave rise to a metacentric B chromosome with two identical arms, each corresponding to a chromatid, thus showing perfect symmetry. Therefore, a newly emerged iso-B-chromosome should show a very high index of symmetry (1), whereas old ones could show lower symmetry indexes as a result of sequence changes being proportional to their age. The low symmetry index shown by BfMa in A. fasciatus might suggest that it did not arise as an isochromosome. However, the symmetric pattern for five satellites, shown by this B chromosome raises the possibility that it also begun as an isochromosome and that some satellites were gained or lost from a single arm. Since B chromosomes are dispensable, these indels most likely were neutral and their number was proportional to age. On this basis, the BfMa chromosome in A. fasciatus would be older than BfMa in A. paranae and BbM in A. bockmanni.

The presence of B chromosomes showing similar morphology and size in several Astyanax species led Moreira-Filho et al. to suggest their possible common origin33. Recent results by chromosome painting would be consistent with this hypothesis as seven types of B chromosomes shared anonymous repetitive DNA sequences in A. paranae, A. fasciatus and A. bockmanni23, although the physical mapping of four non-anonymous repetitive DNA families, by the same authors, failed to support the common origin hypothesis, except invoking a complex series of gains and/or losses of several kinds of repetitive DNA families23. However, they also compared the DNA sequence of the ITS regions of 45 S ribosomal DNA obtained by PCR amplification on microdissected BpM and BfMa chromosomes and also on genomic DNA from B-lacking individuals of A. paranae and A. fasciatus, and concluded that these two B chromosomes might have had a common origin through hybridization23.

Our present comparative analysis of the distribution of satellite DNA on A chromosomes and three types of B chromosomes (BpM in A. paranae, BfMa in A. fasciatus and BbM in A. bockmanni) has revealed that A and B chromosomes share about similar proportions of satellite families between species. This result is highly consistent with the common descent of A and B chromosomes in these species, including the possibility that these B chromosomes descended from a B chromosome already present in a common ancestor of these three species.

The finding of more B variants in A. fasciatus than in the two other species23 might be an indication that B chromosomes are older in this species. Likewise, the lower symmetry in satDNA location shown by BfMa, suggests that it might be an isochromosome-derived B chromosome with a longer evolutionary pathway of satDNA gains, losses or rearrangements than BpM and BbM ones, which showed perfect symmetry. However, the former observations would also be consistent with the independent and recurrent origin of B chromosomes in different species, provided that centromere misdivision is frequent in this group.

Summing up, our present results add new insights on the different hypotheses previously suggested about B chromosome origin in Astyanax: (1) B chromosomes found in different species of this genus might have derived from a same B chromosome arisen in an ancestor species, but they might have evolved at different rates between species, i.e. faster in A. fasciatus. (2) B chromosomes could have moved between species through interspecific hybridization, as suggested in bees34 and Astyanax23. However, the recent common ancestry of the three species analyzed here28 makes it difficult to distinguish B origin through hybridization from common descent with diversification. (3) Our present results raise the possibility that B chromosome origin is recurrent in these species, so that they might have arisen independently in the three species, thus explaining why B chromosomes in A. fasciatus appear to be older than those in A. paranae and A. bockmanni. The fact that B chromosomes in these three species share a remarkable collection of satDNAs indicates that the origin of these B chromosomes is complex and cannot be elucidated by a marker as dynamic as satellite DNA. Future research should be focused on unveiling the content of these B chromosomes in protein-coding genes, as this kind of genes has recently been uncovered in B chromosomes of several organisms35,36,37,38,39. It is expected that gene content will provide a more clarifying test to the hypothesis of the common origin of B chromosomes in these species, as it predicts similar content for protein-coding genes in B chromosomes from different species.

Materials and Methods

We analyzed individuals of A. paranae, A. fasciatus and A. bockmanni. The sample information is summarized in the Table 4. Previous research showed the presence of B chromosomes in all these locations23,31,40. The samples were collected in accordance with the Brazilian environmental protection legislation (collection permission MMA/IBAMA/SISBIO-number 3245), and the procedures for sampling, maintenance and analysis of the samples were performed in compliance with international guidelines for the care and use of animals followed by the Brazilian College of Animal Experimentation (COBEA) and was approved (protocol 405) by the Bioscience Institute/UNESP Ethics Committee on the Use of Animals (CEUA).

After analysis, specimens were deposited at the fish collection of the Laboratório de Biologia e Genética de Peixes (LBP) at UNESP, Botucatu, São Paulo, Brazil, under the vouchers LBP19572 (A. paranae – Cascatinha River) and LBP19574 (A. fasciatus – Água da Madalena Stream). The specimens from the Alambari River (A. bockmanni) were deposited at the fish collection of the Laboratório de Genética de Peixes at UNESP, Bauru, São Paulo, Brazil. Mitotic chromosomes were obtained from tissue cell suspensions of the anterior kidney according to Foresti et al.41. B chromosomes were identified by C-banding performed following the protocol described by Sumner et al.42. Chromosome morphology was classified, according to Levan et al.43, as metacentric (m), submetacentric (sm), subtelocentric (st), and acrocentric (a). Karyotypes were arranged according to chromosome morphology and size.

We extracted total genomic DNA from liver using a tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel), including a step for RNA removal with RNAse A (Invitrogen). Genomic DNA sequencing was performed on total DNA extracted from one individual carrying 1B and another lacking it, by the Life Sciences Core Facility (LaCTAD) of Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP), using the Illumina HiSeq. 2000 platform (2 × 101 bp paired-end) (Illumina, San Diego, CA), which yielded 14 and 34 Gbp of reads for the 1B and 0B libraries, respectively. We deposited the 0B and 1B genomic libraries in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with accession numbers SRR5461470 and SRR5461471, respectively.

To perform a high-throughput analysis of satellite DNA in the A. paranae genome, we first performed a standard RepeatExplorer9 clustering on 2 × 200,000 reads combined from the 0B and 1B genomic libraries. In this first analysis, we only detected 6 satDNAs. We then followed the protocol suggested by Ruiz-Ruano et al.2 using the satMiner toolkit, in order to detect as many satDNAs as possible in the A. paranae genome. Briefly, the protocol consists of quality trimming with Trimmomatic44 and then clustering a selection of 2 × 200,000 reads with RepeatExplorer, duplicating the number of reads for each new run. Then, we searched for tandem repeated structures in those assembled contigs of clusters with a typical satDNA structure (i.e., spherical or ring-shaped) with Geneious R8.1 software. We then used DeconSeq software45 to filter out reads showing homology with the previously identified clusters. Then, using a sample of the remaining reads, we performed a new RepeatExplorer run.

We performed a homology search between all repeat unit sequences found and grouped them as same sequence variant, same family and same superfamily if identity was higher than 95%, 80% and 50%, respectively. We determined the abundance and divergence for each variant by means of RepeatMasker software46, with the Cross_match search engine, using 10 million reads for each genome. Abundance in the 0B and 1B genomes (A0B and A1B, respectively) was calculated as the proportion of reads mapped for a given satDNA with respect to total mapped reads. We assigned catalog numbers to satDNA families in order of decreasing abundance in the 0B genome, following Ruiz-Ruano et al.2. We named each satDNA family following the criterion suggested by Ruiz-Ruano et al.2. The assembled sequences were deposited in GenBank with accession numbers MF044753-MF044818. We searched for homology with other repetitive sequences in RepBase47.

We calculated the log2 of the quotient between 1B and 0B abundance values (log2 A1B/A0B) to detect changes in satDNA abundance that might be due to abundance differences in the A and B chromosomes. We thoroughly investigated the possible presence in the B-lacking genome of satDNA families that appeared to be B-specific. For this purpose, we first selected pairs of reads in each library separately showing homology with a specific satDNA by using BLAT48 implemented in a custom script (https://github.com/fjruizruano/ngs-protocols/blob/master/mapping_blat_gs.py). Then, we performed a RepeatExplorer clustering with 2 × 2500 of the selected reads. In this case, we used a custom database for annotating the sequences of all assembled satDNAs.

We designed primers in opposite orientation to amplify the 45 satDNAs identified bioinformatically (Supplementary Table S1) as in Ruiz-Ruano et al.2. To generate FISH probes, we performed PCR including digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Roche Applied Science) in the reaction to label the PCR product. For FISH experiments, we used the procedure described in Pinkel et al.49, using high stringency conditions, and the signals were detected with anti-digoxigenin-rhodamine (Roche Applied Science). We analyzed a minimum of five metaphases for each hybridization experiment. The two cytogenetic preparations of A. paranae used for FISH, were not from the same individuals used for DNA sequencing. The FISH experiments on A. fasciatus were carried out using material from two samples, whereas we used material from only one sample for FISH on A. bockmanni. These individuals had only one B chromosome by cell and we confirmed that we used individuals with the same type of B chromosome for A. paranae and A. fasciatus by C-banding. Statistical analysis was performed by the Shapiro-Wilks test to ascertain whether variables fitted a normal distribution, Levene’s test to test homoscedasticity, the Fisher exact test, and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney and Spearman rank correlation tests, by means of the Statistica 6.0 software.

Change history

08 January 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Kuhn, G. C. S. Satellite DNA transcripts have diverse biological roles in Drosophila. Heredity 115, 1 (2015).

Ruiz-Ruano, F. J., López-León, M. D., Cabrero, J. & Camacho, J. P. M. High-throughput analysis of the satellitome illuminates satellite DNA evolution. Sci. Rep. 6 (2016).

Fry, K. & Salser, W. Nucleotide sequences of HS-α satellite DNA from kangaroo rat Dipodomys ordii and characterization of similar sequences in other rodents. Cell 12, 1069–1084 (1977).

Holmquist, G. P. & Dancis, B. Telomere replication, kinetochore organizers, and satellite DNA evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 76, 4566–4570 (1979).

Plohl, M., Meštrović, N. & Mravinac, B. Centromere identity from the DNA point of view. Chromosoma 123, 313–325 (2014).

Garrido-Ramos, M. A. Satellite DNA in plants: more than just rubbish. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 146, 153–170 (2015).

Singer, M. F. Highly repeated sequences in mammalian genomes. Int. Rev. Cytol. 76, 67–112 (1982).

Vicari, M. R. et al. Satellite DNA and chromosomes in Neotropical fishes: methods, applications and perspectives. J. Fish Biol. 76, 1094–1116 (2010).

Novák, P., Neumann, P., Pech, J., Steinhaisl, J. & Macas, J. RepeatExplorer: a Galaxy-based web server for genome-wide characterization of eukaryotic repetitive elements from next-generation sequence reads. Bioinformatics 29, 792–793 (2013).

Slamovits, C. H. & Rossi, M. S. Satellite DNA: agent of chromosomal evolution in mammals. A review. Mastozoología Neotrop. 9, 297–308 (2002).

Palomeque, T. & Lorite, P. Satellite DNA in insects: a review. Heredity 100, 564–573 (2008).

Plohl, M., Meštrović, N. & Mravinac, B. Satellite DNA evolution. Repetitive DNA 7, 126–152 (Karger Publishers, 2012).

Haaf, T., Schmid, M., Steinlein, C., Galetti, P. M. Jr. & Willard, H. F. Organization and molecular cytogenetics of a satellite DNA family from Hoplias malabaricus (Pisces, Erythrinidae). Chromosome Res. 1, 77–86 (1993).

Koehler, M. R., Haaf, T., Guttenbach, M., Schartl, M. & Schmid, M. Cytogenetics of the genus Leporinus (Pisces, Anostomidae). II. Molecular cytogenetics, organization and evolutionary conservation of a chromosome-specific satellite DNA from Leporinus obtusidens. Chromosome Res. 5, 325–331 (1997).

Mestriner, C. A. et al. Structural and functional evidence that a B chromosome in the characid fish Astyanax scabripinnis is an isochromosome. Heredity 85, 1–9 (2000).

Jesus, C. M., Galetti, P. M. Jr., Valentini, S. R. & Moreira-Filho, O. Molecular characterization and chromosomal localization of two families of satellite DNA in Prochilodus lineatus (Pisces, Prochilodontidae), a species with B chromosomes. Genetica 118, 25–32 (2003).

Vicente, V. E., Bertollo, L. A. C., Valentini, S. R. & Moreira-Filho, O. Origin and differentiation of a sex chromosome system in Parodon hilarii (Pisces, Parodontidae). Satellite DNA, G-and C-banding. Genetica 119, 115–120 (2003).

Da Silva, E. L., Busso, A. F. & Parise-Maltempi, P. P. Characterization and genome organization of a repetitive element associated with the nucleolus organizer region in Leporinus elongatus (Anostomidae: Characiformes). Cytogenet. Genome Res. 139, 22–28 (2013).

Utsunomia, R. et al. Uncovering the ancestry of B chromosomes in Moenkhausia sanctaefilomenae (Teleostei, Characidae). PLoS One 11, e0150573 (2016).

Eschmeyer, W. N. & Fong, J. D. Catalog of fishes: Species by family/subfamily (2016).

Morelli, S., Bertollo, L. A. C., Foresti, F., Moreira-Filho, O. & Almeida-Toledo, L. F. Cytogenetic considerations on the genus Astyanax (Pisces, Characidae). I. Karyotypic variability. Caryologia 36, 235–244 (1983).

Oliveira, C., Foresti, F. & Hilsdorf, A. W. S. Genetics of Neotropical fish: from chromosomes to populations. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 35, 81–100 (2009).

Silva, D. M. Z. A. et al. Origin of B chromosomes in the genus Astyanax (Characiformes, Characidae) and the limits of chromosome painting. Mol. Genet. Genomics 291, 1407–1418 (2016).

Hashimoto, D. T., Ferguson-Smith, M. A., Rens, W., Foresti, F. & Porto-Foresti, F. Chromosome mapping of H1 histone and 5 S rRNA gene clusters in three species of Astyanax (Teleostei, Characiformes). Cytogenet. Genome Res. 134, 64–71 (2011).

Silva, D. M. Z. A. et al. Chromosomal organization of repetitive DNA sequences in Astyanax bockmanni (Teleostei, Characiformes): dispersive location, association and co-localization in the genome. Genetica 141, 329–336 (2013).

Piscor, D. & Parise-Maltempi, P. P. Microsatellite organization in the B Chromosome and A chromosome Complement in Astyanax (Characiformes, Characidae) species. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 148, 44–51 (2016).

McGaugh, S. E. et al. The cavefish genome reveals candidate genes for eye loss. Nat. Commun. 5, 5307 (2014).

Rossini, B. C. et al. Highlighting Astyanax Species Diversity through DNA Barcoding. PLoS One 11, e0167203 (2016).

Ruiz-Ruano, F. J., Cabrero, J., López-León, M. D. & Camacho, J. P. M. Satellite DNA content illuminates the ancestry of a supernumerary (B) chromosome. Chromosoma 1–14 (2016).

Melters, D. P. et al. Comparative analysis of tandem repeats from hundreds of species reveals unique insights into centromere evolution. Genome Biol. 14, R10 (2013).

Silva, D. M. Z. A. et al. Delimiting the origin of a B chromosome by FISH mapping, chromosome painting and DNA sequence analysis in Astyanax paranae (Teleostei, Characiformes). PLoS One 9, e94896 (2014).

Banaei-Moghaddam, A. M. et al. Genes on B chromosomes: old questions revisited with new tools. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Regul. Mech. 1849, 64–70 (2015).

Moreira-Filho, O., Fenocchio, A. S., Pastori, M. C. & Bertollo, L. A. C. Occurrence of a metacentric macrochromosome B in different species of the genus Astyanax (Pisces, Characidae, Tetragonopterinae). Cytologia. 66, 59–64 (2001).

Tosta, V. C. et al. Possible introgression of B chromosomes between bee species (genus Partamona). Cytogenet. Genome Res. 144, 220–226 (2014).

Martis, M. M. et al. Selfish supernumerary chromosome reveals its origin as a mosaic of host genome and organellar sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 13343–13346 (2012).

Makunin, A. I. et al. Genes on B chromosomes of vertebrates. Mol. Cytogenet. 7, 99 (2014).

Valente, G. T. et al. Origin and evolution of B chromosomes in the cichlid fish Astatotilapia latifasciata based on integrated genomic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. msu148 (2014).

Ma, W. et al. Rye B chromosomes encode a functional Argonaute‐like protein with in vitro slicer activities similar to its A chromosome paralog. New Phytol. 213, 916–928 (2017).

Navarro-Domínguez, B. et al. Protein-coding genes in B chromosomes of the grasshopper Eyprepocnemis plorans. Sci. Rep. 7, 45200 (2017).

Daniel, S. N., Hashimoto, D. T., Pansonato-Alves, J. C., Foresti, F. & Porto-Foresti, F. Cytogenetic characterization of distinct B chromosomes in a population of the fish Astyanax bockmanni (Teleostei, Characiformes). Caryologia 65, 229–233 (2012).

Foresti, F., Almeida-Toledo, L. F. & Toledo-Filho, S. A. Polymorphic nature of nucleolus organizer regions in fishes. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 31, 137–144 (1981).

Sumner, A. T. A simple technique for demonstrating centromeric heterochromatin. Exp. Cell Res. 75, 304–306 (1972).

Levan, A., Fredga, K. & Sandberg, A. A. Nomenclature for centromeric position on chromosomes. Hereditas 52, 201–220 (1964).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Schmieder, R. & Edwards, R. Fast identification and removal of sequence contamination from genomic and metagenomic datasets. PLoS One 6, e17288 (2011).

Smit, A., Hubley, R. & Green, P. RepeatMasker Open-4.0.

Bao, W., Kojima, K. K. & Kohany, O. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mob. DNA 6, 11 (2015).

Kent, W. J. BLAT—the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 12, 656–664 (2002).

Pinkel, D., Straume, T. & Gray, J. W. Cytogenetic analysis using quantitative, high-sensitivity, fluorescence hybridization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 83, 2934–2938 (1986).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by grants from the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) to DMZA (2013/24367-0) and FF (2014/09634-5), grants from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) to FPF (448012/2014-6) and FF and by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed the experiments. D.M.Z.A., R.U., S.N.D., D.T.H. obtained the materials for molecular and cytological analysis. D.M.Z.A., R.U., F.J.R.-R. performed the bioinformatics analysis. J.P.M.C. performed statistical analyses. All authors participated in the analysis and discussion of results and paper writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Silva, D.M.Z.d.A., Utsunomia, R., Ruiz-Ruano, F.J. et al. High-throughput analysis unveils a highly shared satellite DNA library among three species of fish genus Astyanax. Sci Rep 7, 12726 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12939-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12939-7

This article is cited by

-

Evolution of ancient satellite DNAs in extant alligators and caimans (Crocodylia, Reptilia)

BMC Biology (2024)

-

Fast satellite DNA evolution in Nothobranchius annual killifishes

Chromosome Research (2023)

-

Novel selectively amplified DNA sequences in the germline genome of the Japanese hagfish, Eptatretus burgeri

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Satellitome analysis illuminates the evolution of ZW sex chromosomes of Triportheidae fishes (Teleostei: Characiformes)

Chromosoma (2022)

-

Meiotic behavior, transmission and active genes of B chromosomes in the cichlid Astatotilapia latifasciata: new clues about nature, evolution and maintenance of accessory elements

Molecular Genetics and Genomics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.