Abstract

Gut bacterial translocation to the blood may play an important role in the development of insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Here, we performed an interventional randomised control study to investigate whether probiotics could reduce bacterial translocation and cause changes in the gut microbiota. Seventy Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes were randomised to two groups: the probiotic group drank Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota-fermented milk, while the control group ingested no probiotics. The trial was conducted for 16 weeks. At baseline, 8 and 16 weeks, the gut microbiota composition in feces and blood, fecal organic acids, and other biochemical parameters were measured. At the end of the study, the fecal counts of the Clostridium coccoides group and Clostridium leptum subgroup in the probiotic group were significantly higher than in the control group. As expected, the fecal counts of total Lactobacillus were significantly higher in the probiotic group. Intriguingly, the total count of blood bacteria was significantly lower in the probiotic group. However, fecal organic acids were comparable between the two groups. Our results showed that probiotic administration reduced bacterial translocation and altered the gut microbiota in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past decades, the incidence of diabetes has increased worldwide1. A great change in dietary habits characterized by an increased intake of fat is considered to be responsible for the dramatic rise in metabolic diseases2. In this situation, the gut microbiota is a great topic in the research of this field.

Short-chain fatty acids formed from the fermentation of dietary fiber by the gut microbiota have been found to be associated with incretin secretion3, intestinal gluconeogenesis4, insulin sensitivity in adipocytes5, and insulin secretion via activation of the parasympathetic nerve6. Thus, interesting roles of the gut microbiota in glucose metabolism are closely linked to the pathogenesis of diabetes and manipulation of the human gut microbiota might provide important clues regarding a new therapeutic target for diabetes.

The leaky gut has also been attracting a great deal of attention in the context of metabolic diseases. In particular, a fat-rich diet was shown to lead to changes in the gut microbiota that strongly increased intestinal permeability due to malfunction of tight junction proteins such as occuludin and ZO-17. This results in increased plasma levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a condition known as “metabolic endotoxemia”, which causes low-grade inflammation and eventually insulin resistance8. In animal models, our group previously showed that probiotic administration improved insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in diet-induced obesity mice with reduction in endotoxemia9, and an epidemiological study also determined that an increased blood concentration of 16 s ribosomal DNA from gut bacteria was a risk factor for developing diabetes in a general population10. Considering the results of these previous studies, bacterial translocation due to leaky gut could play a still unidentified role in the pathophysiology of diabetes through insulin resistance and/or other unknown mechanisms.

Previously, we reported for the first time the presence of gut dysbiosis and a higher rate of detection of live gut bacteria in the blood of Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes compared to non-diabetes11, suggesting that bacterial translocation occurs in type 2 diabetes. However, the causal relation between gut dysbiosis and bacterial translocation remained unclear because our previous study used a cross-sectional design. Addressing this issue would require an interventional trial using probiotics that can modify the gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Among various probiotics, the beneficial effect of the probiotic Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota (LcS) on the gut microbiota and intestinal environment has been proven in healthy individuals12 and the elderly13. In an animal diabetes model, improvement of glucose metabolism by LcS was reported previously14. Furthermore, fecal butyric acids were known to play protective roles in intestinal barrier function through reassembly of tight junctions15, and other fecal organic acids also improved intestinal barrier function in vitro 16 and in vivo model17.

Therefore, we performed an interventional randomised control study to investigate the effects of daily intake of probiotic LcS-fermented milk on the gut microbiota, fecal organic acids, and bacterial translocation in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of the 70 patients recruited in this study, 35 were assigned to the probiotic group and 35 to the control group. In the probiotic group, 35 patients completed the 16-week intervention but one patient was excluded from the final analysis due to onset of acute enteritis. In the control group, 34 patients completed the 16-week trial, while one declined participation after randomisation (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics of the patients who completed the study are summarised in Table 1. The rate of men in the probiotic group was significantly higher than the control group (p < 0.05). However, other parameters including age, body mass index (BMI), fasting blood glucose and HbA1c were comparable between the two groups (Table 1). Therefore, the effect of difference in rate of sex on the results was considered to be small.

Flow diagram of patient recruitment. Seventy patients were randomly allocated to either the probiotic group or the control group. One patient in the control group declined to participate in the study, and one patient in the probiotic group was excluded from the analysis due to the onset of acute enteritis during the study period. The remaining 68 patients were analysed.

Serial changes of fecal microbiota before and after probiotic administration

Table 2 shows the serial changes of fecal microbiota after probiotic administration. At baseline there were no significant differences in fecal bacterial counts between the two groups. However, the counts of total Lactobacillus and the L. casei subgroup at 8 and 16 weeks were significantly higher in the probiotic group compared with the control group (p < 0.01) and were significantly increased compared with baseline (p < 0.01). The detection rate of the L. casei subgroup in feces was significantly higher in the probiotic group compared with the control group at 8 and 16 weeks (p < 0.01). In addition, the counts of the L. gasseri subgroup at 8 and 16 weeks (p < 0.05) and the L. reuteri subgroup at 16 weeks (p < 0.05) were significantly increased in the probiotic group compared with baseline, while no such changes were observed in the control group. On the other hand, the counts of Bifidobacterium, Atopobium cluster, total Lactobacillus, and L. fermentum at 16 weeks were significantly increased and those of Prevotella at 16 weeks were significantly decreased in the control group compared with baseline (p < 0.05). Further, among the obligate anaerobes, the counts of the C. coccoides group and the C. leptum subgroup at 16 weeks after probiotic administration were significantly higher in the probiotic group compared with the control group (p < 0.05), and linear mixed model analysis showed the same results (S2 Table).

Serial changes of fecal organic acids and pH before and after probiotic administration

The results of serial changes of fecal organic acids and pH are presented in Table 3. At baseline, there were no significant differences in the fecal concentrations of total organic acids between the two groups, but the concentration of butyric acid was significantly higher in the probiotic group compared with the control group (p < 0.05). At 8 and 16 weeks, the concentrations of total organic acids and butyric acid were significantly decreased in the probiotic group compared with baseline (P < 0.05), and fecal pH at 8 and 16 weeks in the probiotic group was significantly increased compared with baseline. However, the levels of these organic acids and the fecal pH at 8 and 16 weeks were not significantly different between the two groups, and linear mixed model analysis (S3 Table) showed the significant decrease of valeric acids at 16 weeks in the probiotic group compared to the control group (p < 0.05).

Serial changes of counts and detection rates of gut bacteria in the blood before and after probiotic administration

Gut bacteria in the blood of diabetes patients were detected in both the control and the probiotic groups during the study period; the detection rates were comparable between the two groups (Table 4), and did not change significantly between baseline and 16 weeks. However, the total count of gut bacteria in the blood at 16 weeks was significantly lower in the probiotic group compared with the control group (p < 0.05). Figure 2 presented the results of total counts of gut bacteria in blood as graphs.

Total counts of bacteria in blood of the control and probiotic groups during the study period. Horizontal bars represent medians, and columns indicate interquartile ranges (IQRs). When a data point was above Q3 (the third quartile) + 1.5 × IQR or below Q1 (the first quartile) − 1.5 × IQR, it was defined as an outlier (white circle). Upper or lower whisker represents the maximum or minimum value if there are no outliers. Upper whiskers at 0 and 8 weeks in the probiotic group and 16 weeks in the control group represented the maximum values within Q3 + 1.5 × IQR as outliers were found. On the other hand, all lower whiskers represented the minimum values. *p < 0.05 vs. Control

Serial changes of clinical parameters and inflammatory markers before and after probiotic administration

As shown by Table 5, the level of hs-CRP at 16 weeks was significantly increased in the probiotic group compared with baseline (p < 0.01), however changes in hs-CRP were not significantly different between the two groups. Then, changes in other inflammatory markers such as IL-6, TNF-α, and LBP were comparable between the two groups. The levels of HbA1c at 16 weeks in the control (p < 0.05) and probiotic (p < 0.01) groups were slightly increased compared with baseline, however changes of HbA1c, fasting blood glucose, and glycoalbumin were comparable between the two groups. The levels of T-CHO in the probiotic group and HDL-C in the control group were significantly increased compared with baseline (p < 0.05). Additionally, linear model analysis (S4 Table) showed the significant decrease of HDL-C at 8 weeks in the probiotic group compared to the control group (p < 0.05).

Discussion

There have been several reports thus far regarding the effects of probiotic LcS on the gut microbiota and inflammatory markers in metabolic syndrome18,19 and on insulin sensitivity in healthy individuals20. In addition, the effects of other probiotics on insulin sensitivity21 and inflammatory markers22 in diabetes have been reported. However, no clinical trials have adopted a primary outcome of bacterial translocation specifically in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. In the present study, we demonstrated for the first time that administration of LcS-fermented milk could reduce gut bacterial translocation to the blood in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Previous studies clearly showed that persons with higher levels of gut bacterial DNA in the blood were at risk of developing diabetes in the future10, and in animal models a high-fat diet caused gut bacterial DNA to be phagocytosed by macrophages and to subsequently accumulate in the adipose tissue23. Furthermore, the present study confirmed the presence of bacteremia in type 2 diabetes, as did our previous study11. Thus, gut bacterial translocation to the blood might play important roles in chronic low-grade inflammation in obesity and diabetes, and as such our main finding that probiotics reduced the counts of live gut bacteria in the blood is considered to be highly significant. Although in our study total counts of bacteria in the blood were decreased by probiotic, none of the single bacteria were not decreased. The reasons for that remain unknown. However, some bacteria translocated to the blood, but some ones never did, indicating the presence of selectivity of intestinal barrier function to bacterial translocation. Regarding the validity of the methodology for analysing gut microbiota in fecal samples, we previously used YIF-SCAN® to show that five potential gut pathogens were approximately 10,000 times less prevalent than six predominant anaerobic groups24. For detection of such small numbers of pathogens at subdominant levels, the highly sensitive YIF-SCAN® approach might be appropriate rather than routine DNA-based PCR or next-generation sequencing methods. In particular, YIF-SCAN® for blood microbiota analysis (sensitivity: approximately 1 cell/1 mL-blood)25 could lead to the precise analysis of bacterial translocation to the blood. In addition, a previous report using our same method showed a significant correlation between the positivity of bacteria in the mesenteric lymph nodes and blood samples after pancreatoduodenectomy26. Therefore, our method in this study can evaluate bacterial translocation.

One previous study showed that individuals with metabolic syndrome had higher concentration of fecal Zonulin and calprotectin and increased Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio in fecal samples, and that probiotic LcS did not affect this18. However, the number of probiotic cells was half of that used in our study (4 × 1010 cells), and the study period of 12 weeks was shorter than that in our study (16 weeks). Indeed, in our study bacterial translocation was not reduced at 8 weeks after probiotic administration. Therefore, in order to accurately detect a reduction in bacterial translocation, more probiotic cells and longer administration periods might be necessary.

Regarding the analyses of the gut microbiota in feces in this study, the counts of the C. coccoides group and C. leptum subgroup were significantly increased at 16 weeks after probiotic administration compared to control, and those of total Lactobacillus were increased at 8 and 16 weeks. Additionally, the fecal counts of L. reuteri and L. gasseri species were significantly increased at 16 weeks after probiotic administration compared to baseline. The C. coccoides group of bacteria is known to be one of the most predominant in the human gut27,28. According to our previous study11, fecal counts of the C. coccoides group in type 2 diabetes patients were significantly lower than in patients without diabetes (diabetes/non-diabetes: 9.4 ± 0.8 / 9.8 ± 0.5 log10 cells/g of feces). However, in the present study, the fecal counts of the C. coccoides group at 16 weeks after probiotic administration recovered to non-diabetes levels (9.8 ± 0.4 log10 cells/g of feces), as shown in Table 2. Therefore, some key species in the C. coccoides group might be sensitive to probiotics, and a comprehensive analysis is needed to identify which specific bacteria contribute to maintaining gut health in diabetes patients.

Importantly, L. casei, L. reuteri, and L. gasseri, which were present in higher numbers in fecal samples in the probiotic group in this study compared to the baseline. LcS is reported to suppress colon inflammation and play some roles in the maintenance of intestinal barrier function29, and reduce LBP levels in diet-induced obesity mice9. Especially, counts of L. casei in the feces greatly increased after probiotic administration, suggesting the main contribution of LcS to decreased bacterial translocation. Moreover, L. reuteri increases mucus thickness in addition to its beneficial effects on the expression of tight junction proteins30,31,32, and L. gasseri reduces apoptosis, which could be relevant in protecting epithelial barrier integrity33. These two bacteria might, at least in part, contribute to decreased bacterial translocation. However, inflammatory markers such as LBP, IL-6, TNF-α and hs-CRP were not reduced by probiotic administration in our study, and glycaemic control represented by HbA1c, glycoalbumin and FPG did not show clinically significant changes. In previous studies by our group, LcS (4 × 1010 cells) administration increased the levels of fecal organic acids and the fecal counts of Bifidobacterium in healthy children34 and the elderly35. Thus, in cases where the intestinal environment is improved by LcS, increased levels of Bifidobacterium and organic acids in feces could be expected in addition to the increased levels of Lactobacillus. However, this was not found in the present study, suggesting that the effects of LcS on the gut microbiota and intestinal environment might differ between healthy patients and those with type 2 diabetes. Therefore, LcS is considered to only partially improve gut dysbiosis in type 2 diabetes, and further research exploring more efficient probiotics (e.g., multispecies probiotics and/or more probiotic cells) or synbiotics, defined as “mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics”, is necessary.

Our study has several limitations. First, the number of patients (n = 68) was too small to evaluate changes of the detection rate of gut bacteria in the blood before and after probiotic administration. Second, as our study did not use a double-blind design, patients were aware they were taking probiotics and may have been familiar with their effects on the gut microbiota, which might have biased the results of the study. Specifically, life style of food habits in the probiotic group might be affected because of a non-blinded study. Third, detection rates of LcS in the feces of the probiotic group were not 100% at 8 and 16 weeks despite instruction of sure consumption of probiotic. However, as its adherence rate was not so low, the influence of adherence on our results was small.

In conclusion, our results showed that probiotic administration reduced bacterial translocation with a partial change of gut microbiota in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. However, in order to further ameliorate gut dysbiosis and reduce chronic inflammation, more efficient procedures may be necessary, including the application of certain synbiotics and/or more probiotic cells with longer administration periods.

Subjects and Methods

Participants

Type 2 diabetes patients with stable glycemic control were recruited from the outpatient clinic of Juntendo University Hospital between February 2015 and February 2016. The following inclusion criteria were applied at study registration: 1) 30 < age < 79 years, 2) 6.0 ≤ HbA1c (NGSP) < 8.0% and 3) treatment with only diet and exercise or medicines excluding α-glucosidase inhibitors. Patients with HbA1c ≥ 8.0% were excluded because their medications might be changed during the study period. The selected patients were excluded from the study if any of the following conditions was diagnosed at registration: 1) serious kidney disease (serum creatinine level ≥ 2.0 mg/dL and / or haemodialysis), 2) serious liver disease excluding fatty liver, 3) inflammatory bowel disease, 4) 20 < body mass index ≤ 35, 5) past history of digestive surgery and 6) not suitable for the study (patients with irregular visits to the hospital and poor adherence to therapy). The study protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Juntendo University in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and current legal regulations in Japan. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before enrolment in the study. This study was registered on the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry, which is a non-profit organization in Japan and meets the requirements of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (UMIN000018246, registration date: February 20, 2015).

Study design

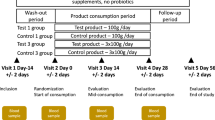

Previous reports showed that the administration of LcS improved the intestinal environment in the elderly (one arm: n = 10)13 and in healthy individuals with soft stools (one arm: n = 17)12, respectively. However, a pilot study showed no effects of LcS administration on insulin sensitivity or chronic inflammation in metabolic syndrome (one arm: n = 15)36. In reference to these previous reports, we aimed to register 70 diabetes subjects (35 patients in each group), taking into consideration the possibility of several dropouts. Thus, 70 patients who met the above criteria were assigned randomly to either the probiotic group, which consumed LcS-fermented milk for 16 weeks, or the control group, which did not receive a probiotic intervention. Randomization was performed using a computer-based dynamic allocation system with minimization procedure to balance for age of patients (Soiken, Inc., Osaka, Japan). The primary endpoints were changes of the gut microbiota, detection rates and bacterial blood counts at the end of the study relative to the baseline values. The secondary endpoints were changes from baseline to the end of the study in HbA1c, lipids and adiponectin, as well as in the following inflammatory markers: high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), lipopolysaccharide binding protein (LBP), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). During the study period, medications for diabetes were not changed. Samples for the analysis of gut microbiota in the blood and feces, fecal organic acids and biochemical assays were obtained after overnight fasts at each hospital visit (0, 8 and 16 weeks).

Ingestion of LcS-fermented milk

The test beverage was LcS-fermented milk (product name: Yakult 400LT, Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The composition of each 80-ml bottle was as follows: energy, 43 kcal; protein, 1.0 g; lipids, 0.1 g; carbohydrates, 9.5 g; and sodium, 18 mg. The number of LcS cells was 4 × 1010 or more at the time of ingestion. The participants in the probiotic group consumed one bottle of LcS-fermented milk every day for 16 weeks at breakfast; this was ensured by up to three telephone calls to each patient, as necessary, just before their visit to the hospital (0, 8 and 16 weeks) during the study period. On the other hand, the participants in the control group consumed no LcS-fermented milk. During the study period, all participants were prohibited from consuming any other probiotics or prebiotics. In addition, at 0 week each physician instructed the participants in the probiotic group to restrict their calorie intake by 40 kcal/day considering the additional calories in the LcS-fermented milk, and monitored adverse events at each visit.

Determination of bacterial count by 16S and 23S rRNA–targeted reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and qPCR

At each hospital visit, patients defecated at their home, and brought with refrigerants to the hospital. After collecting them, feces were stored immediately at −80 degrees (for organic acids analysis) and 4 degrees (for microbiota analysis), respectively. Fecal samples were weighed and then suspended in 9 volumes of RNAlater® (Ambion, Austin, TX). One milliliter of blood was added to 2.0 ml of RNAprotect bacterial reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) immediately after collection. After incubation at room temperature for 10 min, the fecal samples were stored at −20 °C. Blood samples were stored at −80 °C, and then transported to the Yakult Central Institute. To quantify the bacteria present in the samples, we examined the gut microbiota composition and plasma levels of the gut bacteria by using the 16S and 23S rRNA–targeted RT-qPCR, Yakult Intestinal Flora-SCAN (YIF-SCAN®). Three serial dilutions of the extracted RNA sample were used for bacterial rRNA–targeted RT-qPCR24,25,37,38, and the threshold cycle values in the linear range of the assay were applied to the standard curve to obtain the corresponding bacterial cell count in each nucleic acid sample. These data were then used to determine the number of bacteria per sample. The specificity of the RT-qPCR assay using group-, genus- or species-specific primers was determined as described previously24,25,37,38. For the enumeration of LcS in feces, Propidium monoazide (Biotium, Inc, CA, USA) treatment of fecal samples, the fecal DNA extraction and qPCR analysis was performed by the methods as described previously27,39,40. The sequences of the primers are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Measurement of organic acids and pH in fecal samples

The concentrations of organic acids and pH in the fecal samples were measured as described previously38. Briefly, the fecal sample was homogenised in 4 volumes of 0.15 µM perchloric acid and allowed to stand at 4 °C for 12 h. The suspension was centrifuged at 20,400 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. The resulting supernatant was passed through a filter with a pore size of 0.45 μm (Millipore Japan, Tokyo). The sample was analysed for organic acids using the Waters HPLC system (Waters 432 Conductivity Detector; Waters Co., Milford, MA) and pH in feces was analysed by IQ 150 pH/Thermometer (IQ Scientific Instruments, Inc., Carlsbad, CA).

In addition, all analyses, including those of the gut microbiota in feces and blood, were performed blindly.

Biochemical assays

Serum lipids (total cholesterol [T-CHO], high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C], low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C] and triglycerides [TG]), fasting blood glucose (FBG) and HbA1c were measured with standard techniques. The plasma levels of hs-CRP, IL-6 and TNF-α were measured by latex nephelometry, chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in a private laboratory (SRL Laboratory, Tokyo), respectively. The plasma level of LBP was measured by human LBP ELISA kit (Hycult Biotech, the Netherlands).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed by a private company (Soiken, Inc., Osaka, Japan) with the SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (for normally distributed data) and median (interquartile range; for data with skewed distribution). Comparisons of the results before and after probiotic administration and between the two groups were analysed using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test and Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. In addition, the analyses by linear mixed model were performed for comparisons of the values between the two groups. The detection rates of fecal and blood bacteria and fecal organic acids between the two groups were analysed by Fisher’s direct test, and comparison of the detection rate of blood bacteria between baseline and 16 weeks was analysed by McNemar’s test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

References

Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet (London, England) 387, 1513–1530, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00618-8 (2016).

Mazidi, M., Pennathur, S. & Afshinnia, F. Link of dietary patterns with metabolic syndrome: analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutr & Diabetes 7, e255, https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2017.11 (2017).

Tolhurst, G. et al. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion via the G-protein-coupled receptor FFAR2. Diabetes 61, 364–371, https://doi.org/10.2337/db11-1019 (2012).

De Vadder, F. et al. Microbiota-generated metabolites promote metabolic benefits via gut-brain neural circuits. Cell 156, 84–96, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.016 (2014).

Kimura, I. et al. The gut microbiota suppresses insulin-mediated fat accumulation via the short-chain fatty acid receptor GPR43. Nat Commun 4, 1829, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2852 (2013).

Perry, R. J. et al. Acetate mediates a microbiome-brain-beta-cell axis to promote metabolic syndrome. Nature 534, 213–217, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18309 (2016).

Cani, P. D. et al. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 57, 1470–1481, https://doi.org/10.2337/db07-1403 (2008).

Cani, P. D. et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 56, 1761–1772, https://doi.org/10.2337/db06-1491 (2007).

Naito, E. et al. Beneficial effect of oral administration of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on insulin resistance in diet-induced obesity mice. J of Applied Microbiol 110, 650–657, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04922.x (2011).

Amar, J. et al. Involvement of tissue bacteria in the onset of diabetes in humans: evidence for a concept. Diabetologia 54, 3055–3061, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-011-2329-8 (2011).

Sato, J. et al. Gut dysbiosis and detection of “live gut bacteria” in blood of Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 37, 2343–2350, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-2817 (2014).

Matsumoto, K. et al. Effects of a probiotic fermented milk beverage containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on defecation frequency, intestinal microbiota, and the intestinal environment of healthy individuals with soft stools. J Biosci Bioeng 110, 547–552, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2010.05.016 (2010).

Nagata, S. et al. Effect of the continuous intake of probiotic-fermented milk containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on fever in a mass outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis and the faecal microflora in a health service facility for the aged. Br J Nutr 106, 549–556, https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711451100064X (2011).

Matsuzaki, T., Yamazaki, R., Hashimoto, S. & Yokokura, T. Antidiabetic effects of an oral administration of Lactobacillus casei in a non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) model using KK-Ay mice. Endocr J 44, 357–365 (1997).

Miao, W. et al. Sodium Butyrate Promotes Reassembly of Tight Junctions in Caco-2 Monolayers Involving Inhibition of MLCK/MLC2 Pathway and Phosphorylation of PKCbeta2. Int J of Mol Sci 17, doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17101696 (2016).

Hsieh, C. Y. et al. Strengthening of the intestinal epithelial tight junction by Bifidobacterium bifidum. Physiol rep 3, https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.12327 (2015).

Tong, L. C. et al. Propionate Ameliorates Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis by Improving Intestinal Barrier Function and Reducing Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Front Pharmacol 7, 253, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2016.00253 (2016).

Stadlbauer, V. et al. Lactobacillus casei Shirota Supplementation Does Not Restore Gut Microbiota Composition and Gut Barrier in Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized Pilot Study. PloS One 10, e0141399, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141399 (2015).

Leber, B. et al. The influence of probiotic supplementation on gut permeability in patients with metabolic syndrome: an open label, randomized pilot study. Eur J Clin Nutr 66, 1110–1115, https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2012.103 (2012).

Hulston, C. J., Churnside, A. A. & Venables, M. C. Probiotic supplementation prevents high-fat, overfeeding-induced insulin resistance in human subjects. Br J Nutr 113, 596–602, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114514004097 (2015).

Mobini, R. et al. Metabolic effects of Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Obes Metab, https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.12861 (2016).

Asemi, Z., Zare, Z., Shakeri, H., Sabihi, S. S. & Esmaillzadeh, A. Effect of multispecies probiotic supplements on metabolic profiles, hs-CRP, and oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Nutr Metab 63, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1159/000349922 (2013).

Amar, J. et al. Intestinal mucosal adherence and translocation of commensal bacteria at the early onset of type 2 diabetes: molecular mechanisms and probiotic treatment. EMBO Mol Med 3, 559–572, https://doi.org/10.1002/emmm.201100159 (2011).

Matsuda, K. et al. Establishment of an analytical system for the human fecal microbiota, based on reverse transcription-quantitative PCR targeting of multicopy rRNA molecules. Appl Environ Microbiol 75, 1961–1969, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01843-08 (2009).

Sakaguchi, S. et al. Bacterial rRNA-targeted reverse transcription-PCR used to identify pathogens responsible for fever with neutropenia. J Clin Microbiol 48, 1624–1628, https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01724-09 (2010).

Yokoyama, Y. et al. Effect of Perioperative Synbiotic Treatment on Bacterial Translocation and Postoperative Infectious Complications after Pancreatoduodenectomy. Dig Surg 33, 220–229, https://doi.org/10.1159/000444459 (2016).

Matsuki, T., Watanabe, K., Fujimoto, J., Takada, T. & Tanaka, R. Use of 16S rRNA gene-targeted group-specific primers for real-time PCR analysis of predominant bacteria in human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol 70, 7220–7228, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.70.12.7220-7228.2004 (2004).

Hayashi, H., Sakamoto, M., Kitahara, M. & Benno, Y. Diversity of the Clostridium coccoides group in human fecal microbiota as determined by 16S rRNA gene library. FEMS Microbiol Lett 257, 202–207, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00171.x (2006).

Okubo, H. et al. Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota protects against nonalcoholic steatohepatitis development in a rodent model. Am J of Physiol Gastrointest and Liver Physiol 305, G911–918, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00225.2013 (2013).

Ahrne, S. & Hagslatt, M. L. Effect of lactobacilli on paracellular permeability in the gut. Nutrients 3, 104–117, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu3010104 (2011).

Ahl, D. et al. Lactobacillus reuteri increases mucus thickness and ameliorates dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Acta physiologica (Oxford, England) 217, 300–310, https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.12695 (2016).

Yang, F. et al. Lactobacillus reuteri I5007 modulates tight junction protein expression in IPEC-J2 cells with LPS stimulation and in newborn piglets under normal conditions. BMC microbiology 15, 32, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-015-0372-1 (2015).

Di Luccia, B. et al. Lactobacillus gasseri SF1183 affects intestinal epithelial cell survival and growth. PloS One 8, e69102, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069102 (2013).

Wang, C. et al. Intestinal Microbiota Profiles of Healthy Pre-School and School-Age Children and Effects of Probiotic Supplementation. Ann Nutr Metab 67, 257–266, https://doi.org/10.1159/000441066 (2015).

Nagata, S. et al. The Effectiveness of Lactobacillus Beverages in Controlling Infections among the Residents of an Aged Care Facility: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Double-Blind Trial. Ann Nutr Metab 68, 51–59, https://doi.org/10.1159/000442305 (2016).

Tripolt, N. J. et al. Short communication: Effect of supplementation with Lactobacillus casei Shirota on insulin sensitivity, beta-cell function, and markers of endothelial function and inflammation in subjects with metabolic syndrome–a pilot study. J Dairy Sci 96, 89–95, https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2012-5863 (2013).

Matsuda, K., Tsuji, H., Asahara, T., Kado, Y. & Nomoto, K. Sensitive quantitative detection of commensal bacteria by rRNA-targeted reverse transcription-PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol 73, 32–39, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01224-06 (2007).

Ohigashi, S. et al. Changes of the intestinal microbiota, short chain fatty acids, and fecal pH in patients with colorectal cancer. Dig Dis Sci 58, 1717–1726, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-012-2526-4 (2013).

Fujimoto, J., Tanigawa, K., Kudo, Y., Makino, H. & Watanabe, K. Identification and quantification of viable Bifidobacterium breve strain Yakult in human faeces by using strain-specific primers and propidium monoazide. J Appl Microbiol 110, 209–217, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04873.x (2011).

Fujimoto, J., Matsuki, T., Sasamoto, M., Tomii, Y. & Watanabe, K. Identification and quantification of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota in human feces with strain-specific primers derived from randomly amplified polymorphic DNA. Int J Food Microbiol 126, 210–215, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.05.022 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank Tomomi Yoshino, Norikatsu Yuki, Yukiko Kado and Akira Takahashi for their technical assistance. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 26350871. The costs for purchasing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota-fermented milk and the analyses of blood and fecal samples related to the gut microbiota were covered by the research funds of the Probiotics Research Laboratory and the Yakult Central Institute, respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S. designed the study, participated in data collection and contributed to the discussion. A.K. designed the study, participated in data collection and wrote the manuscript. K.A., F.I., H.G., K.K., R.K. and Y.T. participated in data collection and contributed to the discussion. K.N., T.T. and T.A. designed the study, blindly measured the fecal and blood samples and edited the manuscript. Y.Y. designed the study, contributed to the discussion and edited the manuscript. H.W. contributed to the discussion and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

J.S. has received lecture fees from Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk Pharma, Sanofi and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. A.K. has received lecture fees from Kissei Pharma, Sanofi and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. Y.T. has received lecture fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, MSD, Eli Lilly, Kissei Pharma and AstraZeneca. H.W. has received lecture fees from Novo Nordisk, Inc., Eli Lilly and Company, Sanofi, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Fujifilm, Bayer Health Care, Kissei Pharmaceutical Company, Mochida Pharmaceutical Company, MSD, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Daiichi-Sankyo, Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, AstraZeneca LP, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Company, Ltd., Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusyo Company, Ltd., Kowa Company Ltd. and Astellas Pharma, Inc.; advisory fees from Novo Nordisk, Inc., Mochida Pharma Company, AstraZeneca LP, Kowa Company, Astellas Pharma, Inc., Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., MSD, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Pfizer, Inc. and Kowa Company; and research funds from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Sanofi-Aventis, Novo Nordisk Pharma, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Sanwakagaku Kenkyusho, Terumo Corp., Eli Lilly, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Daiichi Sankyo Inc., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., MSD, Shionogi, Pharma, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Kissei Pharma and Astrazeneca. K.N., T.T. and T.A. are employed by the Yakult Central Institute. K.A., F.I., H.G., K.K., R.K., and Y.Y. has nothing to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sato, J., Kanazawa, A., Azuma, K. et al. Probiotic reduces bacterial translocation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomised controlled study. Sci Rep 7, 12115 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12535-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12535-9

This article is cited by

-

Comparison of the efficacy of fish oil and probiotic supplementation on glucose and lipid metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and network meta-analysis

Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome (2024)

-

Effects of probiotic/synbiotic supplementation on body weight in patients with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized-controlled trials

BMC Endocrine Disorders (2023)

-

The effects of probiotics supplementation on glycaemic control among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials

Journal of Translational Medicine (2023)

-

Gut Microbiome and Its Impact on Obesity and Obesity-Related Disorders

Current Gastroenterology Reports (2023)

-

The role of lipopolysaccharides in diabetic retinopathy

BMC Ophthalmology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.