Abstract

Research into inexpensive ammonia synthesis has increased recently because ammonia can be used as a hydrogen carrier or as a next generation fuel which does not emit CO2. Furthermore, improving the efficiency of ammonia synthesis is necessary, because current synthesis methods emit significant amounts of CO2. To achieve these goals, catalysts that can effectively reduce the synthesis temperature and pressure, relative to those required in the Haber-Bosch process, are required. Although several catalysts and novel ammonia synthesis methods have been developed previously, expensive materials or low conversion efficiency have prevented the displacement of the Haber-Bosch process. Herein, we present novel ammonia synthesis route using a Na-melt as a catalyst. Using this route, ammonia can be synthesized using a simple process in which H2-N2 mixed gas passes through the Na-melt at 500–590 °C under atmospheric pressure. Nitrogen molecules dissociated by reaction with sodium then react with hydrogen, resulting in the formation of ammonia. Because of the high catalytic efficiency and low-cost of this molten-Na catalyst, it provides new opportunities for the inexpensive synthesis of ammonia and the utilization of ammonia as an energy carrier and next generation fuel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ammonia is an important raw material for synthesizing chemical fertilizer, and has supported worldwide food production since the development of the Haber-Bosch process1. In recent years, ammonia has also attracted attention as an energy carrier and a next generation fuel2,3,4. For instance, Hydrogen transport can be facilitated by conversion into ammonia. Furthermore, ammonia is a promising environmental friendly fuel because the combustion of ammonia does not produce CO2.

Typically, ammonia is produced using the Haber-Bosch process, which relies on an Fe-based catalyst. However, this process requires a high reaction temperature (400–600 °C) to dissociate the triple bond of nitrogen molecules (945 kJ/mol)5 and a high pressure (20–40 MPa) to suppress the decomposition of ammonia synthesized at high temperature. Maintaining high temperatures and pressures increases the production cost of ammonia and prevents its use as an energy carrier or fuel.

In 1972, a Ru-based catalyst was reported for ammonia synthesis under milder conditions than those required in the Haber-Bosch process6. Since then, Ru-based catalysts have been researched intensively7 This research has led to the development of an Ru-loaded electride catalyst8, 9 for the synthesis of ammonia. With this catalyst, the rate-limiting reaction is the formation of N-Hn species on the surface of the catalyst, rather than the decomposition of the nitrogen triple bond10.

Development of catalysts based on inexpensive elements has also been undertaken. Co3Mo3N and Co-Mo bimetal have recently been reported as effective catalysts, with activities comparable to those of Ru-based catalysts11,12,13.

The electrocatalytic synthesis of ammonia has also been researched extensively because these syntheses may be conducted under atmospheric pressure14,15,16,17,18,19. In electrocatalytic syntheses, hydrogen is ionized at an anode and the resulting protons travel through an electrolyte to react with nitrogen on a cathode to form ammonia. In addition, attempts have been made to use water at the hydrogen source for electrocatalytic ammonia synthesis20,21,22,23,24,25,26.

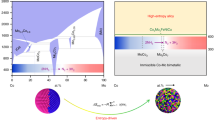

In the present study, we found that Na metal is capable of dissociating nitrogen molecules and developed an ammonia synthesis method based on bubbling H2-N2 mixed gas through a Na-melt at atmospheric pressure (Fig. 1).

Results and Discussion

Figures 2 and 3 show ion chromatograms of the collecting solution and the reaction rate of ammonia, respectively, at various temperatures. These results were based on the ammonia collected after passing 4%H2-96%N2 gas through the Na-melt at a rate of 200 sccm for 20 min.

Ion chromatograms of collecting solutions. The maximum Na+ values obtained after reactions at 500 and 530 °C are 21 and 32 μS/cm, respectively. The inset shows the ion chromatogram of the collecting solution after the experiment at 620 °C, because the maximum value of Na+ is too large to indicate with the other chromatograms.

NH4 + and Na+ were clearly detected in the collecting solutions of experiments conducted at 500–590 °C. The maximum synthetic rate of ammonia (4.17 × 10−4 μmol/s) was observed at 500 °C, and decreased with increasing temperature. NH4 + ions were not detected above 620 °C. The amount of ammonia collected was determined by the following three factors. 1) The dissociation rate of nitrogen molecules by the Na-melt. 2) The reaction rate between dissociated nitrogen and hydrogen. 3) The decomposition rate of synthesized ammonia. In the ammonia decomposition process, a significant amount of ammonia is assumed to be decomposed before reaching the collecting solution because the flow rate of the supply gas is low (200 sccm), and, therefore, synthesized ammonia remains in the heated quartz tube for a long period.

Consequently, the reaction rates shown in Fig. 3 do not represent the equilibrium values of the ammonia synthesis reaction. According to previous reports, the nitrogen dissociation ability of Na is significantly increased above 600 °C, which suggests that the decrease in the reaction rate at increasing temperature was mainly due to the decomposition of synthesized ammonia before reaching the collecting solution27.

Several studies concerning the nitrogen dissociation ability of Na have been reported. In 1994, T. L. Bush et al. reported that a silicon nitride layer could be formed on Si substrates by heating a Si substrate coated with a monolayer of either Na or K metal to 500 °C in a nitrogen atmosphere28, 29. Furthermore, GaN crystals can be synthesized in a Ga-Na mixed melt at about 800 °C by pressurizing a nitrogen atmosphere to 30 atm. In this reaction, Na functions as a catalyst for nitrogen dissociation at the gas-liquid interface27. From these reports and our experimental results, we concluded that the Na-melt dissociates nitrogen molecules to facilitate their reaction with hydrogen in the present study.

Kitano et al. reported that the materials having low work function easily decompose the nitrogen molecules, which probably be one of the reason why Na functions as catalyst for ammonia synthesis because the work function of alkaline metals are remarkably small9.

The amount of Na+ ions detected decreased with increasing temperature up to 560 °C, and then increased rapidly with increasing temperature. The presence of Na+ ions in the collecting solutions was attributed to the dissolution of NaH formed by reaction with ammonia, because evaporated Na metal was collected in the cold-trap (0 °C) before reaching the collecting solutions.

A phase diagram of NaH constructed from first principle calculations was reported in 2006, and revealed that NaH is decomposed to Na metal and H2 above 425 °C at 1 atm30. The decrease in the amount of Na+ detected from 500 to 560 °C was attributed to the reduction in the synthesis rate of NaH resulting from the increased distance from the stable region of NaH. The rapid increase in the amount of Na+ detected above 590 °C was attributed to the reaction between Na vapor originating from the Na-melt and hydrogen in the low temperature region of the apparatus. This hydrogen may either be unreacted hydrogen from the supply gas, or have been generated by decomposition of synthesized ammonia.

As a result, in the case of synthesis temperature at 560 °C, ammonia could be synthesized without formation of NaH.

The conversion efficiency of hydrogen to ammonia was low as 0.0105% at the maximum, which seems to be the result of short dwell time of bubbles in liquid and small reactive surface area. However, confirmation of ammonia synthesis at ambient pressure will give us an opportunity to improve the reacting system. We are now designing an apparatus having a mechanics that can generates H2-N2 fine-bubble in large amount of molten-Na for improving the synthesis efficiency.

In this study, we demonstrated that molten Na metal works as a catalyst for the synthesis of ammonia from hydrogen-nitrogen mixed gas. Ammonia synthesis was achieved at ambient pressure and at a relatively low temperature of about 500 °C by supplying a 4%H2-96%N2 mixed gas into an Na-melt.

Using the molten metal catalyst will open a new possibility for ammonia synthesis.

Methods

Na metal (20 g) was placed in a boron nitride (BN) vessel (inner diameter (I.D.): 22 mm, outer diameter (O.D.): 26 mm, height: 100 mm) in an Ar-purged glovebox. The BN vessel was transferred into a quartz tube (I.D.: 38 mm, O.D.: 40 mm), and connected to a flange with two nozzles for supplying and exhausting gas. The supply nozzle could be adjusted vertically. The quartz tube was set in a tubular furnace, and the supply nozzle was connected to a 4%H2-96%N2 gas cylinder. The exhaust gas was passed through a cold-trap into a collecting solution of methanesulfonic acid (1 mM).

After evacuating the quartz tube using a rotary pump, the 4%H2-96%N2 mixed gas was supplied until the inner pressure reached atmospheric pressure. The tubular furnace was heated to the desired temperature, then the supply nozzle was inserted into the molten Na metal while supplying the source gas. The source gas was supplied into the Na-melt at a flow rate of 200 sccm for 20 min, then the NH4 + ions trapped in the collecting solution were analyzed using ion chromatography. (ICS-5000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Column type: 2 mmφ × 250 mm IonPac CS14, Detector type: thermal conductivity meter). In order to prevent raising the pressure in the system, suction pump was connected at the end of exhaust tube and vacuumed at the same rate of supplied gas.

In this synthesis process, the exhaust gas is heated to the same temperature as the Na-melt, because the electric furnace heats the entirety of the quartz tube. Therefore, some of the generated ammonia decomposes, until the exhaust gasses pass through the collecting solution.

References

Erisman, J. W., Sutton, M. A., Galloway, J., Klimont, Z. & Winiwarter, W. How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world. Nat. Geosci. 1, 636–639 (2008).

Satyapal, S., Petrovic, J., Read, C., Thomas, G. & Ordaz, G. The U.S. Department of energy’s national hydrogen storage project. Progress towards meeting hydrogen-powered vehicle requirements. Catal. Today 120, 246–256 (2007).

Lan, R., Irvine, J. T. S. & Tao, S. Synthesis of ammonia directly from air and water at ambient temperature and pressure. Sci. Rep. 3, 1145 (2013).

Faehn, D., Bull, M. & Shekleton, J. Experimental investigation of ammonia as a gas turbine engine fuel. SAE Technical Papers 660769 (1966).

Gambarotta, S. & Scott, J. Multimetallic cooperative activation of N2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 5298–5308 (2004).

Aika, K., Ozaki, A. & Hori, H. Activation of nitrogen by alkali metal promoted transition metal I. Ammonia synthesis over ruthenium promoted by alkali metal. J. Catal. 27, 424–431 (1972).

Jacobsen, C. J. H. et al. Catalyst design by interpolation in the periodic table: Bimetallic ammonia synthesis catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 8404–8405 (2001).

Kitano, M. et al. Ammonia synthesis using a stable electride as an electron donor and reversible hydrogen store. Nat. Chem. 4, 934–940 (2012).

Kitano, M. et al. Essential role of hydride ion in ruthenium-based ammonia synthesis catalysts. Chem. Sci. 7, 4036–4043 (2016).

Kitano, M. et al. Electride support boosts nitrogen dissociation over ruthenium catalyst and shifts the bottleneck in ammonia synthesis. Nat. Commun. 6, 6731 (2015).

Yu, C. C., Ramanathan, S. & Oyama, S. T. New catalysts for hydroprocessing: Bimetallic Oxynitrides MI–MII–O–N (MI, MII=Mo, W, V, Nb, Cr, Mn, and Co): Part I. synthesis and characterization. J. Catal. 173, 1–9 (1998).

Kojima, R. & Aika, K. Cobalt molybdenum bimetallic nitride catalysts for ammonia synthesis. Chem. Lett. 29, 514–515 (2000).

Tsuji, Y. et al. Ammonia synthesis over Co–Mo alloy nanoparticle catalyst prepared via sodium naphthalenide-driven reduction. Chem. Commun. 52, 14369–14372 (2016).

Marnellos, G. & Stoukides, M. Ammonia synthesis at atmospheric pressure. Science 282, 98–100 (1998).

Amara, I. A., Lana, R., Petit, C. T. G., Arrighi, V. & Tao, S. Electrochemical synthesis of ammonia based on a carbonate-oxide composite electrolyte. Solid. State. Ion. 182, 133–138 (2011).

Xie, Y. H. et al. Preparation of La1.9Ca0.1Zr2O6.95 with pyrochlore structure and its application in synthesis of ammonia at atmospheric pressure. Solid State Ion 168, 117–121 (2004).

Vasileiou, E., Kyriakou, V., Garagounis, I., Vourros, A. & Stoukides, M. Ammonia synthesis at atmospheric pressure in a BaCe0.2Zr0.7Y0.1O2.9 solid electrolyte cell. Solid State Ion. 275, 110–116 (2015).

Giddey, S., Badwal, S. P. S. & Kulkarni, A. Review of electrochemical ammonia production technologies and materials. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 38, 14576–14594 (2013).

Zhang, F. et al. Proton conduction in La0.9Sr0.1Ga0.8Mg0.2O3−α ceramic prepared via microemulsion method and its application in ammonia synthesis at atmospheric pressure. Mater. Lett. 61, 4144–4148 (2007).

Kordali, V., Kyriacou, G. and Lambrou, C. Electrochemical synthesis of ammonia at atmospheric pressure and low temperature in a solid polymer electrolyte cell. Chem. Commun. 1673–1674 (2000).

Skodra, A. & Stoukides, M. Electrocatalytic synthesis of ammonia from steam and nitrogen at atmospheric pressure. Solid State Ion. 180, 1332–1336 (2009).

Lan, R., Alkhazmi, K. A., Amar, I. A. & Tao, S. Synthesis of ammonia directly from wet air using new perovskite oxide La0.8Cs0.2Fe0.8Ni0.2O3-δ as catalyst. Electrochim. Acta 123, 582–587 (2014).

Licht, S. et al. Ammonia synthesis by N2 and steam electrolysis in molten hydroxide suspensions of nanoscale Fe2O3. Science 345, 637–640 (2014).

Yun, D. S. et al. Electrochemical ammonia synthesis from steam and nitrogen using proton conducting yttrium doped barium zirconate electrolyte with silver, platinum, and lanthanum strontium cobalt ferrite electrocatalyst. J. Power Sources 284, 245–251 (2015).

Lan, R., Alkhazmi, K. A., Amar, I. A. & Tao, S. Synthesis of ammonia directly from wet air at intermediate temperature. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 152–153, 212–217 (2014).

Kosaka, F., Noda, N., Nakamura, T. & Otomo, J. In situ formation of Ru nanoparticles on La1−xSrxTiO3-based mixed conducting electrodes and their application in electrochemical synthesis of ammonia using a proton-conducting solid electrolyte. J. Mater. Sci. 52, 2825–2835 (2017).

Kawamura, F. et al. The effects of Na and some additives on nitrogen dissolution in the Ga-Na system: A growth mechanism of GaN in the Na flux method. J. Mater. Sci.-Mater. Electron. 16, 29–34 (2005).

Bush, T. L., Hayward, D. O. & Jones, T. S. The sodium promoted nitridation of Si(100)−2 × 1 using N2 molecular beams. Surf. Sci. 313, 179–187 (1994).

Bush, T. L., Hayward, D. O. & Jones, T. S. A molecular beam study of the reaction of N2 at clean and sodium covered Si(100) surfaces. Surf. Sci. 331–333, Part A, 306–310 (1995).

Caian, Q., Susanne, M. O., Gregory, B. O. & Donald, L. A. The Na-H system: from first-principles calculations to thermodynamic modeling. Int. J. Mater. Res. 97, 845–853 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Hiroshige Matsumoto (Carbon Neutral Energy International Institute, Kyushu University, Japan) for his advice during this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.K. designed and carried out the experiments. T.T. co-wrote the manuscript, discussed the results and commented on the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kawamura, F., Taniguchi, T. Synthesis of ammonia using sodium melt. Sci Rep 7, 11578 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12036-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12036-9

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.