Abstract

The West Antarctic ice sheet (WAIS) is highly vulnerable to collapsing because of increased ocean and surface temperatures. New evidence from ice core tephra shows that subglacial volcanism can breach the surface of the ice sheet and may pose a great threat to WAIS stability. Micro-CT analyses on englacial ice core tephra along with detailed shard morphology characterization and geochemical analysis suggest that two tephra layers were derived from subglacial to emergent volcanism that erupted through the WAIS. These tephra were erupted though the center of the ice sheet, deposited near WAIS Divide and preserved in the WDC06A ice core. The sources of these tephra layers were likely to be nearby subglacial volcanoes, Mt. Resnik, Mt. Thiel, and/or Mt. Casertz. A widespread increase in ice loss from WAIS could trigger positive feedback by decreasing ice mass and increasing decompression melting under the WAIS, increasing volcanism. Both tephra were erupted during the last glacial period and a widespread increase in subglacial volcanism in the future could have a considerable effect on the stability of the WAIS and resulting sea level rise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The West Antarctic ice sheet (WAIS), a large and unstable marine-based ice sheet, is highly vulnerable to accelerating ice loss caused by erosion of buttressing ice shelves by upwelling warm ocean water1 and could also be impacted by subglacial volcanic eruptions2, 3. Understanding the link between glacial cycles and volcanism has been a topic of recent research focus4,5,6,7,8,9, but much remains to be learned on this topic. The delicate balance between ice loss of the WAIS and the potential increase in volcanism, due to increased decompression melting because of ice loss4, 5 could cause a positive feedback mechanism that could increase sea level significantly in the future10. Subglacial volcanism could also produce a large amount of basal ice melt that would help lubricate the base of WAIS, causing an increase in ice flow, such has already been speculated to have occurred at Pine Island glacier in the past11.

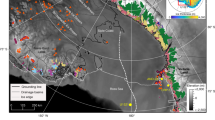

The WAIS is grounded below sea level (in some places by as much as 1200 m) whereas the East Antarctic ice sheet is largely grounded above sea level. The WAIS overlies the volcanically active West Antarctic rift system (WARS) and a number of volcanoes protrude through the ice sheet12, or are completely buried beneath the ice13 (Fig. 1). Most of the known recent volcanism in West Antarctica (Mt. Takahe and Mt. Berlin) is located near the coast. Other volcanically active areas of the WARS include the McMurdo Sound region (Mt. Erebus) and Northern Victoria Land (Mt. Melbourne and The Pleiades)12. Because the eruptive products associated with WARS extension are so inaccessible to study, it is highly likely that unrecognized active volcanism occurs at isolated points in between these larger volcanic provenances and it has been suggested that there are more than 100 subglacial volcanoes under WAIS14.

Map of Antarctica with ice cores and active volcanoes. Subglacial bedrock topography map under WAIS with locations of known or inferred subglacial volcanoes (inset). Maps were created using QGIS Version 2.14.3 (http://www.qgis.org/en/site/forusers/download.html) with bedmap2 data (https://www.bas.ac.uk/project/bedmap-2/#data)46.

Several studies using remote sensing techniques have suggested the presence of active subglacial volcanism in West Antarctica. A recent volcanic seismic swarm was observed below the Executive Committee Range2, young tephra layers have been observed using radar in the Hudson Mountains11 and an ice depression at subglacial Mt. Casertz15, where seismic activity has also been observed16 and has been interpreted to be related to subglacial volcanic activity. However, all of these studies rely on some type of remote sensing, and none were able to directly investigate the physical products of subglacial volcanism. Here, we present the first geochemical and volcanological evidence of subglacial volcanism occurring beneath WAIS obtained directly from associated tephra layers. Furthermore, X-ray micro-computed tomography (μCT) of in situ particles in ice-bound tephra layers allows a 3-dimensional view of the distribution and grain size of particles in three distinct and coarse tephra layers from the WAIS Divide ice core (WDC06A). This is the first time volcanic particles in ice have been imaged to see how particle shape and size vary with depth in the ice core, and this may prove to be a useful tool to help understand and characterize the eruptive history and tephra deposition processes. Based on geochemistry, as well as particle size and morphology, two of these layers, which have ice core ages of 22.3 and 44.8 ka (Table 1), are interpreted to be related to eruptions that probably began as subglacial events, and then breached the ice sheet surface, being deposited locally and preserved within the WAIS, then sampled by the WDC06A ice core. The third layer, in contrast, is from a subaerial volcano and shows no signs of water-magma interaction (ice core age of 32.4 ka). The presence of relatively recent subglacial volcanism in West Antarctica highlights the potential threat of West Antarctic volcanism to future ice sheet stability.

Methods

Three visible tephra layers from the WDC06A ice core, studied here, were identified by ice core handlers during initial processing of the ice core. We applied two very different, but complementary, types of analyses to these samples – scanning electron microscopy and electron microprobe analysis of particles filtered from the tephra layers, and μCT of the tephra layers preserved in ice core samples.

At New Mexico Tech, tephra from the layers was recovered by melting the ice, filtering the meltwater and then mounting the samples for imaging and quantitative analysis using the methods of Iverson, et al.17. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of tephra shards was performed using a Cameca SX100 electron microprobe. Secondary electron microscope (SEM) images were collected using an accelerating voltage of 15 kV, and a probe current of 0.5 nA. Glass analyses were carried out using a 15 kV accelerating voltage, 10 nA probe current, and defocused beam in order to avoid mobilization of Na during analysis. Details of quantitative analysis protocol can be found in Iverson, et al.17.

Ice core samples (approximately 3 × 3 × 3 cm each) containing the same tephra layers were shipped at −20 °C to the Ice Research Laboratory at the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth College, where they were stored at −30 °C until μCT analysis. Each sample was quartered (vertical cuts) to allow for triplicate sub-sampling of the ash layers. Once cut, each subsample was scanned using a Bruker Skyscan 1172 desktop μCT housed in a −10 °C cold room. The Skyscan 1172 X-ray source produces a fixed conical, polychromatic beam with a <5 μm spot size, an accelerating voltage of 60 kV and a current of 167 μA. Samples were rotated 180° in 0.7° steps, while the X-ray attenuation images were captured by an 11Mp, 12-bit cooled CCD camera fiber-optically coupled to a scintillator.

Reconstruction of the resulting radiographs was completed using a Bruker Skyscan’s NRECON® software that uses a modified Feldkamp cone-beam algorithm to produce a vertical stack of gray-scale cross-section images. The resulting images had a spatial resolution of 15 μm, and selected an internal volume of interest measuring 12 mm × 12 mm in the horizontal plane, with vertical heights varying dependent upon the thickness of the ash layer. Image post-processing was performed using a thermal drift correction of the X-ray source, ring artifact reduction, post-alignment correction, beam hardening correction, and a two-pixel Gaussian kernel smoothing to reduce noise.

A histogram shape-based approach was used to set critical thresholds, enabling us to segment the tephra particles from the gray-scale images. Particles smaller than 27 voxels (cube measuring ~45 microns on edge) were considered noise and excluded from further analysis. Individual three-dimensional analysis was performed on the resulting particles. Statistics were measured on both particle size and particle shape (i.e. sphericity, structure model index, and surface area).

Results

Visible tephra layers in ice cores typically appear as a faint dark line. In the WDC06A core, three tephra layers, Tephra A, B, and C (Table 1) are uncharacteristically thick (>1 cm). SEM characterization of particles filtered from these layers shows that they are coarse grained (average particle diameter >55 μm). Tephra B contains predominantly magmatic shards, characterized by elongate shapes and presence of vesicles (Fig. 2). Micro-CT imagry shows that large shards appear to be evenly distributed throughout the layer. In contrast, Tephra A and C appear to have a bimodal grain size distribution with most of the particles being <80 μm (blue particles in Fig. 2) and many shards >120 μm (pink and orange particles in Fig. 2). The largest and most irregular particles occur in two distinct bands (bands denoted by black arrows in Fig. 2), one at the base and the other in the upper 1/3 of the layer (Fig. 2). Many of these large fragments have mossy textures (red arrows in Fig. 2) indicative of magma-water interaction18, whereas a minority of the large shards are very fluidal, indicative of eruptions driven by magmatic volatiles, and not impacted by external water (yellow arrows in Fig. 2)19. These bands are overlain by concentrations of finer, more spherical fragments, corresponding to particles with blocky shapes. Tephra C shows a very similar distribution to Tephra A with large and irregular particles at the base with the second, less well-defined pulse of fine grained blocky particles (black arrows in Fig. 2).

In situ micro-CT sphericity and grain size analysis and SEM images of selected tephra layers from WDC06A. Top row- distribution of tephra particle sphericity based on depth in meters (A–C). Sphericity is a particle shape metric. High sphericity values are more shaped like a sphere (blocky phreatomagmatic particles). Low sphericity values are irregularly shaped particles (more vesiculated and elongated magmatic particles). Black arrows for Tephra A and C represent a change in grain size and sphericity. Middle row- grain size distribution of particles within the ice for Tephra A-C. Vertical white bars equal 1 cm in length. Two layers are considered to be phreatomagmatic (A and C) with reverse grading and several pulses of larger irregular particles and the other layer (B) is magmatic. Bottom row: SEM images of tephra A and C have bimodal particle distribution, large irregular and blocky particles (>100 μm) and small blocky shards (<50 μm). Irregular fluidal particle (yellow arrows) indicative of magmatic eruptions and blocky and mossy (red arrows) particles are typical of phreatomagmatic eruptions. Tephra B contains very large particles (>200 μm) that would be from a large Plinian eruption. White bars are equal to 100 μm.

Geochemical analyses of individual glass fragments in the tephra, by electron microprobe, show that Tephra A and C are geochemically different from typical ice-bound tephra from Marie Byrd Land volcanoes20,21,22. Tephra A is a compositionally heterogeneous tephra with glass compositions ranging from trachyandesite to trachydacite, with rare rhyolite shards (Fig. 3). Feldspars, which are rare in ice core tephra, are also found within Tephra A, and represent a compositional range (oligoclase to sanidine). Similar geochemical ranges in feldspar have been observed in the Laacher See tephra23 and may represent different batches of melt within a given eruption. Tephra C contains homogenous basanitic glass. Tephra B is a typical West Antarctica trachyte that is geochemically consistent with compositions reported for Mt. Berlin pyroclastic deposits20, 22, 24.

TAS diagram of tephra analyzed by μCT from WDC06A core. Phreatomagmatic tephra layers are blue circles (Tephra A) and green triangles (Tephra C). Black squares represent Tephra B, interpreted to be an ash fall deposit from Mt. Berlin, the dominant tephra producing volcano in West Antarctica. Orange oval represents the typical composition of ice core tephra from subaerial West Antarctic Volcanoes.

Interpretation

Tephra B contains large particles and has been geochemically correlated to the source volcano Mt. Berlin, which is 670 km from the drill site. Based on SEM observation, the morphology of many of the shards in Tephra B are distinctly magmatic, i.e. more vesiculated and less blocky than those observed in Tephra A and C. Furthermore, the composition is trachytic. Mt. Berlin is capable of producing eruption column heights 25–40 km high, which would allow for distribution of large particles over great distances22. The 92.5 ka22 eruption of Mt. Berlin deposited tephra in marine cores in the Amundsen-Bellingshausen Sea25 and East Antarctic ice cores26 over 3000 km from the eruptive source. The eruption that produced Tephra B would have been on the same order of magnitude.

The two thick coarse-grained tephra layers (A and C) are interpreted to be from local volcanoes, probably within a few hundred km from the drill site, based on the large, blocky particle size and their unique chemical composition27, 28. Neither of these coarse grained, thick tephra are found in the Byrd Core29, which is ~100 km away from the WDC06A core site, suggesting a very directional ash cloud, or one that did not travel far from source, allowing substantial deposition at WAIS and none at Byrd. The presence of these tephra layers in the Byrd Core cannot be absolutely ruled out, but, if present, the layer must have been too fine to be recognized by previous workers.

Several lines of evidence point to Tephra A and C being produced by phreatomagmatic eruptions from subglacial volcanoes nearer to the drill site. Tephra A and C have distinct grain size distributions with large mossy and fluidal particles and finer blocky fragments, observed in SEM and in μCT. The fluidal particles are characteristic of magmatic fragmentation30, whereas the mossy and blocky particles would be more typical of phreatomagmatic eruption style30, 31. In comparison, observations of many other tephra layers found in the WDC06A core are fine grained (<50 μm) and comprised mostly irregular shards 20–30 μm in diameter17. Phreatomagmatic eruptions can produce co-erupted magmatic and phreatomagmatic tephra32, but if that were the case for these tephra layers, there would be large irregular shards throughout the entire deposit. Instead, there are bands of large irregular shards mixed with smaller blocky fragment followed by band of primarily smaller blocky fragments (denoted by black arrows in Fig. 2). This repetitive sequence suggests mixed phreatomagmatic and magmatic phase followed by a more phreatomagmatic phase and finally a mixed phase. This sequence is likely caused by variations in the amount of water contacting the vent33, 34.

Although there are many variables that impact the explosivity of a given volcanic eruption, magmatic composition is a primary controlling factor, with the more evolved and/or H2O rich magmas producing higher explosivity eruptions35. Therefore, all other things being equal, the less evolved compositions of tephra layers A and C would suggest less explosive subaerial eruptions. The interaction of glacial meltwater with magma during these eruptions would have created episodic explosivity, but would not have contributed to a high, sustained eruption column36.

A phreatomagmatic genesis of Tephra layer C is further supported by the sulfur (S) concentration in the glass. Sulfur is a volatile component that fractionates into the H2O-bearing vapor phase generated during the depressurization that drives volcanic eruptions37. During the near-surface, vigorous degassing that takes place during magmatic eruptions, only small amounts of S stay in the melt, so the glass typically contains <20% of the original, pre-eruptive S content38. During phreatomagmatic eruptions, S is retained in the glass phase because fragmentation and quenching occur at a depth where S does not fully exsolve from the melt. The basanitic Tephra C, which is compositionally similar to Icelandic basalts, contains elevated and variable concentrations of S (1000–2000 ppm), which is consistent with observations made at Icelandic volcanoes that have undergone both magmatic and phreatomagmatic phases during a single eruption (Fig. 4)38. The variable S content of Tephra C, while the other major elements are invariant, suggests that fragmentation occurred at variable depths during the eruption, consistent with the interpretation of a subglacial to subaerial eruption. This tephra may have been generated from an eruption that breached the ice sheet surface, erupted explosively with some mixture of magmatic and phreatomagmatic fragmentation, switched to dominantly phreatomagmatic fragmentation, then had another pulse of mixed fragmentation once the water source was temporarily exhausted. Because Tephra A and B are more evolved and hence have lower S concentrations, S cannot be used to understand changes in fragmentation depth due to lower precision S measurements from the microprobe.

Bivariate plot of S versus TiO2/FeO to the assess phreatomagmatic origin of Tephra C. Glass fragments with higher S values are considered to have been erupted prior to degassing as in a phreatomagmatic eruption. Volcanic product best fit regression lines for melt inclusions, tephra, and lava from Icelandic basalts are from Oladottir, et al.38. Error bar for each S measurement shown in lower right.

Finding an exact analog to use to understand tephra dispersal for the eruptions that produced the two tephra layers found in the WDC06A ice core that we argue may have a begun as subglacial events, is challenging. However, two well-studied Icelandic analogs are presented here. The first is the 2004 subglacial to emergent eruption of the Grimsvotn volcano. Because the Grimsvotn eruption was basaltic, it is likely to have been somewhat less explosive than the eruptions that produced the two subglacial to emergent WDC06A tephra layers. Albedo changes in the ice cap surface, measured by MODIS, were attributed to tephra deposited on the ice sheet from the Grimsvotn eruption39. Based on this information, a tephra load of .01 g/cm2, which would represent a fine dusting of tephra, was calculated to be present 30 km from vent. At the other end of the explosivity spectrum, the 1875 rhyolitic eruption of Askja Volcano produced around 2 km3 of tephra in a series of eruptions with Plinian, subplinian, and phreatoplinian characteristics40. Based on detailed mapping, 5 mm of tephra was present 150 km from the vent, along the maximum dispersal axis for the phreatoplinian part of the event35. Given that Tephra A and C in the WDC06A core are likely to be derived from eruptions intermediate in explosivity between these two end members, it is unlikely that the deposition site sampled by the WDC06A core was no more than around 200 km from the eruptive vents. In comparison, the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull, deposition thickness of >1 cm were found only within 100 km of the edifice41 .

Three subglacial volcanoes near the WDC06A drill site have been identified by aeromagnetic surveys, and are potential sources for Tephra A and C. These are Mt. Thiel, Mt. Resnik and Mt. Casertz13. Mt. Thiel is the closest subglacial volcano to WDC06A but is 1.5 km below the ice surface. Mt. Resnik is a tall peak, with the summit only 300 m below the ice surface, <100 km away from WDC06A. However, Mt. Resnik has an overall negative magnetic signature suggesting the edifice is older than 760 ka, the last magnetic reversal13. Mt. Casertz is the only subglacial volcano with a current ice depression over the top of the edifice15. However, the volcanic peak is 1.4 km below the surface and ~250 km from WDC06A. Because there are two different tephra with distinct chemical compositions it is likely that more than one subglacial volcano has erupted through the ice sheet. All things considered, the best candidate is Mt. Resnik because of the close proximity and low ice burden. Ice sheet elevation models suggest that WAIS was >200 m lower during the last glacial period42 reducing the ice burden significantly. It is possible that recent volcanic activity at Mt. Resnik during a time of normal polarity may not be large enough to offset the overall reversed polarity of the edifice. Mt. Resnik may also be the source of both tephra but this is difficult to support without geochemical characterization of material from the Mt. Resnik edifice, which cannot be obtained without drilling.

Conclusions

Evidence from tephra layers in the WDC06A ice core suggests that two subglacial eruptions have breached the WAIS in the past 45 ka. A basanitic eruption occurred at 44.5 ka and deposited >1 cm of tephra on the local ice sheet. A second, trachyandesite to trachydacite tephra deposited 2 cm of tephra, with some shards greater than 200 μm in diameter, at 22.3 ka. Micro-CT analysis performed on these tephra show a complicated eruption history with a mixed magmatic and phreatomagmatic phase punctuating the predominantly phreatomagmatic eruptions. This is the first time that μCT has been used on in situ ice core tephra allowing for the spatial distribution of tephra particles to be observed on a scale not seen before.

Continuing ice loss from WAIS will eventually lower the ice sheet elevation and may cause a positive feedback by increasing volcanism in West Antarctic. Although there is no supporting evidence linking enhanced volcanism with collapse of WAIS in the Quaternary, increased volcanism could produce more basal melt water, increasing ice flow and ice loss thus perpetuating positive feedback. The delicate balance between deglaciation and volcanism may have a profound effect on the stability of WAIS and the subsequent sea level rise.

References

DeConto, R. M. & Pollard, D. Contribution of Antarctica to past and future sea-level rise. Nature 531, 591–597, doi:10.1038/nature17145 (2016).

Lough, A. C. et al. Seismic detection of an active subglacial magmatic complex in Marie Byrd Land, Antarctica. Nature Geoscience 6, 1031–1035, doi:10.1038/ngeo1992 (2013).

Vogel, S. W. Cryosphere: Fire and ice. Nature Geoscience 1, 91–92 (2008).

Crowley, J. W., Katz, R. F., Huybers, P., Langmuir, C. H. & Park, S.-H. Glacial cycles drive variations in the production of oceanic crust. Science 347, 1237–1240, doi:10.1126/science.1261508 (2015).

Rawson, H. et al. The magmatic and eruptive response of arc volcanoes to deglaciation: Insights from southern Chile. Geology 44, 251–254, doi:10.1130/G37504.1 (2016).

Tolstoy, M. Mid-ocean ridge eruptions as a climate valve. Geophysical Research Letters 42, 1346–1351, doi:10.1002/2014GL063015 (2015).

Watt, S. F. L., Pyle, D. & Mather, T. The volcanic response to deglaciation: evidence from glaciated volcanic arcs and a reassessment of global eruption records. Earth-Science Reviews 122, 77–102 (2013).

Maclennan, J., Jull, M., McKenzie, D., Slater, L. & Grönvold, K. The link between volcanism and deglaciation in Iceland. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 3, 1–25, doi:10.1029/2001GC000282 (2002).

Huybers, P. & Langmuir, C. Feedback between deglaciation, volcanism, and atmospheric CO2. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 286, 479–491 (2009).

Feldmann, J. & Levermann, A. Collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet after local destabilization of the Amundsen Basin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 14191–14196 (2015).

Corr, H. F. J. & Vaughan, D. G. A recent volcanic eruption beneath the West Antarctic ice sheet. Nature Geoscience 1, 122–125, doi:10.1038/ngeo106 (2008).

LeMasurier, W. E. & Thomson, J. W. Volcanoes of the Antarctic Plate and Southern Ocean. American Geophysical Union- Antarctic Research Series 48, 1–487 (1990).

Behrendt, J. C. The aeromagnetic method as a tool to identify Cenozoic magmatism in the West Antarctic Rift System beneath the West Antarctic Ice Sheet - A review; Thiel subglacial volcano as possible source of the ash layer in the WAISCORE. Tectonophysics 585, 124–136, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2012.06.035 (2013).

de Vries, M. v. W., Bingham, R. G. & Hein, A. S. A new volcanic province: an inventory of subglacial volcanoes in West Antarctica. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 461, SP461. 467 (2017).

Blankenship, D. D. et al. Active volcanism beneath the West Antarctic ice sheet and implications for ice-sheet stability. Nature 361, 526–529 (1993).

Winberry, J. P. & Anandakrishnan, S. Seismicity and neotectonics of West Antarctica. Geophysical Research Letters 30, doi:10.1029/2003GL018001 (2003).

Iverson, N. A., Kalteyer, D., Dunbar, N. W., Kurbatov, A. & Yates, M. Advancements and best practices for analysis and correlation of tephra and cryptotephra in ice. Quaternary Geochronology 40, 45–55, doi:10.1016/j.quageo.2016.09.008 (2017).

Sheridan, M. F. & Marshall, J. R. Interpretation of pyroclast surface-features using SEM images. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 16, 153–159, doi:10.1016/0377-0273(83)90088-4 (1983).

Heiken, G. & Wohletz, K. H. Volcanic Ash. University of California Press, Berkeley (1985).

Dunbar, N. W., McIntosh, W. C. & Esser, R. P. Physical setting and tephrochronology of the summit caldera ice record at Mount Moulton, West Antarctica. Geological Society of America Bulletin 120, 796–812, doi:10.1130/b26140.1 (2008).

Dunbar, N. W., Zielinski, G. A. & Voisins, D. T. Tephra layers in the Siple Dome and Taylor Dome ice cores, Antarctica: Sources and correlations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 108, 2374, doi:10.1029/2002JB002056 (2003).

Wilch, T. I., McIntosh, W. C. & Dunbar, N. W. Late Quaternary volcanic activity in Marie Byrd Land: Potential40Ar/39Ar-dated time horizons in West Antarctic ice and marine cores. Geological Society of America Bulletin 111, 1563–1580, doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1999)111<1563:lqvaim>2.3.co;2 (1999).

Wörner, G. & Schmincke, H.-U. Mineralogical and chemical zonation of the Laacher See tephra sequence (East Eifel, W. Germany). Journal of Petrology 25, 805–835 (1984).

Dunbar, N. W. Tephra layers in the Siple Dome and Taylor Dome ice cores, Antarctica: Sources and correlations. Journal of Geophysical Research 108, doi:10.1029/2002jb002056 (2003).

Hillenbrand, C. D. et al. Volcanic time-markers for Marine Isotopic Stages 6 and 5 in Southern Ocean sediments and Antarctic ice cores: implications for tephra correlations between palaeoclimatic records. Quaternary Science Reviews 27, 518–540, doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.11.009 (2008).

Narcisi, B., Robert Petit, J. & Tiepolo, M. A volcanic marker (92ka) for dating deep east Antarctic ice cores. Quaternary Science Reviews 25, 2682–2687, doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.07.009 (2006).

Durant, A. J. et al. Long-range volcanic ash transport and fallout during the 2008 eruption of Chaitén volcano, Chile. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C 45, 50–64, doi:10.1016/j.pce.2011.09.004 (2012).

Stevenson, J. A., Millington, S. C., Beckett, F. M., Swindles, G. T. & Thordarson, T. Big grains go far: understanding the discrepancy between tephrochronology and satellite infrared measurements of volcanic ash. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 8, 2069–2091, doi:10.5194/amt-8-2069-2015 (2015).

Palais, J. M. & Kyle, P. R. Chemical composition of ice containing tephra layer in the Byrd Station ice core, Antarctica. Quaternary Research 30, 315–330, doi:10.1016/0033-5894(88)90007-5 (1988).

Buttner, R., Dellino, P., La Volpe, L., Lorenz, V. & Zimanowski, B. Thermohydraulic explosions in phreatomagmatic eruptions as evidenced by the comparison between pyroclasts and products from Molten Fuel Coolant Interaction experiments. Journal of Geophysical Research-Solid Earth 107, doi:10.1029/2001jb000511 (2002).

Sheridan, M. F., Wohletz, K. H. & Dehn, J. Discrimination of grain-size subpopulations in pyroclastic deposits. Geology 15, 367, doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1987)15<367:dogsip>2.0.co;2 (1987).

Clarke, H., Troll, V. R. & Carracedo, J. C. Phreatomagmatic to Strombolian eruptive activity of basaltic cinder cones: Montana Los Erales, Tenerife, Canary Islands. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 180, 225–245, doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2008.11.014 (2009).

Jude-Eton, T. C., Thordarson, T., Gudmundsson, M. T. & Oddsson, B. Dynamics, stratigraphy and proximal dispersal of supraglacial tephra during the ice-confined 2004 eruption at Grímsvötn Volcano, Iceland. Bulletin of Volcanology 74, 1057–1082, doi:10.1007/s00445-012-0583-3 (2012).

Cioni, R. et al. Insights into the dynamics and evolution of the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull summit eruption (Iceland) provided by volcanic ash textures. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 394, 111–123, doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2014.02.051 (2014).

Papale, P., Neri, A. & Macedonio, G. The role of magma composition and water content in explosive eruptions: 1. Conduit ascent dynamics. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 87, 75–93 (1998).

Edwards, B. R., Gudmundsson, M. T. & Russell, J. K. In The Encyclopedia of Volcanoes (Second Edition) 377–393 (Academic Press, 2015).

Métrich, N. & Wallace, P. J. Volatile Abundances in Basaltic Magmas and Their Degassing Paths Tracked by Melt Inclusions. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 69, 363–402, doi:10.2138/rmg.2008.69.10 (2008).

Oladottir, B. A., Thordarson, T., Larsen, G. & Sigmarsson, O. Survival of the Mýrdalsjökull ice cap through the Holocene thermal maximum: evidence from sulphur contents in Katla tephra layers (Iceland) from the last ∼8400 years. Annals of Glaciology 45, 183–188, doi:10.3189/172756407782282516 (2007).

Möller, R. et al. MODIS-derived albedo changes of Vatnajökull (Iceland) due to tephra deposition from the 2004 Grímsvötn eruption. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 26, 256–269, doi:10.1016/j.jag.2013.08.005 (2014).

Carey, R., Houghton, B. & Thordarson, T. Tephra dispersal and eruption dynamics of wet and dry phases of the 1875 eruption of Askja Volcano, Iceland. Bulletin of Volcanology 72, 259–278 (2010).

Gudmundsson, M. T. et al. Ash generation and distribution from the April-May 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull. Iceland. 2, 572, doi:10.1038/srep00572 (2012).

Steig, E. J. et al. West Antarctic ice sheet elevation changes, The West Antarctic Ice Sheet: Behavior and Environment, AGU-Antarctic Research Series. 77, 75–90 (2001).

Sigl, M. et al. The WAIS Divide deep ice core WD2014 chronology–Part 2: Annual-layer counting (0–31 ka BP). Clim. Past 12, 769–786, doi:10.5194/cp-12-769-2016 (2016).

Buizert, C. et al. The WAIS Divide deep ice core WD2014 chronology - Part 1: Methane synchronization (68-31 kaBP) and the gas age-ice age difference. Climate of the Past 11, 153–173, doi:10.5194/cp-11-153-2015 (2015).

Iacovino, K. Glass Density Calc v 3.0 [Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet], 2014).

Fretwell, P. et al. Bedmap2: improved ice bed, surface and thickness datasets for Antarctica. The Cryosphere 7, 375–393, doi:10.5194/tc-7-375-2013 (2013).

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by the NSF Division of Polar Programs through Grants PLR-1142115, 1142069 to New Mexico Tech and ANT-1142035 to Dartmouth College. The authors greatly appreciate the support of the WAIS Divide Science Coordination Office at the Desert Research Institute, Reno, NE, USA and University of New Hampshire, USA, for the collection and distribution of the WAIS Divide ice core and related tasks (NSF Grants 0230396, 0440817, 0944348; and 0944266). Thanks to Kendrick Taylor for leading the field effort that collected the ice core. The National Science Foundation Division of Polar Programs also funded the Ice Drilling Program Office (IDPO) and Ice Drilling Design and Operations (IDDO) group for coring activities; the National Ice Core Laboratory for curation of the ice core and assistance in sampling; the Antarctic Support Contractor for logistics support in Antarctica; and the 109th New York Air National Guard for airlift in Antarctica. Bill McIntosh’s guidance and comments helped immensely on early drafts of the manuscript. Thanks to John Smellie and an anonymous reviewer for their thoughtful comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All of the authors contributed to the design and constructing of the manuscript in various capacities and they are briefly discussed below. The manuscript was prepared as a collaboration between New Mexico Tech and Dartmouth College. Dunbar and Obbard were responsible for conceptualizing and designing the project and provided funding for project. The majority of the manuscript and figures were prepared and written by Iverson. Lieb-Lappen wrote the Micro-CT methods sections and also prepared all of the Micro-CT images found in Fig. 2 as well as the Micro-CT supplemental data. Dunbar was the primary editor of the manuscript and made several contributions to the collection of geochemical data and rewriting of the manuscript. Obbard oversaw the Micro-CT work done by her students (Lieb-Lappen, Kim and Golden) and provided help for interpreting the Micro-CT imagery and results. Obbard also provided significant edits that greatly improved the manuscript. Kim and Golden were responsible for preparing and collecting Micro-CT samples. They were also responsible for the data analysis and interpretations for all of the Micro-CT samples. The Micro-CT work was part of their senior thesis projects.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iverson, N.A., Lieb-Lappen, R., Dunbar, N.W. et al. The first physical evidence of subglacial volcanism under the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Sci Rep 7, 11457 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11515-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11515-3

This article is cited by

-

Lithofacies and eruptive conditions of the southernmost volcanoes in the world (87° S)

Bulletin of Volcanology (2021)

-

Evidence of an active volcanic heat source beneath the Pine Island Glacier

Nature Communications (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.