Abstract

Guanosine monophosphate, among the nucleotides, has the unique property to self-associate and form nanoscale cylinders consisting of hydrogen-bonded G-quartet disks, which are stacked on top of one another. Such self-assemblies describe not only the basic structural motif of G-quadruplexes formed by, e.g., telomeric DNA sequences, but are also interesting targets for supramolecular chemistry and nanotechnology. The G-quartet stacks serve as an excellent model to understand the fundamentals of their molecular self-association and to unveil their application spectrum. However, the thermodynamic stability of such self-assemblies over an extended temperature and pressure range is largely unexplored. Here, we report a combined FTIR and NMR study on the temperature and pressure stability of G-quartet stacks formed by disodium guanosine 5′-monophosphate (Na25′-GMP). We found that under abyssal conditions, where temperatures as low as 5 °C and pressures up to 1 kbar are reached, the self-association of Na25′-GMP is most favoured. Beyond those conditions, the G-quartet stacks dissociate laterally into monomer stacks without significantly changing the longitudinal dimension. Among the tested alkali cations, K+ is the most efficient one to elevate the temperature as well as the pressure limits of GMP self-assembly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery in 1953 of the right-handed double helical structure and the Watson-Crick base pairs of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) gave birth to modern molecular biology1,2,3. However, in recent years it has become evident that DNA can also adopt a variety of non-canonical conformations in vivo including G-quadruplex structures4, which are thought to be functionally crucial for genome integrity and stability. G-quadruplex structures have emerged to be substantial nucleic acid based control and sensing elements involved in regulating and altering transcription, replication, translation and genome stability5,6,7,8,9. Targeting G-quadruplexes in gene promotors has also drawn attention in anticancer strategies7, 10. Potential G-quadruplex sequences are highly conserved and have been demonstrated to exist throughout the functional parts of prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes suggesting importance in biological evolution5, 7. They are formed in G-rich regions of DNA or RNA sequences. However, there are fundamental differences between RNA and DNA G-quadruplexes. The additional 2′-hydroxyl-group in the ribose sugar causes greater hydration and enhanced stability of the RNA variant6, 11. However, a very recent study pointed out that the formation of RNA G-quadruplexes is overwhelmingly prevented in eukaryotic cells, whereas the same sequences ectopically expressed in Escherichia coli fold into the G-quadruplex conformation, suggesting the presence of a very effective molecular machinery in eukaryotes to maintain such structures in the unfolded state12. Similarly, the formation of DNA G-quadruplexes in heterochromatin is also suppressed, whereas G-quadruplexes can be found in nucleosome-depleted regions and their formation is associated with increased transcriptional activity13. The structural topology of G-quadruplexes is highly polymorphic and depends on the number, orientation and loop structure of the G-rich chains during G-quadruplex folding14. Despite their structural polymorphism, they share the common feature of forming cyclic, planar and hydrogen-bonded guanine tetramers known as the G-quartets which are stacked on top of one another forming a right-handed four-stranded helical structure. In the helix, adjacent G-quartets are twisted by 30° and separated by 3.4 Å15,16,17. The G-quadruplex structure is stabilized by monovalent cations which are sandwiched between the G-quartets in the central cavity coordinating the eight guanine O6 atoms18,19,20,21,22,23. However, in case of the smallest alkali cation Na+, it can exist in- or out-of-plane and move in and out of the octamer up to 108 times per second20, 23,24,25. Those cation-dipole interactions stabilize the self-complementary hydrogen bonds of guanine and the base stacking interactions along the helix. The cation not only defines the stability of G-quadruplex structures, but also plays an important role in modulating their structural polymorphism26, 27.

Interestingly, since the early 1960s, long before the existence of telomeres and their G-quadruplex structures had been shown17, 28, the unique ability of guanosine 5′-monophosphate (5′-GMP) to undergo self-association, thereby forming right-handed helices with G-quartets stacking along the helix axis, was already known15, 25, 29. The propensity of self-assembly and the size of aggregates depend on the sample concentration, solution acidity and presence of alkali cations25, 29,30,31,32. At acidic pH, the self-association of 5′-GMP can even lead to the formation of anisotropic gels33. A recent NMR study revealed that three types of stacked 5′-GMP aggregates can generally coexist upon self-assembly using monomers, dimers and G-quartets as building blocks (Fig. 1a)34. The monomeric and dimeric species undergo exchange on the ms time scale, whereas the tetrameric species are rather kinetically stable30, 34. The size of the self-aggregates has been shown to be on the nanometer scale corresponding to tens of quartets per stack31, 32, 35. The 5′-GMP quartets are stacked in a head-to-tail manner with alternating C2′-endo and C3′-endo sugar puckers along the helical strand forming a chiral cylinder34. The alternating sugar conformations allow further stabilization of the helix via P-O−···H-O2/3′ hydrogen bonds along the helical strand which are reminiscent of the phosphodiester bonds in DNA or RNA34. Self-assembly of 5′-GMP is not only determined by Hoogsteen-like base pairing, π-π interaction, the hydrophobic effect and thus release of water, but also by cation binding36. The cation-templated self-association requires two different cation binding sites, namely the surface and channel site37, 38. The adjacent peripheral phosphate groups are separated by 6.7 Å allowing true ionic binding of a sodium cation to bridge and to partially neutralize the electrostatic repulsion of the two doubly negatively charged groups34, 37. In contrast, due to steric reasons, potassium and rubidium cations have been shown to undergo only counterion condensation to screen the charge density of the phosphate groups37. Consistently, the order of cation binding affinity for the surface site has been found to be Na+ > Rb+ > K+ 38. However, the stability of the G-quartet stacks is predominantly determined by the cation type located in the central channel of the helix. The eight inwardly pointing guanine O6 atoms of two adjacent G-quartets span a volume of ca. 40 Å3 serving as the channel binding site which has an affinity order of K+ > Rb+ > Na+ 19, 37,38,39,40. Ab initio calculations showed that the cation-dipole interaction provides more stabilization than either hydrogen bonding or stacking interaction and diminishes the electrostatic repulsion between the tightly packed cations41, 42. For a long time, the cation selectivity of the channel site was explained by the concept of optimal fit18, 43. Compared to the smaller Na+ and the larger Rb+, K+ ions were thought to have the optimal size to fit into the central cavity of the G-quartet helix. However, the mechanism of size-selective coordination does not consider the dehydration process of the cation before entering the cavity and the associated free energy cost which has to be balanced by the free energy of the cation-guanine interaction44,45,46. NMR studies and ab initio calculations have revealed that the free energy of the cation-guanine interaction follows the trend in charge density of the alkali cations, but the preferred coordination of K+ over Na+ originates from their relative free energies of hydration38, 45, 46. Therefore, the cation affinity for the channel site is controlled by the balance of the free energy cost and gain of cation dehydration and binding, respectively.

Concentration-dependent self-assembly of disodium 5′-guanosine monophosphate (Na25′-GMP) at pH 8. (a) Schematic structure of 5′-GMP monomer, dimer and G-quartets. For clarity, only the chemical structure of the guanine base is shown. The cation M+ can be in-plane or out-of-plane of the G-quartet. (b) Area normalized FTIR spectra of Na25′-GMP in D2O at different concentrations: (i) in the range of 1700–1640 cm−1 (C=O stretch vibration), and (ii) in the range of 1600–1520 cm−1 at 282 K (C=N and C=C ring vibration). Arrows indicate the absorbance change upon self-assembly. (c) DLS diagrams of Na25′-GMP in H2O at different concentrations and 282 K. Hydrodynamic diameters calculated based on spherical symmetric particles and using the method of cumulants. Error bars indicate mean ± s.d. of three scans. (d) 1H NMR spectrum of the H8 region and (e) the corresponding population distribution for 0.48 M Na25′-GMP at 278 K.

Due to its simplicity, the non-covalent self-association of 5′-GMP has drawn unabated attention since its discovery and has become an essential model in many areas including structural biology, medicinal chemistry, supramolecular chemistry and nanotechnology25. The G-quartet structures show promise as a scaffold for synthetic ion channels, but also as components in nanotechnology including nanowires, nanomachines, biosensors, and molecular electronic devices25. Moreover, in origin-of-life studies, particularly in those where a protein-free RNA world scenario is assumed47, 48, the self-assembly of GMP could have served as a platform for prebiotic coalescence of nucleotides37, 49, 50. Interestingly, today densely packed guanine crystals can be found in the retinal pigment epithelium of deep-sea fishes focusing light to the photoreceptors51. As a popular model for numerous disciplines, the thermodynamic stability of GMP self-assemblies is still largely unexplored, however. Here, we present a comprehensive study to reveal the temperature- and pressure-dependent stability of G-quartet stacks formed by 5′-GMP in the presence of the alkali cations Na+, K+ and Rb+. Using a series of scattering and spectroscopic methods, we show that under abyssal conditions, where temperatures as low as 5 °C and pressures up to 1 kbar are reached, the self-association of Na25′-GMP is most favoured. Beyond those conditions, the G-quartet stacks dissociate laterally into monomer stacks without changing the longitudinal dimension. Hydration, stacking interaction and packing defects play important roles in determining the stability of such supramolecular structures. In the presence of the alkali cations K+ and Rb+, which bind and replace the Na+ cation from the channel cavity of the G-quartet stacks, the temperature and pressure stability of the 5′-GMP quartets is significantly increased.

Results and Discussions

Concentration-dependent self-assembly

In the planar G-quartets, hydrogen bonds are formed between N1-H and N2-H as H-donors and O6 and N7 as H-acceptors, whereas dimer formation is based on hydrogen bonds between N1 and O6 (Fig. 1a). Hence, significant shifts and absorbance changes of infrared (IR) bands in the region of 1700–1500 cm−1 characteristic of the guanine base can be observed upon 5′-GMP self-assembly52. Figure 1b displays concentration-dependent Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of Na25′-GMP at pH 8. The band at \({\tilde{v}}_{max}\) = 1657 cm−1 has been assigned to the C6=O6 stretch vibration of guanine. Upon 5′-GMP self-association, the carbonyl band is blue shifted to \({\tilde{v}}_{max}\) = 1673 cm−1 and becomes sharper. Simultaneously, the ring vibrations of guanine including C=C and C=N stretch vibration are also affected by base pairing and stacking of 5′-GMP, i.e., an intensity increase of the bands at \({\tilde{v}}_{max}\) = 1592 cm−1 and 1537 cm−1 as well as an intensity decrease of the bands at \({\tilde{v}}_{max}\) = 1582 cm−1 and 1568 cm−1. Further, we followed the self-assembly of Na25′-GMP via dynamic light scattering (DLS) and obtained qualitative information about the size distribution of 5′-GMP aggregates (Fig. 1c). The cylinder diameter of monomeric and tetrameric 5′-GMP aggregates are approximately 1 and 2.6 nm, respectively32. The length of the cylinder is defined by (n − 1) × 0.34 nm, where n is the number of quartets in the stack. At a concentration of 0.12 M and pH 8, our FTIR and DLS data indicate that Na25′-GMP does not form stacks of dimers or quartets, but non-hydrogen-bonded aggregates, thus very likely monomeric stacks are present only. These findings are in agreement with literature data32. Starting from 0.24 M, initial formation of larger hydrogen-bonded 5′-GMP assembled species can be observed. They coexist with the monomeric stacks and their presence increases with the concentration of Na25′-GMP (Fig. 1a and c). To further characterize those assemblies, we applied 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Upon self-association of 5′-GMP, ring-current and electrostatic effects induce upfield and downfield shifts of the H8 signal30. The four peaks of the H8 region located between 7.1 and 8.6 ppm of the 1H NMR spectrum have been assigned to monomeric, dimeric and tetrameric species of 5′-GMP (Fig. 1d)34, 53. The “outer” peaks at 8.5 and 7.2 ppm (Hα and Hδ) with equal intensities are attributed to tetrameric 5′-GMP with either a C2′-endo or a C3′-endo sugar pucker conformation. The Hγ peak at 7.9 ppm indicates monomeric 5′-GMP, whereas the Hβ peak at 8.2 ppm corresponds to dimeric 5′-GMP. By integrating the H8 signals, we could quantify the population distribution for the self-assembly of Na25′-GMP (Fig. 1e). At a concentration of 0.48 M, more than 50% of the 5′-GMP molecules participate in forming G-quartet stacks. Only about 22% of the nucleotides are in the short-lived dimeric state34. Previous NMR diffusion experiments have revealed that the number of stacks increases with the nucleotide concentration32. Thereby, Wong et al. found the mechanism of stacking to be the same for monomers and G-quartets32. Hence, the channel cation in G-quartet stacks might be less needed for stacking, but rather to neutralize the electrostatic repulsion of the O6 atoms of the G-quartets. Furthermore, we found the concentration dependence of the Na25′-GMP self-assembly to be affected by temperature (Suppl. Fig. S1), in good agreement with literature data32. While initial hydrogen-bonded self-assembly is observable at 0.24 M Na25′-GMP and 282 K, the critical concentration is increased to 0.48 M at 296 K, indicating high entropic costs for the self-association.

Thermal Stability of 5′-GMP self-assemblies

Previous NMR diffusion experiments have demonstrated that the stacking behaviour of G-quartets and thus the length of the stacks are not modulated by temperature in the range between 278 and 298 K32. To yield information about the thermal stability of the hydrogen bonds formed in dimers and G-quartets of 5′-GMP, we performed temperature-dependent FTIR measurements for 0.48 M Na25′-GMP at pH 8 (Fig. 2). IR spectra of both the carbonyl band and the ring vibrations change markedly with increasing temperature, indicating dissociation of the dimers and G-quartets (Fig. 2a). Upon temperature increase, the carbonyl band shifts from 1673 to 1657 cm−1 and broadens. In the case of the ring vibrations, the band intensities at 1592 and 1537 cm−1 decrease at elevated temperatures, whereas the bands at 1582 and 1568 cm−1 show increased intensities and slight red shifts. To better describe the “melting” behaviour, we plotted the band intensities at 1673, 1592, 1568 and 1537 cm−1 as a function of temperature (Fig. 2b). The “melting” curves follow the same course, indicating that any of those bands can be used to follow the self-association of 5′-GMP. Assuming an apparent thermodynamic equilibrium between all the hydrogen-bonded and the monomer stacks, a global Boltzmann fit of the IR data was performed. We obtained a melting temperature of T m = 281 ± 2 K and a standard-state van’t Hoff enthalpy change of \({\rm{\Delta }}{H}_{{\rm{vH}}}^{{\rm{0}}}\) = 124 ± 8 kJ mol−1 for the dissociation reaction of Na25′-GMP. In this thermodynamic model, the contribution of 5′-GMP monomers not participating in the self-association reaction, are not considered in the initial plateau values. Using 1H NMR, we obtained comparable trends by analyzing the temperature-dependent population distribution of the monomer, dimer and G-quartet species (Fig. 2c). Although ab initio calculations have assigned the Watson-Crick faced guanine dimer (GG32) to be the most stable homo base pair54, it is less thermally stable compared to the cation-templated G-quartet. Furthermore, our temperature-dependent DLS measurements suggest that temperatures up to 348 K induce only the dissociation of hydrogen bonds and do not affect the stacking behaviour (Suppl. Fig. S2). The hydrodynamic size of the monomer stacks is hardly changed by the temperature. Taken together, our data reveal that the stacking interaction involved in 5′-GMP self-assembly can withstand a wide range of temperatures, whereas the base pairs are only stable at low temperatures. In an entropy-centered view, the favourable stacking interactions at high temperature can be explained by the hydrophobic effect and thus an entropy gain due to water release, whereas the G-quartet formation is accompanied by conformational entropy loss and thus becomes unfavourable with increasing temperature.

Temperature dependence of 5′-GMP self-assembly. (a) Area normalized FTIR spectra of 0.48 M Na25′-GMP in D2O as a function of temperature for (i) the C=O stretch vibration, and (ii) the ring vibrations (C=C, C=N), with (iii-iv) the corresponding difference spectra. The absorption spectrum at 274 K was subtracted for the spectra at high temperatures. (b) Absorbance intensities at the given wavenumbers as a function of temperature. The lines indicate a global Boltzmann fit to the experimental data. (c) Population distribution of 0.48 M Na25′-GMP at different temperatures obtained from 1H NMR. Green: G-quartet, orange: dimer, black: monomer.

Effect of pressure on 5′-GMP self-assembly

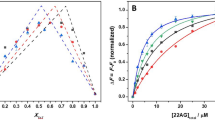

Pressure acts on molecular systems through changes in specific volume that are due to changes in hydration and packing efficiency55. According to Le Châtelier’s principle, conformations occupying smaller volumes and processes for which the transition state has a smaller volume than the ground state are favoured under high pressure conditions56. In the case of proteins, pressure favours conformations that minimize solvent-excluded void volume and causes water filling of hydrophobic cavities/voids. Furthermore, pressure leads to greater hydration of polar/charged amino acids, resulting in attenuation of ionic interactions56. Therefore, pressure is particularly sensitive to changes in hydration as the density of hydration water around charged residues is higher than that of bulk water57. Interestingly, conformations and configurations of DNA duplexes have been demonstrated to be relatively unaffected by pressure perturbation58,59,60,61, whereas an intramolecular, antiparallel DNA G-quadruplex structure has been reported to be more pressure-sensitive62. To study the pressure effect on the self-assembly of 5′-GMP, we first applied pressure-dependent FTIR measurements at various temperatures (Fig. 3). Upon pressurization, a blue shift of the IR bands is observable and can be explained by the pressure-induced compression of the bond lengths (Figs 3a and S3)63. Due to this intrinsic elastic pressure effect on the vibrational frequency, we decided to consider the IR band at ~1537 cm−1 for further analysis and plotted the absorbance intensity of the band maximum as a function of pressure (Fig. 3b). Again, we obtained an intensity decrease suggesting pressure-induced dissociation of the hydrogen-bonded species. However, the pressure-induced disassembly is less pronounced compared to the thermal-induced dissociation. At 278 K, dissociation could not be completed upon pressurization up to 1200 MPa. When the thermal disassembly is nearly complete at 308 K, no further pressure-induced assembly or disassembly of G-quartets is observable. Complementary high pressure 1H NMR measurements confirm that pressure populates the monomeric state (Figs 4 and S4). Upon pressurization up to 240 MPa, the tetrameric fraction is reduced from 56% to 26%, whereas the dimeric fraction diminishes from 22% to 11%, indicating that the G-quartets and the rather thermally unstable dimers feature similar pressure stabilities (Fig. 4b). The standard-state free energy change for the disassembly process of 5′-GMP, \({\rm{\Delta }}{G}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{0}}}\), was calculated from the mole fractions of monomeric and hydrogen-bonded species and plotted as a function of pressure (Fig. 4c). The pressure-dependence of \({\rm{\Delta }}{G}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{0}}}\) describes the standard molar volume change for the disassembly process of 5′-GMP, \({\rm{\Delta }}{V}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{0}}}\). We obtained \({\rm{\Delta }}{V}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{0}}}\) = −18 mL mol−1 at 278 K. The corresponding transition pressure value, p m, is 164 MPa (at \({\rm{\Delta }}{G}_{{\rm{D}}}^{0}({p}_{{\rm{m}}})\) = 0). \({\rm{\Delta }}{V}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{0}}}\) increases, whereas p m decreases with elevated temperature (Suppl. Fig. S4). To address the question whether the length of the stacks and thus the stacking interaction is affected by pressure, we performed pressure-dependent small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and diffusion-ordered NMR spectroscopy (DOSY). Owing to the high polydispersity within the system, as stacks of monomers, dimers and G-quartets are present in equilibrium, the SAXS data are interpreted in a qualitative manner, only. The overall high intensities of the scattering profile indicate the existence of large species (Fig. 5a). Upon pressurization, a slight decrease of the scattering intensity can be observed at 280 K, whereas the scattering profile at 308 K is marginally changed with pressure, suggesting that the longitudinal dimension of the monomer stacks is hardly affected by pressure. Complementary 1H DOSY NMR experiments yielded the molecular translational diffusion coefficients, D t, of stacks formed by 5′-GMP monomers and G-quartets as a function of pressure (Fig. 5b). The D t values reveal that the stacking interaction and thus the longitudinal dimension of the G-quartet stacks are pressure-resistant up to about 240 MPa, independent of temperature. In contrast, at low temperature the number of stacks for 5′-GMP monomers is even increased with pressure, indicating dense packing of such assemblies.

Pressure dependence of 5′-GMP self-assembly. (a) Area normalized FTIR spectra of 0.48 M Na25′-GMP in D2O and at 288 K as a function of pressure for (i) the C=O stretch vibration, and (ii) the ring vibrations (C=C, C=N). (b) Absorbance intensities of the IR band at ~1537 cm−1 as a function of pressure upon area normalization.

High pressure 1H NMR of 5′-GMP self-assembly at 278 K. (a) Stack plot of the 1H NMR spectra for 0.48 M Na25′-GMP as a function of pressure. (b) Pressure-dependent population distribution of 5′-GMP. (c) Pressure-dependent standard free energy of the 5′-GMP disassembly. The dashed line is the least-square fit to the data and describes the standard molar volume change of the dissociation process.

Effect of pressure on the size of 5′-GMP aggregates. (a) SAXS intensity profiles of 0.48 M Na25′-GMP in H2O as a function of pressure. (b) Viscosity corrected translational diffusion coefficients, D t·η, of 5′-GMP monomer and G-quartet stacks as a function of pressure obtained from 1H DOSY NMR. (c) Tentative illustration of the dissociation process of 5′-GMP self-assemblies induced by temperature and pressure. Of note, the morphology of the monomeric stacks/aggregates is not known.

Overall, our results show that pressure increases base stacking and induces lateral dissociation of dimer and G-quartet stacks of 5′-GMP into monomer stacks (Fig. 5c). In general, high pressure studies on DNA duplexes have revealed that pressure decreases the extent of charge neutralization by cations, reduces the Watson-Crick hydrogen-bond distance and favours base stacking, but leads to a very small net effect on the stability and conformation58, 59, 64. The attenuation of electrostatic interactions is explained by greater hydration of the cations and the phosphate groups under high-pressure conditions (electrostrictive effect). Consequently, the electrostatic repulsion between adjacent, negatively charged phosphates is also decreased, favouring stacking of neighbouring bases64, 65. Stacking of aromatic compounds has been shown to be accompanied by a negative volume change and is thus favoured at elevated pressures66. In case of the 5′-GMP self-assembly, the observed pressure resistance of the longitudinal dimension and thus the stacking interaction can be explained by the same mechanism. In the liquid-crystalline phase, where the 5′-GMP quartet stacks are hexagonally arranged, the stacking distance has been shown to be decreased upon compression67. Further, an acidic shift of the water pH upon pressurization would lead to partial protonation of the doubly charged phosphate groups, thus reducing the electrostatic repulsion between adjacent guanine bases68. In contrast, the typical pressure-induced strengthening of hydrogen bonds does not lead to a stabilization of the G-quartet structure, but rather a dissociation at elevated pressures. This finding suggests a volume increase upon G-quartet formation, which is unfavourable under high pressure conditions. The distance between the diagonal O6 atoms in the G-quartet is approximately 5 Å and the eight inwardly pointing guanine O6 atoms of two adjacent G-quartets span a volume of 40 Å3 38. The Na+ ion has a diameter of 1.9 Å and a volume of 3.6 Å3. As the central channel formed by G-quartet stacks is only occupied by dehydrated cations and very few water molecules (diameter d = 2.75 Å)69, it is reasonable to assume that a significant number of water-inaccessible voids is present in the G-quartet stacks. Those voids will disappear upon dissociation of the G-quartet structure. Further volume reduction can be obtained from rehydration of the Na+ ions and the nucleobases after release from the channel, as the density of the hydration water is higher compared to that of bulk water57, 70, 71. Elimination of void volume, though of much lesser extent, in the dimer stacks upon pressure-induced formation of monomer stacks explains their pressure sensitivity as well.

Effect of alkali salt on the thermal and pressure stability of 5′-GMP self-assemblies

In a very elegant approach, using NMR titration experiments Wong and Wu have shown that the channel Na+ ions bound to the G-quartet stacks are replaced by K+ and Rb+ ions in a competitive equilibrium, whereas the Na+ ions bound to the peripheral phosphates remain unaffected38. This allows us to explore the thermal and pressure stability of 5′-GMP quartet stacks when the channel Na+ ions are gradually replaced by K+ and Rb+, respectively. Hence, we added increasing amounts of additional MCl to 0.48 M Na25′-GMP. First, we performed temperature-dependent FTIR experiments and studied the thermal stability of the hydrogen-bonded 5′-GMP self-assemblies in the presence of the alkali salts, MCl = NaCl, KCl and RbCl (Suppl. Fig. S5). The IR bands assigned for guanine are not affected by the alkali salts, indicating that additional structures are not formed. The “melting” curves reveal that all three alkali salts are able to increase the thermal stability of the hydrogen-bonded 5′-GMP self-assemblies (Fig. 6a). While the melting temperature, T m, in the presence of additional NaCl is only slightly increased, additional KCl causes a concentration-dependent stabilization of G-quartets against temperature, indicating gradual replacement of the channel Na+ by K+ (Fig. 6b). In contrast, the addition of RbCl induces a moderate stabilization, which seems to be concentration-independent. RbCl could be tested only up to 0.2 M due to precipitation of 5′-GMP at higher concentrations of RbCl. The stabilization effect of these alkali cations follows the affinity order K+ > Rb+ > Na+ found for the channel site38, confirming the hypothesis that the channel cation determines the thermal stability of the G-quartet structure38. To examine the effect of the alkali salts on the pressure stability of the G-quartets, we performed pressure-dependent FTIR and 1H NMR experiments in the presence of 0.2 M additional MCl (Figs 6 and S6). We found KCl to be most effective against pressure-induced dissociation of G-quartets. At 240 MPa and 278 K, the population distribution is 40% G-quartets, 16% dimers, and 44% monomers (Fig. 6c). This is consistent with our complementary FTIR results revealing a stabilization trend of K+ > Rb+ > Na+ (Fig. 6d). This stabilization sequence against pressure can be explained by the concept of optimal packing. The K+ ion has a diameter of 2.66 Å and occupies consequently a larger volume of the channel cavity leading to reduced voids. Furthermore, owing to its low charge density and slightly hydrophobic nature72, K+ is very likely less densely hydrated and thus the volume reduction upon rehydration would be less compared to Na+. Both contributions result in a reduced \(\Delta {V}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{0}}}\) and an improved pressure resistance. In the case of Rb+, the same argumentation should be valid, causing even more increased pressure stability. However, it is very likely that the channel Na+ ions are not completely replaced by Rb+, as the constant for the competition equilibrium has been found to be 1.838. Thus, the observed stabilizing effect is achieved by both cations, Na+ and Rb+, in the channel cavity.

Effect of alkali salts on 5′-GMP self-assembly. (a) Area normalized absorbance intensities of the IR band at ~1537 cm−1 as a function of temperature. Various concentrations of additional alkali salts were added to 0.48 M Na25′-GMP. (b) Melting temperature, T m, as a function of the alkali salt concentration. n = 2–3, error bars indicate mean ± s.d. The pointed lines are drawn to guide the eyes. (c) Population distribution of 0.48 M Na25′-GMP in the presence of 0.2 M additional alkali salt at 278 K and 240 MPa obtained from 1H NMR. Green: G-quartet, orange: dimer, black: monomer. (d) Pressure-dependent absorbance intensities of the IR band at ~1537 cm−1 and at 288 K upon area normalization.

Conclusions

In summary, we have presented to our knowledge the first comprehensive thermodynamic study on the molecular self-assembly of 5′-GMP. Using a combination of scattering and spectroscopic methods, we have studied the stability of supramolecular self-assemblies of 5′-GMP and the stabilization effect of alkali salts over a wide range of temperatures and pressures. We found that under abyssal conditions, where temperatures as low as 5 °C and pressures up to 1 kbar are reached, the G-quartet structure of Na25′-GMP is stable. Beyond those conditions, the G-quartet stacks dissociate laterally into monomer stacks without changing the longitudinal dimension. Hydration, stacking interactions and packing defects play important roles in determining the stability of such supramolecular structures. In the presence of the alkali cations K+ and Rb+, which bind and replace the Na+ cation from the channel cavity of the G-quartet stacks, the temperature and pressure stability of the 5′-GMP quartets is significantly increased. As the G-quartets serve as building blocks of G-quadruplexes, our results provide also insights into how different forces determining the folding of G-quadruplexes are modulated by temperature and pressure. Especially, the pressure effect on the G-quartets can be extrapolated to their oligomeric analogues and help to explain the pressure sensitivity of G-quadruplexes in general62, 71.

Methods

Sample preparation

Disodium guanosine 5′-monophosphate salt hydrate (Na25′-GMP, >99% purity) from yeast was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Stock solutions of GMP (35 wt%) and the alkali salts (1 M) were prepared in doubly distilled water or D2O and filtered (0.2 µm PVDF membrane). 5′-GMP samples were dissolved overnight to ensure homogeneity. The concentration of the stock solution was determined from UV-absorption measurements at a wavelength of 260 nm (20,000-fold dilution, ε 260 = 10674 [M cm−1) and adjusted to the appropriate concentration31. For FTIR measurements, stock solutions of Na25′-GMP in D2O are lyophilized twice before filtration in order to remove H2O from the crystal water. For NMR measurements, Na25′-GMP was dissolved in 1:1 H2O:D2O, the solution was lyophilized, filtered with 0.2 μm spin filters and re-dissolved in 1:1 H2O:D2O. The Na25′-GMP concentration was 0.48 M in all NMR experiments.

Dynamic light scattering

Temperature-dependent DLS experiments were performed using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano S. Scattered light of a 632.8 nm helium-neon laser was analysed at an angle of 173°. The sample was equilibrated for 5 min at each temperature. A total of 3 scans were collected for the sample at each temperature. All samples were analysed in triplicate. For the polydisperse samples, the method of cumulants and a symmetric spherical model were used. The translational diffusion coefficient, D t, values were obtained from the acquired correlograms using the software Zetasizer (Malvern). The D t values were further used to calculate the apparent hydrodynamic diameter, d app,h, considering the Stokes-Einstein equation. The temperature dependence of the dispersant viscosity (H2O) was taken into consideration. We used the following relationship log η(H2O) = 8.128–0.0447 T + 0.0000579T 2, where the unit for η is centipoise (cP, 1 cP = 0.001 kg m−1 s−1).

Temperature- and pressure-dependent FTIR spectroscopy

Temperature-dependent FTIR measurements were performed using a Nicolet 5700 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) equipped with a liquid-nitrogen-cooled MCT detector (HgCdTe) in the wavenumber range of 4000–1100 cm−1 and in the temperature range of 1–70 °C. The sample was placed between two CaF2 windows separated by a mylar spacer (thickness, 50 µm) and assembled in a temperature cell which is connected to an external water bath. The temperature was measured with a digital thermometer placed in the sample cell (accuracy: ±0.5 °C). The sample was equilibrated for 5 min at each temperature before spectra were collected. Pressure-dependent FTIR spectra were collected using a Nicolet 6700 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) equipped with a liquid-nitrogen-cooled MCT detector (HgCdTe) in the wavenumber range of 4000–650 cm−1. Pressure up to 1200 MPa was applied using a P-series diamond anvil cell (DAC) with type IIa diamonds (High Pressure Diamond Optics Inc., Tucson, USA). A 20 µm thick gasket of CrNi steel with a 0.3 mm drilling was placed between the two diamonds holding 2.5 µL of the sample. The temperature of the DAC was controlled by an external water bath and the internal temperature was measured with a digital thermometer. BaSO4 was used as an internal pressure gauge. The stretching vibration of SO4 2− (~983 cm−1) is pressure-dependent73. For each temperature or pressure, 128 scans were collected with a spectral resolution of 2 cm−1 and averaged. Data analysis was carried out using the GRAMS software (Thermo Electron). After buffer subtraction and baseline correction in the range of 1710–1630 cm−1 (band for the C=O stretch vibration) and 1610–1518 cm−1 (band for the C=N ring vibration), those bands were area normalized and smoothed. All measurements were performed at least in duplicate.

Assuming an apparent thermodynamic equilibrium between hydrogen-bonded and monomer assemblies, a Boltzmann function was fitted to the temperature-dependent band intensities at 1673, 1592, 1568 and 1537 cm−1 using

where I 1 and I 2 are the plateau values of the IR band intensities of the monomeric and hydrogen-bonded state, respectively. T m is the melting temperature and \({\rm{\Delta }}{H}_{{\rm{vH}}}^{{\rm{0}}}\) the standard van’t Hoff enthalpy for the dissociation reaction.

High pressure Synchrotron SAXS

Pressure-dependent SAXS measurements were performed at the ESRF beamline ID 02 (Grenoble, France) in a home-built high pressure cell with diamond windows74. The sample volume was 10 µl. The energy used was 16 keV and the sample to detector distance was 2.4 m. The samples were exposed to the beam for 0.25 s for each measurement. No radiation damages were detected within the total exposure time of a complete pressure series. Data were collected in 50 MPa steps. The scattering data were background corrected and analysed using the SAXSutilities software package provided by ESRF75.

High pressure NMR and DOSY NMR

All NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz spectrometer with a standard 5 mm O.D. ceramic tube from Daedelus Innovations. Hydrostatic pressure was applied to the sample using the Xtreme Syringe Pump (Daedelus Innovations). A commercial ceramic zirconia high-pressure NMR cell and an automatic pump system (Daedalus Innovations, Philadelphia, PA) were used to vary the pressure in the 0.1 to 240 MPa range76. Longitudinal relaxation times T 1 were measured for the H8 protons using an inversion recovery experiment, and the data were analysed using the relaxation module of Bruker’s Topspin software. The T 1 values at various temperatures and pressures are given in Supplementary Table S1. The range of T 1 values varied from 1.9 s at 35 °C to 0.8 s at 5 °C for the tetramer, and from 1.4 s at 35 °C to 1 s at 5 °C for the monomer. Conversely, pressure had a very little effect on T 1. Standard 1H NMR experiments were performed with the zgesgp pulse sequence using excitation sculpting for solvent suppression. At each pressure, 16 scans were collected with a recycle delay of 10 s at 15, 25 and 35 °C and 32 scans were collected with a recycle delay of 5 s at 5 °C. The data were processed and analysed on Bruker Topspin software version 3.5 pl 5. For 1H diffusion experiments, the stebpgp1s pulse sequence was used. The pulsed field gradient duration (δ) was 10 ms, the diffusion period (Δ) was 250 ms and the variable gradient strength (G) was 34.05 T/cm. For the gradient, 32 scans were collected for each of 32 linear incremental steps from 2% to 95% of the gradient strength, with a recycle delay of 5 s. The data were analysed using the ‘eddosy’ tool on Bruker Topspin software version 3.5 pl 5. The temperature and pressure dependence of water’s dynamic viscosity was considered77.

The standard-state free energy of dissociation, \({\rm{\Delta }}{G}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{0}}}\), was determined by

where the apparent equilibrium constant, K app, for the disassembly reaction is given by the ratio of the mole fractions of monomer and hydrogen-bonded 5′-GMP assemblies (dimers and G-quartets), f m and f hb.

The standard-state molar volume change of the disassembly process of 5′-GMP, \({\rm{\Delta }}{V}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{0}}}\), was calculated from

that is the slope of the linear plot of \({\rm{\Delta }}{G}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{0}}}(p)\).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Watson, J. D. & Crick, F. H. C. Molecular structure of nucleic acids. Nature 171, 737–738 (1953).

Watson, J. D. & Crick, F. H. Genetical implications of the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid. Nature 171, 964–967 (1953).

Franklin, R. E. & Gosling, R. G. Molecular configuration in sodium thymonucleate. Nature 171, 740–741 (1953).

Kaushik, M. et al. A bouquet of DNA structures: Emerging diversity. Biochem. Biophys. Reports 5, 388–395 (2016).

Rhodes, D. & Lipps, H. J. Survey and summary G-quadruplexes and their regulatory roles in biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 8627–8637 (2015).

Fay, M. M., Lyons, S. M. & Ivanov, P. RNA G-quadruplexes in biology: Principles and molecular mechanisms. J. Mol. Biol. 429, 2127–2147 (2017).

Hänsel-Hertsch, R., Antonio, M., Di & Balasubramanian, S. DNA G-quadruplexes in the human genome: detection, functions and therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 279–284 (2017).

Fleming, A. M., Ding, Y. & Burrows, C. J. Oxidative DNA damage is epigenetic by regulating gene transcription via base excision repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 2604–2609 (2017).

Fedeles, B. I. G-quadruplex–forming promoter sequences enable transcriptional activation in response to oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 2788–2790 (2017).

Neidle, S. Quadruplex nucleic acids as targets for anticancer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0041, doi:10.1038/s41570-017-0041 (2017).

Arora, A. & Maiti, S. Differential biophysical behavior of human telomeric RNA and DNA quadruplex. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 10515–10520 (2009).

Guo, J. U. & Bartel, D. P. RNA G-quadruplexes are globally unfolded in eukaryotic cells and depleted in bacteria. Science 353, aaf5371, doi:10.1126/science.aaf5371 (2016).

Hänsel-Hertsch, R. et al. G-quadruplex structures mark human regulatory chromatin. Nat. Genet. 48, 1267–1272 (2016).

Burge, S., Parkinson, G. N., Hazel, P., Todd, A. K. & Neidle, S. Quadruplex DNA: Sequence, topology and structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 5402–5415 (2006).

Gellert, M., Lipsett, M. N. & Davies, D. R. Helix formation by guanylic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 48, 2013–2018 (1962).

Zimmerman, S. B. X-ray study by fiber diffraction methods of a self-aggregate of guanosine-5′-phosphate with the same helical parameters as poly(rG). J. Mol. Biol. 106, 663–672 (1976).

Kang, C., Zhang, X., Ratliff, R., Moyzis, R. & Rich, A. Crystal structure of four-stranded Oxytricha telomeric DNA. Nature 356, 126–131 (1992).

Williamson, J. R., Raghuraman, M. K. & Cech, T. R. Monovalent cation-induced structure of telomeric DNA: The G-quartet model. Cell 59, 871–880 (1989).

Pinnavaia, T. J. et al. Alkali metal ion specificity in the solution ordering of a nucleotide, 5′-guanosine monophosphate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 100, 3625–3627 (1978).

Laughlan, G. et al. The high-resolution crystal structure of a parallel-stranded guanine tetraplex. Science 265, 520–524 (1994).

Parkinson, G. N., Lee, M. P. H. & Neidle, S. Crystal structure of parallel quadruplexes from human telomeric DNA. Nature 417, 876–80 (2002).

Haider, S., Parkinson, G. N. & Neidle, S. Crystal structure of the potassium form of an Oxytricha nova G-quadruplex. J. Mol. Biol. 320, 189–200 (2002).

Phillips, K., Dauter, Z., Murchie, A. I. H., Lilley, D. M. & Luisi, B. The crystal structure of a parallel-stranded guanine tetraplex at 0.95 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 273, 171–182 (1997).

Delville, A., Detellier, C. & Laszlo, P. Determination of the correlation time for a slowly reorienting spin-3/2 nucleus: Binding of Na+ with the 5′-GMP supramolecular assembly. J. Magn. Reson. 34, 301–315 (1979).

Davis, J. T. G-quartets 40 years later: From 5′-GMP to molecular biology and supramolecular chemistry. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 43, 668–698 (2004).

Williamson, J. R. G-quartet structures in telomeric DNA. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 23, 703–730 (1994).

Sen, D. & Gilbert, W. A sodium-potassium switch in the formation of four-stranded G4-DNA. Nature 344, 410–414 (1990).

Blackburn, E. H. & Gall, J. G. A tandemly repeated sequence at the termini of the extrachromosomal ribosomal RNA genes in Tetrahymena. J. Mol. Biol. 120, 33–53 (1978).

Guschlbauer, W., Chantot, J.-F. & Thiele, D. Four-stranded nucleic acid structures 25 years later: From guanosine gels to telomer DNA. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 8, 491–511 (1990).

Pinnavaia, T. J., Miles, H. T. & Becker, E. D. Self-assembled 5′-guanosine monophospate. nuclear Magnetic resonance evidence for a regular, ordered structure and slow chemical exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 97, 7198–7200 (1975).

Jurga-Nowak, H., Banachowicz, E., Dobek, A. & Patkowski, A. Supramolecular guanosine 5′-monophosphate structures in solution. Light scattering study. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 2744–2750 (2004).

Wong, A., Ida, R., Spindler, L. & Wu, G. Disodium guanosine 5′-monophosphate self-associates into nanoscale cylinders at pH 8: A combined diffusion NMR spectroscopy and dynamic light scattering study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 6990–6998 (2005).

Bang, I. Untersuchungen über die Guanylsäure. Biochem. Z. 26, 293–311 (1910).

Wu, G. & Kwan, I. C. M. Helical structure of disodium 5′-guanosine monophosphate self-assembly in neutral solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 3180–3182 (2009).

Eimer, W. & Dorfmüller, T. Interaction of the complementary mononucleotides in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. 96, 6801–6804 (1992).

Borzo, M., Detellier, C., Laszlo, P. & Paris, A. Proton, sodium-23, and phosphorus-31 NMR studies of the self-assembly of the 5′-guanosine monophosphate dianion in neutral aqueous solution in the presence of sodium cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102, 1124–1134 (1980).

Detellier, C. & Laszlo, P. Role of alkali metal and ammonium cations in the self-assembly of the 5′-guanosine monophosphate dianion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102, 1135–1141 (1980).

Wong, A. & Wu, G. Selective binding of monovalent cations to the stacking G-quartet structure formed by guanosine 5′-monophosphate: A solid-state NMR study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 13895–13905 (2003).

Wong, A., Fettinger, J. C., Forman, S. L., Davis, J. T. & Wu, G. The sodium ions inside a lipophilic G-quadruplex channel as probed by solid-state 23Na NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 742–743 (2002).

Wu, G., Wong, A., Gan, Z. & Davis, J. T. Direct detection of potassium cations bound to G-quadruplex structures by solid-state 39K NMR at 19.6 T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 7182–7183 (2003).

Gu, J., Leszczynski, J. & Bansal, M. A new insight into the structure and stability of Hoogsteen hydrogen-bonded G-tetrad: an ab initio SCF study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 311, 209–214 (1999).

Meyer, M., Steinke, T., Brandl, M. & Sühnel, J. Density functional study of guanine and uracil quartets and of guanine quartet/metal ion complexes. J. Comput. Chem. 22, 109–124 (2000).

Sundquist, W. I. & Klug, A. Telomeric DNA dimerizes by formation of guanine tetrads between hairpin loops. Nature 342, 825–829 (1989).

Ross, W. S. & Hardin, C. C. Ion-induced stabilization of the G-DNA quadruplex - Free-energy perturbation studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 6070–6080 (1994).

Hud, N. V., Smith, F. W., Anet, F. A. L. & Feigon, J. The selectivity for K+ versus Na+ in DNA quadruplexes is dominated by relative free energies of hydration: A thermodynamic analysis by 1H NMR. Biochemistry 35, 15383–15390 (1996).

Gu, J. & Leszczynski, J. Origin of Na+/K+ selectivity of the guanine tetraplexes in water: The theoretical rationale. J. Phys. Chem. A 106, 529–532 (2002).

Orgel, L. E. Evolution of the genetic apparatus. J. Mol. Biol. 38, 381–393 (1968).

Crick, F. H. C. The origin of the genetic code. J. Mol. Biol. 38, 367–379 (1968).

Cassidy, L. M., Burcar, B. T., Stevens, W., Moriarty, E. M. & McGown, L. B. Guanine-centric self-assembly of nucleotides in water: An important consideration in prebiotic chemistry. Astrobiology 14, 876–886 (2014).

Callahan, M. et al. Carbonaceous meteorites contain a wide range of extraterrestrial nucleobases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 13995–13998 (2011).

Douglas, R. H., Partridge, J. C. & Marshall, N. J. The eyes of deep-sea fish I: Lens pigmentation, tapeta and visual pigments. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 17, 597–636 (1998).

Miles, H. T. & Frazier, J. Infrared spectra in 2H2O solution of guanylic acid helices and of poly-G. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 79, 216–220 (1964).

Fisk, C. L., Becker, E. D., Todd, H. & Pinnavaia, T. J. Self-structured guanosine 5′-monophosphate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104, 3307–3314 (1982).

Saenger, W. Principles of nucleic acid structure. Springer: New York (1984).

Meersman, F. et al. High-pressure biochemistry and biophysics. Rev. Miner. Geochem. 75, 607–648 (2013).

Luong, T. Q., Kapoor, S. & Winter, R. Pressure - A gateway to fundamental insights into protein solvation, dynamics and function. ChemPhysChem 16, 3555–3571 (2015).

Chalikian, T. V. Structural thermodynamics of hydration. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 12566–12578 (2001).

Girard, E. et al. Adaptation of the base-paired double-helix molecular architecture to extreme pressure. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 4800–4808 (2007).

Wilton, D. J., Ghosh, M., Chary, K. V. A., Akasaka, K. & Williamson, M. P. Structural change in a B-DNA helix with hydrostatic pressure. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 4032–4037 (2008).

Dubins, D. N., Lee, A., Macgregor, R. B. & Chalikian, T. V. On the stability of double stranded nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 9254–9259 (2001).

Amiri, A. R. & Macgregor, R. B. The effect of hydrostatic pressure on the thermal stability of DNA hairpins. Biophys. Chem. 156, 88–95 (2011).

Takahashi, S. & Sugimoto, N. Effect of pressure on the stability of G-quadruplex DNA: Thermodynamics under crowding conditions. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 52, 13774–13778 (2013).

Smeller, L., Meersman, F., Fidy, J. & Heremans, K. High-pressure FTIR study of the stability of horseradish peroxidase. Effect of heme substitution, ligand binding, Ca++ removal, and reduction of the disulfide bonds. Biochemistry 42, 553–561 (2003).

Lin, M. C., Eid, P., Wong, P. T. T. & MacGregor, R. B. High pressure fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of poly(dA)poly(dT), poly(dA) and poly(dT). Biophys. Chem. 76, 87–94 (1999).

Perahia, D., Jhon, M. S. & Pullman, B. Theoretical study of the hydration of B-DNA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 474, 349–362 (1977).

Visser, A. J. W. G., Li, T. M., Drickamer, H. G. & Weber, G. Volume changes in the formation of internal complexes of flavinyltryptophan peptides. Biochemistry 16, 4883–4886 (1977).

Ausili, P. et al. Pressure effects on columnar lyotropics: Anisotropic compressibilities in guanosine monophosphate four-stranded helices. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 1783–1789 (2004).

Kitamura, Y. & Itoh, T. Reaction volume of protonic ionization for buffering agents. Prediction of pressure dependence of pH and pOH. J. Solution Chem. 16, 715–725 (1987).

Federiconi, F., Ausili, P., Fragneto, G., Ferrero, C. & Mariani, P. Locating counterions in guanosine quadruplexes: a contrast-variation neutron diffraction experiment in condensed hexagonal phase. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 11037–11045 (2005).

Son, I., Shek, Y. L., Dubins, D. N. & Chalikian, T. V. Hydration changes accompanying helix-to-coil DNA transitions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 4040–4047 (2014).

Fan, H. Y. et al. Volumetric characterization of sodium-induced G-quadruplex formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 4518–4526 (2011).

Collins, K. D. Charge density-dependent strength of hydration and biological structure. Biophys. J. 72, 65–76 (1997).

Wong, P. T. T. & Moffatt, D. J. A new internal pressure calibrant for high-pressure infrared spectroscopy of aqueous systems. Appl. Spectrosc. 43, 1279–1281 (1989).

Krywka, C. et al. The small-angle and wide-angle X-ray scattering set-up at beamline BL9 of DELTA. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 14, 244–251 (2007).

Sztucki, M. & Narayanan, T. Development of an ultra-small-angle X-ray scattering instrument for probing the microstructure and the dynamics of soft matter. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 459–462 (2006).

Peterson, R. W. & Wand, A. J. Self-contained high-pressure cell, apparatus, and procedure for the preparation of encapsulated proteins dissolved in low viscosity fluids for nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 76, 94101 (2005).

Harris, K. R., Woolf, L. A., Harris, K. R. & Woolf, L. A. Temperature and volume dependence of the viscosity of water and heavy water at low temperatures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 49, 1064–1069 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from DFG Research Unit FOR 1979, the Deep Carbon Observatory (Alfred P. Sloan Foundation), and the Cluster of Excellence RESOLV (EXC 1069). We are grateful to Dr. Johannes Möller at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France) for providing assistance in using beamline ID02. M.G. is supported by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G. and R.W. designed the research, M.G., B.H., M.B., R.S. and L.A. performed research, M.G. and B.H. analysed data, S.A.M. assisted with NMR experiments, C.A.R. contributed analytic tools, M.G. and R.W. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, M., Harish, B., Berghaus, M. et al. Temperature and pressure limits of guanosine monophosphate self-assemblies. Sci Rep 7, 9864 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10689-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10689-0

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.