Abstract

Functional constipation (FC) is a gastrointestinal disorder with a high prevalence among the general population. The precise causes of FC are still unknown and are most likely multifactorial. Growing evidence indicates that alterations of gut microbiota composition contribute to constipation symptoms. Nevertheless, many discrepancies exist in literature and no clear link between FC and gut microbiota composition has as yet been identified. In this study, we performed 16 S rRNA-based microbial profiling analysis of 147 stool samples from 68 FC individuals and compared their microbial profiles with those of 79 healthy subjects (HS). Notably, the gut microbiota of FC individuals was shown to be depleted of members belonging to Bacteroides, Roseburia and Coprococcus 3. Furthermore, the metabolic capabilities of the gut microbiomes of five FC and five HS individuals were evaluated through shotgun metagenomics using a MiSeq platform, indicating that HS are enriched in pathways involved in carbohydrate, fatty acid and lipid metabolism as compared to FC. In contrast, the microbiomes corresponding to FC were shown to exhibit high abundance of genes involved in hydrogen production, methanogenesis and glycerol degradation. The identified differences in bacterial composition and metabolic capabilities may play an important role in development of FC symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The human gastrointestinal tract is colonized by complex communities of microorganisms, i.e. the gut microbiota, that are involved in several physiological functions of the host. These encompass metabolic, nutritional, physiological and immunological processes that are vital to maintain the host’s health status1, 2. In this context, alterations in the gut microbiota composition have been linked to certain common human intestinal diseases, such as pseudomembranous colitis (CDI)3,4,5,6,7,8, ulcerative colitis (UC)9,10,11 and Crohn’s disease (CD)9, 12, 13. However, changes in the gut microbiota composition are also considered to play a crucial role in the establishment of gut related disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)14,15,16. Functional constipation (FC) is a common gastrointestinal disorder with a prevalence between 5% and 20% of the general population17, 18, provoking a significant impact on quality of life19. In fact, it can result in discomforts such as abdominal distension, abdominal pain, headache, dizziness and loss of appetite20. Despite its high prevalence, only a small number of studies have investigated its possible correlation with particular gut microbiota alterations. Additionally, most of these studies relied on culture-based methods that are unable to assess the unculturable portion of the gut microbiota21, 22. Moreover, the functional implications of these alterations and their impact on host physiology have never been assessed. Recently, two metagenomic studies compared the microbial population of stools collected from constipated and healthy individuals, highlighting an altered fecal microbiome associated with constipation23, 24. However, these studies were limited by the small sample size and heterogeneity of participants (including women or obese children). Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that the observed differences in microbiota composition among healthy and constipated patients suffer from a number of discrepancies20.

Here, in order to identify a statistically significant and comprehensive correlation between microbiota and constipation, we performed 16 S rRNA-based profiling analysis of 147 stool samples collected from 68 functional constipated (FC) and 79 healthy subjects (HS). Furthermore, in order to better understand the role of the microbiome and its metabolic impact on the host, the gut microbiome of a random subsampling of 10 samples, five FC and five HS samples, was reconstructed and analyzed in detail by shotgun metagenomic analyses.

Results and Discussion

Patient enrollment and collection of fecal samples

In this study, we collected and analyzed 147 human stool samples from Italian subjects. More specifically, we obtained 68 samples from individuals affected by functional constipation (FC), while 44 samples were collected from healthy subjects (HS). The HS dataset was supplemented with data from 35 samples that we published previously8, 25. Notably, these samples had been collected and processed using the same protocols as followed for the 112 samples sequenced in the current study (see below for details). Moreover, analysis of variance of beta-diversity was performed between each pool of samples processed in different sequencing runs, and the obtained data showed absence of any batch effects (Fig. S1a). In order to identify microbial biomarkers of functional constipation across all age ranges, we selected individuals with an age ranging from 4 to 94 (average age: 42 ± 22 years) (Table S1). Remarkably, beta-diversity and PERMANOVA analyses displayed absence of age-related clustering of the samples (Fig. S1b). Moreover, the enrolled individuals were not taking prebiotics and/or probiotics, not undergoing antibiotic treatment or any other medical therapy (including those specific for functional constipation such laxatives for one week prior sampling) and not suffering from acute or severe intestinal diseases such as ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn’s disease, acute inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), intestinal cancer and enteritis. Notably, functionally constipated individuals also reporting symptoms typical of IBS-C, such as abdominal pain, were excluded from this study. The selected individuals affected by functional constipation fulfill the ROME-III criteria and manifested infrequent bowel movements that are defined as three or less defecations per week26. Notably, statistical assessment of diet homogeneity of FC and HS groups revealed absence of statistically significant differences (Table S2). In order to avoid discrepancies in the in silico data, all newly sequenced as well as previously published datasets included in this study were subjected to bioinformatic analysis using the same pipeline based on a custom script for the Qiime software suite and the same 16 S rRNA database (see Methods for details).

Intra- and Inter-individual variability among healthy and functionally constipated subjects

Stool samples from the 147 individuals enrolled in this study were obtained in order to assess the microbiota composition based on 16 S rRNA-based sequencing analysis, as described previously27. MiSeq-mediated sequencing of the samples produced a total of 18,673,728 reads with an average of 127,032 ± 69,090 reads per sample (Table S2). Quality and chimera filtering produced a total of 10,164,847 filtered reads with an average of 69,149 filtered reads per sample, and ranging from 185,347 to 10,440 reads (Table S2).

Evaluation of rarefaction curves obtained through the Shannon and Chao1 biodiversity indeces calculated for 10 sub-samplings of sequenced read pools showed that both curves tend to reach a plateau. Therefore, in all cases the retrieved sequencing data is considered adequate to cover the vast majority of biodiversity contained within the samples (Fig. 1). Interestingly, average rarefaction curves revealed a difference between FC and HS samples in that, on average, the former samples were shown to exhibit a higher level of gut microbiota complexity compared to the latter samples. Statistical analysis, calculated for the highest sub-sampling point reached by all samples, i.e. 30,000 reads, showed that the two curves significantly differ based on a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (p-value < 0.05). The observed dissimilarity of the alpha-diversity between FC and HS is in accordance with a previous study24, being indicative of differences in bacterial composition and corresponding metabolic potential (see below). In order to evaluate the inter-individual differences between FC and HS samples in more detail, we assessed the beta-diversity28 by means of unweighted UniFrac29 and represented the results through a 3-Dimensional Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA). The PCoA plot shows that the majority of the samples are grouped as two different clusters that correspond to FC or HS individuals, thus highlighting an intriguing difference in microbiota composition between individuals that suffer from functional constipation and healthy individuals (Fig. 1). Notably, the obtained results were statistically supported by PERMANOVA analyses (p-value of <0.001).

Evaluation of the alpha- and beta-diversity in the 147 analyzed samples. Panel a reports the average rarefaction curves based on the Chao1 and Shannon index at increasing sequencing depth of FC and HS samples. Panel b shows the predicted PCoA through two three-dimensional images and two-dimensional sections. FC and HS datasets and corresponding clusters are colored in blue and red, respectively.

Taxonomic profiling of the gut microbiota of functionally constipated and healthy individuals

Inspection of the predicted taxonomic profiles showed that both FC and HS samples possess a preponderant presence of the phyla Bacteroidetes (50.44% ± 18.29% and 58.37% ± 16.59%, respectively; p-value < 0.05) and Firmicutes (44.19% ± 17.02% and 36.65% ± 15.65%, respectively; p-value < 0.05), although with a significantly different average relative abundance (Fig. S2). When analyzed at genus level, the FC group displayed high levels of Bacteroides (34.25% ± 18.56%), Faecalibacterium (6.85% ± 6.19%), Alistipes (6.48% ± 9.69%), Lachnospira (4.44% ± 6.13%) and Unclassified member of Lachnospiraceae family (3.92% ± 2.40%). Similarly, the most represented taxa detected in HS samples were Bacteroides (45.23% ± 17.90%), Alistipes (5.34% ± 5.60%) and Unclassified member of Lachnospiraceae family (4.66% ± 4.38%).

Comparative analysis of the 331 bacterial taxa predicted by genus-level analysis revealed that 23 genera appeared to be present only in HS samples, while 17 were uniquely present in FC subjects (Table. S3). Analysis of the proportion of these unique genera found in each group, i.e. the prevalence, showed that these taxa are present in <20% of FC or HS profiles, thus indicating the absence of specific microbial biomarkers whose presence or absence is associated with constipation while pointing at a probable role played by the overall gut microbiota at functional level.

Difference in gut microbiota composition

In order to evaluate possible differences in bacterial composition, ANOVA statistical analysis was employed to compare the average relative abundance in FC and HS groups of genera with an absolute percentage difference >0.1% (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the comparison between HS and FC datasets showed that profiles obtained from HS individuals are characterized by a statistically significant over-representation of Bacteroides (% absolute 1.28%, p-value < 0.01), Roseburia (% absolute 1.28%, p-value < 0.01) and Coprococcus 3 (% absolute 0.14%, p-value < 0.01) and a statistically significant under-representation of genera belonging to the Ruminococcaceae family such as Faecalibacterium (% absolute −3.54%, p-value < 0.01) (Fig. 2). The depletion of the Bacteroides genus in FC samples may be correlated with alterations of the intestinal motility and secretory functions due to changes in the amount of available physiologically active substances in the metabolic environment of the gut20, 30. In fact, the higher abundance of butyrate-producing taxa, such as Coprococcus and Roseburia, observed in HS samples may explain a faster colonic transit due to the motility-stimulating effect exerted by butyrate in the gut1. In this context, previous studies have reported that butyrate-producing taxa may stimulate colonic motility by induction of serotonin release or by facilitating cholinergic pathways by means of butyrate production31, 32. In contrast, despite being a butyrate-producer, Faecalibacterium is significantly more abundant in FC samples. Interestingly, this genus has been reported to contribute to the pathogenesis of constipation via several mechanisms, such as inhibition of mucin secretion and reduction of stool volume24.

Exploration of the diversity in HS and FC groups. The bar plot reports only genera with an absolute percentage difference between HS and FC averages >0.1% and a p-value < 0.05, evaluated by means of ANOVA statistical analysis. The table indicates the bacterial genera, the relative abundance and the prevalence of each group, the relative percentage difference and the p-value.

Metagenomic characterization of FC and HS microbiomes

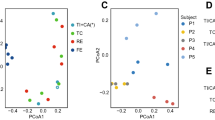

A total of 10 individuals were selected among the two clusters obtained from the PCoA analysis (Fig. 1b) as representatives of the FC and HS groups, and total bacterial DNA extracted from corresponding fecal samples was subjected to Illumina shotgun sequencing. These samples were selected on the basis of their microbial profiles that were shown to be closer to the average for each group. Collected read pools ranged from 8,656,289 to 2,885,092 after quality filtering, with an average number of reads per sample of 6,130,802 (Table S4). These data were then utilized for the reconstruction of metabolic pathway profiles in the analyzed microbiomes by means of a custom script based on the MetaCyc database33. A comparison between the averages of functionally constipated and the averages of healthy samples showed a significant difference in 629 pathways (p-value < 0.05). Of the latter, 327 and 302 pathways were more abundant in FC and HS samples, respectively (Table S5). Interestingly, the HS samples exhibited a higher abundance of genes (p-value < 0.05) involved in carbohydrate (increase of 21.15%) and fatty acid metabolism (increase of 25.93%) as compared to FC individuals (Fig. 3b). These pathways are implicated in production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and may play a role in stimulating ileal propulsive contractions through an enteric cholinergic reflex, thereby counteracting functional constipation20, 34,35,36. Moreover, FC samples were shown to contain a higher abundance of genes involved in methanogenic pathways (increase of 24.96%, p-value < 0.01) and a predicted higher capability to produce hydrogen (increase of 113.69%, p-value 0.05) as compared to HS (Table S5, Fig. 3b). Thus, our data are consistent with previous observations and suggest that the (abundant) presence of methanogenic and H2-consuming populations influence colonic motility and visceral sensitivity, and generate chronic constipation along with several correlated symptoms, such as flatulence and abdominal distension37, 38. Interestingly, datasets obtained from functionally constipated individuals showed lower abundance of genes involved in methylglyoxal degradation as compared to healthy samples (decrease of −25.18%, p-value < 0.05) (Fig. 3b). Methylglyoxal is produced by intestinal bacteria and it is reported be a potential toxic metabolite that can be involved in many gut diseases, including functional constipation39. Furthermore, comparison between HS and FC samples highlights a significant difference in pathways implicated in glycerol degradation (decrease of −58.93% in HS, p-value < 0.05) (Fig. 3b). Glycerol is known to cause an osmotic effect in the rectum and for this reason is used to treat constipation40. Therefore, the increased ability to degrade glycerol by FC samples may induce and promote the symptoms of constipation. Nevertheless, despite the fact that the use of laxatives in the week before sampling was considered as a exclusion criterion, this observation may be linked to previous and prolonged use of PEG or glycerol suppositories.

In addition, we evaluated co-variance between the bacterial genera and metabolic pathways displaying difference in abundance (ANOVA p-value < 0.05) in FC as compared to HS subjects. Force-driven network representation of these data revealed that Bacteroides (124 co-variances, p-value < 0.05), genera belonging Ruminococcaceae family (a total of 270 co-variances, p-value < 0.05) and the methanogenic genus Gelria (108 interactions, p-value < 0.05) exert a key role in modulating the metabolic functionalities of the gut microbiome that are altered during FC (Fig. 4a).

Co-variance network of bacterial genera and metabolic pathways with statistically significant difference in abundance between FC and HS subjects. Panel a shows a force-driven network based on the predicted co-variances with p-values < 0.05 between the genera and metabolic pathways identified as statistically altered in FC as compared to HS. Panel b reports a force-driven network based on the predicted co-variances with p-values < 0.05 between genera and metabolic pathways putatively involved in FC development. Co-variances with p-values < 0.05 are used to define the attractive or repulsive force of the edges. The node size is proportional to the number of co-variances. Node color indicates phylum or pathway category as reported in the image. The taxonomy, i.e. bacterial genera, of the nodes is indicated with number, as listed in the table.

Moreover, a force-driven network representation based on the above-discussed pathways that may be related to FC development revealed that the Firmicutes phylum positively correlates with pathways involved in hydrogen production and methanogenesis, while Bacteroides correlates positively with the methylglyoxal degradation pathways (Fig. 4b). These results reflect the putative beneficial role played by Bacteroides to counter FC as also suggested by the higher abundance of this genus in HS with respect to FC samples (see above). Notably, an in depth analysis of 16 S rRNA OTUs of HS samples revealed that 17.33% of the reads belonging to the Bacteroides genus correspond to unknown species, followed by Bacteroides vulgatus (13.83%), Bacteroides uniformis (4.21%) and Bacteroides fragilis (1.74%), thus indicating that further genomic analyses are still needed to shed light on the biological role of this genus in protecting against or in preventing FC.

Conclusions

Functional constipation is a widespread gastrointestinal disorder responsible for difficult or infrequent bowel movements defined as three or less defecations per week26. Despite the high worldwide prevalence of FC, a clear anatomical or physiological cause for this disorder has yet to be identified, thus pointing at a possible role exerted by the gut microbiota. Here, we confirm preliminary findings regarding gut microbiota compositional shifts in individuals affected by FC as compared to healthy controls, which are concurrent with a statistically significant increase of the gut microbiota biodiversity. Moreover, statistical analysis revealed alterations in relative abundance of specific taxa, such as Bacteroides and Feacalibacterium. Disregarding the fact that the cause of such taxonomic changes can’t be linked to a specific physiological cause and may simply reflect altered transit time or diet, these taxa will be pivotal for diagnostic and prophylactic purposes as statistically-supported microbial biomarkers of constipation. Intriguingly, identification of taxa typically associated to a healthy gut status, e.g. the anti-inflammatory genus Feacalibacterium, as a biomarker of functional constipation, highlights that increased relative abundance of certain taxa in the presence of a gut disorder may not reflect a taxa-specific role in pathogenesis but may be linked to a global alteration of gut microbiota’s homeostasis. Notably, the taxonomic profiles retrieved from faecal samples include both the autochthonous as well as the allochthonous microbiota, and may thus not be fully representative of the resident gut microbial population. In contrast, the use of biopsies from mucosal samples would be ideal to provide information on the indigenous microbiota41. Nevertheless, collection of fecal samples is less invasive and does not require specific clinical procedures. Thus, for a rapid screening aimed at the identification of biomarkers associated with specific disorders, e.g. functional constipation, the use of stool samples does not suffer from the aforementioned problems associated with collection of biopsies.

While exploration of the functional role of the gut microbiota in fecal transit time42 has been attempted in the past through analysis of urine metabolites, the whole gut microbiome metabolic potential and its impact on host physiology and development of functional constipation has yet to be elucidated. To overcome this gap, we profiled metabolic pathways of microbiomes corresponding to functionally constipated and healthy individuals. The here reconstructed gut microbiome of individuals affected by functional constipation revealed for the first time that the FC microbiome is characterized by a high abundance of genes involved in hydrogen production, methanogenesis and glycerol degradation. In contrast, the microbiomes of HS samples showed an increase of pathways implicated in carbohydrate and fatty acid metabolism, and in methylglyoxal degradation. Alteration of these metabolic pathways appears to impact on functional constipation and related symptoms, thus highlighting the key functional role exerted by the gut microbiome in maintaining the health status of the host. Nevertheless, due to the limited number of samples that were analysed by shotgun sequencing, additional experiments are needed to validate these observations.

Altogether, taxonomic and functional data reported in this study represent a solid base for future development of both prophylactic screenings and therapies for functional constipation based on alterations of gut microbiota composition through personalized diet or pre- and pro-biotic treatments.

Methods

Datasets included in this study

We enrolled 68 volunteers suffering from functional constipation (FC) and 44 healthy subjects (HS) in an outpatient clinic setting. The individuals affected by functional constipation presented infrequent bowel movements and fulfilled the ROME-III criteria. A stool sample, consisting of 6–10 g fresh fecal material, was obtained from each subject and immediately frozen at −80 °C until it was processed for DNA extraction. DNA was extracted from each stool sample using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini kit (Qiagen Ltd, Strasse, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen Ltd). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Parma. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All investigations were carried out following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

16 S rRNA gene amplification

Partial 16 S rRNA gene sequences were amplified from extracted DNA using primer pair Probio_Uni and/Probio_Rev, which targets the V3 region of the 16 S rRNA gene sequence27. Illumina adapter overhang nucleotide sequences were then added to the partial 16 S rRNA gene-specific amplicons, which in turn were further processed by employing the 16 S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation Protocol (Part no. 15044223 Rev. B—Illumina; see also below). Amplifications were carried out using a Verity Thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). The integrity of the PCR amplicons was analyzed by electrophoresis on a 2200 TapeStation Instrument (Agilent Technologies, USA).

MiSeq sequencing of 16 S rRNA gene-based amplicons

PCR products obtained following amplification of part of the 16 S rRNA gene sequences were purified by a magnetic purification step involving Agencourt AMPure XP DNA purification beads (Beckman Coulter Genomics GmbH, Bernried, Germany) in order to remove primer dimers. The DNA concentration of the amplified sequence library was estimated through fluorimetric Qubit quantification system (Life Technologies). Amplicons were diluted to 4 nM and 5 μl of each diluted DNA amplicon sample was mixed to prepare the pooled final library. Sequencing was performed using an Illumina MiSeq sequencer with MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 chemicals.

Analysis of 16 S rRNA microbial profiling datasets

The fastq files were processed using QIIME28 as previously described27. Paired-end reads were merged, and quality control implementation allowed the retention of sequences with a length between 140 and 400 bp, mean sequence quality score >25 and with truncation of a sequence at the first base if a low quality within a rolling 10-bp window was found. Sequences with mismatched forward and/or reverse primers were omitted. 16 S rRNA operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were defined at ≥ 97% sequence homology using uclust43. All reads were classified to the lowest possible taxonomic rank using QIIME28 and a reference dataset from the SILVA database v. 12344. The microbial richness of the samples (alpha-diversity) was evaluated with the Chao1 and Shannon index through the alpha_rarefaction.py script included in the Qiime software suite using default parameters. Similarities between samples (beta-diversity) were calculated by unweighted uniFrac45. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) representations of beta-diversity were performed using QIIME28.

Shotgun metagenomics

DNA library preparation was performed using the Nextera XT DNA sample preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, 1 ng input DNA from each sample was used for library preparation. The isolated DNA underwent fragmentation, adapter ligation and amplification. The ready-to-go libraries were pooled equimolarly, denaturated and diluted to a sequencing concentration of 1.8 pM. Sequencing was performed on NextSeq. 550 instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using the 2 × 150 bp High Output sequencing kit, and spike-in of 1% PhiX control library.

Analysis of metagenomic datasets

The generated paired fastq files were filtered for reads with a quality score of <25, for sequences of human DNA, as well as for reads <80 bp. Bases were also removed from the end of the reads unless the average quality score in a window of 5 bp was >25. Reconstruction of bacterial metabolic pathways was performed using custom scripts based on htseq-count46 and the MetaCyc database33, respectively.

Statistical analyses

QIIME and SPSS software (www.ibm.com/software/it/analytics/spss/) were used to complete statistical analysis. All data were presented as means ± SEM. PERMANOVA were performed using 999 permutations to estimate p-values for differences among populations. Furthermore, differential abundance of bacteria taxa and metabolic pathways were tested by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Data Deposition

The 16 S rRNA profiling data sequenced in this study were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the SRP106879 accession number. Shotgun metagenomics data are accessible through SRA study accession number SRP106935.

References

Chassard, C. et al. Functional dysbiosis within the gut microbiota of patients with constipated-irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 35, 828–838, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05007.x (2012).

Round, J. L. & Mazmanian, S. K. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 9, 313–323, doi:10.1038/nri2515 (2009).

Zhang, L. et al. Insight into alteration of gut microbiota in Clostridium difficile infection and asymptomatic C. difficile colonization. Anaerobe 34, 1–7, doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.03.008 (2015).

Rojo, D. et al. Clostridium difficile heterogeneously impacts intestinal community architecture but drives stable metabolome responses. The ISME journal 9, 2206–2220, doi:10.1038/ismej.2015.32 (2015).

Khanna, S. et al. Gut microbiome predictors of treatment response and recurrence in primary Clostridium difficile infection. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 44, 715–727, doi:10.1111/apt.13750 (2016).

Abujamel, T. et al. Defining the vulnerable period for re-establishment of Clostridium difficile colonization after treatment of C. difficile infection with oral vancomycin or metronidazole. PloS one 8, e76269, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076269 (2013).

Gu, S. et al. Identification of key taxa that favor intestinal colonization of Clostridium difficile in an adult Chinese population. Microbes and infection 18, 30–38, doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2015.09.008 (2016).

Milani, C. et al. Gut microbiota composition and Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalized elderly individuals: a metagenomic study. Scientific reports 6, 25945, doi:10.1038/srep25945 (2016).

Tong, M. et al. A modular organization of the human intestinal mucosal microbiota and its association with inflammatory bowel disease. PloS one 8, e80702, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080702 (2013).

Shah, R. et al. Composition and function of the pediatric colonic mucosal microbiome in untreated patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut microbes 7, 384–396, doi:10.1080/19490976.2016.1190073 (2016).

Duranti, S. et al. Elucidating the gut microbiome of ulcerative colitis: bifidobacteria as novel microbial biomarkers. FEMS microbiology ecology 92, doi:10.1093/femsec/fiw191 (2016).

Weir, T. L. et al. Stool microbiome and metabolome differences between colorectal cancer patients and healthy adults. PloS one 8, e70803, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070803 (2013).

Mondot, S. et al. Structural robustness of the gut mucosal microbiota is associated with Crohn’s disease remission after surgery. Gut 65, 954–962, doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309184 (2016).

Pozuelo, M. et al. Reduction of butyrate- and methane-producing microorganisms in patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Scientific reports 5, 12693, doi:10.1038/srep12693 (2015).

Saulnier, D. M. et al. Gastrointestinal microbiome signatures of pediatric patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 141, 1782–1791, doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.072 (2011).

Ringel-Kulka, T. et al. Molecular characterization of the intestinal microbiota in patients with and without abdominal bloating. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology 310, G417–426, doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00044.2015 (2016).

Lovell, R. M. & Ford, A. C. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 10, 712–721 e714, doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029 (2012).

Suares, N. C. & Ford, A. C. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic idiopathic constipation in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of gastroenterology 106, 1582-1591; quiz 1581, 1592, doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.164 (2011).

Belsey, J., Greenfield, S. & Candy, D. & Geraint, M. Systematic review: impact of constipation on quality of life in adults and children. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 31, 938–949, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04273.x (2010).

Zhao, Y. & Yu, Y. B. Intestinal microbiota and chronic constipation. SpringerPlus 5, 1130, doi:10.1186/s40064-016-2821-1 (2016).

Khalif, I. L., Quigley, E. M., Konovitch, E. A. & Maximova, I. D. Alterations in the colonic flora and intestinal permeability and evidence of immune activation in chronic constipation. Digestive and liver disease: official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver 37, 838–849, doi:10.1016/j.dld.2005.06.008 (2005).

Zoppi, G. et al. The intestinal ecosystem in chronic functional constipation. Acta paediatrica 87, 836–841 (1998).

Parthasarathy, G. et al. Relationship Between Microbiota of the Colonic Mucosa vs Feces and Symptoms, Colonic Transit, and Methane Production in Female Patients With Chronic Constipation. Gastroenterology 150, 367–379 e361, doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.10.005 (2016).

Zhu, L. et al. Structural changes in the gut microbiome of constipated patients. Physiological genomics 46, 679–686, doi:10.1152/physiolgenomics.00082.2014 (2014).

Ferrario, C. et al. Modulation of fecal Clostridiales bacteria and butyrate by probiotic intervention with Lactobacillus paracasei DG varies among healthy adults. The Journal of nutrition 144, 1787–1796, doi:10.3945/jn.114.197723 (2014).

Jamshed, N., Lee, Z. E. & Olden, K. W. Diagnostic approach to chronic constipation in adults. American family physician 84, 299–306 (2011).

Milani, C. et al. Assessing the fecal microbiota: an optimized ion torrent 16S rRNA gene-based analysis protocol. PloS one 8, e68739, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068739 (2013).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature methods 7, 335–336, doi:10.1038/nmeth.f.303 (2010).

Lozupone, C., Lladser, M. E., Knights, D., Stombaugh, J. & Knight, R. UniFrac: an effective distance metric for microbial community comparison. The ISME journal 5, 169–172, doi:10.1038/ismej.2010.133 (2011).

Kim, S. E. et al. Change of Fecal Flora and Effectiveness of the Short-term VSL#3 Probiotic Treatment in Patients With Functional Constipation. Journal of neurogastroenterology and motility 21, 111–120, doi:10.5056/jnm14048 (2015).

Reigstad, C. S. et al. Gut microbes promote colonic serotonin production through an effect of short-chain fatty acids on enterochromaffin cells. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 29, 1395–1403, doi:10.1096/fj.14-259598 (2015).

Soret, R. et al. Short-chain fatty acids regulate the enteric neurons and control gastrointestinal motility in rats. Gastroenterology 138, 1772–1782, doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.053 (2010).

Caspi, R. et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of Pathway/Genome Databases. Nucleic acids research 42, D459–471, doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1103 (2014).

Coffin, B. et al. Local regulation of ileal tone in healthy humans. The American journal of physiology 272, G147–153 (1997).

Kamath, P. S., Phillips, S. F. & Zinsmeister, A. R. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate ileal motility in humans. Gastroenterology 95, 1496–1502 (1988).

Ge, X. et al. Potential role of fecal microbiota from patients with slow transit constipation in the regulation of gastrointestinal motility. Scientific reports 7, 441, doi:10.1038/s41598-017-00612-y (2017).

Attaluri, A., Jackson, M., Valestin, J. & Rao, S. S. Methanogenic flora is associated with altered colonic transit but not stool characteristics in constipation without IBS. The American journal of gastroenterology 105, 1407–1411, doi:10.1038/ajg.2009.655 (2010).

Soares, A. C., Lederman, H. M., Fagundes-Neto, U. & de Morais, M. B. Breath hydrogen test after a bean meal demonstrates delayed oro-cecal transit time in children with chronic constipation. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 41, 221–224 (2005).

Zhang, S. et al. Methylglyoxal induces systemic symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. PloS one 9, e105307, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105307 (2014).

Portalatin, M. & Winstead, N. Medical management of constipation. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery 25, 12–19, doi:10.1055/s-0032-1301754 (2012).

Turroni, F., van Sinderen, D. & Ventura, M. Bifidobacteria: from ecology to genomics. Frontiers in bioscience 14, 4673–4684 (2009).

Roager, H. M. et al. Colonic transit time is related to bacterial metabolism and mucosal turnover in the gut. Nature microbiology 1, 16093, doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.93 (2016).

Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26, 2460–2461, doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 (2010).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic acids research 41, D590–596, doi:10.1093/nar/gks1219 (2013).

Lozupone, C. & Knight, R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 71, 8228–8235, doi:10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005 (2005).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169, doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the EU Joint Programming Initiative – A Healthy Diet for a Healthy Life (JPI HDHL, http://www.healthydietforhealthylife.eu/) to MV and DvS, and the MIUR to MV. We thank GenProbio srl for financial support of the Laboratory of Probiogenomics. LM is supported by Fondazione Cariparma, Parma, Italy. DvS is a member of The APC Microbiome Institute funded by Science Foundation Ireland (SFI), through the Irish Government’s National Development Plan (Grant number SFI/12/RC/2273). Part of this research is conducted using the High Performance Computing (HPC) facility of the University of Parma.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.V. and T.M. conceived the study. A.T. and A.N. collected the samples and medical interpretation of the results. F.T., M.M. and A.V. performed libraries preparation and illumina sequencing. L.M., C.M., G.A.L. and D.v.S. performed the bioinformatics analyses and collaborated for the microbiological interpretation of the results. L.M., C.M., A.T., M.V., T.M. and D.v.S. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mancabelli, L., Milani, C., Lugli, G.A. et al. Unveiling the gut microbiota composition and functionality associated with constipation through metagenomic analyses. Sci Rep 7, 9879 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10663-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10663-w

This article is cited by

-

Effects of the increased protein level in small intestine on the colonic microbiota, inflammation and barrier function in growing pigs

BMC Microbiology (2022)

-

Intestinal AMPK modulation of microbiota mediates crosstalk with brown fat to control thermogenesis

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Targeting intestinal flora and its metabolism to explore the laxative effects of rhubarb

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2022)

-

In vitro Intervention of Lactobacillus paracasei N1115 Can Alter Fecal Microbiota and Their SCFAs Metabolism of Pregnant Women with Constipation and Diarrhea

Current Microbiology (2022)

-

Gut microbiota: a new avenue to reveal pathological mechanisms of constipation

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.