Abstract

This paper addresses the fabrication of vertically aligned ZnO@TiO2 multishell nanotubes by a combined full vacuum-plasma approach at mild temperatures. The growth is carried out within the premises of a one-reactor approach, i.e. minimizing the number of vacuum chambers and sample transferences. In this way, the interface between ZnO and TiO2 is fully preserved from humidity thus increasing ZnO durability and stability. These nanostructures are studied by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy in STEM (EDX-STEM). High density one-dimensional arrays of these nanotubes formed on FTO substrates are applied as photoanode in a dye-sensitized solar cell (DSC). The evolution of the dye adsorption capacity and solar cells parameters are explored as a function of the crystallinity and thickness of the TiO2 shell. The results show the critical effect of a full coverage by TiO2 of ZnO core to explain the mixed results found in the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In a recent work, we addressed the fabrication of ZnO nanotubes by an all-vacuum template procedure1. The protocol involves 3 basic steps: (i) growth of single crystal organic nanowires (ONWs) by Physical Vapor Deposition (OPVD)2 acting as supported 1D templates; (ii) formation of a metal oxide shell by Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition (PECVD)3, 4 and, (iii) sublimation of the organic template to yield metal oxide nanotubes. We aim herein to extend the potential of the developed protocol for the fabrication of multishell ZnO@TiO2 nanotubes. Critical advantages of this methodology are its general character from the point of view of both substrates and shells materials and nanostructure, mild experimental conditions for organic template and shell deposition as well as template removal. In addition, this protocol allows the application of a one-reactor approach, i.e. minimizing the number of vacuum/plasma chambers and transferences and thus avoiding exposure of the different layers/shells to air. We borrow this name from synthetic chemistry where there is a trend towards coupling several steps of a multi-step chemical reaction into just one reactor. This one-pot strategy is of high interest for the chemical industry due to economic and environmental advantages5. In this way, a methodology integrating sequential and/or simultaneous fabrication/processing steps without the necessity of exposing clean surfaces to ambient conditions and minimizing transfer between chambers can be regarded as one-reactor strategy. This approach provides an unparalleled accurate control on the interfacial composition of sequentially deposited materials including sharp interfaces between two photofunctional metal oxides such as ZnO and TiO2, preserving the surfaces and interfaces and reducing the use of solvents. In order to show these promising advantages, we will thoroughly characterize the ZnO@TiO2 NTs system by advanced scanning and transmission electron microscopies allowing a unique and deeper insight into the distribution of materials at the nanoscale, the state and sharpness of the interfaces and, degree of conformality of the shell(s)1, 6, 7.

In the second part of the article, we will demonstrate the stability of the NTs under room conditions and their straightforward implementation into photoelectric devices showing the fabrication of ZnO@TiO2 dye-sensitized solar cells.

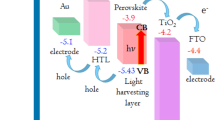

Dye-sensitized solar cells (DSCs) efficiency has slowly improved from 10% to 13% in a time lapse of 20 years8, 9. New ruthenium-free dyes and combination of dyes have been introduced in order to enhance light harvesting (boosting the photocurrent) while in conjunction with novel Co(II/III) electrolytes a parallel increase of the photovoltage has been favored10. Furthermore, a great deal of research has been carried out to optimize the photoanode of DSCs through the choice of the active material and its nanostructuration. In this regard, two main active photoanode materials have been widely studied for this application: ZnO and TiO2 5, 11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Bulk wurtzite ZnO has a direct band gap of 3.44 eV and n-type behavior. Even if the causes for such a n-type behavior are still unclear, it is speculated that the unintended incorporation of impurities such as H would be a possible explanation18. The high bulk electron mobility of ZnO, μe = 200 cm2V−1s−1, and acceptable exciton binding energy of 60 meV make it an attractive candidate for its potential implementation in DSCs13, 14, 19, 20. However, its known degradation by many usual dyes, its instability in aqueous solution and the poor charge-separation potential (injection) at the dye/oxide interface, limit the overall cell performance and operation lifetime21. On the other hand, TiO2 was the first choice for DSCs since it is chemically stable and it possesses an injection efficiency of 100%, twice that of ZnO. Moreover, bulk TiO2 has a band gap of 3.2 eV for the anatase phase and like ZnO it is also an n-type semiconductor due to oxygen vacancies and the presence of Ti3+ cations8, 22. The major drawbacks associated with TiO2 are its low electron mobility, ranging from 1 cm2V−1s−1 for amorphous TiO2 to 30 cm2V−1s−1 for anatase, and its relatively low exciton binding energy of 4 meV23, 24.

The superior performance of these 1D ZnO nanostructures in DSCs when compared to mesoporous thin films of the same material was demonstrated by Law et al.25 and adjudged to the intrinsic higher specific area of the 1D material. Although ZnO NTs effectively outperformed their thin film counterpart, the already mentioned poor chemical stability of ZnO certainly limits its use in DSCs regardless of the microstructure/nanostructure. In an attempt to hinder its degradation, several researchers have placed their efforts in the synthesis of ZnO@TiO2 core@shell nanostructures for DSCs, generally obtaining mixed results26,27,28,29,30,31. In fact, Yang et al. unraveled the unexpected long-term instability of ZnO nanowires protected by a TiO2 shell formed by atomic layer deposition (ALD)32. They showed an enhanced photoetching and self-induced photocorrosion of c-(0001) oriented ZnO/TiO2 NWs stored under ambient conditions and exposed to UV-light. In our case, the polycrystalline character of the ZnO shell will play an advantageous role in the stability of the ZnO-TiO2 interface. Thus, we have prepared 1D-based DSCs comprising ZnO NTs covered with a TiO2 shell following the same multi-step produce described above and investigated the effect of this outer shell crystallinity and thickness on the cell performance. Moreover, a potential explanation to the observed discrepancies in the literature concerning ZnO@TiO2-based DSCs is given.

Results and Discussion

Advanced Characterization of the Multishell Nanotubes

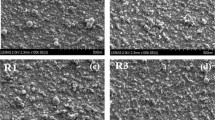

Figure 1 shows the density (Fig. 1a), preferential vertical alignment (Fig. 1b) and microstructure (Fig. 1b) of 250 nm wall thickness ZnO NTs coated with a 50 nm equivalent thin film thickness of anatase (ZnO@50 nm anatase NTs). Note that equivalent thin film thickness refers to the same amount of material obtained in the absence of NWs as in Figure S1a–c. The porous nature of the equivalent thin film can be appreciated in Figure S1a–c in the Supplementary Information. For comparison a thicker ZnO NT also grown at room temperature (Fig. 1d) and an anatase NT grown at 250 °C (Fig. 1e), both of 600 nm equivalent thin film thickness, are shown. Even for higher thicknesses the ZnO exhibits a columnar microstructure (Fig. 1d) while anatase NTs present clear crystalline facets (Fig. 1e). The TiO2 coated ZnO NTs present a columnar microstructure regardless of the thickness of the TiO2 layer (in the 5–50 nm studied range) or the crystalline character of this outer layer. For the sake of simplicity, TiO2 deposited at room temperature will be referred as meso-TiO2, which is amorphous as shown by Borrás et al.33.

The stability and crystallinity of ZnO@TiO2 was studied by means of HRTEM, finding that the as-prepared samples stored under ambient conditions for roughly 2–3 months showed no indication of degradation of the inner ZnO as observed by Yang et al.32. As evidenced in Fig. 2a for a ZnO@50 nm anatase NT, the ZnO core is preserved and even its polycrystalline nature is still evident from the fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the selected areas in Fig. 2b, which gives plane distances of 2.81 Å and 2.62 Å, matching the ZnO wurtzite planes (100) and (002), respectively, in line with our previous results1. On the other hand, according to the calculated plane distance of 2.43 Å from FFT in Fig. 2c, anatase tends to crystallize preferentially in the (004) direction. This indicates that anatase TiO2 is formed exposing {001} facets which have been recently demonstrated to enhanced the photocatalytic activity and efficiency in dye-sensitized solar cells based on anatase nanoparticles34, 35.

The evolution of the meso-TiO2 (grown at room temperature) or anatase (grown at 250 °C) coverage of a ZnO NT was investigated by STEM-EDX as shown in Fig. 3. The thickness of TiO2 shell was limited to 50 nm due to the final application pursued in this work. The integrity of the ZnO core is again demonstrated by the EDX map in Fig. 3a for a ZnO@50 nm-meso-TiO2 NT, whereas the map in Fig. 3b represents the total oxygen bonded to Zn and Ti. The EDX maps of titanium for ZnO@meso-TiO2 with TiO2 shells between 5–50 nm are presented in Fig. 3c–e. Note that the intensity scale of each EDX map in Fig. 3c–e is proportional to the amount of TiO2 present in the NTs (the measurements were performed under identical conditions), going from a maximum value of 10 for 5 nm (Fig. 3c) to more than 400 for 50 nm (Fig. 3e) of TiO2. Furthermore, these EDX maps were practically the same for anatase, data not shown here. With a layer only 5 nm thin (Fig. 3c), the intensity of Ti in the EDX maps is extremely low, revealing that the deposition occurred preferentially at the top due to self-shadowing effects as reported by Macias-Montero et al.3. Owing to this low TiO2 coverage, most of the ZnO is expected to be exposed to the environment. In the case of 20 nm (Fig. 3d), there are only a few regions in the NT with zero to very low intensity (dark blue in the color scale), meaning that almost no ZnO will be directly exposed. For 50 nm (Fig. 3e) a continuous layer of TiO2 is formed, hindering the direct contact between ZnO and the environment. It must not be forgotten that both meso-TiO2 and anatase are porous materials, so it is expected that both electrolyte and dye in a DSC diffuse to and into ZnO. However, due to this TiO2 coverage, it is also expected that this effect is diminished.

Dye loading capabilities of ZnO-TiO2 systems

In order to investigate the influence of the multishell in the adsorption capacity, several adsorption-desorption experiments were conducted in the corresponding single layers TFs of ZnO, meso-TiO2 and anatase. From Figure S2 it is clear that the dye intake ability of ZnO was limited, perhaps due to the lower dye immersion time used to avoid damaging the oxide nanostructure. Meso-TiO2 performed much better, but it was greatly surpassed by anatase. Note that even though anatase and meso-TiO2 films were thicker, these conclusions will still be valid for thinner films since the absorption curves were normalized with respect to thickness. However changes in the porosity as a function of thickness cannot be completely ruled out.

In the case of multilayers of ZnO/TiO2 it was found that the addition of a TiO2 layer (both meso-TiO2 and anatase) to 250 nm ZnO significantly enhanced the dye loading capability of the films. Moreover, the effect resulted more pronounced in anatase than in amorphous meso-TiO2 as observed in the UV-Vis spectra from Figure S3. Table 1 gathers the obtained dye concentrations for the different multilayers (readers are referred to the SI section for the concentration determination procedure, see also Fig. S4 for the N719 concentration calibration curve). It is remarkable that the combination of ZnO and TiO2 (both meso-TiO2 and anatase) boosted the dye load in the films. Looking at the obtained concentrations in the table, three observations can be made. First, all ZnO/TiO2 (both meso-TiO2 and anatase) films were able to adsorb more dye than pure ZnO films. Secondly, anatase seemed to work better than meso-TiO2 in the ZnO/TiO2 system. Lastly, an increase in the thickness of the TiO2 films (both meso-TiO2 and anatase) gave rise to an increment in dye surface concentration (Table 1), which may be due to the particular evolution of the TiO2 microstructure with the thickness along with a higher surface area due to size increase of the NTs.

Due to severe limitations in the desorption of N719 from NTs (the films did not release all the dye), integrating sphere measurements were performed in ZnO samples covered with anatase (Fig. 4a), meso-TiO2 (Fig. 4b), and ZnO coated with 50 nm of anatase. Results are included in Fig. 4c to compare qualitatively the dye loading in thin film and nanotubes. The maximum observed in Fig. 4a–c, shifted from its position in solution (Fig. S3), is in good agreement with the determined absorption spectrum of N719 on TiO2 36. It is clear from Fig. 4d, that NTs can increase substantially the dye loading by offering a much higher surface area as already observed for pure anatase systems. Moreover, this difference in dye concentration was readily noticeable at the naked eye as in Fig. 4b; the thin film samples possess a barely appreciable color whereas in NTs the dyed film is highly apparent.

ZnO-TiO2 Dye sensitized solar cells

The main photovoltaic parameters of the fabricated DSCs depicted in Fig. 5a) are listed in Table 2. At first glance, the incorporation of a TiO2 shell was detrimental for the cell performance, giving rise to remarkably lower photocurrents compared to bare ZnO, in spite of the fact that the multishells showed a more intense dye adsorption capacity. However, the photovoltage became enhanced, which shows that the TiO2 shell does indeed improve the charge separation capability at the oxide/dye/electrolyte interface. This is a well-known fact related to the dielectric properties of both oxides14, 37. That the photoconversion process is now determined by the TiO2/dye/electrolyte system rather than by the ZnO/dye/electrolyte one, explains why the photovoltage, which is a direct measure of charge separation, is greater and basically the same regardless the thickness of the cell. Despite these promising features, the photocurrent worsened when the thickness was increased. This indicates that amorphous TiO2 is not a good electron conducting material, which also explains the lower fill factor due to high series resistance. As a matter of fact, when the shell is made of the anatase material, which is a more efficient electron conductor, not only the photovoltage but also the photocurrent is larger. Thin films with 50 nm of meso-TiO2 and anatase have been measured as references. These devices produced a much lower photocurrent due to lower light harvesting, as shown in Fig. 4c.

Furthermore, we can trace the origin of the low performance of the ZnO-TiO2 system by calculating the theoretical J SC of the NT electrodes with the adsorbed dye via Equation 1

where λ min and λ max define the wavelength range and I 0 is the AM1.5 solar flux. The IPCE can be expressed as the product of the efficiency of the processes involved in the electrical conversion in DSC as in Equation 2

where η lh (λ) is the light-harvesting efficiency of the sensitized oxide layer η inj (λ) is the electron injection efficiency from the sensitizer to the oxide, and η col (λ) is the electron collection efficiency (dye regeneration efficiency is implicitly included in the injection term). Assuming 100% injection and collection efficiency it is possible to calculate the theoretical J SC from the light absorption data in Fig. 4. In this calculation it is also implicitly assumed that there are no losses due to reflection and absorption of the electrolyte. However, they are expected to be small and affect all samples in the same extent. Results are shown in Table ST1.

It is observed that the theoretical current is almost one order of magnitude larger that the experimental one. This indicates that the main loss in current is due to low injection and strong recombination. We also observe that anatase samples are more efficient in harvesting light, which explains the relatively larger photocurrents. In any case the results demonstrate that higher currents are potentially extractable from this kind of samples.

According to the energy diagram in Fig. 5, the conduction bands of ZnO and TiO2, and thus their respective Fermi levels, are generally considered to be aligned. However, the results indicate that the electronic transfer between TiO2 and ZnO is hindered due to the existence of a small energy barrier26. Owing to this lack of electronic transfer between TiO2 and ZnO, the photovoltaic response seems to be originated primarily from the ZnO cores, although a beneficial effect of the TiO2 core is observed in the photovoltage, possibly due to a blocking of recombination as explained above.

Comparing with results from the bibliography where core@shell nanostructures of the type ZnO@TiO2 have been synthetized and used in DSCs27, 30, 31, 38, 39, here the relatively thick ZnO blocking layer, which also acts as seed for the growth of the organic NWs (see methods), hinders any kind of direct contact between TiO2 and the photoanode, i.e. the photogenerated electrons in the TiO2 must travel through the ZnO first, and as mentioned before, if charge transfer from TiO2 to ZnO is hindered, then it is reasonable no to expect a photovoltaic improvement as observed. In the previous mentioned references27, 30, 31, 38, 39, both ZnO and TiO2 were at least partially in contact with the photoanode, observing an improvement of the performance of the cells. Nonetheless, it has been reported that only in the case of ultrathin ZnO blocking layers ( < 20 nm) there is an improvement in the overall efficiency of the cells, observing a deterioration of the photovoltaic performance with only 20 nm thick ZnO blocking layers29. Despite ZnO was grown by atomic layer deposition, even with this technique ZnO may present an island-like or columnar growth depending on the substrate and deposition conditions40, 41. This further supports our argument that for highly porous or quite thin layers of ZnO or TiO2, where both oxides are in contact with the photoanode, a general enhancement of the cells is most likely to occur due to the contribution of both oxides, while if only one of the oxides is contacting the photoanode, then a degradation of the efficiency is usually noticed. These general observations explain the discrepancies commonly observed in the literature.

Conclusion

Vertically aligned multishell ZnO@TiO2 NTs with a high degree of conformality of each layer have been fabricated by a whole vacuum procedure. The exposed methodology allowed us to tune the chemical composition, crystallinity and thickness of the NTs which were implemented as photoanodes in DSCs. Moreover, the ability of the supported NTs to withstand the cells fabrication process demonstrated their robustness.

Mixed results were obtained for amorphous and crystalline TiO2, however, it has been found that the addition of a thin TiO2 shell turned out to be detrimental for the performance of the cells, decreasing the maximum attainable photocurrent but increasing the Open-circuit Voltage (VOC) for both amorphous and anatase shells. However, thicker anatase shells improve the value of VOC up to a value of 635 mV for a 50 nm shell, whereas this parameter decreased monotonically with thicker meso-TiO2 NT walls up to a value of 460 mV (higher than that of bare 250 nm ZnO NTs). This behavior was explained in terms of the apparent negligible electronic transference between ZnO and TiO2, which taking into account the nature of the blocking layer and growth of both semiconductor oxides also explains the frequent discrepancies found in literature.

The fabrication of ZnO@TiO2 NTs presented here can be easily extended to other metal oxides by selecting the organometallic/metal-organic precursors. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that with the deposition methodology developed in this work, ZnO@TiO2 nanotubes with stable interfaces can be produced, paving the way for a broader range of applications such as photocatalysis, UV absorbers and antibacterial surfaces.

Methods

The fabrication of the nanostructured photoanodes comprised a full-vacuum multi-step procedure which can be conveniently divided into three main steps as described in refs 1, 3.

Growth of ONWs by OPVD

ONWs were grown on a thin film of ZnO or TiO2 (amorphous or anatase) previously deposited by PECVD on FTO coated glass substrates. Polished n-type Si(100) purchased from Topsil and fused silica from Sico Technology GmbH were used in each preparation for later characterization. The organic Phthalocyanine (H2Pc) was supplied from Aldrich and used as received without further purification. The OPVD procedure for the formation of single crystal ONWs has been fully described in refs 1,2,3, 42. It consists on the sublimation of the organic molecules from a Knudsen cell at 0.02 mbar of Ar using a growth rate about 0.3 Å/s and controlled substrate temperature. The substrates temperature was settled at ~230 °C for H2Pc. The nominal thickness of the NWs was set to 0.65 kÅ which corresponds to NWs 2–3 μm long.

Growth of ZnO and TiO2 layers by PECVD

Both semiconducting oxides, ZnO and TiO2, were fabricated by PECVD in a microwave (2.45 GHz) ECR reactor with a down-stream configuration as described in ref. 1. Diethylzinc (ZnEt2) and titanium tetraisopropoxide (TTIP) were utilized as precursors (Sigma Aldrich). Crystalline ZnO was grown at RT with oxygen as plasma gas. Total pressure in the chamber was settled at 1.5 × 10−2 mbar and plasma power at 400 W. meso-TiO2 was grown at the same conditions with a slightly lower pressure (8.6 × 10−3 mbar). Anatase thin films and nanotubes were prepared as meso-TiO2 but heating the substrates at 250 °C during the fabrication process. In both cases the thickness of the ZnO was fixed to 250 nm and three different TiO2 thicknesses were employed: 5 nm, 20 nm and 50 nm. Thin films of TiO2 (amorphous or anatase)/ZnO grown under identical conditions to the nanotubes but avoiding the ONW template have been used as references and will be referred here as TF(s).

Empty of the 1D nanostructures

Under standard conditions a heating treatment at 350 °C and 10−6 mbar of pressure was applied to these samples for 3 hours to achieve a complete emptying of the inner organic core. No alteration of the vacuum was detected during the process. After the annealing process is performed, the samples were allowed to cool down in high vacuum avoiding water condensation in the highly porous nanotube walls.

Solar cells fabrication procedure

Counter electrodes. FTO/glass substrates of 2.5 × 2 cm2 provided by Xop Glass (12–14 Ω/γ) were drilled in two points for later electrolyte injection, rinsed with acetone, isopropanol and absolute ethanol and heated to 500 °C for 1 hour. 12 μL of plastisol (Solaronix) are dispersed on the substrates, dried in air and heated in a furnace for 20′ at 400 °C.

Working electrodes. FTO/glass substrates were cleaned just as the counter electrodes. An active area of 0.7 cm2 was defined with an aluminum foil mask and a layer of less than 100 nm of ZnO was deposited by PECVD. This ZnO film acts as a hole blocking layer and provides the necessary roughness for the growth of ONWs. ZnO NTs with different thicknesses were fabricated by PECVD onto the FTO electrode through a mask to delimitate a covered area of 7 × 10 mm2. Samples were heated up to 120 °C before immersing in the dye solution, 0.5 mM solution of N719 dye (cis-diisothiocyanato-bis(2,20-bipyridyl-4,40-dicarboxylato) ruthenium(II) bis (tetrabutylammonium)) [purchased from Solaronix] in ethanol, to prevent adsorption of air moisture. The immersion time was limited to 1 hour in all cases.

Electrolytic solution. It was prepared by addition of 0.6 M 1,2-dimethyl-3-propylimidazole iodine (DMPII), 0.1 M LiI, 0.5 M 4-tertbutyl-pyridine (TBP), 0.05 M I2 and 0.1 M guanidinium thiocyanate (GuSCN) to a mixture of acetonitrile/valeronitrile (85/15).

Sealing of the cells. A frame of a thermoplastic polymer (Surlyn, Solaronix) was placed on the perimeter of the active area and then sandwiched with the counterelectrode. The whole cell was heated to 140 °C under slight pressure to ensure a proper sealing. After that the electrolyte was injected and the holes on the counterelectrode sealed with Surlyn and a cover slide glass.

Dye N719 concentration determination

A calibration curve was constructed by measuring the absorbance between 200 and 900 nm of four solutions of dye N719 in KOH 1 M in MeOH, being the molar concentration of the dye in each case 1 × 10−6, 5 × 10−6, 5 × 10−5 and 1 × 10−4. Using the Lambert-Beer’s law, the absorption coefficient ε (M−1cm−1) can be calculated by taking the absorbance at 515 nm. In this case, a straight line with R2 = 0.997 was obtained by linear regression, estimating a value of 11331 ± 276 for ε. With this value and a known value of 1 cm for the light path, the molar volume concentration was calculated for each sample. The total number of moles for each film was calculated by multiplying the obtained concentration by the volume of solution employed (2 ml). Then, the surface concentration was calculated by dividing this value by the area of the sample (1.875 cm2). Finally, the normalized surface concentration is simply this value divided by the thickness of the layer.

A precision quartz cell from Hellma with a light path of 1 cm and a Cary 100 spectrometer from Varian were used for these experiments.

The UV-Visible spectra of dye-sesitized electrodes were measured using an integrating sphere (Mikropack, ISP-50–8-R-GT) in the range 350–700 nm

Experimental characterization methods

The solar-cell devices were characterized using a solar simulator with an AM1.5 G filter (ABET). A reference solar cell with temperature output (Oriel, 91150) was used for calibration.

SEM micrographs were acquired in a Hitachi S4800 working at 2 kV. The samples were dispersed onto Holey carbon films on Cu or Ni grids from Agar scientific for TEM characterization. EDX maps were acquired with a FEI Tecnai Osiris TEM/STEM 80–200 working at 200 kV. Post-processing of EDX data was performed with the open source Hyperspy software: hyperspy.org. as described elsewhere7. HAADF-STEM and HRTEM were carried out with both Osiris and FEI Tecnai G2F30 S-Twin STEM microscope also working at 200 kV.

References

Filippin, A. N. et al. Vacuum template synthesis of multifunctional nanotubes with tailored nanostructured walls. Sci. Rep. 6, 20637 (2016).

Borras, A., Gröning, O., Aguirre, M., Gramm, F. & Gröning, P. One-Step Dry Method for the Synthesis of Supported Single-Crystalline Organic Nanowires Formed by π-Conjugated Molecules. Langmuir 26, 5763–5771 (2010).

Macias-Montero, M. et al. Vertically Aligned Hybrid Core/Shell Semiconductor Nanowires for Photonics Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 5981–5989 (2013).

Filippin, A. N. et al. Plasma assisted deposition of single and multistacked TiO2 hierarchical nanotube photoanodes. Nanoscale 9, 8133–8141 (2017).

Martinson, A. B. F., Elam, J. W., Hupp, J. T. & Pellin, M. J. ZnO Nanotube Based Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Nano Lett. 7, 2183–2187 (2007).

Leary, R. K. & Midgley, P. A. Analytical electron tomography. MRS Bull. 41, 531–536 (2016).

Burdet, P., Saghi, Z., Filippin, A. N., Borrás, A. & Midgley, P. A. A novel 3D absorption correction method for quantitative EDX-STEM tomography. Ultramicroscopy 160, 118–129 (2016).

O’Regan, B. & Grätzel, M. A low-cost, high-efficiency solar cell based on dye-sensitized colloidal TiO2 films. Nature 353, 737–740 (1991).

Mathew, S. et al. Dye-sensitized solar cells with 13% efficiency achieved through the molecular engineering of porphyrin sensitizers. Nat. Chem. 6, 242–247 (2014).

Upadhyaya, H. M., Senthilarasu, S., Hsu, M.-H. & Kumar, D. K. Recent progress and the status of dye-sensitised solar cell (DSSC) technology with state-of-the-art conversion efficiencies. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 119, 291–295 (2013).

Tan, B. & Wu, Y. Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells Based on Anatase TiO2 Nanoparticle/Nanowire Composites. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 15932–15938 (2006).

Ranjusha, R., Lekha, P., Subramanian, K. R. V., Shantikumar, V. N. & Balakrishnan, A. Photoanode Activity of ZnO Nanotube Based Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 27, 961–966 (2011).

Xu, F. & Sun, L. Solution-derived ZnO nanostructures for photoanodes of dye-sensitized solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 818–841 (2011).

Anta, J. A., Guillén, E. & Tena-Zaera, R. ZnO-Based Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 11413–11425 (2012).

Yan, X., Feng, L., Jia, J., Zhou, X. & Lin, Y. Controllable synthesis of anatase TiO2 crystals for high-performance dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 5347–5352 (2013).

Roh, D. K., Chi, W. S., Jeon, H., Kim, S. J. & Kim, J. H. High Efficiency Solid-State Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells Assembled with Hierarchical Anatase Pine Tree-like TiO2 Nanotubes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 379–386 (2014).

Wu, W.-Q., Xu, Y.-F., Su, C.-Y. & Kuang, D.-B. Ultra-long anatase TiO2 nanowire arrays with multi-layered configuration on FTO glass for high-efficiency dye-sensitized solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 644–649 (2014).

Janotti, A., Van de, W. & Chris, G. Fundamentals of zinc oxide as a semiconductor. Rep. Prog. Phys. 72, 126501 (2009).

Look, D. C. et al. Electrical properties of bulk ZnO. Solid State Commun. 105, 399–401 (1998).

Solar Cells - Dye-Sensitized Devices (InTech, 2011).

Soga, T. Nanostructured Materials for Solar Energy Conversion (Elsevier, 2006).

Thin Film Structures in Energy Applications (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

Forro, L. et al. High mobility n‐type charge carriers in large single crystals of anatase (TiO2). J. Appl. Phys. 75, 633–635 (1994).

Tiwana, P., Docampo, P., Johnston, M. B., Snaith, H. J. & Herz, L. M. Electron Mobility and Injection Dynamics in Mesoporous ZnO, SnO2, and TiO2 Films Used in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. ACS Nano 5, 5158–5166 (2011).

Law, M., Greene, L. E., Johnson, J. C., Saykally, R. & Yang, P. Nanowire dye-sensitized solar cells. Nat. Mater. 4, 455–459 (2005).

Manthina, V., Correa Baena, J. P., Liu, G. & Agrios, A. G. ZnO–TiO2 Nanocomposite Films for High Light Harvesting Efficiency and Fast Electron Transport in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 23864–23870 (2012).

Zhao, R. et al. ZnO/TiO2 core–shell nanowire arrays for enhanced dye-sensitized solar cell efficiency. Appl. Phys. A 113, 67–73 (2013).

Chen, L.-C. et al. Preparation of Vertically Aligned ZnO/TiO2 Core-Shell Composites for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells, Preparation of Vertically Aligned ZnO/TiO2 Core-Shell Composites for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Int. J. Photoenergy Int. J. Photoenergy 2013 2013, e417964 (2013).

Ding, J. et al. The influence of anatase-rutile mixed phase and ZnO blocking layer on dye-sensitized solar cells based on TiO2nanofiberphotoanodes. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 8, 9 (2013).

Lu, H., Tian, W., Guo, J. & Li, L. Interface Engineering through Atomic Layer Deposition towards Highly Improved Performance of Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Sci. Rep. 5, 12765 (2015).

Polkoo, S. S., Saievar-Iranizad, E. & Bayatloo, E. Fine designing 3-dimensional ZnO nanowalls with TiO2 nanoparticles for DSSC application. Appl. Phys. A 119, 1269–1276 (2015).

Yang, Y. et al. Unexpected Long-Term Instability of ZnO Nanowires ‘Protected’ by a TiO2 Shell. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 13920–13921 (2009).

Borrás, A., Cotrino, J. & González-Elipe, A. R. Type of Plasmas and Microstructures of TiO2 Thin Films Prepared by Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 154, P152–P157 (2007).

Chu, L., Qin, Z., Yang, J. & Li, X. Anatase TiO2 Nanoparticles with Exposed {001} Facets for Efficient Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Sci. Rep. 5, 12143 (2015).

Ye, L. et al. Synthesis of anatase TiO2 nanocrystals with {101}, {001} or {010} single facets of 90% level exposure and liquid-phase photocatalytic reduction and oxidation activity orders. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 10532–10537 (2013).

De Angelis, F., Fantacci, S., Mosconi, E., Nazeeruddin, M. K. & Grätzel, M. Absorption Spectra and Excited State Energy Levels of the N719 Dye on TiO2 in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell Models. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 8825–8831 (2011).

Idígoras, J. et al. The Impact of the Electrical Nature of the Metal Oxide on the Performance in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells: New Look at Old Paradigms. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 3931–3944 (2015).

Park, K. et al. Effect of an Ultrathin TiO2 Layer Coated on Submicrometer-Sized ZnO Nanocrystallite Aggregates by Atomic Layer Deposition on the Performance of Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 22, 2329–2332 (2010).

Lei, J. et al. ZnO@TiO2 Architectures for a High Efficiency Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell. Electrochimica Acta 171, 66–71 (2015).

Cheun, H. et al. Electrical and Optical Properties of ZnO Processed by Atomic Layer Deposition in Inverted Polymer Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 20713–20718 (2010).

Baji, Z. et al. Nucleation and Growth Modes of ALD ZnO. Cryst. Growth Des. 12, 5615–5620 (2012).

Mbenkum, B. N., Barrena, E., Kelsch, M. & Dosch, H. Selective Growth of Organic 1-D Structures on Au Nanoparticle Arrays. Nano Lett. 6, 2852–2855 (2006).

Cao, G., Zhang, Q. & Brinker, C. J. Annual Review of Nano Research. 3, (WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2009).

Liu, J. et al. Enhanced photoconduction of free-standing ZnO nanowire films by L-lysine treatment. Nanotechnology 21, 485504 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Junta de Andalucia (FQM 1851 and FQM-2310) and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and Agencia Estatal de Investigación (MAT2016–79866-R, MAT2013–42900-P, MAT2013–47192-C3-3-R, MINECO-CSIC 201560E055 and Red de Excelencia “Emerging photovoltaic Technologies”) and the EU through cohesion fund programs for financial support. JRSV and Angel B acknowledge Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions H2020-MSCA-IF-2014 PlasmaPerovSol grant (Project ID 661480).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N.F. carried out the synthesis of the multishell nanotubes,dye-loading experiments and calculations with assistance of J.R.S.V. M.M.M. performed the characterization by SEM and XRD. Z.S. and P.B. carried out respectively the HAADF-STEM and EDX acquisitions under supervision of P.M., J.I. and J.A.A. were responsible for the solar cell assembly and characterization. A. Barranco and A. Borras designed the experiments and wrote the main manuscript text with contributions from all authors. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Filippin, A.N., Macias-Montero, M., Saghi, Z. et al. One-reactor plasma assisted fabrication of ZnO@TiO 2 multishell nanotubes: assessing the impact of a full coverage on the photovoltaic performance. Sci Rep 7, 9621 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09601-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09601-7

This article is cited by

-

Solvent assisted evolution and growth mechanism of zero to three dimensional ZnO nanostructures for dye sensitized solar cell applications

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Vertically aligned TiO2/ZnO nanotube arrays prepared by atomic layer deposition for photovoltaic applications

Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.