Abstract

All-optical switches have been considered as a promising solution to overcome the fundamental speed limit of the current electronic switches. However, the lack of a suitable third-order nonlinear material greatly hinders the development of this technology. Here we report the observation of ultrahigh third-order nonlinearity about 0.45 cm2/GW in graphene oxide thin films at the telecommunication wavelength region, which is four orders of magnitude higher than that of single crystalline silicon. Besides, graphene oxide is water soluble and thus easy to process due to the existence of oxygen containing groups. These unique properties can potentially significantly advance the performance of all-optical switches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The concept of using all-optical switch - manipulate photons with photons - to avoid electro-optic conversion in optical communication networks is almost as old as the optical communication itself. Yet only recently has serious attention been given because in the past the innovation and breakthroughs in electronics were able to keep up with the relentless exponential growth of the Internet Protocol (IP) traffic1, 2. As the IP traffic continues to grow without foreseeable sign of halting, electronic devices are rapidly approaching their fundamental speed limit. It has been widely accepted that for switching speed above 100 GHz, all-optical switching is the only viable solution3.

To be deployed into optical communication networks, all-optical switches must satisfy the requirements in cost, size, weight, and power consumption (C-SWaP). Among all the material platforms that have been intensively investigated, silicon is the most potent candidate. The fabrication maturity of the silicon electronics industry can be leveraged to rapidly and cheaply create a large number of optical devices with incredible economies of scale. While recent breakthroughs in integrated silicon photonics4,5,6 have laid a solid foundation for photonic devices that can fulfill the C-SWaP prerequisites, the lack of a suitable third-order nonlinear material deters the development efforts. Silicon has relatively high third-order nonlinearities and its large refractive index facilitates the tight confinement of light inside the submicron single mode waveguide, leading to an extraordinarily high nonlinear parameter γ up to 3 × 102 W−1m−1 7, 8. γ is defined as n 2/(λA eff ), where A eff is the effective area of the waveguide, λ is the wavelength and n 2 the Kerr coefficient8. However, materials with large Kerr coefficients usually have small bandgap and therefore also have strong two-photon absorption (TPA) effect, which not only results in the loss of photons but also causes undesired free carrier absorption (FCA) and dispersion (FCD)9. The nonlinear figure of merit (FOM), defined as n2/(β λ), is used to quantize the intrinsic limitation, where β is the TPA coefficient. The FOM of silicon is only 0.3. A few materials have been investigated as alternatives such as amorphous silicon and silicon nitride7, 8. Although these materials have amazingly large FOM values, they suffer from small Kerr coefficient and hence result in power-hungry devices.

In recent years, there is growing interest in the optical nonlinearities of two-dimensional (2D) materials. Graphene shows a remarkable Kerr coefficient of ~102 cm2/GW at 1550 nm10, but it is accompanied by highly nonlinear absorption due to the zero bandgap. Thus, Graphene has been intensively studied as a promising saturable absorber11, 12. Black Phophorous (BP) has strong saturable absorption, but its Kerr effect is negligible13, 14. Few-layer oxidized Black Phosphorous (OBP) has a Kerr coefficient of ~10−2 cm2/GW13, 14. However, its nonlinear absorption is high. Bi2Se3 shows a nonlinear refractive index of 10 −1 cm2/GW at 800 nm15, but it is highly absorptive at telecommunication wavelength as its bandgap is ~0.3 eV. Recently, Graphene oxide (GO) has become a rising star in the graphene family due to its unique physical and chemical properties originated from the hybridization of the sp 2- and sp 3- carbon atoms. One intriguing property is that its optical and electrical properties can be tuned dynamically by manipulating the content and location of oxygen containing groups through either chemical or physical reduction16,17,18,19,20. A recent study on laser reduction unveils the potential of achieving a large nonlinear coefficient and large enough FOM simultaneously21. An n 2 of ~15 cm2/GW has been observed at 800 nm, which is more than five orders of magnitude larger than that of Silicon, while its FOM is as large as 4.5621. Its nonlinear properties are stable under high-power illumination up to 400 mJ/cm2, 22. Due to the existence of oxygen containing groups, GO is hydrophilic and water soluble, making it easy to process. Although numerous research activities have been reported, few are in the telecommunication wavelength range. In this paper, we report the ultrahigh third-order nonlinearity of the GO film synthesized with the vacuum filtration-and-transfer technology. The observed n 2 is four orders of magnitude larger than single crystal silicon with negligible high order absorption, which makes GO a promising candidate for all-optical switches in the telecommunication regime.

Results

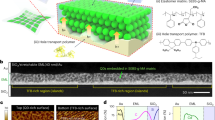

The GO films are synthesized by the chemical reduction of graphite via a modified Hummers method23. Firstly, graphite and NaNO3 are mixed with concentrated H2SO4. By vigorous stirring, the reducing agent –KMnO4 is added into the suspension. Then H2O2 is added into the mixture at 98 °C. The product is washed and dried, and then the GO sheets are obtained after the purification. For the self-assembly of GO sheets, a deionized water/methanol mixture with an optimal ratio of 1:5 is used to disperse GO. The GO thin films have been synthesized via the vacuum filtration method by using the schematic setup in Fig. 1(a) 24. The vacuum filtration process involves the filtration of a GO suspension through an anodic aluminium oxide (AAO) or polyethylene terephthalate (PET) membrane. As the liquid (water) passing through the membrane, the GO sheets are filtered on the membrane, forming the high quality GO thin films with desired thickness, as shown in Fig. 1(b) and Fig. 1(c). Then the filtrated highly uniform GO thin films on the membrane (Fig. 1(c)) can be transferred onto various substrates, such as the glass slide (Fig. 1(d)), by either dissolving the membrane or peeling off the film with the aid of water. Moreover, the nanoscale control over the film thickness can be achieved by simply varying either the concentration of the GO solution or the filtration volume.

(a) The schematic diagram of the filtration setup. (b) Schematics of the vacuum filtration process for the GO suspensions. (c) The filtrated GO thin films on the AAO membrane. (d) The transferred GO thin film on the glass substrate. (e) The AFM images and (f) the SEM image of the GO thin film on the glass substrate.

The thickness of the GO thin film is 1 μm and is transferred onto a 125 μm thick cover glass slide. Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) measurements show that the surface roughness is around 34 nm, as shown in Fig. 1(e). The scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the GO thin film is shown in Fig. 1(f). The linear absorption of the GO thin film is measured by the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). The absorption of GO is weaker at telecommunication wavelength compared to its absorption at the shorter wavelengths due to the smaller photon energy21. The Raman spectroscopy of the GO thin film can be found in ref. 21.

The third-order nonlinearity of the GO film at the telecommunication wavelength is measured with the z-scan system shown in Fig. 2(a). Calmar femtosecond laser with a pulse width of 67 fs and a repetition rate of 20 MHz is used as the light source. The spectrum of the pulse is ~ 40 nm wide and centers at 1560 nm. Light from the laser is collimated and split into two channels at a ratio of 90:10. The 10% of power is used to monitor the power fluctuation and avoid fake signals25. The power of the beam is controlled through a combination of a quarter wave plate, a half wave plate, and a polarization dependent splitter. An f = 60 mm bi-convex lens is used to focus the beam. The sample is mounted on a motorized stage. A 50:50 plate beam splitter is used to split the beam into the open and close channels. A Labview program is developed to synchronize the movement of the motorized stage and data collection. Since the surface roughness of the GO is large compared to semiconductor materials, e.g. silicon, a continuous-working (CW) laser is exploited as a low irradiance source for background scattering subtraction26. A detailed description of the z-scan system is provided in the method section.

The z-scan system (a) and the open aperture z-scan curves when the peak irradiance equals to (b) 0.38 GW/cm2, (c) 1.78 GW/cm2, (d) 3.20 GW/cm2, and (e) 4.68 GW/cm2. The red circles are experimental data and the blue curves are theoretical fittings. WP - waveplate, PDS - polarization dependent splitter, PIS - polarization independent splitter, PD - photodiode.

Both open and closed aperture z-scan curves have been taken under irradiances between 0.38 GW/cm2 and 4.63 GW/cm2. The representative open aperture z-scan curves are shown in Fig. 2(b–e). As GO contains sp 2 - clusters in insulating sp 3 - matrix, its nonlinear behavior is a complicate interplay of sp 2- and sp 3- domains19, 27. However, since sp 3- hybridization has an energy gap of 2.7~3.1 eV19, 27, which is larger than the energy of a single photon at the wavelength of 1.55 μm, the sp 2- hybridization plays a dominant role in forming the open aperture z-scan curve. The size of the localized sp 2- clusters determines the energy gap, and GO usually contains a range of different sizes. Therefore, the collective band structure has no signature features17, 27. The existence of 2~3 nm sp 2- clusters has been confirmed with multiple metrologies, which correspond to an energy gap of ~0.5 eV17, 21, 27,28,29. The optical absorption of electrons can be easily saturated, resulting in the depletion of the valence band21. As shown in Fig. 2(b), at an irradiance I 0 of 0.38 GW/cm2, prominent saturable absorption (SA) is observed. As the irradiance increases to 1.78 GW/cm2, the SA peak decreases, as shown in Fig. 2(c), suggesting the increment of the saturable intensity (I s ), which is an indication of the increase of sp 2 - and sp 3 - ratio induced by the reduction of GO to rGO. The reduction of GO creates new sp 2 - clusters, through removal of oxygen. The process could provide percolation pathways among the existing sp 2 - domains17. When I 0 = 3.20 GW/cm2, SA becomes negligible due to the ratio of sp 2 - and sp 3 - has reached a value that the electrons on the ground states cannot be further depleted, as shown in Fig. 2(d). When I 0 continues to increase, reverse saturable absorption (RSA) has been observed, as shown in Fig. 2(e), which is possibly due to the excited state absorption (ESA).

The closed aperture z-scan curves are shown in Fig. 3. As aforementioned, a low irradiance z-scan curve is measured as a reference to subtract the scattering induced fake signals25. The Iris aperture was set to 0.3. When I 0 = 0.38 GW/cm2, paramount self-focusing was observed, as shown in Fig. 3(a). The peak-valley modulation exceeds 16%. The observed nonlinear behavior is primarily due to the population redistribution of the π electrons, the free carriers of the sp 2- domain, and the bounded electrons and free carriers of the sp 3- matrix19. Due to the relatively high repetition rate of laser pulses, the z-scan process is accompanied by the reduction of GO. As a result, the closed aperture curve is asymmetric. The n 2 is estimated to be 0.45 cm2/GW, which is four orders of magnitude higher than that of single crystal silicon8. With a lower peak irradiance or a smaller repetition rate, a stronger and symmetric closed aperture curve can be observed. However, due to the detection limitation of our in-house z-scan system, it is difficult to observe the nonlinear response with low peak irradiance. When I 0 increases to 1.78 GW/cm2, the self-focusing effects are abated, which is believed to be induced by the reduction of GO. Subsequently, the n 2 decreases to 0.13 cm2/GW, yet it is still a few orders of magnitude larger than that of the single crystal silicon26. When the peak irradiance increases to 3.20 GW/cm2, the transition from valley-peak to peak-valley (self-defocusing) configuration occurs. The z-scan curve is very difficult to fit due to the co-existence of two distinct nonlinear responses. When I 0 further increases to 4.63 GW/cm2, the closed aperture z-scan curve changes to peak-valley configuration, indicating a negative n 2, which is a confirmation of the existence of the reduction and the change of sp 2-/sp 3- ratio. The n 2 is estimated to be −0.012 cm2/GW. The observed behavior is consistent with the previously reported nonlinear properties of graphene10, 21. Thus the nonlinear refractive index is mainly attributed to the sp 2- clusters after reduction.

Figure 4a summarizes the magnitude of the nonlinear responses of the GO thin film under different irradiances. Both the nonlinear refractive index n 2 and the nonlinear absorption coefficient β as a function of the irradiance I 0 are deduced by fitting the closed aperture and open aperture z-scan curves, respectively. For open aperture fittings, β eff is used to account the combined effects of SA and RSA19. Thus the FOM is defined as n2/(βeffλ) which is shown in Fig. 4b. The entire process can be separated into three stages. In stage I, n 2 is positive and β eff is negative. SA dominants the overall nonlinear response in the open channel. For peak irradiance less than 3 GW/cm2, the FOM is around 0.5. As the peak irradiance I 0 continues to increase, the absolute values of both n 2 and β eff decrease. The absolute value of FOM increases significantly to approximately 1.5. Stage II is the transition stage, in which the value of n 2 is difficult to estimate due to the co-existence of the self-focusing and the self-defocusing. The z-scan closed aperture curve does not show clear peak-valley or valley-peak configurations either. In Stage III, both n 2 and β eff change signs, indicating that the majority of sp 3- regions have been reduced.

Discussion

In Stage I, although the absolute value of FOM is close to that of silicon, β eff is negative, which indicates a prominent SA. One should note that β eff is an equivalent coefficient which combines the effects of SA and other nonlinear absorptions. Thus, the FOM cannot be reliably calculated with the formula provided in the introduction section. Since the majority of sp 2- clusters are around 3 nm, corresponding to a band gap around 0.5 eV, and the energy gap of the sp 3- hybridization is 2.7~3.1 eV, figure of merit (FOM), defined as n the nonlinear absorption in stage I is negligible. Thus, although its FOM is close to silicon in Stage I, GO is a very promising material for all-optical switches. When the peak irradiance increases to beyond 3 GW/cm2, the FOM increases significantly to ~1.5. However, n 2 decreases to 1.67 × 10−2 cm2/GW, more than one order of magnitude smaller than the value before reduction. In the transition stage (Stage II), due to the coexistence and competition of two distinguish nonlinear effects, there is no clear overall nonlinear effect observed in the closed aperture z-scan curve, and therefore GO in this stage is not suitable for all-optical switch applications. In Stage III, the FOM is similar as that of the Stage I. β eff is positive and a clear RSA is observed in the open channel z-scan curve. n 2 is small in this stage. Further reduction of the GO can possibly increase n 2, but the nonlinear absorption will increase simultaneously. Based on the analysis, GO in stage I is most promising for all-optical switching applications. Table 1 summarizes the nonlinear coefficients of materials compatible with semiconductor fabrication process. The n2 of GO is four orders of magnitude larger than c-Si.

To further improve the performance of GO for all-optical switching applications, sp 3-/sp 2- ratio should be further increased. Since the close channel z-scan curve changes from valley-peak to peak-valley configuration during the reduction process, the positive nonlinear coefficient roots in the sp 3- hybridization and negative in the sp 2-. Increasing sp 3-/sp 2- ratio not only increases the nonlinear effect but also reduces the linear absorption and nonlinear absorption. Besides, the sp 2- induced nonlinear refractive index is from carrier effects, the relaxation time of which is tens of picoseconds due to the bandgap of the sp 2- hybridization20. To achieve faster switching speed, sp 3- hybridization is highly preferred.

In summary, we investigated the third-order nonlinear properties of the GO film at 1550 nm wavelength range with a z-scan set-up. The results show an exceptionally high n 2, which is about four orders of magnitude larger than single crystalline silicon. In the meantime, the nonlinear absorption is negligible due to the large energy gap of the sp 3- hybridization. Due to the existence of oxygen containing groups, GO is hydrophilic and water soluble. Thus it can be easily applied as the cladding of existing all-optical switch structures, such as ring resonators, slot waveguides and photonic crystal cavity. These properties make GO a potent candidate for all-optical switches.

Methods

Z-Scan

Figure 2(a) shows the z-scan system built. The laser beam is collimated through a 7 mm collimator (Thorlab, F810FX-1550). A quarter wave plate (QWP, Thorlab WPG10M-1550) converts circular polarization into linear polarization. A half-wave plate (HWP, Thorlab WPH10M-1550) is used to rotate the linear polarization direction32. Together with the 50:50 polarization dependent splitter cube (PDS, Thorlab CM1-PBS254), the quarter wave plate is used as a tunable attenuator to control the irradiance. Another 90:10 polarization independent splitter (PIS, Thorlab BS030) is used to split 10% of the total power for system monitoring to avoid the fake nonlinear signals25. An f = 60 mm bi-convex lens (Thorlab LB1723-C) is used to focus the light beam. The sample is mounted on a motorized stage (Thorlab MTS25-Z8E). A 50:50 plate beam splitter (PBS, Thorlab BSW12R) is used to split the beam into two channels, open and close. In the open channel, an f = 60 mm bi-convex lens (Thorlab LB1723-C) is used to ensure the collection of all the power in this channel. A photodiode (PD#2 Newport 818IR) is exploited to monitor the power. To ensure the photodiode works at the linear response range, a 10 × attenuator is mounted in front of PD#2. In the close arm, an Iris aperture and another f = 60 mm bi-convex lens (Thorlab LB1723-C) are used to harvest all the light passing through the aperture. PD #3 is used to detect the power in the close arm. The signals from PD #1~3 are collected with a BNC board (National Instrument BNC2110) and PCI card (National Instrument PCIe-6321). A Labview program is developed to synchronize the movement of the motorized stage and data collection. Calmar femtosecond laser with a pulse width of 67 fs and a repetition rate of 20 MHz is used as the light source. The spectrum of the pulse is ~40 nm wide and centered at 1560 nm. Since the surface roughness of the GO is large compared to semiconductor materials, e.g. silicon, a continuous-working (CW) laser is exploited as a low irradiance source for background scattering subtraction26.

References

Essiambre, R. J. & Tkach, R. W. Capacity Trends and Limits of Optical Communication Networks. Proceedings of the Ieee 100, 1035–1055 (2012).

van Uden, R. G. H. et al. Ultra-high-density spatial division multiplexing with a few-mode multicore fibre. Nature Photonics 8, 865–870 (2014).

Covey, J. et al. All-optical switching with 1-ps response time in a DDMEBT enabled silicon grating coupler/resonator hybrid device. Opt Express 22, 24530–24544, doi:10.1364/OE.22.024530 (2014).

Xu, X. C. et al. Flexible Single-Crystal Silicon Nanomembrane Photonic Crystal Cavity. Acs Nano 8, 12265–12271 (2014).

Xu, X. C. et al. Complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor compatible high efficiency subwavelength grating couplers for silicon integrated photonics. Appl Phys Lett 101 (2012).

Subbaraman, H. et al. Recent advances in silicon-based passive and active optical interconnects. Opt Express 23, 2487–2510 (2015).

Leuthold, J., Koos, C. & Freude, W. Nonlinear silicon photonics. Nat Photon 4, 535–544 (2010).

Moss, D. J., Morandotti, R., Gaeta, A. L. & Lipson, M. New CMOS-compatible platforms based on silicon nitride and Hydex for nonlinear optics. Nature Photonics 7, 597–607, doi:10.1038/Nphoton.2013.183 (2013).

Mizrahi, V., Saifi, M. A., Andrejco, M. J., DeLong, K. W. & Stegeman, G. I. Two-photon absorption as a limitation to all-optical switching. Optics Letters 14, 1140–1142, doi:10.1364/ol.14.001140 (1989).

Zhang, H. et al. Z-scan measurement of the nonlinear refractive index of graphene. Optics Letters 37, 1856–1858 (2012).

Bao, Q. L. et al. Atomic-Layer Graphene as a Saturable Absorber for Ultrafast Pulsed Lasers. Adv Funct Mater 19, 3077–3083, doi:10.1002/adfm.200901007 (2009).

Zhang, H., Bao, Q. L., Tang, D. Y., Zhao, L. M. & Loh, K. Large energy soliton erbium-doped fiber laser with a graphene-polymer composite mode locker. Appl Phys Lett 95, doi:10.1063/1.3244206 (2009).

Lu, S. B. et al. Broadband nonlinear optical response in multi-layer black phosphorus: an emerging infrared and mid-infrared optical material. Opt Express 23, 11183–11194, doi:10.1364/Oe.23.011183 (2015).

Lu, S. B. et al. Ultrafast nonlinear absorption and nonlinear refraction in few-layer oxidized black phosphorus. Photonics Res 4, 286–292, doi:10.1364/Prj.4.000286 (2016).

Lu, S. B. et al. Third order nonlinear optical property of Bi2Se3. Opt Express 21, 2072–2082, doi:10.1364/Oe.21.002072 (2013).

Zhu, Y. W. et al. Graphene and Graphene Oxide: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Advanced Materials 22, 3906–3924 (2010).

Loh, K. P., Bao, Q. L., Eda, G. & Chhowalla, M. Graphene oxide as a chemically tunable platform for optical applications. Nature Chemistry 2, 1015–1024 (2010).

Jiang, X. F., Polavarapu, L., Neo, S. T., Venkatesan, T. & Xu, Q. H. Graphene Oxides as Tunable Broadband Nonlinear Optical Materials for Femtosecond Laser Pulses. Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 3, 785–790 (2012).

Zhang, X. L. et al. Transient thermal effect, nonlinear refraction and nonlinear absorption properties of graphene oxide sheets in dispersion. Opt Express 21, 7511–7520 (2013).

Liu, Z. B. et al. Ultrafast Dynamics and Nonlinear Optical Responses from sp(2)- and sp(3)-Hybridized Domains in Graphene Oxide. Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2, 1972–1977 (2011).

Zheng, X., Jia, B., Chen, X. & Gu, M. In Situ Third-Order Non-linear Responses During Laser Reduction of Graphene Oxide Thin Films Towards On-Chip Non-linear Photonic Devices. Advanced Materials 26, 2699–2703, doi:10.1002/adma.201304681 (2014).

Ren, J. et al. Giant third-order nonlinearity from low-loss electrochemical graphene oxide film with a high power stability. Appl Phys Lett 109, 221105, doi:http://dx.doi.org/, doi:10.1063/1.4969068 (2016).

Hummers, W. S. & Offeman, R. E. Preparation of Graphitic Oxide. Journal of the American Chemical Society 80, 1339 (1958).

Li, D., Muller, M. B., Gilje, S., Kaner, R. B. & Wallace, G. G. Processable aqueous dispersions of graphene nanosheets. Nature Nanotechnology 3, 101–105 (2008).

Yan, H. & Wei, J. S. False nonlinear effect in z-scan measurement based on semiconductor laser devices: theory and experiments. Photonics Res 2, 51–58 (2014).

Sheikbahae, M., Said, A. A., Wei, T. H., Hagan, D. J. & Vanstryland, E. W. Sensitive Measurement of Optical Nonlinearities Using a Single Beam. Ieee Journal of Quantum Electronics 26, 760–769 (1990).

Eda, G. et al. Blue Photoluminescence from Chemically Derived Graphene Oxide. Advanced Materials 22, 505 (2010).

Liu, Z. B. et al. Nonlinear optical properties of graphene oxide in nanosecond and picosecond regimes. Appl Phys Lett 94 (2009).

Zheng, X. The optics and applications of graphene oxide PhD thesis, Swinburne University of Technology (2016).

Grillet, C. et al. Amorphous silicon nanowires combining high nonlinearity, FOM and optical stability. Opt Express 20, 22609–22615, doi:10.1364/Oe.20.022609 (2012).

Ikeda, K., Saperstein, R. E., Alic, N. & Fainman, Y. Thermal and Kerr nonlinear properties of plasma-deposited silicon nitride/silicon dioxide waveguides. Opt Express 16, 12987–12994, doi:10.1364/Oe.16.012987 (2008).

Yan, X. Q., Liu, Z. B., Zhang, X. L., Zhou, W. Y. & Tian, J. G. Polarization dependence of Z-scan measurement: theory and experiment. Opt Express 17, 6397–6406 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support of Department of Energy (grant DE-SC0013178). B.J. acknowledges the support from the Australian Research Council through the Discovery Early Career Researcher Award scheme (DE120100291) and the Defense Science Institute Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.X. and R.T.C. designed and supervised the research. X.Z. and B.J. prepared the samples. X.X., F.H., and Z.W. conducted the measurement. X.X., X.Z., Y.W. and B.J. analyzed the data. All the authors contribute to the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, X., Zheng, X., He, F. et al. Observation of Third-order Nonlinearities in Graphene Oxide Film at Telecommunication Wavelengths. Sci Rep 7, 9646 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09583-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09583-6

This article is cited by

-

Graphene oxide for photonics, electronics and optoelectronics

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2023)

-

High-speed all-optical 2-bit multiplier based on photonic crystal structure

Photonic Network Communications (2022)

-

High strength, flexible, and conductive graphene/polypropylene fiber paper fabricated via papermaking process

Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials (2022)

-

Design and simulation of a compact all-optical 2-to-1 digital multiplexer based on photonic crystal resonant cavity

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2022)

-

An ultra-fast all-optical 2-to-1 digital multiplexer based on photonic crystal ring resonators

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.