Abstract

A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective randomized studies were performed to evaluate the diagnostic value of measuring global longitudinal strain (GLS) using speckle tracking echocardiography (STE) in determining myocardial infarction (MI) size, which is usually measured based on late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) by cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR). Eleven trials with a total of 765 patients were included. The pooled correlation was 0.70 (95% CI: 0.64, 0.74) between two-dimensional (2D) GLS and the LGE percentage, and it was 0.55 (95% CI: 0.19, 0.78) for three-dimensional (3D) GLS. Pooled diagnostic estimates for 2D GLS to differentiate an MI size >12% were as follows: sensitivity, 0.77 (95% CI: 0.61, 0.90); specificity, 0.86 (95% CI: 0.68, 0.96); positive likelihood ratio (PLR), 8.13 (95% CI: 1.90, 26.61); negative likelihood ratio (NLR), 0.28 (95% CI: 0.10, 0.54); and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), 39.87 (95% CI: 4.12, 172.83). The estimated area under the curve (AUC) of the summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve was 0.702. The 2D STE results positively correlated with the infarction size quantified by CMR for patients who had experienced their first MI. This approach can serve as a good diagnostic index for assessing infarction area. However, more consolidated STE studies are still needed to determine the value of 3D STE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI), and especially acute MI (AMI), is a major life-threatening cardiovascular event that places huge disease and economic burdens on society1. Assessment of the size and distribution of the infarction area after revascularization therapy can facilitate prompt and appropriate clinical intervention. Biomarkers such as troponin and creatine kinase are mainly used for AMI identification but lack myocardial specificity and may overestimate the infarction size (IS)2. Conventional bedside echocardiography provides a quick and general overview of the state of the myocardium, but common indexes such as the left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) fail to detect minimal and early pathological changes3. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) provides quantitative details for myocardial fibrosis and serves as a promising tool for infarction area evaluation4, 5. However, widespread application of CMR remains limited due to its limited availability in poor areas, long scanning time and special requirements for breath-holding during an examination6.

Myocardial strain is a quantitative index based on measuring myocardial deformation during a cardiac cycle7. Major tools for detecting changes in myocardial strain include CMR tagging, CMR feature tracking (FT-CMR)6 and speckle tracking echocardiography (STE)8. Previous studies have shown an advantage of strain in sensitively and accurately diagnosing and assessing IS compared to traditional functional indexes9. However, the degree to which strain analysis can reflect the infarction areas quantified by CMR as well as the diagnostic accuracy of this analysis is still under dispute. In the past 3 years in particular, newly developed three-dimensional (3D) STE has overcome the inherent shortcomings of two-dimensional (2D) STE but has shown uneven diagnostic performance in different studies. Until now, no systematic reviews or meta-analyses have been conducted to clarify and address these issues. Thus, we conducted a meta-analysis and systematic review of the studies evaluating the performance of STE in detecting and assessing infarctions after AMI.

Results

Search strategy and study selection

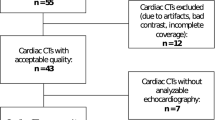

The online search initially yielded 1210 literature citations. Of those citations, 1138 were excluded after reviewing the titles and keywords because of non-relevance or repetition. Two authors (M.M. and K.D.) reviewed 72 abstracts and selected 16 studies for full-text evaluation. Simultaneously, another author (X.L.) reviewed the citations in the 16 studies and added 4 more papers for full-text evaluation. Further reading excluded papers according to the previously defined criteria. Seven studies were excluded due to not using the required index for interpreting STE and LGE results, and 2 studies were excluded for a lack of data needed for the meta-analysis. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart depicting the process for the systematic literature search and study selection is shown in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

Ultimately, 11 prospective studies published between 2007 and 2016 were chosen for systematic review. Among these studies, 10 quantitatively estimated the correlation between the strain results analysed by echocardiography and the scar size measured on CMR10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19, and 8 reported the overall diagnostic value of STE in determining IS20. All the studies used 1.5 T MRI and performed LGE following reference standards (0.1 to 0.2 mmol/kg gadolinium; 10 to 20 min for imaging) for IS quantification (Table 1).

In total, 765 patients (with a mean age of 58.8 years) were included; more detailed baseline characteristics are presented in Table 2. LVEF, hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM) and current smoking status were the most concerning and commonly recorded items.

The quality assessment showed an acceptable overall risk of bias and applicability concerns. All studies provided detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria, except for the study by M.F.A. et al. Three studies failed to use credible time intervals between echocardiography and CMR tests. Only three studies confirmed that both the echocardiography and the CMR tests were conducted in a blinded manner. Further details are provided in Fig. 2.

Correlation between STE and scar size

CIs were computed for all of the selected 11 studies (Table 3). Among these studies, 7 reported 2D STE results, whereas 4 studies reported 3D STE results. GLS was the only shared reported item and was the most correlated item according to the results of the selected studies. The pooled r-value for the 7 studies for reporting correlations between 2D GLS assessed by echocardiography and the LGE area measured on CMR was 0.70 (95% CI: 0.64, 0.74), without notable heterogeneity (chi-squared = 4.45, P = 0.62 for the Q test and I^2 = 1.44%) (Fig. 3a). However, the r-value for the 4 studies that applied 3D STE was 0.55 (95% CI: 0.19, 0.78), and there was notable heterogeneity (chi-squared = 17.38, P = 0.0006 for the Q test and I^2 = 85.99%) (Fig. 3b). Leave-one-out diagnostics were performed to test the source of heterogeneity, and a study by Wenhui Z et al. showed a significant influence, excluding a pooled r-value of 0.38 (95% CI: 0.22, 0.54) that could be reached without heterogeneity (chi-squared = 0.9425, P = 0.6242 for the Q test and I^2 = 0.00%).

A funnel plot was performed to test for publication bias, and no prominent bias was found. Considering that the number of selected studies was less than 10 and that no reliable test is available at this level, the trim-and-fill method was performed to test the results after considering possible publication bias. The corrected r-values for 2D GLS and 3D GLS were 0.88 (95% CI: 0.80, 0.98) and 0.61 (95% CI: 0.19, 1.04), respectively.

Diagnostic accuracy of STE

The data extracted from the selected studies are shown in Table 4.

For differentiating maximal (>12%) and minimal (<12%) ISs, the selected studies showed sensitivities ranging from 0.68 to 0.85. The specificities ranged from 0.83 to 0.96, and the area under the curve (AUC) values ranged from 0.80 to 0.95. Pooled estimates were as follows: sensitivity, 0.77 (95% CI: 0.61, 0.90); specificity, 0.86 (95% CI: 0.68, 0.96); positive likelihood ratio (PLR), 8.13 (95% CI: 1.90, 26.61); negative likelihood ratio (NLR), 0.28 (95% CI: 0.10, 0.54); and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), 39.87 (95% CI: 4.12, 172.83). The summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve summarized the overall diagnostic accuracy, showing a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity in which the calculated AUC was 0.702 (Fig. 4a).

For assessing the transmurality of the infarction area, the selected studies showed sensitivities ranging from 0.72 to 0.80 and specificities ranging from 0.72 to 0.85, and the AUC values ranged from 0.66 to 0.88. The pooled estimates for 2D GLS were as follows: sensitivity, 0.76 (95% CI: 0.66, 0.84); specificity, 0.79 (95% CI: 0.69, 0.87); PLR, 3.79 (95% CI: 2.19, 6.52); NLR, 0.31 (95% CI: 0.19, 0.47); and DOR, 13.46 (95% CI: 4.94, 30.37). The corresponding SROC curves are shown in Fig. 4b, and the estimated AUC was 0.652.

Discussion

MI size has long played a major role in clinical decision-making. In this context, accurate and quick morphological and functional evaluations are profoundly significant. Our study, which included a meta-analysis and systematic review, is the first to summarize the previous research on the diagnostic value of GLS determined by performing 2D and 3D STE in MI patients.

First, our results showed good overall correlation between the 2D GLS and the LGE results, which are superior to conventional indexes, including both troponin level21, 22 and LVEF23. Second, for using GLS results to differentiate large and small infarctions or to predict transmural MI, the pooled diagnostic value was inferior to the results for each individual centre. The pooled DOR, PLR and NLR results showed a better diagnostic performance for differentiating a 12% MI size than for differentiating a 50% MI size. The DOR results showed that GLS had a moderately accurate diagnostic value for differentiating ISs >12% and <12%. For differentiating transmural infarctions, however, although the DOR was >1, the results still indicated a relatively poor performance. The cut-off values for GLS are still variable and might depend on the experience of clinicians at different centres. Additionally, previous studies on both GLS and other diagnostic indexes did not show better results for diagnostic methods other than GLS11. Additionally, in assessing the viability of the myocardium after MI, LVEF might have better performance17.

Classical myocardial theory was used to demonstrate a three-layer model, including inner and outer oblique fibres and a more horizontal middle layer. The pumping function of the heart has been attributed to the contractions of fibres in different orientations. Pathological changes in MI usually start from the endocardium and develop to the outmost layer with prolongation of the ischaemia time. According to a previous study7, the change in longitudinal strain is most prominent during the pre-ejection and ejection phases. Therefore, even the circumferential strain (CS) of the myocardium at the endocardial layer is twice that of the myocardium at the epicardial layer24, and most studies still show better sensitivity to dysfunctional change for GLS than for global CS. A reason might be that the ultrasound beam of the probe is longitudinal and thus parallel to the GLS, which helps to achieve better resolution in the longitudinal direction, whereas GCS is calculated from the short axis and is thus inevitably affected by low resolution in the basal and apex layers. Advancement in algorithms and methodologies might improve the accuracy of GCS in the future.

According to our results, 2D GLS has better performance than 3D GLS as well as when compared to results generated by CMR. Interestingly, for the studies using both 2D and 3D STE, better performance was seen for 3D GCS calculations than for 2D GCS16, 19. The two technologies have two primary differences that might explain this result. First, compared to 2D STE, real-time 3D STE overcomes the cross-lane tracking shortcoming of 2D STE to allow for a quick overall evaluation of the heart. However, this feature is limited by the sole capacity for a full-wall thickness assessment, in contrast to the multi-layered assessment provided by 2D STE. Second, strain change in the longitudinal direction can be mainly attributed to the oblique layers of sub-endocardium and can lead to a preference for single-layer analysis, although transverse strain varies in all the layers of myocardium, which might be more suited to more thorough data collection throughout the myocardium. Thus, 3D STE might be more suitable than 2D STE for GCS evaluation and may not be accurate enough for GLS evaluation. However, 3D STE is still a promising developing new technology, and the heterogeneity among previous 3D STE studies demonstrates that more studies are still needed to clarify the differences between 2D and 3D STE as well as the technical advancements in image analysis for 3D STE.

Other than 3D STE, another promising strain analysis tool is FT-CMR. Compared to the traditional CMR tagging technique, FT-CMR borrows the 2D deformation analysis algorithm from 2D STE and adapts it to a CMR cine steady-state free precession (SSFP) sequence, which is exempt from additional scans or contrast injection. However, FT-CMR tracks deformation more on the endocardial border, whereas STE is concentrated on intra-myocardial changes. A previous review also reported that the strain analysed by FT-CMR was lower than that analysed by STE25. Additionally, software for FT-CMR is relatively rare, leading to highly identical parameters recorded among studies, whereas the software and assessment standards for STE are highly variable26. Thus, arbitrarily deciding which technique is better is not appropriate, and more studies are still needed. Furthermore, the development of a new strain calculation was also noted during the present review.

Limitations

For this meta-analysis, there are two main limitations. First, a relatively small group of studies was included for assessment of diagnostic accuracy. Due to the different thresholds used in different studies, we failed to achieve a pooled result based on more studies. Second, heterogeneity was observed for 3D STE studies. As discussed above, the standard for applying STE analysis is deficient, and its revision is a goal of the new European Society of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography strain standardization task force. More studies with a relatively standard procedure are needed to achieve more credible results.

In conclusion, GLS measured by 2D STE had a good correlation with the IS quantified by CMR for patients with first-time MI and can serve as a clinical diagnostic factor for assessing the MI area. Meanwhile, the 3D STE approach showed inferior diagnostic value compared to 2D STE, and more consolidated 3D STE studies are still needed to clarify the value of this technology.

Methods

Following PRISMA standards27, our main process of review and assessment was conducted as described below.

Search strategy

Two independent reviewers (L.X. and M.M.) separately searched PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register for studies using the following keywords: “myocardial ischemia” OR “coronary artery disease” OR “myocardial infarction” AND “speckle tracking echocardiography” OR “two-dimensional echocardiography” OR “three-dimensional echocardiography” AND “strain” AND “size” OR “area” OR “viable myocardium” AND “evaluation” OR “assessment” OR “diagnosis”. We confined the publication date range to 2005 until present. We also verified and manually searched for certain papers in the reference lists of the selected studies. We put no limits on language.

Study selection

Studies were included if they 1) randomly and prospectively enrolled patients with one MI, 2) performed standard methods to acquire LGE as the reference for infarction area quantification, 3) performed either 2D or 3D STE or both and recorded GLS for myocardial function assessment, and 4) performed credible statistical methods to study the correlation between STE and CMR or to evaluate the diagnostic value of GLS determined by STE or both.

Two main types of studies were considered in the literature search. The first type performed a scar size assessment in which the correlations between the results from echocardiography and CMR were studied. The other type reported the diagnostic value of echocardiography in differentiating large and small MIs or recognizing transmural MI.

To define the borderline size of the scar tissue, the percentage of the LGE area in the left ventricle was taken as the standard interpretation. A value of 50% was mainly used to define transmural MI, considering that previous studies noted this value as the cut-off for differentiating myocardial recovery ability after revascularization4. In addition to that value, 12% was the preferred threshold for differentiating maximal and minimal MIs because it has been shown to have a notable correlation with mortality28.

Quality assessment

Patient selection, the index and reference tests, and flow and timing were mainly considered to assess study quality while referring to the items in the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2)29.

Data extraction

Two other reviewers (Q.Z. and Y.G.) carefully reviewed the full text and extracted the intended data from the selected studies. Any discrepancies between the two were referred to another reviewer (K.D.) for a final decision. We recorded the patients’ basic information, the target correlation factor and the 2 × 2 data for reporting diagnostic accuracy as well as the different borderline LGE results or STE cut-off values used. Furthermore, we recorded the methodological techniques mentioned by the authors in each study and summarized these techniques in our results.

For studies that did not provide 2 × 2 data, we used the summary results to calculate the responding true-positive, true-negative, false-positive and false-negative values.

Data analysis

The baseline variables for the patients are given as the proportion (percentage), and continuous variables are given as the mean (SD) or median (range). The time intervals for the different measurement methods were calculated and are reported in the format of time ranges.

For studies reporting correlation factors between the scar sizes measured by STE and LGE, we calculated the CI for each correlation coefficient and the pooled r-value using a method described in a previous study30.

For studies reporting the diagnostic accuracy of STE, we computed the pooled sensitivity, specificity, PLR, NLR, and DOR and generated a forest plot accordingly. The DOR was considered the major diagnostic accuracy assessment index independent of disease prevalence, with a DOR > 25 considered to be moderately accurate and a DOR > 100 considered to be highly accurate31. An SROC curve was calculated with the sensitivity and specificity values provided by every single study.

Statistical heterogeneity was calculated as I^2, and if the heterogeneity was significant, the results of the random-effect model were reported. We also performed a sensitivity test to see if excluding any study provided lower heterogeneity. A funnel plot was used to measure publication bias, and Egger’s32 test was used as well if the tested groups included more than 10 studies. The trim-and-fill method was used if prominent bias was observed. The meta-analyses were performed using R Project (3.3.1) with the freeware package (meta4diag and metafor, 2016).

References

Gabriel, P. et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. European Heart Journal. 1–51 (2012).

Hundley, W. G. et al. Expert consensus document ACCF/ACR/AHA/NASCI/SCMR 2010 Expert Consensus Document on Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. JACC 55(23), 2614–2662 (2010).

Kalam, K., Otahal, P. & Marwick, T. H. Prognostic implications of global LV dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global longitudinal strain and ejection fraction. Heart 100, 1673–1680 (2014).

Kim, R. J., Wu, E. & Rafael, A. et al. Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Identify Reversible Myocardial Dysfunction. N Engl J Med 343, 445–1453 (2000).

Kancharla, K. et al. Scar quantification by cardiovascular magnetic resonance as an independent predictor of long-term survival in patients with ischemic heart failure treated by coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 18(45), 1–9 (2016).

Piechnik, S. K. et al. Shortened Modified Look-Locker Inversion recovery (ShMOLLI) for clinical myocardial T1-mapping at 1.5 and 3 T within a 9 heartbeat breathhold. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 12(69), 1–11 (2010).

Buckberg, G., Hoffman, J. I. E., Mahajan, A., Saleh, S. & Coghlan, C. The Relationship of Cardiac Architecture to Ventricular Function. Circulation 118, 2581–2587 (2008).

British, H., Society, C. & Rodrigues, J. C. L. Intra-ventricular myocardial deformation strain analysis in healthy volunteers: regional variation and implications for regional myocardial disease process. Heart 102, 16 (2016).

Schuster, A., HK, N., Beerbaum, T. K. J. & Kutty, P. S. Advances in Cardiovascular Imaging Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Myocardial Feature Tracking Concepts and Clinical Applications. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 9(1–10), e004077 (2016).

Vartdal, T. et al. Early Prediction of Infarct Size by Strain Doppler Echocardiography After Coronary Reperfusion. J Am Coll Cardio 49, 1715–1721 (2007).

Eek, C., Grenne, B., Brunvand, H. & Aakhus, S. Strain Echocardiography and Wall Motion Score Index Predicts Final Infarct Size in Patients with Non – ST-Segment – Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 3, 187–194 (2010).

Mistry, N. et al. Assessment of left ventricular function in ST-elevation myocardial infarction by global longitudinal strain: a comparison with ejection fraction, infarct size and wall motion score index measured by non-invasive imaging modalities. Eur J Echocardiogr 12, 678–683 (2011).

Hayat, D., Kloeckner, M. & Nahum, J. Comparison of Real-Time Three-Dimensional Speckle Tracking to Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease. AJC 109, 180–186 (2012).

Grabka, M. et al. Prediction of infarct size by speckle tracking echocardiography in patients with anterior myocardial infarction. Coronary artery Dis 24, 127–134 (2014).

Thorstensen, A., Hala, P., Kiss, G., Sc, M. Three-Dimensional Echocardiography in the Evaluation of Global and Regional Function in Patients with Recent Myocardial Infarction: A Comparison with Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Echocardiology, 682–692 (2013).

Zhu, W., Liu, W., Tong, Y. & Xiao, J. Three-Dimensional Speckle Tracking Echocardiography for the Evaluation of the Infarct Size and Segmental Transmural Involvement in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Echocardiology 31, 58–66 (2014).

Donal, E. & Terrien, G. Longitudinal Strain Is a Marker of Microvascular Obstruction and Infarct Size in Patients with Acute ST- Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. PLoS One 9, 1–9 (2014).

Loutfi, M., Ashour, S., El-sharkawy, E., El-fawal, S. & El-touny, K. Identification of High-Risk Patients with Non-ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction using Strain Doppler Echocardiography: Correlation with Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Clin Med insights Cardiol 10, 51–59 (2016).

Aly MFA, Robbers SAKRFMLF, Kamp AMBO. Three-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance for left ventricular chamber quantification and identification of myocardial transmural scar. NethHear J 24, 600–608 (2016).

Cimino, S. et al. Global and regional longitudinal strain assessed by two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography identifies early myocardial dysfunction and transmural extent of myocardial scar in patients with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction and relatively. Eur Heart J 14, 805–811 (2013).

Barth, J. H. et al. Troponin-I concentration 72 h after myocardial infarction correlates with infarct size and presence of microvascular obstruction. Heart, 1547–1551 (2008).

Steuer, S. et al. Early Diagnosis of Myocardial Infarction with Sensitive Cardiac Troponin Assays. N Engl J Med 361, 858–867 (2009).

Sibley, C. T. et al. T1 Mapping in Cardiomyopathy at Cardiac MR: Comparison with Endomyocardial Biopsy. Radiology 265, 724–732 (2012).

Oshinski, J. N. et al. Imaging Time After Gd-DTPA Injection Is Critical in Using Delayed Enhancement to Determine Infarct Size Accurately. Circulation 104, 2838–2842 (2001).

Values, N. & Applications, C. Tissue Tracking Technology for Assessing Cardiac Mechanics. JACCCardiovasc Imaging 8, 1444–60 (2015).

Voigt, J. et al. Definitions for a common standard for 2D speckle tracking echocardiography: consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to standardize deformation imaging. Eur Hear J-Cardiovasc Imaging 16, 1–11 (2015).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G. & Group, T. P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. plosmedi 6, 1–6 (2009).

Burns, R. J. et al. The Relationships of Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction, End-Systolic Volume Index and Infarct Size to Six-Month Mortality After Hospital Discharge Following Myocardial Infarction Treated by Thrombolysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 39, 30–36 (2002).

Whiting, Penny, F., Rutjes Anne, W. S. & Westwood Marie, E. et al. Research and Reporting Methods Accuracy Studies. Ann Intern Med 155, 529–538 (2011).

Diao, K. Y. et al. Histologic validation of myocardial fibrosis measured by T1 mapping: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 1–11 (2016).

Deeks, J. J. Systematic reviews of evaluations of diagnostic and screening tests. BMJ 323, 157–162 (2001).

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634 (1997).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81471722, 81471721), Application foundation project of science and technology department of Sichuan province (NO 2017JY0026),Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (No: NCET-13-0386).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.-Y.D. is responsible for work arrangement and manuscript writing; M.M. works on paper search and helps with manuscript; Y.H. is responsible for data check and study design; Y.G. and Q.Z. mainly work on data extraction; X.L. and L.J.X. help with paper search and selection; Y.-K.G. and Z.-G.Y. are both the study guarantors, had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility of the study design and the accuracy of the data analysis, and had the final responsibility to submit for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Diao, Ky., Yang, Zg., Ma, M. et al. The Diagnostic Value of Global Longitudinal Strain (GLS) on Myocardial Infarction Size by Echocardiography: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sci Rep 7, 10082 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09096-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09096-2

This article is cited by

-

Myocardial structural and functional changes in patients with liver cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation: a comprehensive cardiovascular magnetic resonance and echocardiographic study

Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (2020)

-

Evolution of left ventricular function among subjects with ST-elevation myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2020)

-

Assessment of left ventricular deformation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus by cardiac magnetic resonance tissue tracking

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

The predictive value of global longitudinal strain on late infarct size in patients with anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with a primary percutaneous coronary intervention

The International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.