Abstract

Inheritance of the apolipoprotein E4 (apoE4) genotype has been identified as the major genetic risk factor for late onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Studies have shown that apoE, apoE4 in particular, binds to amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides at residues 12-28 of Aβ and this binding modulates Aβ accumulation and disease progression. We have previously shown in several AD transgenic mice lines that blocking the apoE/Aβ interaction with Aβ12-28 P reduced Aβ and tau-related pathology, leading to cognitive improvements in treated AD mice. Recently, we have designed a small peptoid library derived from the Aβ12-28 P sequence to screen for new apoE/Aβ binding inhibitors with higher efficacy and safety. Peptoids are better drug candidates than peptides due to their inherently more favorable pharmacokinetic properties. One of the lead peptoid compounds, CPO_Aβ17–21 P, diminished the apoE/Aβ interaction and attenuated the apoE4 pro-fibrillogenic effects on Aβ aggregation in vitro as well as apoE4 potentiation of Aβ cytotoxicity. CPO_Aβ17–21 P reduced Aβ-related pathology coupled with cognitive improvements in an AD APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model. Our study suggests the non-toxic, non-fibrillogenic peptoid CPO_Aβ17–21 P has significant promise as a new AD therapeutic agent which targets the Aβ related apoE pathway, with improved efficacy and pharmacokinetic properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The pathological accumulation of Aβ peptides as toxic oligomers, amyloid plaques and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), either from increased production of Aβ peptides or from their inadequate clearance, is critical in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)1, 2. The apolipoprotein E4 (apoE4) allele, a major genetic risk factor for late-onset AD, has been strongly associated with increased amyloid plaques deposition in brain parenchyma and advanced vascular amyloid pathology such as CAA3,4,5. Numerous studies have shown that apoE binds to residues 12–28 of Aβ and this binding modulates Aβ accumulation hence affecting disease progression3, 4, 6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. However, there is no consensus on how different apoE genotypes contribute to the pathogenesis of AD3, 6, 7. It has been hypothesized that apoE and apoE4 in particular is an amyloid catalyst or “pathological chaperone”3, 8 and that the interaction of Aβ and apoE4 is associated with neurotoxicity14. Alternatively it has been posited that apoE is an Aβ clearance factor, with apoE4 being impaired at this function compared to apoE3 or E26, 15. We suggest that the optimal therapeutic strategy may be to specifically prevent the interaction of apoE with Aβ, allowing to circumvent complications of altering apoE levels which may cause detrimental effects on the many other beneficial roles apoE plays in neurobiology3, 7.

We and others have previously shown that blocking the apoE/Aβ interaction by Aβ12-28 P peptides could constitute a novel treatment for AD by reducing brain parenchymal and vascular amyloid burden as well as tau related pathology in several AD transgenic mice lines16,17,18,19,20. Recently, using peptidomimetic technology and the macrocyclization method, we designed a peptoid library derived from Aβ12-28 P sequence to screen for new apoE/Aβ binding inhibitors with higher efficacy and safety for blocking the apoE/Aβ interaction21,22,23.

Peptoids are N-substituted glycine oligomers, which recapitulate many desirable attributes of natural peptides including formation of stable secondary structures and demonstration of a range of biological activities24, 25. Advantages of peptoids over peptides include stability of their structure to excessive temperature (over 75 °C), salt, pH, and organic solvent. They are resistant to proteolytic degradation and can be excreted whole in urine, which is an important attribute of a pharmacologically useful peptide mimic24, 25. Furthermore, peptoids lack the hydrogen of secondary amides, and thus are unlikely to form the β-sheet structure, which is associated with the toxicity of Aβ and Aβ derived peptides. Peptoids can be easily synthesized by solid phase submonomer synthesis using hundreds of available primary amines and modified by various chemical ligation methods to enhance the desired biological function and/or properties. A number of peptoid based compounds have been successfully developed and introduced to clinical practice24, 25. The design of biologically-active peptoid sequences of some of these compounds was achieved by the systematic modification of an active peptide target sequence, which is the same strategy we are using to design our peptoid library for screening.

In this study, we report the synthesis of a library of peptoids based on the Aβ12-28 P sequence. We screened this library for the ability of the peptoids to diminish apoE/Aβ binding. In our report we tested the ability of CPO_Aβ17-21 P, one of the lead peptoids obtained from the inhibition potency screening, to diminish the apoE/Aβ binding in vitro monitored by surface plasmon resonance (SPR). We also tested its ability to inhibit the promoting effects of recombinant apoE4 on Aβ40 and Aβ42 aggregation using a Thioflavin T assay. We have tested the potential toxicity of CPO_Aβ17-21 P using mouse N2a and human SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cell lines. We also assayed if CPO_Aβ17-21 P could inhibit the potentiation of apoE4 on the cytotoxicity of Aβ42 using a human SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cell line. Furthermore, we found that in vivo administration of CPO Aβ17-21 P in an APP/PS1transgenic mouse AD model could reduce pathology and produce cognitive benefits.

Materials and Methods

Materials and regents

Unless stated otherwise all chemicals and regents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The Aβ12-28 P, Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides were synthesized and purified at ERI Amyloid Laboratory LLC (Oxford, CT) as previously described19. For SPR binding assay, aggregation studies and oligomeric Aβ42 cytotoxicity assessment, the Aβ peptides were treated with 1, 1, 1, 3, 3, 3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) to remove secondary structure and render peptides into monomeric forms26. The CPO_Aβ17-21 P and other peptoid compounds were designed and synthesized in the laboratory of Prof. Yong-Uk Kwon at Ewha Womans University (Korea). Recombinant human apoE4 was purchased from BioVision (Milpitas, CA) and reconstituted in ddH2O to a concentration of 1 mg/ml. Human lipidated apoE3 and apoE4 were prepared as previously published15. All cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and kept in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units penicillin and 100 µg streptomycin/mL. All cell culture regents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

Library design and synthesis of peptoids

Our library design is a systematic intelligent design approach. A series of linear and cyclic peptoids derived from Aβ12-28 were designed and synthesized on solid-phase. The sequential steps in peptoid compound synthesis involved: 1) abbreviation of Aβ12-28 sequence to the core sequence Aβ15-24 capable of blocking the apoE/Aβ interaction; 2) substitution of amino acids in shortened peptides for non-natural “peptoid” residues; 3) construction of cyclic peptoids using macrolactamization. This is a modification which is known to increase the stability of peptoids, improve cell/blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability and typically increase the affinity of binding21, 22, 25. Peptoid synthesis was done using methods as previously described23, 27. Briefly, peptoids were easily prepared on solid-phase by the submonomer strategy employing bromoacetic acid and primary amines. The polar side chain-containing amines were readily introduced under the modified synthetic conditions. For the construction of cyclic peptoids, the macrolactamization between the carboxylic acid functionality of β-alanine unit and the amino functionality of the terminal peptoid unit was successfully carried out in the presence of the coupling agent PyAOP23, 27.

SPR monitoring

Experiments were performed using a Reichert SR7000DC refractometer system (Reichert, New York) equipped with a CM5 sensor chip. Acetate buffer was used for immobilization of the peptide Aβ42 (ligand). We used Aβ42 for these binding studies (and not Aβ40), since Aβ42 species are the major constituents of amyloid plaques, with Aβ40 species being more common in vascular amyloid28, 29; although some reports suggest that Aβ40 species overall can be the most abundant in the AD cortex30, 31. Importantly, Aβ42 species are considered critical for seeding of amyloid deposits2, 32. CM-dextran on a CM5 gold sensor chip was activated by injecting a solution of 10 mg/mL N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and 40 mg/mL 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) over the sensor chip surface for 7 min at a flow rate of 20 µL/min. Then the ligand, 50 µg/mL HFIP treated synthetic peptide Aβ42 in 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5, was immobilized by injection over the surface for 20 min. The unreacted sites on the sensor chip surface were blocked by injection of 1 M ethanolamine, pH 8.5 for 10 min. Analytes containing recombinant human apoE4 molecules pre-incubated with various peptoid inhibitors at different concentrations in phosphate buffered saline with 0.05% TWEEN 20, pH 7.4 (PBST) were injected over the surface and the association and dissociation reactions were monitored. After each binding cycle the surface was regenerated by a short, fast injection of 10 mM hydrochloric acid. To verify results analytes containing lipidated human apoE4 molecules or lipidated human apoE3 molecules incubated with peptoid inhibitors in phosphate buffered saline with 0.05% TWEEN 20, pH 7.4 (PBST) were tested and the association and dissociation reactions were monitored.

Aggregation assay

Peptide Aβ42 or peptoid CPO_Aβ17-21 P were incubated alone at a concentration of 100 µM over a period of 7–10 days at 37 °C in 100 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4). Aβ42 was also incubated in the presence of 1 µM of recombinant human apoE4 or CPO_Aβ17–21 P (100:1 molar ratio), under the same conditions. In aggregation inhibition experiments, apoE4 was pre-incubated with CPO_Aβ17-21 P in a molar ratio of 1:2 for 6 hrs at 37 °C followed by addition to freshly reconstituted Aβ42 on ice (molar ratio 100:1:2, Aβ42:apoE4:peptoid). As a control, Aβ42 was also incubated with CPO_Aβ17-21 P at a molar ratio of 100:2. For peptide Aβ40 all the experiments were conducted under the same conditions as Aβ42 except the peptide concentration was 400 µM. The molar ratio of Aβ40:apoE4:CPO_Aβ17-21 P was 100:1:2. (400 µM Aβ40:4 µM apoE4:8 µM CPO_Aβ17-21 P). Fibril formation by the different peptides at various time points was evaluated by a standard Thioflavin-T assay according to previously published protocols13, 33.The samples were diluted in buffer containing 50 mM glycine, 2 µM Thioflavin T pH 9.2, and read on a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M2 spectrophotometer (Sunnyvale, CA) at excitation and emission wavelengths 440 and 482 nm.

Cell viability assay

The effects of 0.1 to 10 µM concentrations of CPO_Aβ17-21 P on the viability of SK-N-SH human or N2a mouse neuroblastoma cell line were assessed initially for peptoid compound cytotoxicity in cell cultures. Cells from the fifth passage and beyond were seeded in fifty-eight of the central sixty wells of a Greiner 96 well cell culture plate (Baton Rouge, LA) with clear flat bottom and black wall at 5,000 cells per well leaving two of the central wells unseeded as blank control. The next day, cells were washed twice carefully with warm plain medium and different concentrations of CPO_ Aβ17-21 P diluted in plain DMEM medium containing 1% N-2 supplement and added to cells at a final volume of 100 μl per well. Every treatment group contained 5-6 replicates. 100 µL of distilled water was added to the side wells and corner wells of the plate in order to minimize evaporation during incubation. The plate was incubated at 37 °C 5% CO2 for 24 hrs followed by cell viability assay using Promega CellTiter-Blue® Cell Viability Assay kit (Madison, WI) according to the product manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 20 µL of CellTiter-Blue regent was added to each of the central 60 wells and the plates were incubated at 37 °C 5% CO2 for 1–4 hrs to allow live cells to convert a redox dye resazurin into a fluorescent end product resorufin, and the fluorescent signal was measured by a Synergy H-1 Hybrid Reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT) at 560Ex/590Em. All experiments were run in triplicate.

In toxicity rescue experiments CPO_Aβ17–21 P or Aβ12–28 P (as positive control) were used to neutralize recombinant human apoE4’s effects on oligomeric Aβ42 neurotoxicity. Oligomeric Aβ42 was prepared as previously published26. To prepare 100 µM oligomeric Aβ42 stock solution, 0.45 mg HFIP pretreated Aβ42 peptide was dissolved into 20 µl fresh dry dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to form 5 mM Aβ42 DMSO solution; then 980 µl ice cold phenol-free Ham’s F-12 cell culture medium (with 146 mg/L L-Glutamine) was added to the Aβ42 DMSO solution followed by incubation at 4 °C for 24 hrs. CPO_ Aβ17–21 P or Aβ12-28 P was pre-incubated with apoE4 in DMEM medium containing 1% N-2 supplement for 6 hrs at 37 °C then mixed with freshly prepared oligomeric Aβ42 and added to SK-N-SH cells. For comparison, cells were incubated with Aβ42 alone and Aβ42 + apoE4, apoE alone, Aβ42 + CPO_Aβ17-21 P and Aβ42 + Aβ12-28 P as additional controls. The final concentration of peptides or peptoids was as follows: Aβ42 10 µM, apoE4 1 µM, Aβ12-28 P 4 µM and CPO_Aβ17-21 P 1 µM or 4 µM. Cells were under different treatments for three days and the cell viability was assessed as described above.

Transgenic mice and treatment

The effect of CPO_Aβ17-21 P on Aβ deposition was tested in APP/PS1 Tg mice with plaque pathology34. This AD mouse model develops plaque pathology from the age of 3 months. Animals were divided into two groups and received intraperitoneally (i.p.) injections of 0.2 mg of CPO_ Aβ17–21 P per mouse in sterile saline (n = 11, 5 male, 6 female) or saline alone (n = 10, 5 male, 5 female) as a control twice weekly for 4 months, beginning at age 3 months. During the treatment, veterinary staff monitored animals for any signs of toxicity, such as changes in body weight, physical appearance, and altered behavior. Animals were sacrificed a week after administration of the last treatment dose and behavioral testing. All mouse care and experimental procedures were compliant with guidelines of animal experimentation and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the New York University School of Medicine.

Behavioral testing

Behavioral tests were performed during the last month of treatment. All testing were conducted by an individual blinded to the treatment assignment. To verify that any treatment effects observed in the cognitive tests are not due to differences in motor abilities, sensorimotor tests including locomotor activity, rotarod and traverse beam were performed to measure general motor functions, coordination and balance, as previously described35,36,37. Radial arm maze test and novel object recognition test were performed to evaluate treatment associated cognitive improvements of spatial learning (working memory) and short-term memory as previously described19, 35, 37.

Locomotor Activity

Mouse locomotor activity was recorded by a Hamilton-Kinder Smart-frame Photobeam System (Kinder Scientific, Poway, CA). Following habituation in a circular open field chamber (70 × 70 cm) for 15 min, each mouse was allowed to explore the environment for 15 min. Horizontal movements of the mice were automatically recorded and results were reported as distance traveled (cm), average and maximum travel velocity (cm/s) and mean resting time (s) of the mouse.

Rotarod

Mice were habituated to reach a baseline level of performance, before being tested for 5 min on a 3.6 cm diameter rod (Rotarod 7650 accelerating model; Ugo Basile Biological Research Apparatus, Varese, Italy) with initial speed set at 1.5 rpm then raised every 30 sec by 0.5 rpm. To access performance, the speed of the rod was recorded when the mouse fell or inverted (by clinging) from the top of the rotating barrel during three test trials. A soft cushion was placed under the rod to prevent injury from falling.

Traverse Beam

Mice were assessed by their ability to traverse a graded narrow wooden beam to reach a goal box. During the test, mice were placed on a 1.1 cm wide beam, 50.8 cm long, 30 cm above a padded surface, in a perpendicular orientation to habituate, and were then monitored for a maximum of 60 sec. The number of foot slips each mouse made before falling or reaching the goal box was recorded for each of three successive trials. The average numbers of foot slips of the mice from different treatment groups in three trials were calculated.

Radial Arm Maze

Spatial learning (working memory) was tested using a radial arm maze with eight radial 30-cm-long arms originating from the central space. A well baited with 0.2 ml of 0.1% saccharin solution was placed at the end of each arm. Mice were deprived of water for 24 hrs before testing, and then water access was restricted to 1 hr per day for the duration of testing. The task required an animal to enter all arms and drink the saccharin solution until the eight rewards had been consumed. After 3 days of adaptation, mice were subjected to testing for 9 consecutive days. The number of errors (entry into previously visited arms) was recorded during each session.

Object Recognition

The spontaneous object recognition test measures short-term memory. It was conducted in a square-shaped open-field box (48 cm square, with 18 cm-high walls constructed from black Plexiglas). Objects were placed diagonally in the center of two zones and mice were allowed to explore two identical objects in the open field for 15 min. 24 hrs later this procedure was repeated with two novel identical objects. At the end of the training phase, mice were removed from the box for the duration of the retention delay (3 hrs). During retention session, one of the previous familiar objects used during training was replaced by a second novel object and the animal was allowed to explore freely for 6 min. The amount of time spent exploring each object within a defined zone of the area was automatically recorded by a tracking system (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA).

Tissue processing and immunohistochemistry

Mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (150 mg/kg, i.p.) and blood was collected via cardiac puncture and plasma was separated by centrifugation. Animals were perfused transaortically. The brains and internal organs were collected and cut into halves, one half immersion-fixed in periodate-lysine paraformaldehyde (PLP) for histopathological analysis, and another half snap-frozen for biochemical studies as previously described19. Serial coronal brain sections (40 μm) were cut evenly spaced every 400 μm μm along the entire rostro-caudal brain axis and stained for immunohistochemical analysis with: (1) a mixture of anti-Aβ monoclonal antibodies 6E10/4G8 (1 :2000) (Covance, Princeton, NJ), (2) polyclonal anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody (1:1000) (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), (3) polyclonal anti-Iba1 antibody (1:1000) (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA) and (4) monoclonal anti-CD11b (1: 500) (Serotec, Raleigh, NC). To measure treated mice brain total amyloid burden change, two different anti-Aβ monoclonal antibodies with distinct epitopes 6E10 (epitope Aβ1–16) and 4G8 (epitope Aβ17–24) were used38. To examine brain inflammation levels associated with treatment, we assessed the degree of astrocytosis with GFAP immunoreactivity and the degree of microgliosis with Iba1 and CD11b immunoreactivity as previously published19, 37, 39, 40. GFAP is a component of the glial intermediate filaments that form part of the cytoskeleton and is found predominantly in astrocytes36. CD11b is a protein subunit that forms integrin alpha-M beta-2 (αMβ2) molecule, also known as MAC-1 or complement receptor 3 (CR3). CD11b monoclonal antibodies are commonly used for detection of microglial activation at the earliest stages of plaque development41. In addition, Iba1 (ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule) antibody was used to label the entire microglia population including activated and resting microglia, a marker for detecting generic microglia42, 43. Immunohistochemistry was performed on free floating coronal brain sections. Details of the procedure and techniques were described previously19, 37, 39, 40. Antibody staining was revealed with 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma-Aldrich) and nickel ammonium sulfate (Ni; Mallinckrodt, Paris, KY) for intensification. Human Alzheimer disease patients brain sections were used for positive control immunostaining, sequential mouse brain sections with omission of the primary antibody were used for negative immunostaining controls.

Quantification of amyloid burden, astrocytosis and microgliosis

Amyloid burden was measured by a Bioquant stereology (BIOQUANT Image Analysis Corporation, Nashville, TN) semi-automated image analysis system using a randomized and unbiased sampling scheme according to our previous published protocol17, 19, 37, 39, 40. The total amyloid burden (defined as the percentage of test area occupied by Aβ immunoreactivity) was quantified for the cortex and hippocampus on coronal plane sections stained with a mixture of anti-Aβ antibodies 6E10 (epitope Aβ1–16)/4G8 (epitope Aβ17–24). The staining resulted in black Aβ immunoreactivity due to the intensification with nickel ammonium sulfate and facilitated threshold detection. The cortical area was measured as dorsomedial from the cingulate cortex and extended ventrolaterally to the rhinal fissure within the right hemisphere. Test areas (640 µm × 480 µm) were randomly selected by a grid (800 µm × 800 µm) over the traced contour. 8 sections, approximately 80 areas, were analyzed per animal. Hippocampal measurements (grid area, 600 µm × 600 µm) were performed similar to the cortical analysis (7 sections, and approximately 85 areas per animal).

The assessment of astrocytosis and microgliosis were based on a semi-quantitative analysis, using methods we have previously published by a rater blinded to the treatment status of the mice19, 37, 39, 40. Prior to analysis, brains were microscopically examined and rated on a scale from 0–4, in increments of 0.5, depending on the degree of pathology and/or the activation stage of the glial cells. All stained cortical and hippocampal sections were analyzed at 10x magnification. Approximately 8 cortical sections and 6 hippocampal sections were analyzed per animal. Astrogliosis evaluation was based on GFAP immunoreactivity (number of GFAP immunoreactive cells and complexity of astrocytic branching) on a scale from 0 (few resting astrocytes) to 4 (numerous reactive astrocytes/extensive branching), as previously published19, 37, 39, 40. Microgliosis was assessed on CD11b and Iba1 immunostained sections with rating from 0 (few resting microglia) to 4 (numerous ramified/phagocytic microglia) in increments of 0.5.

Assessment of levels of Aβ and oligomeric Aβ in the brain by ELISA

Brains were weighed and homogenized (10% w/v) in tissue homogenization buffer (20 mM Tris base, pH 7.4, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA) with 100 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, complete protease inhibitor cocktail and PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) added immediately before homogenization. The extraction of soluble Aβ and total Aβ was according to the method we have published previously37, 44. Brain homogenates were mixed with an equal volume of cold 0.4% diethylamine (DEA)/100 mM NaCl, and subsequently centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 hr at 4 °C. The supernatant was neutralized with 1/10 volume of 0.5 M Tris, pH 6.8, flash-frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C until used for ELISA analysis as soluble Aβ fraction. For extraction of the total Aβ, homogenates (200 μl) were added to 440 μl of cold formic acid (FA) and sonicated for 1 min on ice. Subsequently, 400 μl of this solution was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C and 210 μl of the resulting supernatant was diluted into 4 ml of FA neutralization solution (1 M Tris base, 0.5 M Na2HPO4, 0.05% NaN3), flash-frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C until used for total Aβ measurement. Soluble and total Aβ levels in the brain were measured by sandwich ELISA which used 6E10 monoclonal antibody as a capture antibody and two detection polyclonal antibodies R162 and R165 specific for Aβ40 and Aβ42, respectively. The assay was performed by an investigator (Pankaj Mehta) who was blinded to treatment group assignment. The levels of Aβ species are presented as μg of Aβ per g of wet brain, taking into account the dilution during brain homogenization and extraction procedures.

Oligomeric Aβ (o-Aβ) levels were determined with the Biosensis Oligomeric Amyloid-Beta ELISA kit (Biosensis, Thebarton, South Australia) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, the unknown concentrations of o-Aβ in samples were measured against a standard containing different concentrations of o-Aβ. Samples diluted in the provided diluent buffer were incubated for 24 hrs at 2–8 °C allowing the Aβ to bind to the pre-coated capture antibody (MOAB-2), followed by extensive washing and incubation for 1 hr at RT with biotin conjugated detection antibody (same as the capture antibody) which binds to the immobilized o-Aβ. After removal of excess antibody, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin (SAV-HRP) was added to incubate for 30 min, followed by washing, and a tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate incubation which resulted in a colorimetric solution. The intensity of this colored product is directly proportional to the concentration of o-Aβ in the sample. The TMB reaction was stopped and the absorbance of each well was read at 450 nm. The standards provided a linear curve and the best-fit line determined by linear regression were used to calculate the concentration of Aβ oligomers in the samples

Western blot analysis of Aβ oligomers

Brain homogenates were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 hr at 4 °C. The supernatants were collected and the total protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA; Pierce, Rockford, IL). Equal aliquots of protein from each sample, mixed with an equal volume of Tricine sample buffer, were subjected to overnight electrophoresis on 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide Tris-tricine gels under non-reducing conditions. Following overnight electrophoresis proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (BioRad, CA) for 1 h at 400 mA using CAPS buffer (3-cyclohexylamino-1-propanesulfonic acid) containing 10% methanol. The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBST (Tris, 10 mM; NaCl, 150 mM; Tween20, 0.1%, pH 7.5) for 1 hr at room temperature and then incubated with monoclonal antibodies 4G8/6E10 diluted 1:5000 for 1 hr. The antigen–antibody complexes were detected by horseradish peroxidase–conjugated sheep anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody at 1:5,000 dilution (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, NC) and visualized using SuperSignal (Pierce Chemical, IL) on X-Omat Blue XB-1 autoradiography film (Eastman Kodak Company, New Haven, CT). Autoradiographs were digitized and subjected to densitometric analysis using ImageJ software v1.34 (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Measurement of levels of plasma cholesterol

Plasma cholesterol level was measured by using a Cholesterol E kit (Wako Diagnostics, Richmond, VA)45. The Cholesterol E is an enzymatic colorimetric method for the quantitative determination of total cholesterol in the blood.

Statistical Analysis

Object recognition data were analyzed by using paired, two tailed t test. Data from the radial arm maze and Thioflavin-T assay were analyzed by two-way repeated measures ANOVA. All other sensorimotor test, histological and biochemical measurements between groups were analyzed by using the unpaired Student’s t test with Welch’s correction following confirmation of normal data distribution by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 (Graphpad, San Diego, CA).

Results

Studies of CPO_Aβ17-21 P in Vitro

We designed 9 pairs of related linear and cyclic peptoids derived from Aβ12-28 P sequence to screen for new apoE/Aβ binding inhibitors with higher efficacy and safety (see Supplemental Figs 1 and 2 showing the structure of all tested peptoids). Surface Plasmon Resonance studies showed that three peptoid compounds CPO_Aβ17-21 P, CPO_Aβ17-21 and LPO_Aβ17-21 P inhibited apoE4/Aβ42 binding. CPO_Aβ17-21 P (Fig. 1a) produced the best inhibition of binding and was chosen as the lead peptoid for further testing. It has a molecular weight of 703.83 and a peptide-like backbone composed of only 5 peptoid units (Fig. 1a). There was a 50% inhibition of apoE4/Aβ42 binding (Fig. 1c) by the lead peptide, CPO_ Aβ17-21 P at a 2:1 molar ratio (peptoid:apoE4, blue line Fig. 1c) and a near complete inhibition at a 8:1 molar ratio (peptoid:apoE4, red line Fig. 1c). The half-maximal inhibition (IC50) derived from a one-site competition, nonlinear, regression equation of CPO_ Aβ17-21 P was 1.02 nM, calculated using GraphPad Prism 7.0 (Graphpad, San Diego, CA) (Fig. 1d), which is significantly better compared to our previously published IC50 (36.7 nM) of the Aβ17-28P16. Peptoids lack the hydrogen of secondary amides, and thus are unlikely to form β-sheet structures, which is associated with the toxicity of Aβ oligomers and Aβ derived peptides. Incubation of peptoid inhibitor CPO_Aβ17–21 P at 37 °C for 10days at concentrations up to 100 µM did not produce aggregates or fibrils, indicating that CPO_Aβ17–21 P is non-fibrillogenic in vitro (see purple line in Fig. 1e and f). Thioflavin T (ThT) aggregation assay of Aβ40 and apoE4 protein pre-incubated with peptoid inhibitor CPO_Aβ17-21 P at a 1 to 2 molar ratio (apoE4: inhibitor), and of Aβ42 and apoE4 pre-incubated with peptoid inhibitor CPO_Aβ17-21 P at a 1 to 2 molar ratio (apoE4: inhibitor), showed a significant inhibition of apoE4 mediated Aβ40 (p = 0.0034, by 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test comparing the Aβ40 + apoE4 + CPO_Aβ17-21 P versus Aβ40 + apoE4 curves) or Aβ42 (p = 0.0011, by 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test comparing the Aβ42 + apoE4 + CPO_Aβ17-21 P versus Aβ42 + apoE4 curves) in vitro aggregation (Fig. 1e and f). This degree of inhibition, by CPO_Aβ17–21 P, of Aβ40/42 aggregation enhancement by apoE4 was somewhat less compared to what we have previously reported with Aβ12-28 P16.

Molecular structure of peptoid CPO_Aβ17-21 P and its inhibitory effect on apoE4/Aβ 42 binding and reduction of apoE4 mediated Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrillization. (a) Molecular structure of the peptoid CPO_Aβ17-21 P. (b) Surface Plasmon Resonance assay of apoE4/Aβ42 binding. Binding of lipidated apoE4 is shown by the green line with the black line representing the reference. (c) Surface Plasmon Resonance assay of CPO_Aβ17-21 P inhibition of apoE4/Aβ42 binding at a 2:1 (blue line, peptoid:apoE4) and 8:1 molar ratio (red line, peptoid:apoE4), with the black line below each colored line representing the corresponding reference. (d) Shown is the half-maximal inhibition (IC50) of lipidated apoE/Aβ binding by increasing concentrations of CPO_Aβ17-21 P derived from a one-site competition, nonlinear, regression equation of CPO_ Aβ17-21 P was 1.02 nM, calculated using GraphPad Prism 7.0 (Graphpad, San Diego, CA). (e) and (f) Thioflavin T Aβ aggregation assay, showing inhibition of apoE4 potentiated Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibril formation when incubated with CPO_Aβ17-21 P. Solid red line shows the Aβ40 (400 µM, in e) or Aβ42 (100 µM, in f) fibril formation increment when incubated with recombinant apoE4 at 100:1 molar ratio. Dashed red line shows reduction of fibril formation on Aβ40 (in (e) and Aβ42 (in f) when apoE4 was pre-incubated with peptoid CPO_Aβ17-21 P. Green line shows Aβ40 (in e) and Aβ42 (in f) alone, blue line indicates Aβ40 or Aβ42 incubated with peptoid, brown line indicates apoE4 alone and purple line shows peptoid CPO_Aβ17-21 P. Repeated measures analysis of variance followed by a Tukey post-hoc multiple comparison analysis showed p < 0.0001 for difference between group; Aβ40 + apoE4 + CPO_Aβ17-21 P versus Aβ40 + apoE4 p = 0.0034; Aβ42 + apoE4 + CPO_Aβ17-21 P versus Aβ42 + apoE4 p = 0.0011; no significant difference between Aβ40 + CPO_Aβ17-21 P and Aβ40 alone; no significant difference between Aβ42 + CPO_Aβ17-21 P and Aβ42 alone were found.

CPO_AB17-21P cytotoxicity was tested by MTS cell viability assays in human (SK-N-SH) and in mouse (N2a) neuroblastoma cell models. CPO_Aβ17–21 P is nontoxic to cells treated for 24 hrs at concentrations of 0.1 µM to 10 µM (Fig. 2a and b). In human SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells, the apoE4-enhanced cytotoxicity of Aβ42 is neutralized by pre-incubation of apoE4 with binding inhibitors CPO_Aβ17–21 P or Aβ12-28 P (Fig. 2c). Under the same condition, CPO_Aβ17–21 P (**p < 0.01) has a greater apoE4 neutralization effect compared to Aβ12-28 P (*p < 0.05). A higher ratio of CPO_Aβ17–21 P to apoE4 pre-incubation treatment was associated with enhanced rescue effects on SK-N-SH cells, indicating greater apoE4 inhibition, which mirrors the SPR results.

Cytotoxicity of peptoid CPO_ Aβ17-21 P on SK-N-SH human neuroblastoma cells and mouse N2a neuroblastoma cells and inhibition of Aβ42/apoE4 cytotoxicity by pre-incubation of apoE4 with CPO_Aβ17-21 P. (a) CellTiter-Blue® cytotoxicity assay showing no significant differences between vehicle and CPO_ Aβ17-21 P at 0.1, 1 and 10 µM. on human SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells or on (b) mouse N2a neuroblastoma cells. (c) Toxicity effect of Aβ42 on human SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells and potentiation of toxicity in presence of apoE4. CPO_ Aβ17-21 P peptoid reduces significantly the toxicity of Aβ42/apoE4 at 1 and 4 µM (**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05).

Studies of CPO_Aβ17-21 P in APP/PS1 AD Model Mice

Behavioral studies

The APP/PS1 AD mouse is a model of cerebral amyloidosis, that rapidly develops amyloid associated pathologies with a robust gliosis and thus facilitates a quick readout of therapeutic effects. To test the in vivo therapeutic effects of the lead peptoid, CPO_ Aβ17-21 P, we systematically treated APP/PS1 AD mice twice a week for four months with 0.20 mg of CPO_Aβ17-21 P per mouse (n = 11, 5 male, 6 female) or with vehicle saline (n = 10, 5 male, 5 female) as a control. Sensorimotor and cognitive testing of the APP/PS1 AD mice receiving CPO_AB17-21P or vehicle revealed no observable differences or anomalies in rotarod and locomotor activities (Fig. 3a–c). APP/PS1 AD mice treated with CPO_Aβ17–21 P showed a significant cognitive improvement as measured by radial arm maze (Fig. 3d; **p < 0.01 by two-way ANOVA for treatment effect) and novel object recognition (Fig. 3e; *p = 0.016), two standard cognitive tests. There was no significant difference between APP/PS1 AD mice treated with CPO_Aβ17–21 P and controls in latency measurements during the radial arm maze testing by two-way ANOVA (p = 0.09 for treatment effect, p = 0.0018 for days effect; data not shown).

Cognitive testing and locomotor assessment of APP/PS1 mice treated with peptoid CPO_ Aβ17-21 P. (a) Rotarod and (b) Traverse beam locomotor tests showing no significant differences between vehicle group and mice treated with the peptoid (p > 0.05). (c) Open field locomotor test results showing no significant differences in distance traveled, resting time, maximum velocity and average speed between vehicle group and peptoid treated mice (p > 0.05, two-tailed unpaired t-test). (d) Radial arm maze. Number of errors plotted versus number of days. Significant differences between vehicle mice group and mice treated with the peptoid (**p < 0.01, by two-way ANOVA for treatment effect). (e) Object recognition test showing the average time spent with the familiar and novel objects. Significant differences in the time that treated mice spent with the novel object compared to the vehicle group (*p < 0.05, two-tailed paired t-test). There was no significant difference between the time spent with the familiar and novel objects in the vehicle control group.

Biochemical and immunohistochemical studies

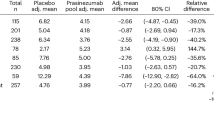

This cognitive improvement was associated with reduction of insoluble and soluble Aβ peptide/oligomer levels in the brain (Fig. 4a and b), as well as reduction of total amyloid burden assessed by immunohistochemical analysis in both the cortex (p = 0.0226) and the hippocampus (p = 0.0361) (Fig. 5). Significantly, treatment with CPO_Aβ17-21 P reduced oligomer levels, the species most linked to neuronal toxicity46 (Fig. 4c and e). A potential risk of therapeutic approaches that target Aβ deposition involves elevated levels of soluble Aβ which may enhance formation of toxic oligomer species. We demonstrate that at least in this model, this is not the case. We also determined if CPO_Aβ17–21 P treatment effected plasma total cholesterol levels. There was no significant difference in the plasma total cholesterol level between vehicle and CPO_Aβ17–21 P treated mice (Fig. 4d).

Reduction of soluble and insoluble Amyloid-β levels on APP/PS1 mice treated with peptoid CPO_ Aβ17-21 P. (a) Reduction of Aβ40 in the soluble fraction extracted with diethylamine (DEA) from APP/PS1 mice brain homogenates (***p < 0.001, two-tailed unpaired t-test). (b) Reduction of Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in the insoluble fraction extracted with formic acid (FA) (***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001 respectively, two-tailed unpaired t-test). (c) Reduction of Aβ oligomeric species measured by ELISA assay (*p < 0.05, two-tailed unpaired t-test). (d) Plasma cholesterol levels on APP/PS1 mice treated with peptoid CPO_ Aβ17-21 P (p > 0.05, two-tailed unpaired t-test). (e) Reduction of Aβ oligomeric species shown by western blot with anti-amyloid antibody 4G8 on APP/PS1 mice brain homogenates (*p < 0.05, two-tailed unpaired t-test).

Amyloid-β plaque burden on brains of APP/PS1 mice treated with peptoid CPO_ Aβ17-21 P or vehicle alone. (a) Treatment with CPO_ Aβ17-21 P decreased cortical and hippocampal burden in APP/PSI mice. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (b) There was a significant reduction observed in 6E10/4G8 immunoreactivity in both cortex and hippocampus in the CPO_ Aβ17-21 P treated mice versus vehicle treated mice, *p < 0.05, one-tailed unpaired t-test.

Another potential risk in targeting Aβ deposition is exacerbated brain inflammation with resultant neuronal dysfunction/death. Our studies document that immunoreactivity of GFAP (Fig. 6a and b), CD11b (Fig. 6c and d) and Iba1 (Fig. 6e and f), biomarkers for microgliosis (Iba1 and CD11b) and astrogliosis (GFAP), are unchanged (with a trend for reduction) or are significantly reduced in the CPO_Aβ17-21 P treated Tg mice versus vehicle mice (Fig. 6).

Levels of reactive astrocytes and microglia in brains from APP/PS1 mice treated with CPO_ Aβ17-21 P or vehicle. (a) Treatment with CPO_ Aβ17-21 P had no significant effect on cortical astrogliosis, but it was associated with decreased hippocampal astrogliosis in APP/PS1 mice, (b) as quantified by GFAP immunoreactivity. (c) Treatment with CPO_ Aβ17-21 P decreased cortical, but had no significant effect on hippocampal microgliosis in APP/PS1 mice, (d) as quantified by CD11b immunoreactivity, (e) CPO_ Aβ17-21 P treatment reduced microgliosis in the cortex, but had no significant effect on hippocampal microgliosis of APP/PS1 mice, (f) as quantified by Iba1 immunoreactivity, (Scale bars represent 100 μm.*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, one-tailed unpaired t-test).

Discussion

The apoE/Aβ interaction plays a key role in the conformational transformation of soluble Aβ and Aβ deposits in AD brains3, 5, 47, 48. ApoE has multiple important normal functions in the brain, being the major CNS cholesterol and other lipid carrier, as well as being involved in synaptic plasticity, glucose metabolism, mitochondrial function, and vascular integrity4, 48. In AD apoE influences both the aggregation state and clearance of Aβ in an isotype specific manner3, 5, 48,49,50. ApoE has been shown to enhance aggregation of Aβ with apoE4 > apoE3 > apoE28, 9, 33, 51, as well having effects on the stabilization of Aβ oligomers with apoE4 having the greatest impact52, 53. Under physiological conditions, relatively little normal, soluble Aβ (sAβ) is bound to apoE15, with the major CNS Aβ binding protein being apoJ54, 55. However, in AD with the shift in the aggregate state of Aβ, there is more interaction with apoE12, 50, 56. It has also been shown that apoE4 is less effective at clearance of Aβ compared to apoE357. Hence it might be suggested that a strategy of blocking the binding between apoE and Aβ might promote Aβ deposition, as it would inhibit clearance. Pivotal in vivo studies have shown that this is not the case. Knock out of apoE greatly reduces fibrillar amyloid deposition58, with apoE4 expressing AD transgenic mice have greater amyloid deposition compared to apoE3 or E2 expressing mice59, 60. Other Aβ binding proteins such as apoJ or α2-macroglobulin are associated with pathways that are much more effective at Aβ clearance compared to clearance of Aβ/apoE complexes3, 49, 50, 61. Hence the net effect of blocking the Aβ/apoE interaction is to inhibit deposition and enhance clearance. In addition, this strategy has the benefit of not interfering with the many normal and beneficial functions of apoE. In prior studies we showed that treatment with Aβ 12-28 P, a peptide homologous to the specific apoE binding domain of Aβ in two AD Tg mouse models with primarily amyloid plaque deposition and in one AD model with primarily CAA resulted in a significant reduction of Aβ burden in both brain parenchyma and in brain vessels compared to age matched vehicle-treated Tg mice16,17,18. We also demonstrated that blocking the apoE/Aβ interaction with Aβ12-28 P in triple transgenic mice ameliorates AD related Aβ and tau pathology19. Aβ12-28 P treatment in an amyloid mouse model with apoE2-TR or apoE4-TR mouse background resulted in Aβ oligomer and plaque load reduction and alleviated neuritic degeneration indicating that inhibition of Aβ/apoE interaction appears to effectively block aggregation and deposition of Aβ, regardless of apoE isoform20.

In our current study to advance our novel approach towards clinical application, we designed 9 pairs of related linear and cyclic peptoid compounds derived from the Aβ12-28 P sequence to screen for new apoE/Aβ binding inhibitors with a potentially higher efficacy and safety. The lead peptoid screened by SPR, CPO_Aβ17-21 P decreased the apoE4/Aβ42 binding at a 2:1 molar ratio (peptoid:apoE4) and almost completely blocked binding at a 8:1 molar ratio (peptoid:apoE4). Significantly, the half-maximal inhibition (IC50) derived from a one-site competition, nonlinear, regression equation of CPO_Aβ17-21 P was 1.02 nM compared to 36.7 nM for the model peptide, Aβ12-28P16. Previous studies have shown that the critical region for Aβ binding to apoE corresponds to residues 17-21 with the lysine at residue 16 being particularly important62, 63. Hence it is not surprising that a peptoid corresponding to this sequence would be an effective inhibitor of the Aβ/apoE interaction.

We show this peptoid is non-fibrillar and Thioflavin T aggregation assay testing showed a significant inhibition of apoE mediated aggregation of Aβ. CPO_ Aβ17-21 P was not toxic in mouse N2a and human SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cell lines. Moreover CPO_ Aβ17-21 P is a more potent inhibitor of apoE-enhanced Aβ 42 cytotoxicity than Aβ12-28 P in human SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells. APP/PS1 AD mice treated with CPO_ Aβ17-21 P had a significant cognitive improvement, reduction of soluble and insoluble Aβ peptide/oligomer levels in brain and lower total amyloid burden in cortex and hippocampus. Importantly, CPO_ Aβ17–21 P treatment ameliorates Aβ related pathology and cognitive deficit using a 7.5 fold lower dose (0.2 mg per mouse, twice per week) compared to the Aβ12-28 P treatment dose we previously used on 3xTg mice (1 mg per mice, three times per week)19. This argues that the new peptoid inhibitor CPO_Aβ17–21 P, with a very low molecular weight (<1 kDa) and inherently protease resistant compound, has better bioavailability/biostability compared to Aβ12-28 P.

A potential risk inherent in targeting Aβ deposition is increasing the pool of soluble Aβ which may potentiate formation of the toxic oligomer species, as has been shown for some immunotherapeutic approaches64. Although apoE has a dual role in Aβ deposition and clearance, CPO_Aβ17-21 P inhibition of apoE4/Aβ42 interaction in APP/PS1 AD mice did not affect the soluble Aβ pool. Brain inflammation is another potential risk when targeting Aβ deposition. Our studies show, that Iba1 and CD11b (both markers for microgliosis), and GFAP (a biomarker for astrogliosis) immunoreactivity is reduced or unchanged in the CPO_Aβ17-21 P treated Tg mice.

Currently, there is no effective therapy for AD, a highly prevalent, devastating neurodegenerative disease expected to increase in the future with the aging population1, 65. Our novel therapy of blocking apoE/Aβ interaction has ameliorated all the pathological features tested in the present study: improved memory deficits, reduction of amyloid burden and tau pathology and reduction of vascular amyloid deposition. A study which used Aβ12-28 P to block apoE/Aβ interaction in an amyloid mouse model with apoE2-TR or apoE4-TR mouse background resulted in Aβ plaque load and oligomer reduction and ameliorated neuritic degeneration20. Thus this therapy is not apoE isoform restrictive. This approach does not preclude concomitant therapies which may have a synergistic effect that procures an effective treatment. Our current study provides further evidence that targeting the apoE/Aβ interaction is an attractive and viable therapeutic approach3, 7.

References

Scheltens, P. et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 388, 505–517, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01124-1 (2016).

Selkoe, D. J. & Hardy, J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med 8, 595–608, doi:10.15252/emmm.201606210 (2016).

Potter, H. & Wisniewski, T. Apolipoprotein E: essential catalyst of the Alzheimer amyloid cascade. Int. J. Alz. Dis 2012, 489428 (2012).

Huang, Y. & Mahley, R. W. Apolipoprotein E: structure and function in lipid metabolism, neurobiology, and Alzheimer’s diseases. Neurobiol Dis 72 Pt A, 3–12, doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2014.08.025 (2014).

Huynh, T. V., Davis, A. A., Ulrich, J. D. & Holtzman, D. M. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer Disease: The influence of apoE on amyloid-beta and other amyloidogenic proteins. J Lipid Res, doi:10.1194/jlr.R075481 (2017).

Liao, F., Yoon, H. & Kim, J. Apolipoprotein E metabolism and functions in brain and its role in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Lipidol 28, 60–67, doi:10.1097/MOL.0000000000000383 (2017).

Yamazaki, Y., Painter, M. M., Bu, G. & Kanekiyo, T. Apolipoprotein E as a Therapeutic Target in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of Basic Research and Clinical Evidence. CNS Drugs 30, 773–789, doi:10.1007/s40263-016-0361-4 (2016).

Wisniewski, T. & Frangione, B. Apolipoprotein E: a pathological chaperone protein in patients with cerebral and systemic amyloid. Neurosci. Lett 135, 235–238 (1992).

Ma, J., Yee, A., Brewer, H. B. Jr., Das, S. & Potter, H. Amyloid-associated proteins alpha 1-antichymotrypsin and apolipoprotein E promote assembly of Alzheimer beta-protein into filaments. Nature 372, 92–94 (1994).

Ma, J., Brewer, B. H., Potter, H. & Brewer, H. B. Jr. Alzheimer Aβ neurotoxicity: promotion by antichymotrypsin, apoE4; inhibition by Aβ-related peptides. Neurobiol. Aging 17, 773–780 (1996).

Sanan, D. A. et al. Apolipoprotein E associates with beta amyloid peptide of Alzheimer’s disease to form novel monofibrils. Isoform apoE4 associates more efficiently than apoE3. J. Clin. Invest 94, 860–869 (1994).

Golabek, A. A., Marques, M., Lalowski, M. & Wisniewski, T. Amyloid β binding proteins in vitro and in normal human cerebrospinal fluid. Neurosci. Lett 191, 79–82 (1995).

Golabek, A. A., Soto, C., Vogel, T. & Wisniewski, T. The interaction between apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide is dependent on β-peptide conformation. J. Biol. Chem 271, 10602–10606 (1996).

Wu, M., He, Y., Zhang, J., Yang, J. & Qi, J. Co-injection of Abeta1-40 and ApoE4 impaired spatial memory and hippocampal long-term potentiation in rats. Neurosci Lett 648, 47–52, doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2017.03.043 (2017).

Verghese, P. B. et al. ApoE influences amyloid-beta (Abeta) clearance despite minimal apoE/Abeta association in physiological conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E1807–E1816 (2013).

Sadowski, M. et al. A synthetic peptide blocking the apolipoprotein E/beta-amyloid binding mitigates beta-amyloid toxicity and fibril formation in vitro and reduces beta-amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Am J Pathol 165, 937–948 (2004).

Sadowski, M. et al. Blocking the apolipoproteinE/Amyloid β interaction reduces the parenchymal and vascular amyloid-β deposition and prevents memory deficit in AD transgenic mice. PNAS 103, 18787–18792 (2006).

Yang, J. et al. Blocking the apolipoprotein E/amyloid β interaction reduces fibrillar vascular amyloid deposition and cerebral microhemorrhages in TgSwDI mice. J Alzheimers. Dis 24, 269–285 (2011).

Liu, S. et al. Blocking the apolipoprotein E/amyloid β interaction in triple transgenic mice ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease related amyloid β and tau pathology. J. Neurochem 128, 591 (2014).

Pankiewicz, J. E. et al. Blocking the apoE/Abeta interaction ameliorates Abeta-related pathology in APOE epsilon2 and epsilon4 targeted replacement Alzheimer model mice. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2, 75, doi:10.1186/s40478-014-0075-0 (2014).

Cho, S., Choi, J., Kim, A., Lee, Y. & Kwon, Y. U. Efficient solid-phase synthesis of a series of cyclic and linear peptoid-dexamethasone conjugates for the cell permeability studies. J Comb. Chem 12, 321–326 (2010).

Khan, S. N., Kim, A., Grubbs, R. H. & Kwon, Y. U. Ring-closing metathesis approaches for the solid-phase synthesis of cyclic peptoids. Org. Lett 13, 1582–1585 (2011).

Park, S. & Kwon, Y. U. Facile solid-phase parallel synthesis of linear and cyclic peptoids for comparative studies of biological activity. ACS combinatorial science 17, 196–201, doi:10.1021/co5001647 (2015).

Dohm, M. T., Kapoor, R. & Barron, A. E. Peptoids: Bio-Inspired Polymers as Potential Pharmaceuticals. Curr. Pharm. Des (2011).

Mandity, I. M. & Fulop, F. An overview of peptide and peptoid foldamers in medicinal chemistry. Expert Opin Drug Discov 10, 1163–1177, doi:10.1517/17460441.2015.1076790 (2015).

Stine, W. B., Jungbauer, L., Yu, C. & LaDu, M. J. Preparing synthetic Abeta in different aggregation states. Methods Mol. Biol 670, 13–32, doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-744-0_2 (2011).

Kwon, Y. U. & Kodadek, T. Encoded combinatorial libraries for the construction of cyclic peptoid microarrays. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 5704–5706 (2008).

Masters, C. L. et al. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 82, 4245–4249 (1985).

Prelli, F., Castaño, E. M., Glenner, G. G. & Frangione, B. Differences between vascular and plaque core amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem 51, 648–651 (1988).

Naslund, J. et al. Relative abundance of Alzheimer Aβ amyloid peptide variants in Alzheimer disease and normal aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 91, 8378–8382 (1994).

Mori, H., Takio, K., Ogawara, M. & Selkoe, D. J. Mass spectroscopy of purified amyloid β protein in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biol. Chem 267, 17082–17086 (1992).

McGowan, E. et al. Abeta42 is essential for parenchymal and vascular amyloid deposition in mice. Neuron 47, 191–199 (2005).

Wisniewski, T., Castaño, E. M., Golabek, A. A., Vogel, T. & Frangione, B. Acceleration of Alzheimer’s fibril formation by apolipoprotein E in vitro. Am. J. Pathol 145, 1030–1035 (1994).

Holcomb, L. et al. Accelerated Alzheimer-type phenotype in transgenic mice carrying both mutant amyloid precursor protein and presenilin 1 transgenes. Nature Medicine 4, 97–100 (1998).

Goni, F. et al. Immunomodulation targeting both Aβ and tau pathological conformers ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease pathology in TgSwDI and 3xTg mouse models. Journal of Neuroinflammation 10, 150 (2013).

Scholtzova, H. et al. Toll-like receptor 9 stimulation for reduction of amyloid β and tau Alzheimer’s disease related pathology. Acta Neuropathol. Commun 2, 101 (2014).

Scholtzova, H. et al. Innate Immunity Stimulation via Toll-Like Receptor 9 Ameliorates Vascular Amyloid Pathology in Tg-SwDI Mice with Associated Cognitive Benefits. J Neurosci 37, 936–959, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1967-16.2017 (2017).

Kim, K. S. et al. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies reactive to synthetic cerebrovascular amyloid peptide. Neurosci. Res. Comm 2, 121–130 (1988).

Goni, F., Peyser, D., Herline, K., Sun, Y. & Wisniewski, T. Monoclonal antibody therapy targeting the shared pathological conformer of both beta-amyloid and hyperphosphorylated tau. Alz. Dementia 9, P839 (2013).

Scholtzova, H. et al. Innate immunity stimulation via TLR9 in a non-human primate model of sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Alz. Dementia 9, p508 (2013).

Morgan, D., Gordon, M. N., Tan, J., Wilcock, D. & Rojiani, A. M. Dynamic complexity of the microglial activation response in transgenic models of amyloid deposition: implications for Alzheimer therapeutics. J Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol 64, 743–753 (2005).

Streit, W. J., Braak, H., Xue, Q. S. & Bechmann, I. Dystrophic (senescent) rather than activated microglial cells are associated with tau pathology and likely precede neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 118, 475–485 (2009).

Zotova, E. et al. Inflammatory components in human Alzheimer’s disease and after active amyloid-beta42 immunization. Brain 136, 2677–2696 (2013).

Schmidt, S. D., Nixon, R. A. & Mathews, P. M. ELISA method for measurement of amyloid-beta levels. Methods Mol. Biol 299, 279–297 (2005).

Trogan, E. et al. Gene expression changes in foam cells and the role of chemokine receptor CCR7 during atherosclerosis regression in ApoE-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 3781–3786, doi:10.1073/pnas.0511043103 (2006).

Viola, K. L. & Klein, W. L. Amyloid beta oligomers in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis, treatment, and diagnosis. Acta Neuropathol 129, 183–206 (2015).

Liu, C. C., Kanekiyo, T., Xu, H. & Bu, G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat. Rev. Neurol 9, 106–118 (2013).

Zhao, N., Liu, C. C., Qiao, W. & Bu, G. Apolipoprotein E, Receptors, and Modulation of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biol Psychiatry, doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.03.003 (2017).

Bell, R. D. et al. Transport pathways for clearance of human Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide and apolipoproteins E and J in the mouse central nervous system. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 27, 909–918, doi:10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600419 (2007).

Han, S. H., Park, J. C. & Mook-Jung, I. Amyloid beta-interacting partners in Alzheimer’s disease: From accomplices to possible therapeutic targets. Prog Neurobiol 137, 17–38, doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.12.004 (2016).

Castaño, E. M. et al. Fibrillogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease of amyloid beta peptides and apolipoprotein E. Biochem. J 306, 599–604 (1995).

Hashimoto, T. et al. Apolipoprotein E, especially apolipoprotein E4, increases the oligomerization of amyloid beta peptide. J Neurosci 32, 15181–15192, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1542-12.2012 (2012).

Garai, K., Verghese, P. B., Baban, B., Holtzman, D. M. & Frieden, C. The binding of apolipoprotein E to oligomers and fibrils of amyloid-beta alters the kinetics of amyloid aggregation. Biochemistry 53, 6323–6331, doi:10.1021/bi5008172 (2014).

Calero, M. et al. Apolipoprotein J (clusterin) and Alzheimer’s disease. Microsc Res Tech 50, 305–315, doi:10.1002/1097-0029(20000815)50:4<305::AID-JEMT10>3.0.CO;2-L (2000).

Matsubara, E., Frangione, B. & Ghiso, J. Characterization of apolipoprotein J-Alzheimer’s A beta interaction. J. Biol. Chem 270, 7563–7567 (1995).

Wisniewski, T., Lalowski, M., Golabek, A. A., Vogel, T. & Frangione, B. Is Alzheimer’s disease an apolipoprotein E amyloidosis? Lancet 345, 956–958 (1995).

Castellano, J. M. et al. Human apoE isoforms differentially regulate brain amyloid-beta peptide clearance. Sci. Transl. Med 3, 89ra57 (2011).

Bales, K. R. et al. Lack of apolipoprotein E dramatically reduces amyloid β-peptide deposition. Nature Gen 17, 263–264 (1997).

Tai, L. M., Youmans, K. L., Jungbauer, L., Yu, C. & Ladu, M. J. Introducing Human APOE into Abeta Transgenic Mouse Models. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2011, 810981, doi:10.4061/2011/810981 (2011).

Youmans, K. L. et al. APOE4-specific changes in Abeta accumulation in a new transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 287, 41774–41786, doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.407957 (2012).

Lauer, D., Reichenbach, A. & Birkenmeier, G. Alpha 2-macroglobulin-mediated degradation of amyloid beta 1–42: a mechanism to enhance amyloid beta catabolism. Exp Neurol 167, 385–392, doi:10.1006/exnr.2000.7569 (2001).

Liu, Q. et al. Mapping ApoE/Abeta binding regions to guide inhibitor discovery. Mol. Biosyst 7, 1693–1700 (2011).

Deroo, S. et al. Chemical cross-linking/mass spectrometry maps the amyloid beta peptide binding region on both apolipoprotein E domains. ACS Chem Biol 10, 1010–1016, doi:10.1021/cb500994j (2015).

Hara, H. et al. An Oral Abeta Vaccine Using a Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Vector in Aged Monkeys: Reduction in Plaque Amyloid and Increase in Abeta Oligomers. J Alzheimers Dis 54, 1047–1059, doi:10.3233/JAD-160514 (2016).

Drummond, E. & Wisniewski, T. Alzheimer’s disease: experimental models and reality. Acta Neuropathol 133, 155–175, doi:10.1007/s00401-016-1662-x (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH (grants: NS073502 and AG008051 to T.W.) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (grants: 2012R1A1A2006417 and 2015R1D1A1A01060628 to Y.U.K.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. performed experiments and helped write the manuscript. S.P. was involved in peptoid synthesis. G.A. helped perform biochemical experiments. F.P. performed surface plasmon resonance experiments and helped with editing the manuscript. Y.S. took care of the transgenic mice used in the experiments. M.M.A. help perform immunohistochemical experiments and with the preparation of figures. H.S. helped with quantitation of immunohistochemical findings. G.B. was involved in peptoid synthesis. B.B. helped with immunohistochemical studies. P.B.V. provided the lipidated apoE3 and apoE4 preparations. P.D.M. performed blinded measurements of Aβ40 and Aβ42. Y.U.K. performed peptoid synthesis. T.W. conceived and supervised the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Park, S., Allington, G. et al. Targeting Apolipoprotein E/Amyloid β Binding by Peptoid CPO_Aβ17-21 P Ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease Related Pathology and Cognitive Decline. Sci Rep 7, 8009 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08604-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08604-8

This article is cited by

-

Imipramine and olanzapine block apoE4-catalyzed polymerization of Aβ and show evidence of improving Alzheimer’s disease cognition

Alzheimer's Research & Therapy (2022)

-

ApoE4: an emerging therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease

BMC Medicine (2019)

-

Radiochemical examination of transthyretin (TTR) brain penetration assisted by iododiflunisal, a TTR tetramer stabilizer and a new candidate drug for AD

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Immunotherapy to improve cognition and reduce pathological species in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model

Alzheimer's Research & Therapy (2018)

-

Anti-β-sheet conformation monoclonal antibody reduces tau and Aβ oligomer pathology in an Alzheimer’s disease model

Alzheimer's Research & Therapy (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.