Abstract

The dinoflagellate-coral partnership influences the coral holobiont’s tolerance to thermal stress and bleaching. However, the comparative roles of host genetic versus environmental factors in determining the composition of this symbiosis are largely unknown. Here we quantify the heritability of the initial Symbiodinium communities for two broadcast-spawning corals with different symbiont transmission modes: Acropora tenuis has environmental acquisition, whereas Montipora digitata has maternal transmission. Using high throughput sequencing of the ITS-2 region to characterize communities in parents, juveniles and eggs, we describe previously undocumented Symbiodinium diversity and dynamics in both corals. After one month of uptake in the field, Symbiodinium communities associated with A. tenuis juveniles were dominated by A3, C1, D1, A-type CCMP828, and D1a in proportional abundances conserved between experiments in two years. M. digitata eggs were predominantly characterized by C15, D1, and A3. In contrast to current paradigms, host genetic influences accounted for a surprising 29% of phenotypic variation in Symbiodinium communities in the horizontally-transmitting A. tenuis, but only 62% in the vertically-transmitting M. digitata. Our results reveal hitherto unknown flexibility in the acquisition of Symbiodinium communities and substantial heritability in both species, providing material for selection to produce partnerships that are locally adapted to changing environmental conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coral bleaching, defined as either the loss of Symbiodinium cells from coral tissues or reduction in symbiont photosynthetic pigments, represents a threat to coral reefs world-wide as it increases in both frequency and magnitude1,2,3,4. If coral reefs are to persist under climate change, corals must either disperse to new unaffected habitats, acclimate through phenotypic plasticity, and/or adapt through evolutionary mechanisms5. However, the extent to which thermal tolerance can increase, either through changes to the host genome or Symbiodinium community hosted, or by direct selection on the symbionts themselves, is currently unclear.

Bleaching sensitivity is variable within and among species6, but comparative roles of host genetics versus symbiont communities to this variation remain unclear7, 8. The Symbiodinium community hosted by corals has long been recognized as the primary factor determining bleaching susceptibility8, 9. However, host influences are also evident10,11,12 and may play an equally important role in determining bleaching susceptibility. Endosymbiotic communities could influence host adaptation to changing climates through increased host niche expansion13, 14, but a major impediment to understanding the capacity of corals to adapt to a changing climate is lack of knowledge about the extent to which Symbiodinium communities associated with corals are inherited and hence subject to selection.

There are nine recognized Symbiodinium clades15 that encompass substantial sequence and functional variation at the intra-clade (type) level (reviewed in ref. 16). Deep sequencing technologies currently available can detect type level diversity even at low abundances17 and are now being applied to understand adult coral-Symbiodinium diversity18,19,20, but have not yet been applied to the early life-history stages of corals. Therefore, there are gaps in our basic knowledge of the composition of Symbiodinium communities at lower, functionally relevant taxonomic levels, particularly community members at background abundances, and in the eggs and juveniles of corals.

Natural variation in the composition of coral-associated Symbiodinium communities exists among coral populations and species16, 21, with certain communities offering greater bleaching resistance compared to others22, 23. It is not yet known what enhances or constrains the capacity of corals to harbour stress-tolerant Symbiodinium types and whether changes in Symbiodinium communities in response to environmental stressors are stochastic or deterministic24. Given the importance of Symbiodinium communities for bleaching susceptibility and mortality of the coral holobiont25, 26, quantifying the proportional contributions of genetic and environmental factors to community formation, regulation and stress tolerance is important for understanding coral health. If the Symbiodinium community is heritable, changes to these communities may bring about adaptation of the holobiont as a whole. Under this scenario, Symbiodinium community shifts are equivalent to changes in host allele frequencies, thus opening up new avenues for natural and artificial selection, assisted evolution and microbiome engineering24, 27.

Symbiodinium communities associated with scleractinian corals are either acquired from the environment (horizontal transfer) or passed maternally from adults to eggs or larvae (vertical transfer). Approximately 85% of scleractinian coral species broadcast spawn eggs and sperm into the environment, and of these, ~80% acquire symbionts horizontally; the remaining ~20% acquire them vertically28. Vertically-transmitted symbiont communities are predominantly found in brooding corals with internal fertilization28 and are theorized to be of lower diversity and higher fidelity16. Conversely, horizontal transmission has generally been assumed to result in weaker fidelity that can be increased through the development of strong genotype associations between hosts and their symbiont community29. Studies specifically quantifying the genetic component governing Symbiodinium communities established in offspring of both horizontal and vertical transmitters are needed to elucidate the potential for adaptation through symbiont community changes.

Heritability describes the genetic components of variability in a trait using analysis of co-variance among individuals with different relatedness30. The ratio of additive genetic variance to phenotypic variance (VA/VP) is defined as narrow-sense heritability (h2)31. The degree of heritability of a trait ranges from 0–1, and describes the influence of parental genetics on the variability of that trait31. Therefore, the degree to which traits might change from one generation to the next can be predicted from measures of heritability, where the predicted change in offspring phenotype is proportional to h2 (i.e., the breeder’s equation)32. It is particularly important to determine the genetic contribution to understand the potential for adaptation and to predict the strength of response to selection (i.e, the ‘evolvability’ of a trait)5, 33, 34.

To quantify the potential for selection of endosymbiotic Symbiodinium communities associated with broadcast spawning corals in response to changes in environmental conditions (i.e., climate change-induced), we characterized symbiont communities associated with adults and juveniles of the horizontal transmitter Acropora tenuis and with adults and eggs of the vertical transmitter Montipora digitata using high-throughput sequencing. Using a community diversity metric, we derived the narrow-sense heritability (h2) of these communities and identified new and unique Symbiodinium types recovered from juveniles and eggs compared to their parental colonies. Finally, we described previously unknown Symbiodinium community dynamics in the early life-history stages of these two common coral species.

Results

Symbiodinium communities associated with Acropora tenuis

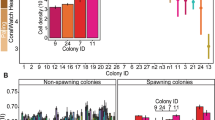

After one month in the field, there were similarities at the clade level between Symbiodinium communities associated with the 2012 and 2013 families of A. tenuis juveniles, with 54 OTUs (17.1%) shared between the two years, including similar proportions of OTUs retrieved across the clades in each year (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S4). In both years, the majority of OTUs were recovered from three clades (A, C, and D) and the number of OTUs from each of these clades was similar between years (Supplementary Table S4). The greatest diversity of OTUs found in juveniles from both years belonged to C1, A3 and “uncultured” types (see methods for definitions of OTUs), and a diversity of different OTUs within types A13, A-type CCMP828, D1 and D1a were also present (Supplementary Fig. S1). The predominant patterns characterising Symbiodinium communities associated with the 2012 and 2013 families were the high abundance of Symbiodinium types A3, C1, D1, and CCMP828, and the comparatively lower abundance of D1a (Fig. 2). However, substantial variation in Symbiodinium diversity and abundance existed among juveniles within the same family, as well as among families of juveniles (Supplementary Results, Fig. 2). For example, juvenile families differed in their average OTU diversity and abundance, as well as their taxonomic composition (additional description in Supplementary Results, Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S5), where particular families contained juveniles of particularly high diversity (families F14 and F18).

Circular trait plots of 261 Symbiodinium ITS-2 OTUs retrieved from Acropora tenuis juveniles and adults in 2012 (a) and 2013 (b). Plots include only those OTUs that were retrieved from three or more samples (134/422 OTUs in 2012 and 181/568 OTUs in 2013). Concentric circles from innermost to the outermost position represent OTUs present: (1) life-stage, (2) normalized abundance (principal: >0.01%, background <0.01%), and (3) ubiquity (core: >75% of samples, common: 25–75%, rare: <25%). OTU identity with an asterisk indicates it was retrieved in both years. Semi-transparent backgrounds represent clade designations of individual OTUs. See Supplementary Table S8 for full taxonomic information.

Barplots of variance-normalized abundances of Symbiodinium diversity associated with (a) juveniles and (b) adults of Acropora tenuis used in 2012 (Year 1) and 2013 (Year 2) crosses. Colours represent different Symbiodinium types. Origins of parent colonies are Orpheus and Wilkie reefs. A. tenuis adult colonies from Orpheus used for 2013 crosses included samples that were sequenced that represent the left side of the colony (L), center of the colony (C), and right side of the colony (R) to examine intra-colony Symbiodinium diversity.

Juveniles from both years harboured more unique OTUs than adults (juveniles vs. adults: 111 vs. 2 (2012), 151 vs. 2 (2013)), with comparatively few OTUs shared between life stages (21 shared in 2012 (out of 422 OTUs); 28 shared in 2013 (out of 568 OTUs)) (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the majority of OTUs in both years were at background abundances (Fig. 1). The majority of OTUs were also rare (112–172 OTUs found in less than 25% of samples in 2012 and 2013), whilst 4–16 OTUs were common (25–75% of samples) and 5–6 OTUs were core members (two A3 types, CCMP828, C1, D1, D1a were present in greater than 75% of samples) (Fig. 1).

Symbiodinium communities associated with Montipora digitata

101 OTUs were found M. digitata eggs and adults, with 7 (±0.9 SE) OTUs per egg and 5.3 (±0.9 SE) OTUs per adult, on average. The highest diversities of OTUs were retrieved from clades A (73 OTUs) and C (18 OTUs), whereas D had three OTUs represented (Fig. 3). 99.1% of the total cleaned reads belonged to C15 (OTU1), with this type making up 98.8% (±0.5 SE) and 99% (±0.1 SE) of all reads retrieved from dams and eggs, respectively. The next most abundant OTUs were C1, D1, and A3 (Fig. 4). Adults could generally be distinguished from eggs by the unique presence of A2, A3, particular C1 and A3 variants (C1_8, HA3–5), G3 (Fig. 3), and a greater proportional abundance of an A type symbiont (OTU4) in dams 29, 32, 7, 8 and 9 (Fig. 4). Of these unique adult OTUs, none were found in more than two adult colonies. Eighty-two OTUs were found in eggs but not adults and 43 of these were found in three or more eggs, and a majority were “uncultured” types at background levels from the eggs of dam 29 (Fig. 3). Both inter- and intra- family variation in background Symbiodinium OTU composition and abundance were detected within eggs as well (further description in Supplementary Results, Supplementary Fig. S2 and Supplementary Table S6).

Circular trait plots of 101 Symbiodinium ITS-2 OTUs retrieved from Montipora digitata eggs and adults. Concentric circles from innermost to the outermost position represent OTUs present: (1) life-stage, (2) normalized abundance (principal: >0.01%, background <0.01%), (3) ubiquity (core: >75% of samples, common: 25–75%, rare: <25%), and (4) dam identity. Semi-transparent backgrounds represent clade designations of individual OTUs. Red text indicates OTUs that were found in three or more eggs or adults. See Supplementary Table S8 for full taxonomic information.

Barplot of variance-normalized abundances of only the background Symbiodinium diversity associated with dams and eggs of Montipora digitata. Colours represent different Symbiodinium types. The dominant type, C15, was excluded for clarity. The first bar in each group is the spawning dam and the following bars represent her eggs. The tenth egg sample from dam 11 (M11) was made up of 100% C15, and was therefore not shown.

Narrow-sense heritability of Symbiodinium community in A. tenuis juveniles and M. digitata eggs

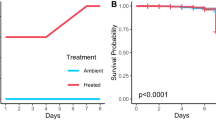

Bayesian linear mixed models, and specifically, the animal model, were used to estimate relatedness-based heritability as they are robust to unbalanced designs. Furthermore, the animal model utilizes all levels of relatedness between individuals in a given dataset, and not just parent-offspring comparisons35. The Bayesian narrow-sense heritability estimate (h2) of the initial Symbiodinium community in A. tenuis juveniles was 0.29, with a 95% Bayesian credibility interval for the additive genetic component of 0.06–0.86. The mean heritability was 0.36 (±0.21 SD) (Fig. 5). The high density of estimates between 0.2–0.4 within the posterior distribution of h2 suggests high statistical support around 0.29, despite the credibility interval being very large. The maternal transfer of Symbiodinium in the broadcast spawning coral M. digitata had a narrow-sense heritability estimate of 0.62 (0.27–0.86 95% Bayesian credibility interval), with a mean heritability of 0.57 (±0.16 SD) (Fig. 5). We did not detect an effect of maternal environment on similarities in Symbiodinium diversity among eggs or among juveniles. Models that included maternal effects arising from eggs developing in a shared environment (maternal environmental effects for both A. tenuis and M. digitata) were not significantly better than those that did not include maternal effects (DIC no effects < DIC maternal environmental effects included).

Mid-parent regression estimates for the 29 A. tenuis families from 2012 and 2013 indicated that trait-based h2 of the Symbiodinium community was 0.3 (Supplementary Fig. S3). Parent-offspring regression of the 99 M. digitata eggs genotyped from nine dams resulted in a heritability estimate of 0.16 (slope = 0.078 × 2 as a single parent) (Supplementary Fig. S4). Therefore, 30% and 16% of the measured variation in the Symbiodinium community in A. tenuis and M. digitata, respectively, was due to genetic differences among offspring.

Impact of intragenomic variation on heritability analysis

Simulating intragenomic variants in the M. digitata dataset yielded five intragenomic variant groups from clade A (IGV1_A: OTU_65/74/113/123/121; IGV2_A: 29/23/133; IGV3_A: 68/32; IGV4_A:61/70; IGV5_A: 56/75), and one from clade C (IGV6_C: 128/42). OTUs from clade D were not highly similar and correlation coefficients for the three clade F OTUs had relatively low correlation coefficients (0.3–0.6). The diversity metric and Bayesian MCMC heritability was re-calculated with these 16 OTUs collapsed into their respective six intragenomic variants. The resulting h2 estimate was slightly higher (0.5754 ± 0.157 compared to the original estimate of 0.5722 ± 0.157).

Discussion

Substantial heritability of the initial Symbiodinium community in early life history stages of both vertically- and horizontally-transmitting corals highlights the important role of host genetics in governing the composition of symbiont communities within their tissues. Surprisingly, mean Bayesian heritability estimates for initial Symbiodinium communities associated with juveniles of Acropora tenuis were moderate (0.29), but higher than expected given low levels of fidelity assumed for species with environmentally-acquired symbionts. Conversely, heritability estimates associated with eggs of Montipora digitata were high (0.62), but lower than expected given the high levels of fidelity expected for vertically-transmitted symbionts. Given that heritability is a quantifiable measure of the influence of genes compared to environmental factors in shaping phenotypes, both non-zero heritability estimates confirm that genes do influence the structuring of Symbiodinium communities in these two coral species. Although our results differ from expectations of fidelity and heritability based on current transmission paradigms in corals, they are consistent with studies that have demonstrated the role of host genetics in governing the composition of symbiotic bacterial communities in mammals, insects and other cnidarians36,37,38,39, as well as the abundance of bacteria in insects40 and humans41. Furthermore, these estimates are consistent with the characteristic hallmarks of host-controlled symbiont regulation. For example, Symbiodinium cells are enveloped in a host-derived symbiosome, with only a few (2–8) symbiont cells per host membrane42. This suggests that the coral host may regulate Symbiodinium on an almost individual cell basis, facilitating overall population regulation40 and potentially community composition within the holobiont. Thus, it is likely advantageous for the host’s molecular architecture governing the Symbiodinium community to be passed from one generation to the next. Importantly, the partial genetic regulation of Symbiodinium communities found here suggests that there is potential for the symbioses to evolve and adapt, and therefore to potentially develop ‘optimal’ symbiont-host partnerships under changing environmental conditions.

Our results provide the first in-depth picture of the complexity of the Symbiodinium community in A. tenuis juveniles during the initial month of uptake. No juveniles exclusively hosted a single clade or type, a result corroborated by lab and other field-based experimental studies43,44,45,46,47,48. Moreover, although the diversity measured here was much greater than values reported in previous studies, we found temporal stability in cladal diversity and abundances between the two years. It is possible that the temporal stability detected at the clade level within juveniles was in part due to the stability of locally available symbionts, either from the sediments or from the continual seeding of symbionts into local environments by resident symbiont-bearing cnidarians49. Such environmental variance is partitioned in the MCMC animal model (along with genetic effects due to relatedness) and hence accounted for in heritability estimates. Therefore, stability in the availability of environmental Symbiodinium and its subsequent impact on temporal stability of coral-associated Symbiodinium communities would be accounted for in heritability estimates. The unexpectedly high fidelity of the symbiont community, in conjunction with our heritability estimates, suggest strong host genetic – symbiont community associations, a result also implicated in studies comparing symbiosis fidelity across phylogenetic associations in Hydra, wasps, and primates29. Further work is needed to document Symbiodinium diversity in juveniles of broadcast spawning corals, as well as to elucidate molecular mechanisms regulating the establishment of this symbiosis.

Our conclusion of active host regulation based on heritability estimates, coupled with temporal stability in the relative proportions and numbers of OTUs within clades at principal and background levels between years, suggest that genetic regulation governing Symbiodinium communities extends to clades found at very low abundance. The roles of many background Symbiodinium types remain unclear and may be minor compared to principal types like A3, C1, and D1 when corals are healthy. However, Symbiodinium at background abundances can be important for coral health under sub-optimal environmental conditions. For example, fine scale dynamics of Symbiodinium communities (i.e., changes in relative abundance and/or diversity of only a fraction of types) impact host bleaching susceptibility, recovery and physiology23, 26, 50, 51. Growing evidence suggests that background types are important in several Symbiodinium-coral symbioses during recovery from stress (i.e. Acropora millepora and D-types23, Agaricia spp., M. annularis, M. cavernosa-D1a50, 52, Pocillopora damicornis, Stylophora pistilata-C_I:53)19, but may not be relevent for all (i.e. Acropora japonica- and S. voratum)53. A strong functional role of background Symbiodinium types would not be surprising given the functional importance of background bacterial lineages recently described for corals54, 55, but remains to be conclusively established for many coral-Symbiodinium associations.

The heritability signal derived from Bayesian models found for Symbiodinium communities associated with eggs of the vertically-transmitting coral M. digitata was predictably strong (62%) given that the dominant C15 OTU was harboured in adults and eggs at very high abundances. However, fidelity was less than expected given that eggs acquire Symbiodinium communities in the maternal environment. This lower than expected heritability signal is mirrored when the likenesses between dams and eggs are compared. For example, despite Symbiodinium C15 dominating symbiont communities in both eggs and dams, maternal transfer lacked precision in one dam in particular (dam 29), whose eggs had highly variable Symbiodinium communities that included “uncultured” OTUs, similar to previous reports for another species in this genus56. It should be noted that, on average, M. digitata dams transmitted C15 so that it comprised 99% of the Symbiodinium community in all eggs, suggesting that a larger heritability estimate might have been expected. The posterior distribution of the heritability estimates also suggests that the value could resolve to be larger with increased sampling (up to 0.85). However, the lower than expected heritability reflects the fact that all Symbiodinium in eggs were considered, not just the OTU in greatest abundance. Therefore, the presence of other symbionts (although in low abundance and number) lowered the heritability estimate. The incorporation of all Symbiodinium, and not just the numerically dominant one, in heritability calculations is ecologically relevant, given the important role that low abundance microbes have in coral physiology and stress tolerance (clade D Symbiodinium 57, 58, and bacteria54, 55).

There are many precedents for inexact maternal transfer of symbiont communities, and studies on insects show that vertical transmission is rarely perfect59 due to symbiont competition within hosts60. Such imprecision in maternal transfer is a product of fitness costs associated with the maintenance of superinfections (stable coexistence of multiple symbionts) and can be overcome if selection for coexistence is greater than costs associated with their maintenance60. Superinfections may provide a diversity of beneficial symbiont traits. For example, different symbionts provide different nutrients to host insects61. For M. digitata, imprecision may represent a bet-hedging strategy to maximise the likelihood that some offspring will survive when eggs are dispersed and encounter environments that are different to their parents. Although some of these background OTUs may represent random contaminants (i.e. symbionts attached to the outside of eggs), a majority of OTUs were found in three or more independent egg samples, suggesting that they indeed represent either relevant symbiont candidates or intragenomic variants retrieved from relevant symbiont candidates. However, it is unlikely that these OTUs are intragenomic variants given the clustering method and clustering identity threshold used in this study (Materials and Methods: Sequencing of Symbiodinium ITS-2 in egg, juvenile and adult coral samples). Although many of these background OTUs existed predominantly at less than 1% abundance in adults and eggs, it is feasible that these OTUs may grow in abundance to become dominant members of the community if environmental conditions change50, as was found for C.28 and C_I:53 in P. damicornis 19. This variation highlights potential flexibility in the M. digitata-Symbiodinium symbiosis, which may enable the host to vary its symbiotic partnerships in response to environmental change by benefitting from new host-symbiont combinations.

Surprisingly, much of the diversity found in M. digitata eggs was not present in parent colonies, similar to results reported for larvae of the brooding, vertically-transmitting coral Seriatopora hystrix (Quigley et al. in-review) and observed here between A. tenuis juveniles and adults (this study). Our results suggest that eggs acquire symbionts from sources external to the maternal transmission process. Mixed systems involving both vertical and horizontal transmission are known (e.g. bacteria in clams; reviewed in ref. 29) and have recently been demonstrated in brooding corals (Quigley et al. in-review). Given that the cellular machinery needed for recognition of appropriate Symbiodinium types42 would not be developed in egg cytoplasm, where Symbiodinium are present pre-fertilization62, eggs exposed to transient symbionts in the dam’s gastrovascular cavity or by parasitic Symbiodinium-containing vectors (e.g. ciliates63 and parasites)60 may retain these communities until recognition systems of eggs, larvae or juveniles mature. Interestingly, one type (OTU111) found in three eggs from dam 29 was identified as a free-living A type recovered from Japanese marine sediments (EU106364)64, supporting the hypothesis that such unique OTUs in eggs may represent non-symbiotic, potentially opportunistic symbionts. Further work is needed to determine what ecological roles these symbionts potentially fulfil and their systematic relationships. For example, a high number of “uncultured” types suggest considerable taxonomic uncertainly, as has been observed for clade E Symbiodinium (see discussion in ref. 65).

Maternal environmental effects, such as lipid contributions by dams, have well known effects on the early life stages of many marine organisms66. However, our Bayesian models were not significantly improved by the addition of dam identity, suggesting that significant heritability estimates are attributable to genetic effects and not due to maternal environmental effects35 or cytoplasmic inheritance67. Whilst we can only speculate about the exact mechanisms that are being inherited by offspring, likely candidates include those involved in recognition and immunity pathways42, with cell-surface proteins playing an important role in the selection of specific Symbiodinium strains by coral hosts68,69,70. For example, these may include Tachylectin-2-like lectins, which have been implicated in the acquisition of A3 and a D-type in A. tenuis 43, 71, 72. Indeed, suppression or modification of the immune response has often been implicated in the formation of Symbiodinium-cnidarian partnerships42, 73, 74. Although this has not yet been demonstrated in corals, human studies have shown that immune system characteristics underpin heritable components of the genome75 and at least 151 heritable immunity traits have been characterized, including 22 cell-surface proteins76.

Juvenile corals may be primed to take up specific Symbiodinium types through the transfer of genetic machinery that results in a by-product(s) that ensures juveniles are colonized by beneficial types and prevents colonization by unfavourable symbionts through competitive exclusion (e.g., maternal imprinting controlled by offspring loci67). Such by-products may be akin to amino acids, which have been shown to regulate the abundances of Symbiodinium populations77. Sugars have also been found to influence bacterial communities in corals78 and may have similar roles in regulating Symbiodinium communities. Trehalose, in particular, has been identified as an important chemical attractant between Symbiodinium and coral larvae and may help to regulate the early stages of symbiosis79. Human studies also provide examples of sugars (both maternal and offspring derived) that make infant intestines less habitable for harmful bacteria, setting up conditions for preferential colonization by favourable bacteria80. Bacterial diversity in cnidarian hosts can also be modulated through the production of antimicrobial peptides36 and bacterial quorum sensing behaviour81. Although neither of these mechanisms has been explored with respect to the regulation of Symbiodinium in corals, similar host/symbiont by-products may be influential in the regulation of Symbiodinium communities.

Heritability estimates based on parent-offspring regression and Bayesian MCMC methods were similar in A. tenuis but not in M. digitata. Differences between the estimates of these two methods for M. digitata may be due to the purely maternal basis of inheritance in this species, with the slope of parent-offspring regressions potentially more accurate for traits that are transmitted following sexual reproduction involving two parents. Alternatively, Bayesian MCMC methods, which do not rely on phenotypic information of parents, and instead only utilize information on relatedness among offspring and co-variances between them in the phenotypic trait being measured, may be more robust to a variety of different reproductive modes across organisms. Furthermore, outplanting juveniles to only one location may have introduced bias into the regression-based estimates, causing juveniles and adults from the OI location to appear more similar, potentially because they were exposed to similar environmental pools of symbionts, compared to juveniles from PCB parents. However, concordance between Bayesian (which do not rely on parental phenotypic information) and regression-based estimates suggests that this bias is negligible. Standard errors calculated in heritability studies are normally large5 but Bayesian MCMC methods are robust, as they allow for estimation of heritability and statistical support of that estimate directly from posterior distributions. Therefore, although credibility intervals calculated were large, high densities of posterior distributions around our heritability estimates signify that these values are the most probable compared to values at lower posterior densities. This Bayesian method for determining uncertainty is robust, especially compared to frequentist methods where standard errors are approximate5.

In conclusion, results presented here provide new insights into the role of host genetics and inheritance in governing Symbiodinium communities in corals. This information is important for determining the potential for host-symbiont partnerships to evolve. Variability in the symbiont community within and among families and evidence that variation is heritable, as supported by the moderate to high heritability estimates found, corroborate the likelihood that adaptive change is possible in this important symbiotic community. These results may also aid in the development of active reef restoration methods focused on assisted evolution of hosts and symbionts, in which targeted traits with moderate to high heritability increase the efficacy of breeding schemes. Adaptive change through heritable variation of symbionts is therefore another mechanism that corals may use to contend with current and future stressors, such as climate change.

Materials and Methods

Experimental breeding design and sample collection

For crossing experiments, gravid colonies of the horizontally-transmitting broadcast-spawning coral Acropora tenuis were collected in 2012 and 2013 from the northern (Princess Charlotte Bay (PCB): 13°46′44.544″S, 143°38′26.0154″E) and central Great Barrier Reef (GBR) (Orpheus Island: 18°39′49.62″S, 146°29′47.26″E).

In 2012, nine families of larvae were produced by crossing gametes from four corals (OI: A–B, PCB: C–D) on 2 December following published methods82. The nine gamete crosses excluded self-crosses (Supplementary Table S1). Larvae were stocked at a density of 0.5 larvae per ml in one static culture vessel per family in a temperature-controlled room set at 27 °C (ambient seawater temperature). Water was changed one day after fertilization and every two days thereafter with 1 µM filtered seawater at ambient temperature. To induce settlement, 25 settlement surfaces (colour-coded glass slides) were added to each larval culture vessel six days post-fertilization, along with chips of ground and autoclaved crustose coralline algae (CCA, Porolithon onkodes collected from SE Pelorus: 18°33′34.87″S, 146°30′4.87″E). The number of settled juveniles was quantified for each family, and then placed randomly within and among the three slide racks sealed with gutter guard mesh. The racks were affixed to star pickets above the sediments in Little Pioneer Bay (18°36′06.2″S, 146°29′19.1″E) 11 days post fertilization. Slide racks were collected 29 days later (11 January 2013), after which natural infection by Symbiodinium was confirmed with light microscopy. Juveniles from each cross were sampled (n = 6–240 juveniles/family, depending on survival rates), fixed in 100% ethanol and stored at −20 °C.

In 2013, 25 families were produced from gamete crosses among eight parental colonies: four from PCB and four from Orpheus Island (full details of colony collection, spawning, crossing and juvenile rearing in ref. 82 (Supplementary Table S2). Larvae were raised in three replicate cultures per family. Settlement was induced by placing autoclaved chips of CCA onto settlement surfaces, which were either glass slides, calcium carbonate plugs or the bottom of the plastic culturing vessel. Settlement surfaces with attached juveniles were deployed randomly, 19 days post fertilization, at the same location in Little Pioneer Bay as in 2012, and collected 26 days later. Samples of juveniles (n = 1–194 juveniles per family) were preserved and stored as in 2012.

Thirty-two gravid colonies of the vertically-transmitting broadcast spawner Montipora digitata were collected from Hazard Bay (S18°38.069′, E146°29.781′) and Pioneer Bay (S18°36.625′, E146°29.430′) at Orpheus Island on the 30th of March and 1st of April 2015. Colonies were placed in constant-flow, 0.5 µM filtered seawater in outdoor raceways at Orpheus Island Research Station. Egg-sperm bundles were collected from a total of nine colonies on the 4th and 5th of April, separated with a 100 µm mesh and rinsed three times. Individual eggs and adult tissue samples were then placed in 100% ethanol and stored at −20 °C until processing.

Sequencing of Symbiodinium ITS-2 in egg, juvenile and adult coral samples

The number of juveniles of A. tenuis sequenced from each of the 9 crosses in 2012 ranged from 2–29 individuals (average ± SE: 11.3 ± 3) (Supplementary Table S1) and a single sample from each parental colony was sequenced concurrently. In 2013, 1–21 A. tenuis juveniles (average ± SE: 8.6 ± 1) were sequenced from each of the 20 families (of the original 25) that survived field deployment (Supplementary Table S2). The adult samples sequenced included three samples per colony from Orpheus parents (from the edges and center of each colony) and one sample per colony for Princess Charlotte Bay parents. For M. digitata, 5–12 eggs per dam were sequenced, along with one sample per maternal colony.

DNA was extracted from juveniles of A.tenuis in 2012 and 2013 with a SDS method82 (additional description in Supplementary Methods). For M. digitata, single egg extractions used the same extraction buffers and bead beating steps as described in ref. 82, although without the subsequent washes and precipitation steps because of the small tissue volumes of single eggs83. Library preparation, sequencing and data analysis were performed separately for 2012 and 2013 samples of A. tenuis and M. digitata, as described in ref. 82. Briefly, the USEARCH pipeline (v. 7)84 and custom-built database of all Symbiodinium-specific NCBI sequences were used to classify reads85, 86, with blast hits above an E-value threshold of 0.001 removed, as they likely represented non-specific amplification of other closely-related species within the Dinoflagellata phylum (Supplementary Table S3). Cleaned reads were clustered with the default 97% identity and minimum cluster size of 2 (thus eliminating all singleton reads), after which all reads were globally aligned to 99% similarity with gaps counted as nucleotide differences.

Symbiodinium databases suggest that hundreds of subclades and types exist within Symbiodinium clades87, 88. These subclades and types likely represent distinct Symbiodinium species89. However, the status of OTUs is less clear; they might represent either unique Symbiodinium genotypes or intragenomic variants10, 17, 18 or both, but they are unlikely to represent distinct Symbiodinium species. Nevertheless, in some cases, OTUs map to known ‘types’ (see ref. 18). Therefore, this OTU-based framework infers delineations between the OTU, subtype, and type levels18, 89. However, a large proportion of OTUs retrieved in this study are unlikely to represent intragenomic variants for two reasons. Firstly, the proportion of intragenomic variants retrieved as OTUs will depend on the methodology used to cluster sequence variants. Clustering across samples at 97% identity greatly diminishes retrieval of intragenomic variants18. Secondly, in contrast to overestimating diversity, clustering across samples at 97% identity also results in an underestimation of relevant biological diversity90. As there is no single-copy marker yet known for Symbiodinium, sequencing additional markers would result in intragenomic challenges similar to those found for ITS-2. Therefore, at this time, sequencing additional markers is not a panacea for dealing with intra-genomic/multicopy variation. Finally, Symbiodinium OTUs listed as “uncultured” were assigned this term based on their Genbank NCBI identifiers, following verbatim the name given by the original depositors of these sequences. Quotes around the term were added to make clear that this is not a functional description or taxonomic designation. Analysis of rarefaction curves suggested that differences in sequencing depth across samples did not affect diversity estimates (additional description in Supplementary Methods).

Data analysis and visualization

Sample metadata were mapped onto circular trait plots using the package ‘diverstree’91. To aid in visualizing the data on the A. tenuis plots, only OTUs that were found within at least three samples were kept, reducing the total OTU count from 422 to 134 for 2012 samples and from 568 to 181 for 2013 samples, giving an overall total of 315 OTUs for A. tenuis. To determine the overlap in Symbiodinium OTUs from A. tenuis data between years that were clustered and mapped separately, the 315 OTUs were aligned in Clustal OMEGA92. OTUs that clustered and blasted to the same accession number (54 of the 315) were deemed to be the same OTU, resulting in a total of 261 distinct OTUs. In total, 80 unique OTUs were found in 2012, 127 were found in 2013, and 54 were shared between years. OTUs with a relative normalized abundance of less than 0.01% were classified as “background”, whilst those with abundances greater than 0.01% were considered “principal”. Rare, background types can play an important role in recovery post-bleaching caused by both low and high temperatures by becoming dominant symbionts50. The cut-off of 0.01% chosen to designate background abundances here is commonly used in microbial, deep sequencing studies examining rare taxa93,94,95, and has been found to fall within the detection limits of deep sequencing for Symbiodinium 17. Furthermore, 0.01% represents approximately 100–200 cells per square cm57, a density of symbionts that has been recognised as ecologically relevant. For example, a survey of four coral species on the GBR revealed clade D populations existed, on average, at levels of 100–10,000 cells per cm2 58. This study is also the first to use deep sequencing to identify Symbiodinium communities in eggs and juveniles of corals, and therefore this lower threshold enabled the inclusion of a greater percentage of Symbiodinium communities with which to explore the diversity present in this life stage. OTUs were further classified by ubiquity across samples, whereby “core” OTUs were defined as those found in >75% of samples, “common” were found in 25–75% of samples, and “rare” were found in <25%. As far fewer OTUs were recovered from M. digitata samples, all 101 OTUs from the one year sampled were used to visualize and classify them by abundance and ubiquity, as described above. Differential abundance testing was performed with ‘DESeq2’, with Benjamini-Hochberg p-adjusted values at 0.0596,97,98. Networks and heatmaps were constructed using un-weighted Unifrac distances of the normalized Symbiodinium abundances in eggs only, where maximum distances were set at 0.4.

Heritability analyses

We estimated the effects of host genotype and maternal environment on variation in Symbiodinium diversity using established quantitative genetic methods5, 31. The extent to which a trait (such as the host’s Symbiodinium community) is genetically regulated can be represented by the degree to which individuals share the same genes31. The degree to which individuals share the same genes can be determined in at least two ways: 1) using information on relatedness through the construction of known pedigrees based on either reproductive crosses (as we have done here), twin data, or known breeding lines; or 2) using genomic marker data (Quantitative Trait Loci)30, 99,100,101. For example, whilst the full genome structure of twins is often not known in heritability studies, twin studies provide subjects of known relatedness (full sibs, half sibs), from which host-genotype sharing can be calculated. Therefore, we have constructed pedigrees of known relatedness using diallel and half-diallel cross designs to construct the degree to which individuals share the same genes (host genotype information). Pedigrees of known relatedness were then combined with host phenotypes for the trait “Symbiodinium community” that had been determined through sequencing. The Symbiodinium community is not a “proxy” for host-phenotype; it is the host-phenotype for symbiosis. In a similar manner, host-phenotypes for symbiosis have been determined in studies of bacterial gut communities in insects and mammals39,40,41. Heritability analysis therefore uses information on variation among samples in both host-genotype (calculated here through relatedness coefficients derived from pedigrees) and host-phenotype (i.e., Symbiodinium community determined through sequencing). We do not explicitly determine which elements of the host genotype regulate the variability in this host trait (Symbiodinium community); such a determination would require Quantitative Trait Loci analysis. Instead, our objective is to quantify the extent to which this trait is genetically regulated.

The Symbiodinium community associated with each adult, juvenile (A. tenuis) or egg (M. digitata) of the two coral species was characterized as a continuous quantitative trait of the host by converting community composition into a single diversity metric. Differences among juveniles in regards to their Symbiodinium communities were examined as a host phenotypic trait. Collapsing complex assemblage data into a single diversity value (local diversity measure)102 was necessary to apply a univariate heritability statistic. Such single diversity metrics have been used to explore the impact of host-genetic variation on bacterial symbiont populations residing within hosts across a range of environments in the adult and infant human body39, 41 as well as in insects40. The Leinster and Cobbold diversity metric (D) incorporates variance-normalized OTU abundances from linear models using negative binomial distributions, OTU sequence diversity, and OTU rarity in the following equation102:

where “q” is a measure of the relative importance of rare species from 0 (very important) to ∞ (not important), and Z is a matrix of genetic similarities of OTUs i through j. Pairwise percent similarities between OTUs sequences were calculated in ‘Ape’ with a “raw” model of molecular evolution, in which the simple proportion of differing nucleotides between pairwise comparisons is calculated and no assumption is made regarding the probability of certain nucleotide changes over others. Finally, P is a matrix of normalized abundances corresponding to each sample and OTU. Incorporating both abundance and diversity of Symbiodinium types into heritability estimates is essential because changes in Symbiodinium community abundance dynamics can change the functional output of the symbiosis as a whole26 and are important in determining coral resilience and bleaching susceptibility25, 103, 104. Model inputs therefore take into account which OTUs were present or absent in each sample, OTU sequence diversity, and the abundance of each OTU.

Heritability estimates for both species presented here represent the initial Symbiodinium community with the time of sampling consistent with complete infection (i.e. defined by the presence of Symbiodinium throughout the polyp) of A. tenuis juveniles (19–22.5 days, personal observation)48, 105. Calculated heritability may vary among traits and throughout ontogeny (i.e. with body size)106 and hence we therefore make no predictions about the heritability of Symbiodinium communities at later ontogenic stages. However, as the early Symbiodinium community can influence juvenile survival82 and because we do not yet know how the earliest communities impact later ones, evaluating the heritability at this initial stage is a logical first step.

Two methods were used to assess heritability. Bayesian methods are powerful tools for assessing heritability of natural (i.e. non-lab, non-model) populations and for non-Gaussian traits (see ref. 5 for a full discussion of the advantages of using Bayesian inference in quantitative genetics). However, parent-offspring regressions were also calculated to facilitate comparisons with previous studies as they make up a majority of estimates available in the literature. The correspondence in heritability estimates between these two methods is well-established (e.g. h2 = 0.51 vs 0.52 for Drosophila melanogaster traits31, 107), although Bayesian MCMC estimates are generally lower5 and confidence intervals around mean estimates generally smaller, especially at low levels of heritability108. Importantly, neither method is dependent on the known relatedness of the parents, but instead rely on relatedness among the juveniles themselves (sib analysis comprised of full and half sibs) or comparisons between juveniles and adult phenotypes (parent-offspring regressions)30.

Regression-based estimates of heritability

Phenotypic values of offspring can be regressed against parental midpoint (average) phenotypic values, with the slope being equal to the narrow-sense heritability of the trait of interest31, 32. Parental midpoint values were calculated by taking the average of dam and sire Symbiodinium diversities for each family and then regressing these values against diversity values for the offspring of each family. Precision of the heritability estimate increases when parents vary substantially in the trait of interest31. Coral colonies dominated by a single or mixed Symbiodinium communities (C, D, C/D communities) can be considered biological extremes and ample evidence describes their contrasting physiological impacts on coral hosts (i.e., growth, bleaching) when associated with D versus C communities in particular26. Therefore, parental colonies selected for breeding were dominated by C1 (families W5, 10) or had mixed communities of C1/D1 (W7), C1/D1/D1a (W11, PCB4, 6, 8, 9), or multiple A, C1 and D types (OI3, 4, 5, 6) (Fig. 2b).

Bayesian linear mixed model estimates of heritability

Heritability estimates were derived from estimates of additive genetic variance calculated from the ‘animal model’, a type of quantitative genetic mixed effects model incorporating fixed and random effects, and relatedness coefficients amongst individuals109. The animal model was implemented using Bayesian statistics with the package ‘MCMCglmm’110. The model incorporated the diversity metric calculated for each juvenile and the pedigree coefficient of relatedness as random effects. Bayesian heritability models were run with 1.5 × 106 iterations, a thinning level of 800 (A. tenuis) or 250 (M. digitata), and a burn-in of 10% of the total iterations. A non-informative flat prior specification was used, following an inverse gamma distribution35. Assumptions of chain mixing, normality of posterior distributions and autocorrelation were met. The posterior heritability was calculated by dividing the model variance attributed to relatedness by the sum of additive and residual variance. The impact of environmental covariance (VEC) was reduced by randomly placing families within the outplant area31. Maternal environmental effects were assessed and were not significant for either A. tenuis or M. digitata based on Deviance Information Criteria (DIC) from Bayesian models35. The influence of different settlement surfaces for A. tenuis juveniles in 2013 was assessed using linear mixed models (fixed effect: substrate, random effect: family) in the ‘nlme’ package111 using the first principal component extracted from PCoA plots and incorporating weighted Unifrac distances of normalized Symbiodinium abundances for juveniles. Model assumptions of homogeneity of variance, normality, and linearity were met. Substrate type did not significantly explain Symbiodinium community differences among samples (LME: F(4) = 1.05, p = 0.38).

Impact of intragenomic variation on heritability analysis

The multicopy nature of Symbiodinium genomes and the presence of intragenomic variants make taxonomic assignments for distinct Symbiodinium sequences difficult, however, advances have been made to name and elucidate the functional diversity within Symbiodinium 112,113,114,115. Single base pair variations in key genetic regions (e.g., intragenomic spacer region-2 ITS-2) can be the sole difference between important taxonomic entities, for example, between a new thermally tolerant C3 type (S. thermophilum) and the ubiquitous C3 type116; which further highlights the need for sensitive methodologies. Whilst different methods have been used to incorporate intragenomic variation into Symbiodinium taxonomy designations (i.e. single cell sequencing117, and pairwise correlations10, 17, 118), the combination of single-cell sequencing, gel-based methods and next generation sequencing suggest that clustering at 97% sequence similarity (the cut-off used here), is sufficient to collapse Symbiodinium from clades A, B and C into type-level designations18.

Even without accounting for intragenomic variation using the 97% clustering threshold, heritability analysis should be impacted little by these pseudo-variants given that intragenomic variants are found within the same genome. These groups of variants would therefore be inherited together and do little to impact variance between individuals of different families (which are important for calculating heritability), causing the bias in a systematic manner. To test this, we employed a three-step approach previously used to classify intragenomic variants82 to the M. digitata dataset. Initial groups of OTUs were chosen from those that clustered closely together on the dendrogram as they have higher per cent similarity relative to other sequences. Correlation coefficients for these groups of closely clustered OTUs were then calculated, and OTUs having highly positive or negative correlations coefficients (−1 to −0.8, 0.8 to 1) were identified as candidate intragenomic variants. To test the impact of accounting for intragenomic variants on Bayesian heritability analysis, MCMC models were then re-run the same way as described above but now incorporating intragenomic variants into the new-derived diversity metric.

Data availability statement

All raw sequencing data will be deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under Accession number SRP077416.

References

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world’s coral reefs. Aust. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 50, 839–866 (1999).

Eakin, C. M., Lough, J. M. & Heron, S. F. In Coral bleaching 41–67 (Springer, 2009).

Glynn, P. W. Coral reef bleaching: ecological perspectives. Coral Reefs 12, 1–17 (1993).

Normile, D. El Niño’s warmth devastating reefs worldwide. Science (80-.). 352, 15–16 (2016).

Charmantier, A., Garant, D. & Kruuk, L. E. B. Quantitative genetics in the wild. (OUP Oxford, 2014).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Climate change, human impacts, and the resilience of coral reefs. Science (80-.). 301, 929–933 (2003).

Brown, B. E., Le Tissier, M. D. A. & Bythell, J. C. Mechanisms of bleaching deduced from histological studies of reef corals sampled during a natural bleaching event. Mar. Biol. 122, 655–663 (1995).

Baird, A. H., Bhagooli, R., Ralph, P. J. & Takahashi, S. Coral bleaching: the role of the host. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 16–20 (2009).

Glynn, P. W., Mate, J. L., Baker, A. C. & Calderon, M. O. Coral bleaching and mortality in Panama and Ecuador during the 1997–1998 El Nino Southern Oscillation event: spatial/temporal patterns and comparisons with the 1982–1983 event. Bull. Mar. Sci. 69, 79–109 (2001).

Kenkel, C. D. et al. Evidence for a host role in thermotolerance divergence between populations of the mustard hill coral (Porites astreoides) from different reef environments. Mol. Ecol. 22, 4335–4348 (2013).

Hawkins, T. D., Krueger, T., Wilkinson, S. P., Fisher, P. L. & Davy, S. K. Antioxidant responses to heat and light stress differ with habitat in a common reef coral. Coral Reefs 34, 1229–1241 (2015).

Krueger, T. et al. Differential coral bleaching—Contrasting the activity and response of enzymatic antioxidants in symbiotic partners under thermal stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 190, 15–25 (2015).

Fellous, S., Duron, O. & Rousset, F. Adaptation due to symbionts and conflicts between heritable agents of biological information. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 663 (2011).

LaJeunesse, T. C. et al. Host–symbiont recombination versus natural selection in the response of coral–dinoflagellate symbioses to environmental disturbance. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 277, 2925–2934 (2010).

Pochon, X., Putnam, H., Burki, F. & Gates, R. Identifying and characterizing alternative molecular markers for the symbiotic and free-living dinoflagellate genus Symbiodinium. PLoS One 7, e29816 (2012).

Baker, A. C. Flexibility and specificity in coral-algal symbiosis: Diversity, ecology, and biogeography of Symbiodinium. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 34, 661–689 (2003).

Quigley, K. M. et al. Deep-sequencing method for quantifying background abundances of Symbiodinium types: exploring the rare Symbiodinium biosphere in reef-building corals. PLoS One 9, e94297 (2014).

Arif, C. et al. Assessing Symbiodinium diversity in scleractinian corals via Next Generation Sequencing based genotyping of the ITS2 rDNA region. Mol. Ecol. 23, 4418–4433 (2014).

Boulotte, N. M. et al. Exploring the Symbiodinium rare biosphere provides evidence for symbiont switching in reef-building corals. ISME J. (2016).

Kenkel, C. D., Setta, S. P. & Matz, M. V. Heritable differences in fitness-related traits among populations of the mustard hill coral, Porites astreoides. Heredity (Edinb). 115, 509–516 (2015).

Fabina, N. S., Putnam, H. M., Franklin, E. C., Stat, M. & Gates, R. D. Symbiotic specificity, association patterns, and function determine community responses to global changes: defining critical research areas for coral Symbiodinium symbioses. Glob. Chang. Biol. 19, 3306–3316 (2013).

Berkelmans, R. & van Oppen, M. J. H. The role of zooxanthellae in the thermal tolerance of corals: a ‘nugget of hope’ for coral reefs in an era of climate change. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 273, 2305–2312 (2006).

Bay, L. K., Doyle, J., Logan, M. & Berkelmans, R. Recovery from bleaching is mediated by threshold densities of background thermo-tolerant symbiont types in a reef-building coral. R. Soc. Open Sci. 3, 1–10 (2016).

Theis, K. R. et al. Getting the hologenome concept right: An eco-evolutionary framework for hosts and their microbiomes. mSystems 1, e00028–16 (2016).

Cunning, R. & Baker, A. C. Not just who, but how many: the importance of partner abundance in reef coral symbioses. Front. Microbiol. 5, 400 (2014).

Cunning, R., Silverstein, R. N. & Baker, A. C. Investigating the causes and consequences of symbiont shuffling in a multi-partner reef coral symbiosis under environmental change. Proc. R. Soc. B 282, 20141725 (2015).

van Oppen, M. J. H., Oliver, J. K., Putnam, H. M. & Gates, R. D. Building coral reef resilience through assisted evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 2307–2313 (2015).

Baird, A. H., Guest, J. R. & Willis, B. L. Systematic and biogeographical patterns in the reproductive biology of scleractinian corals. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 40, 551–571 (2009).

Douglas, A. E. & Werren, J. H. Holes in the hologenome: why host-microbe symbioses are not holobionts. MBio 7, e02099–15 (2016).

Lynch, M. & Walsh, B. Genetics and analysis of quantitative traits (1998).

Falconer, D. S. & Mackay, T. F. C. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics. Longman 19, 1 (1995).

Visscher, P. M., Hill, W. G. & Wray, N. R. Heritability in the genomics era—concepts and misconceptions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 255–266 (2008).

Hedrick, P. W., Coltman, D. W., Festa-Bianchet, M. & Pelletier, F. Not surprisingly, no inheritance of a trait results in no evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, E4810–E4810 (2014).

Houle, D. Comparing evolvability and variability of quantitative traits. Genetics 130, 195–204 (1992).

Wilson, A. J. et al. An ecologist’s guide to the animal model. J. Anim. Ecol. 79, 13–26 (2010).

Franzenburg, S. et al. Distinct antimicrobial peptide expression determines host species-specific bacterial associations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, E3730–E3738 (2013).

Ley, R. E. et al. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science (80-.). 320, 1647–1651 (2008).

Campbell, J. H. et al. Host genetic and environmental effects on mouse intestinal microbiota. ISME J. 6, 2033–2044 (2012).

Benson, A. K. et al. Individuality in gut microbiota composition is a complex polygenic trait shaped by multiple environmental and host genetic factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 18933–18938 (2010).

Parkinson, J. F., Gobin, B. & Hughes, W. O. H. Heritability of symbiont density reveals distinct regulatory mechanisms in a tripartite symbiosis. Ecol. Evol. (2016).

Liu, C. M. et al. Staphylococcus aureus and the ecology of the nasal microbiome. Sci. Adv. 1, e1400216 (2015).

Davy, S. K., Allemand, D. & Weis, V. M. Cell biology of cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 76, 229–261 (2012).

Kuniya, N. et al. Possible involvement of Tachylectin-2-like lectin from Acropora tenuis in the process of Symbiodinium acquisition. Fish. Sci. 81, 473–483 (2015).

Suzuki, G. et al. Early uptake of specific symbionts enhances the post-settlement survival of Acropora corals. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 494, 149–158 (2013).

Yamashita, H., Suzuki, G., Hayashibara, T. & Koike, K. Acropora recruits harbor ‘rare’ Symbiodinium in the environmental pool. Coral Reefs 32, 355–366 (2013).

Gómez-Cabrera, M. et al. Acquisition of symbiotic dinoflagellates (Symbiodinium) by juveniles of the coral Acropora longicyathus. Coral Reefs 27, 219–226 (2008).

Cumbo, V. R., Baird, A. H. & van Oppen, M. J. H. The promiscuous larvae: flexibility in the establishment of symbiosis in corals. Coral Reefs 1–10 (2013).

Abrego, D., van Oppen, M. J. H. & Willis, B. L. Highly infectious symbiont dominates initial uptake in coral juveniles. Mol. Ecol. 18, 3518–3531 (2009).

Nitschke, M. R., Davy, S. K. & Ward, S. Horizontal transmission of Symbiodinium cells between adult and juvenile corals is aided by benthic sediment. Coral Reefs 1–10 (2015).

Silverstein, R. The importance of the rare: the role of background Symbiodinium in the response of reef corals to environmental change (2012).

Jones, A. M., Berkelmans, R., van Oppen, M. J. H., Mieog, J. C. & Sinclair, W. A community change in the algal endosymbionts of a scleractinian coral following a natural bleaching event: field evidence of acclimatization. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 275, 1359–1365 (2008).

LaJeunesse, T. C., Smith, R. T., Finney, J. & Oxenford, H. Outbreak and persistence of opportunistic symbiotic dinoflagellates during the 2005 Caribbean mass coral ‘bleaching’ event. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 276, 4139–4148 (2009).

Lee, M. J. et al. Most low-abundance “background’‘ Symbiodinium spp. are transitory and have minimal functional significance for symbiotic corals. Microb. Ecol. 1–13, doi:10.1007/s00248-015-0724-2 (2016).

Bourne, D. G., Morrow, K. M. & Webster, N. S. Insights into the coral microbiome: underpinning the health and resilience of reef ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 70, 317–340 (2016).

Ainsworth, T. D. et al. The coral core microbiome identifies rare bacterial taxa as ubiquitous endosymbionts. ISME J. 9, 2261–2274 (2015).

Padilla-Gamiño, J. L., Pochon, X., Bird, C., Concepcion, G. T. & Gates, R. D. From parent to gamete: vertical transmission of Symbiodinium (Dinophyceae) ITS2 sequence assemblages in the reef building coral Montipora capitata. PLoS One 7, e38440 (2012).

LaJeunesse, T. C. et al. Specificity and stability in high latitude eastern Pacific coral-algal symbioses. Limnol. Oceanogr. 53, 719–727 (2008).

Mieog, J., van Oppen, M., Cantin, N., Stam, W. & Olsen, J. Real-time PCR reveals a high incidence of Symbiodinium; clade D at low levels in four scleractinian corals across the Great Barrier Reef: implications for symbiont shuffling. Coral Reefs 26, 449–457 (2007).

Oliver, K. M., Smith, A. H. & Russell, J. A. Defensive symbiosis in the real world–advancing ecological studies of heritable, protective bacteria in aphids and beyond. Funct. Ecol. 28, 341–355 (2014).

Moran, N. A., McCutcheon, J. P. & Nakabachi, A. Genomics and evolution of heritable bacterial symbionts. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42, 165–190 (2008).

Vautrin, E. & Vavre, F. Interactions between vertically transmitted symbionts: cooperation or conflict? Trends Microbiol. 17, 95–99 (2009).

Hirose, M. & Hidaka, M. Early development of zooxanthella-containing eggs of the corals Porites cylindrica and Montipora digitata: The endodermal localization of zooxanthellae. Zoolog. Sci. 23, 873–881 (2006).

Ulstrup, K. E., Kuhl, M. & Bourne, D. G. Zooxanthellae harvested by ciliates associated with brown band syndrome of corals remain photosynthetically competent. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 1968–1975 (2007).

Hirose, M., Reimer, J. D., Hidaka, M. & Suda, S. Phylogenetic analyses of potentially free-living Symbiodinium spp. isolated from coral reef sand in Okinawa, Japan. Mar. Biol. 155, 105–112 (2008).

Santos, S. R. Comment on Phylogenetic analysis of free-living strain of Symbiodinium isolate from Jiaozhou Bay, PR China. J. Phycol. 40, 395–397 (2004).

Ritson-Williams, R. et al. New perspectives on ecological mechanisms affecting coral recruitment on reefs. Smithson. Contrib. fo Mar. Sci. 38, 437–457 (2009).

Wolf, J. B. & Wade, M. J. What are maternal effects (and what are they not)? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 364, 1107–1115 (2009).

Weis, V., Reynolds, W., DeBoer, M. & Krupp, D. Host-symbiont specificity during onset of symbiosis between the dinoflagellates Symbiodinium spp. and planula larvae of the scleractinian coral Fungia scutaria. Coral Reefs 20, 301–308 (2001).

Schwarz, J. A., Krupp, D. A. & Weis, V. M. Late larval development and onset of symbiosis in the scleractinian coral Fungia scutaria. Biol. Bull. 196, 70–79 (1999).

Markell, D. A. & Wood-Charlson, E. M. Immunocytochemical evidence that symbiotic algae secrete potential recognition signal molecules in hospite. Mar. Biol. 157, 1105–1111 (2010).

Bay, L. K. et al. Infection dynamics vary between Symbiodinium types and cell surface treatments during establishment of endosymbiosis with coral larvae. Diversity 3, 356–374 (2011).

Fransolet, D., Roberty, S. & Plumier, J.-C. Establishment of endosymbiosis: The case of cnidarians and Symbiodinium. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 420–421, 1–7 (2012).

Mohamed, A. R. et al. The transcriptomic response of the coral Acropora digitifera to a competent Symbiodinium strain: the symbiosome as an arrested early phagosome. Mol. Ecol. (2016).

Schnitzler, C. E. & Weis, V. M. Coral larvae exhibit few measurable transcriptional changes during the onset of coral-dinoflagellate endosymbiosis. Mar. Genomics 3, 107–116 (2010).

Cho, J. The heritable immune system. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 608–609 (2015).

Roederer, M. et al. The genetic architecture of the human immune system: a bioresource for autoimmunity and disease pathogenesis. Cell 161, 387–403 (2015).

Gates, R. D., Hoegh-Guldberg, O., McFall-Ngai, M. J., Bil, K. Y. & Muscatine, L. Free amino acids exhibit anthozoan ‘host factor’ activity: They induce the release of photosynthate from symbiotic dinoflagellates in-vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 92, 7430–7434 (1995).

Lee, S. T. M., Davy, S. K., Tang, S.-L. & Kench, P. S. Mucus sugar content shapes the bacterial community structure in thermally stressed Acropora muricata. Front. Microbiol. 7 (2016).

Hagedorn, M. et al. Trehalose is a chemical attractant in the establishment of coral symbiosis. PLoS One 10, e0117087 (2015).

Lewis, Z. T. et al. Maternal fucosyltransferase 2 status affects the gut bifidobacterial communities of breastfed infants. Microbiome 3, 1 (2015).

Golberg, K., Eltzov, E., Shnit-Orland, M., Marks, R. S. & Kushmaro, A. Characterization of quorum sensing signals in coral-associated bacteria. Microb. Ecol. 61, 783–792 (2011).

Quigley, K. M., Willis, B. L. & Bay, L. K. Maternal effects and Symbiodinium community composition drive differential patterns in juvenile survival in the coral Acropora tenuis. R. Soc. Open Sci. 3, 1–17 (2016).

Gloor, G. B. et al. Type I repressors of P element mobility. Genetics 135, 81–95 (1993).

Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996–998 (2013).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10 (2009).

Tonk, L., Bongaerts, P., Sampayo, E. M. & Hoegh-Guldberg, O. SymbioGBR: a web-based database of Symbiodinium associated with cnidarian hosts on the Great Barrier Reef. BMC Ecol. 13, 7 (2013).

Franklin, E. C., Stat, M., Pochon, X., Putnam, H. M. & Gates, R. D. GeoSymbio: a hybrid, cloud-based web application of global geospatial bioinformatics and ecoinformatics for Symbiodinium-host symbioses. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 12, 369–373 (2012).

Ziegler, M. et al. Biogeography and molecular diversity of coral symbionts in the genus Symbiodinium around the Arabian Peninsula. J. Biogeogr. (2017).

Cunning, R., Gates, R. D. & Edmunds, P. J. Using high-throughput sequencing of ITS2 to describe Symbiodinium metacommunities in St. John, US Virgin Islands. (PeerJ Preprints, 2017).

FitzJohn, R. G. Diversitree: comparative phylogenetic analyses of diversification in R. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 1084–1092 (2012).

Sievers, F. et al. Fast, scalable generation of high‐quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7 (2011).

Galand, P. E., Casamayor, E. O., Kirchman, D. L. & Lovejoy, C. Ecology of the rare microbial biosphere of the Arctic Ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 22427–22432 (2009).

Pedrós-Alió, C. The Rare Bacterial Biosphere. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 4, 449–466 (2012).

Logares, R. et al. Patterns of rare and abundant marine microbial eukaryotes. Curr. Biol. 24, 813–821 (2014).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq.2. Genome Biol. 15, 1–21 (2014).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8, e61217 (2013).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (2012).

Spor, A., Koren, O. & Ley, R. Unravelling the effects of the environment and host genotype on the gut microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 279–290 (2011).

Meyer, E. et al. Genetic variation in responses to a settlement cue and elevated temperature in the reef-building coral Acropora millepora. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 392, 81–92 (2009).

Kenkel, C. D., Traylor, M. R., Wiedenmann, J., Salih, A. & Matz, M. V. Fluorescence of coral larvae predicts their settlement response to crustose coralline algae and reflects stress. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2344 (2011).

Leinster, T. & Cobbold, C. A. Measuring diversity: the importance of species similarity. Ecology 93, 477–489 (2012).

Cunning, R. & Baker, A. C. Excess algal symbionts increase the susceptibility of reef corals to bleaching. Nat. Clim. Chang. (2012).

Cunning, R. et al. Dynamic regulation of partner abundance mediates response of reef coral symbioses to environmental change. Ecology 96, 1411–1420 (2015).

Abrego, D., van Oppen, M. J. H. & Willis, B. L. Onset of algal endosymbiont specificity varies among closely related species of Acropora corals during early ontogeny. Mol. Ecol. 18, 3532–3543 (2009).

Wilson, A. J., Kruuk, L. E. B. & Coltman, D. W. Ontogenetic patterns in heritable variation for body size: using random regression models in a wild ungulate population. Am. Nat. 166, E177–E192 (2005).

Clayton, G. A., Morris, J. A. & Robertson, A. An experimental check on quantitative genetical theory I. Short-term responses to selection. J. Genet. 55, 131–151 (1957).

Villemereuil, P., Gimenez, O. & Doligez, B. Comparing parent–offspring regression with frequentist and Bayesian animal models to estimate heritability in wild populations: a simulation study for Gaussian and binary traits. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4, 260–275 (2013).

Kruuk, L. E. B. Estimating genetic parameters in natural populations using the ‘animal model’. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B Biol. Sci. 359, 873–890 (2004).

Hadfield, J. D. MCMC methods for multi-response generalized linear mixed models: the MCMCglmm R package. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1–22 (2010).

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S. & Sarkar, D. Core Team R. Nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1–118 (2014).

Wham, D., Pettay, D. & LaJeunesse, T. Microsatellite loci for the host-generalist ‘zooxanthella’ & Symbiodinium trenchi and other Clade D. Symbiodinium. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 3, 541–544 (2011).

LaJeunesse, T. C. et al. Ecologically differentiated stress-tolerant endosymbionts in the dinoflagellate genus Symbiodinium (Dinophyceae) Clade D are different species. Phycologia 53, 305–319 (2014).

Parkinson, J. E., Coffroth, M. A. & LaJeunesse, T. C. New species of Clade B Symbiodinium (Dinophyceae) from the greater Caribbean belong to different functional guilds: S. aenigmaticum sp. nov., S. antillogorgium sp. nov., S. endomadracis sp. nov., and S. pseudominutum sp. nov. J. Phycol. 51, 850–858 (2015).

Thornhill, D. J., Lewis, A. M., Wham, D. C. & LaJeunesse, T. C. Host-specialist lineages dominate the adaptive radiation of reef coral endosymbionts. Evolution (N. Y). 68, 352–367 (2014).

Hume, B. C. C. et al. Symbiodinium thermophilum sp. nov., a thermotolerant symbiotic alga prevalent in corals of the world’s hottest sea, the Persian/Arabian Gulf. Sci. Rep. 5, 1–8 (2015).

Wilkinson, S. P., Pontasch, S., Fisher, P. L. & Davy, S. K. The distribution of intra-genomically variable dinoflagellate symbionts at Lord Howe Island, Australia. Coral Reefs 35, 565–576 (2016).

Green, E. A., Davies, S. W., Matz, M. V. & Medina, M. Quantifying cryptic Symbiodinium diversity within Orbicella faveolata and Orbicella franksi at the Flower Garden Banks, Gulf of Mexico. PeerJ 2, e386 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Margaux Hein Mikhail Matz, Marie Strader, Greg Torda, Sarah Davies, Natalie Andrade, Tess Hill and the staff at Orpheus Island Research Station for help with field work and spawning at Orpheus Island. We also thank Dr. Ray Berkelmans and the crew on the RV Ferguson for help with the collection of corals from the northern GBR. All samples of A. tenuis from Wilkie Island and Orpheus Island and M. digitata from Orpheus Island were collected under Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority permits: G12/35236.1, G13/36318.1, and G10/33312.1. Funding was provided by the Australian Research Council through ARC CE1401000020, ARC DP130101421 to B.L.W. and AIMS to L.K.B.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.M.Q., B.L.W. and L.K.B. designed and conducted the experiments, K.M.Q. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript, and all authors made comments on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Quigley, K.M., Willis, B.L. & Bay, L.K. Heritability of the Symbiodinium community in vertically- and horizontally-transmitting broadcast spawning corals. Sci Rep 7, 8219 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08179-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08179-4

This article is cited by

-

Depth distribution and depth adaptation of microbiomes in juvenile and adult scleractinian corals (Pocillopora verrucosa) in the central South China Sea

Coral Reefs (2024)

-

Intraspecific transfer of algal symbionts can occur in photosymbiotic Exaiptasia sea anemones

Symbiosis (2023)

-

The role of gene expression and symbiosis in reef-building coral acquired heat tolerance

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Intrapopulation adaptive variance supports thermal tolerance in a reef-building coral

Communications Biology (2022)

-

Colony self-shading facilitates Symbiodiniaceae cohabitation in a South Pacific coral community

Coral Reefs (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.