Abstract

Angulin proteins are a group of evolutionally conserved type I transmembrane proteins that contain an extracellular Ig-like domain. In mammals, three angulin proteins have been identified, namely immunoglobulin-like domain containing receptor 1 (ILDR1), immunoglobulin-like domain containing receptor 2 (ILDR2), and lipolysis-stimulated lipoprotein receptor (LSR). All three proteins have been shown to localize at tight junctions (TJs) and are important for TJ formation. Mutations in ILDR1 gene have been shown to cause non-syndromic hearing loss (NSHL). In the present work, we show that ILDR1 binds to splicing factors TRA2A, TRA2B, and SRSF1, and translocates into the nuclei when the splicing factors are present. Moreover, ILDR1 affects alternative splicing of Tubulin delta 1 (TUBD1), IQ motif containing B1 (IQCB1), and Protocadherin 19 (Pcdh19). Further investigation show that ILDR2, but not LSR, also binds to the splicing factors and regulates alternative splicing. When endogenous ILDR1 and ILDR2 expression is knockdown with siRNAs in cultured cells, alternative splicing of TUBD1 and IQCB1 is affected. In conclusion, we show here that angulin proteins ILDR1 and ILDR2 are involved in alternative pre-mRNA splicing via binding to splicing factors TRA2A, TRA2B, or SRSF1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Immunoglobulin-like domain containing receptor 1 (ILDR1) is a putative type I transmembrane protein containing an immunoglobulin (Ig)-like extracellular N-terminal domain1. ILDR1 belongs to an evolutionally conserved protein family, angulin protein family, which also includes immunoglobulin-like domain-containing receptor 2 (ILDR2) and lipolysis-stimulated lipoprotein receptor (LSR)2. Mutations of ILDR1 gene are responsible for autosomal recessive hearing impairment DFNB423. Ildr1 knockout mice show profound hearing loss accompanied with postnatal cochlear hair cell degeneration4,5,6. In mouse inner ear, Ildr1 mRNA was detected in hair cells as well as supporting cells, and ILDR1 protein was shown to localize at tricellular tight junctions (tTJs)2, 3. Another tight junction protein, tricellulin, is also required for the structure and function of tTJs, and mutations of tricellulin gene cause autosomal recessive hearing impairment DFNB497. ILDR1 recruits tricellulin to tTJs, whereas DFNB42-associated ILDR1 mutant protein fails to do so2.

Although ILDR1 is suggested to play an important role in regulating the integration of tTJs, it seems that this protein is also involved in functions other than tTJs in the inner ear. Consistent with this hypothesis, hair cell degeneration in Ildr1 knockout mice is more severe than that in tricellulin mutant mice4, 8. Moreover, ILDR1 has been shown to mediate fat-stimulated cholecystokinin (CCK) secretion, raising the possibility that ILDR1 could act as a signaling receptor9. Nevertheless, the role of ILDR1 other than regulating tTJs largely remains unknown at present.

Alternative splicing is important for regulation of protein function and proteomic diversity. During alternative splicing, the exons of pre-mRNAs are spliced together in different arrangements to give rise to distinct mature mRNAs, which ultimately produces structurally and functionally distinct protein variants10. Alternative splicing deficits cause various types of disease including hearing loss11, 12. At present, two splicing factors have been identified to play important roles in the inner ear, namely SRRM4 and SFSWAP13, 14, both of which belong to SR protein family. SR proteins were first discovered in Drosophila when Sfswap, Tra, and Tra-2 were identified as splicing factors through genetic screens15,16,17. All SR proteins contain an arginine/serine-rich region, which was then referred as RS domain. Besides RS domain, typical SR proteins also contain a so-called RNA recognition motif (RRM), which provides RNA-binding specificity. Further studies revealed that SR proteins are phylogenetically conserved and structurally related proteins that are involved in both constitutive and alternative splicing18, 19.

Transformer 2 protein homolog alpha (TRA2A), transformer 2 protein homolog beta (TRA2B), and serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 1 (SRSF1) are also SR protein family members. TRA2A and TRA2B are mammalian homologs of fly Tra-2, and have been shown to play important roles in alternative splicing20, 21. SRSF1, originally named SF2 or ASF, is the first identified mammalian SR protein22, 23. Microarray and RNA sequencing have revealed that Tra2a, Tra2b, and Srsf1 are expressed in the mouse inner ear, though their precise expression pattern and functional role in the inner ear remain elusive24,25,26. In the present work, we show that ILDR1 as well as its paralog ILDR2 could regulate alternative pre-mRNA splicing via binding to TRA2A, TRA2B, and SRSF1.

Results

Identification of TRA2A, TRA2B, and SRSF1 as ILDR1-binding partners

In order to identify ILDR1-binding partners in the inner ear, we performed yeast two-hybrid screening of a chicken cochlear cDNA library using the C-terminal intracellular domain of chicken ILDR1 (228–553 aa) as bait. Among the positive clones identified, several clones encode for a group of splicing factors, including TRA2A, TRA2B, and SRSF1 (Table 1). TRA2A, TRA2B, and SRSF1 belong to SR protein family, which share one or two serine/arginine-rich domain (RS domain) as well as RNA recognition motif (RRM) (Fig. 1A). SR proteins have been shown to play important roles in constitutive as well as alternative pre-mRNA splicing18.

ILDR1 interacts with TRA2A, TRA2B, and SRSF1. (A) Schematic drawing of the domain structures of Mus musculus ILDR1, TRA2A, TRA2B, and SRSF1. (B) Western blots showing that EGFP-tagged TRA2A, TRA2B, and SRSF1 were co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-tagged ILDR1 cytoplasmic fragment. (C) Western blots showing that EGFP-tagged ILDR1 was co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-tagged TRA2A, TRA2B, SRSF1, but not SRSF5. (D) Western blots showing that EGFP-tagged TRA2A RS domain, but not RRM domain, was co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-tagged ILDR1 cytoplasmic fragment. (E) Western blots showing that EGFP-tagged TRA2B RS domain, but not RRM domain, was co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-tagged ILDR1 cytoplasmic fragment. (F) Western blots showing that EGFP-tagged SRSF1 RS domain, but not RRM domain, was co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-tagged ILDR1 cytoplasmic fragment. Expression vectors were transfected into HEK293T cells to express epitope-tagged proteins, and cell lysis were subject to immunoprecipitation. 5% of total protein was loaded as input. IP indicates antibody used for immunoprecipitation and WB indicates antibody used for detection. Uncropped blots are shown in Fig. S9.

We then performed co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments to confirm the interaction between ILDR1 and the splicing factors. ILDR1 is quite conserved in vertebrates. Chicken and mouse ILDR1 share 95% and 60% homology in the extracellular part and the C-terminal end, respectively. In the following work we focus on mouse proteins. The co-IP results showed that EGFP-tagged mouse TRA2A, TRA2B, or SRSF1 is co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-tagged ILDR1 cytoplasmic domain (Fig. 1B). Likewise, EGFP-tagged full-length ILDR1 could be co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-tagged TRA2A, TRA2B, or SRSF1 (Fig. 1C). As a control, another SR protein, SRSF5, was included in the experiment, and the results showed that SRSF5 is not co-immunoprecipitated with ILDR1, confirming the specific interaction between ILDR1 and TRA2A/TRA2B/SRSF1 (Fig. 1C). To further narrow down which domain(s) of TRA2A/TRA2B/SRSF1 is required for the interaction, we performed co-IP experiments with different domains of TRA2A/TRA2B/SRSF1. The results showed that the RS domain is responsible for the interaction with ILDR1 (Fig. 1D–F).

Three ILDR1 splicing transcriptional variants have been identified, namely ILDR1α, ILDR1α, and ILDR1β 1. Full-length ILDR1 (ILDR1α) contains a di-leucine motif and a cysteine-rich region in the cytoplasmic part, and is usually simply referred as ILDR1 for convenience. Compared to ILDR1α, ILDR1α’ misses the di-leucine motif, whereas ILDR1β misses the transmembrane domain as well as the cysteine-rich region (Fig. S1A). Expression of ILDR1α and ILDR1α’, but not ILDR1β, was detected in mouse inner ear by RT-PCR experiment (data not shown). We then amplified the cDNA of ILDR1α’ from mouse inner ear and performed co-IP experiment. The result showed that unlike ILDR1α, ILDR1α’ cytoplasmic domain was not co-immunoprecipitated with TRA2B, suggesting that the di-leucine motif is necessary for the interaction between ILDR1 and the splicing factors (Fig. S1B).

ILDR1 translocates into the nuclei when TRA2A, TRA2B, or SRSF1 is present

Exogenous ILDR1 has been shown to localize in the cytoplasm of HEK293T cells1. Consistently, we found that ILDR1-GFP mainly localizes in the cytoplasm in COS-7 cells (Fig. 2A). In contrast, TRA2A-mCherry, TRA2B-mCherry, and SRSF1-mCherry localize exclusively in the nuclei (Fig. 2B–D). Interestingly, when cotransfected together with TRA2A-mCherry, TRA2B-mCherry, or SRSF1-mCherry, ILDR1-GFP translocates from the cytoplasm into the nuclei (Fig. 2E–G, Fig. S2). The recruitment of ILDR1 into the nuclei by these splicing factors suggests that ILDR1 might play a role in splicing regulation. Noticeably, ILDR1α’-GFP does not move into the nuclei when TRA2A/TRA2B/SRSF1 is present (Fig. S1C–F), consistent with the finding that ILDR1α’ does not interact with these splicing factors (Fig. S1B).

ILDR1 translocates into the nuclei when TRA2A, TRA2B, or SRSF1 is present. (A) ILDR1-GFP localizes in the cytoplasm. (B–D) TRA2A-mCherry, TRA2B-mCherry, and SRSF1-mCherry localize in the nuclei. (E–G) When cotransfected, ILDR1-GFP moves into the nuclei, colocalizing with TRA2A-mCherry, TRA2B-mCherry, or SRSF1-mCherry. Expression vectors were transfected into COS-7 cells to express epitope-tagged proteins. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 20 μm.

Tra2a, Tra2b, and Srsf1 are expressed in the mouse inner ear

Transcriptome analysis has suggested that Tra2a, Tra2b, and Srsf1 are expressed in the mouse inner ear (SHIELD; https://shield.hms.harvard.edu)25, 26. To examine their expression pattern in the cochlea, in situ hybridization was performed using whole-mount mouse cochlea. The results showed that Tra2a, Tra2b, and Srsf1 are expressed in both hair cells and supporting cells. A strong expression of Tra2b in the spiral ganglion cells was also observed (Fig. S3).

ILDR1 affects alternative pre-mRNA splicing

Genome-wide analysis has revealed that TRA2A/TRA2B/SRSF1 is involved in the splicing of many alternative exons27,28,29. We picked Tubulin delta 1 (Tubd1), IQ motif containing B1 (Iqcb1), and Protocadherin 19 (Pcdh19) as target genes to examine whether ILDR1 could affect TRA2A/TRA2B/SRSF1-mediated alternative splicing. These three genes were chosen because their alternative splicing could be readily detected in our hands. HEK293T cells were transfected with expression vectors for TRA2B (or SRSF1) with or without ILDR1, and RT-PCR results showed that TRA2B and SRSF1 promote the inclusion of exon 4 of TUBD1 and exon 12 of IQCB1, respectively, whereas ILDR1 antagonizes the function of TRA2B/SRSF1 (Fig. 3A and B). As for Pcdh19, HEK293T cells were transfected with expression vectors for SRSF1 with or without ILDR1 alongside a minigene consisting of exon 2 and flanking exons/introns of mouse Pcdh19 gene. RT-PCR-based evaluation of pre-mRNA splicing demonstrated that SRSF1 promotes the inclusion of Pcdh19 exon 2, whereas ILDR1 antagonizes the function of SRSF1 (Fig. S4A). Taken together, our data suggest that ILDR1 regulates SRSF1- and TRA2B-meidated alternative pre-mRNA splicing.

TUBD1 and IQCB1 pre-mRNA splicing is affected by ILDR1. (A) RT-PCR revealed that exon 4 of endogenous TUBD1 in HEK293T cells is subjected to alternative splicing (lane 1). The inclusion of exon 4 is enhanced by TRA2B (lane 2), whose effect is inhibited when ILDR1 is present (lane 3). (B) RT-PCR revealed that exon 12 of endogenous IQCB1 in HEK293T cell is subjected to alternative splicing (lane 1). The inclusion of exon 12 is enhanced by SRSF1 (lane 2), whose effect is inhibited when ILDR1 is present (lane 3). (C) The alternative splicing of Tubd1 exon 4 was not affected in Ildr1 knockout mice. (D) The alternative splicing of Iqcb1 exon 12 was not affected in Ildr1 knockout mice. The relative exon inclusion rate was calculated from three independently performed experiments. The differences between groups were determined by Student’s t-test. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

We then used Ildr1 knockout mice to examine whether loss of ILDR1 affects alternative pre-mRNA splicing in the inner ear. Total RNA were extracted from the cochlea of P0 wildtype and Ildr1 knockout mice, and RT-PCR was performed to examine the alternative splicing of Tubd1, Iqcb1, and Pcdh19 genes. Unexpectedly, no difference was observed between wildtype and Ildr1 knockout mice (Fig. 3C and D, Fig. S4B). To further examine whether loss of ILDR1 affects alternative splicing, RNA from P0 cochlea of wildtype and Ildr1 knockout mice were subjected to RNA-seq analysis, which did not reveal any significant differences in alternative gene splicing (data not shown). To verify the RNA-seq result, twenty-four genes that might show different splicing patterns according to RNA-seq result were picked and their alternative splicing in wildtype and Ildr1 knockout mice was examined by RT-PCR. The results showed that the splicing of these genes is indeed not affected by ILDR1 deficiency (Fig. S5).

Ildr2 is upregulated in the inner ear of Ildr1 knockout mice

The fact that alternative splicing is not affected by loss of ILDR1 prompted us to look for possible explanation. It has been shown that sometimes loss of a particular protein could be compensated for by its homologous protein. As mentioned above, ILDR1 belongs to evolutionally conserved angulin protein family, which includes ILDR1, ILDR2, and LSR. We then examined the expression of Ildr2 and Lsr in Ildr1 knockout mouse. RT-PCR and quantitative real-time PCR showed that expression of Ildr2 is greatly increased in the basilar membrane of Ildr1 knockout mice compared with wildtype mice (Fig. 4A and B). However, the expression of Lsr was not obviously affected by Ildr1 deficiency (Fig. 4A and B). Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed to examine the expression pattern of Ildr2 and Lsr in the mouse cochlea. The results showed that Ildr2 and Lsr are expressed in both hair cells and supporting cells (Fig. S6). In situ hybridization results also confirmed that Ildr2, but not Lsr, is upregulated in the cochlea in Ildr1 knockout mice (Fig. 4C–D’).

Ildr2 is upregulated in Ildr1 knockout mice. (A) RT-PCR revealed that Ildr2, but not Lsr, is upregulated in Ildr1 knockout mice. β-actin was included as internal control. (B) Quantitative real-time PCR revealed that Ildr2, but not Lsr, is upregulated in Ildr1 knockout mice. The differences between groups were determined by Student’s t-test. **P < 0.01. (C–D’) In situ hybridization showed that Ildr2 and Lsr are expressed in mouse cochlea, and Ildr2 expression is upregulated in Ildr1 knockout mice. Scale bar: 15 μm.

ILDR2 binds TRA2A/TRA2B/SRSF1

We then performed experiments to examine the possibility that ILDR2 and/or LSR might regulate alternative splicing and compensate for loss of ILDR1. The three angulin proteins have similar domain architecture and share high homology between each other (Fig. 5A). First, we examined whether ILDR2 and LSR interact with TRA2A/TRA2B/SRSF1 by performing co-IP experiments. The results showed that both ILDR2 and LSR could be co-IPed together with TRA2A/TRA2B/SRSF1 (Fig. 5B–D).

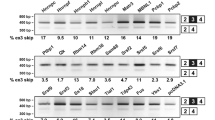

ILDR2 binds TRA2A/TRA2B/SRSF1. (A) Schematic drawing of the domain structures of Mus musculus ILDR1, ILDR2, and LSR. The identity and similarity between each other were indicated below. (B) Western blots showing that EGFP-tagged TRA2A was co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-tagged cytoplasmic fragment of ILDR1, ILDR2, or LSR. (C) Western blots showing that EGFP-tagged TRA2B was co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-tagged cytoplasmic fragment of ILDR1, ILDR2, or LSR. (D) Western blots showing that EGFP-tagged SRSF1 was co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-tagged cytoplasmic fragment of ILDR1, ILDR2, or LSR. Expression vectors were transfected into HEK293T cells to express epitope-tagged proteins, and cell lysis were subject to immunoprecipitation. 5% of total protein was loaded as input. IP indicates antibody used for immunoprecipitation and WB indicates antibody used for detection. Uncropped blots are shown in Fig. S10. ILDR2-GFP (E) and LSR-GFP (G) localize in the cytoplasm. However, when TRA2B-mCherry is present, ILDR2-GFP (F) but not LSR-GFP (H) translocates into the nuclei. Expression vectors were transfected into COS-7 cells to express epitope-tagged proteins. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Next, we examined the subcellular localization of ILDR2 and LSR in cultured cells. Similar to ILDR1, when expressed alone in cultured COS-7 cells, GFP-tagged ILDR2 and LSR localize in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5E and G). When mCherry-tagged TRA2B is present, ILDR2 translocates into the nuclei and colocalizes with TRA2B, whereas LSR still remains in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5F and H). This result suggest that although all three angulin proteins could bind the splicing factors in vitro, only ILDR1 and ILDR2, but not LSR, colocalize with the splicing factor in the nuclei in cultured cells.

ILDR2 affects alternative pre-mRNA splicing

TUBD1, IQCB1, and Pcdh19 genes were used as target genes to examine whether ILDR2 and/or LSR could affect alternative splicing. RT-PCR-based evaluation of pre-mRNA splicing demonstrated that, similar to ILDR1, ILDR2 inhibits SRSF1- or TRA2B-mediated alternative splicing, whereas LSR does not (Fig. 6A and B, Fig. S7). Taken together, given the fact that Ildr2 is upregulated in Idlr1 knockout mice and that ILDR2 can regulate alternative splicing as ILDR1 does, we hypothesize that ILDR2 might compensate for the loss of ILDR1 in splicing regulation.

ILDR2 affects TUBD1 and IQCB1 pre-mRNA splicing. (A) RT-PCR revealed that exon 4 of endogenous TUBD1 in HEK293T cells is subjected to alternative splicing (lane 1). The inclusion of exon 4 was enhanced by TRA2B (lane 2), whose effect was inhibited by ILDR1 (lane 3) or ILDR2 (lane 4), but not LSR (lane 5). The level of overexpression was examined via RT-PCR and Western blot. (B) RT-PCR revealed that exon 12 of endogenous IQCB1 in HEK293T cells is subjected to alternative splicing (lane 1). The inclusion of exon 12 was enhanced by SRSF1 (lane 2), whose effect was inhibited by ILDR1 (lane 3) or ILDR2 (lane 4), but not LSR (lane 5). The level of overexpression was examined via RT-PCR and Western blot. (C) RT-PCR revealed that the inclusion of exon 4 of TUBD1 in HEK293T cells was enhanced when ILDR1 and/or IDLR2 were knockdown. (D) RT-PCR revealed that the inclusion of exon 12 of IQCB1 in HEK293T cells was enhanced when ILDR1 and/or IDLR2 were knockdown. The relative exon inclusion rate was calculated from three independently performed experiments. The differences between groups were determined by Student’s t-test. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant.

To further test this hypothesis, we knockdown the expression of endogenous ILDR1 and/or ILDR2 in cultured cells and examined its effect on alternative splicing. Transiently-transfected siRNA downregulates the expression of ILDR1 or ILDR2 specifically in HEK293T cells without affecting each other (Fig. S8A and B). This is in sharp contrast to what happens in Ildr1 knockout mice. As a result, alternative splicing of TUBD1 and IQCB1 was affected in ILDR1 or ILDR2 knockdown cells (Fig. 6C and D). When the expression of both ILDR1 and ILDR2 was downregulated simultaneously with siRNAs, alternative splicing of TUBD1 and IQCB1 was affected to a greater extent (Fig. 6C and D, Fig. S8C and D). This result strongly supports the role of ILDR1/2 proteins in splicing regulation.

Discussion

Angulin proteins are evolutionally conserved type I transmembrane proteins containing an extracellular Ig-like domain. At present three mammalian angulin proteins have been identified, namely LSR, ILDR1, and ILDR2, which are also known as angulin-1, angulin-2, and angulin-3, respectively2. All three angulin proteins have been shown to localize at tight junctions (TJs) and could recruit tricellulin, another important TJ component2, 30. In the present work we demonstrate that besides TJs regulation, angulin proteins are also involved in alternative pre-mRNA splicing through binding to specific splicing factors.

Our data show that when expressed in cultured cells, ILDR1 and ILDR2 bind to splicing factors TRA2A, TRA2B, or SRSF1, and translocate into the nuclei. Several lines of evidence suggest that the interaction and translocation are not caused by the overexpression of tagged proteins. First, SR family splicing factor SRSF5 was included in the co-IP experiment as a negative control, and the result showed that SRSF5 is not co-IPed with ILDR1 as TRA2A, TRA2B, or SRSF1 does. Presumably the interaction of RS domain with ILDR1 requires specific amino acids context that does not exist in SRSF5. Second, ILDR1α’ is an ILDR1 variant that only misses a di-leucine motif compared to the full length ILDR1. However, ILDR1α’ does not bind to TRA2A, TRA2B, or SRSF1, and does not translocate to the nuclei when the splicing factors are present. This result suggests that the di-leucine motif is necessary for the interaction. Third, LSR is an angulin protein family member and is homologous to ILDR1 and ILDR2. Although LSR is co-IPed with the splicing factors in vitro, it does not translocate into the nuclei when the splicing factors are present. Taken together, we believe that the interaction between ILDR1/ILDR2 and the splicing factors is specific.

It has been shown that transmembrane proteins such as receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) and Notch receptor can translocate into the nuclei after cleavage by proteases. Through sequential cleavage by multiple proteases, a soluble cytoplasmic domain is released and translocates into the nuclei31, 32. We examined the molecular weight of ILDR1, ILDR2 and LSR by performing western blot, and found that ILDR1/ILDR2/LSR is not cleaved into smaller fragment when the splicing factors (SRSF1, TRA2A, or TRA2B) are present. This result suggests that the translocation of ILDR1 and ILDR2 into the nuclei is not mediated by protease cleavage.

Another hypothetical explanation suggests that after activation by ligands, the full-length transmembrane proteins are delivered from the cell surface to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), then extracted into the cytoplasm and finally translocated into the nuclei, although the detailed mechanism remains elusive31. Interestingly, our group and others show that when heterogeneously expressed in cultured cells, ILDR1, ILDR2 or LSR mainly localizes in the cytoplasm with an ER-like pattern1. In fact, exogenous ILDR2 has been shown to primarily locate in the ER of cultured hepatoma and neuronal cells33. In this scenario, the splicing factors might participate in the shuttling of ILDR1/ILDR2 into the nuclei through binding to them. Further investigation is needed to fully understand the detailed mechanism.

Our data show that the interaction with angulin proteins requires the RS domain of TRA2A/TRA2B/SRSF1. RS domain is involved in protein-protein interactions that facilitate recruitment of the spliceosome34, 35, or directly contact the pre-mRNA to promote spliceosome assembly36, 37. RS domain was also suggested to act as a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and regulate the nuclear localization of SR proteins through binding to transpotin-SR38, 39. Here we show that the interaction of the RS domain with angulin proteins does not affect the nuclear localization of TRA2A/TRA2B/SRSF1. Nevertheless, interaction with the RS domain interferes with TRA2A/TRA2B/SRSF1-mediated alternative splicing through a yet unknown mechanism.

We do not observe any changes in alternative splicing in Ildr1 knockout mice. There has been evidence suggesting that angulin proteins could compensate for the loss of each other. For example, in Ildr1 knockout mice, compensatory TJ localization of LSR was observed in the organ of Corti, which is believed to be responsible for recruiting tricellulin to TJs in the absence of ILDR15. In the present work, we found that Ildr2 expression is upregulated in the inner ear of Ildr1 knockout mice, and might compensate for ILDR1 deficiency in alternative splicing regulation. Consistently, alternative splicing is affected when endogenous ILDR1 and ILDR2 expression is knockdown in cultured cells, strongly supporting the role of ILDR1/2 proteins in splicing regulation.

In the present work, we show that ILDR1/ILDR2 could regulate the alternative splicing of TUBD1, IQCB1, and Pcdh19. TUBD1 encodes delta-tubulin that is associated with the centrioles40. In testis, delta-tubulin localizes at the manchette in the sperm head as well as along the principal piece of sperm flagellum, and is involved in sperm maturation41, 42. IQCB1 encodes an IQ domain-containing protein nephrocystin 5, and mutation of IQCB1 gene is the most frequent cause of the renal-retinal Senior-Loken syndrome (SLSN)43. IQCB1 localizes to the primary cilia of renal epithelial cells and connecting cilia of photoreceptor cells, and is required for the trafficking of membrane cargos to the cilia44. PCDH19 encodes a delta-protocadherin, and mutations of PCDH19 are associated with epilepsy and mental retardation45,46,47. Transcriptome analysis suggested that Tubd1, Iqcb1, and Pcdh19 are expressed in the mouse inner ear (SHIELD; https://shield.hms.harvard.edu)25, 26, whereas their exact roles in hearing remain elusive. Further investigation is also needed to identify more target genes other than TUBD1, IQCB1, and Pcdh19 whose alternative splicing is regulated by ILDR1/2.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Generation and characterization of Ildr1 knockout mice have been described previously6. All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong University and conducted accordingly. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Plasmid construction

The cDNA encoding the cytoplasmic part of chicken ILDR1 (amino acids 228–553) was cloned into vector pBD-GAL4 Cam (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) to express the bait protein for yeast two-hybrid screening. The coding sequences of mouse Ildr1, Ildr2, and Lsr were cloned into pEGFP-N2. The coding sequences of mouse Tra2a, Tra2b, Srsf1, and Srsf5 were cloned into pmCherry-N1, pEGFP-C2, and pMyc-C2 (modified pEGFP-C2 with EGFP-coding sequence replaced by Myc-coding sequence). The cDNA encoding the cytoplasmic part of mouse ILDR1, ILDR2, and LSR were cloned into pMyc-C2. The cDNA encoding the RS and RRM domains of mouse TRA2A, TRA2B, and SRSF1 were cloned into pEGFP-C2. Mouse Pcdh19 minigene was amplified from mouse genomic DNA and cloned into pcDNA3.1(+). All the constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing.

Yeast two-hybrid screening

Yeast two-hybrid screening was performed as described previously48, 49. Briefly, yeast strain AH109 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) was sequentially transformed with the bait plasmid and a chicken cochlear cDNA library in HybriZAP pAD-GAL4 vector50. HIS3 was used as the reporter gene for the screening in presence of 2.5 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT). Positive colonies were further tested for activation of two other reporter genes, ADE2 and lacZ. Then the pAD-GAL4 prey vectors in triple-positive colonies were recovered, and cDNA inserts were determined by Sanger sequencing.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from mouse tissues or cells transfected with expression vectors using TRIzol reagent (Ambion, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription (RT) was carried out using a cDNA synthesis kit (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Dalian, China). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using this cDNA as template with the following primers: Ildr1 forward primer, CCGGCGGCTGATGAAGAAAGACTC, reverse primer, AGGGCAGCAACAGCGGGTAGGA (706 bp); Ildr2 forward primer, GGGCTGCTTGCTGATCTCTT, reverse primer, CAAAGTTCTTCCGCGACAGC (745 bp); Lsr forward primer, GCTATGTCAGATGTCCCTGCT, reverse primer, GTCATAGAGGTCATCCCGGC (725 bp); Tra2b forward primer, TTCCCGAAGTGGAAGTGCTC, reverse primer, CCTGCGATAATCTCGGCTGT (226 bp); Srsf1 forward primer, GGACCGCCCTTCGCCTTCGTT, reverse primer, ACTCTGTTCTCGGACCGCCTGGAC (212 bp); β-actin forward primer, ACGGCCAGGTCATCACTATTG, reverse primer, AGGGGCCGGACTCATCGTA (372 bp). To achieve the best possible sensitivity and specificity, cycle lengths for different PCR reaction sets were adjusted between 24 and 36 cycles, and annealing temperatures were adjusted between 55 and 62 °C. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on agarose gel.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out using SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM system (Perfect Real Time, Takara). The primers and template were the same as that used in RT-PCR. Amplification and detection were run in a Roche 480 Sequence Detection System with an initial cycle of 95 °C for 10 s followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 62 °C for 10 s and 72 °C for 5 s. All PCR reactions were performed in triplicate.

Cell culture, transfection and immunofluorescence assay

Cultured cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and transfected with expression vectors or siRNAs using jetPRIME transfection agent (Polyplus Transfection Inc., New York, NY, USA, Cat. No. PT-114–15) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To visualize the localization of GFP- or mCherry-tagged proteins, transfected COS-7 cells that grown on glass coverslips were fixed with 4% PFA, then incubated with DAPI (Gen-View Scientific Inc., El Monte, CA, USA). Slides were mounted in mounting solution (50% glycerol/PBS) and imaged using a confocal microscope (LSM 700, Zeiss, Germany).

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) and western blot

HEK293T cells were transfected with expression vectors as described above, then washed twice with PBS 24 hours after transfection and resuspended in ice-cold lysis buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris at pH 7.5, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, and 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). After centrifuging at 4 °C for 20 minutes, the supernatant was collected and incubated with immobilized anti-Myc antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, Cat. No. E6654) at 4 °C overnight. Immunoprecipitated proteins were washed three times with 500 mM lysis buffer and then analyzed by western blot. Protein samples were resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE, then transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). After blocking in PBS containing 5% BSA and 0.1% Tween-20, the membrane was incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-Myc antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. M4439, 1:5000 diluted) or mouse monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (Abmart, Shanghai, China, Cat. No. M20004, 1:5000 diluted) at 4 °C over night, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA, Cat. No. 170–6516) at 4 °C for an hour. The signals were detected with the ECL system (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA).

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Templates for probe transcription were amplified by PCR and cloned into pBS(-) vector. The PCR primer sequences were as below (EcoR I and Sal I restriction sites are underlined): Ildr2 forward primer, 5′-AATGAATTCGGAGAATCCTTGGGC-3′, reverse primer, 5′-ATTGTCGACGTACCCGGCCTTGGC-3′ (540 bp); Lsr forward primer, 5′-AATGAATTCCGCCGGCGGCCAGCG-3′, reverse primer 5′-ATTGTCGACCTGCGTACGCCTCGT-3′, (540 bp); Tra2a forward primer, 5′-AATGAATTCATGAGTGATGTAGAGGAG-3′, reverse primer 5′-ATTGTCGACTCAATAGCGTCTTGGACT-3′, (849 bp); Tra2b forward primer, 5′-AATGAATTCATGAGCGACAGCGGCGAG-3′, reverse primer 5′-ATTGTCGACTTAGTAGCGACGAGGTGA-3′, (867 bp); Srsf1 forward primer, 5′-AATGAATTCATGTCGGGAGGTGGTGTG-3′, reverse primer 5′-ATTGTCGACTTAAGAAAACTGTATCCA-3′, (606 bp). The vectors were then linearized with Not I or Xho I, and antisense or sense probes were transcribed using T7 or T3 RNA polymerase and labeled with digoxigenin-11-UTP (Roche). Cochleae of P8 mice were dissected out and fixed with 4% PFA. The tissues were treated with 1 mg/ml proteinase K for 15 min, then incubated overnight at 60 °C with digoxigenin-labeled probes in hybridization solution containing 50% (v/v) formamide, 5 × saline sodium citrate, 1 mg/ml yeast RNA and 100 μg/ml heparin, followed by incubation overnight with anti-digoxigenin antibody (Roche). Signals were developed in NBT/BCIP Stock Solution (Roche) and cochleae were mounted in mounting solution (50% glycerol/PBS) and imaged with a Nikon Eclipse 800 microscope using differential interference contrast microscopy.

RNA-seq

RNA-seq was carried out by Genesky Biotechnologies Inc, Shanghai, China. Briefly, the basilar membranes were collected from postnatal day 0 (P0) wild type or Ildr1 -/- mice, and the RNA sequencing libraries were constructed from the extracted and amplified RNA using the standard Illumina library preparation protocols. RNA-seq was performed on Illumina HiSeq. 2000 platform using 100 bp PE protocol. Raw sequencing reads were evaluated by FastQC, then trimmed by trim_galore to remove the primers and low-quality (Q < 10) sequences. Cleaned reads were aligned to GRCm38/mm10 mouse genome assembly using Tophat with at most 2 mismatches. Alternative splicing (AS) events of samples were extracted and compared using the tool ASprofile51.

Target gene splicing examination

HEK293T cells were transfected with the corresponding expression plasmids or siRNAs (Sigma-Aldrich, si-ildr1-1: SASI_Hs01_00025907; si-ildr1-2: SASI_Hs01_00025910; si-ildr2-1: SASI_Hs01_00228126; si-ildr2-2: SASI_Hs01_00228127). The efficiency of knockdown was examined by quantitative PCR with ILDR1 forward primer 5′-CGATGTCCCCTCATCCAGTG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GCCTCTCCACACTCCCTTTTT-3′; ILDR2 forward primer 5′-TGTTCGCAAAGGTTACCGGA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GCCTGAAGCTCTCTCGATCC-3′. The splicing efficiency of human TUBD1 exon 4 was evaluated by performing RT-PCR with forward primer 5′-GGTTCTGGAAACAACTGGGC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AGCTGATGTGCGAGGACTTG-3′. The splicing efficiency of human IQCB1 exon 12 was evaluated by performing RT-PCR with forward primer 5′-GCTTCCATCTGCTGTGATTGC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GAGTTCTTGGAGTCCTCGCC-3′. Splicing of mouse Tubd1 exon 4 in wild-type or Ildr1 knockout mice was evaluated by performing RT-PCR with forward primer 5′-GATCTGGGAACAACTGGGCA-3′ and reverse primer 5′- GTAGGCTGGAACACACTCCC-3′. Splicing of mouse Iqcb1 exon 12 in wild-type or Ildr1 knockout mice was evaluated by performing RT-PCR with the same primers used for human IQCB1. Primer sequences for examination of other genes’ splicing are listed in Table S1.

Mouse Protocadherin 19 (Pcdh19) genomic sequence spanning exon 1 through 3 was PCR amplified from mouse inner ear genomic DNA using forward primer 5′-TGGAAGCTTTCCATTGCGGGCATTCTCTT-3′ containing a flanking Hind III restriction site (underlined) and reverse primer 5′-ATTGGTACCGGGAGGAGCAACTGACAACA-3′ containing a flanking Kpn I restriction site (underlined). This fragment was cloned into pcDNA3.1(+) to construct the reporter minigene plasmid, which was then used for transfection into HEK293T cells together with other expression plasmids. The splicing efficiency of Pcdh19 minigene was evaluated by performing RT-PCR with forward primer 5′-TGGCAATCAAATGCAAGCGT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-ATGCCCATAGGAGTACTCAGC-3′.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as means ± SD from at least 3 independent experiments. The differences between groups were determined by Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

References

Hauge, H., Patzke, S., Delabie, J. & Aasheim, H. C. Characterization of a novel immunoglobulin-like domain containing receptor. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 323, 970–978, doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.188 (2004).

Higashi, T. et al. Analysis of the ‘angulin’ proteins LSR, ILDR1 and ILDR2–tricellulin recruitment, epithelial barrier function and implication in deafness pathogenesis. Journal of Cell Science 126, 966–977, doi:10.1242/jcs.116442 (2013).

Borck, G. et al. Loss-of-function mutations of ILDR1 cause autosomal-recessive hearing impairment DFNB42. American Journal of Human Genetics 88, 127–137, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.12.011 (2011).

Morozko, E. L. et al. ILDR1 null mice, a model of human deafness DFNB42, show structural aberrations of tricellular tight junctions and degeneration of auditory hair cells. Human Molecular Genetics 24, 609–624, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddu474 (2015).

Higashi, T., Katsuno, T., Kitajiri, S. & Furuse, M. Deficiency of Angulin-2/ILDR1, a tricellular tight junction-associated membrane protein, causes deafness with cochlear hair cell degeneration in mice. PLoS One 10, e0120674, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0120674 (2015).

Sang, Q. et al. ILDR1 deficiency causes degeneration of cochlear outer hair cells and disrupts the structure of the organ of Corti: a mouse model for human DFNB42. Biology Open 4, 411–418, doi:10.1242/bio.201410876 (2015).

Riazuddin, S. et al. Tricellulin is a tight-junction protein necessary for hearing. American Journal of Human Genetics 79, 1040–1051, doi:10.1086/510022 (2006).

Nayak, G. et al. Tricellulin deficiency affects tight junction architecture and cochlear hair cells. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 123, 4036–4049, doi:10.1172/JCI69031 (2013).

Chandra, R. et al. Immunoglobulin-like domain containing receptor 1 mediates fat-stimulated cholecystokinin secretion. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 123, 3343–3352, doi:10.1172/JCI68587 (2013).

Blencowe, B. J. Alternative splicing: new insights from global analyses. Cell 126, 37–47, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.023 (2006).

Ben Rebeh, I. et al. Reinforcement of a minor alternative splicing event in MYO7A due to a missense mutation results in a mild form of retinopathy and deafness. Molecular Vision 16, 1898–1906 (2010).

Wang, Y., Liu, Y., Nie, H., Ma, X. & Xu, Z. Alternative splicing of inner-ear-expressed genes. Frontiers of Medicine 10(3), 250–257, doi:10.1007/s11684-016-0454-y (2016).

Nakano, Y. et al. A mutation in the Srrm4 gene causes alternative splicing defects and deafness in the Bronx waltzer mouse. PLoS Genetics 8, e1002966, doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002966 (2012).

Moayedi, Y. et al. The candidate splicing factor Sfswap regulates growth and patterning of inner ear sensory organs. PLoS Genetics 10, e1004055, doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004055 (2014).

Chou, T. B., Zachar, Z. & Bingham, P. M. Developmental expression of a regulatory gene is programmed at the level of splicing. The EMBO Journal 6, 4095–4104 (1987).

Boggs, R. T., Gregor, P., Idriss, S., Belote, J. M. & McKeown, M. Regulation of sexual differentiation in D. melanogaster via alternative splicing of RNA from the transformer gene. Cell 50, 739–747 (1987).

Amrein, H., Gorman, M. & Nothiger, R. The sex-determining gene tra-2 of Drosophila encodes a putative RNA binding protein. Cell 55, 1025–1035 (1988).

Long, J. C. & Caceres, J. F. The SR protein family of splicing factors: master regulators of gene expression. The Biochemical Journal 417, 15–27, doi:10.1042/BJ20081501 (2009).

Anko, M. L. Regulation of gene expression programmes by serine-arginine rich splicing factors. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 32, 11–21, doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.03.011 (2014).

Dauwalder, B., Amaya-Manzanares, F. & Mattox, W. A human homologue of the Drosophila sex determination factor transformer-2 has conserved splicing regulatory functions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93, 9004–9009 (1996).

Tacke, R., Tohyama, M., Ogawa, S. & Manley, J. L. Human Tra2 proteins are sequence-specific activators of pre-mRNA splicing. Cell 93, 139–148 (1998).

Ge, H. & Manley, J. L. A protein factor, ASF, controls cell-specific alternative splicing of SV40 early pre-mRNA in vitro. Cell 62, 25–34 (1990).

Krainer, A. R., Conway, G. C. & Kozak, D. Purification and characterization of pre-mRNA splicing factor SF2 from HeLa cells. Genes & Development 4, 1158–1171 (1990).

Miranda-Rottmann, S., Kozlov, A. S. & Hudspeth, A. J. Highly specific alternative splicing of transcripts encoding BK channels in the chicken’s cochlea is a minor determinant of the tonotopic gradient. Molecular and Cellular Biology 30, 3646–3660, doi:10.1128/MCB.00073-10 (2010).

Scheffer, D. I., Shen, J., Corey, D. P. & Chen, Z. Y. Gene expression by mouse inner ear hair cells during development. The Journal of Neuroscience 35, 6366–6380, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5126-14.2015 (2015).

Shen, J., Scheffer, D. I., Kwan, K. Y. & Corey, D. P. SHIELD: an integrative gene expression database for inner ear research. Database (Oxford) 2015, bav071, doi:10.1093/database/bav071 (2015).

Pandit, S. et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals SR protein cooperation and competition in regulated splicing. Molecular Cell 50, 223–235, doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.001 (2013).

de Miguel, F. J. et al. Identification of alternative splicing events regulated by the oncogenic factor SRSF1 in lung cancer. Cancer Research 74, 1105–1115, doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1481 (2014).

Storbeck, M. et al. Neuronal-specific deficiency of the splicing factor Tra2b causes apoptosis in neurogenic areas of the developing mouse brain. PLoS One 9, e89020, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089020 (2014).

Masuda, S. et al. LSR defines cell corners for tricellular tight junction formation in epithelial cells. Journal of Cell Science 124, 548–555, doi:10.1242/jcs.072058 (2011).

Song, S., Rosen, K. M. & Corfas, G. Biological function of nuclear receptor tyrosine kinase action. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 5, a009001, doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a009001 (2013).

Kitagawa, M. Notch signalling in the nucleus: roles of Mastermind-like (MAML) transcriptional coactivators. Journal of Biochemistry 159, 287–294, doi:10.1093/jb/mvv123 (2016).

Watanabe, K. et al. ILDR2: an endoplasmic reticulum resident molecule mediating hepatic lipid homeostasis. PLoS One 8, e67234, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067234 (2013).

Wu, J. Y. & Maniatis, T. Specific interactions between proteins implicated in splice site selection and regulated alternative splicing. Cell 75, 1061–1070 (1993).

Kohtz, J. D. et al. Protein-protein interactions and 5′-splice-site recognition in mammalian mRNA precursors. Nature 368, 119–124, doi:10.1038/368119a0 (1994).

Shen, H., Kan, J. L. & Green, M. R. Arginine-serine-rich domains bound at splicing enhancers contact the branchpoint to promote prespliceosome assembly. Molecular Cell 13, 367–376 (2004).

Shen, H. & Green, M. R. A pathway of sequential arginine-serine-rich domain-splicing signal interactions during mammalian spliceosome assembly. Molecular Cell 16, 363–373, doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.021 (2004).

Caceres, J. F., Misteli, T., Screaton, G. R., Spector, D. L. & Krainer, A. R. Role of the modular domains of SR proteins in subnuclear localization and alternative splicing specificity. The Journal of Cell Biology 138, 225–238 (1997).

Kataoka, N., Bachorik, J. L. & Dreyfuss, G. Transportin-SR, a nuclear import receptor for SR proteins. The Journal of Cell Biology 145, 1145–1152 (1999).

Chang, P. & Stearns, T. Delta-tubulin and epsilon-tubulin: two new human centrosomal tubulins reveal new aspects of centrosome structure and function. Nature Cell Biology 2, 30–35, doi:10.1038/71350 (2000).

Smrzka, O. W., Delgehyr, N. & Bornens, M. Tissue-specific expression and subcellular localisation of mammalian delta-tubulin. Current Biology 10, 413–416 (2000).

Kato, A., Nagata, Y. & Todokoro, K. Delta-Tubulin is a component of intercellular bridges and both the early and mature perinuclear rings during spermatogenesis. Developmental Biology 269, 196–205, doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.026 (2004).

Otto, E. A. et al. Nephrocystin-5, a ciliary IQ domain protein, is mutated in Senior-Loken syndrome and interacts with RPGR and calmodulin. Nature Genetics 37, 282–288, doi:10.1038/ng1520 (2005).

Barbelanne, M., Hossain, D., Chan, D. P., Peranen, J. & Tsang, W. Y. Nephrocystin proteins NPHP5 and Cep290 regulate BBSome integrity, ciliary trafficking and cargo delivery. Human Molecular Genetics 24, 2185–2200, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddu738 (2015).

Depienne, C. et al. Sporadic infantile epileptic encephalopathy caused by mutations in PCDH19 resembles Dravet Syndrome but mainly affects females. PLoS Genetics 5, e1000381, doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000381 (2009).

Hynes, K. et al. Epilepsy and mental retardation limited to females with PCDH19 mutations can present de novo or in single generation families. Journal of Medical Genetics 47, 211–216, doi:10.1136/jmg.2009.068817 (2010).

Jamal, S. M., Basran, R. K., Newton, S., Wang, Z. Y. & Milunsky, J. M. Novel de novo PCDH19 mutations in three unrelated females with epilepsy female restricted mental retardation syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics A 152A, 2475–2481, doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.33611 (2010).

Xu, Z., Peng, A. W., Oshima, K. & Heller, S. MAGI-1, a candidate stereociliary scaffolding protein, associates with the tip-link component cadherin 23. The Journal of Neuroscience 28, 11269–11276, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3833-08.2008 (2008).

Cao, H. et al. FCHSD1 and FCHSD2 are expressed in hair cell stereocilia and cuticular plate and regulate actin polymerization in vitro. PLoS One 8, e56516, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056516 (2013).

Heller, S., Sheane, C. A., Javed, Z. & Hudspeth, A. J. Molecular markers for cell types of the inner ear and candidate genes for hearing disorders. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95, 11400–11405 (1998).

Florea, L., Song, L. & Salzberg, S. L. Thousands of exon skipping events differentiate among splicing patterns in sixteen human tissues. F1000 Research 2, 188, doi:10.12688/f1000research.2-188.v2 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of our group for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (2013CB967700 to Z.X.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31371355 to Z.X., 31401007 to Y.W.), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2014M560550 to Y.W.), and the Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong University (2014HW011 to Y.W.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W. and Z.X. supervised the present study. Y.L., H.N., C.L, X.Z., Q.S., and Y.W. performed the experiments. Y.L., D.S., L.W., and Z.X. analyzed the data. Y.L. and Z.X. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Nie, H., Liu, C. et al. Angulin proteins ILDR1 and ILDR2 regulate alternative pre-mRNA splicing through binding to splicing factors TRA2A, TRA2B, or SRSF1. Sci Rep 7, 7466 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07530-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07530-z

This article is cited by

-

ILDR1 promotes influenza A virus replication through binding to PLSCR1

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.