Abstract

In this work, we present laser coloration on 304 stainless steel using nanosecond laser. Surface modifications are tuned by adjusting laser parameters of scanning speed, repetition rate, and pulse width. A comprehensive study of the physical mechanism leading to the appearance is presented. Microscopic patterns are measured and employed as input to simulate light-matter interferences, while chemical states and crystal structures of composites to figure out intrinsic colors. Quantitative analysis clarifies the final colors and RGB values are the combinations of structural colors and intrinsic colors from the oxidized pigments, with the latter dominating. Therefore, the engineering and scientific insights of nanosecond laser coloration highlight large-scale utilization of the present route for colorful and resistant steels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Beautifying and passivating metal surfaces is highly time, energy and material consuming process in modern industry. Recently developed laser coloration has been achieved on stainless steel but it has been greatly limited for expensive sources. In addition, the lack of physical knowledge of the mechanism beyond color appearance and performance have prevented the boom of the promising technique. The colorful stainless steel has drawn much attention due to its excellent performance in architectural and decorative applications1. Conventional chemical erosion and electrochemical methods2, 3 to introduce colors on steel surface are gradually abandoned due to the environmental pollution problems. The hunt for a facile and costless method of fabricating colored stainless steel have been active for years by both industrial and academic fields. One feasible route was brought about by femtosecond laser technique, which has been applied successfully in preparing black silicon, iridescent aluminum and blue titanium surfaces4,5,6. The femtosecond laser with high photon energy is efficient at producing laser-induced periodic surface structure (LIPSS) on steel surface7. Such LIPSS surface shows enhanced hydrophobic and corrosion resistant abilities, and is also endowed with abundant colors8,9,10. However, high-cost femtosecond laser is not well suitable for industrial production, while the alternative nanosecond laser was believed that it could only produce limited colors species11. Current researches of these routes mainly stay at the engineering level, just producing series of colors by tuning laser parameters12, 13.

Despite the limitation arisen from materials engineering, mechanisms leading to the surface coloration remain unclear. Coloration of femtosecond laser markings is primarily attributed to the structure color effect, but as for markings fabricated by nanosecond laser, such light-matter interference will be extremely decreased because the surface structure is in a much larger scale than the wavelength of visible light. As for the route employing nanosecond sources, although the color range has been extended gradually14, the coloration mechanism has not been sufficiently studied. Several reports referred to the intrinsic colors of the metal oxides in the laser markings12,13,14, but lack of further approval and discussion. Contributions from different pigments or interferences to RGB values on the decorated steels are not quantified to the best of our knowledge. Therefore, understanding the impact of laser-induced structural and compositional variations on the apparent colors becomes crucial to promote the nanosecond laser marking technique in large-scale industrial applications.

In this work, we carried out a novel study to explore mechanism of nanosecond laser coloration on 304 stainless steel surface, and quantitatively matched the RGB values on the colored steels to the corresponding abundances of oxides determined at atomic level. Square markings with straw-yellow, cornflower-blue and fuchsia colors were prepared under a master-oscillator-power-amplifier (MOPA) laser system in ambient air at room temperature. Structural color effect was studied by both simulation of the thin film interference and measurements of optical reflectance properties. Meanwhile, elemental and chemical states analysis of the marking samples was carried out through X-ray photoelectron spectroscope (XPS). The compositional color contribution was thus quantitatively discussed.

Results

Color information

Various colors were formed on the mechanically polished 304 steel surfaces via the low-cost and fast nanosecond pulse laser coloration route. A typical radiation time is around 1 minute to color each square with an area of 5 × 5 mm2. Different colors were reached via semi-empirically varying laser scanning speed, repetition rate, and pulse width. The relations between nanosecond laser parameters and final surface performance have been discussed elsewhere12,13,14,15, yet out of the main focus of the present work.

Color information of the laser markings was obtained through polarized light microscope without filters. During the measurements, the incident white light beam was kept perpendicular to the sample surface. As shown in Fig. 1, three colorized samples were prepared, displaying straw-yellow, cornflower-blue and fuchsia colors, respectively. The insets were taken by digital camera with tilted directions (raw photo shown in Supplementary Fig. 1), appearing slightly different colors. To quantitatively describe color information, the commonly used RGB color model is presented here. The RGB model is built following the way in which cone cells in human retina perceive red, green and blue colors16, and all the three color components vary from 0 ~ 255. A larger component value indicates a higher brightness and saturation. In order to get the average RGB values of each photo, the red, green and blue values of each pixel were counted and averaged. Table 1 indeed shows that all the generated colors have relatively low RGB values, or in other words, colors are not fully saturated.

Optical reflectance

Optical reflectance was measured at the incident angle of 30° and 70°, respectively. With Xenon lamp as the light source, the incident light spectrum agreed well with the solar spectrum in the visible light range17. In both Fig. 2a and b, low reflectance values were recorded, yet it is noteworthy that the reflectance increased slightly with the incident angles. This is the characteristic behavior of structural color effect. In general, the presented colors vary in a limited scope. Differences between Fig. 1a~c and the insets suggest a weak influence on the final colors from the aspect of light-matter scattering. Among the three samples, sample 1 exhibits the highest reflectance. Meanwhile, a rise of ~20% in the reflectance indicates that sample 1 is more influenced by the structure color. For each sample, the reflectance roughly increases along with the light wavelength, in accordance with results in previous research18.

Contribution of structural color

To clarify the light-matter interaction, it is essential to acquire the information of morphology and thickness of the laser-induced layer on steel surface. Sample morphologies depicted in Fig. 3a–c show that the surfaces are basically composed of irregular micro-wrinkles with lateral dimensions in 10 µm scale, much larger than the wavelength of visible light. Thus, possibility of light interference with the microstructure is rather low19. Although sample 1 and 2 show distinct colors, their microstructures are quite similar except that the wrinkles in sample 1 are larger and arranged more sparsely. Short-order periodic grooves appear in sample 2 (Fig. 3b), but their influence on the coloration can be still neglected due to the lack of quantity. In Fig. 3c, there are uniformly arranged gratings. However, the periodic length is around 8 ~ 12 µm, far from the coherent length to interfere with visible light. Therefore, the structural color effect may only originate from the light interference with the laser-generated film.

The film on top of steel surface was formed during laser treatment, and its thickness can be estimated through surface profile measurements. The layer thickness of sample 2 is ~300 nm, while the other two are approximately 800 nm (Supplementary Fig. 2). As an alternative non-destructive technique, ellipsometry method20 was also employed to double-check the thickness. For sample 2, the ellipsometry method gave the thickness of 314.4 ± 37.6 nm (Supplementary Fig. 3), which is very close to the surface profiler result (300 nm). However, such a method could not be accomplished for sample 1 and sample 3, even with the AutoRetarder which allows depolarization for surface of certain roughness. It might be due to rather high roughness and limited region of the laser induced films, which are beyond the applicability of the surface-sensitive ellipsometry method21. In this case, we carried out cross-sectional scanning electron microscope (SEM) measurement in order to directly obtain the film thicknesses (Supplementary Fig. 4). Values of 764.1 ± 31.7 nm, 338.1 ± 20.9 nm and 807.6 ± 54.2 nm were found for sample 1–3, respectively, in good agreement with the optical profilometer results.

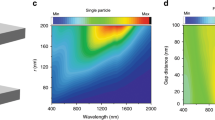

Simulation work was carried out to evaluate the reflective ability coming from thin-film interference. Smooth film models were built, and the morphology information on the surface was discarded. The layer thickness was set according to the surface profile results, while incident light set perpendicularly. The refractive indices and extinction coefficients were set based on ellipsometry measurement results. The simulated results in Fig. 3d have the same trend of wavelength dependence as the experimental determinations in Fig. 2. However, discrepancies of ~10% have been found between the calculated and measured reflectance for sample 2 and sample 3. This can be attributed to typical simplifications of theoretical models and homogeneity of materials employed in the simulations22, 23. Indeed, even for a surface composed of single element (e.g., bare silicon surface), theoretical results22 can still vary more than 10% against experimental ones24. In spite of the discrepancies, no obvious peaks can be observed in the reflectance curves. Thus, structural coloration does not dominate final colors on the nanosecond laser marked surfaces.

Quantification of compositions

Quantitative analysis of surface compositions is the prerequisite to evaluate the composition based coloration mechanism. By the energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), we roughly examined the elemental information of the samples. Fe, Cr, Ni and Mn were the primary elements, and more Cr was detected in sample 1 (see Supplementary Table 1). Since the detection depth of EDS (~1 µm)25 is much larger than the film thickness, EDS result was mixed up with elemental information coming from substrates, making it inappropriate to analyze the thin films on the surface.

XPS is a surface sensitive technique and thus available to focus on the thin markings. Figure 4 shows the XPS spectra of Cr 2p, Fe 2p and the details of peak fitting are listed in Supplementary Table 2. For Cr 2p spectra, two groups of peaks were identified in Fig. 4a, which were Cr2O3 at ~576.5 eV and a spinel structure at ~575.4 eV, respectively26, 27. The typical spinel structure is XY2O4, where X and Y represent ions in +2 and +3 valence28. In this work, its form can be specified as (Mn2+ x1Ni2+ x2Fe2+ x3)(Fe3+ x4Cr3+ x5)O4, where x1 + x2 + x3 = 1 and x4 + x5 = 2. In contrast, the spinel peaks disappeared on the spectra of steel substrates, and chromium of metal form was detected (Supplementary Fig. 5). Similar results are also found in Fig. 4b. The spinel compound and Fe2O3 were identified. As a typical feature for Fe 2p spectra of stainless steel, the pair of satellite peaks of spinel compound were also specified. It suggests that the spinel structure was formed during the laser treatment process.

XPS spectra of: (a) Cr 2p, (b) Fe 2p. In each panel, the spectra of the three samples are illustrated. Each pair of doublet peaks were illustrated with identical color. The scatter plots are experimental results, while the magenta and grey lines represent the fitting envelopes and backgrounds, respectively.

Indeed, native passivation layer on stainless steel surface is mainly composed of Cr2O3, Fe3O4 and Fe2O3 29. Alloy elements were promoted to disperse from the substrate to the passivation layer due to the heat effect of pulsed laser, and they could be more easily oxidized by oxygen. Oxygen partial pressure was therefore reduced, producing a reductive atmosphere in local region. In this case, Cr and Mn have the priority to react with the remaining oxygen and form their metal oxides. After that Fe was also oxidized to FeO, meanwhile, laser beam moved away and the temperature as well as the reaction rate dropped consequently. Oxygen partial pressure rose, which facilitated the simultaneous oxidization of Fe, Ni and the metal oxides. The spinel compound was then formed. It was also possible for Cr3+ substituted by Fe3+, making the spinel structure even more complicated30.

It is noteworthy that very small amount of Ni was detected although there was 8~11% in the commercial 304 steel substrate (see Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6). Ni is nearly absent in the native passivation layer, while that in the substrate usually completely dissolved in γ–Fe, making it difficult to escape31. The EDS results indicated more than 6% of Ni, most of which should come from the substrates.

Discussion

Obvious discrepancies between the real colors on the surfaces and optical determinations demand further investigations of the color origins of the laser treated steel surface. It has been noticed the metal oxides, especially well crystalized ones, can also act as stable pigments. Thus, in the following, we carefully examined chemical components on the surfaces, and estimated their contributions to the RGB values. The XPS fitting results provide quantitative information of each element in the sample. For Cr 2p, Fe 2p, Mn 2p and Ni 2p spectra, each spectrum was fitted with two components: the metal oxide and the spinel compound. Based on the atomic percentage of the metal ions (in metal oxides), the relative contents of their metal oxides could be easily obtained by dividing the subscript numbers. That is,

where C MO , C ion and n i are the relative contents of metal oxides, the elemental percentage of ions in the metal oxides, and their subscript numbers, respectively. Similarly for the ions in the spinel (Mn2+ x1Ni2+ x2Fe2+ x3)(Fe3+ x4Cr3+ x5)O4, divided by the corresponding subscripts, the relative content of spinel could be calculated through any of the metal ions.

where C spinel , C s-ion and x i are the relative content of the spinel, the elemental percentage of metal ions in the spinel and their subscript numbers in the molecular formula. Through equations (1) and (2), we can calculate the relative contents of each metal oxide and the spinel, and also the ratios of each ion in the spinel. The relative contents of all the metal oxides and spinel compounds were normalized and tabulated in Table 2. The quantified molecular formula of the spinels are (Mn2+ 0.12Fe2+ 0.88)(Fe3+ 1.12Cr3+ 0.88)O4, (Mn2+ 0.07Ni2+ 0.09Fe2+ 0.84)(Fe3+ 1.82Cr3+ 0.18)O4 and (Mn2+ 0.07Ni2+ 0.04Fe2+ 0.89)(Fe3+ 1.80Cr3+ 0.20)O4 for samples 1–3, respectively.

Compositions in the laser marking film, say the metal oxides and the spinel compound, are natural pigments presenting distinct colors. RGB values of metal oxides were set according to previous studies of their pure form32, 33. However, it becomes complicated when figuring out the color of the spinel. Its color is highly influenced by Cr, Fe elements, yet unfortunately affirmative relationships between the ratios and colors remain unknown. What’s more, the Fe2+ and Fe3+ have different influence to the colors, and colors change drastically even with a small amount variation. Therefore we propose that the metal oxides and the spinel contribute their own color (in RGB values) by a factor of their relative contents, while the color of the spinel is qualitatively dominated by the existing Fe2+, Fe3+ and Cr3+. Fe2+ in the spinel results in a blue color species, varying among grey-blue, violet-blue and even dark green34. In contrast, enrichment of Fe3+ presents dark brown, while small amount of Fe3+ makes the color prone to green or even blue-green35 when Fe2+ is oxidized to Fe3+. On the other hand, Cr3+ is the key factor of red appearance, which usually give red or pale pink colors to the spinel36. The joint effect of Fe2+ and Cr3+ then produce colors in violet-red or dark violet, but the color will tend to orange when Fe3+ replace part of the Cr3+. The effect of Mn2+ and Ni2+ is not significant due to the very small amount as given by the EDS and XPS results. Mn2+ limitedly enhances the saturation of blue color and thus make it close to yellow37, while the existence of Ni2+ usually produces yellow-green color which is similar to the intrinsic color of NiO38. In general, the spinel presents brown color when Fe2+, Fe3+ and Cr3+ exist simultaneously. Considering the specific amount of metal ions in each sample, we are able to set initial RGB values for the spinels. For sample 1, Fe2+, Fe3+ and Cr3+ have almost the same amount, and much of the Cr3+ ions entered the center of spinel octahedron, making a reddish brown color. Meanwhile, Fe3+ raised the green value, and Mn2+ improved the color saturation and mainly increased blue and green values. Thus spinel color could be revised from standard reddish brown (165, 42, 42) to (165, 110, 95). In sample 2 and 3, the amount of Cr3+ greatly dropped so that the red values would be much smaller than in sample 1. Compared to sample 3, there are more Fe3+ in sample 2 which make a higher saturation of blue. It also contains relatively more Ni2+, tending the color closer to green. The spinel color then was set as (65, 130, 150). Fe3+ are two times more than Fe2+ in sample 3, and it usually presents dark grey (105, 105, 105) in this case. With more Cr3+ and less Ni2+ than in sample 2, red value would be larger and green value became smaller. (90, 95, 105) should be a reasonable value for the spinel in this sample.

With the contents as well as the RGB values of metal oxides and the spinel, RGB values of each sample can be calculated by the product of its color matrix and content matrix,

where R i , G i , B i are the red, green and blue values of Cr2O3, Fe2O3, MnO, NiO and the spinel compound, respectively; C i represents the contents of those compositions. The calculated RGB values agree well with the experimental results (see Table 2). For each sample, both the calculated and measured RGB results are within the same color species although minor differences exist. Such difference may come from the specification of initial spinel colors, but the structural color effect should be also accounted. Despite the surface microstructure of the laser markings, the interference between the thin film and visible light contributes to the final colors depending on its thickness.

In conclusion, we treated the surface of 304 stainless steel with nanosecond laser and studied the coloration mechanism. Different from the femtosecond laser source, nanosecond laser fabricated surface structures in ~20 µm scale, far from the range of visible light wavelength. Therefore the structural color effect was quite weak and the colors of the laser markings were dominantly contributed by the colorful metal oxides and spinel compound. The contribution should be weighted by the relative content of each components. Such findings would be beneficial to the application of low-cost nanosecond laser in surface treatment of steel and other metallic materials.

Methods

Preparation

In this work, the commercial AISI 304 stainless steel was used as the substrate (18~20% Cr, 8 ~ 11% Ni, ≤2% Mn and ≤1% Si) with the thickness of 1 mm. Mechanical polishing was applied before laser treatment in order to produce a smooth surface, and the samples were then cleaned with ethanol. The laser treatment was carried out under a nanosecond MF20-E-A fiber laser marking machine in ambient air at room temperature at Han’s Laser Inc., China. The output power was set as 20 W, generating pulsed laser beam with the central wavelength of 1064 nm. During the laser marking process, the maximum pulse energy was 1.10 mJ at the pulse repetition rate of 45–500 kHz and the scanning speed of 100 mm/s–1300 mm/s, while the pulse width was tuned from 4 ns to 260 ns. Scanning steps varied during the laser treatment.

Characterizations

Polarized light microscope (Nikon Eclipse LV100DA-U) was employed to acquire the color information of the marked steel surface. The light source is within visible wavelength range without optical filters. Low magnification was adopted so that the colorized surface could be recorded in a relatively large scale. Optical properties including reflectance, refractive index and extinction coefficient were measured by an UVISEL-VASE Horiba Jobin-Yvon ellipsometer with a fixed incident angle of 70°. Reflectance behavior was also taken by an UV-vis-NIR Varian Cary 500 spectrophotometer. For the purpose of comparative analysis, the incident angle of the spectrophotometer was set as 30° degree.

The microstructure morphology was characterized by a Zeiss ULTRA plus FESEM. Surface roughness and film thickness were measured by optical profilometer (Bruker ContourGT-K). Ellipsometer (VASE) and cross-sectional SEM were also applied to double-check the thickness. During ellipsometry measurements, the polarization orientation (Ψ) and polarization phase (Δ) were measured with the AutoRetarder. Regression analysis was used to match the experimental data and calculate the thickness. For cross-sectional SEM measurements, the laser marking samples were cut and inlaid with epoxy resin. The image quality was limited due to the weak conductivity of the metal oxides in the laser marking film.

We roughly examined the element contents of each laser marking through EDS. A Thermo Fisher Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi XPS spectrometer was used for detailed analysis of the final chemical states. All XPS spectra were calibrated with C 1 s (248.8 eV) and then fitted.

Simulation

Numerical simulation of light scattering was carried out in the finite differential time domain (FDTD). The OptiFDTD software (free version) was employed here, and the simulations were based on the space and time partial derivatives of discrete time-dependent Maxwell’s equations. From the experimental point of view, the lateral dimensions of surface morphologies have weak interference with visible light, and this was also approved by series of simulation tests. Therefore, models of laser markings were established in thin film interference mode with smooth surface in order to improve the simulation speed. In the two-layer models, the lower layer was stainless steel substrate and the upper one was the laser marking film. The refractive indices of these two layers were defined according to the experimental results. In the simulations, we employed the refractive indices at the wavelength of 550 nm which were recommended by the OptiFDTD software. These are, n 1 = 1.104 + 1.607i, n 2 = 2.198–1.045i, n 3 = 1.929 + 0.775i, n 4 = 2.586 + 2.413i for the laser marking films in samples 1–3 and the steel substrates, respectively. The thickness of steel substrate was fixed as 1 µm, while the values were 800 nm, 300 nm and 800 nm for samples 1–3, respectively. Perpendicular input plane light source was set up as Gaussian modulated continuous wave with wavelength from 400 nm to 700 nm. The boundary conditions in X and Y directions were set as Periodic Boundary Condition (PBC), while Anisotropic Perfectly Matched Layers (APML) in Z direction. To receive reflective information, the observation points were set directly above the models.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chater, J. Polychrome: the many colours of stainless steel. Stainless Steel World 3, 1–4 (2014).

Kikuti, E., Conrrado, R., Bocchi, N., Biaggio, S. R. & Rocha-Filho, R. C. Chemical and electrochemical coloration of stainless steel and pitting corrosion resistance studies. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 15, 472–480 (2004).

Taveira, L. V., Kikuti, E., Bocchi, N. & Dick, L. F. Microcharacterization of colored films formed on AISI 304 by different electrochemical methods. J. Electrochem. Soc. 153, B411–B416 (2006).

Vorobyev, A. Y. & Guo, C. Direct creation of black silicon using femtosecond laser pulses. Appl. Sur. Sci. 257, 7291–7294 (2011).

Vorobyev, A. Y. & Guo, C. Colorizing metals with femtosecond laser pulses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 041914 (2008).

Vorobyev, A. Y. & Guo, C. Metal colorization with femtosecond laser pulses. Proc. SPIE 7005, 70051T (2008).

Milovanović, D. S. et al. Femtosecond laser surface patterning of steel and titanium alloy. Phys. Scr. T162, 014017 (2014).

Gu, Z.-Z. et al. Structural color and the lotus effect. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 894–897 (2003).

Łęcka, K. M. et al. Effects of laser-induced oxidation on the corrosion resistance of AISI 304 stainless steel. J. Laser Appl. 28, 032009 (2016).

Ahsan, M. S., Ahmed, F., Kim, Y. G., Lee, M. S. & Jun, M. B. Colorizing stainless steel surface by femtosecond laser induced micro/nano-structures. Appl. Sur. Sci. 257, 7771–7777 (2011).

Guo, Q. L., Li, X. H., Zhang, Y. & Huang, W. The comparison of fabricating colorful patterns on stainless steel with femtosecond and nanosecond laser pulses. ICEOE 2011 2, 69–71 (2011).

Veiko, V. et al. Development of complete color palette based on spectrophotometric measurements of steel oxidation results for enhancement of color laser marking technology. Materials & Design 89, 684–688 (2016).

Veiko, V. et al. Controlled oxide films formation by nanosecond laser pulses for color marking. Optics Express 22, 24342–24347 (2014).

Li, Z. L. et al. Analysis of oxide formation induced by UV laser coloration of stainless steel. Appl. Sur. Sci. 256, 1582–1588 (2009).

Antończak, A. J. et al. The influence of process parameters on the laser-induced coloring of titanium. Appl. Phys. A 115, 1003–1013 (2014).

Hunt, R. W. G. The Reproduction of Colour. (Wiley–IS&T Series in Imaging Science and Technology, 2004).

Ye, C. et al. Rapid cycling of reactive nitrogen in the marine boundary layer. Nature 532, 489–491 (2016).

Luo, F. et al. Study of micro/nanostructures formed by a nanosecond laser in gaseous environments for stainless steel surface coloring. Appl. Sur. Sci. 328, 405–409 (2015).

Ball, P. This season’s colours. Nature Mater. 15, 709–709 (2016).

Zheng, H. Y., Lim, G. C., Wang, X. C., Tan, J. L. & Hilfiker, J. Process study for laser-induced surface coloration. J. Laser Appl. 14, 215–220 (2002).

Losurdo, M., Hingerl, K. Ellipsometry at the Nanoscale. (Springer, 2013).

Huang, Z. et al. A computational study of antireflection structures bio-mimicked from leaf surface morphologies. Solar Energy 131, 131–137 (2016).

Huang, Z. et al. Structural color model based on surface morphology of morpho butterfly wing scale. Surf. Rev. Lett. 23, 1650046 (2016).

Sardana, S. K. & Komarala, V. K. Optical properties of hybrid plasmonic structure on silicon using transparent conducting-silver nanoparticles–silicon dioxide layers: the role of conducting oxide layer thickness in antireflection. J. Opt. 18, 075004 (2016).

Vickerman, J. C. & Gilmore, I. S. Surface Analysis - The Principal Techniques. (John Wiley & Sons, 2009).

Allen, G. C., Harris, J. A., Jutson, J. A. & Dyke, J. M. A study of number of mixed transition metal oxide spinels using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Appl. Sur. Sci. 37, 111–134 (1998).

Huntz, A. M. et al. Oxidation of AISI 304 and AISI 439 stainless steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 447, 266–276 (2007).

Biagioni, C. & Marco, P. The systematics of the spinel-type minerals: An overview. Am. Mineral. 99, 1254–1264 (2014).

Simões, A. M. P., Ferreira, M. G. S., Rondot, B. & da Cunha Belo, M. Study of passive films formed on AISI 304 stainless steel by impedance measurements and photoelectrochemistry. J. Electrochem. Soc. 137, 82–87 (1990).

Levinstein, H. J., Robbins, M. & Capio, C. A crystallographic study of the system FeCr2O4-Fe3O4 (Fe2+ Fe3+ xCr2−xO4). Mater. Res. Bull. 7, 27–34 (1972).

Pickering, F. B. Physical metallurgy and the design of steels. (Applied Science Publishers, 1978).

Liang, S.-T. et al. Preparation of Cr2O3-based pigments with high NIR reflectance via thermal decomposition of CrOOH. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China. 25, 2646–2652 (2015).

Torrent, J. & Barrón, V. Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy of iron oxides. Encyclopedia of Surface and Colloid Science. 1, 1438–1446 (2002).

Muhlmeister, S. et al. Flux-grown synthetic red and blue spinels from Russia. Gems Gemol. 29, 81–98 (1993).

D’Ippolito, V. et al. Color mechanisms in spinel: cobalt and iron interplay for the blue color. Phys. Chem. Miner. 42, 431–439 (2015).

Huong, L. T.-T. et al. Gemstones from Vietnam: an update. Gems Gemol. 48, 158–176 (2012).

Llusar, M. et al. Stability and coloring properties of Ni-qandilite green spinels (Ni, Mg)2 TiO4: The “half color wheel” of Ni-doped magnesium titanates. Dyes Pigments. 122, 368–381 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Han’s Laser Inc. China, for preparations, discussions, and parameter optimizations of the nanosecond laser marking. This work is financially supported by Oulu University Strategic Grant, and the Academy of Finland. Y.L. acknowledges the supports from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51201061), International Cooperation Project from Henan Province (Grant No. 172102410032), and Science and Technology Innovation Team of Henan University of Science and Technology (2015XTD006). Y.L. and X.S. acknowledge the scholarship sponsored by China Scholarship Council. The Center of Microscopy and Nanotechnology of Oulu University, and Q. Wang at Tsinghua University are also acknowledged for sample characterizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was initiated, conceived and conducted by W.C., Y.L. and X.S. performed the SEM, XPS and optical reflectance measurements, and X.S. computed RGB values through chemical state determinations. J.C., Y.L. and T.F. took the surface profile and optical microscope photos. Y.L. and Z.H. carried out the FDTD simulations, while T.L. and M.Z. in searching for connections between pigments and coloration. X.S., Y.L. and W.C. wrote the manuscript, with general supervisions from M.H. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, Y., Shi, X., Huang, Z. et al. Nanosecond laser coloration on stainless steel surface. Sci Rep 7, 7092 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07373-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07373-8

This article is cited by

-

Unveiling nano-scaled chemical inhomogeneity impacts on corrosion of Ce-modified 2507 super-duplex stainless steels

npj Materials Degradation (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.