Abstract

One of the main challenges for highly sensitive surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) detection is the noise interference of fluorescence signals arising from the analyte molecules. Here we used three types of gold nanostars (GNSs) SERS probes treated by different surface modification methods to reveal the simultaneously existed Raman scattering enhancement and inhibiting fluorescence behaviors during the SERS detection process. As the distance between the metal nanostructures and the analyte molecules can be well controlled by these three surface modification methods, we demonstrated that the fluorescence signals can be either quenched or enhanced during the detection. We found that fluorescence quenching will occur when analyte molecules are closely contacted to the surface of GNSs, leading to a ~100 fold enhancement of the SERS sensitivity. An optimized Raman signal detection limit, as low as the level of 10−11 M, were achieved when Rhodamine 6 G were used as the analyte. The presented fluorescence-free GNSs SERS substrates with plentiful hot spots and controllable surface plasmon resonance wavelengths, fabricated using a cost-effective self-assembling method, can be very competitive candidates for high-sensitive SERS applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) active substrate is currently a hot topic in highly sensitive optical spectral sensing applications because of its short time-consumption and reproducibility1,2,3,4. Uniformly distributed metal nanostructures with abundant hot spots supporting localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) are the critical elements for high-sensitivity SERS active substrates5, 6. The hot spots mainly at the sharp tips of metal nanostructures produce a strongly localized electromagnetic field enhancement, which is beneficial for SERS signal enhancement. Therefore, metal nanostructures with densely packed sharp tips, such as nanostars7,8,9,10 and nanoplates11,12,13,14,15 are the best promising candidates for high-performance SERS probes.

To obtain such nanostructures with well controlled morphology and size for SERS application, chemical synthesis methods were usually used4, 9, 12, 16. However, such chemically synthesized metal nanostructures containing organic shells (capping agents, or modifier)17 always generate serious background fluorescence noise which limits the SERS detection sensitivity greatly. Although this phenomenon has already been observed in many SERS detection experiments18,19,20, few methods were proposed to solve this problem. The only proposed strategy to avoid the influence of fluorescence is changing the excitation wavelength for the Raman measurement to longer wavelengths21,22,23. However, when excitation wavelength with lower photon energy was used, the SERS enhancement factor (EF) would also be decreased obviously. Therefore, SERS detection strategies which could effectively inhibit the fluorescence noise without decreasing, or even increasing SERS EF are highly expected.

In this paper, we focused on the performance improvement of SERS substrates self-assembled by chemical synthesized gold nanostars (GNSs). We investigated the phenomenon that the Raman scattering enhancement and inhibiting fluorescence during SERS detection process simultaneously existed, which greatly influenced the SERS EF. Based on plasmon-induced surface resonance energy transfer theory, we precisely controlled the space between the metal and organic molecules by surface modification of GNSs to inhibit the fluorescence in SERS measurement, rather than simply changing the excitation wavelength. Once the fluorescence was inhibited, we obtained sensitive GNSs SERS probes with optimum sensitivity 102 times higher than the original ones which is a very competitive result for high-sensitivity SERS detection. Meanwhile, we showed various technologies including precise control of GNSs morphology, large-scale and uniform preparation of GNSs substrates and several surface modification methods for molecules distance control, which can be widely applied in the fields of optical sensing, processing and display.

Results and Discussions

High-yield GNSs characterization

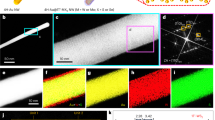

First, we chemically synthesized GNSs with well-controlled morphology as SERS probes combined from previously reported methods24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. High-yield (~100%) GNSs samples with different length of tips were obtained as shown in Fig. 1a. Each GNS was comprised of a quasi-sphere core (~50 nm) and several sharp tips. We also observed there was organic shell on the surface of GNSs (the upper part of Fig. 1b). The thickness of organic shell was about 3 nm. It is interesting that the length of tips on GNSs can be well-controlled by adjusting AgNO3 concentration. Therefore, the hot spots mainly located on the tip (red circle in Fig. 1a) increased with the increased concentration of AgNO3. The crystalline structure of the GNSs can be identified from the high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image of the GNSs in Fig. 1b. The spacing between adjacent lattice planes is 0.23 nm. It corresponds to the <111> lattice plane of face-centered cubic (fcc) Au28,29,30. The fast Fourier transform (FFT) patterns obtained from the above HRTEM image (the lower part of Fig. 1b) shows a hexagonal symmetry diffraction pattern, which indicates that the tips of GNSs are single-crystal with the growth direction of Au <111>. Therefore, the overall results demonstrate that the synthesized GNSs with high uniformity and single-crystal property facilitate the fabrication of reproducible SERS substrates.

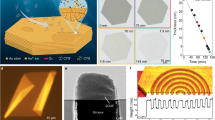

Figure 2a shows the relationship between the morphologies and concentrations of AgNO3. Four samples, named GNS1 to GNS4, were synthesized to show the important role of hot spots for SERS. Meanwhile, with the increase length of tips, as well as the improvement of the anisotropy of GNSs, the color of the GNSs solutions changed from purple to blue as shown in the inset of Fig. 2b. Accordingly, the spectral measurement (Fig. 2b) indicates the LSPR bands11, 25 of the GNSs solution red-shifted, covering the entire Vis-NIR region. It provides various choices for SERS probing in both the visible and NIR diagnostic windows28.

(a) Representative TEM images of GNSs synthesized with different AgNO3 concentrations (GNS1: 5 mM, GNS2: 10 mM, GNS3: 20 mM, GNS4: 30 mM). (b) Normalized extinction spectra of the GNSs solutions, (inset) solutions photographs and (c) GNSs films correspond to the above four samples, (inset) films photographs.

Preparation and characterization of SERS substrates

A simple and effective assistance-free self-assembly process was used to fabricate SERS substrates with large-scale monolayer and uniformly distributed GNSs. ITO glass slabs with a size of 1 × 3 cm were washed by using ultrapure water first. Then, the cleaned ITO glass slabs were immersed in GNSs solutions for 12 h. The GNSs solutions were used without any post-processing after producing by ‘GNSs synthesis’ section method. We also compared the effect of the immersion time on the distribution of GNSs on glass slabs. It was found that the GNSs’ distribution became stable and did not change obviously after 12 h even when they were immersed more time. The corresponding extinction spectra of films from GNS1 to GNS4 are shown in Fig. 2c. The extinction spectra of the four films were all broadening compared with that of the corresponding solutions. Meanwhile, the resonance band of films had a blue shift of dozens of nanometers. This phenomenon can be attributed to the variation of surrounding environment and the aggregation of GNSs on the substrates11, 32. The insets of Fig. 2c showed the photographs of GNSs films, indicating the uniformity of GNSs films in large scale. The SEM images of samples GNS1 and GNS4 were shown in Fig. 3a and b, respectively. The insets of these two figures clearly showed the morphological differences between these two samples. Note that, as the densities of the two films are on the same order of magnitude, the SERS EF is mainly influenced by the morphology, i.e. the length of tips of GNSs.

SERS measurements of GNSs SERS substrates

Next, we investigated the SERS performance of these four GNSs substrates with a series of experimental comparisons. First, we verified the importance of the tips. Figure 4 showed the SERS spectra of GNSs SERS probes (GNS1 to GNS4) when Rhodamine 6G (R6G) molecules with a concentration of 10−7 M were employed as the analyte. Typical Raman characteristic peaks of R6G are clearly shown in these curves which are well matched with the results shown in the published literature33. Meanwhile, it is clearly seen that the GNS4 SERS probes with the longest tip displayed the strongest SERS signal, owing to the well-known hot spots effect34. For electromagnetic enhancement of SERS, the enhancement factor is proportional to the fourth power of the localized light intensity confined on the surfaces of metal nanostructures35. It has been verified that a single hot spot induced electromagnetic enhancement factor can reach as high as 109, which is 3 to 4 orders of magnitude higher than that of an isolated metal nanoparticle. Therefore, SERS enhancement factor of metal nanostructures with plenty of hot spots is much higher than that of conventional spherical nanoparticles. For GNS4, due to the morphology complexity and anisotropic tip distribution, the resonant wavelength of different hot spots in GNS were quite different and extended to a much wider wavelength range far away from the main LSPR peak corresponding to their different dipole moments. Although their LSPR band dependent on their macroscopical distribution of mean size had red-shifted to a wavelength longer than the excitation wavelength, it still enable the excitation of a lot of hot spots contributing to the SERS enhancement at the excitation wavelength and led to a SERS enhancement factor much higher than other samples short of tips.

Then, we focused on the inhibition of fluorescence noise during the SERS detection. As described above, in Fig. 1b, there are organic shells on the surface of GNSs, blocking the direct contact between the surface of metal and R6G molecules. We believe the existence of the organic shells will generate strong fluorescence noise, leading to the decrease of SERS signals. To verify this suspicion, we designed a series of experiments. We used acetone to dissolve the organic shells of GNSs by immersing the SERS substrates into acetone solution for different time. We put the glass slabs in a 50 mL beaker and then added acetone solvent quickly. We took the samples out of the beaker at different time (1 minute, 3 minutes, 3.5 minutes and 5 minutes). Finally, the samples were used as the SERS substrate in the next experiments. After the immersion of 10−7 M R6G, we compared the SERS performance of these samples, as shown in Fig. 5. The SERS EF was calculated by the reported method36. It is defined as EF = (I SERS /C SERS )/(I 0 /C 0 ), where I 0 corresponds to the peak value of Raman signal obtained under ITO glass substrate at an R6G concentration of 10−2 M (Supplementary, Fig. S3). I SERS corresponds to the peak value of Raman signal obtained under GNSs SERS substrate at an R6G concentration of 10−7 M. Here, the intensity at 1363 cm−1 Raman peak was selected as a reference value to compare the SERS EF, as illustrated in the inset of Fig. 5. When immersion time increased from 0 to 3.5 minutes, the SERS EF increased obviously. During this period, organic molecules on the surface of GNSs were dissolved, resulting in gradual decrease of the space between the metal and R6G molecules. To further verify this view, Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrum was used to analyze the elements adsorbed onto the surface of GNSs before and after immersing in the acetone solution respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1). The results indicated that the organic molecules have been effectively dissolved after acetone immersion as we discussed above. With further increase of immersion time, the SERS EF decreased instead. It is because GNSs probes gradually decomposed without the protection of organic shells after long-time immersion. This can be directly seen from TEM image of GNS4 after acetone immersion of 5 minutes as shown in Fig. S2. The results exhibited that the sharp tips of GNS4 became much shorter or even disappeared. We also measured the extinction spectra of GNS4 with different immersion time in acetone as shown in Fig. S2(d). An obvious blue-shift of the maximum extinction wavelength can be observed from the comparison of these extinction spectra, which indicated the removal of organic shells and the decomposition of tips of GNS4 by acetone solvent.

Figure 6a shows the SERS spectra acquired when the original GNS4 probe was adsorbing R6G molecules with different concentrations. A detection limit of R6G up to 10−9 M was obtained. While using the optimal treatment condition (3.5 minutes immersion), a detection limit as low as 10−11 M was obtained by using GNS4 substrates as shown in Fig. 6b. It corresponds to a ~100 fold enhancement of the SERS sensitivity. This enormous improvement of the SERS sensitivity is attributed to the following two reasons. The first one is the Raman signal enhancement due to the distance decrease between the metal nanostructures and the analyte molecules, and the second one is the significant fluorescence inhibition of analyte molecules due to the direct schottky contact between metal and molecules. Because SERS signal is easily annihilated among strong background fluorescence, fluorescence inhibition could effectively contribute to the SERS signal trace detection. To verify the positive contribution of fluorescence inhibition on the SERS enhancement, we did a comparison experiment using adenine as an SERS analyte. Adenine is also a widely used SERS analyte, however, with a much weaker fluorescence compared with R6G. When such analytes are used, one can obtain the relationship between the SERS enhancement and the distance change between the analyte and the metal nanostructures without the influence of fluorescence. The SERS spectra of adenine molecules were obtained for original GNS4 probe at different concentrations as shown in Fig. S4(a). We measured a detection limit of R6G up to 10−8 M. While using the optimal treatment condition (3.5 minutes acetone immersion), a detection limit of adenine, as low as 10−9 M, was obtained as shown in Fig. S4(b). The enhanced multiple (~10 fold) of the sensitivity is an order less than that of R6G (~100 fold). This comparison experimental result clearly verified that the Raman signal enhancement due to the distance decrease between the metal nanostructures and the analyte molecules is not the only reason for analyte with strong fluorescence. The much better improvement of SERS sensitivity of R6G molecules is also attributed to the effective fluorescence inhibition after surface modification of GNSs. The above experimental results proved that our proposed surface modification method by acetone immersion of GNS substrate is an effective technique suitable for the improvement of SERS signal of various analyte, especially for trace detection of Raman analyte with strong fluorescence. We also studied the uniformity and time stability of the acetone-treated substrates using the SERS spectrum of R6G shown in Fig. S6. The results showed the good uniformity and the long-term stability of this SERS probe.

To further indicate that the increase of SERS EF arises from both the inhibition of fluorescence and the distance decrease between the metal nanostructures and the analyte molecules, we designed another experiment. It is well known that when the distance between metal nanostructure and fluorescence molecules increased, the fluorescence intensity would be increased by the LSPR of metal nanostructure2. Here SiO2 was used as an isolation layer to increase the space between the metal and R6G molecules (Fig. 7a). The thickness of SiO2 shell was about 10 nm (inset of Fig. 7a). After the immersion of 10−7 M R6G solution, we compared the SERS performance of original GNS4 and GNS4@SiO2 SERS substrates, as shown in Fig. 7b. As expected, the GNS4@SiO2 SERS substrates showed weakened SERS signals due to the strong fluorescence noises. We also compared these two samples with cleaned GNS4 SERS substrates. The normalized (dividing each group of data by their maximum values) Raman spectra (Fig. 7c) of the GNS4@SiO2, original GNS4, and cleaned GNS4 exhibit simultaneously existed Raman scattering enhancement and inhibiting fluorescence. It is clear that with the decrease of the thickness of the shell, fluorescence noises were inhibited while SERS signals enhanced. We also compared the adenine’s SERS performance of original GNS4, cleaned GNS4 and GNS4@SiO2 SERS probes, as shown in Fig. S5. The results were in accordance with that of R6G molecules.

(a) TEM micrograph of the GNS4@SiO2 (inset: higher magnification TEM image for individual GNS4@SiO2). (b) SERS spectra of R6G at a concentration of 1 × 10−7 M for original GNS4 and GNS4@SiO2 probes. (c) normalized Raman spectra of the GNS4@SiO2 (red line), original GNS4 (blue line), and cleaned GNS4 (black line).

As shown in Fig. 8, our whole assumption processes were clearly exhibited by three comparison conceptual graphs. Figure 8a illustrated the original GNS probe with organic shell on the surface of GNSs, which will generate fluorescence noise during the SERS measurement process (the block diagram of Fig. 8a). There were no further post-processing to the metal nanoparticles before the SERS experiments, leading to negative effects in SERS detection in most literatures4, 9, 12, 18,19,20. After immersion treatment in organic solvents such as acetone, the organic shells of GNSs were dissolved at a suitable time and a cleaned GNSs SERS probe was obtained as shown in Fig. 8b. We clearly observed an enhanced SERS signal as well as an inhibition of fluorescence noise when the surface of metal and R6G molecules are closely contacted (the block diagram of Fig. 8b). We have experimentally proved that the effect of acetone is very special, which is slow, gradual and controllable in terms of treating the SERS probes. It could chemically tune the characteristics of the GNSs37. As shown in Fig. 8c, we designedly added an isolation layer of SiO2 to increase the distance between the metal and R6G molecules. It is an effective treatment method in fluorescence enhancement field, but has an extremely negative impact on the SERS detection (the block diagram of Fig. 8c). Thus, on the basis of a series of comparison experiments along with a visual representation, the relationship between Raman scatting and fluorescence of GNSs SERS probes were fully validated. Compared with other methods to remove the surface shells, such as electrochemical method38, plasma cleaning method39 and UV/ozonolysis method40, the current proposed acetone immersion method has advantages of being straightforward, fast, low-cost, and independent on instruments.

The relationship between Raman scattering and fluorescence has been experimentally demonstrated above. Then, we gave further explanation in principle using the plasmon-induced surface resonance energy transfer theory. This newly observed theory described the possible mechanism of the charge transfer enhanced by plasmon-induced hot electron generation at nanoparticle/SiO2 interface, which show potential applications in the development of new-concept optoelectronic devices41. When the GNS is directly contacted with the R6G (Fig. 9a), the hot electron on the surface of GNS has a higher energy than that of S* (excited state) edge of R6G owning to the LSPR properties of metallic nanoparticles. These excited hot electrons will drop to the S* of R6G by the SPR energy transfer. In addition, the R6G molecules itself absorbed a large number of photons, allowing the electrons transfer from the S0 (ground state) to S*(green line). Then, these electrons transfer to the surface of GNS, leading to fluorescence quenching phenomenon due to the non-radiative effect42, 43. In another case (Fig. 9b), organic molecules or SiO2 shells as an isolation layer block the hot electron transfer from S* to the surface of GNS. The high-energy charges will transfer from the S* to S0 directly, increasing the probability of recombination between the electrons and the holes. This charge transfer process will highly enhance the fluorescence radiation in R6G44, 45. This analysis above gives a reasonable explanation to the relationship between the thickness of shells and fluorescence noises observed in experiments.

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated the simultaneously existed Raman scattering enhancement and inhibiting fluorescence during SERS signal detection by a series of comparative experiments. The results indicated that the fluorescence phenomenon is arising from the analyte molecules, which is usually a serious problem in the SERS signal detection, can be greatly inhibited by using suitable surface modification technology. Meanwhile, various technologies including precise control of GNSs morphology, large-scale and uniform preparation of GNSs substrates were also studied. The intrinsic physical mechanisms of the fluorescence quenching effect and SERS enhancement arising from the surface plasmon assisted charge transfer process were systematically investigated. An optimized SERS signal sensitivity, as high as the level of 10−11 M, was achieved when R6G was used as the analyte. Finally, we obtained an optimum sensitivity of GNSs SERS probes which was 102 times higher than that of the original SERS probe, which is a very competitive result for highly sensitive SERS detection. These newly observed physical mechanism and originally demonstrated technological methods may find promising applications in the fields of molecular spectroscopy analysis and nanotechnology.

Methods

Materials

Trisodium citrate (≥99.9%), Sodium silicate solution (27%), (3-Aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane (APTMS, 97%), ascorbic acid (AA, >99.5%) and silver nitrate (AgNO3, >99.9%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Gold chloride trihydrate (HAuCl4⋅3H2O, >99.9%), hydrochloric acid (HCl, >98.0%), Rhodamine 6G (R6G, >99.0%) were purchased from sinopharm chemical reagent Co. Ltd. Ultrapure water from Milli-Q (Millipore, America, resistivity >18.4 MΩ⋅cm) source was used throughout the experiments. All materials were used without further purification.

Seeds synthesis

100 ml of 1 mM HAuCl4⋅3H2O solution were heated to boiling under vigorous stirring. Then 15 ml of 1% trisodium citrate solution was added. The reactant was cooled to stop reaction after 15 minutes boiling.

GNSs synthesis

100 μL of 1 M HCl were added to 100 ml of 0.25 ml HAuCl4⋅3H2O in a 150 ml erlenmeyer flask at room temperature under stirring of 700 rpm. Then 1 ml of seed solution purified by a 0.22 μm nitrocellulose membrane filter was added. Then, 1 ml of AgNO3 solution with a suitable concentration and 500 μl of 100 mM AA solution were added simultaneously. The color of the solution changed rapidly from shiny red to blue. The reaction was completed within 30 s. By tuning the concentration of the AgNO3 solution, a series of GNSs samples with different morphologies were obtained.

GNS@SiO2 synthesis

300 mL of GNS4 solution were centrifuged (4000 rpm, 30 minutes) and redispersed in 100 mL of water. 4 mL of APTMS (1 mM) were then added to dispersed solution and stirred for 15 minutes. Then, 30 mL of Sodium silicate solution (0.54 wt%) were added and stirred for 3 minutes. The reaction solution was heated for 2 h (100 °C, 600 rpm). After centrifuging the solution (4000 rpm, 30 minutes), the GNS4@SiO2 samples were obtained46.

Characterization

The structural features of the GNSs were characterized using scanning electron microscope (SEM, Zeiss Ultra Plus) and transmission electronic microscopy (TEM; Fei Tecnai G20). Optical extinction spectra were measured using the fiber optic spectrometer (NOVA, Ideaoptics Technology Ltd., China). Raman spectra were obtained using the Laser Confocal Raman Micro-spectroscopy (LCRMS, LabRAM HR UV-Visible, France), where 50× long working distance objective lens was used. The laser power is 1.2 mW for 514 nm. The time of acquisition is 10 s. R6G were uniformly attached on the surface of GNSs by immersing SERS substrates into the R6G solution in different concentrations.

References

Xu, L. et al. Multigaps embedded nanoassemblies enhance in situ Raman spectroscopy for intracellular telomerase activity sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 1602–1608 (2016).

Zeng, S. W., Baillargeat, D., Hod, H. P. & Yong, K. T. Nanomaterials enhanced surface plasmon resonance for biological and chemical sensing applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 3426–3452 (2014).

Xu, H. X., Bjerneld, E. J., Kall, M. & Borjesson, L. Spectroscopy of single hemoglobin molecules by surface enhanced Raman scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 4357–4360 (1999).

Lee, J. H., You, M. H., Kim, G. H. & Nam, J. M. Plasmonic nanosnowmen with a conductive junction as highly tunable nanoantenna structures and sensitive, quantitative and multiplexable surface-enhanced Raman scattering probes. Nano Lett. 14, 6217–6225 (2014).

Hao, E., Bailey, R. C., Schatz, G. C., Hupp, J. T. & Li, S. Synthesis and optical properties of “branched” gold nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 4, 327–330 (2004).

Shao, L. et al. Plasmonic properties of single multispiked gold nanostars: correlating modeling with experiments. Langmuir 28, 8979–8984 (2012).

Hao, F., Nehl, C. L., Hafner, J. H. & Peter, N. Plasmon resonances of a gold nanostar. Nano Lett. 7, 729–732 (2007).

Ziegler, J., Djiango, M., Vidal, C., Hrelescu, C. & Klar, T. A. Gold nanostars for random lasing enhancement. Optics Express 23, 15152–15159 (2015).

Jalani, G. & Cerruti, M. Nano graphene oxide-wrapped gold nanostars as ultrasensitive and stable SERS nanoprobes. Nanoscale 7, 9990–9997 (2015).

Anisha, G. et al. Bimetallic 3D nanostar dimers in ring cavities: recyclable and robust surface-enhanced Raman scattering substrates for signal setection from few molecules. ACS Nano 8, 7986–7994 (2014).

Zhang, X. Y. et al. Self-assembly of large-scale and ultrathin silver nanoplate films with tunable plasmon resonance properties. ACS Nano 5, 9082–9092 (2011).

Yang, S. et al. Electrochemically created highly surface roughened Ag nanoplate arrays for SERS biosensing applications. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater Opt. Electron Devices 2, 8350–8356 (2014).

Sun, Y. & Wiederrecht, G. P. Surfactantless synthesis of silver nanoplates and their application in SERS. Small 3, 1964–1975 (2007).

Li, R. Z. et al. Robust Ag nanoplate ink for flexible electronics packaging. Nanoscale 7, 7368–7377 (2015).

Zhang, X. Y., Zhang, T., Hu, A., Song, Y. J. & Duley, W. W. Controllable plasmonic antennas with ultra narrow bandwidth based on silver nano-flags. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 153118 (2012).

Lorenzo, L. R., Herrera, J. M., Juste, J. P., Puebla, R. A. & Marzan, L. M. Reshaping and LSPR tuning of Au nanostars in the presence of CTAB. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 11544–11549 (2011).

Xia, Y. N., Xiong, Y. J., Lim, B. & Skrabalak, S. E. Shape controlled synthesis of metal nanocrystals: simple chemistry meets complex physics? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 60–103 (2009).

Pieczonka, N. P. W. & Aroca, R. F. Single molecule analysis by surfaced-enhanced Raman scattering. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 946–954 (2008).

Camden, J. P. et al. Probing the structure of single-molecule surface-enhanced Raman scattering hot spots. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 12616–12617 (2008).

Zhu, S. Q. et al. Gold nanoparticle thin films fabricated by electrophoretic deposition method for highly sensitive SERS application. Nanoscale Research Letters 7, 613 (2012).

Martins, M. A. D. et al. Shifted-excitation Raman difference spectroscopy for in vitro and in vivo biological samples analysis. Optic. Express 1, 617–626 (2010).

Meyer, M. W., Lupoi, J. S. & Smith, E. A. Matrix effects in inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry: a review. Analytica Chimica Acta 706, 164–174 (2011).

Fales, A. M., Yuan, H. & Dinh, T. V. Silica-coated gold nanostars for combined surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) detection and singlet-oxygen generation: A potential nanoplatform for theranostics. Langmuir 27, 12186–12190 (2011).

Yuan, H. et al. Gold nanostars: surfactant-free synthesis, 3D modelling, and two-photon photoluminescence imaging. Nanotechnology 23, 075102(1–9) (2012).

Kelly, K. L., Coronado, E., Zhao, L. L. & Schatz, G. C. The optical properties of metal nanoparticles: the influence of size, shape, and dielectric environment. J. Phys. Chem. B 107, 668–677 (2003).

Sun, X., Dong, S. & Wang, E. Large‐scale synthesis of micrometer‐scale single‐crystalline Au plates of nanometer thickness by a wet‐chemical route. Angew. Chem. 116, 6520–6523 (2004).

Kwon, K. et al. Controlled synthesis of icosahedral gold nanoparticles and their surface-enhanced Raman scattering property. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 1161–1165 (2007).

Cheng, L. C. et al. Seedless, silver-induced synthesis of star-shaped gold/silver bimetallic nanoparticles as high efficiency photothermal therapy reagent. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 2244–2253 (2012).

Zhou, Y., Wang, C. Y., Zhu, Y. R. & Chen, Z. Y. A novel ultraviolet irradiation technique for shape-controlled synthesis of gold nanoparticles at room temperature. Chem. Mater. 11, 2310–2312 (1999).

Sau, T. K., Rogach, A. L., Döblinger, M. & Feldmann, J. One step high yield aqueous synthesis of size tunable multispiked gold nanoparticles. Small 7, 2188–2194 (2011).

Sau, T. K., Rogach, A. L., Jäckel, F., Klar, T. A. & Feldmann, J. Properties and applications of colloidal nonspherical noble metal nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 22, 1805–1825 (2010).

Su, Q. Q., Ma, X. Y., Dong, J., Jiang, C. Y. & Qian, W. P. A reproducible SERS substrate based on electrostatically assisted APTES-functionalized surface-assembly of gold nanostars. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 3, 1873–1879 (2011).

Zhu, S. Q. et al. Gold nanoparticle thin films fabricated by electrophoretic deposition method for highly sensitive SERS application. Nanoscale Research Letters 7, 613 (2012).

Zhang, Q. F., Large, N. & Wang, H. Gold nanoparticles with tipped surface structures as substrates for single-particle surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy: concave nanocubes, nanotrisoctahedra, and nanostars. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 17255–17267 (2014).

Li, Z. P. & Xu, H. X. Nanoantenna effect of surface-enhanced Raman scattering: managing light with plasmons at the nanometer scale. Advances in Physics: X 1, 492–521 (2016).

Ru, E. C. L., Blackie, E., Meyer, M. & Etchegoin, P. G. Surface enhanced Raman scattering enhancement factors: a comprehensive study. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 13794–13803 (2007).

Zhang, X.-Y. et al. Seeds triggered massive synthesis and multi-step room temperature post-processing of silver nanoink—application for paper electronics. RSC Adv. 7, 8–19 (2017).

Li, M.-D. et al. Clean Substrates Prepared by Chemical Adsorption of Iodide Followed by Electrochemical Oxidation for Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopic Study of Cell Membrane. Anal. Chem. 80, 5118–5125 (2008).

Taylor., C. E., Garvey, S. D. & Pemberton, J. E. Carbon Contamination at Silver Surfaces: Surface Preparation Procedures Evaluated by Raman Spectroscopy and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 68, 2401–2408 (1996).

Bermudez, V. M., Berry, A. D. & Kim, H. & Piqué A. Functionalization of Indium Tin Oxide. Langmuir 22, 11113–11125 (2006).

Zhang, T. et al. Plasmonic nanostructures for electronic designs of photovoltaic devices: plasmonic hot-carrier photovoltaic architectures and plasmonic electrode structures. Journal of Photonics for Energy 6, 042504 (2016).

Kamat, P. V. & Shanghavi, B. Interparticle electron transfer in metal/semiconductor composites picosecond dynamics of CdS-capped gold nanoclusters. J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 7675–7679 (1997).

Yun, C. S. et al. Nanometal surface energy transfer in optical rulers, breaking the FRET barrier. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 3115–3119 (2005).

Tovmachenko, O. G., Craf, C., Heuvel, D. J., Blaaderen, A. & Gerritsen, H. C. Fluorescence enhancement by metal-core/silica-shell nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 18, 91–95 (2006).

Camposeo, A. et al. Metal-enhanced near-infrared fluorescence by micropatterned gold nanocages. ACS Nano 9, 10047–10054 (2015).

Li, J. F. et al. Surface analysis using shell-isolated nanoparticleenhanced Raman spectroscopy. Nature Protocols 8, 52–65 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by MOST under Grant Number 2017YFA0205800, NSFC under grant numbers 61307066 and 61450110442, Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province under grant number BK20130630, Doctoral Fund of Ministry of Education of China under grant number 20130092120024, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and Graduate Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province under grant number KYLX_0126, Innovation fund of School of Electronic Science and Engineering, Southeast University under grant number 2242015KD006, Scientific Research Foundation of Graduate School of Southeast University YBJJ1513 and YBJJ1613.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F. Shan and X.-Y. Zhang designed and performed the experiments. T. Zhang funded the project and provided advice and helpful results discussion. X.-C. Fu, L.-J. Zhang, D. Su, S.-J. Wang and J.-Y. Wu participated in the experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript and discussed the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shan, F., Zhang, XY., Fu, XC. et al. Investigation of simultaneously existed Raman scattering enhancement and inhibiting fluorescence using surface modified gold nanostars as SERS probes. Sci Rep 7, 6813 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07311-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07311-8

This article is cited by

-

Glass-Based Nanobiosensor Immobilized with Oriented Antibody-Conjugated Gold Nanourchin for Targeted Detection of Breast Cancer Biomarker in Serum Using FT-NIR and SERS

Plasmonics (2023)

-

Non-invasive optical characterization and detection of CA 15–3 breast cancer biomarker in blood serum using monoclonal antibody-conjugated gold nanourchin and surface-enhanced Raman scattering

Lasers in Medical Science (2022)

-

Gap Plasmonics of Single Gold Nanoparticle Above a Gold Substrate Covered with Thin Gain Film

Plasmonics (2022)

-

Morphology-Directed Nanoscopic Energy Transfers in Plasmonic-Organic Hybrids

Journal of Applied Spectroscopy (2021)

-

Recent progress on nanostructure-based broadband absorbers and their solar energy thermal utilization

Frontiers of Chemical Science and Engineering (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.