Abstract

Lilium is a large genus that includes approximately 110 species distributed throughout cold and temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. The species-level phylogeny of Lilium remains unclear; previous studies have found universal markers but insufficient phylogenetic signals. In this study, we present the use of complete chloroplast genomes to explore the phylogeny of this genus. We sequenced nine Lilium chloroplast genomes and retrieved seven published chloroplast genomes for comparative and phylogenetic analyses. The genomes ranged from 151,655 bp to 153,235 bp in length and had a typical quadripartite structure with a conserved genome arrangement and moderate divergence. A comparison of sixteen Lilium chloroplast genomes revealed ten mutation hotspots. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for any two Lilium chloroplast genomes ranged from 8 to 1,178 and provided robust data for phylogeny. Except for some of the shortest internodes, phylogenetic relationships of the Lilium species inferred from the chloroplast genome obtained high support, indicating that chloroplast genome data will be useful to help resolve the deeper branches of phylogeny.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The genus Lilium, in the family Liliaceae, is economically and phylogenetically important and includes approximately 110 species distributed throughout the cold and temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, especially East Asia and North America1, 2, with eastern Asia and the Himalayas established as the center of diversity for this species. De Jong3 and Patterson & Givnish4 have described southwestern China and the Himalayas as the point of origin for the genus Lilium. Many Lilium species, ornamental cultivars and hybrids (such as Oriental hybrid, LA-hybrid, OT-hybrid, Asiatic hybrid, LO-hybrid, Longiflorum, and Aurelian & Trumpet), are cultivated for their esthetic value. In addition, both the flowers and bulbs are regularly consumed as both food and medicine in many parts of the world, particularly in Asia5. Presently, the “medicine food homology” values of Lilium plants have received considerable attention with respect to their great commercial prospects.

Nevertheless, many natural distribution areas of the wild lily are being adversely affected by both natural and human forces6, 7, and a growing number of Lilium species are on the verge of extinction (the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (http://www.iucnredlist.org)). Thus, programs to protect and preserve lily resources (especially rare lily species) are urgently needed. Species endemic to China—L. paradoxum Stearn, L. medogense S. Y. Liang, L. pinifolium L. J. Peng, L. saccatum S. Y. Liang, L. huidongense J. M. Xu, L. matangense J. M. Xu, L. stewartianum I. B. Balfour et W. W. Smith, L. habaense F. T. Wang et Tang, L. jinfushanense L. J. Peng et B. N. Wang, L. xanthellum F. T. Wang et Tang and L. fargesii Franch.—have been put on the China Species Red List8.

Lilium, which is taxonomically and phylogenetically regarded as an important clade of the core Liliales, appears to have evolved in the Himalayas approximately 12 million years ago, despite the lack of fossil records4, 9. Currently, the major phylogenetic clades of Lilium have been basically clear, and the updated system classifies the genus into seven sections primarily based on morphological taxonomy and molecular phylogenetic methods10,11,12,13,14,15. In the past two decades, the nuclear rDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS)11, 13,14,15 and several plastid genome regions have frequently been used in Lilium molecular systematics, including matK, rbcL, ndhF, and spacer regions of trnL-F, rpl32-trnL, trnH-psbA, or their combination. In addition, these studies have shown an incongruence between plastid and nuclear phylogenies4, 12, 16. A similar incongruence has been reported in recent studies of the genus Oryza 17, the tribe Arundinarieae18, the genera Medicago 19 and Ilex 20 and has been attributed to the use of markers with insufficient phylogenetic signals, incomplete lineage sorting, or complex evolutionary issues. Moreover, the selected loci unfortunately have not provided sufficient phylogenetic resolution at the species level for Lilium. For the conservation, utilization, and domestication of Lilium plants, more effective molecular markers are needed to identify Lilium species and evaluate the population genetics and breeding for the Lilium genus. DNA barcoding can be used to elucidate plant relationships at the species level; therefore, the identification of high-resolution molecular markers at the species level is critical to the success of DNA barcoding in plants21.

Chloroplast (cp) is the key organelle for photosynthesis and carbon fixation in green plants22, and therefore, their genomes could provide valuable information for taxonomic classification and the reconstruction of phylogeny because of sequence divergence among plant species and individuals23. Due to their maternal inheritance, very low recombination and haploidy, cp genomes are helpful for tracing source populations and phylogenetic studies of land plants for resolving complex evolutionary relationships24,25,26. Typical cp genomes in angiosperms have a generally conserved quadripartite circular structure with two copies of inverted repeat (IR) regions that are separated by a large single copy (LSC) region and a small single copy (SSC) region27, 28. These genomes with sizes in the range of 120–170 kb typically encode 120–130 genes.

The use of whole chloroplast genomes as a universal barcode and the existence of variable characters among the chloroplast genomes at the species level have recently been demonstrated, helping to overcome the previously low resolution in plant relationships17, 20,21,22,23, 29,30,31,32,33. With the rapid development of next-generation sequencing, it is now more convenient and relatively inexpensive to obtain cp genome sequences and extend gene-based phylogenetics to phylogenomics.

In this study, we present the complete chloroplast genomes of nine Lilium species through NGS sequencing and add seven species from GenBank34,35,36,37,38,39,40. We then test the feasibility of phylogeny reconstruction using the chloroplast genome. We further perform an analysis to gain insights into the overall evolutionary dynamics of chloroplast genomes in Lilium.

Results

Genome sequencing and assembly

Using the Illumina HiSeq 4000 system, nine Lilium taxa were sequenced to produce 3,719,304–11,167,835 paired-end raw reads (150 bp in average read length). Lilium cp genomes were de novo assembled using SPAdes 3.6.1. After these paired-end reads were screened through alignment with the chloroplast genome using Geneious V9, 47,505 to 988,478 cp genome reads were extracted with 46 X to 971 X coverage (Table 1). The four junction regions in each genome were validated by PCR-based sequencing according to Dong et al.41.

Complete chloroplast genomes of Lilium species

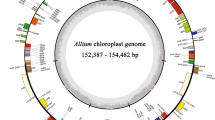

The nucleotide sequences of the 16 Lilium cp genomes range from 151,655 bp (L. bakerianum) to 153,235 bp (L. fargesii; Fig. 1, Table 2). The Chloroplast genomes assembled in single circular, double-stranded DNA sequences, displaying a typical quadripartite structure, consisting of a pair of IRs (26,394–26,990 bp) separated by the LSC (81,224–82,480 bp) and SSC (17,038–17,620 bp) regions. The overall GC content is 36.9–37.1%, indicating nearly identical levels among the 16 complete Lilium cp genomes. The Lilium cp genome contains 113 genes, including 79 protein coding genes, 30 tRNA genes, and 4 rRNA genes (Fig. 1, Table S1). All four rRNA genes are duplicated in the IR region. Fifteen distinct genes contain one intron, two of which contain two introns (clpP and ycf3). The rps12 gene is a trans-spliced gene with the 5′ end located in the LSC region and the duplicated 3′ end in the IR region, as has been reported previously in other plants.

Gene map of the 16 Lilium chloroplast genome. The genes inside and outside of the circle are transcribed in the clockwise and counterclockwise directions, respectively. Genes belonging to different functional groups are shown in different colors. The thick lines indicate the extent of the inverted repeats (IRa and IRb) that separate the genomes into small single copy (SSC) and large single copy (LSC) regions.

Simple Sequence Repeats (SSR) analysis of the Lilium cp genome

We used MISA to detect the SSR sites of all 16 chloroplast genomes. The number of SSRs in chloroplast genomes differed among the sixteen Lilium species, as shown in Table 2. The number of SSRs varied from 53 to 78. The most abundant were mononucleotide repeats, which accounted for approximately 56.38% of the total SSRs, followed by dinucleotides and tetranucleotides (Table S2). Hexanucleotides are very rare across the cp genomes.

In Lilium, all mononucleotides (100%) are composed of A/T, and a similar majority of dinucleotides (70.31%) are composed of A/T (Fig. 2). Our findings are comparable to previously reported findings that chloroplast genome SSRs are composed of polyadenine (polyA) or polythymine (polyT) repeats and rarely contained tandem guanine (G) or cytosine (C) repeats. Most of those SSRs are located in the LSC and SSC regions. In general, the SSRs of the sixteen Lilium species represent abundant variation and can be used in combination with nuclear SSRs developed in the genus for conservation or reintroduction, species biodiversity assessments and phylogenetic studies of Lilium in native or introduced areas.

Genome sequence divergence among Lilium species

We compared nucleotide diversity in the total, LSC, SSC, and IR regions of the cp genomes. The alignment revealed high sequence similarity across the Lilium cp genomes, suggesting that they are highly conserved. In total, 3,182 variable sites (2.03%), including 1,449 parsimony-informative sites in the total cp genomes were found (0.93%; Table 3). Among these regions, IR regions exhibite the least nucleotide diversity (0.00093) and SSC higher divergence (0.00839).

The p-distance and number of nucleotide substitutions were used to estimate divergence among the sixteen Lilium species. The p-distance among Lilium species ranges from 0.0001 to 0.0074, and the number of nucleotide substitutions was found to be 8 to 1,178 (Table S3). L. fargesii and L. longiflorum show the graest sequence divergence. L. sp. (from GenBank) exhibits only 8 nucleotide substitutions (L. tsingtauense), with the second lowest divergence being 63 nucleotide substitutions (L. hansonii).

Divergence of hotspot regions

Genome-wide comparative analyses among the sixteen Lilium species expected non-coding and SC regions to exhibit higher divergence levels than those of coding and IR regions, respectively (Fig. 3). Furthermore, to calculate the sequence divergence level, the nucleotide diversity (pi) value within 800 bp was calculated (Fig. 3). In the Lilium cp genome, these values variy from 0 to 0.02247. We identified 10 hotspot regions for genome divergence that could be utilized as potential markers to reconstruct the phylogeny and plant identification in this genus: trnS-trnG, trnE-trnT-psbD, trnF-ndhJ, psbE-petL, trnP-psaJ-rpl33, psbB-psbH, petD-rpoA, ndhF-rpl32-trnL, ycf1a, and ycf1b. Seven of these (trnS-trnG, trnE-trnT-psbD, trnF-ndhJ, psbE-petL, trnP-psaJ-rpl33, psbB-psbH, and petD-rpoA) are located in the LSC, and three (ndhF-rpl32-trnL, ycf1a, and ycf1b) in the SSC region. Only two markers (ycf1a and ycf1b) are in coding regions. Among these, the coding marker ycf1b shows the highest variability (Fig. 3, Table 4).

Phylogenetic analysis

In the present study, five datasets (whole complete cp genome sequences, LSC, SSC, IR and ten combined variable regions) from cp genomes of sixteen Lilium and four outgroups as well as Smilax china were used to perform phylogenetic analysis. Using MP, ML and MrBayes analyses, phylogenetic trees were constructed based on five datasets (Figs 4 and 5, Fig. S1). The topologies based on the three methods of analysis were highly concordant in each dataset, as well as with the results of Rønsted et al.41 and the phylogenetic trees had moderate to high support, except for the IR dataset, which received poor support. In addition, Fritillaria species or added Smilax china were used as the outgroup. The results showed that different outgroups could not influence the ingroup topology in our research (Figs 4 and 5, Fig. S1).

Phylogenetic relationships of the 16 Lilium species inferred from maximum parsimony (MP), maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian (BI) analyses of different data partitions. (A) Whole chloroplast genome. (B) LSC region. (C) IR region. (D) SSC region. Numbers above nodes are support values with MP bootstrap values on the left, ML bootstrap values in the middle, and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) values on the right.

Phylogeny of the 16 Lilium species constructed using 10 regions of highly variable sequences. Fritillaria was used as the outgroup. Numbers above nodes are support values with MP bootstrap values on the left, ML bootstrap values in the middle, and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) values on the right.

The sixteen Lilium species were grouped into two branches (Fig. 4). All the datasets indicated that two sect. Leucolirion 6b species, L. brownii and L. longiflorum, form a monophyletic group and then cluster with three sect. Martagon species, L. sp. (from GenBank), L. tsingtauense and L. hansonii as well as species of L. cernuum, L. lancifolium and L. davidii var. willmottiae, which belong to sect. Sinomartagon 6a. In the other branch, L. superbum belongs to sect. Pseudolirium is distributed in North America; the other seven Lilium species are native to Hengduan Mountains and the Himalayas and form another monophyletic clade.

Discussion

Chloroplast genome evolution in Lilium

In this study, nine new chloroplast genome sequences of Lilium were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq platform. The complete cp genomes range from 151,655 to 153,235 bp, which is within the range of cp genomes from other angiosperms42. The cp genomes of Lilium are highly conserved, with identical gene content and gene order and genomic structure comprising four parts. Such a low GC content has also been found in other angiosperm chloroplast genomes43.

Through a comparative analysis of Lilium cp genome sequences, we rapidly developed molecular markers such as single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs), and SSRs a type of 1–7 nucleotide unit tandem repeat sequence frequently observed in cp genomes, have been shown to have significant potential applications. SSRs are These markers are widely used in population genetics and breeding program studies44, 45 because of their high polymorphism even within species, due to slipped-strand mispairing on a single DNA strand during DNA replication46. In this study, 1,043 SSRs were identified in sixteen Lilium cp genomes. The most abundant are mononucleotide repeats, accounting for more than 56.38% of the total SSRs, followed by the di-, tri-, tetra-, and pentanucleotides. These new resources will be potentially useful for population studies in the Lilium genus, possibly in combination with other informative nuclear genome SSRs.

The nucleotide substitution rate is a central question in molecular evolution47. Based on the number and distribution of SNP and proportions of variability, the sequence divergence of the IR region is lower than that in LSC and SSC regions, also occurring in many previously reported plants30, 48. All pairwise sequence comparisons in our study reveal that DNA sequences evolve at different rates in different species. This result has also been found in other taxa49.

Because Lilium contains more than 100 species, its DNA barcoding and taxonomy are difficult to assess. The rbcL, matK, trnH-psbA, and ITS genes have been widely used to investigate taxonomy and DNA barcoding at the interspecific level (China Plant BOL Group 2014). In DNA barcoding or molecular phylogenetic studies of Lilium, these markers had extremely low discriminatory power11,12,13. The indel and SNP mutation events in the genome were not random but clustered as “hotspots.” Such mutational dynamics created the highly variable regions in the genome30. Therefore, based on our study, the largest sequence divergence regions are trnS-trnG, trnE-trnT-psbD, trnF-ndhJ, psbE-petL, trnP-psaJ-rpl33, psbB-psbH, petD-rpoA, ndhF-rpl32-trnL, ycf1a, and ycf1b. Regions ycf1a and ycf1b are particularly highly variable among Lilium, and they have been added as a core plant DNA barcode22. The trnE-trnT-psbD, trnS-trnG and ndhF-rpl32-trnL regions have been widely used for phylogenetic studies20, 50. Two rarely reported highly variable regions, psbB-psbH and petD-rpoA, present in the Lilium cp genome were identified in the present study.

Inferring the phylogeny with chloroplast phylogenomics in Lilium

Phylogenetic analyses based on complete plastid genome sequences have provided valuable insights into relationships among and within plant genera. Early studies have been conducted to position uncertain families in angiosperms, such as Amborellaceae51, Nymphaeaceae52, and Nelumbonaceae53. With the recent advent of NGS technology, chloroplast genomes can be sequenced quickly and cheaply, and they have been successfully used to address various phylogenetic questions at the family and even at the species level54,55,56.

In this study, different datasets produced similar topological structures, except the IR dataset, possibly because IR is more conserved and provides fewer information sites than those found in SC regions (Table S2). All trees based on the datasets (except the IR dataset) were not only coincident with the previous phylogenetic studies based on ITS sequences15, 16 or the commonly used chloroplast genes such as matK, rbcL, atpB and atpF-H 4, 12, 57 but also had higher bootstrap values and resolution, especially at low classification levels. For example, the Martagon clade, including L. sp., L. tsingtauense and L. hansonii, received a higher robust support in the dataset (cp genome, LSC, SSC and ten variable regions) than the clade based on other markers (Figs 4 and 5; Fig. S1). Furthermore, species of L. sp. and L. tsingtauense were found to form a robustly supported clade ([ML] Bootstrap = 99, [MP] Bootstrap = 100 and PP = 1), suggesting that the two species are likely the same. Phylogenetic trees based on the cp genome, LSC, SSC and ten variable regions datasets support (with low support) that L. distichum (from GenBank) form a clade with the clade of L. bakerianum and L. nepalense var. ochraceum or the clade of L. fargesii and L. duchartrei (Figs 4 and 5; Fig. S1). However, L. distichum possesses a whorled leaf and is attributed to the sect. Martagon. Therefore, the species identification of L. distichum from GenBank may be inaccurate. However, evolutionary relationships and divisions within species/section need further investigation.

This study used the cp genome data to infer the phylogenetic relationships in Lilium, providing genome-scale support. The cp genome is expected to be useful in resolving the deeper branches of the phylogeny as more whole-genome sequences become available in Lilium.

Methods

Plant material and DNA extraction

Fresh leaves of nine Lilium species were sampled (Table 5). Specimens were deposited in the herbarium of the Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences (PE) (Table 5). Total genomic DNA was extracted using a plant genome extraction kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). Subsequently, DNA concentration was measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, America).

Genome sequencing, assembly and annotation

DNA was sheared to construct a 400 bp (insert size) paired-end library in accordance with the Illumina HiSeq 4000 standard protocol. The paired-end reads were qualitatively assessed and assembled using SPAdes 3.6.158. The gaps were filled by PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing. Sanger sequence reads were proofread and assembled with Sequencher 4.10 (http://www.genecodes.com).

All genes encoding proteins, transfer RNAs (tRNAs), and ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) were annotated on Lilium. Plastomes were annotated using Dual Organellar Genome Annotator (DOGMA) software and the tRNAscan-SE 1.21 program59, 60. Initial annotation, putative starts, stops, and intron positions were determined by comparison with homologous genes in other Lilium cp genomes.

Microsatellite analysis

Perl script MISA61 was used to detect microsatellites (mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotide repeats) with the following thresholds (unit size, min repeats): ten repeat units for mononucleotide SSRs, five repeat units for dinucleotide SSRs, four repeat units for trinucleotide SSRs, and three repeat units each for tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotide SSRs.

Molecular marker identification and sequence divergence analysis

The sequences were first aligned using MAFFT v762 and then manually adjusted using BioEdit software. Subsequently, a sliding window analysis was conducted to evaluate the nucleotide variability (Pi) of the cp genome using DnaSP version 5.1 software63. The step size was set to 200 base pairs, and the window length was set to 600 base pairs.

Variable and parsimony-informative base sites across the complete cp genomes and the large single copy (LSC), small single copy (SSC), and inverted repeat (IR) regions of the six cp genomes were calculated using MEGA 6.0 software64. The p-distance among Lilium cp genomes was calculated to evaluate the divergence of Lilium species using MEGA software.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic trees were constructed by maximum parsimony (MP), maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian analysis (BI) methods using the entire cp genome, LSC, SSC, IR regions and combining ten variable regions. The lengths of all alignment matrices of these datasets are shown in Table 3. In all phylogenetic analyses, Fritillaria or Smilax china were used as the outgroup (Figs 4 and 5, Fig. S1).

MP analyses were conducted using PAUP v4b1065 with heuristic searches with the ‘MulTrees’ option followed by tree bisection–reconnection (TBR) branch swapping. Branch support was assessed with 1,000 random addition replicates. All characters were unordered and were accorded equal weight, with gaps being treated as missing data. The best-fit substitution models were selected by running ModelTest 3.766 under the Akaike information criterion (AIC). ML analyses were performed using RAxML-HPC BlackBox v.8.1.24 at the CIPRES Science Gateway website67, 68. For ML analyses, the best-fit models, general time reversible (GTR) + G, were used in all analyses, as suggested with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. BI was performed with MrBayes 3.269. Two independent Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains were run, each with three heated and one cold chain for 50 million generations. Each chain started with a random tree, default priors and sampling trees every 1,000 generations, with the first 25% discarded as burn-in. Stationarity was considered reached when the average standard deviation of split frequencies remained below 0.01.

References

Liang, S. J., Tamura, M. Flora of China, Vol 24. Lilium. 118–152 (Science Press, Beijing, and Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis., 2000).

McRae, E. A. Lily species. Lilies. 105–204 (Timber Press, Portland, 1998).

De Jong, P. C. Some notes on the evolution of lilies. Lily Year Book. 27, 23–28 (The North American Lily Society Press, 1974).

Patterson, T. B. & Givnish, T. J. Phylogeny, concerted convergence, and phylogenetic niche conservatism in the core Liliales: insights from rbcL and ndhF sequence data. Evolution. 56(2), 233–52 (2002).

Munafo, J. P. Jr. & Gianfagna, T. J. Chemistry and biological activity of steroidal glycosides from the Lilium genus. Nat. Prod. Rep. 32(3), 454–477 (2015).

Long, Y. Y. & Zhang, J. Z. The conservation and utilization of lily plant resources. Journal of Plant Resources & Environment. 7(1), 40–44 (1998).

Du, Y. P. et al. Investigation and evaluation of the genus Lilium resources native to China. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 61(2), 395–412 (2014).

Wang, S. & Xie, Y. China species red list. Vol. 1. (Higher Education Press, Beijing, 2004).

Gao, Y. D., Harris, A. J., & He, X. J. Morphological and ecological divergence of Lilium and Nomocharis within the Hengduan Mountains and Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau may result from habitat specialization and hybridization. BMC Evol. Biol. (1), 1–21 (2015).

Comber, H. F. A new classification of the genus Lilium. Lily Year Book. (RHS Press, London, 1974).

Nishikawa, T. et al. A molecular phylogeny of Lilium in the internal transcribed spacer region of nuclear ribosomal DNA. J. Mol. Evol. 49(2), 238–249 (1999).

Hayashi, K. & Kawano, S. Molecular systematics of Lilium and allied genera (Liliaceae): phylogenetic relationships among Lilium and related genera based on the rbcL and matK gene sequence data. Plant Spec. Biol. 15, 73–93 (2000).

Nishikawa, T. et al. Phylogenetic Analysis of section Sinomartagon in genus Lilium using sequences of the internal transcribed spacer region in nuclear ribosomal DNA. Breeding Sci. 51(1), 39–46 (2001).

Rešetnik, I. et al. Molecular phylogeny and systematics of the Lilium carniolicum group (Liliaceae) based on nuclear ITS sequences. Plant Syst. Evol. 265(1), 45–58 (2007).

Du, Y. P. et al. Molecular phylogeny and genetic variation in the genus Lilium native to China based on the internal transcribed spacer sequences of nuclear ribosomal DNA. J. Plant Res. 127(2), 249–263 (2014).

Gao, Y. D. et al. Evolutionary events in Lilium (including Nomocharis, Liliaceae) are temporally correlated with orogenies of the Q–T plateau and the Hengduan Mountains. Mol. Phylogenet. Evo. 68(3), 443–460 (2013).

Wambugu, P. W. et al. Relationships of wild and domesticated rices (Oryza AA genome species) based upon whole chloroplast genome sequences. Sci. Rep. 5 (2015).

Yi, T. S., Jin, G. H. & Wen, J. Chloroplast capture and intra-and inter-continental biogeographic diversification in the Asian–New World disjunct plant genus Osmorhiza (Apiaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 85, 10–21 (2015).

de Sousa, F., Bertrand, Y. J. K. & Pfeil, B. E. Patterns of phylogenetic incongruence in Medicago found among six loci. Plant Syst. Evol. 1–21 (2016).

Yao, X. et al. Chloroplast genome structure in Ilex (Aquifoliaceae). Sci. Rep. 6 (2016).

Dong, W. et al. ycf1, the most promising plastid DNA barcode of land plants. Sci. Rep. 5 (2015).

Douglas, S. E. Plastid evolution: origins, diversity, trends. Curr. Opin. Genet. De. 8(6), 655–661 (1998).

Huang, H. et al. Thirteen Camellia chloroplast genome sequences determined by high-throughput sequencing: genome structure and phylogenetic relationships. BMC Evol. Boil. 14(1), 1 (2014).

Yang, J. B. et al. Comparative chloroplast genomes of Camellia species. PLoS ONE. 8, e73053 (2013).

Lei, W. et al. Intraspecific and heteroplasmic variations, gene losses and inversions in the chloroplast genome of Astragalus membranaceus. Sci. Rep. 6 (2016).

Choi, K. S. et al. The Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequences of Three Veroniceae Species (Plantaginaceae): Comparative Analysis and Highly Divergent Regions. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 662 (2016).

Jansen, R. K. et al. Methods for obtaining and analyzing whole chloroplast genome sequences. Method Enzymol. 395, 348–384 (2005).

Jansen, R. K. & Ruhlman, T. A. Plastid Genomes of Seed Plants. (Springer Press, Berlin, 2012).

Shaw, J. et al. Comparison of whole chloroplast genome sequences to choose noncoding regions for phylogenetic studies in angiosperms: the tortoise and the hare III. Am. J. Bot. 94(3), 275–288 (2007).

Dong, W. et al. Highly variable chloroplast markers for evaluating plant phylogeny at low taxonomic levels and for DNA barcoding. PLoS ONE. 7, e35071, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035071 (2012).

Dong, W. et al. A chloroplast genomic strategy for designing taxon specific DNA mini-barcodes: a case study on ginsengs. BMC Genet. 15, 138 (2014).

Zhao, Y. B. et al. The complete chloroplast genome provides insight into the evolution and polymorphism of Panax ginseng. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 696 (2015).

Zhang, Y. J. et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequences of five Epimedium species: lights into phylogenetic and taxonomic analyses. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 696 (2016).

Kim, J. S. & Kim, J. H. Comparative genome analysis and phylogenetic relationship of order Liliales insight from the complete plastid genome sequences of two lilies (Lilium longiflorum and Alstroemeria aurea). PLoS ONE. 8(6), e68180 (2013).

Lee, S. C. et al. The complete chloroplast genomes of Lilium tsingtauense Gilg (Liliaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 1(1), 336–337 (2016).

Kim, K. et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Lilium hansonii Leichtlin ex DDT Moore. Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 27(5), 3678–3679 (2016).

Hwang, Y. J. et al. The complete chloroplast genome of Lilium distichum Nakai (Liliaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 27(6), 4633–4634 (2016).

Bi, Y. et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Lilium fargesii (Lilium, Liliaceae). Conserv. Genet. Resour. 8(4), 419–422 (2016).

Du, Y. P. et al. The complete chloroplast genome of Lilium cernuum: genome structure and evolution. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 8(4), 375–378 (2016).

Zhang, Q. et al. The complete chloroplast genome of Lilium taliense, an endangered species endemic to China. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 1–3 (2016).

Rønsted, N. et al. Molecular phylogenetic evidence for the monophyly of Fritillaria and Lilium (Liliaceae; Liliales) and the infrageneric classification of Fritillaria. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 35(3), 509–527 (2005).

Dong, W. et al. Sequencing angiosperm plastid genomes made easy: A complete set of universal primers and a case study on the phylogeny of Saxifragales. Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 989–997 (2013).

Do, H. D., Kim, J. S. & Kim, J. H. Comparative genomics of four Liliales families inferred from the complete chloroplast genome sequence of Veratrum patulum O. Loes. (Melanthiaceae). Gene. 530(2), 229–35 (2013).

Perdereau, A. et al. Plastid genome sequencing reveals biogeographical structure and extensive population genetic variation in wild populations of Phalaris arundinacea L. in north‐western Europe. G.C.B. Bioenergy (2016).

Tong, W., Kim, T. S. & Park, Y. J. Rice chloroplast genome variation architecture and phylogenetic dissection in diverse Oryza species assessed by whole-genome resequencing. Rice. 9, 57 (2016).

Borsch, T. & Quandt, D. Mutational dynamics and phylogenetic utility of noncoding chloroplast DNA. Plant Syst. Evol. 282, 169–199 (2009).

Gaut, B. et al. The Patterns and causes of variation in plant nucleotide substitution rates. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. S. 42, 245–266 (2011).

Song, Y. et al. Comparative analysis of complete chloroplast genome sequences of two tropical trees Machilus yunnanensis and Machilus balansae in the family Lauraceae. Front. Plant Sci. 6 (2015).

Smith, S. A. & Donoghue, M. J. Rates of molecular evolution are linked to life history in flowering plants. Science. 322, 86–89 (2008).

Shaw, J. et al. The tortoise and the hare II: Relative utility of 21 noncoding chloroplast DNA sequences for phylogenetic analysis. Am. J. Bot. 92, 142–166 (2005).

Goremykin, V. V. et al. Analysis of the Amborella trichopoda chloroplast genome sequence suggests that amborella is not a basal angiosperm. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 1499–1505 (2003).

Goremykin, V. V. et al. The chloroplast genome of Nymphaea alba: whole-genome analyses and the problem of identifying the most basal angiosperm. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 1445–1454 (2004).

Xue, J. H. et al. Nelumbonaceae: Systematic position and species diversification revealed by the complete chloroplast genome. J. Syst. Evol. 50, 477–487 (2012).

Bayly, M. J. et al. Chloroplast genome analysis of Australian eucalypts - Eucalyptus, Corymbia, Angophora, Allosyncarpia and Stockwellia (Myrtaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 69(69), 704–716 (2013).

Henriquez, C. L. et al. Phylogenomics of the plant family Araceae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 75(1), 91–102 (2014).

Jose, C. C. et al. A Phylogenetic Analysis of 34 chloroplast genomes elucidates the relationships between wild and domestic species within the genus. Citrus. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 32(8), 2015–35 (2015).

Kim, J. S. et al. Familial relationships of the monocot order Liliales based on a molecular phylogenetic analysis using four plastid loci: matK, rbcL, atpB, and atpF-H. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 172(1), 5–21 (2013).

Bankevich, A. et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19, 455–477 (2012).

Wyman, S. K., Jansen, R. K. & Boore, J. L. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics. 20, 3252–3255 (2004).

Schattner, P., Brooks, A. N. & Lowe, T. M. The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 33, 686–689 (2005).

Thiel, T. et al. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 106(3), 411–22 (2003).

Katoh, K. et al. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 30, 3059–3066 (2002).

Librado, P. & Rozas, J. Dnasp v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 25(11), 1451–2 (2009).

Tamura, K. et al. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30(12), 2725–2729 (2013).

Swofford, D. L. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods). Version 4.0b10. Mccarthy (2002).

Posada, D. & Crandall, K. A. Modeltest: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 14(9), 817–818 (1998).

Stamatakis, A., Hoover, P. & Rougemont, J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst. Biol. 57(1), 758–771 (2008).

Miller, M., Pfeiffer, W. & Schwartz, T. Creating the CIPRES science gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. 14, 1–8 (2010).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Boil. 61(3), 539–542 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 31601781), the National High Technology Research and Development Program 863 (2013AA102706) and Natural Science Foundation of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences (QNJJ201619).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.P.D. and X.H.Z. conceived the experiments, Y.P.D., M.F.Z. and X.Q.C. collected the samples, Y.P.D. and J.X. conducted the experiments, Y.P.D., Y.B. and F.P.Y. analyzed the results, Y.P.D. and Y.B. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, Yp., Bi, Y., Yang, Fp. et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of Lilium: insights into evolutionary dynamics and phylogenetic analyses. Sci Rep 7, 5751 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06210-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06210-2

This article is cited by

-

Comparative and phylogenetic analysis of the complete chloroplast genomes of ten Pittosporum species from East Asia

Functional & Integrative Genomics (2024)

-

Genetic diversity of Lilium candidum natural populations in Türkiye evaluated with ISSR and M13-tailed SSR markers

Plant Systematics and Evolution (2024)

-

Comparison of plastid genomes and ITS of two sister species in Gentiana and a discussion on potential threats for the endangered species from hybridization

BMC Plant Biology (2023)

-

The complete chloroplast genome of critically endangered Chimonobambusa hirtinoda (Poaceae: Chimonobambusa) and phylogenetic analysis

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Comparative analysis of complete chloroplast genome of ethnodrug Aconitum episcopale and insight into its phylogenetic relationships

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.