Abstract

Tripneustes is one of the most abundant and ecologically significant tropical echinoids. Highly valued for its gonads, wild populations of Tripneustes are commercially exploited and cultivated stocks are a prime target for the fisheries and aquaculture industry. Here we examine Tripneustes from the Kermadec Islands, a remote chain of volcanic islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean that mark the boundary of the genus’ range, by combining morphological and genetic analyses, using two mitochondrial (COI and the Control Region), and one nuclear (bindin) marker. We show that Kermadec Tripneustes is a new species of Tripneustes. We provide a full description of this species and present an updated phylogeny of the genus. This new species, Tripneustes kermadecensis n. sp., is characterized by having ambulacral primary tubercles occurring on every fourth plate ambitally, flattened test with large peristome, one to two occluded plates for every four ambulacral plates, and complete primary series of interambulacral tubercles from peristome to apex. It appears to have split early from the main Tripneustes stock, predating even the split of the Atlantic Tripneustes lineage. Its distinction from the common T. gratilla and potential vulnerability as an isolated endemic species calls for special attention in terms of conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The upsurge of molecular genetic data being generated over the past two decades has facilitated major advances in our understanding of speciation and biogeography across the tree of life. In particular, data from widely distributed genera and species can (1) provide independent evidence for genetic boundaries between cryptic species, (2) facilitate estimations of divergence times, (3) depict species divergence patterns through phylogenetic reconstructions, and (4) allow the examination of the geography of speciation1. Being widely distributed, easily accessible for sampling, and intensely studied since the 19th century, tropical sea urchin species are prime model taxa for the study of speciation and biogeography in the marine environment2,3,4.

Sea urchins of the genus Tripneustes are some of the most abundant and common circumtropical echinoids5. The genus consists of several largely allopatric species that vary in their levels of molecular and morphological divergence. Of those, Tripneustes gratilla (Linnaeus, 1758) is the most widespread, ranging from the Western Indian Ocean to the Eastern Pacific6. Apart from its role as an ecological keystone species in many tropical regions7, T. gratilla is unique in being one of the most commercially valued echinoid species to date and is a prime target for the fisheries and aquaculture industry8. In some localities, such as Oahu Island in Hawaii, T. gratilla are also being propagated as agents of environmental control to regulate the expansion of invasive alien seaweeds (http://dlnr.hawaii.gov/ais/invasivealgae/urchn-hatchery). At present, T. gratilla is being cultured at numerous locations throughout the species range8,9,10,11,12. Consequently, native populations are under growing pressure from cultivated fishery stocks and face the risk of being obliterated by either intentional release (e.g., as agents for ecological control) or accidental leakage from near shore facilities. This risk is particularly eminent for small endemic populations and species that are difficult to recognize morphologically.

A recent study, combining molecular genetics (mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences), morphological, fossil, and ecological evidence demonstrated that the Red Sea (RS) Tripneustes is a distinct clade, endemic to the RS13. This clade was likely formed at a time when gene flow between the RS Tripneustes and the wider Indian Ocean population was constricted. Considering the large morphological variability observed for Tripneustes across its vast range, it seems probable that the genus may contain additional highly localized endemic species, particularly around the periphery of its range.

For Tripneustes, the Kermadec Islands represent a remote area close to the southern Pacific boundary of the genus’ range. This chain of volcanic islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean is located ca. 1,000 km northeast of New Zealand and stretching for 2,600 km towards Tonga (Fig. 1). The shallow marine communities of the Kermadec Islands comprise a mixture of tropical, subtropical, and temperate species. Although several endemic fishes and marine invertebrates have been described14, the majority of shallow reef marine species found at the Kermadec Islands have broader New Zealand, Australasian, and even Indo-Pacific wide distributions14,15,16.

Map of the southeastern Indian Ocean and southwestern Pacific showing the location of the Kermadec Islands. Inset shows map of Raoul Island. Stars indicate sample collection localities of Tripneustes kermadecensis n. sp. The map is based on the Wikimedia Commons public domain map file BlankMap-World6.svg (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BlankMap-World6.svg) and edited using the cross-platform geographic information system QGIS v. 2.8.2 (Quantum GIS Development Team (2016). Quantum GIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. http://qgis.osgeo.org).

Previous studies have identified the Kermadec Tripneustes as T. gratilla (Linnaeus, 1758) (under the name Tripneustes variegatus)17,18,19,20,21. Although several studies on the phylogeography of Tripneustes have now been published, covering most of this genus’ presumed range13, 22, 23, only a single study24 so far has utilized DNA sequence data on Tripneustes from the Kermadec Islands. Based on the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COI) gene the latter authors found that seven individuals of Tripneustes sampled at the Kermadec Islands were represented by a single haplotype that is shared by most other Tripneustes populations in the east Indian and Pacific oceans. Consequently, they identified the Kermadec Tripneustes as the common Indo-Pacific T. gratilla24.

Here we re-examine Kermadec Tripneustes by combining novel genetic data (mitochondrial and nuclear) and the first in-depth morphological analyses of Kermadec Tripneustes to resolve the taxonomic status and reconstruct the phylogeny of Tripneustes from this remote location. We then use these data to explore Tripneustes evolutionary history.

Results

Morphological analyses

Pedicellarial characters often are useful for species differentiation in regular echinoids and Mortensen made ample use of them in his monograph series6. In the present case, however, pedicellariae offer few clues to the placement of the Kermadec Tripneustes population (Fig. 2). In all currently accepted Tripneustes species ophiocephalous and globiferous pedicellariae are highly similar and only tridentate pedicellariae show consistent morphological differences according to Mortensen25. The latter, however, appear not to be developed in the Kermadec population, as we were unable to find a single example in any of the specimens examined (a common phenomenon for pedicellariae, see review of Coppard et al.26). Fortunately, however, gross morphology, tuberculation and ambulacral plating offer good evidence for the placement of this population (Figs 3 and 4). Tripneustes from the Kermadec Islands have a very similar appearance to Caribbean T. ventricosus in life, but can be consistently differentiated from them by the morphological characters outlined below. Red Sea Tripneustes (T. g. elatensis) is the best match in terms of corona shape, but differs strongly in tuberculation pattern and ambulacral plating (compare13). Exceptionally large specimens of the East Pacific T. depressus can also have a similarly flattened shape, but usually (ref. 27: p. 375, 584; ref. 25: p. 499) T. depressus is high and swollen. Like T. ventricosus it further differs from Kermadec Tripneustes by its dense aboral tuberculation. T. gratilla gratilla from the Indian Ocean and the Coral Triangle shows strikingly different color and spine posture patterns in addition to differing corona shape and ambulacral tuberculation. Based on their morphological characters (Table 1), Tripneustes from the Kermadec Islands thus clearly belong to a novel, yet undescribed species.

External appendages of Tripneustes kermadecensis n. sp. Globiferous (A–E) and ophicephalous (F–J) pedicellariae in lateral (B,G), external (C,H), and internal views (D,E,I,J); (K–M): secondary spine with details of surface sculpture close to base (K) and close to tip (L). All from paratype NHMW-Geo 2017/0016/0001; (A,E–H,J) derive from the aboral side of the animal, (B–D,I,K–M) from the oral side.

Ambital ambulacral plating of Tripneustes species. (A) Tripneustes gratilla gratilla (TD = 90.7 mm; Phatthaya, Thailand; NHMW-Geo 2011/0352/0003); (B) Tripneustes gratilla elatensis (TD ~95 mm; Ras Abusoma, Safaga, Egypt; NHMW-Geo 2008z0004/0012); (C) Tripneustes kermadecensis n. sp. (TD = 94.5 mm; Meyer Islands, New Zealand; holotype AIM MA73563); (D) Tripneustes ventricosus (TD ~100 mm; Roatan Island, Honduras; NHMW-Geo 2008z0167/0016). Plates occluded from perradial suture highlighted in red.

Molecular genetic analysis

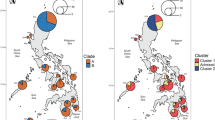

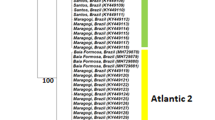

Bayesian Inference (BI) and Maximum Likelihood (ML) analyses produced congruent phylogenies for all clades and subclades in all datasets used and thus only BI inferred topologies are presented supplemented by the corresponding bootstrap values of the ML analysis and posterior probabilities support values of the BI analysis. Both mitochondrial markers; a portion of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene and a region located adjacent to the control region (COI and CR, respectively), show strong support for the monophyly of Kermadec Tripneustes (Figs 5–7 and Supplementary Fig. S1). Rooted with L. variegatus, the COI tree resolves the Kermadec clade as a sister group to all other known Tripneustes including the Atlantic T. ventricosus (Fig. 5). It thus suggests that the Kermadec lineage diverged early from the other Tripneustes species. Phylogenetic inference based on COI data alone show no structure in regards to the other IWP Tripneustes (the Red Sea T. g. elatensis, T. depressus and T. g. gratilla). Phylogenies based on the novel CR marker are congruent with the results obtained from COI (Fig. 6). Analysis of the CR returned two distinct IWP Tripneustes clades: clade A comprising solely of Kermadec Tripneustes, and clade B containing both T. g. elatensis and T. g. gratilla (Fig. 6). The mitochondrial diversity of Tripneustes was further explored by displaying the distributional patterns of the COI haplotypes through a Median joining haplotype network (Fig. 7). Similar to the topologies of the trees, the COI network shows three distinct clusters of haplotypes: (1) An Indo-Pacific cluster that includes T. g. elatensis, T. depressus and T. g. gratilla; (2) an Atlantic cluster comprising of T. ventricosus haplotypes; and (3) a cluster including only Kermadec Tripneustes (Fig. 7), none of the Kermadec samples sharing haplotypes with any of the other Tripneustes species.

Phylogenetic tree reconstruction of Tripneustes COI sequences. The BI tree is based on 44 haplotypes, 531 bp long, representing all extant species of Tripneustes and is rooted with Lytechinus variegatus (not shown). Supporting values (>0.9 posterior probabilities and >60% ML bootstrap values) are shown above the nodes. The colors of the specimen labels correspond to: Dark green – T. g. gratilla, Red – T. g. elatensis, Light green – T. depressus, Blue – T. ventricosus, and Orange – T. kermadecensis n. sp. Details on the sequences used for this tree are given in the Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Phylogenetic tree reconstruction of Tripneustes control region (CR) sequences. The BI tree is based on 19 unique haplotypes, 446 bp long, representing T. kermadecensis n. sp., T. g. elatensis and T. g. gratilla, and is rooted on Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus and Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis (GenBank accession numbers KC490911, EU054306 and NC009940, respectively). Color code as in Fig. 5. Supporting values (>0.9 posterior probabilities and >60% ML bootstrap values) are shown above the nodes. Clades A (comprising T. kermadecensis n. sp.), and B (comprising both T. g. gratilla and T. g. elatensis) are discussed in the text. Details on the sequences used for this tree are given in the Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Tripneustes COI Median-joining haplotype network. The network comprises 339 sequences, 448 bp long, generated during the current study as well as comparable Tripneustes COI sequences available from GenBank (for details see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Color code as in Fig. 5. Bars indicate the number of substitutions between nodes. The frequency of each haplotype is indicated by size of the circles (see key, top right).

In regards to Kermadec Tripneustes, results of the nuclear bindin analyses were similar to the results inferred from the mitochondrial markers. The resulting nuclear bindin tree recovered Kermadec Tripneustes as a strongly supported clade (Fig. 8). The tree also shows strong support for the monophyly of T. ventricosus and T. g. elatensis in contrast to T. depressus which is nested within one of the T. g. gratilla clades, and demonstrates the polyphyletic nature of T. g. gratilla showing a distinct split into several potential lineages in our analysis. Finally, a concatenated analysis using both mitochondrial and nuclear markers, recovered all major Tripneustes clades (i.e., T. g. gratilla, T. g. elatensis and T. kermadecensis n. sp.) with strong nodal support (Fig. 9), reflecting the monophyly of T. kermadecensis n. sp.

Phylogenetic tree reconstruction of Tripneustes bindin sequences. (A) Unrooted BI tree of 1256 bp long Tripneustes bindin sequences including exons 1 and 2 (excluding the glycine-rich repeat in exon 1; see main text for details) and parts of the intron (excluding the 169 bp region identified as transposon, respectively inverted repeat; see main text for details). The tree reconstruction is based on 54 unique haplotypes representing all extant species of Tripneustes. Supporting values (>0.9 posterior probabilities and >60% ML bootstrap values) are shown above the nodes. Color code as in Fig. 5. T. g. gratilla clades (A–C) are discussed in the text. Details on the sequences used for this tree are given in the Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. (B) Unique sequence features mapped on the bindin tree topology (position of root inferred from COI tree in Fig. 5). Numbers above branches represent number of gylcine rich repeats, names below branches provide information on the nature of insert at the 5′ end of the bindin intron (see text for details). Note that the transposon DNA-1-2_SP is inserted in normal orientation in T. g. gratilla clades A and B, but as reverse complement in T. ventricosus and T. g. gratilla clade C.

Phylogenetic tree reconstruction of concatenated Tripneustes sequences. The mid-point rooted BI tree reconstruction is based on 19 unique haplotypes, 2828 bp long, representing T. kermadecensis n. sp., T. g. elatensis and T. g. gratilla. Sequences were concatenated from alignable segments of the mitochondrial markers (COI and CR) as well as the nuclear marker bindin (including exons 1, 2 and the intron). Color code as in Fig. 5. Supporting values (>0.9 posterior probabilities and >60% ML bootstrap values) are shown near the nodes. Details on the sequences used for this tree are given in the Supplementary Table S1.

Based on the bindin dataset, sequence divergence within the Kermadec Tripneustes clade was low (0.4% mean K2P divergence), similar to the divergence within the Atlantic T. ventricosus, the RS T. g. elatensis and T. g. gratilla clade A (Table 2). In contrast, interspecific divergence (K2P) between Kermadec Tripneustes and the other Tripneustes clades was high and ranged from 3.1% to 4.0% showing 4.0% divergence from T. ventricosus, 3.1% divergence from T. g. elatensis, and 3.2–4.0% divergence from the other IWP T. g. gratilla clades (Table 2).

Unique sequence features

Alignment comparisons of bindin sequences from Kermadec Tripneustes with the other Tripneustes species revealed several indel regions that are unique to Kermadec Tripneustes and may provide an independent phylogenetic signal. As previously reported by Bronstein et al.13, the first bindin exon of Tripneustes includes a glycine-rich repeat region with similar glycine-rich motifs also reported from bindin of other camarodonts23. RS Tripneustes are unique in being the only Tripneustes bearing four copies of this repeat, only two copies are present in T. ventricosus and three in all other Tripneustes including T. g. gratilla, T. depressus and Kermadec Tripneustes. Consequently, this feature distinguishes the Kermadec Tripneustes from both T. g. elatensis and T. ventricosus (but not from T. g. gratilla or T. depressus) (Supplementary Fig. S2a).

A second feature, present only in the Kermadec Tripneustes, is located at the 5′-end of the bindin intron. In T. g. gratilla and T. ventricosus this 148 bp long region was found to be highly similar to a transposon named DNA-1-2_SP (Bronstein et al.13; first discovered in Strongylocentrotus purpuratus by Bao and Jurka28. In RS T. g. elatensis, in contrast, a highly divergent sequence comprising an inverted 169 bp long repeat is present at the same position (see ref. 13 for details). Samples from Kermadec Tripneustes are unique in possessing neither the 148 bp transposon, nor the 169 bp inverted repeat and this observation was consistent in all of the samples analyzed (Supplementary Fig. S2b). All identified unique sequence features were excluded from the phylogenetic analyses.

Methods

Study area and sample collection

Specimens of Tripneustes were hand collected while scuba diving at several locations throughout the Kermadec Islands, New Zealand, at depths of 3 to 25 meters (Fig. 1). Tissue samples (tube feet and spine muscles) from each sampled specimen were fixed and preserved in 96% molecular grade EtOH and the remaining whole specimen was formaldehyde fixed and preserved in 70% EtOH. Tables S1 and S2 give an overview of all novel samples and lists sample names, collection locations, and GenBank accession numbers, as well as data sources for sequences derived from GenBank. Specimens have been collected under permit DOCDM-737382 issued by the New Zealand Department of Conservation (Authorisation number: 47976-MAR) to the Auckland Museum Trust Board.

Molecular genetic analysis

Two DNA marker sequences were initially analyzed: the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene (COI) and the nuclear bindin gene (partial sequences of two exons and the intervening intron). Zigler and Lessios23 reported no evidence of diversifying selection for bindin in Tripneustes, asserting its suitability as a phylogenetic marker for this group. Following the results obtained from the first two markers and the arising contradiction to previously published COI data, we analyzed a longer stretch of the COI gene and, in addition, added a novel marker sequence, for which we recently developed primers located adjacent to the control region (CR) (Bronstein et al. submitted). The non-coding mitochondrial control region was chosen due to its high mutation rate and assumed selective neutrality. DNA extractions, primer usage, and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplifications and cloning of the first two markers were performed according to the protocols described in Bronstein et al.13. To amplify a longer stretch of the COI gene we designed a new forward primer (TripCOI6+: 5′ AACATGCAACTAAGACGATGA 3′), that was used with the reverse primer COI1a23 to produce a 1347 bp amplicon. PCR reactions using this primer combination were performed in 50 µl containing 2.0 μl DNA (10–15 ng), 5 μl 10X High Fidelity PCR Buffer, 2.0 μl of 50 mM MgCl2, 1.0 μl of 10 mM dNTPs, 0.2 μl of each 50 mM forward and reverse primers, and 0.2 μl Platinum® Taq High Fidelity polymerase. PCR conditions were 2 min at 94 °C, 5 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 68 °C for 90 s, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 50 °C for 30 s, 68 °C for 90 s. For amplification of the CR we designed a new set of primers, the forward primer CR15fwd (5′ TACACATCGCCCGTCACTCT 3′) and the reverse primer CR08rev (5′ TTAACGGCCAAGCGCCTTT 3′) that generated an amplicon of ca. 590 bp. PCR reactions were performed in 25 µl containing 1.0 μl DNA (10–15 ng), 2.5 μl 10X TopTaq PCR Buffer, 2.0 μl of 50 mM MgCl2, 1.0 μl Q-Solution, 0.5 μl of 10 mM dNTPs, 0.25 μl of each 10 mM forward and reverse primers, and 0.25 μl TopTaq DNA polymerase. PCR conditions were 3 min at 94 °C, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 60 s, followed by a final elongation step at 72 °C for 10 min.

All bindin sequences were cloned prior to sequencing (for details see ref. 13). Sequencing (in both directions) was performed at Microsynth Austria GmbH using PCR primers and the set of internal primers as listed in Bronstein et al.13. COI sequences are deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KY314757 to KY314770, CR sequences under accession numbers KY515240 to KY515264, and bindin sequences under accession numbers KY314771 to KY314783.

Sequence statistics and phylogenetic tree reconstruction

Phylogenetic analyses were based on the COI, CR and bindin datasets. In order to facilitate the integration of our sequences with previously published data, three COI datasets were created: the first containing 50 COI sequences, 1126 bp long, of our de-novo Kermadec sequences and the sequences published by Bronstein et al.13. The second (531 bp long) containing 13 T. kermadecensis n. sp., 23 T. g. elatensis and 34 T. g. gratilla sequences plus an additional 14 T. ventricosus and 6 T. depressus with Lytechinus variegatus serving as outgroup (see Tables S1 and S2 for details). The third COI dataset (448 bp long) comprised 13 sequences generated in the present study plus 326 Tripneustes COI sequences from the literature (Table S2). Our full length bindin alignment comprises 55 sequences and has a length of 1256 bp (after removal of gaps and ambiguously aligned sites) including parts of both exons and the intron. The CR alignment comprises 22 sequences and has a length of 446 bp. Alignable sequences from each marker (i.e., the mitochondrial COI and CR, and nuclear bindi n including both exons and the intron) were concatenated from a subset of specimens for which all three markers were sequenced from the same individual. The concatenated alignment comprises 19 sequences with a total length of 2828 bp.

Raw sequences were edited and aligned manually using BioEdit v.7.1.329 and AliView v.1.1830. Median-Joining networks were calculated for the 448 bp COI dataset with PopArt31 applying the default settings. For the other datasets positions with gaps were removed using TrimAl v.1.432 and identical sequences identified using DAMBE v.6.0.133. Phylogenetic reconstructions were performed using both the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method and Bayesian Inference (BI). ML analyses were all performed with RAxML v.7.2.634 while BI analyses were conducted with MrBayes v.3.2.235. Partitions and optimal substitution models were determined in PartitionFinder v.1.1.136 using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) metric for model selection37. The best-fitting substitution models for the 1126 bp COI datasets were GTR + G and HKY + G (on all codon positions) for ML and BI, respectively. For the 531 bp COI datasets best-fitting substitution models were GTR + G and HKY + I (on all codon positions) for ML and BI, respectively. The bindin gene was partitioned by 1st and 2nd exons, the intron, and codon positions. The best fitting model for the bindin dataset was GTR + G for the ML analyses and HKY + G for the BI analyses. The best-fitting substitution models for the 446 bp CR dataset were GTR + G and K80 + I, for the ML and BI analyses respectfully. For the concatenated analysis, the best-fitting model for the ML analysis was GTR + G (for all of the markers used). For the BI analysis, best models were HKY + G for CR, COI and the bindin intron, and HKY for the two bindin exons.

RAxML tree reconstructions were carried out using 100 random starting trees. Branch support was computed based on 1000 bootstrap replications. Analyses in MrBayes were calculated for each of the datasets applying the respective model parameters. The analyses were run for 10 million generations each (2 runs with 4 chains, one of which was heated), sampling every 100th tree. Convergence was assessed according to the average standard deviation of split frequencies <0.01. The runs were also visually checked by plotting generations vs. likelihood scores in Tracer v.1.638 to assess whether the two runs had converged and when the stationary phase was reached. In a conservative approach, the first 25% of trees were discarded as burn-in and a 50% majority rule consensus tree was calculated from the remaining 75,000 trees.

Uncorrected mean p-distances and Kimura two-parameter (K2P39) genetic distances within and between species/clades were calculated based on the bindin dataset using MEGA v.6.0.640.

Morphological analysis

To account for potential ontogenetic variation, Kermadec Tripneustes specimens ranging from 58.7 to 127.7 mm in diameter were examined and compared to the other Tripneustes species. External appearance and coloration patterns (epidermis, pedicellariae, spines, and tube-feet) were noted for each specimen. The skeletal components (corona, plates, tuberculation, etc.) of selected specimens were assessed following removal of the soft tissue. This was done using enzymatic digestion of the soft tissue with Enzyrim (Bauer Handels GmbH, Germany) following the manufacturers protocol. Measurements of both the corona (height and diameter) and peristome were performed using digital Vernier calipers to the nearest 0.1 mm. Pedicellariae and elements of the lantern were observed and measured under a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (JEOL, JSM-6610LV) at the Central Research Laboratories of the Natural History Museum in Vienna, Austria. Pedicellariae and lantern elements were coated with gold prior to SEM examinations and visualized using the secondary electron images, while tubefeet spicules were not sputter-coated and examined in low vacuum mode employing back scatter electron images.

Systematics

Tripneustes kermadecensisn. sp

ZooBank LSID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:19A5CD2E-6D57-4F03-BDF7-AA1A3E5D4B80 .

Holotype

Auckland War Memorial Museum, Auckland, New Zealand (AIM MA) specimen AIM MA73563 (isolate nr. Ker907), a cleaned corona, spines and lantern, collected by J. David Aguirre and Libby Liggins on 31/10/2015 at a depth of 0 to 10 m. A tissue sample (tubefeet) has been deposited together with the holotype.

Paratypes

Two cleaned coronas (AIM MA73564 and Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Geologisch-Paläontologische Abteilung, Vienna, Austria (NHMW-Geo) NHMW-Geo 2017/0016/0001 [formerly MA 121530.10]; isolate Ker903 and Ker910 respectively) and five intact, formalin-fixed specimens preserved in ethanol (AIM MA73565, AIM MA73566, and National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Wellington, New Zealand (NIWA) 116558 [=isolates Ker902, Ker904, and Ker911]; Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, 3. Zoologische Abteilung, Sammlung Evertebrata Varia, Vienna, Austria (NHMW-EV) NHMW-EV 20452 and 20453 [=isolates Ker901, and Ker906]); collection details as for holotype.

Type locality

West of Meyer Islands (S 29°14′39.06″ W177°52′46.56″), near Raoul Island, Kermadec Islands, New Zealand. Tripneustes were abundant in this habitat of rock spurs that had small areas of horizontal rock, to near vertical rock walls (0–10 m) leading to a base of sand (starting at 11 m and gently sloping deeper).

Additional material

Three intact, formalin-fixed specimens preserved in ethanol (AIM MA121530.05, AIM MA121530.08, and NIWA 116559 [isolates Ker905, Ker908, and Ker909, respectively]) and tissue (gonad) samples (Ker001, Ker123, Ker124, Ker218, Ker219, Ker243, Ker378) from various sites in the Kermadec Islands; for details on localities and voucher specimens see Supplementary Table S1.

Etymology

Named after the type region, the Kermadec Islands, a subtropical island arc in the South Pacific Ocean, ca. 800–1,000 km NE of New Zealand’s North Island.

Vernacular name

Locally species of Tripneustes are referred to as “Lamington urchin” based on the superficial similarity with coconut-covered chocolate cakes, termed “Lamington cake”.

Diagnosis

A species of Tripneustes with ambulacral primary tubercles occurring on every fourth plate ambitally; flattened test (height usually <60% test diameter (TD)); large peristomal opening (ca. 25%TD) without sunken margin; presence of one to two plates for every four ambulacral plates occluded from perradial suture (except in smallest specimens <80 mm TD); primary series of interambulacral tubercles continuous from peristome to apex; tubercles large; secondary interambulacral tuberculation reduced above ambitus.

Description of the holotype (AIM MA73563)

Corona large, 94.4 mm in horizontal diameter; circular in outline. In profile corona low, bun-shaped with 46.9 mm test height; ambitus low, at about one third of test height (Fig. 3).

Apical disc hemicyclic, with oculars I and V insert. All genital plates, as well as the insert oculars bear secondary tubercles along the periproctal margin, forming a distinct circle around the periproct. Remaining plate surface covered with scattered miliary spines and numerous granules (pedicellariae attachment sites). Gential pores circular and located in outer half of the plates, about their own diameter from the margin. Madreporic pores minute, forming a well-defined, slightly raised patch.

Periproct large (6.75 mm, ~7.2%TD), circular; densely covered with polygonal scales; anus almost central.

Ambulacra trigeminate, compounded in echinoid style; pores forming three distinct vertical series, the innermost of which are almost straight, while the other two are distinctly wiggling. Primary tubercles occurring on every other plate close to the peristome, every third plate in the outer half of the oral surface, and on every fourth plate ambitally (Figs 3 and 4C). Adapically primary tubercles typically occur on every third plate. Numerous ambulacral plates are occluded from the perradial suture, typically those located immediately below and/or above the plate bearing the ambulacral primary tubercles, forming a “pseudo-polyporous” arrangement (sensu Mortensen25). Plate occlusion and enlargement of plates in between leads to rather irregular zigzagging of the perradial suture (Fig. 4C). Aboral ambulacral pores belong to type P2 (sensu Smith41), with comparatively narrow attachment areas, whereas oral ones have distinctly wider attachment areas and approach type P3.

Interambulacra fully tuberculate on oral side with up to five subequal tubercles per plate in the subambital region. At the ambitus, the size of the enlarged secondary tubercles diminishes rapidly, with almost none occurring beyond six plates above the ambitus. The primary tubercle columns, in contrast, persist as large, prominent tubercles with areoles taking up most of the plate height. Primary and secondary tubercles with well-developed areoles; secondary tuberculation very dense, especially so in the ambulacra.

Peristome large (25.7 mm, ~27.2%TD), circular, with prominent buccal notches (without distinct tag) that extend to the third interambulacral tubercle; peristomal margin barely sunken (Fig. 3E). Buccal membrane densely plated close to the mouth opening; buccal plates form broken circle; plating outside of buccal plate circle is less dense, with gaps of up to a single plate width around each platelet, but becomes denser at peristomal margin again; platelets of the buccal membrane bear numerous pedicellariae, but no spines (Fig. 10).

Lantern of typical camarodont type with large foramen magnum and fused epiphyses; rotulae rectangular with poorly differentiated triangular part adaxially; compasses showing short bifurcations distally, which are comparatively flattened and wide (Fig. 11). Auricles connected at top, relatively wide.

Primary spines up to 15.5 mm in length; almost straight sided in proximal half and slightly tapering to a blunt point distally; bases very high (almost 1.7 times their width) and slightly constricted below milled ring; in cross-section spines consist of dozens of wedges forming concentric circles. Microsculpture of wedges in primary and secondary spines saw-tooth-like, minute (Fig. 2K–M), very similar to that of T. ventricosus.

Tridentate pedicellariae apparently absent; globiferous pedicellariae (Fig. 2A–E) abundant, with single, large and curved end-tooth and a long neck; basal part of globiferous pedicellariae with teardrop-shaped outline; stalk glands present; ophiocephalous pedicellariae (Fig. 2F–J) very abundant, with fully denticulate margin; triphyllous pedicellariae present, not specialized.

Spicules in tubefeet mainly of large, C-shaped type; dumb-bell shaped spicules present, but deeply embedded in skin and usually not apparent in BSE-SEM images.

Aboral coloration of naked corona light pink to light violet; darker along perradial and interradial sutures; outer margin of apical disc traced by a distinct reddish-pink line; oral side less colored, white along the perradial and interradial sutures, as well as the pore zones, only the area adjacent to the interambulacral primary tubercles more intensely colored.

Living animals black with dense cover of white spines (Fig. 3A); spine posture radial, not bent over ambulacra under normal conditions.

Additional description based on paratypes and other material

Corona large, reaching up to 130 mm in horizontal diameter, with test height ranging from 46.7 to 61.2%TD (mean = 51.2, SD = 4.2, n = 11). Apical disc usually hemicyclic, with oculars I and V insert. In the largest specimen (TD = 127.7 mm), however, oculars II and IV are also insert. In the smallest specimen studied (Fig. 10B; TD = 58.7 mm) all five genital pores are already open, but are located very close to the plate margin (about their own diameter from the margin in the larger ones). Periproct large, ranging from 7.2 to 8.7%TD (n = 3), circular and densely covered with polygonal scales; anus almost central (Fig. 10).

In the smallest specimen examined all plates reach the perradial suture, in moderate (>80 mm TD) to large sized specimens, in contrast, numerous ambulacral plates are occluded from the perradial suture, typically those located immediately below and/or above the plate bearing the ambulacral primary tubercles, forming a “pseudo-polyporous” arrangement.

Peristome (Fig. 10A) large, ranging from 23.2 to 27.7%TD (mean = 25.2, SD = 1.6, n = 11), circular, with prominent buccal notches (without distinct tag) that extend to the third interambulacral tubercle in larger specimens, but only the second to third one in the smallest specimen studied (here TD = 58.7 mm).

Compasses of lantern show short bifurcations distally at all examined growth stages, with incision of distal end only increasing slightly during growth (Fig. 11).

Primary spines of up to 9 mm length in the smallest and up to 16 mm length in the largest specimen examined. Color is usually white, but sometimes shows a pinkish tinge.

Spicule shape is slightly variable both within an individual and between individuals. At the base of the tubefeet mainly medium-sized, C-shaped spicules occur, typically with blunt or swollen ends (Fig. 12H). Their shape is somewhat intermediate between the larger C-shaped sclerites with pointed ends that occur mid-length of the tubefeet (Fig. 12E) and the dumb-bell shaped spicules (Fig. 12D). In most specimens, regardless of their fixation (alcohol or formaldehyde) the dumb-bell shaped ossicles are deeply embedded in skin and usually not readily observed in BSE-SEM images. They are most common in the distal third of the tubefeet, just below the terminal disc (Fig. 12A).

Tubefeet spicules of Tripneustes species. (A,D,E,H) Tripneustes kermadecensis n. sp. (Meyer Islands, New Zealand; paratype MA 121530.10); (B,F,I) Tripneustes gratilla gratilla (Philippines; CAS 187193); (C,G,J) Tripneustes gratilla elatensis (Aquaba, Jordan; NHMW NHMW-EV 20454). Top row: terminal disc; middle row: spicules from distal half of tube foot; Bottom row: spicules from base of tube foot. All images are backscatter electron images. 100 µm scale bar valid for images A to C; 50 µm scale bar for imaged (D) through (J).

Differential diagnoses

Tripneustes depressus from the Eastern Pacific differs from T. kermadecensis n. sp. by its more prominent interambulacral tuberculation with multiple enlarged secondary tubercles present even a few plates below the apex and presence of ambulacral primary tubercles on every second (adoral and adapical) to third (ambital) plate; only rarely are there three plates in between adjacent primary tubercles ambitally. Occluded plates are less common than in T. kermadecensis n. sp. Detailed morphological descriptions for T. depressus, however, have not been published so far and further material needs to be studied to gain a good understanding about its variability.

Tripneustes gratilla gratilla differs from T. kermadecensis n. sp. by its higher test (typically hemispherical in profile with TH > 63%TD); ambulacral primary tubercles on every second (oral) to third plate (aborally); regular zigzagging at perradial suture and absence of occluded plates (Fig. 4A); similar interambulacral tuberculation pattern, but tubercles much smaller (areoles of primary tubercles typically taking up only half of plate height); smaller peristome (23.3–30.8%TD, mean = 28.1, SD = 3.0, n = 10), with distinctly sunken margin; deeply bifurcate distal compass ends (see ref. 13: Fig. 6I–L); much more abundant dumb-bell shaped spicules in the tubefeet (Fig. 12B,F), occurring in uppermost epidermal layers.

Tripneustes gratilla elatensis has a similar test shape as T. kermadecensis n. sp., albeit slightly less depressed (mean TH 54%TD). It differs from the latter by its ambulacral primary tubercles on every second (oral) to fifth plate (aborally); regular zigzagging at perradial suture and absence of occluded plates; much sparser interambulacral tuberculation, with primary interambulacral tubercles typically only occurring on every second plate aborally; smaller areoles of primary tubercles, typically taking up only half of plate height; larger peristome (32.0–47.3%TD, mean = 36.9, SD = 4.1, n = 13), with deeper buccal notches, and narrower auricles.

Tripneustes ventricosus from the Caribbean and Atlantic Ocean differs from T. kermadecensis n. sp. by its higher test (typically hemispherical in profile with TH > 59%TD); ambulacral primary tubercles on every second (oral) to third plate (ambitus and aborally); regular zigzagging at perradial suture, except at ambitus, where every third plate is strongly widened perradially to accommodate a second column of enlarged tubercles (Fig. 4D); plates between these enlarged plates tapering perradially, with only one of them typically reaching the perradius (Fig. 4D); interambulacral tuberculation more prominent with multiple enlarged secondary tubercles present even a few plates below the apex; tubercles smaller (areoles of primary tubercles typically taking up only half of plate height); much smaller peristome (18.8–50.0%TD, mean = 30.0, SD = 7.3, n = 29), with distinctly sunken margin and narrower auricles; absence of dumb-bell shaped spicules in tubefeet (fidé Mortensen25: p. 495).

Discussion

Accurate assessment of species diversity is essential to nearly all areas of biology: studies of biodiversity, ecology, conservation, and policy-making all necessitate correct species identification. However, fundamental to the process of allocating individuals to a given species are the criteria by which species are defined and delimited, which are in turn determined by the concept of what constitutes a species. Classical taxonomists classified individuals as members of a species based on a suite of shared morphological characters that are diagnostic and differentiate them from other such morphologically defined groups. The biological species concept42, 43 defines species based on their ability to interbreed, while the phylogenetic species concept attempts to delimit species boundaries based on phylogenetic reconstructions, mostly using mitochondrial DNA haplotypes (e.g., refs 44,45,46). In fact, numerous other species concepts exist in the evolution literature (reviewed in ref. 47) and the debate over the validity of different concepts is unlikely to be resolved in the near future. Nevertheless, concordance in species allocation obtained using different species concepts or by using different data sets within a particular taxon, would significantly improve our level of certainty in correctly assigning any given group of individuals to species.

The current study investigated the taxonomic status of Tripneustes from the remote Kermadec Islands and examined its phylogenetic relationships with the other members of this genus. We employed two independent strategies for species delimitation, a morphological taxonomic approach, and a molecular phylogenetic strategy, to draw robust conclusions and to check for discrepancies between the two.

As species of Tripneustes have long served as models for marine speciation and biogeography, they have received considerable attention in the scientific literature6, 13, 22,23,24, 48, 49 Still, the high interspecific morphological similarity of Tripneustes complicates species delimitation in this genus6, 48. Nonetheless, some morphological differences between species of Tripneustes are pronounced and suggest that our knowledge about this genus is most likely incomplete. RS Tripneustes for example shows substantial morphological differences, in comparison to its IWP congenerics13. Likewise, the morphological data on Kermadec Tripneustes presented here shows significant variation separating this lineage from any of the other congeners (see above) indicating that Kermadec Tripneustes represents a novel species.

The DNA sequence data corroborate these results: Both mitochondrial markers (COI and CR) as well as the nuclear marker (bindin) unambiguously resolve T. kermadecensis n. sp. as a strongly supported monophyletic clade (Figs 5–8). This finding provides independent support for treatment of the Kermadec population as a new species of Tripneustes – Tripneustes kermadecensis n. sp. As with the COI dataset, our new mitochondrial marker (CR) reflects the strong divergence of T. kermadecensis n. sp. from its IWP congeners (Fig. 6, clade A). In fact, our analyses show that T. kermadecensis n. sp. is highly diverged (Table 2 and Figs 7–9) and, rooted with Lytechinus variegatus, is recovered as a sister clade to all other Tripneustes (Fig. 5). The divergence of T. kermadecensis n. sp. may thus have started very early, potentially predating the split of the Atlantic T. ventricosus from the other IWP species, as also indicated by its unique sequence features. These latter features, namely insertions, deletions or inversions, represent unique events in the evolutionary history of a lineage. Compared to all other Tripneustes species for which bindin sequences are available, only T. kermadecensis n. sp. lacks a section of ~169 bp at the 5′ end of its bindin intron. In contrast, at the exact same position, T. ventricosus and T. g. gratilla contain a transposon called DNA-1-2_SP and T. g. elatensis features a unique inverted repeat (see ref. 13 for details). Mapping of the unique sequence features (that were excluded from the alignments used for the phylogenetic analyses) onto the bindin tree, shows perfect match with the tree topology (Fig. 8, Supplementary Fig. S2), providing further independent support for the relationships among clades, the polyphyly of T. g. gratilla, and the distinctiveness of T. g. elatensis and T. kermadecensis n. sp. clades.

Interestingly, the COI sequence data generated in the current study contradicts the results of a previous study on Tripneustes from this region24. Liggins et al. found only a single COI haplotype in the Kermadec population, which was shared with other IWP populations of T. g. gratilla. Unfortunately, the specimens and tissues used by Liggins et al.24 are no longer available, precluding verification of their results. Based on our new analysis, however, which utilized a significantly larger portion of the COI gene than that of the original paper by Liggins et al., as well as a second independent mitochondrial marker, it is safe to conclude that none of the specimens collected for the present study share mitochondrial haplotypes with IWP Tripneustes. Our data from the mitochondrial control region, as well as from the nuclear bindin loci, reaffirm the novel COI results and provide strong independent support for the monophyly of T. kermadecensis n. sp. Additionally, in contrast to the mitochondria-nuclear discordance of the phylogenetic signal in Red Sea Tripneustes, apparently caused by mitochondrial introgression13, the signal from the different markers in T. kermadecensis n. sp. is highly congruent (Figs 5–8) and no introgression seems to have taken place.

Tripneustes kermadecensis offers a novel example of cryptic speciation in the sea and peripheral speciation in the Indo-Pacific. Several Indo-Pacific taxa indicate that speciation, by founder events and subsequent isolation of the population (peripatric speciation50), is a common mode of speciation with a distinct geographic signature51,52,53. Peripheral locations and particularly islands, such as the Hawaiian Archipelago, Lord Howe Island, and now the Kermadec Islands, should be expected to harbor endemic species whose sister taxa are widespread in the Indo-Pacific. The marine biodiversity of the Kermadec Islands is still actively being discovered and described (reviewed in refs 14 and 16) – undoubtedly further examples of cryptic speciation in such an isolated, peripheral Pacific Island are yet to be documented.

Conclusions

The evidence put forward in this study asserts the assignment of Kermadec Tripneustes to a new species. T. kermadecensis n. sp. can be straightforwardly differentiated morphologically as well as by molecular genetic diagnostics, and its unique sequence features. It forms a distinct, strongly supported, genetic clade using both mitochondrial and nuclear markers and appears to be the earliest diverging species of Tripneustes known to date.

Identifying cryptic speciation has far reaching implications on conservation efforts, particularly for highly localized endemic species. Fortunately, the described population of Tripneustes kermadecensis resides within the Kermadec Island Marine Reserve that was established in 1990 by New Zealand’s Department of Conservation. Furthermore, the current Marine Reserve is proposed to be extended from 12 nautical miles around each island to 200 nautical miles to form the future Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary (http://www.mfe.govt.nz/marine/kermadec-ocean-sanctuary; last accessed 02.05.2017). Covering 620,000 km2 the Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary would be one of the world’s largest protected areas harboring over 150 species of fish, 39 species of seabirds, 35 species of whales and dolphins, and numerous other marine species unique to this area. Identifying T. kermadecensis as a new species in this area highlights the gaps in our current knowledge about this remote and unique oceanic region. In an era of global change and increased anthropogenic pressure, protection of pristine ocean environments, such as the Kermadec Islands, is paramount in our attempts to maintain and protect marine biodiversity.

References

Palumbi, S. R. Molecular biogeography of the Pacific. Coral Reefs 16, S47–S52 (1997).

Palumbi, S. R., Grabowsky, G., Duda, T., Geyer, L. & Tachino, N. Speciation and population genetic structure in tropical Pacific sea urchins. Evolution 51, 1506–1517 (1997).

Palumbi, S. R. & Lessios, H. A. Evolutionary animation: How do molecular phylogenies compare to Mayr’s reconstruction of speciation patterns in the sea? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102, 6566–6572 (2005).

Bronstein, O. & Loya, Y. The Taxonomy and Phylogeny of Echinometra (Camarodonta: Echinometridae) from the Red Sea and Western Indian Ocean. PLoS ONE 8, e77374 (2013).

Lawrence, J. M. & Agatsuma, Y. Tripneustes. In Sea Urchins: Biology and Ecology (ed. Lawrence, J. M.) 491–507 (Elsevier, 2013).

Mortensen, T. H. A monograph of the Echinoidea Vol. 1 (Reitzel, C. A., 1928–51).

Valentine, J. P. & Edgar, G. J. Impacts of a population outbreak of the urchin Tripneustes gratilla amongst Lord Howe Island coral communities. Coral Reefs 29, 399–410 (2010).

Mos, B., Cowden, K. L. & Dworjanyn, S. A. Potential for the commercial culture of the tropical sea urchin Tripneustes gratilla in Australia. Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation RIRDC Publication No. 12/052 (2012).

Cyrus, M. D., Bolton, J. J., Scholtz, R. & Macey, B. M. The advantages of Ulva (Chlorophyta) as an additive in sea urchin formulated feeds: effects on palatability, consumption and digestibility. Aquaculture Nutrition 21, 578–591 (2015).

Manuel, J. I. J. et al. Growth Performance of the Sea Urchin, Tripneustes gratilla in Cages Under La Union Condition, Philippines. International Scientific Research Journal 1, 195–202 (2013).

Chen, Y. C., Chen, T. Y., Chiou, T. K. & Hwang, D. F. Seasonal variation on general composition, free amino acids and fatty acids in the gonad of taiwan’s sea urchin Tripneustes gratilla. Journal of Marine Science and Technology 21, 723–732 (2013).

Rahman, S., Tsuchiya, M. & Uehara, T. Effects of temperature on hatching rate, embryonic development and early larval survival of the edible sea urchin. Tripneustes gratilla. Biologia 64, 768–775 (2009).

Bronstein, O., Kroh, A. & Haring, E. Do genes lie? Mitochondrial capture masks the Red Sea collector urchin’s true identity (Echinodermata: Echinoidea: Tripneustes). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 104, 1–13 (2016).

Duffy, C. A. J. & Ahyong, S. T. Annotated checklist of the marine flora and fauna of the Kermadec Islands Marine Reserve and northern Kermadec Ridge, New Zealand. Bulletin of the Auckland Museum 20, 19–124 (2015).

Francis, M. P. & Duffy, C. A. J. New records, checklist and biogeography of Kermadec Islands’ coastal fishes. Bulletin of the Auckland Museum 20, 481–495 (2015).

Trnski, T. & de Lange, P. J. Introduction to the Kermadec Biodiscovery Expedition 2011. Bulletin of the Auckland Museum 20, 1–18 (2011).

Farquhar, H. A Contribution to the History of New Zealand Echinoderms. Journal of the Linnean Society of London, Zoology 26, 186–198 (1897).

McKnight, D. G. Some echinoderms from the Kermadec Islands. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 2, 505–526 (1968).

Schiel, D. R., Kingsford, M. J. & Choat, J. H. Depth distribution and abundance of benthic organisms and fishes at the subtropical Kermadec Islands. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 20, 521–535 (1986).

Cole, R. G., Creesel, R. G., Grace, R. V., Irving, P. & Jackson, B. R. Abundance patterns of subtidal benthic invertebrates and fishes at the Kermadec Islands. Marine Ecology Progress Series 82, 207–218 (1992).

Gardner, J. P. A., Curwen, M. J., Long, J., Williamson, R. J. & Wood, A. R. Benthic community structure and water column characteristics at two sites in the Kermadec Islands Marine Reserve, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 40, 179–194 (2006).

Lessios, H. A., Kane, J. & Robertson, D. R. Phylogeography of the pantropical sea urchin Tripneustes: contrasting patterns of population structure between oceans. Evolution 57, 2026–2036 (2003).

Zigler, K. S. & Lessios, H. A. Evolution of bindin in the pantropical sea urchin Tripneustes: comparisons to bindin of other genera. Molecular Biology and Evolution 20, 220–31 (2003).

Liggins, L., Gleeson, L. & Riginos, C. Evaluating edge-of-range genetic patterns for tropical echinoderms, Acanthaster planci and Tripneustes gratilla, of the Kermadec Islands, southwest Pacific. Bulletin of Marine Science 90, 379–397 (2014).

Mortensen, T. A monograph of the Echinoidea.Vol III. Camarodonta (Reitzel, C. A., 1943).

Coppard, S. E., Kroh, A. & Smith, A. B. The evolution of pedicellariae in echinoids: an arms race against pests and parasites. Acta Zoologica 93, 125–148 (2012).

Verrill, A. E. Notes on the Radiata in the Museum of Yale College, with Descriptions of new Genera and Species. No. 5. - Notice of a Collection of Echinoderms from La Paz, Lower California, with Descriptions of a new Genus. Transactions of the Connecticut Acadademy of Arts and Sciences 1, 371–376 (1868).

Bao, W. & Jurka, J. DNA transposons from Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Repbase Reports 8, 2109–2109 (2008).

Hall, T. A. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series 41, 95–98 (1999).

Larsson, A. AliView: a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics 30, 3276–3278 (2014).

Leigh, J. W. & Bryant, D. popart: full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 6, 1110–1116 (2015).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Xia, X. DAMBE5: A comprehensive software package for data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30, 1720–1728 (2013).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690 (2006).

Ronquist, F. & Huelsenbeck, J. P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574 (2003).

Lanfear, R., Calcott, B., Ho, S. Y. W. & Guindon, S. PartitionFinder: Combined Selection of Partitioning Schemes and Substitution Models for Phylogenetic Analyses. Molecular Biology and Evolution 29, 1695–1701 (2012).

Schwarz, S. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. The Annals of Statistics 6, 461–464 (1978).

Rambaut, A., Drummond, A. J. & Suchard, M. Tracer v1.6 (2013).

Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. Journal of Molecular Evolution 16, 111–120 (1980).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A. & Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30, 2725–2729 (2013).

Smith, A. B. A functional classification of the coronal pores of regular echinoids. Palaeontology 21, 759–789 (1978).

Dobzhansky, T. G. Genetics and the Origin of Species (Columbia University Press, 1937).

Mayr, E. Systematics and the origin of species, from the viewpoint of a zoologist (Harvard University Press, 1942).

Doan, T. M. & Castone, T. A. Using morphological and molecular evidence to infer species boundaries within Proctoporus bolivianus Werner (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae). Herpetologica 59, 432–449 (2003).

Hendrixson, B. E. & Bond, J. E. Testing species boundaries in the Antrodiaetus unicolor complex (Araneae: Mygalomorphae: Antrodiaetidae): “Paraphyly” and cryptic diversity. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 36, 405–416 (2005).

Flot, J. F. et al. Mitochondrial sequences of Seriatopora corals show little agreement with morphology and reveal the duplication of a tRNA gene near the control region. Coral Reefs 27, 789–794 (2008).

Zachos, F. E. Species Concepts in Biology. Historical Development, Theoretical Foundations and Practical Relevance (Springer, 2016).

Clark, H. L. Hawaiian & other Pacific Echini. Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 34, 205 (1912).

Dafni, J. A new subspecies of Tripneustes gratilla from the northern Red Sea (Echinodermata: Echinoidea: Toxopneustidae). Israel Journal of Zoology 32, 1–12 (1983).

Coyne, J. A. & Orr, A. H. Speciation (Sinauer Associates 2004).

Paulay, G. & Meyer, C. Diversification in the Tropical Pacific: Comparisons Between Marine and Terrestrial Systems and the Importance of Founder Speciation. Integrative and Comparative Biology 42, 922–934 (2002).

Bowen, B. W., Rocha, L. A., Toonen, R. J. & Karl, S. A. The origins of tropical marine biodiversity. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 28, 359–366 (2013).

Hodge, J. R. & Bellwood, D. R. The geography of speciation in coral reef fishes: the relative importance of biogeographical barriers in separating sister-species. Journal of Biogeography 43, 1324–1335 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge funding by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) grant P29508-B25 (“Phylogeny and evolution of edible sea urchins”). Expeditions to the Kermadec Islands were made possible by the RV Braveheart crew and the Commanding Officer and Ship’s Company of HMNZS Canterbury, with support from the Auckland Museum Institute, Auckland War Memorial Museum, the Pew Charitable Trusts, the Sir Peter Blake Trust, and the Institute of Natural and Mathematical Sciences, Massey University. We are grateful for the support of Māori iwi Ngāti Kuri and Te Aupōuri, the collecting help of Tom Trnski, J. David Aguirre, Phil Ross and Sam McCormack, and sample curation of Severine Hannam. We gratefully acknowledge Yossi Loya (Tel Aviv University) for facilitating access for the Red Sea material, Rich Mooi (California Academy of Sciences) for access to Philippine material, and Dan Topa (NHMW), for access to the Scanning Electron Microscope of the NHMW Central Research Laboratories. We further thank the Department of Agriculture of the Philippines, particularly the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) and the National Fisheries Research and Development Institute (NFDRI) for support of the 2014–2016 Verde Island Passage Expeditions of the California Academy of Sciences. Tissue samples used herein were collected by Rich Mooi under funding from NSF grant 12–57630 “Collaborative Proposal: Documenting Diversity in the Apex of the Coral Triangle: Inventory of Philippine Marine Biodiversity”. This research was financially supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): project P 29508-B25. Institutional support was provided by the Central Research Laboratories and the Department of Geology and Palaeontology at the Natural History Museum Vienna, Austria. Sample collection at the Kermadec Islands was supported by the Auckland Museum Institute, Auckland War Memorial Museum, the Pew Charitable Trusts, the Sir Peter Blake Trust, Institute of Natural and Mathematical Sciences, Massey University. Libby Liggins was supported by a Rutherford Foundation New Zealand Postdoctoral Fellowship. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.B. and A.K. conceived the idea of the research. L.L. collected specimens. O.B., A.K. and B.T. conducted the experiments. O.B. and A.K. analysed the results. O.B., A.K., L.L. and E.H. wrote the text and prepared the figures.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bronstein, O., Kroh, A., Tautscher, B. et al. Cryptic speciation in pan-tropical sea urchins: a case study of an edge-of-range population of Tripneustes from the Kermadec Islands. Sci Rep 7, 5948 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06183-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06183-2

This article is cited by

-

Changes in podial skeletons during growth in the echinoid Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus

Zoomorphology (2023)

-

Morphological and genetic divergence supports peripheral endemism and a recent evolutionary history of Chrysiptera demoiselles in the subtropical South Pacific

Coral Reefs (2022)

-

The population genetic structure of the urchin Centrostephanus rodgersii in New Zealand with links to Australia

Marine Biology (2021)

-

Implications of range overlap in the commercially important pan-tropical sea urchin genus Tripneustes (Echinoidea: Toxopneustidae)

Marine Biology (2019)

-

Mind the gap! The mitochondrial control region and its power as a phylogenetic marker in echinoids

BMC Evolutionary Biology (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.