Abstract

To evaluate the relationship between wall shear stress (WSS) magnitude and cerebral aneurysm rupture and provide new insight into the disparate computational fluid dynamics (CFD) findings concerning the role of WSS in intracranial aneurysm (IA) rupture. A systematic electronic database (PubMed, Medline, Springer, and EBSCO) search was conducted for all accessible published articles up to July 1, 2016, with no restriction on the publication year. Abstracts, full-text manuscripts, and the reference lists of retrieved articles were analyzed. Random effects meta-analysis was used to pool the complication rates across studies. Twenty-two studies containing CFD data on 1257 patients with aneurysms were included in the analysis. A significantly higher rate of low WSS (0–1.5 Pa) was found in ruptured aneurysms (odds ratio [OR] 2.17; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.73–2.62). The pooled analyses across 14 studies with low WSS showed significantly lower mean WSS (0.64 vs. 1.4 Pa) (p = 0.037) in the ruptured group. This meta-analysis provides evidence that decreased local WSS may be an important predictive parameter of IA rupture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With recent improvements and more diffuse use of cerebrovascular imaging methods, the detection of unruptured cerebral aneurysms has increased, and the incidence is thought to be as high as 7%1,2.

Whether to intervene or conservatively follow an incidentally found unruptured aneurysm (UA) remains a decisional challenge for clinicians and involves assessment of the rupture risk for each individual aneurysm in comparison with the morbidity risk carried by current treatments.

Accordingly, a good estimation of the probability of rupture of an intracranial aneurysm (IA) is of high value. Hemodynamics plays a central role throughout IA natural history, and shear stress has emerged as an important determinant of arterial physiological characteristics3.

Over four decades, much interest has been centered on the parameter of wall shear stress (WSS) from computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis. However, these extensive studies reported divergent and controversial findings on the correlation of low and high WSS with rupture4.

To facilitate a more accurate predictive assessment for IA rupture risk by CFD, we explored the relationship between WSS magnitude and cerebral aneurysm rupture using data obtained from the current literature, and provide new insight into the disparate CFD findings on the role of WSS in IA rupture.

Methods

The medical literature on hemodynamic analysis for IAs was reviewed up to July 1, 2016. Title, abstract, key words, and free text were searched using combinations of the following terms: “intracranial” or “cerebral,” “aneurysm” and “hemodynamics” or “computational fluid dynamic” and “wall shear stress” in PubMed, Medline, Springer, and EBSCO.

In addition, references from the publications obtained were checked for additional studies. Two investigators (G.Z. and M.S.) performed the systematic literature search.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) presence of data on WSS by CFD simulation, 2) English language study, and 3) at least five patients per study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) study not published in full, and 2) editorials, letters, review articles, guidelines, case reports, in vitro or cadaveric studies, and studies on animal experimentation.

Data Extraction

Two authors (G.Z. and M.S.) extracted the data independently, including study characteristics (name of the first author, year of publication, parameters, and aneurysmal characteristic including aneurysm status and morphology). The unit for WSS was converted and unified into Pascal (Pa) in our analysis.

Based on previous studies, we set two WSS threshold ranges in our analysis of 0–1.5 and 0–2.0 Pa as WSS ranges to cause pathological changes and to define pathological low WSS. This threshold value is considered responsible for endothelial cell dysfunction causing arterial wall remodeling5.

We studied the effect of aneurysm size on WSS value, stratifying aneurysms as small (<10 mm) and large (≥10 mm). Results were graphically represented by using scatter plots with regression. To further investigate hemodynamic risk factors contribute to aneurysm rupture, aneurysms were classified according to asymptomatic/symptomatic and regular/irregular (blebs, aneurysm wall protrusions, or multiple lobes were present). We performed an analysis for publications that adopted patient-specific inflow boundary conditions as patient-specific measurements may be necessary for accurate and reliable calculation of WSS.

Quality Assessment and Statistical Analysis

Two authors (G.Z. and M.S.) separately graded the quality of the studies using the STROBE (Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology) checklist (22 items). Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Meta-analysis was performed using the STATA 13 statistical package (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). We pooled data for random effects meta-analysis and calculated weighted mean differences and the 95% confidence intervals (CI). Dichotomous variables are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CI. Results are presented as the mean ± SD. Matched analysis was performed as appropriate. Significance was set at p < 0.05. Heterogeneity across studies was evaluated using the I2 statistic. We assessed publication bias using funnel plots and by applying the Egger test.

Results

PubMed, Medline, Springer, and EBSCO database searches using the abovementioned key words yielded 393, 240, 466, and 131 results, respectively. The results were limited to journal articles; duplicates were removed.

After abstract screening, a total 175 full-text manuscripts were retrieved, of which 22 met the inclusion criteria6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. In total, 1257 aneurysms from these 22 studies that performed CFD in search of correlations between aneurysmal hemodynamics and rupture were included in the analysis (Table 1).

Our analysis showed a significantly higher rate of low WSS for ruptured aneurysms (OR 2.17; 95% CI, 1.73–2.62) (Fig. 1). Subgroup analysis found that patients with internal carotid artery aneurysms, especially posterior communicating artery (PcomA) aneurysms, had higher low WSS occurrence in ruptured cases (Fig. 2). Similarly, significantly higher rates of WSS between 0–2.0 Pa was found in ruptured aneurysms (OR 2.12; 95% CI, 0.89–5.06). Eighteen of the 22 studies demonstrated a positive correlation between low WSS and IA rupture (Fig. 3). The pooled analyses across 14 studies with low WSS (0–1.5 Pa) showed significantly lower mean WSS (0.64 vs. 1.4 Pa) (p = 0.037) in the ruptured group. PcomA aneurysms also had lower average WSS (0.51 Pa), which was lower than that of middle cerebral artery (MCA) aneurysms (1.1 Pa). We compared the WSS values based on generalized versus patient-specific profiles, the former showed significantly higher mean WSS in ruptured aneurysms (2.9 ± 3.0 Pa versus 0.67 ± 0.4 Pa, p = 0.02). For unruptured aneurysms, it was 3.68 ± 3.8 Pa versus 1.59 ± 1.7 Pa (p = 0.054).

Positive correlation with high oscillatory shear index (OSI) and IA rupture was found in six of 15 reports (Fig. 4). The 15 studies, involving 453 ruptured and 686 unruptured cases, were analyzed to determine the association of OSI with ruptured IA, and the pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) between the ruptured and unruptured groups showed high OSI in the ruptured group, with no significance. There was significant asymmetry in the funnel plot for articles reporting mean WSS (normalized and not normalized), and the Egger test revealed the presence of publication bias (Fig. 5). Our meta-analysis suggests that mean WSS from large ruptured aneurysm was 1.1 ± 1.1 Pa, which was insignificantly lower than patients with small ruptured aneurysms (2.1 ± 2.8 Pa) (p = 0.42). Mean WSS was 0.48 Pa for large unruptured aneurysms and 2.6 ± 3.2 Pa for their small counterparts (p = 0.53). Yet, there was a possible trend towards statistical significance (R2 = 0.018, p = 0.094) regarding the correlation between aneurysm and diameter in ruptured cases (Fig. 6). Our findings found irregular shape aneurysms have been shown to be characterized by lower WSS (0.86 ± 0.61 versus 1.16 ± 0.67, p = 0.33). We also demonstrated a lower WSS in the symptomatic group than in asymptomatic group (0.51 ± 0.06 versus 0.75 ± 0.08, p = 0.078). At peak systole, increase in pressure were observed in the ruptured aneurysms than unruptured ones (497 ± 164.2 Pa in ruptured aneurysms vs. 382.4 ± 113.7 Pa in unruptured aneurysms).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study provides the first comprehensive meta-analysis of WSS in ruptured IA. Our study shows for the first time statistical WSS maps of ruptured and unruptured IA based on the current literature. Even though there appears to be general consensus on aneurysm initiation, aneurysm rupture risk poses more vexing questions28. Our findings suggest that low WSS may be an important contributing factor to cerebral aneurysm rupture.

WSS differed between location in the aneurysm and the parent artery. PcomA aneurysms had lower average WSS (0.51 Pa), which was lower than that of MCA aneurysms (1.1 Pa). Multiple comparisons showed that basilar artery aneurysms had the lowest average WSS, being lower than that of anterior communicating artery (AcomA) aneurysms. WSS in AcomA aneurysms was lower than that in MCA aneurysms29.

Aneurysm wall degeneration increases from the neck to the dome, and pathological studies have revealed that ruptures commonly occur at the top of the IA. It has also been found that WSS is lowest at the apex of the IA rather than its neck30. Narrow-necked aneurysms are more likely to produce a recirculating and sluggish flow near the fundus with associated low and oscillating WSS vectors, which can drastically affect shear rates and accelerate wall degeneration6,31. This critically low-flow condition depends on aspect ratios and dome diameter, especially when the aspect ratio is >1.632,33. In symmetric bifurcation, an inline inflow angle of 180° would also result in an area of stasis in the dome, leading to low WSS34.

Reduced velocities and flow recirculation are responsible for thrombus formation and further expansion of the aneurysm dome35,36. Ruptured aneurysms also have greater aneurysm areas under low WSS than unruptured aneurysms7.

It has recently been demonstrated that high WSS initiates aneurysm formation, whereas low WSS leads to spatial disorganization of endothelial cells and activation of the atherogenic and proinflammatory signal pathways37. The walls of ruptured aneurysms are fragile, possibly because of macrophage infiltration and the consequent apoptosis of smooth muscle cells and degradation of matrix proteins38. Nitric oxide (NO) is a key mediator of the effects of low and oscillatory WSS39. Moreover, selectin-mediated leukocyte rolling occurs at WSS near 0.4 Pa, and CFD analysis has repeatedly found that the WSS at aneurysm tips is below this value. Meanwhile, low WSS–induced expression of adhesion molecules, including vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1, reduced the rolling speed of inflammatory cells over the endothelium. The inflammatory cell–mediated degradation becomes even more pronounced upon the formation of intra-aneurysmal thrombosis, and favors aneurysmal rupture40. Atherosclerotic lesions also predominantly localize at sites that experience low shear, which can degrade the integrity of the aneurysm wall41.

Other studies have consistently reported that low WSS in the aneurysm region might help predict rupture6,7,42. Takao et al. found that the minimum WSS in the ruptured aneurysms group was half (absolute value 0.2 dynes/cm2) of that of the unruptured group43. Moreover, the flow characteristics just prior to rupture have been reported44,45, where both studies demonstrated low WSS on the aneurysm sacs before their rupture. Although the literature on this is scarce, some studies support the notion that WSS decreases sharply in the bleb region after blister formation8,46.

Some authors have reported that high OSI correlates with the etiology and location of atherosclerotic plaques, endothelial damage, aneurysm formation, and rupture. High OSI modulates the gene expression of endothelial cells to upregulate endothelial surface adhesion molecules, cause dysfunction of flow-induced NO, increase endothelial permeability, and thereby promote the rupture process7,8,47. In our analysis, six of fifteen reports found a positive correlation between high OSI and IA rupture. However, the pooled SMD between ruptured and unruptured groups showed high OSI in the ruptured group, but without significance. Nonetheless, some CFD studies have also suggested a role for high WSS in aneurysm rupture48. Therefore, discerning the actual cause predisposing these lesions to rupture is challenging, but it is likely the multiplicative effect of a handful of factors.

The role of WSS in rupture has not been conclusively elucidated. Endothelial cell responses to low WSS have been investigated in various in vitro studies, and excessively low focal hemodynamic WSS may be one of the main factors leads to decreasing resistibility and structural fragility of the aneurysmal wall9. A low shear magnitude can promote macrophage-related chronic inflammation and atherosclerotic changes. These atherosclerotic inflammatory changes and metalloproteinase production by macrophages can predispose wall to thinning and further rupture. As previous study found, atherosclerotic changes were seen more frequently in the wall of ruptured aneurysms28. Meanwhile, the activation of transcription factor NF-κB is prolonged under low WSS conditions. In addition, endothelial cells also upregulate the expression of genes involved in various processes such as cell growth and inflammation under low WSS10.

As for the specification of inlet flow conditions, different authors adopted different assumptions across different studies. Generally, it is very difficult to obtain the patient-specific boundary conditions in clinical applications. Those reports did not use patient-specific measurements when creating CFD models may have affected their results. Previous report also showed that the use of idealized assumptions would have larger and instable WSS results11. Normalization by parent vessel WSS generated from the same CFD simulation minimizes the dependence on inlet conditions, especially when patient-specific inlet flow conditions are unavailable. The findings of this study emphasize that the choice of generalized or patient-specific inflow boundary conditions results in variations in WSS magnitude.

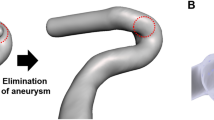

Parent vessel reconstruction with flow diverter is becoming the preferred endovascular modality for giant and complex IAs as it is an effective supplementary to coil embolism for types of complicated aneurysms. Flow diverter attempts to redirect blood flow and reduces inflow and outflow of an aneurysm leading to aneurysm thrombosis and obliteration. Platelets also activate as they pass over the device and they strut into the aneurysm with a long residence time, thereby promoting thrombus formation. Flow diverters are expected to provide a scaffold which would promote the development of endothelial and neointimal tissue across the aneurysm neck while preserving patency of perforators and side branches. Unfortunately, delayed aneurysm rupture after flow diverter implantation has been reported without an understood mechanism which has tempered the enthusiasm for their widespread use. Xiang et al.12 suggest that flow diverter can generate stagnant aneurysmal flow and excessively low WSS, which may promote wall degradation via the inflammatory pathway. However, another study13 demonstrated that low post-implantation flow velocity, inflow rate, and shear rate are associated with fast occlusion times. Perhaps This reflects the race between formation of complete and stable thrombus and WSS-mediated inflammatory degradation of the aneurysmal wall. Meanwhile, the complication rate for unruptured aneurysms was significantly lower than that for ruptured IAs. Thus, the use of flow diverters in ruptured aneurysms poses a major clinical challenge. Larger case series are needed to define the safety role and indication of flow diverter application in such kind of clinical situations.

Limitations

There were limitations to this study. First, publication bias are limitations that affect all meta-analyses. Indicating by I2 values, the substantial heterogeneity existed. Second, disparity of acquisition technique and inflow boundary conditions might also be responsible for discrepant WSS results in enrolled studies. Caution should be used in drawing conclusions from these comparisons.

Conclusions

Decrease in local WSS may be an important predictive parameter responsible for IA rupture. The inconsistent findings of WSS value may be rationalized by small datasets, inconsistent parameter definitions, mechanistic complexity of IA rupture, and the compromises adopted in CFD simulations. Facilitating more accurate predictive models for IA rupture risk assessment from CFD in future studies will likely require better classification of aneurysms based on aneurysm location, morphology, perienvironment, and patient population, and the incorporation of cell biology, matrix biology, and aneurysmal wall imaging.

Change history

22 March 2018

A correction to this article has been published and is linked from the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has been fixed in the paper.

References

Li, M. H. et al. Prevalence of unruptured cerebral aneurysms in Chinese adults aged 35 to 75 years: a cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med 59, 514–521 (2013).

Vernooij, M. W. et al. Incidental findings on brain MRI in the general population. N Engl J Med. 357, 1821–1828 (2007).

Xiang, J. et al. CFD: computational fluid dynamics or confounding factor dissemination? The role of hemodynamics in intracranial aneurysm rupture risk assessment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 35, 1849–1857 (2014).

Cebral, J. R. et al. Association of hemodynamic characteristics and cerebral aneurysm rupture. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 32, 264–270 (2011).

Malek, A. M., Alper, S. L. & Izumo, S. Hemodynamic shear stress and its role in atherosclerosis. JAMA. 282, 2035–2042 (1999).

Xiang, J. et al. Hemodynamic-morphologic discriminants for intracranial aneurysm rupture. Stroke. 42, 144–152 (2011).

Jou, L. D., Lee, D. H., Morsi, H. & Mawad, M. E. Wall shear stress on ruptured and unruptured intracranial aneurysms at the internal carotid artery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 29, 1761–1767 (2008).

Russell, J. H. et al. Computational fluid dynamic analysis of intracranial aneurysmal bleb formation. Neurosurgery. 73, 1061–1068 (2013).

Kadirvel, R. et al. The influence of hemodynamic forces on biomarkers in the walls of elastase-induced aneurysms in rabbits. Neuroradiology. 49, 1041–1053 (2007).

Frosen, J. et al. Remodeling of saccular cerebral artery an- eurysm wall is associated With rupture: histological analysis of 24 unruptured and 42 ruptured cases. Stroke. 35, 2287–2293 (2004).

Venugopal, P. et al. Sensitivity of patient-specific numerical simulation of cerebral aneurysm hemodynamics to inflow boundary conditions. J Neurosurg. 106, 1051–1060 (2007).

Xiang, J. et al. Increasing flow diversion for cerebral aneurysm treatment using a single flow diverter. Neurosurgery. 75, 286–294 (2014).

Mut, F. et al. Association between hemodynamic conditions and occlusion times after flow diversion in cerebral aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg 7, 286–290 (2015).

Cebral, J. R. et al. Analysis of hemodynamics and wall mechanics at sites of cerebral aneurysm rupture. J Neurointerv Surg 7, 530–536 (2015).

Duan, G. et al. Morphological and hemodynamic analysis of posterior communicating artery aneurysms prone to rupture: a matched case-control study. J Neurointerv Surg 8, 47–51 (2016).

Fan, J. et al. Morphological-hemodynamic characteristics of intracranial bifurcation mirror aneurysms. World Neurosurg 84, 114–120 (2015).

Fukazawa, K. et al. Using computational fluid dynamics analysis to characterize local hemodynamic features of middle cerebral artery aneurysm rupture points. World Neurosurg 83, 80–86 (2015).

Goubergrits, L. et al. Statistical wall shear stress maps of ruptured and unruptured middle cerebral artery aneurysms. J R Soc Interface 9, 677–688 (2012).

Jing, L. et al. Morphologic and hemodynamic analysis in the patients with multiple intracranial aneurysms: ruptured versus unruptured. PLoS One. 10, e0132494 (2015).

Kawaguchi, T. et al. Distinctive flow pattern of wall shear stress and oscillatory shear index: similarity and dissimilarity in ruptured and unruptured cerebral aneurysm blebs. J Neurosurg. 117, 774–780 (2012).

Liu, J. et al. Morphologic and hemodynamic analysis of paraclinoid aneurysms: ruptured versus unruptured. J Neurointerv Surg 6, 658–663 (2014).

Liu, J., Fan, J., Xiang, J., Zhang, Y. & Yang, X. Hemodynamic characteristics of large unruptured internal carotid artery aneurysms prior to rupture: a case control study. J Neurointerv Surg 8, 367–372 (2016).

Lu, G. et al. Influence of hemodynamic factors on rupture of intracranial aneurysms: patient-specific 3D mirror aneurysms model computational fluid dynamics simulation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 32, 1255–1261 (2011).

Lv, N. et al. Hemodynamic and morphological characteristics of unruptured posterior communicating artery aneurysms with oculomotor nerve palsy. J Neurosurg. 125, 264–268 (2016).

Miura, Y. et al. Low wall shear stress is independently associated with the rupture status of middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Stroke. 44, 519–521 (2013).

Omodaka, S. et al. Local hemodynamics at the rupture point of cerebral aneurysms determined by computational fluid dynamics analysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 34, 121–129 (2012).

Schneiders, J. J. et al. Additional value of intra-aneurysmal hemodynamics in discriminating ruptured versus unruptured intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 36, 1920–1926 (2015).

Nixon, A. M., Gunel, M. & Sumpio, B. E. The critical role of hemodynamics in the development of cerebral vascular disease. J Neurosurg. 112, 1240–1253 (2010).

Chien, A. et al. Quantitative hemodynamic analysis of brain aneurysms at different locations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 30, 1507–1512 (2009).

Cebral, J. R., Sheridan, M. & Putman, C. M. Hemodynamics and bleb formation in intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 31, 304–310 (2010).

Valen-Sendstad, K., Mardal, K. A., Mortensen, M., Reif, B. A. & Langtangen, H. P. Direct numerical simulation of transitional flow in a patient-specific intracranial aneurysm. J Biomech. 44, 2826–2832 (2011).

Ujiie, H., Tamano, Y., Sasaki, K. & Hori, T. Is the aspect ratio a reliable index for predicting the rupture of a saccular aneurysm? Neurosurgery. 48, 495–503 (2001).

Yamaguchi, R., Ujiie, H., Haida, S., Nakazawa, N. & Hori, T. Velocity profile and wall shear stress of saccular aneurysms at the anterior communicating artery. Heart Vessels. 23, 60–66 (2008).

Baharoglu, M. I., Schirmer, C. M., Hoit, D. A., Gao, B. L. & Malek, A. M. Aneurysm inflow-angle as a discriminant for rupture in sidewall cerebral aneurysms morphometric and computational fluid dynamic analysis. Stroke. 41, 1423–1430 (2010).

Rayz, V. L. et al. Flow residence time and regions of intraluminal thrombus deposition in intracranial aneurysms. Ann Biomed Eng 38, 3058–3069 (2010).

Meng, H. et al. Complex hemodynamics at the apex of an arterial bifurcation induces vascular remodeling resembling cerebral aneurysm initiation. Stroke. 38, 1924–1931 (2007).

Dolan, J. M., Meng, H., Sim, F. J. & Kolega, J. Differential gene expression by endothelial cells under positive and negative streamwise gradients of high wall shear stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 305, C854–866 (2013).

Kataoka, K. et al. Structural fragility and inflammatory response of ruptured cerebral aneurysms. A comparative study between ruptured and unruptured cerebral aneurysms. Stroke. 30, 1396–1401 (1999).

Cheng, C. et al. Shear stress affects the intracellular distribution of eNOS: direct demonstration by a novel in vivo technique. Blood. 106, 3691–3698 (2005).

Ross, R. Atherosclerosis–an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 340, 115–126 (1999).

Kosierkiewicz, T. A., Factor, S. M. & Dickson, D. W. Immunocytochemical studies of atherosclerotic lesions of cerebral aneurysms. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 53, 399–406 (1994).

Yan, L., Zhu, Y. Q., Li, M. H., Tan, H. Q. & Cheng, Y. S. Geometric, hemodynamic, and pathological study of a distal internal carotid artery aneurysm model in dogs. Stroke. 44, 2926–2929 (2013).

Takao, H. et al. Hemodynamic differences between unruptured and ruptured intracranial aneurysms during observation. Stroke. 43, 1436–1439 (2012).

Mannino, R. G. et al. Do-it-yourself in vitro vasculature that recapitulates in vivo geometries for investigating endothelial-blood cell interactions. Sci Rep. 5, 12401 (2015).

Varela, A. et al. Elevated expression of mechanosensory polycystins in human carotid atherosclerotic plaques: association with p53 activation and disease severity. Sci Rep. 5, 13461 (2015).

Meng, H., Tutino, V. M., Xiang, J. & Siddiqui, A. High WSS or low WSS? Complex interactions of hemodynamics with intracranial aneurysm initiation, growth, and rupture: toward a unifying hypothesis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 35, 1254–1262 (2014).

Boussel, L. et al. Aneurysm growth occurs at region of low wall shear stress: patient-specific correlation of hemodynamics and growth in a longitudinal study. Stroke. 39, 2997–3002 (2008).

Cecchi, E. et al. Role of hemodynamic shear stress in cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 214, 249–256 (2011).

Shojima, M. et al. Magnitude and role of wall shear stress on cerebral aneurysm: computational fluid dynamic study of 20 middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Stroke. 35, 2500–2505 (2004).

Xu, J. et al. Morphological and hemodynamic analysis of mirror posterior communicating artery aneurysms. PLoS One. 8, e55413 (2013).

Yu, Y. et al. Analysis of morphologic and hemodynamic parameters for unruptured posterior communicating artery aneurysms with oculomotor nerve palsy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 34, 2187–2191 (2013).

Zhang, Y. et al. Influence of morphology and hemodynamic factors on rupture of multiple intracranial aneurysms: matched-pairs of ruptured-unruptured aneurysms located unilaterally on the anterior circulation. BMC Neurol. 14, 253 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. Clinical, morphological, and hemodynamic independent characteristic factors for rupture of posterior communicating artery aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg 8, 808–812 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos 81471760, 81671655).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L., Y.Y. designed the study; G.Z. and M.S. developed the methodology and performed the analyses; G.Z. and M.S. collected the data; G.Z., M.S. and Y.Z. analyzed the data; and G.Z. wrote the first draft. All the authors contributed to the review and revision of the manuscript, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, G., Zhu, Y., Yin, Y. et al. Association of wall shear stress with intracranial aneurysm rupture: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 7, 5331 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05886-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05886-w

This article is cited by

-

Image-based hemodynamic simulations for intracranial aneurysms: the impact of complex vasculature

International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery (2024)

-

Increased aneurysm wall permeability colocalized with low wall shear stress in unruptured saccular intracranial aneurysm

Journal of Neurology (2022)

-

Challenges in Modeling Hemodynamics in Cerebral Aneurysms Related to Arteriovenous Malformations

Cardiovascular Engineering and Technology (2022)

-

Underlying mechanism of hemodynamics and intracranial aneurysm

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal (2021)

-

Effect of foam insertion in aneurysm sac on flow structures in parent lumen: relating vortex structures with disturbed shear

Physical and Engineering Sciences in Medicine (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.