Abstract

The Przewalski’s horse (Equus ferus przewalskii), the only remaining wild horse within the equid family, is one of only a handful of species worldwide that went extinct in the wild, was saved by captive breeding, and has been successfully returned to the wild. However, concerns remain that after multiple generations in captivity the ecology of the Przewalski’s horse and / or the ecological conditions in its former range have changed in a way compromising the species’ long term survival. We analyzed stable isotope chronologies from tail hair of pre-extinction and reintroduced Przewalski’s horses from the Dzungarian Gobi and detected a clear difference in the isotopic dietary composition. The direction of the dietary shift from being a mixed feeder in winter and a grazer in summer in the past, to a year-round grazer nowadays, is best explained by a release from human hunting pressure. A changed, positive societal attitude towards the species allows reintroduced Przewalski’s horses to utilize the scarce, grass-dominated pastures of the Gobi alongside local people and their livestock whereas their historic conspecifics were forced into less productive habitats dominated by browse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Captive-breeding is often the last resort in efforts to save endangered species, and has been instrumental in saving a handful of species from extinction and returning them to the wild1. One of these species is the Przewalski’s horse (Equus ferus przewalskii), the only remaining wild horse within the equid family2, 3. However, concerns have been raised that captive breeding of endangered wildlife will change morphological, behavioral, or genetic traits ultimately compromising fitness or altering a species functional role in the ecosystem4,5,6. On the other hand, we are also increasingly trying to restore species in a world where ecological conditions have changed or are changing7. Finding a suitable baseline against which to assess the ecology of a reintroduced species is not trivial, particularly when dealing with rare or “extinct in the wild” species which were already subject to anthropogenic pressures even in historic times8.

By the time the Przewalski’s horse became known to the western world in 1881, it had already become restricted to the most remote areas of the Dzungarian Gobi in what is today’s northwest China and southwest Mongolia (Fig. 1, Table 1). The Przewalski’s horse and its close relative the Asiatic wild ass (khulan, Equus hemionus) were targeted as game, persecuted as grazing competitors, and displaced by agriculture9. By the late 1960s, the Przewalski’s horse was extinct in the wild and the khulan had been displaced from the steppe and become entirely confined to the Gobi regions10, 11. In 1992, the first captive bred Przewalski’s horses were returned to the Mongolian Gobi, where some 20 years previously the last wild horses had been observed2 (for history of Przewalski’s horse discovery, extinction and reintroduction see Table 1). The Gobi is still considered part of one of the largest, intact dryland grazing system in the world and has been shared by far ranging ungulates and semi-nomadic livestock herders for millennia12, 13.

Sampling locations and approximate extent of the Przewalski’s horse distribution in the late 19th and early 20th century in what is today’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in northwestern China and Khovd and Gobi-Altai provinces in southwestern Mongolia.? = The exact location of the two historic samples from “Khovd province” (Kobdo) are not known and they may originate from the Depression of the Great Lakes or today’s Great Gobi B SPA. Figure generated in ArcGIS 10.1 (ESRI, Redland, CA, USA, http://www.esri.com/).

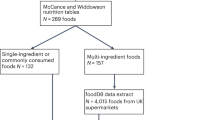

Very little behavioral or ecological data on Przewalski’s horses prior to their extinction in the wild are available. That which exists, comes from a limited number of written historical sources14, 15 or oral accounts of the last eye witnesses16. There are few remaining museum samples of specimens collected in the wild, but these constitute the only additional material available to reconstruct the ecology of Przewalski’s horses prior to extinction17. Stable isotope analysis of animal tissue has become a powerful tool to draw inferences about various aspects of a species’ ecology18. It is particularly useful to address and compare feeding ecology and can make use of a wide variety of samples from ancient, historic, and extant specimens19, 20. In equids, tail hair grows continuously and after formation is metabolically inert, hence constituting a valuable time series archive when sequentially cut and analyzed21,22,23.

We used stable isotope analysis of tail hairs to compare multi-year isotopic diet seasonality and dietary niche characteristics of historic (pre-extinction) and reintroduced (extant) Przewalski’s horses from the Dzungarian Gobi and for comparison did similar analysis for historic and extant sympatric khulan. We reveal a dietary shift from being a mixed feeder in winter and a grazer in summer in the past, to a year-round grazer nowadays, which is best explained by a release from human hunting pressure.

Results

Seasonality in the diet of historic but not reintroduced Przewalski’s horses

The tail hairs of five of the six historic Przewalski’s horses showed a clear seasonality in their δ 13Cdiet profiles. The lowest values were well within the ranges suggesting the primary use of C3 grasses and forbs typical for grazers (>75% grass), but the highest values extended into the value ranges suggesting considerable use of C4 shrubs and semi-shrubs typical for mixed-feeders (25–75% browse) or even browsers (henceforward referred to as “browsing peaks”; Fig. 2).

No seasonality could be observed in any of the six extant Przewalski’s horses, all of which almost entirely stayed within the value range of typical grazers; the same was also true for one of historic Przewalski’s horse. Historic khulan also showed a clear seasonality with low values suggesting grazing and high values suggesting browsing. The pattern was more or less identical to the one previously found in extant animals (Supplementary Fig. S1).

The lack of a precise sampling date did not allow for exact alignment to specific dates in historic samples, but a combination of our examination of coat characteristics and δ 2H seasonality (see Dryad Digital Repository) suggests that browsing peaks in historic Przewalski’s horses and historic khulan coincided with winter and thus follow the same seasonal pattern as has been observed in extant khulan24.

Broader core dietary isotopic niches in historic than extant Przewalski’s horses

Historic Przewalski’s horses had much broader core dietary isotopic niches than reintroduced ones. The size difference is largely due to a much broader spread along the δ 13Cdiet axis; δ 15Ndiet values were somewhat higher, but not broader (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S2). With C4 browse intake showing only narrow peaks, the core dietary isotopic niche is largely positioned within the range of typical grazers, but clearly extends into the range of a mixed feeder. With one exception, individual core isotopic niches were more consistent in shape and larger in size in historic as compared to extant animals (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Khulan, on the other hand, showed highly similar core isotopic niches in historic and extant individuals, both at the pooled (Fig. 3) and the individual level (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Discussion

We detected a clear difference in the isotopic dietary composition between historic and reintroduced Przewalski’s horses. Historic Przewalski’s horses switched from a grazing diet in summer to a mixed grass-browse diet in winter, whereas their reintroduced conspecifics graze year round. Sympatric khulan, on the other hand, showed the same seasonality in their isotopic dietary composition in both historic and extant individuals.

The importance of relearning to optimize foraging behavior in highly seasonal, resource poor environments has been previously demonstrated in captive bred Arabian oryx (Aryx leucoryx) reintroduced to Oman25. However, analysis of forage plant samples from Great Gobi B SPA does not suggest the existence of a nutritional advantage of browse over grasses26 and local domestic horses, which have been free-grazing in the region for centuries, also graze in winter24. Furthermore, equids are considered typical grazers which include browse in their diet only when lacking alternatives27, 28. Hence the diet change between historic and reintroduced Przewalski’s horses suggests a shift from a historic suboptimal diet to a present day more optimal diet, rather than a lack of behavioral adaption among the reintroduced horses.

The human and livestock population in Mongolia has dramatically increased over the last 100 years (Fig. 4), but Mongolia’s Gobi–Steppe ecosystem still remains one of the largest intact expanses of steppe, desert-steppe and desert habitats in the world12. There is also little evidence that C3/C4 plant ratios are influenced by grazing pressure29 and the fact that diets in historic and extant khulan were almost identical further argues against a habitat-induced diet change in Przewalski’s horses.

Living conditions of Przewalski’s horses and khulan in the steppe and desert steppe areas of Mongolia in winter past and present. For supporting references see Supplementary Information S5. Photos: Top left source: Grum-Grzhimailo and Grzhimailo 1896, top right: P. Kaczensky, Artwork: M. van Dalum.

However, Przewalski’s horses and khulan were heavily hunted without restriction until very recently. As a consequence, the effect of humans has likely long been the defining factor in a “landscape of fear”30. Human and livestock presence in Great Gobi B SPA and other parts of the Dzungarian Gobi has always been highly seasonal with local herders leaving in summer and returning in winter31, 32. Herder camps are preferably located in grass-dominated habitats and hence wild equids wary of humans will be displaced into suboptimal shrub habitats in winter, likely also causing a shift in diet towards more browse24. Habitats with tall shrubs like saxaul may also be preferred as they provide better retreats from (legal or illegal) hunting as wildlife are more difficult to spot and chase there.

Nowadays both wild equids are fully protected, but while attitudes towards the newly returned Przewalski’s horse have seen a dramatic change from that of a game species and pasture competitor in historic times to an iconic national flagship species nowadays33, attitudes towards the regionally still numerous khulan remain ambivalent34. For conservation reality on the ground, this means de facto full protection of the newly returned Przewalski’s horse, but continued and significant levels of illegal hunting and harassment for khulan35. As a consequence, extant Przewalski’s horses are rather tolerant of humans, whereas khulan remain wary and avoid the vicinity of herder households36 (Fig. 4).

Extant Przewalski’s horses have to share the habitat with more livestock and humans than ever before, yet the release from human predation pressure allows them year round access to the scarce, grass dominated pastures of the Gobi alongside locals and their livestock (Fig. 4). Thus, not the physical environment, but rather the societal environment has changed with a new positive attitude enabling reintroduced Przewalski’s horses to return to the more “natural” state of being a year round grazer. Conversely, browsing in historic Przewalski’s horses in winter is likely indicative of the historic animals being forced into refuge habitats8 within the same landscape reintroduced Przewalski’s horses again roam. Our results therefore also represent a cautionary tale about using relatively recent historic states as baselines of the pristine. The human displacement effect on extant khulan, on the other hand, appears unchanged and has been documented for other parts of the Gobi as well36. However, khulan seem to be better adapted to exploit low productivity habitats and can also wander further away from water37, 38.

Nevertheless, grass dominated habitats in the Gobi are limited and with a growing Przewalski’s horse population and growing livestock numbers, increasing conflicts with local herders have to be expected32. Future reintroduction initiatives should preferably aim to reestablish Przewalski’s horses on grass dominated steppes, but will have to carefully balance the gain in habitat quality against the reality of ever higher anthropogenic pressures39, 40.

Material and Methods

Study area

At the turn of the 19th century, the distribution range of Przewalski’s horses had become confined to the Dzungarian Gobi and the Depression of the Great Lakes in southwestern Mongolia and today’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous region in northwestern China (Fig. 1). By the 1940’s the species was primarily found in todays’ Great Gobi B SPA in Mongolia where the last sightings occurred in 1968. Reintroduction initiatives eventually prioritized the Great Gobi B SPA as a potential release site and the first transport of captive bred Przewalski’s horses arrived in 199215, 26 (for details of the history of Przewalski’s horses from discovery until reintroduction see Table 1). After initial setbacks, the population started to increase and reached 138 individuals by December 2009. The winter 2009–2010 was extremely harsh, killing millions of livestock throughout Mongolia and causing a crash of the Przewalski’s horse population in the Gobi leaving only 49 individuals alive by spring 201041. Reproduction and additional horse transports have since resulted in the recovery of the population to 167 Przewalski’s horses as of December 2016. The Great Gobi B SPA also houses an estimated 5700 khulan, which have had a continuous presence in the Dzungarian Gobi42.

The habitats of the historic and extant distribution range of the Przewalski’s horse are characterized by an arid, cold-temperate continental climate with a summer precipitation peak (Supplementary Information S3). The landscape consists of desert-steppe, semi-desert, and desert drylands dominated by Chenopodiaceae (shrubs or semi-shrubs like saxaul Haloxylon ammondendron, Anabasis brevifolia, and Salsola sp.) which follow a C4 photosynthetic pathway and Asteraceae (e.g. Artemisia sp. and Ajania sp.), Tamaricaceae (e.g. Reaumuria sp.), and Poaceae (e.g. Stipa sp., Achnatherum splendens, and reed Phragmites sp. forming around larger oases) which follow a C3 photosynthetic pathway43. Alpine meadows above 2000m are primarily dominated by C3 grasses and forbs.

The δ 13C values of 240 plant samples collected by us in 2012 and 2013 followed a bimodal distribution with mean δ 13C value of C3 plants (13 different grass & forb species) of −25.5 ± 1.3‰ (1σ, n = 198, range from −28.9‰ to −22.7‰) and mean δ 13C value of C4 plants (the two shrubs H. ammodendrum & A. brevifolia) of −13.5 ± 0.5‰ (1σ, n = 42, range from −12.6‰ to −14.5‰)24. This subdivision of the dominant vegetation into C3 grasses & forbs and C4 shrubs allows the separation of ungulates into being primarily grazers or browsers from isotopic signatures24.

The Dzungarian Gobi has long been used by semi-nomadic livestock herders, primarily of Mongol or Kazakh origin. Wherever possible, local herders use the Gobi in winter to profit from the warmer temperatures and lower snow coverage, but leave the hot, dry plains in summer for mountain steppe pastures in the adjacent Tien Shan and Altai ranges13, 31. Nowadays population density has increased and land-use intensified dramatically in Xinjiang, but less so in adjacent Mongolia where semi-nomadic pastoralism still remains the key economy in the Gobi region13, 31. To our knowledge, there are no records which allow insight into the movement patterns of historic Przewalski’s horses. The high variation in δ 13C values within individual C3 plants24 and the substantial overlap in the δ 2H values of water sources from the high mountains and the Gobi44 did not allow us to draw conclusions about potential altitudinal or longitudinal migrations in historic equids.

In the Mongolian part of the Dzungarian basin, Przewalski’s horse groups have annual ranges of 152–826 km², whereas khulan roam over area of 4449–6835 km2. However, both species stay in the Gobi year round and both have access to grass as well as shrub dominated plant communities within their annual ranges37. Human infrastructure is minimal in the Mongolian part of the Dzungarian basin and no larger roads or railroads dissect the habitat. The only constrain to human and animal movements is the fenced international border between Mongolia and China45. Przewalski’s horse and khulan have been fully protected in Mongolia since 1930 and 1953 respectively, but illegal killing of certain wildlife, including khulan, remains a problem35.

Sample collection

We obtained historic tail hair samples from six adult Przewalski’s horses and three adult khulan from museum collections at the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg and the Zoological Museum of Moscow Lomonosow State University in Russia (Supplementary Table S1). These historic samples were collected from 1889–1898 in the wild and for 7 out of the 9 samples the location where the animal was killed is known (Fig. 1). For one Przewalski’s horse and one khulan the area of origin is only known as Mongolia’s Khovd province17 and thus samples could originate from either the Dzungarian Gobi or the Depression of the Great Lakes. Samples of extant individuals were collected throughout Great Gobi B SPA in 2009 and 2010 (Fig. 1) and analyzed in a previous study24. Given the large annual ranges of extant wild equids in the Dzungarian Gobi37, historic and extant sampling locations are representative of large surrounding areas.

To allow an approximate alignment of the δ 13C profiles to dates/seasons (not shown) using the average tail hair growth of 0.57mm/day21 a precise collection date is needed, which for historic samples was only available for two individuals (Supplementary Table S1). We thus used overall coat characteristics to at least determine the sampling season (summer coat: May-September, winter coat: November-March; O. Ganbaatar pers. obs.), which was additionally confirmed by the δ 2H values in the corresponding hair (summer: high δ 2H values; winter: low values21). All tails of the museum specimens were still attached to the hide, making species discrimination straight forward. However, according to W. Salensky17 at least one Przewalski’s horse hide had originally been mislabeled “onager [khulan]” and we thus double-checked species identity of all historic Przewalski’s horses using mitochondrial DNA extracted from tail hair samples. The mtDNA analyses in combination with visual inspection confirmed the identification of Przewalski’s horse for all samples (Supplementary Information S4). For the extant samples the exact date of sampling was known and isotope profiles could be assigned to specific dates using methods described by Burnik Šturm et al.21. All tail hairs were sequentially cut into 1 cm increments. Tail hair lengths ranged from 20–49 cm in the six historic Przewalski’s horses and from 32–63 cm in the three historic khulan (Supplementary Table S2), representing approximately 1–2.5 and 1.7–3.2 years of growth in each species, respectively21.

Stable isotope analyses

We conducted stable isotope analysis at the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, Berlin, Germany following methods described in Burnik Šturm et al.21, 24. The precision of measurements was always better than 0.1‰ for δ 13C and δ 15N, and 1.0‰ for δ 2H values, based on repeated analysis of laboratory standards, calibrated with international standards. In the context of this study, δ 2H values were primarily used to assign the δ 13C profiles to the correct seasons (data not shown)21. We corrected all δ 13C results from historic samples by subtracting 1.5‰, the difference in the δ 13C of the atmospheric CO2 between 1900 (−6.8‰)46 and 2009/2010 (−8.3‰)47, to account for the Suess effect caused by burning of fossil fuels over the last 150 years (see Supplementary Table S2 for mean values of raw isotope values by individual). C/N ratios of all tail hair increments ranged between 2.9 and 3.6, indicating high quality sample preservation48.

To convert raw isotope values (δ 13Chair and δ 15Nhair) into diet values (δ 13Cdiet and δ 15Ndiet), we used the dual mixing model of Cerling et al.49. We obtained C3 and C4 end–members from the average δ 13C values (±1 σ) of our 240 plant samples and the diet–hair fractionation factors for horses on a low protein diet50, 51: 2.7‰ for C and 1.9‰ for N. We discriminated between grazer (>75% grass), mixed feeder (26–74% browse), and browser (>75% browse) diets based on the definition of Mendoza and Palmqvist27.

We used a Bayesian approach to estimate species specific core isotopic dietary niches based on bivariate, elipse–based metrics (for δ 13C and δ 15N values) using SIBER implemented in the R package SIAR (Version 4.2)52, 53. We assumed normal distribution based on the large sample size (948 data points) and after visual confirmation of a near normal distribution; although the Shapiro-Wilk multivariate normality test (mshapiro.test) did not formally confirm multivariate normality. Core isotopic niche sizes are expressed as the standard Bayesian ellipse area (SEAB) in ‰2, defined by a subsample containing 40% of the bivariate data. All statistical analyses were conducted in R (version 3.1.1).

Data accessibility

The raw tail hair isotope data can be accessed from Dryad Digital Repository doi:10.5061/dryad.k98k0.

References

Conde, D. A., Flesness, N., Colchero, F., Jones, O. R. & Scheuerlein, A. An Emerging Role of Zoos to Conserve Biodiversity. Science 331, 1390–1391 (2011).

Ryder, O. A. Przewalski’s Horse: Prospects for Reintroduction into the Wild. Conserv. Biol. 7, 13–15 (1993).

Der Sarkissian, C. et al. Evolutionary Genomics and Conservation of the Endangered Przewalski’s Horse. Curr. Biol. 25, 1–7 (2015).

McDougall, P. T., Réale, D., Sol, D. & Reader, S. M. Wildlife conservation and animal temperament: causes and consequences of evolutionary change for captive, reintroduced, and wild populations. Anim. Conserv. 9, 39–48 (2006).

O’Regan, H. J. & Kitchner, A. The effects of captivity on the morphology of captive, domesticated and feral mammals. Mammal Rev. 35, 215–230 (2005).

Williams, S. E. & Hoffman, E. A. Minimizing genetic adaptation in captive breeding programs: A review. Biol. Conserv. 142, 2388–2400 (2009).

Seddon, P. J., Griffiths, C. J., Soorae, P. S. & Armstrong, D. P. Reversing defaunation: Restoring species in a changing world. Science 345, 406 (2014).

Kerley, G. I. H., Kowalczyk, R. & Cromsigt, J. P. G. M. Conservation implications of the refugee species concept and the European bison: king of the forest or refugee in a marginal habitat? Ecography 35, 519–529 (2012).

Heptner, V. G., Nasimovich, A. A. & Bannikov, A. G. Kulan: Equus (Equus) hemionus. 1011–1036 (Mammals of the Soviet Union Volume 1 – Artiodactyla and Perissodactyla. [English translation of the original book published in 1961 by Vysshaya Shkola Publishers Moscow]. Smithsonian Institution Libraries and The National Science Foundation Washington, D.C., USA, 1988).

Kaczensky, P., Lkhagvasuren, B., Pereladova, O., Hemami, M.-R. & Bouskila, A. Equus hemionus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T7951A45171204., doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T7951A45171204.en (2015).

King, S. R. B., Boyd, L., Zimmermann, W. & Kendall, B. E. Equus ferus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T41763A45172856., doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.20152.RLTS.T41763A45172856.en (2015).

Batsaikhan, N. et al. Conserving the World’s Finest Grassland Amidst Ambitious National Development. Cons. Biol. 28 (2014).

Fernandez-Gimenez, M. E. Sustaining the Steppes: A Geographical History of Pastoral Land Use in Mongolia. Geogr. Rev. 89, 315–342 (1999).

Volf, J. Das Urwildpferd (Die Neue Brehm Bücherei, Band 249, Westarp Wissenschaften, Magdeburg, Germany, 1996).

FAO. The Przewalski horse and restoration to its natural habitat in Mongolia. (Recommendations by the FAO/UNEP expert consultation on restoration of Przewalski horse to Mongolia. FAO Animal Production and Health Paper originally published as an FAO/UNEP; http://www.fao.org/docrep/004/AC148E/AC148E00.htm#TOC, 1986).

Sokolow, W. E. et al. Das letzte Przewalskipferdeareal und seine geobotanische Charakteristik (5. Internationales Symposium zur Erhaltung des Przewalskipferdes). Zoologischer Garten Leibzig, 214–218 (1990).

Salensky, W. Prjevalsky’s horse (Equus Prjewalskii Pol.) (Hurst and Blackett Limited, 1907).

Ben-David, M. & Flaherty, E. A. Stable isotopes in mammalian research: a beginner’s guide. J. Mammal. 93, 312–328 (2012).

MacFadden, B. J. Ancient Diets, Ecology, and Extinction of 5-Million-Year-Old Horses from Florida. Science 283, 824–827 (1999).

Sponheimer, M. et al. Using carbon isotopes to track dietary change in modern, historical, and ancient primates. Am. J. Phys. Anthrop 140, 661–670 (2009).

Burnik Šturm, M. et al. A protocol to correct for intra- and interspecific variation in tail hair growth to align isotope signatures of segmentally cut tail hair to a common time line. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 29, 1047–1054 (2015).

Schwertl, M., Auerswald, K. & Schnyder, H. Reconstruction of the isotopic history of animal diets by hair segmental analysis. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 17, 1312–1318 (2003).

Wittemyer, G., Cerling, T. E. & Douglas-Hamilton, I. Establishing chronologies from isotopic profiles in serially collected animal tissues: An example using tail hairs from African elephants. Chem. Geol. 267, 3–11 (2009).

Burnik Šturm, M., Ganbaatar, O., Voigt, C. C. & Kaczensky, P. Sequential stable isotope analysis reveals differences in dietary history of three sympatric equid species in the Mongolian Gobi. J. Appl. Ecol., doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12825 (2016).

Tear, T. H., Mosley, J. C. & Ables, E. D. Landscape-Scale Foraging Decisions by Reintroduced Arabian Oryx. J. Wildlife Manage. 61, 1142–1154 (1997).

Mongolia Takhi Strategy and Plan Work Group. 1993. Recommendations for Mongolia’s takhi strategy and plan (Mongolian government, Ministry of Nature and Environment, Ulaan Baatar, 1993).

Mendoza, M. & Palmqvist, P. Hypsodonty in ungulates: an adaptation for grass consumption or for foraging in open habitat? J. Zool. 274, 134–142 (2008).

Schoenecker, K. A., King, S. R. B., Nordquist, M. K., Nandintsetseg, D. & Cao, Q. Habitat and Diet of Equids In Wild Equids - Ecology, Management, and Conservation (eds Ransom, J. I., Kaczensky, P.) 41–55 (Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, USA, 2016).

Auerswald, K., Wittmer, M. H., Tungalag, R., Bai, Y. & Schnyder, H. Sheep wool delta13C reveals no effect of grazing on the C3/C4 ratio of vegetation in the inner Mongolia-Mongolia border region grasslands. PloS one 7, e45552, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045552 (2012).

Ciuti, S. et al. Human selection of elk behavioural traits in a landscape of fear. Proc. Biol. Sci. B 279, 4407–4416 (2012).

Suttie, J. M. & Reynolds, S. G. Transhumant Grazing Systems in Temperate Asia. FAO Plant Production and Protection Series No. 31 http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/y4856e/y4856e00.htm#Contents (2003).

Kaczensky, P., Enkhsaihan, N., Ganbaatar, O. & Walzer, C. Identification of herder-wild equid conflicts in the Great Gobi B Strictly Protected Area in SW Mongolia. Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia 10, 99–116 (2006).

Bandi, N. & Dorjraa, O. Takhi: Back to the Wild (International Takhi Group, Hustai National Park, Great Gobi B SPA, and Association pout le cheval de Przewalski: TAKH, 2012).

Kaczensky, P. Wildlife Value Orientations of Rural Mongolians. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 12, 317–329 (2007).

Wingard, J. R. & Zahler, P. Silent Steppe: The Illegal Wildlife Trade Crisis (Mongolia Discussion Papers, East Asia and Pacific Environment and Social Development Department. Washington D.C.: World Bank, 2006).

Buuveibaatar, B. et al. Human activities negatively impact distribution of ungulates in the Mongolian Gobi. Biol. Cons. 203, 168–175 (2016).

Kaczensky, P., Ganbaatar, O., von Wehrden, H. & Walzer, C. Resource selection by sympatric wild equids in the Mongolian Gobi. J. Appl. Ecol 45, 1762–1769 (2008).

Zhang, Y. et al. Water Use Patterns of Sympatric Przewalski’s Horse a and Khulan: Interspecific Comparison Reveals Niche Differences. PloS One 10, e0132094, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132094 (2015).

Hoekstra, J. M., Boucher, T. M., Ricketts, T. H. & Roberts, C. Confronting a biome crisis: global disparities of habitat loss and protection. Ecological Letters 8, 23–29, doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00686.x (2004).

Kaczensky, P. et al. Reintroduction of Wild Equids In Wild Equids - Ecology, Management, and Conservation (eds Ransom, J. I., Kaczensky, P.) 196–214 (Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, USA, 2016).

Kaczensky, P. et al. The danger of having all your eggs in one basket–winter crash of the re-introduced Przewalski’s horses in the Mongolian Gobi. PloS One 6, e28057, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028057 (2011).

Ransom, J. I., Kaczensky, P., Lubow, B. C., Ganbaatar, O. & Altansukh, N. A collaborative approach for estimating terrestrial wildlife abundance. Biol. Cons. 153, 219–226 (2012).

Toderich, K., Black, C., Juylova, E. & Kozan, O. C3/C4 plants in the vegetation of Central Asia, geographical distribution and environmental adaptation in relation to climate In Climate Change and Terrestrial Carbon Sequestration in Central Asia (eds Lal, R., Suleimenov, M., Stewart, B. A. Hansen, D. O., Doraiswamy, P.) 33–63 (Taylor & Francis, 2007).

Burnik Šturm, M., Ganbaatar, O., Voigt, C. C. & Kaczensky, P. First field-based observations of δ2H and δ18O values of event-based precipitation, rivers and other water bodies in the Dzungarian Gobi, SW Mongolia. Isotopes Environ. Health Stud 53, 157–171 (2017).

Linnell, J. D. C. et al. Border Security Fencing and Wildlife: The End of the Transboundary Paradigm in Eurasia? PLoS Biol. 14, e1002483, doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002483 (2016).

Rubino, M. et al. A revised 1000 year atmospheric δ13C-CO2 record from Law Dome and South Pole, Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res-Atmos 118, 8482–8499 (2013).

Modern Records of Carbon and Oxygen Isotopes in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide andCarbon-13 in Methane. Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy. http://cdiac.ornl.gov/trends/co2/modern_isotopes.html. Last accessed: April 3, 2016.

O’Connell, T. C., Hedges, R. E. M., Healey, M. A. & Simpson, A. H. R. W. Isotopic Comparison of Hair, Nail and Bone: Modern Analyses. J. Archaeol. Sci. 28, 1247–1255 (2001).

Cerling, T. E. et al. Determining biological tissue turnover using stable isotopes: the reaction progress variable. Oecologia 151, 175–189 (2007).

Ayliffe, L. K. et al. Turnover of carbon isotopes in tail hair and breath CO2 of horses fed an isotopically varied diet. Oecologia 139, 11–22 (2004).

Sponheimer, M. et al. Nitrogen isotopes in mammalian herbivores: hair δ 15N values from a controlled feeding study. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol 13, 80–87 (2003).

Jackson, A. L., Inger, R., Parnell, A. C. & Bearhop, S. Comparing isotopic niche widths among and within communities: SIBER - Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses in R. J. Anim. Ecol 80, 595–602 (2011).

Parnell, A. C., Inger, R., Bearhop, S. & Jackson, A. L. Source partitioning using stable isotopes: coping with too much variation. PloS One 5, e9672, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009672 (2010).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to K. Grassow, A. Luckner, and Y. Klaar for isotope analyses, D. Fichte for sample preparation, and J.D.C. Linnell for comments and corrections on the manuscript. This study was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) grant P24231. Samples were imported to Austria in accordance with the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES import permits AT 15-E-0993, AT 15-E-0994) and with the respective veterinary permit (No. 01637/15–3.11.2015). There is no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.K.: Study design, extant equid ecology, manuscript writing, preparation of Table 1, Figures 1–4 & Supplementary Figures S2, S3; M.B.Š.: Isotope analysis design, data analysis and statistics, preparation of Figures 2–3 & Supplementary Figures S1–S4, input to and review of manuscript; M.V.S.: Access to historical samples, input to manuscript; C.C.V.: Isotope analysis facility and input to manuscript, S.S.: Genetic facility and input to manuscript, preparation of Supplementary Information S4; O.G.: Background on reintroduced Przewalski’s horses, sampling and logistics in Great Gobi B SPA; B.B.: Genetic analysis including refinement of methods for historic hair samples for Supplementary Information S4; C.W.: Background on reintroduced Przewalski’s horses, sampling extant khulan, input to manuscript; N.N.S.: Organization of museum samples in Russia, background information on historic Przewalski’s horses, input to manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaczensky, P., Burnik Šturm, M., Sablin, M.V. et al. Stable isotopes reveal diet shift from pre-extinction to reintroduced Przewalski’s horses. Sci Rep 7, 5950 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05329-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05329-6

This article is cited by

-

Linking diet switching to reproductive performance across populations of two critically endangered mammalian herbivores

Communications Biology (2024)

-

Functional traits of the world’s late Quaternary large-bodied avian and mammalian herbivores

Scientific Data (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.