Abstract

Plant pathogenic bacteria exerts their pathogenicity through the injection of large repertoires of type III effectors (T3Es) into plant cells, a mechanism controlled in part by type III chaperones (T3Cs). In Ralstonia solanacearum, the causal agent of bacterial wilt, little is known about the control of type III secretion at the post-translational level. Here, we provide evidence that the HpaB and HpaD proteins do act as bona fide R. solanacearum class IB chaperones that associate with several T3Es. Both proteins can dimerize but do not interact with each other. After screening 38 T3Es for direct interactions, we highlighted specific and common interacting partners, thus revealing the first picture of the R. solanacearum T3C-T3E network. We demonstrated that the function of HpaB is conserved in two phytopathogenic bacteria, R. solanacearum and Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria (Xcv). HpaB from Xcv is able to functionally complement a R. solanacearum hpaB mutant for hypersensitive response elicitation on tobacco plants. Likewise, Xcv is able to translocate a heterologous T3E from R. solanacearum in an HpaB-dependent manner. This study underlines the central role of the HpaB class IB chaperone family and its potential contribution to the bacterial plasticity to acquire and deliver new virulence factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ralstonia solanacearum species complex (RSSC), the causal agent of bacterial wilt, is divided into four phylotypes (I, II, III and IV), corresponding to different geographical origins of the strains1. This devastating plant pathogenic bacterium harbors an unusually large host range as RSSC strains infect more than 250 plant species, including important food crops such as tomato, potato, banana or eggplant, but also model plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana and Medicago truncatula 2, 3. This soilborne pathogen enters into the plant via the roots, colonizes the xylem vessels and then blocks plant water flow driving to wilting symptoms4. Beyond the huge arsenal of pathogenicity determinants including exopolysaccharides, plant cell wall degrading enzymes, attachment proteins, and phytohormones, the type III secretion system (T3SS) appears as the main determinant of the bacterial virulence5. Indeed, mutants in the genes encoding the T3SS are unable to cause an hypersensitive response (HR) or disease symptoms on host plants4.

T3SSs are molecular syringes that allow the injection of bacterial proteins, called type III effectors (T3Es), into the plant cytosol6. T3SSs are very well conserved in many plant pathogenic bacteria such as Xanthomonas spp., Pseudomonas syringae or Erwinia amylovora and in animal and human pathogenic bacteria6. In phytopathogenic bacteria, the T3SS proteins are encoded by genes located in the hrp (hypersensitive response and pathogenicity) gene cluster. The hrp clusters are grouped into two families. Hrp1 organization clusters are mostly found in P. syringae and E. amylovora, while Hrp2 clusters are found in R. solanacearum and X. campestris 7.

R. solanacearum is widely used as a model to study plant-bacteria interactions and has been ranked as the second most important bacterial plant pathogen based on scientific/economic importance8. When compared with T3E repertoires of other model phytopathogenic bacteria: P. syringae (20 to 30 T3Es)9, Xanthomonas spp. (≈40 T3Es)10, and Erwinia spp. (10 to 15 T3Es)11, the mean repertoire in RSSC strains is larger (48 to 76 T3Es), with a pan-effectome currently comprising 113 T3Es, called Rip for Ralstonia injected proteins12. The primary function of T3Es is to hijack plant defenses and to allow bacterial disease development by suppressing plant immunity as well as interfering with plant hormone regulations or plant cellular functions13. Alternatively, T3Es can be directly or indirectly recognized by plant resistance proteins, or can activate resistance gene expression, triggering strong plant defenses, leading to the plant resistance13. This is the case for the R. solanacearum effectors RipAA and RipP1 (formerly named AvrA and PopP1), that induce an HR on Nicotiana species14. The R. solanacearum GMI1000 strain used in this study possesses 72 Rips12, 15. Although many studies have revealed transcriptional control mechanisms of type III secretion5, less information is available concerning the post-translational control of T3E secretion.

In plant and animal pathogenic bacteria, two families of proteins have an essential role in type III secretion: the type III chaperones (T3Cs) and the T3S4 (type III secretion substrate specificity switch) proteins. These proteins regulate T3E secretion at post-transcriptional and post-translational levels. They contribute to stabilize and favor the delivery of T3Es into host cells and specifically interact with T3Es, but the importance of these interactions to the secretion process is still not well characterized. It is only hypothesized that these bodyguard proteins may prevent premature interactions of their specific substrates, possibly through binding16, 17. It is also described that T3Cs facilitate the directionality and binding of their targeted substrates to components of the secretion apparatus, in particular to the ATPase which energizes the protein translocation through the T3SS18,19,20. T3Cs are generally small and acidic proteins that often interact as homo- or heterodimers with their cognate substrates. These T3Cs either modulate the secretion of one single associated effector (class IA chaperones), several T3Es (class IB chaperones), or the translocon proteins that insert into the host plasma membrane (class II chaperones)6, 17, 21. T3S4 proteins interact with the cytoplasmic domains of YscU/HrcU family members (i.e. Yersinia YscU, or Xanthomonas HrcU family members)22, 23 to regulate substrate specificity, in particular allowing the switch between early substrates (including architectural elements of the T3SS) and late substrates (translocon proteins and T3Es)6, 24,25,26. T3S4 proteins interact also with T3Es, but the functional importance of this interaction remains unknown25. Up to now, Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria 85–10 (called Xcv 85-10 hereafter) is the bacterium for which T3E bodyguards are the best described, especially the HpaB T3C and the T3S4 protein HpaC18, 25, 27,28,29,30,31. In R. solanacearum, secretion helper proteins are called Hpa for Hypersensitive response and pathogenicity associated proteins. In our previous work, we compared the secretomes of the GMI1000 strain with several hpa mutants15. We showed that the candidate T3Cs studied were playing different roles in T3E secretion. HpaB is required for the secretion of the majority of the T3Es, whereas HpaD is involved in the control of the secretion of few T3Es. We also observed that both proteins are not implicated in T3E stabilization in the bacterial pellets15. Up to date, little is known about functional interactions between R. solanacearum Hpa proteins and T3Es. Our previous research demonstrated that the T3S4 protein HpaP was able to specifically interact with one T3E, RipP132. Here, we investigate the function of two candidate chaperones, HpaB and HpaD, in the post-translational control of R. solanacearum T3Es. We show that HpaB and HpaD are class IB chaperones interacting with numerous T3Es, and we highlight shared and specific partners. We also studied the role of HpaB in the bacterial virulence. To gain further insights into a potential conserved role of HpaB protein family among the Hrp2 T3SS cluster, the hpaB gene from Xcv 85-10 was expressed in the R. solanacearum hpaB mutant. Xcv is the causal agent of bacterial spot disease on pepper and tomato, and has a completely different infectious cycle compared to R. solanacearum, entering the plant through stomata or wounds to reach the intercellular spaces33. Interestingly, we provide evidence of a functional complementation of the R. solanacearum hpaB mutant, by its Xcv 85-10 counterpart through T3E secretion assays and the ability to induce specific plant responses. On the other hand, we also show that Xcv 85-10 is able to translocate a heterologous R. solanacearum T3E, highlighting the existence of structurally conserved mechanisms between two phytopathogenic bacteria exhibiting different lifestyles.

Results

HpaB and HpaD: two putative type III chaperones conserved among the four phylotypes of R. solanacearum species complex

The hpaB gene from R. solanacearum GMI1000 is localized within the hrp gene cluster and the hpaD gene is localized on the left border end of the cluster (Fig. 1a). Both genes are conserved among all the sequenced strains of the RSCC. We generated an amino acid conservation matrix table between HpaB, HpaD and HrcV from GMI1000 and other sequenced strains belonging to all the four phylotypes of the RSSC (Fig. 1b). HrcV, a structural core component of the T3SS highly conserved in plant and animal pathogenic bacteria carrying a T3SS, is one of the most conserved protein among the hrc (hrp conserved)/hrp gene cluster (Fig. 1b). The candidate T3C HpaB is highly conserved among the 11 strains, with a higher level of overall sequence identity compared to HrcV proteins (almost 100% identity between strains from phylotypes I, II and III). HpaB is also conserved outside the Ralstonia species since HpaB homologs are found in Hrp2 T3SS plant-pathogenic bacteria such as, Xanthomonas spp. e.g. Xcv 85-10 (50.67% identity), Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae KACC10331 (64.97% identity), or Acidovorax citruli AAC00-1 (74% identity) (Supplementary Fig. S1). The candidate T3C HpaD is also present in the four phylotypes of the RSSC. Although it shows 100% identity between strains from phylotypes I and III, it reaches 85% with strains from phylotype IV, and decreases to around 75% with strains from phylotypes IIA and IIB (Fig. 1b). HpaD homologs were found in other Ralstonia species such as R. mannitolilytica SN83A39 (57.49% identity) or in other uncharacterized Ralstonia species (54.03% identity in Ralstonia sp. A12). HpaD homologs are found only in close related species such as Burkholderiaceae sp. (31.2% identity in Burkholderiaceae bacterium 26) (Supplementary Fig. S2). Phylogenetic analysis of HpaD proteins reveals a perfect match with the RSSC phylogeny separating the four phylotypes (Fig. 1c).

HpaB and HpaD: two putative type III chaperones, encoded by genes located on the hrp gene cluster, are conserved among all the four phylotypes of the R. solanacearum species complex (RSSC). (a) Schematic representation of the RSSC hrp gene cluster. The arrows represent the different genes. The green, blue, red and yellow color indicates the hpa, prh, hrp and hrc genes, respectively. (b) Protein identity matrix table of HrcV, HpaB and HpaD from nine RSSC sequenced strains belonging to the four phylotypes compared to the GMI1000 (phylotype I) strain. Matrix cells have been colored from orange to yellow according to the protein conservation (100% orange to 70% yellow). Xcv: Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. (c) Unrooted phylogenetic tree of HpaD based on sequence similarities using the maximum likelihood method. Ten strains of RSSC were used. Bootstraps were calculated using the approximate likelihood ratio test. The phylogenic tree has been generated using MEGA software.

HpaB, but not HpaD, is required for R. solanacearum pathogenicity on tomato plants

We evaluated the role of the hpaB and hpaD mutations on R. solanacearum pathogenicity on tomato plants. First, we checked that the mutants were not affected in growth. For that purpose, we compared the in vitro growth kinetics of the hpaB and hpaD mutants with the wild-type strain in complete medium and in minimal medium supplemented with glutamate by monitoring OD600nm over 25 hours (Supplementary Fig. S3a,b). No significant differences were observed between the three strains in both media. Tomato plants were then root inoculated using the hpaB and the hpaD mutants and plants survival was monitored daily and compared to the GMI1000 wild-type strain inoculation. The hpaB mutant was unable to induce disease on tomato, a phenotype complemented by an ectopic copy of the hpaB gene (Supplementary Fig. S3c). On the other hand, HpaD was found to be dispensable for disease establishment on tomato plants, the hpaD mutant being able to trigger disease symptoms as the wild-type strain (Supplementary Fig. S3d).

HpaB and HpaD self-interact but do not interact with each other

We wondered whether candidate T3Cs HpaB and HpaD exhibit known chaperone properties like self-dimerization or if they could act together in the control of type III secretion. Thus, we investigated their ability to self-interact or to interact with each other. Yeast two-hybrid assays were performed using the binding domain (BD) and the activation domain (AD) of the transcription factor GAL4 as fusion partners with HpaB and HpaD. In the case of an interaction between BD- and AD- fusion proteins, yeasts are able to grow on a minimal medium lacking histidine. First, yeasts were co-transformed with the vectors encoding BD-HpaB or BD-HpaD and AD-HpaB or AD-HpaD. BD-p53 and AD-T-antigen were used as controls, both as positive control (BD-p53/AD-T-Ag interaction is visualized with a yeast growth on minimal medium lacking histidine) and as negative control. Indeed, yeasts co-transformed with BD- and AD- (HpaB or HpaD) constructs and one of these controls do not grow on minimal medium lacking histidine (Fig. 2a). This indicated that HpaB and HpaD do not autoactivate in yeast. We observed that HpaD was able to self-interact, while no interaction could be detected between HpaB-HpaB and HpaD-HpaB (Fig. 2a). Then, we looked for potential interactions between these candidate T3Cs using another method. We performed glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down assays: GST, GST-HpaB, GST-HpaD fusion proteins were immobilized on glutathione sepharose matrix, and incubated with 6His-HpaB (Fig. 2b) or 6His-HpaD (Fig. 2c). Eluates were analyzed using anti-GST and anti-6His specific antibodies. We were able to detect 6His-HpaB in the presence of GST-HpaB, but not with GST alone (Fig. 2b). Same results were obtained when incubating 6His-HpaD with GST-HpaD (Fig. 2c). 6His-HpaD was not detected when incubated with GST-HpaB (Fig. 2c). All together, these results suggest that both HpaB and HpaD can self-interact whereas HpaB and HpaD do not physically interact.

HpaB and HpaD self-interact but do not interact with each other. (a) Yeast cells were co-transformed by BD-HpaB or BD-HpaD and AD-HpaB or AD-HpaD. Double transformation and interaction were tested by plating yeasts on synthetic dropout medium lacking leucine and tryptophan (SD/–Leu/–Trp) and synthetic dropout medium lacking leucine, tryptophan and histidine (SD/–Leu/–Trp/–His), respectively. BD-p53 and AD-T-antigen were used as controls, together as a positive control (BD-p53/AD-T-Ag interaction is visualized with a yeast growth on minimal medium lacking histidine) and for tested interactors as negative controls. (b) Glutathione S-transferase (GST), GST-HpaB or GST-HpaD were immobilized on glutathione sepharose and incubated with an E. coli lysate containing 6His-HpaB or 6His-HpaD. Total cell lysates and eluted proteins were analysed using antibodies directed against GST and the 6His epitope. Bands corresponding to GST and GST fusion proteins are marked by asterisks. Lower bands represent degradation products. Two biological replicates were performed for (a) and (b) with similar results.

HpaB and HpaD each interact with several structurally unrelated T3Es

We tested whether HpaB and HpaD act on T3E secretion by direct interactions. Using the yeast two-hybrid method, we screened for HpaB and HpaD interactions with 38 R. solanacearum T3Es differing in their secretion patterns (from high to intermediate and low levels of secretion, or not detected)15. Candidate T3Cs were fused to the binding domain of the GAL4 transcription factor whereas the T3Es were fused to the activation domain. As previously described, we used BD-p53 and AD-T-Ag as control vectors32. Because yeasts co-transformed with BD-p53 and AD-RipP2 were able to grow on minimal medium lacking histidine, indicating GAL4 promoter autoactivation in our conditions, we were not able to conclude for HpaB- or HpaD-RipP2 interactions (Figs 3a and 4a). We didn’t detect any autoactivation for the other T3Es tested. Among 37 T3Es-HpaB interactions tested, HpaB was found to interact with nine T3Es, RipG4, RipP1, RipAW, RipTPS, RipAF1, RipO1, RipAK, RipG5 and RipG1, while no interaction was detected for 28 T3Es (Supplementary Table S1). In order to validate these yeast two-hybrid data, we performed GST pull-down experiments with the nine T3Es identified, with RipP2 (as no conclusion could be taken with yeast experiments), and with RipW and RipG7 as negative based on yeast two-hybrid assays. We tested 6His-HpaB in the presence of GST-T3Es. We were not able to express RipG4 as GST-fusion in E. coli. HpaB was not eluted when incubated with the GST, meaning that HpaB alone does not bind to the GST epitope or to the matrix (Fig. 3b). We were able to identify and confirm a positive interaction with HpaB for RipP1, RipTPS, RipAF1, RipAK, RipG5 and RipG1. A weak signal was visualized for RipAW, suggesting a potential weaker interaction with HpaB. Interestingly, we also revealed a RipP2-HpaB interaction. No signal was observed with RipO1, nor with RipW and RipG7 (Fig. 3b). Same experiments were carried out with the HpaD candidate T3C. First, using yeast two-hybrid assays, among 37 T3Es-HpaD interactions tested, HpaD was found to interact with eight T3Es, RipG4, RipP1, RipAW, RipTPS, RipAF1, RipO1, RipTAL and RipAV, while no interaction was detected for 29 T3Es (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table S1). We then proceeded as previously to run GST pull-down experiments. Because of toxicity in E. coli we were not able to express RipTAL as GST-fusion. We were able to identify and confirm a positive interaction with HpaD for RipP1, RipTPS, RipAF1, RipAV, and to highlight an interaction with RipP2. A weak signal was also visualized for RipAW. No signal was observed with RipO1, nor RipW and RipG7 (Fig. 4b).

R. solanacearum HpaB interacts with nine type III effectors. (a) Yeast cells were co-transformed by BD-HpaB and 38 AD-T3Es. Double transformation and interactions were tested by plating yeasts on synthetic dropout medium lacking leucine and tryptophan (SD/–Leu/–Trp) and synthetic dropout medium lacking leucine, tryptophan and histidine (SD/–Leu/–Trp/–His), respectively. RipW and RipG7 have the same profile as 26 other T3Es tested. BD-p53 and AD-T-antigen were used as negative controls. Three biological replicates were performed and gave same results. (b) Glutathione S-transferase (GST) and GST-T3Es were immobilized on glutathione sepharose and incubated with an E. coli lysate containing 6His-HpaB. Total cell lysates and eluted proteins were analyzed using antibodies directed against GST and the 6His epitope. Bands corresponding to GST and GST fusion proteins are marked by asterisks; lower bands represent degradation products. For lack of space, samples have been loaded into two gels (black line separation). The experiments have been repeated twice with similar results.

R. solanacearum HpaD interacts with eight type III effectors. (a) Yeast cells were co-transformed by BD-HpaD and 38 AD-T3Es. Double transformation and interactions were tested by plating yeasts on synthetic dropout medium lacking leucine and tryptophan (SD/–Leu/–Trp) and synthetic dropout medium lacking leucine, tryptophan and histidine (SD/–Leu/–Trp/–His), respectively. RipW and RipG7 have the same profile as 27 other T3Es tested. BD-p53 and AD-T-antigen were used as negative controls. Three biological replicates were performed and gave same results. (b) Glutathione S-transferase (GST) and GST-T3Es were immobilized on glutathione sepharose and incubated with an E. coli lysate containing 6His-HpaD. Total cell lysates and eluted proteins were analyzed using antibodies directed against GST and the 6His epitope. Bands corresponding to GST and GST fusion proteins are marked by asterisks; lower bands represent degradation products. For lack of space, samples have been loaded into two gels (black line separation). The experiments have been repeated twice with similar results.

The hpaB gene from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria can complement the R. solanacearum hpaB mutant for HR elicitation on tobacco plants

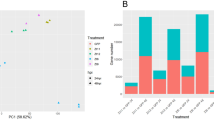

We then conducted a functional characterization of HpaB, as we demonstrated that the protein interacts with numerous effectors, and its defect strongly affects T3E secretion and bacterial pathogenicity. We thus wondered if HpaB could harbor a conserved function among Hrp2 T3SS plant pathogenic bacteria. To study the potential generalist function of HpaB, we generated a strain with a chromosomic insertion of hpaB Xcv 85-10 into the R. solanacearum hpaB mutant. The wild-type strain, the hpaB mutant and the hpaB mutant complemented with the GMI1000 allele (hpaB::hpaB Rs GMI1000) or the Xcv 85-10 allele (hpaB::hpaB Xcv 85-10) were infiltrated into Nicotiana tabacum leaves at 108 and 107 CFU/mL. As previously described, the wild-type strain GMI1000 triggers a full HR at 107 and 108 CFU/mL14. The hpaB mutant does not trigger any HR at both concentrations, and the hpaB mutant complemented with hpaB Rs GMI1000 allele restores a full HR at 107 and 108 CFU/mL. Interestingly, complementation with hpaB Xcv 85-10 allele restores a full HR at 108 CFU/mL and a partial HR at 107 CFU/mL (Fig. 5a). The same strains were used to root inoculate tomato plants. While the hpaB Rs GMI1000 allele fully complement the hpaB mutation, we observe no disease symptoms with the hpaB Xcv 85-10 allele (Fig. 5b and c).

The hpaB gene from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria (Xcv) 85–10 can complement the R. solanacearum hpaB mutant to trigger an hypersensitive response (HR) on tobacco plants, but not for disease establishment on tomato plants. (a) N. tabacum leaves were infiltrated with R. solanacearum bacterial suspensions at 108 CFU/ml (upper part) and 107 CFU/ml (lower part), using the GMI1000 wild-type strain, the hpaB mutant (GMI1000 background), the hpaB mutant complemented with the hpaB gene from R. solanacearum GMI1000 and the hpaB mutant complemented with the hpaB gene from Xcv 85-10. Pictures were taken 24 h post infiltration. The dotted lines represent the infiltrated areas. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. (b) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of 16 tomato plants per R. solanacearum strain root inoculated. Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test indicates that the wild-type strain curve (red) is significantly different from the hpaB mutant curve (blue) (p-value < 0.001), and to the curve showing the hpaB mutant complemented with the Xcv 85-10 hpaB gene (p-value < 0.001). The wild-type strain curve (red) is not significantly different from the curve showing the hpaB mutant complemented with R. solanacearum GMI1000 hpaB gene (dotted cyan) (p-value = 0.0678). Three biological repeats were performed with similar results. (c) Representative pictures showing the tomato responses six days after inoculation of the R. solanacearum hpaB mutant complemented with the hpaB genes isolated from R. solanacearum GMI1000 (left) or Xcv 85-10 (right). Experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

Defective secretion of RipP1 and RipP2 in a R. solanacearum hpaB mutant is partially restored by the X. campestris pv. vesicatoria hpaB gene

To study the contribution of a cis-encoded HpaB from Xcv 85-10 on effector secretion in a R. solanacearum hpaB mutant, we performed secretion assay experiments, growing in T3-inducing conditions the five following strains: the GMI1000 wild-type strain, the hrcV mutant (a T3 defective mutant used as a negative control), the hpaB mutant and both complemented strains hpaB::hpaB Rs GMI1000 and hpaB::hpaB Xcv 85-10. Supernatants and cell pellets were harvested and analyzed using specific anti-T3E antibodies. We observed the secretion of five well described T3Es: RipX, RipG7, RipAA, RipP1 and RipP2. Silver staining showed that the same amount of proteins was loaded in each lane. All the five T3Es were detected in same amount in the cell pellets (Fig. 6a). As expected, no T3E was detected in the supernatant of the hrcV mutant, indicating no detectable lysis in our samples. As shown in our previous work, specific secretion patterns were observed for the hpaB mutant15. Indeed, we observed a wild-type secretion of RipX, a partial secretion of RipG7 and no secretion of RipAA, RipP1 and RipP2. T3E secretion was restored in the hpaB::hpaB Rs GMI1000 strain. Interestingly, the hpaB::hpaB Xcv 85-10 strain was able to partially restore the secretion of RipP1 and RipP2, while the secretion level of RipAA and RipG7 was similar as in the hpaB mutant (Fig. 6a). To confirm the physiological relevance for RipP1 secretion in hpaB::hpaB Xcv 85-10 complemented strain, we first looked whether HpaB Xcv could interact with the R. solanacearum T3E RipP1 in GST pull-down experiments using HpaB Xcv fused to a 6His epitope tag and RipP1 to a GST epitope tag. HpaB Xcv was eluted when incubated with the GST-RipP1, but not with GST alone (Fig. 6b), suggesting a possible HpaB Xcv - RipP1 interaction.

HpaB Xcv can functionally control RipP1 secretion/translocation in R. solanacearum and in X. campestris pv. vesicatoria and is able to bind RipP1. (a) Lack of secretion of RipP1 and RipP2 in R. solanacearum hpaB mutant is partially restored when complementing with the Xcv 85-10 hpaB gene. R. solanacearum secretion assays were performed in type III inducing conditions, for the GMI1000 wild-type strain, the hrcV mutant, the hpaB mutant and the hpaB mutant complemented with the hpaB gene from R. solanacearum GMI1000 or the hpaB gene from Xcv 85-10. Total proteins from bacterial pellets and supernatants were analyzed by Western-blot using specific antibodies or total proteins were stained by silver nitrate. (b) HpaB Xcv binds R. solanacearum RipP1 T3E. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) and GST-RipP1 were immobilized on glutathione sepharose and incubated with an E. coli lysate containing 6His-HpaB Xcv . Total extract (TE) and eluted proteins were analyzed using antibodies directed against the 6His epitope and GST respectively. Bands corresponding to GST and GST fusion protein are marked by asterisks. (c) RipP1 R. solanacearum T3E is heterogously translocated by Xcv, in an HpaB dependent manner. For this experiment, the wild-type strain Xcv 85-10 (85*) and the hpaB Xcv mutant (85*ΔhpaB) both carry hrpG*, a mutated version of the key regulatory gene hrpG in the bacterial chromosome (Büttner et al., 2004). Xcv 85* and 85*ΔhpaB strains, and derivatives containing RipP1-AvrBs3Δ2 construct, were infiltrated into leaves of ECW-10R (carrying Bs1 resistance gene) and ECW-30R (carrying Bs3 resistance gene) pepper plants. Bacteria were infiltrated at OD600 of 0.2 (corresponds to 2 × 108 cfu/ml). Leaves were bleached 2 dpi for better visualization of the HR. Dashed lines indicate the infiltrated areas. For protein analysis, bacteria were grown ON in NYG medium. Equal amounts of cell extracts (adjusted according to OD) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting, using an AvrBs3-specific antibody. For (a), (b) and (c), two biological replicates were done with similar results.

X. campestris pv. vesicatoria is able to translocate R. solanacearum RipP1 effector, in a HpaB-dependent way

We next investigated whether HpaB Xcv could function as a chaperone for R. solanacearum RipP1 T3E, by examining if RipP1 could be translocated by Xcv 85-10. For these experiments, we used the strains 85* and 85*ΔhpaB carrying the hrpG* mutation, which confers constitutive activation of the HrpG regulator and, in turn, constitutive expression of the T3SS34. We fused RipP1 to the reporter protein AvrBs3Δ2, a derivative of the effector protein AvrBs3 lacking its translocation signal35. RipP1-AvrBs3Δ2 fusion construct was then transformed into the strains 85* and 85*ΔhpaB. AvrBs3Δ2 contains the effector domain triggering HR in the resistant pepper line ECW-30R carrying the Bs3 resistance gene36 and the fusion protein generated was used to monitor R. solanacearum RipP1 translocation in planta. First, we checked that the 85* strain, but not the 85*ΔhpaB mutant, induces the AvrBs1-specific HR when inoculated into the leaves of the AvrBs1-responsive ECW-10R pepper plants37. This indicated that RipP1-AvrBs3Δ2 do not interfere with the activity of the T3SS (Fig. 6c). As a second control experiment, we confirmed that after infiltration in ECW30R pepper, 85* strain and 85*ΔhpaB mutant do not trigger an HR. Interestingly, after infiltration of the strains carrying RipP1-AvrBs3Δ2 constructs, we observed an HR in ECW-30R pepper plants when delivered by the 85* strain, but not in the 85*ΔhpaB mutant (Fig. 6c). Similar amounts of RipP1-AvrBs3Δ2 were detected by immunoblot in total cell extracts for each strain (Fig. 6c), suggesting that the lack of protein translocation by 85*ΔhpaB mutant was not due to reduced protein stability. All these data show that Xcv 85-10 is able to translocate a R. solanacearum T3E, and remarkably, this heterologous translocation is dependent on the HpaB Xcv class IB chaperone.

Discussion

In R. solanacearum, HpaB and HpaD were considered as candidate type III chaperones, based on their structural features, their T3-dependent regulation and their requirement for T3E secretion15. Both modulate T3E secretion at different levels, but we did not know their roles in terms of functional interactions. In this study, we demonstrated that HpaB and HpaD are bona fide R. solanacearum class IB chaperones as (i) both are able to form dimeric complexes; and (ii) HpaB and HpaD directly interact with at least ten and nine T3Es, respectively. Moreover, we highlighted seven T3Es as shared interactors while some were demonstrated to interact more specifically, either with HpaB, or HpaD (Fig. 7). Hence, to our knowledge, this study depicts the widest known T3C-T3E interaction network in a phytopathogenic bacterium, validated using two biochemical interaction assays. The homodimerization observed for both studied Hpa proteins is a key feature of numerous T3C-T3E complexes38. T3C-T3E interactions were well described in animal and plant pathogenic bacteria, where T3Cs are often clustered with the targeted T3E (Class IA chaperones)21. Class IB chaperones have been extensively studied in mammal pathogenic bacteria such as Spa15 of Shigella flexneri 39, InvB of Salmonella enterica 40, 41, or CesT of Escherichia coli 42,43,44, which each bind to several effectors. In plant pathogenic bacteria, only the HpaB protein, identified specifically in Hrp2 group7, has been described as a class IB chaperone in the genus Xanthomonas 6. HpaB is conserved in all Xanthomonas species45 and is required for full pathogenicity in X. axonopodis pv. glycines 45, X. oryzae pv. oryzae 46 and X. campestris pv. vesicatoria 27. Several studies in Xanthomonas spp. demonstrated that HpaB is important for T3E secretion/translocation27, 28, 47, 48. In Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri, a direct interaction was reported with a T3S substrate, HpaA, and with the C-terminal cytosolic domain of HrcV49. In X. campestris pv. vesicatoria, HpaB protein interacts with three T3Es, but also with a wide range of non-T3E substrates, such as the inner membrane proteins HrcU and HrcV, the ATPase HrcN, and other T3S control proteins18, 27, 28, 50,51,52,53. In R. solanacearum, hpaB and hpaD are physically linked to the hrp gene cluster, suggesting a common evolutionary history. Here, we demonstrated for the first time that both are involved in numerous direct interactions with R. solanacearum T3Es.

Type III interactome for HpaB and HpaD, two Class IB chaperones of R. solanacearum exhibit shared and specific T3E partners. This model shows that HpaB and HpaD are able to self-interact, and to interact with numerous T3Es. Solid black lines indicate interactions that have been confirmed by yeast two-hybrid and GST pull-down assays. Dotted black lines indicate interactions that have been identified by one of these two methods. The HpaB-HpaD interacting assays were negative with both methods. The model has been drawn using Cytoscape software.

R. solanacearum HpaB protein appeared to have a more central role. HpaB was previously shown to be required for the efficient secretion and translocation of many R. solanacearum T3Es15, 54. In our previous work15, we highlighted three different levels of HpaB-involvement for T3E secretion: (1) T3Es secreted in an HpaB-independent way; (2) T3Es for which secretion is partially dependent on HpaB; and (3) T3Es secreted in a strict HpaB dependency. For T3Es belonging to the two first classes (for RipW, RipAM and for RipG7, respectively), no interaction was observed. Otherwise, all the T3Es identified as HpaB-interactors are strictly dependent on HpaB for their secretion (RipG5, RipP1, RipP2, RipAF1 and RipAK). Hence, these data reinforce the HpaB-independent T3S pattern for the first classes of substrates. For the other T3Es, whose secretion is HpaB-dependent, numerous direct interactions have been highlighted. Among the large number of T3Es requiring HpaB for their secretion15, at least 28 T3Es were not identified as direct HpaB-interactors in this study. Because it is known that a major limiting factor of yeast two-hybrid is the false negative rate of the assays55, we cannot exclude the occurrence of such false negative interactions in our experiments and that consequently a large part of these 28 T3Es may be indirectly controlled by HpaB. We can hypothesize that these 28 T3Es may be indirectly controlled by HpaB for their secretion, involving other chaperones or uncharacterized co-factors. Moreover we cannot exclude that HpaB controls T3E secretion through interactions with structural components of the T3SS. Otherwise, while HpaB and HpaD share several interacting partners, we could not identify a direct HpaB-HpaD interaction, using two different techniques. Other studies described that two T3Cs could interact with the same translocon protein56,57,58. To our knowledge, we describe here the first example of two T3Cs interacting with the same T3Es (seven common interactors identified). However, their implication in R. solanacearum pathogenicity is different. We demonstrated that HpaB is strictly required for disease establishment and to trigger an HR on tobacco plants. This is explained by the defect of the secretion of numerous T3Es in the hpaB mutant15. Differently, even if binding to at least nine T3Es, we previously observed for the hpaD mutant a secretion pattern close to the wild-type strain, and we were not able to see an implication of HpaD on bacterial pathogenicity of R. solanacearum GMI100015. The hpaD gene seems to be restricted to Ralstonia species or to very close related species. In the RSSC, we saw that HpaD sequences diverged into two distinct phylogenetic groups. We can hypothezise that HpaD could have a more important role in other strains belonging to phylotype II or IV or could be important for pathogenicity on specific hosts. Its exact function remains to be elucidated.

The R. solanacearum HpaB protein sequence is highly conserved among the RSSC (97 to 100% identity), but HpaB Rs GMI1000 shares only 50.67% identity with HpaB Xcv 85-10. This raised the question of the functional conservation of HpaB class IB chaperone among Hrp2 plant pathogenic bacteria. We therefore investigated if HpaB proteins from R. solanacearum and Xcv, two phytopathogenic bacteria with different lifestyles, different modes in invasions, exhibiting different repertoires of T3Es and different host plants, were functionally interchangeable. Interestingly, trans-complementation for T3S using T3Es59, T3S regulators60, or T3Cs61 from other organisms was previously studied, mainly showing heterologous secretion or heterologous interactions. In this study, we functionally complement the R. solanacearum hpaB mutant to trigger an HR on tobacco plants using HpaB Xcv 85-10. We also show that secretion of RipP1 and RipP2 can be directed by HpaB Xcv 85-10 in R. solanacearum. This may explain the tobacco HR phenotype observed, consistent with a previous study showing that RipP1 secretion was required to trigger a full HR on tobacco plants at high concentrations14. We also observe that some common T3S features are conserved between the two phytopathogenic bacteria, as R. solanacearum RipP1 binds to HpaB Xcv 85-10 class IB chaperone, and Xcv is able to efficiently translocate a heterologous R. solanacearum T3E, in a HpaB Xcv 85-10 dependent manner. However, HpaB Rs GMI1000 and HpaB Xcv 85-10 are not fully interchangeable. Indeed, ectopic expression of hpaB Xcv 85-10 in R. solanacearum hpaB mutant leads to a partial complementation. hpaB Xcv 85-10 restores the HR phenotypes on tobacco, but not disease establishment on tomato. Pathogenicity of R. solanacearum on tomato is multifactorial, depending on numerous and functionally redundant T3Es62. This probably explains why the disease phenotype cannot be complemented whereas RipP1 alone is sufficient for elicitation of the HR14.

Another interesting result in our study is the fact that a R. solanacearum T3E can be translocated by Xcv 85-10 into pepper plant cells. This observation suggests that such class IB chaperones could play a role in the rapid adaptation of the pathogen by ensuring type III-dependent translocation of recently acquired T3Es (through horizontal gene transfer for example)12, 63. R. solanacearum is a remarkable plant pathogen as the RSSC comprises meta-repertoires of more than 100 T3E families, and 36 out of these T3E families share homologies with T3Es identified in the plant pathogenic bacteria Pseudomonas syringae, Xanthomonas and Acidovorax spp.62. Hence, the evolution of bacterial pathogenicity is clearly dynamic and loss or gain of T3Es can then lead to host range shifts. This abundance of virulence factors requires helper proteins to avoid uncontrolled delivery and a fine orchestration of T3E delivery presumably exists64. T3SSs are regulated by common mechanisms in different bacterial species6, and we now know that T3Cs, like HpaB class IB chaperones, are essential in this fine control and may significantly contribute to the bacterial plasticity to acquire or deliver new virulence factors.

Methods

Bacterial strains and media

The bacterial strains used in this work are listed in Supplementary Table S2. E. coli strains were grown at 37 °C in Luria–Bertani medium. R. solanacearum strains were grown in complete BG medium or in MP minimal medium as previously described65. The MP minimal medium was adjusted to pH 6.5 with KOH. When needed, antibiotics were added at the following final concentrations (mg/L): kanamycin (50), spectinomycin (40), gentamycin (10), tetracycline (10) for R. solanacearum and kanamycin (25), gentamycin (10), tetracycline (10), ampicillin (50), chloramphenicol (25) for E. coli.

R. solanacearum in vitro growth

The growth curves of the wild-type strain, the hpaB mutant and the hpaD mutant were measured in two culture media: complete BG medium and MP minimal medium supplemented with glutamate at a 20 mM final concentration. Overnight cultures were used to inoculate four replicates of 200 µl of fresh medium with an initial OD600nm at 0.1. Bacterial growth was performed in 96-well plates and monitored every 5 min using the FLUOstar Omega microplates reader (BMG Labtech, France). Experiments were repeated twice.

Phylogenetic analysis

The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Whelan and Goldman model66. The tree with the highest log likelihood (-653.1786) is shown. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to the branches. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using a Jones-Taylor-Thornton model67, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 125 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA668. The tree were manipulated and annotated using Interactive Tree Of Life tool (http://itol.embl.de/)69. The analysis involved 11 amino acid sequences belonging to the four phylotypes selected strains: GMI100070, Y4571 and FQY_472 from the phylotype I, CFBP295773 and K6074 from phylotype IIA, Molk273 and UY03175 from phylotype IIB, CMR1573 from phylotype III and Psi0773, R22976 and R2476 from phylotype IV. To generate protein matrix identity, sequences were aligned using MUSCLE77. Then proteins identities were calculated using SIAS tool (http://imed.med.ucm.es/Tools/sias.html).

Cloning

The plasmids used in this study and listed in Supplementary Table S2, were constructed by GatewayTM technology (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Plasmids in pENTR SD/D TOPO background were generated following manufacturer’s instructions using specific primers listed in Supplementary Table S3. Genes cloned in the pDONR207 plasmid were amplified in two steps. The first PCR was performed using the specific primers indicated in Supplementary Table S3. The second PCR was performed using 1 µL of the first PCR as matrix and oNP291-oNP292 universal primers. PCR products were cloned into pDONR207 using GatewayTM BP reaction following manufacturer’s conditions. Final plasmids for yeast two-hybrid, GST pull-down, and stable integration in a large non-coding chromosomic region downstream of the glmS gene in R. solanacearum 78 were generated using GatewayTM LR reaction.

Vectors for translocation assays using Xcv 85* strain and 85*ΔhpaB mutant were generated by Golden Gate cloning. First, RipP1 was amplified with compatible BsaI site and ligated into pGEM-T vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) to generate pFL92. Then, pFL92 was mixed with pBR356, BsaI restriction enzyme and T4 DNA ligase in a thermomixer using the following conditions: 37 °C for 1 hour, 50 °C for 10 min, 65 °C for 20 min to generate pFL98.

Yeast two-hybrid assays

Yeast two-hybrid experiments were performed as previously described32. Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain AH109 was cotransformed, using the LiAc methods79, with BD and AD fusions and plated on minimal synthetic-dropout (SD) medium (lacking leucine and tryptophan). Double transformants were tested for interaction by platting successive dilutions on minimal SD medium lacking leucine, tryptophan and histidine. Each interaction test was performed on four different colonies. Two to three biological repetitions were made for each interaction tested.

GST pull-down assays

GST fusion and 6His fusion proteins were synthesized in E. coli BL21(DE3). Bacterial cells from 50 mL cultures were resuspended in Phosphate Buffer Salt (PBS) and lysated with a French press. Cellular debris were eliminated by centrifugation. GST and GST fusion proteins were immobilized on a glutathione sepharose matrix, preliminarily washed with PBS, for 30 minutes. Unbound proteins were washed with PBS, and the glutathione sepharose matrix was incubated with 500 µl E. coli cell lysates containing the 6His fusion proteins for 2 hours. Unbound proteins were washed with PBS. Proteins were eluted with 10 mM reduced glutathione. Eluted proteins and protein lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using antibodies specific for the 6His epitope and GST (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). Experiments were repeated at least twice.

Pathogenicity assays

16 plants of Solanum lycopersicum cv. Marmande VR, from 3-4-week-old plants, were soaked with 500 mL of a bacterial suspension at 5.107 bacteria/mL. Disease development was monitored every day, and plants with at least 50% of wilting were considered as dead for the statistical survival analysis. To compare the disease development of two given strains, we used the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis with the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test80. A p-value smaller than 0.05 was considered significant, indicating that the Ho hypothesis of similarity of the survival experience of the tested strains can be rejected. Statistical analyses were done with Prism version 5.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Secretion assays

The pAM5 plasmid was introduced by electroporation into the wild-type strain, the hrcV mutant, the hpaB mutant and the hpaB mutant complemented versions: hpaB::hpaB Rs GMI1000 and hpaB::hpaB Xcv 85-10, to obtain a higher transcriptional activity of T3SS-regulated genes. Secretion assays and Western blot analysis were performed as previously described15. Antibodies used for Western blotting were RipG732, RipP181, RipP2 (courtesy of L. Deslandes, LIPM, INRA/CNRS, Castanet Tolosan, France), RipX82 and RipAA14. Goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase was used as secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.). For silver nitrate staining, samples were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE bisacrylamid gel. After migration, proteins were stained using Silver Stain Plus Kit (Bio-Rad, USA) following manufacturer conditions. Two biologically independent experiments were performed.

In vivo translocation assays and immunoblot analyses

Translocation assays were performed mostly as previously described83. Xcv strains (85* and 85*ΔhpaB mutant) were infiltrated into leaves of 4-week-old ECW-10R pepper plants (carrying Bs1 resistance gene), and ECW-30R pepper plants (carrying Bs3 resistance gene) at a concentration of 4.108 CFU/ml. Pepper plants were then incubated for 16 h light at 28 °C/8 h darkness at 22 °C, and 65% humidity. The appearance of HR was evaluated 2 days post infiltration. Leaves were destained in 70% ethanol. For verification of RipP1-AvrBs3Δ2 equal amounts of bacterial total cell extracts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using antibodies specific for AvrBs384. Horseradish peroxidase labeled anti-rabbit antibodies (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) was used as secondary antibodies. Experiments were performed twice.

References

Ailloud, F. et al. Comparative genomic analysis of Ralstonia solanacearum reveals candidate genes for host specificity. BMC Genomics 16, 270 (2015).

Hayward, A. C. Biology and epidemiology of bacterial wilt caused by Pseudomonas solanacearum. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 29, 65–87 (1991).

Peeters, N., Guidot, A., Vailleau, F. & Valls, M. Ralstonia solanacearum, a widespread bacterial plant pathogen in the post-genomic era. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14, 651–662 (2013).

Genin, S. Molecular traits controlling host range and adaptation to plants in Ralstonia solanacearum. New Phytol. 187, 920–928 (2010).

Genin, S. & Denny, T. P. Pathogenomics of the Ralstonia solanacearum species complex. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 50, 67–89 (2012).

Büttner, D. Protein export according to schedule: architecture, assembly, and regulation of type III secretion systems from plant- and animal-pathogenic bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 76, 262–310 (2012).

Tampakaki, A. P. et al. Playing the ‘Harp’: evolution of our understanding of hrp/hrc genes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 48, 347–370 (2010).

Mansfield, J. et al. Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13, 614–629 (2012).

Lindeberg, M., Cunnac, S. & Collmer, A. Pseudomonas syringae type III effector repertoires: last words in endless arguments. Trends Microbiol. 20, 199–208 (2012).

Roux, B. et al. Genomics and transcriptomics of Xanthomonas campestris species challenge the concept of core type III effectome. BMC Genomics 16, 975 (2015).

Piqué, N., Miñana-Galbis, D., Merino, S. & Tomás, J. M. Virulence Factors of Erwinia amylovora: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 12836–12854 (2015).

Peeters, N. et al. Repertoire, unified nomenclature and evolution of the type III effector gene set in the Ralstonia solanacearum species complex. BMC Genomics 14, 859 (2013).

Büttner, D. Behind the lines-actions of bacterial type III effector proteins in plant cells. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 40, 894–937 (2016).

Poueymiro, M. et al. Two type III secretion system effectors from Ralstonia solanacearum GMI1000 determine host-range specificity on tobacco. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact 22, 538–550 (2009).

Lonjon, F. et al. Comparative secretome analysis of Ralstonia solanacearum type 3 secretion-associated mutants reveals a fine control of effector delivery, essential for bacterial pathogenicity. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 15, 598–613 (2016).

Büttner, D. & He, S. Y. Type III protein secretion in plant pathogenic bacteria. Plant Physiol. 150, 1656–1664 (2009).

Lohou, D., Lonjon, F., Genin, S. & Vailleau, F. Type III chaperones & Co in bacterial plant pathogens: a set of specialized bodyguards mediating effector delivery. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 435 (2013).

Lorenz, C. & Büttner, D. Functional characterization of the type III secretion ATPase HrcN from the plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. J. Bacteriol. 191, 1414–1428 (2009).

Gauthier, A. & Finlay, B. B. Translocated intimin receptor and its chaperone interact with ATPase of the type III secretion apparatus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol 185, 6747–6755 (2003).

Thomas, J., Stafford, G. P. & Hughes, C. Docking of cytosolic chaperone-substrate complexes at the membrane ATPase during flagellar type III protein export. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 3945–3950 (2004).

Parsot, C., Hamiaux, C. & Page, A. L. The various and varying roles of specific chaperones in type III secretion systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6, 7–14 (2003).

Allaoui, A., Woestyn, S., Sluiters, C. & Cornelis, G. R. YscU, a Yersinia enterocolitica inner membrane protein involved in Yop secretion. J. Bacteriol. 176, 4534–4542 (1994).

Hausner, J. & Büttner, D. The YscU/FlhB homologue HrcU from Xanthomonas controls type III secretion and translocation of early and late substrates. Microbiol 160, 576–588 (2014).

Agrain, C. et al. Characterization of a type III secretion substrate specificity switch (T3S4) domain in YscP from Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 54–67 (2005).

Lorenz, C. et al. HpaC controls substrate specificity of the Xanthomonas type III secretion system. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000094 (2008).

Morello, J. E. & Collmer, A. Pseudomonas syringae HrpP Is a type III secretion substrate specificity switch domain protein that is translocated into plant cells but functions atypically for a substrate-switching protein. J. Bacteriol. 191, 3120–3131 (2009).

Büttner, D., Gürlebeck, D., Noël, L. D. & Bonas, U. HpaB from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria acts as an exit control protein in type III-dependent protein secretion. Mol. Microbiol 54, 755–768 (2004).

Büttner, D., Lorenz, C., Weber, E. & Bonas, U. Targeting of two effector protein classes to the type III secretion system by a HpaC- and HpaB-dependent protein complex from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Mol. Microbiol. 59, 513–527 (2006).

Büttner, D., Noël, L., Stuttmann, J. & Bonas, U. Characterization of the nonconserved hpaB-hrpF region in the hrp pathogenicity island from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 20, 1063–1074 (2007).

Scheibner, F., Schulz, S., Hausner, J., Marillonnet, S. & Büttner, D. Type III-dependent translocation of HrpB2 by a nonpathogenic hpaABC mutant of the plant-pathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 3331–3347 (2016).

Schulz, S. & Buttner, D. Functional characterization of the type III secretion substrate specificity switch protein HpaC from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Infect. Immun. 79, 2998–3011 (2011).

Lohou, D. et al. HpaP modulates type III effector secretion in Ralstonia solanacearum and harbours a substrate specificity switch domain essential for virulence. Mol. Plant Pathol. 6, 601–614 (2014).

Bonas, U. et al. How the bacterial plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria conquers the host. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1, 73–76 (2000).

Wengelnik, K., Rossier, O. & Bonas, U. Mutations in the regulatory gene hrpG of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria result in constitutive expression of all hrp genes. J. Bacteriol. 181, 6828–6831 (1999).

Szurek, B., Rossier, O., Hause, G. & Bonas, U. Type III-dependent translocation of the Xanthomonas AvrBs3 protein into the plant cell. Mol. Microbiol 46, 13–23 (2002).

Van den Ackerveken, G., Marois, E. & Bonas, U. Recognition of the bacterial avirulence protein AvrBs3 occurs inside the host plant cell. Cell 87, 1307–1316 (1996).

Ronald, P. C. & Staskawicz, B. J. The avirulence gene avrBs1 from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria encodes a 50-kD protein. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact 1, 191–198 (1988).

Izoré, T. et al. Structural characterization and membrane localization of ExsB from the type III secretion system (T3SS) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Mol. Biol. 413, 236–246 (2011).

Page, A.-L., Sansonetti, P. & Parsot, C. Spa15 of Shigella flexneri, a third type of chaperone in the type III secretion pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 1533–1542 (2002).

Bronstein, P. A., Miao, E. A. & Miller, S. I. InvB is a type III secretion chaperone specific for SspA. J. Bacteriol. 182, 6638–6644 (2000).

Lee, S. H. & Galán, J. E. InvB is a type III secretion-associated chaperone for the Salmonella enterica effector protein SopE. J. Bacteriol. 185, 7279–7284 (2003).

Creasey, E. A. et al. CesT is a bivalent enteropathogenic Escherichia coli chaperone required for translocation of both Tir and Map. Mol. Microbiol. 47, 209–221 (2003).

Elliott, S. J. et al. Identification of CesT, a chaperone for the type III secretion of Tir in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 33, 1176–1189 (1999).

Thomas, N. A. et al. CesT is a multi-effector chaperone and recruitment factor required for the efficient type III secretion of both LEE- and non-LEE-encoded effectors of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol 57, 1762–1779 (2005).

Kim, J.-G. et al. Characterization of the Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines Hrp pathogenicity island. J. Bacteriol. 185, 3155–3166 (2003).

Cho, H.-J. et al. Molecular analysis of the hrp gene cluster in Xanthomonas oryzae pathovar oryzae KACC10859. Microb. Pathog. 44, 473–483 (2008).

Furutani, A. et al. Identification of novel type III secretion effectors in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 22, 96–106 (2009).

Jiang, W. et al. Identification of six type III effector genes with the PIP box in Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris and five of them contribute individually to full pathogenicity. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 22, 1401–1411 (2009).

Alegria, M. C. et al. New protein-protein interactions identified for the regulatory and structural components and substrates of the type III Secretion system of the phytopathogen Xanthomonas axonopodis Pathovar citri. J. Bacteriol. 186, 6186–6197 (2004).

Hartmann, N. & Büttner, D. The inner membrane protein HrcV from Xanthomonas spp. is involved in substrate docking during type III secretion. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact 26, 1176–1189 (2013).

Lorenz, C. & Büttner, D. Secretion of early and late substrates of the type III secretion system from Xanthomonas is controlled by HpaC and the C-terminal domain of HrcU. Mol. Microbiol. 79, 447–467 (2011).

Schulze, S. et al. Analysis of new type III effectors from Xanthomonas uncovers XopB and XopS as suppressors of plant immunity. New Phytol. 195, 894–911 (2012).

Lorenz, C. et al. HpaA from Xanthomonas is a regulator of type III secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 69, 344–360 (2008).

Mukaihara, T., Tamura, N. & Iwabuchi, M. Genome-wide identification of a large repertoire of Ralstonia solanacearum type III effector proteins by a new functional screen. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact 23, 251–262 (2010).

Braun, P., Aubourg, S., Van Leene, J., De Jaeger, G. & Lurin, C. Plant protein interactomes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64, 161–187 (2013).

Miki, T., Shibagaki, Y., Danbara, H. & Okada, N. Functional characterization of SsaE, a novel chaperone protein of the type III secretion system encoded by Salmonella pathogenicity island 2. J. Bacteriol. 191, 6843–6854 (2009).

Neves, B. C. et al. CesD2 of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is a second chaperone for the type III secretion translocator protein EspD. Infect. Immun. 71, 2130–2141 (2003).

Zurawski, D. V. & Stein, M. A. The SPI2-encoded SseA chaperone has discrete domains required for SseB stabilization and export, and binds within the C-terminus of SseB and SseD. Microbiol. 150, 2055–2068 (2004).

Rossier, O., Wengelnik, K., Hahn, K. & Bonas, U. The Xanthomonas Hrp type III system secretes proteins from plant and mammalian bacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 9368–9373 (1999).

Botteaux, A., Sani, M., Kayath, C. A., Boekema, E. J. & Allaoui, A. Spa32 interaction with the inner-membrane Spa40 component of the type III secretion system of Shigella flexneri is required for the control of the needle length by a molecular tape measure mechanism. Mol. Microbiol. 70, 1515–1528 (2008).

Costa, S. C. P. et al. A new means to identify type 3 secreted effectors: functionally interchangeable class IB chaperones recognize a conserved sequence. mBio 3, e00243–11 (2012).

Deslandes, L. & Genin, S. Opening the Ralstonia solanacearum type III effector tool box: insights into host cell subversion mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 20, 110–117 (2014).

Schandry, N., de Lange, O., Prior, P. & Lahaye, T. TALE-like effectors are an ancestral feature of the Ralstonia solanacearum species complex and converge in DNA targeting specificity. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1225 (2016).

Büttner, D. & Bonas, U. Who comes first? How plant pathogenic bacteria orchestrate type III secretion. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9, 193–200 (2006).

Plener, L., Manfredi, P., Valls, M. & Genin, S. PrhG, a transcriptional regulator responding to growth conditions, is involved in the control of the type III secretion system regulon in Ralstonia solanacearum. J. Bacteriol. 192, 1011–1019 (2010).

Whelan, S. & Goldman, N. A general empirical model of protein evolution derived from multiple protein families using a maximum-likelihood approach. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18, 691–699 (2001).

Jones, D. T., Taylor, W. R. & Thornton, J. M. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 8, 275–282 (1992).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A. & Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729 (2013).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 242–245 (2016).

Salanoubat, M. et al. Genome sequence of the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. Nature 415, 497–502 (2002).

Li, Z. et al. Genome sequence of the tobacco bacterial wilt pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. J. Bacteriol. 193, 6088–6089 (2011).

Cao, Y. et al. Genome sequencing of Ralstonia solanacearum FQY_4, isolated from a bacterial wilt nursery used for breeding crop resistance. Genome Announc 1, e00125–13 (2013).

Remenant, B. et al. Genomes of three tomato pathogens within the Ralstonia solanacearum species complex reveal significant evolutionary divergence. BMC Genomics 11, 379 (2010).

Remenant, B. et al. Sequencing of K60, type strain of the major plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. J. Bacteriol. 194, 2742–2743 (2012).

Guarischi-Sousa, R. et al. Complete genome sequence of the potato pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum UY031. Stand. Genomic Sci. 11, 7 (2016).

Remenant, B. et al. Ralstonia syzygii, the Blood Disease Bacterium and some Asian R. solanacearum strains form a single genomic species despite divergent lifestyles. PloS One 6, e24356 (2011).

Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32, 1792–1797 (2004).

Monteiro, F., Solé, M., van Dijk, I. & Valls, M. A chromosomal insertion toolbox for promoter probing, mutant complementation, and pathogenicity studies in Ralstonia solanacearum. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact 25, 557–568 (2012).

Gietz, R. D. Yeast transformation by the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Methods Mol. Biol. 1205, 1–12 (2014).

Bland, J. M. & Altman, D. G. Survival probabilities (the Kaplan-Meier method). BMJ 317, 1572 (1998).

Lavie, M., Shillington, E., Eguiluz, C., Grimsley, N. & Boucher, C. PopP1, a new member of the YopJ/AvrRxv family of type III effector proteins, acts as a host-specificity factor and modulates aggressiveness of Ralstonia solanacearum. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact 15, 1058–1068 (2002).

Guéneron, M., Timmers, A. C., Boucher, C. & Arlat, M. Two novel proteins, PopB, which has functional nuclear localization signals, and PopC, which has a large leucine-rich repeat domain, are secreted through the hrp-secretion apparatus of Ralstonia solanacearum. Mol. Microbiol. 36, 261–277 (2000).

Drehkopf, S. et al. A TAL-based reporter assay for monitoring type III-dependent protein translocation in Xanthomonas. Methods Mol. Biol. 1531, 121–139 (2017).

Knoop, V., Staskawicz, B. & Bonas, U. Expression of the avirulence gene avrBs3 from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria is not under the control of hrp genes and is independent of plant factors. J. Bacteriol. 173, 7142–7150 (1991).

Acknowledgements

F.L. and D.L. were funded by a grant from the French Ministry of National Education and Research. F.L. was recipient of an ATUPS grant from University Paul Sabatier of Toulouse to perform experiments in Halle University. This work was supported by a French Agence Nationale de la Recherche grant (ANR-2010-JCJC-1710-01) to F.V. Our work is performed at the LIPM that is part of the Laboratoire d’Excellence (LABEX) entitled TULIP (ANR-10-LABX-41). Work in the group of D.B. is supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (CRC 648, project A8). We thank Fabrice Devoilles, Claudette Icher and Jean Luc Pariente for tobacco and tomato plant preparation. We thank Quitterie van de Kherkhove and Manon Sarthou for technical assistance. We thank Laurent Deslandes for the gift of the RipP2 antibody and GST-RipP1 and GST-RipP2 constructs, and Thomas Lahaye for the gift of RipTAL vector. We thank Jens Hausner for technical advices. We thank the other members of the SG lab for helpful discussions. This work benefited from interactions promoted by COST Action SUSTAIN (FA 1208).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.L., D.L., D.B., and F.V. designed research, F.L., D.L., D.B., B.G.R., C.P. and F.V. performed research, F.L., D.L., A.C.C. and S.G. contributed analytic tools, F.L., D.L., D.B. and F.V. analyzed data, F.L., D.B., S.G., and F.V. wrote or contributed to the writing of the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lonjon, F., Lohou, D., Cazalé, AC. et al. HpaB-Dependent Secretion of Type III Effectors in the Plant Pathogens Ralstonia solanacearum and Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria . Sci Rep 7, 4879 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04853-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04853-9

This article is cited by

-

Genome-scale Solanum spp.-Ralstonia solanacearum interactome reveals candidate determinants for host specificity and environmental adaptation

European Journal of Plant Pathology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.