Abstract

In the present study, we examined the ability of Enterobacter cloacae Z0206 to reduce toxic sodium selenite and mechanism of this process. E. cloacae Z0206 was found to completely reduce up to 10 mM selenite to elemental selenium (Se°) and form selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) under aerobic conditions. The selenite reducing effector of E. cloacae Z0206 cell was to be a membrane-localized enzyme. iTRAQ proteomic analysis revealed that selenite induced a significant increase in the expression of fumarate reductase. Furthermore, the addition of fumarate to the broth and knockout of fumarate reductase (frd) both significantly decreased the selenite reduction rate, which revealed a previously unrecognized role of E. cloacae Z0206 fumarate reductase in selenite reduction. In contrast, glutathione-mediated Painter-type reactions were not the main pathway of selenite reducing. In conclusion, E. cloacae Z0206 effectively reduced selenite to Se° using fumarate reductase and formed SeNPs; this capability may be employed to develop a bioreactor for treating Se pollution and for the biosynthesis of SeNPs in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Selenium (Se) is an important element for life and exhibits redox activity in the environment1. The Se cycle (see Figure S1, in Supplementary Information) is complex because the element can exist in a variety of oxidation states, ranging from −II to + VI2, 3. Se is released into the environment either from the weathering of Se-rich rocks2, 4 (e.g., black shales, carbonaceous, limestones, carbonaceous cherts, mudstones, and seleniferous coal) or from anthropogenic sources from industrial and agricultural activities5. Se can exist in the environment in multiple forms, including ionic selenate or selenite, solid-state Se(0), and selenocysteine/selenoproteins6. The toxicity rank of these forms is selenite > selenocysteine > selenate ≈ selenomethionine > elemental Se7,8,9,10. Apart from natural Se originating from weathering of seleniferous soils and rocks, anthropogenic activities, e.g. mining, metal refining and coal fire-based power production, lead to Se contamination in the environment11. Thus, remediation measures are required to treat Se contamination, because it has become an important public health concern12. At present, physicochemical methods, e.g. nanofiltration, reverse osmosis, ion exchange, ferrihydrite and zero valent iron, are usually used for Se removal from waste water. However, such physicochemical methods are commonly high-cost or inefficient for selenium removal13.

The lifetime of selenite in soils is closely associated with microbial activity11. Certain strains that are resistant to selenite and reduce selenite to the Se° or to methylated Se forms14,15,16,17,18, may potentially be used for the bioremediation of contaminated soils, sediments, industrial effluents, and agricultural drainage waters. The ABMet® Technology developed by GE Water & Process Technologies efficiently removes selenate and selenite from waste water via bacteria reduction, and the elemental Se could be separated from the biofilter tank through a backwash process11. It is worth noting that most bacterially assembled Se° particles are selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs), which are deposited inside a cell (cytoplasmic), within the periplasm or extracellularly12, 19,20,21. These particulate SeNPs display special physical characteristics, such as photoelectric, semiconducting and X-ray sensing properties11, 22. They also possess an adsorptive ability, antioxidant functions, and due to their high surface area-to-volume ratio, marked biological reactivity23,24,25,26. However, there is now growing concern about the environmental impact of nanoparticle synthesis based on physico-chemical methods that require high pressures and temperatures, are energy consuming, use toxic chemicals, and generate hazardous byproducts27. Consequently, applications using biological systems such as microbial cultures for the production of metal nanoparticles, including SeNPs, are becoming an increasingly realistic alternative27, 28.

Reduction of selenite to Se° has been shown to be mediated by thiols (Painter-type reactions) in the cytoplasm as part of a microbial detoxification strategy29. Selenite reacts with GSH and forms selenodiglutathione (GS-Se-SG), which is further reduced to glutathione selenopersulfide (GS-Se−) by NADPH-glutathione reductase. GS-Se− is an unstable intermediate and undergoes a hydrolysis reaction to form Se° and reduced GSH. In addition to Painter-type reactions, a number of terminal reductases for anaerobic respiration, two nitrite reductases, an inducible sulfite reductase and a fumarate reductase, have also been reported to be able to carry out selenite reduction in cells30,31,32,33.

Enterobacter cloacae SLD1a-1, a selenate-respiring facultative anaerobe, has been demonstrated to catalyze the reduction of both selenate and selenite to Se°12, 34, 35, but the selenite or selenate concentrations adopted in these studies were extremely low (less than 1.5 mM). The reduction of selenate was shown to be mediated by a membrane-bound molybdoenzyme36, 37, but the mechanism of selenite reduction in this strain has not been elucidated. Moreover, all of the selenite-reducing assays involving E. cloacae in these studies were performed in an anaerobic environment, and the selenite-reducing ability of E. cloacae has not previously been investigated under aerobic conditions. E. cloacae Z0206, a strain that we isolated from Reishi mushroom (Ganoderma lucidum) “meat”38, was found to possess excellent selenite resistance, tolerating more than 100 mM selenite. In the present investigation, we studied (i) the selenite-reducing ability of E. cloacae Z0206 under aerobic conditions, (ii) the characteristics and location of the produced SeNPs, and (iii) the mechanism of selenite reduction in the Z0206 strain.

Results and Discussion

Growth profile and selenite-reducing ability of E. cloacae Z0206 under different selenite concentrations

To determine the toxicity of selenite to the microorganism, the growth profile of E. cloacae Z0206 was studied under various concentrations of selenite (0, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 15 mM). According to the apparent changes in the spent broth shown in Fig. 1A, we found that the strain formed a reddish cell suspension, which indicated its ability to reduce the toxic, colorless, soluble selenite ions to the non-toxic, red, insoluble elemental form of Se (Se°). It is worth noting that the red color of the broth darkened, and viscosity increased with the increase of the selenite concentration. The results regarding the growth profile (Fig. 1B) showed that the addition of selenite strikingly inhibited the growth rate of E. cloacae Z0206, and the inhibitory effect strengthened with the increase of the selenite concentration during the log phase. However, the final cell density in the presence of selenite (0.5 mM–15 mM) was comparable to that of the control without selenite addition, as verified by the result of a bacteria counting assay performed at 96 h (Fig. 1C). Evaluation of the selenite-reducing ability of the bacterium (Fig. 1D) showed that selenite was rapidly reduced by this strain, with 10 mM selenite being completely reduced in 144 h. As shown in Fig. 1E, the rates of selenite reduction were modeled using the Michaelis-Menten kinetic equation (see section 1.1, in Supplementary Information). A nonlinear least-square analysis of the data yield a K m value of 4.37 mM and a V max of 59.32 μmol/h/g. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of the morphology of the bacterium and reduced selenite (Fig. 1F) revealed that as the selenite concentration increased, the rod-shaped cells tended to become shorter. Selenite at concentrations greater than or equal to 1 mM significantly stimulated the secretion of extracellular polymeric substances. SeNPs ranging from 100–300 nm were observed scattered around the cells and occurred as aggregates attached to the bacterial biomass in the presence of selenite, and the particle density grew with the increase of the selenite concentration. These results indicated that selenite merely reduced the growth rate of E. cloacae Z0206 rather than decreasing the final amount of bacteria. Additionally, the bacterium detoxified selenite by rapidly reducing it to Se° and formed SeNPs, highlighting the species as a promising exploitable option for setting up of low-cost biological treatment units for the bioremediation of Se-laden effluents.

Growth and selenite reduction of E. cloacae Z0206 in the presence of various concentrations of selenite. (A) Apparent changes in spent broth. (B) Growth profile under different selenite concentrations. Samples of 1 ml of the bacterial culture were collected at different time intervals of bacteria growth and then centrifuged at 4 °C and 10,000 × g for 10 min. Protein was extracted from the pellet using a total bacterial protein extraction assay kit. Bacterial growth was measured via the quantification of total cell protein. The protein concentration in bacteria cell extracts was determined. (C) Quantity of bacteria at the time point of 96 h. (D) Dynamic changes in selenite residue in the broth. (E) Kinetic study of selenite reduction by E. cloacae Z0206 under different selenite concentrations. Line graphs and bar graphs are presented as the mean ± SD, **P < 0.01 (n = 3). (F) SEM analysis of E. cloacae Z0206 under different selenite concentrations. The bacteria were cultured in the presence of various concentrations of selenite (0 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM and 15 mM). Samples were collected when the selenite was completely consumed according to the results in Fig. 1D.

Characterization and localization of SeNPs in Z0206 cultures

Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectrum (EDX) flat scanning of the area in Fig. 2A revealed a strong Se atom signal, accounting for 2.69% of the total component elements (Fig. 2B). EDX elemental mapping was used to detect the Se distribution. Four elemental maps of Se, carbon, oxygen and nitrogen were obtained and are shown in different colors based on the scanning area encompassing both the contents of E. cloacae Z0206 and the surrounding area (Fig. 2C). The map of elemental oxygen and nitrogen showed the cell shape and distribution of biomass. In contrast, element carbon was distributed both within and outside of cells because the cells were embedded by carbon-containing Epon plastic. However, the Se strong signals, shown in green, perfectly matched the profile of the extracellular nanoparticles, verifying that these particles were SeNPs. Moreover, Se, oxygen and nitrogen overlapped in the SeNPs distribution area, implying that these SeNPs may be coated with biomass. In addition, there was a weak Se signal inside the bacteria, suggesting that SeNPs may also exist inside the cells. However, Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis revealed the presence of electron-dense nanoparticles both within and outside of the cells (Fig. 2D), which was not found in cell cultures without selenite (see Figure S2, in Supplementary Information). The EDX spectra of these nanospheres clearly indicated the presence of Se, as specific absorption peaks at 1.37 and 11.22 keV were recorded (Fig. 2E). The lack of peaks corresponding to other metals indicated that Se occurred in its elemental state (Se°) rather than as a metal selenide. This was confirmed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis, which shows clearly the 3D spectral peak of Se° (Fig. 2F). These results suggested that E. cloacae Z0206 reduces Se(IV) to Se(0) and assembles it into nanoparticles.

Characterization and localization of E. cloacae Z0206 synthesized SeNPs. (A) SEM image of E. cloacae Z0206 and SeNPs. (B) EDX analysis of the contents of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and selenium in the area of (A). (C) Elemental mapping analysis of the distribution of selenium, carbon, oxygen and nitrogen in the area of (A). (D) TEM images of E. cloacae Z0206 and SeNPs. (E) EDX analysis of particle 1 and 2 in (D). (F) High-resolution Se 3D XPS of purified SeNPs synthesized by E. cloacae Z0206.

Selenite-reducing ability of different cellular fractions of E. cloacae Z0206 cells

Different mechanisms have been proposed for the reduction of selenite to Se° in microorganisms, including (i) Painter-type reactions29, (ii) the thioredoxin reductase system39, (iii) siderophore-mediated reduction40, (iv) sulfide-mediated reduction6 and (v) dissimilatory reduction30,31,32. Among these potential mechanisms, i, ii and v occur inside the cell, while the other reactions occur extracellularly. To help determine how selenite was reduced by E. cloacae Z0206, subcellular fractions, including cytoplasm, membrane proteins and the supernatant from liquid cultures, were isolated after 12 h of growth without selenite, and the selenite-reducing ability of each fraction was evaluated. As shown in Fig. 3, selenite was reduced to orange-colored Se by only the membrane-associated proteins after the addition of NADH, whereas little orange-colored Se occurred without NADH. However, boiling the membrane fraction samples resulted in a complete loss of reduction activity (data not shown). These results indicated that the reduction process mediated by membrane-associated proteins was an enzymatic reaction and was NADH dependent. Interestingly, the cytoplasmic fraction and supernatant failed to change the color to orange, suggesting that these two fractions possess no selenite-reducing ability.

Selenite-reducing ability of different fractions of E. cloacae Z0206. The selenite-reducing ability of the bacterium was estimated using the following reaction mixture: 100 µg protein, 10 mM selenite and 10 mM NADH in 200 µl Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 8 h. The reaction mixture with the total cell fraction and without selenite served as positive and negative controls, respectively.

iTRAQ analysis of E. cloacae Z0206 proteins in response to selenite

It is well established that α, β and γ proteobacteria possess high GSH levels in the cytoplasm, which drive Painter-type reduction to reduce selenite29. Although E. cloacae Z0206 is a γ proteobacterium, the above results indicated that it may reduce selenite through a membrane-bound enzyme rather than through a thiol-related reaction. To identify the probable mechanism involved, we undertook a large-scale proteomic analysis (iTRAQ) to examine the modification of protein expression in response to selenite (complete data on protein quantification are shown in Table S1, in Supplementary Information). The analysis focused on the proteins whose expression varied by more than a factor of 1.2. According to this criterion, 172 proteins were induced after selenite treatment, and 212 proteins were significantly repressed. All of the significantly differentially regulated proteins identified were subjected to gene ontology analysis. Among the 287 proteins involved in biological processes, 274 proteins and 175 proteins were dedicated to metabolic processes and cellular processes, respectively. For each of the three ontologies, the annotated data revealed that the proteins were mainly distributed among two or three of the general term categories. In the biological process category, the three most abundant categories included proteins that are involved in metabolic processes (244), cellular processes (230), and single-organism processes (198). In the molecular process category, the two main categories involved in catalytic activity (207) and binding (172). In the cellular component category, the three largest categories were cell (153), macromolecular complex (63), and membrane (61) (see Figure S3, in Supplementary Information).

Among the identified proteins, selenite induced a 2.42-fold increase in fumarate reductase abundance (Table 1). Li, et al.33 demonstrated that the reduction of selenite in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 is mediated by fumarate reductase, indicating that fumarate reductase may play a role in the selenite-reducing process in E. cloacae Z0206. However, the most expected antioxidant proteins, such as glutathione synthetase, glutathione reductase, glutathione-disulfide reductase, thioredoxin, thioredoxin reductase and thioredoxin-dependent thiol peroxidase, showed no significant change in response to selenite treatment (see Table S2, Support Information).

Analysis of the mRNA abundance of selected genes

To verify the results of the iTRAQ analysis, the mRNA abundance of the enzyme fumarate reductase (frd) and the antioxidative enzymes glutathione synthetase (gshA), glutathione reductase (gor), thioredoxin (trxA) and thioredoxin reductase (trxB) was assessed. As shown in Fig. 4, the mRNA expression of gshA, gor, trxA and trxB in cells after stimulation by selenite was not different from that before selenite treatment. However, selenite treatment promoted the mRNA expression of frd in a time-dependent manner. These data verified that E. cloacae Z0206 may reduce selenite to Se0 through fumarate reductase instead of via a GSH-mediated Painter-type reaction.

Effect of selenite on the transcription of fumarate reductase and enzymes involved in Painter-type reactions. An overnight culture of E. cloacae Z0206 was adjusted to OD600 = 1 and diluted into fresh broth (1%). When the culture reached the stationary phase, a 2 ml sample of the culture was removed (as a Se-free control). A 500 μL aliquot of the sodium selenite stock solution (1 M) was then added, and the culture was incubated for another 120 min. Samples were collected at 30 min, 60 min and 120 min after the addition of selenite. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (n = 3).

Effect of buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) on the selenite reduction rate in E. cloacae Z0206

To confirm that a GSH-mediated Painter-type reaction was not involved in the selenite-reducing process in E. cloacae Z0206, BSO, an inhibitor of glutathione synthetase, was used. As shown in Fig. 5A, BSO doses of 1.5 mM, 3.0 mM and 5.0 mM slightly decreased the growth rate during the exponential phase. In the stationary phase, the cell densities of all BSO-treated groups were slightly lower than that of the control group (all P < 0.05). Therefore, doses of 1.5 mM and 3.0 mM were chosen to study the effect of GSH on selenite reduction. As shown in Fig. 5B, the presence of 1.5 mM and 3.0 mM BSO did not result in any significant change in the selenite reduction rate. Z0206 cells were collected at 24 h, 48 h and 72 h to confirm the inhibitory effect of BSO on GSH synthesis (Fig. 5C). We found that the intracellular GSH concentration was decreased from 5.19 ± 0.24 to 2.16 ± 0.11 (1.5 mM BSO) and to 1.97 ± 0.15 (3.0 mM BSO) nmol/mg protein (both P < 0.001) at 24 h. This inhibition effect weakened and disappeared at 48 h and 72 h, respectively. However, the evidently lowered GSH concentration at 24 h did not lead to any significant change in the selenite reduction rate, indicating that a GSH-mediated Painter-type reaction was not the main pathway of selenite reduction in E. cloacae Z0206.

Effect of BSO on the growth and selenite reduction in E. cloacae Z0206. (A) Growth of E. cloacae Z0206 in the presence of 1.5 mM, 3.0 mM and 5.0 mM BSO. After that, Cells were incubated in the presence of 5 mM selenite while adding 0 mM, 1.5 mM or 3.0 mM BSO. Samples were collected at different time points to determine selenite residues, and cell samples were collected at 24 h, 48 h and 72 h to measure intracellular GSH concentrations. (B) Selenite reduction in the presence of BSO. The result was converted to a percentage of the initial selenite concentration. (C) Effect of BSO on intracellular GSH concentrations. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 (n = 3).

Effect of fumarate on the selenite reduction rate in E. cloacae Z0206

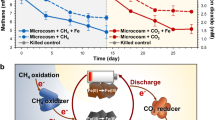

The effect of fumarate on the selenite-reducing ability of the bacterium was evaluated to investigate whether selenite reduction in E. cloacae Z0206 was mediated by fumarate reductase. First, the impact of fumarate on the growth of this strain was studied. As shown in Fig. 6A, different concentrations of fumarate did not affect the growth rate during the exponential phase, whereas a dose of 50 mM led to an evident increase in cell density during the stationary phase. Thus, a dose of 20 mM fumarate was selected to ensure that the cell density was similar to that of control cells without fumarate treatment. Based on the results shown in Fig. 6B, a dose of 20 mM fumarate significantly decreased the reduction rate. After 72 h, 41% and 72% remaining selenite was detected in the cultures without and with fumarate, respectively. These results indicated that competition existed between selenite and fumarate for fumarate reductase33, and fumarate reductase may present the main pathway of selenite reduction in E. cloacae Z0206.

Effect of fumarate reductase on selenite reduction in E. cloacae Z0206. (A) Effect of fumarate on the growth of E. cloacae Z0206. The bacteria were cultured with the addition of 10 mM, 20 mM, or 50 mM fumarate or without the presence of fumarate; the OD600 values were measured at the indicated time point after 3-fold dilution. (B) Effect of fumarate on the selenite reduction rate. The bacteria were cultured in the presence of 5 mM selenite with or without 20 mM fumarate treatment. Samples were collected at different time points and centrifuged at 4 °C at 10,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was used to determine the selenite residue. The selenite residue was converted to a percentage of the initial selenite concentration. (C) Effect of fumarate reductase mutation on the growth of E. cloacae Z0206. (D) Effect of fumarate reductase mutation on the selenite reduction rate in E. cloacae Z0206. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (n = 3), compared with the selenite residue of the control group or the wild-type group at the same time.

Effect of fumarate reductase knockdown on the selenite-reducing ability of E. cloacae Z0206

We constructed the fumarate reductase-mutated strain Δfrd to confirm that enzyme’s role in selenite reduction in E. cloacae Z0206. As shown in Fig. 6C, mutation of fumarate reductase did not significantly influence the growth of the cell. However, the mutant strain Δfrd exhibited a markedly repressed selenite-reducing capacity compared with the wild-type strain. After 72 h of reduction, 68.25% of the original selenite remained in cultures of the Δfrd strain, while only 42.58% of selenite could be detected in cultures of the wild-type strain (Fig. 6D). Therefore, E. cloacae Z0206 reduces selenite mainly through fumarate reductase.

In conclusion, many bacterial strains have been demonstrated to reduce selenite to Se0 and form SeNPs under anaerobic conditions, whereas bacteria grown in aerobic conditions possess the ability to rapidly generate more bacterial cells within a short time period and under less stringent culture conditions. In the present study, E. cloacae Z0206 was found to effectively reduce selenite to Se0 under aerobic conditions, and form monodispersed nanosized (approximately 100–300 nm in diameter) particles, which were observed both within and outside of the cells. Moreover, the selenite-reducing factor of E. cloacae Z0206 was demonstrated to be a membrane-localized fumarate reductase rather than a GSH-mediated Painter-type reaction. Biosynthesis of SeNPs under aerobic conditions presents advantages over the chemical process, in which SeNPs are produced under environmentally harmful conditions. Thus, E. cloacae Z0206 may be used to develop a bioreactor for the treatment of Se pollution and biosynthesis of SeNPs. Further studies may focus on the properties of biogenic SeNPs, compared with chemically synthesized SeNPs and the potential applications in the fields of nanotechnology and biotechnology.

Methods

Bacterial strain Z0206 and culture conditions

E. cloacae Z0206, a strain that we previously isolated38, was cultured in an optimized broth (sucrose 25, tryptone 5, yeast extract 5, K2HPO4·3H2O 2.62, KH2PO4 1, MgSO4 0.5 in g L−1) at 32 °C and 250 rpm.

Bacterial growth under selenite stress

The effect of selenite on the growth of E. cloacae Z0206 was determined in the presence of 0 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM and 15 mM sodium selenite. Sodium selenite was prepared as a 1 M stock solution and sterilized via filtration. Then, 500-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 ml broth was supplemented with increasing concentrations of selenite (0 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM and 15 mM), and an overnight-grown bacteria culture were adjusted to OD600 = 0.5 and inoculated (1% inoculum size) to the above mentioned broth containing various concentrations of selenite, followed incubation at 32 °C, 250 rpm for 96 h.

Determination of selenite concentration

The culture was collected and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected to detect residual selenite through the 2,3-diaminonaphthalene fluorimetric method41. Please see section 1.2 in Supplementary Information for introduction of the method to detect selenite.

SEM and EDX analysis

Cultures of Z0206 in grown the presence of different concentrations of selenite (0 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM and 15 mM) were collected. These samples were centrifuged at 4 °C, 12,000 × g for 15 min, and then the pellets were washed (0.1 M PBS), fixed, dried and sputter-coated, followed by viewing under SEM. Elemental composition maps of selected areas were analyzed with the EDX system.

TEM and EDX analysis

Cultures of Z0206 grown in the presence of various concentrations of selenite (0 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM and 15 mM) were collected. These samples were centrifuged at 4 °C, 12,000 × g for 15 min, and then the pellets were washed (0.1 M PBS), fixed, dried and embedded. Ultrathin sections of 100 nm were cut and stained, followed by viewing under TEM. The elemental composition of selected particles was analyzed using the EDX system.

Se particle valence analysis

E. cloacae Z0206 was cultured in the presence of 5 mM selenite at 32 °C at 250 rpm for 72 h. Selenium particles were separated from the culture according to the protocol developed by Dobias, et al.42. with some modification. Briefly, the culture was decanted, followed by simple centrifugation at 4 °C at 8,000 ×g for 10 min to separate the suspended biomass. The collected Se particles present in the supernatant from the previous centrifugation step were concentrated via centrifugation at 4 °C at 20,000 ×g for 15 min. The pellet was then lyophilized and analyzed using XPS.

Separation of cellular fractions and determination of selenite-reducing activity

An E. cloacae Z0206 culture grown to the exponential phase without selenite was collected and centrifuged at 4 °C at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was then collected and filtered using a 0.2-µm filter. Next, the pellet was washed with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) twice and re-suspended in the same buffer for sonication, followed by centrifugation at 4 °C at 6,000 × g for 10 min to separate unbroken cells. Then, the supernatant was centrifuged at 4 °C at 25,000 × g for 40 min to separate the cytoplasm (supernatant) and membrane (pellet) fractions. The protein concentration was measured with a BCA assay kit.

RT-PCR analysis

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Protect Bacteria Mini Kit. Total RNA was subjected to a reverse transcription reaction using a Quanti Tect Reverse Transcription Kit. Quantitative PCR was performed with a StepOne Plus™ Real Time PCR System using a FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (ROX).

Determination of intracellular GSH concentrations

Cells, collected from the experiment on the “Effect of BSO on selenite reduction in E. cloacae Z0206” at the time points of 24 h, 48 h and 72 h, were concentrated via centrifugation at 10,000 × g, 4 °C for 10 min and resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), after which the cells were disrupted using sonication. The disrupted cells were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatants were collected to detect the concentration of GSH using a Total Glutathione Assay Kit.

Construction of the Δfrd mutant

The Δfrd mutant was constructed as reported elsewhere43. Briefly, an frd gene fusion fragment was amplified and ligated via PCR, then ligated with pLP12 and subsequently transformed into Escherichia coli β2163. The resulting plasmids were introduced into E. cloacae Z0206 through conjugation with E. coli β2163. After two rounds of selection, the mutant carrying the frd gene deleted was validated through PCR using primers corresponding to sequences upstream and downstream of the deletion (see Figure S4, in Supplementary Information) and subsequent sequencing.

Statistics

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by an LSD multiple comparison test was used to determine the statistical significance for multiple comparisons, and Student’s t-test was used for pairwise comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were carried out with SPSS 22 software. All data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request.

References

Sharma, V. K. et al. Biogeochemistry of Selenium. A Review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 13, 49–58, doi:10.1007/s10311-014-0487-x (2015).

Winkel, L. H. E. et al. Environmental Selenium Research: From Microscopic Processes to Global Understanding. Environmental Science & Technology 46, 571–579, doi:10.1021/es203434d (2012).

Nancharaiah, Y. V. & Lens, P. N. L. Selenium Biomineralization for Biotechnological Applications. Trends in Biotechnology 33, 323–330, doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.03.004 (2015).

Sun, G.-X. et al. Distribution of Soil Selenium in China Is Potentially Controlled by Deposition and Volatilization? Scientific Reports 6, doi:10.1038/srep20953 (2016).

Fernández-Martínez, A. & Charlet, L. Selenium Environmental Cycling and Bioavailability: A Structural Chemist Point of View. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology 8, 81–110, doi:10.1007/s11157-009-9145-3 (2009).

Zannoni, D., Borsetti, F., Harrison, J. J. & Turner, R. J. in Advances in Microbial Physiology, Vol 53 Vol. 53 Advances in Microbial Physiology (ed RK Poole) 1–71 (2008).

Jayaweera, G. R. & Biggar, J. W. Role of Redox Potential in Chemical Transformations of Selenium in Soils. Soil Science Society of America Journal 60, 1056–1063 (1996).

Stolz, J. F. & Oremland, R. S. Bacterial Respiration of Arsenic and Selenium. Fems Microbiology Reviews 23, 615–627, doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.1999.tb00416.x (1999).

Wang, H., Zhang, J. & Yu, H. Elemental Selenium at Nano Size Possesses Lower Toxicity without Compromising the Fundamental Effect on Selenoenzymes: Comparison with Selenomethionine in Mice. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 42, 1524–1533, doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.013 (2007).

Siwek, B. et al. Effect of Selenium-Compounds on Murine B16 Melanoma-Cells and Pigmented Cloned PB16 Cells. Archives of Toxicology 68, 246–254, doi:10.1007/s002040050064 (1994).

Nancharaiah, Y. V. & Lens, P. N. L. Ecology and Biotechnology of Selenium-Respiring Bacteria. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 79, 61–80, doi:10.1128/mmbr.00037-14 (2015).

Lampis, S. et al. Delayed Formation of Zero-Valent Selenium Nanoparticles by Bacillus mycoides SeITE01 as a Consequence of Selenite Reduction under Aerobic Conditions. Microbial Cell Factories 13, doi:10.1186/1475-2859-13-35 (2014).

Lenz, M. & Lens, P. N. L. The Essential Toxin: The Changing Perception of Selenium in Environmental Sciences. Science of the Total Environment 407, 3620–3633, doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.07.056 (2009).

Stolz, J. E., Basu, P., Santini, J. M. & Oremland, R. S. in Annual Review of Microbiology Vol. 60 Annual Review of Microbiology 107–130 (2006).

Favre-Bonte, S. et al. Freshwater Selenium-Methylating Bacterial Thiopurine Methyltransferases: Diversity and Molecular Phylogeny. Environmental Microbiology 7, 153–164, doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00670.x (2005).

Ranjard, L., Nazaret, S. & Cournoyer, B. Freshwater Bacteria Can Methylate Selenium through the Thiopurine Methyltransferase Pathway. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 69, 3784–3790, doi:10.1128/aem.69.7.3784-3790.2003 (2003).

Ranjard, L. et al. Characterization of a Novel Selenium Methyltransferase from Freshwater Bacteria Showing Strong Similarities with the Calicheamicin Methyltransferase. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Gene Structure and Expression 1679, 80–85, doi:10.1016/j.bbaexp.2004.05.001 (2004).

Avendano, R. et al. Production of Selenium Nanoparticles in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Scientific Reports 6, doi:10.1038/srep37155 (2016).

Debieux, C. M. et al. A Bacterial Process for Selenium Nanosphere Assembly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, 13480–13485, doi:10.1073/pnas.1105959108 (2011).

Zheng, S. X. et al. Selenite Reduction by the Obligate Aerobic Bacterium Comamonas testosteroni S44 Isolated from a Metal-Contaminated Soil. Bmc Microbiology 14, doi:10.1186/s12866-014-0204-8 (2014).

Bao, P. et al. Characterization and Potential Applications of a Selenium Nanoparticle Producing and Nitrate Reducing Bacterium Bacillus oryziterrae Sp Nov. Scientific Reports 6, doi:10.1038/srep34054 (2016).

Chaudhary, S., Umar, A. & Mehta, S. K. Selenium Nanomaterials: An Overview of Recent Developments in Synthesis, Properties and Potential Applications. Progress in Materials Science 83, 270–329, doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2016.07.001 (2016).

Wang, H. L., Zhang, J. S. & Yu, H. Q. Elemental Selenium at Nano Size Possesses Lower Toxicity without Compromising the Fundamental Effect on Selenoenzymes: Comparison with Selenomethionine in Mice. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 42, 1524–1533, doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.013 (2007).

Li, Y. et al. The Reversal of Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity by Selenium Nanoparticles Functionalized with 11-Mercapto-1-Undecanol by Inhibition of Ros-Mediated Apoptosis. Biomaterials 32, 9068–9076, doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.001 (2011).

Rezvanfar, M. A. et al. Protection of Cisplatin-Induced Spermatotoxicity, DNA Damage and Chromatin Abnormality by Selenium Nano-Particles. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 266, 356–365, doi:10.1016/j.taap.2012.11.025 (2013).

Liao, W. et al. Biofunctionalization of Selenium Nanoparticle with Dictyophora Indusiata Polysaccharide and Its Antiproliferative Activity through Death-Receptor and Mitochondria-Mediated Apoptotic Pathways. Scientific Report 5, doi:10.1038/srep18629 (2015).

Oremland, R. S. et al. Structural and Spectral Features of Selenium Nanospheres Produced by Se-Respiring Bacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 70, 52–60, doi:10.1128/aem.70.1.52-60.2004 (2004).

Shirsat, S., Kadam, A., Naushad, M. & Mane, R. S. Selenium Nanostructures: Microbial Synthesis and Applications. Rsc Advances 5, 92799–92811, doi:10.1039/c5ra17921a (2015).

Kessi, J. & Hanselmann, K. W. Similarities between the Abiotic Reduction of Selenite with Glutathione and the Dissimilatory Reaction Mediated by Rhodospirillum rubrum and Escherichia coli. Journal of Biological Chemistry 279, 50662–50669, doi:10.1074/jbc.M405887200 (2004).

Basaglia, M. et al. Selenite-Reducing Capacity of the Copper-Containing Nitrite Reductase of Rhizobium sullae. Fems Microbiology Letters 269, 124–130, doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00617.x (2007).

Demolldecker, H. & Macy, J. M. The Periplasmic Nitrite Reductase of Thauera-selenatis May Catalyze the Reduction of Selenite to Elemental Selenium. Archives of Microbiology 160, 241–247 (1993).

Harrison, G., Curle, C. & Laishley, E. J. Purification and Characterization of an Inducible Dissimilatory Type Sulfite Reductase from Clostridium-pasteurianum. Archives of Microbiology 138, 72–78, doi:10.1007/bf00425411 (1984).

Li, D. B. et al. Selenite Reduction by Shewanella Oneidensis Mr-1 Is Mediated by Fumarate Reductase in Periplasm. Scientific Reports 4, doi:10.1038/srep03735 (2014).

Losi, M. E. & Frankenberger, W. T. Reduction of Selenium Oxyanions by Enterobacter cloacae SLD1a-1: Isolation and Growth of the Bacterium and Its Expulsion of Selenium Particles. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 63, 3079–3084 (1997).

Dungan, R. S. & Frankenberger, W. T. Reduction of Selenite to Elemental Selenium by Enterobacter cloacae SLD1a-1. Journal of Environmental Quality 27, 1301–1306 (1998).

Ridley, H., Watts, C. A., Richardson, D. J. & Butler, C. S. Resolution of Distinct Membrane-Bound Enzymes from Enterobacter cloacae SLD1a-1 That Are Responsible for Selective Reduction of Nitrate and Selenate Oxyanions. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 72, 5173–5180, doi:10.1128/aem.00568-06 (2006).

Butler, C. S., Debieux, C. M., Dridge, E. J., Splatt, P. & Wright, M. Biomineralization of Selenium by the Selenate-Respiring Bacterium Thauera selenatis. Biochemical Society Transactions 40, 1239–1243, doi:10.1042/bst20120087 (2012).

Xu, C. L., Wang, Y. Z., Jin, M. L. & Yang, X. Q. Preparation, Characterization and Immunomodulatory Activity of Selenium-Enriched Exopolysaccharide Produced by Bacterium Enterobacter cloacae Z0206. Bioresource Technology 100, 2095–2097, doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2008.10.037 (2009).

Yamada, A., Miyashita, M., Inoue, K. & Matsunaga, T. Extracellular Reduction of Selenite by a Novel Marine Photosynthetic Bacterium. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 48, 367–372 (1997).

Zawadzka, A. M., Crawford, R. L. & Paszczynski, A. J. Pyridine-2,6-Bis(Thiocarboxylic Acid) Produced by Pseudomonas stutzeri KC Reduces and Precipitates Selenium and Tellurium Oxyanions. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 72, 3119–3129, doi:10.1128/aem.72.5.3119-3129.2006 (2006).

Hall, R. J. & Gupta, P. L. Determination of Very Small Amounts of Selenium in Plant Samples. Analyst 94, 292–&, doi:10.1039/an9699400292 (1969).

Dobias, J., Suvorova, E. I. & Bernier-Latmani, R. Role of Proteins in Controlling Selenium Nanoparticle Size. Nanotechnology 22, doi:10.1088/0957-4484/22/19/195605 (2011).

Luo, P., He, X., Liu, Q. & Hu, C. Developing Universal Genetic Tools for Rapid and Efficient Deletion Mutation in Vibrio Species Based on Suicide T-Vectors Carrying a Novel Counterselectable Marker, Vmi480. Plos One 10, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144465 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Modern Agroindustry Technology Research System (No. CARS-36). We thank the staff at the Electronic Microscopy Center, Agricultural, Biological and Environmental Test Center and Condensed Matter Physics Research Platform in Zhejiang University for their assistance with the TEM, SEM and EDX assay, flow cytometry and FT-IR assays, and XPS analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Deguang Song, Fengqin Wang and Yizhen Wang designed the research, Deguang Song, Xiaoxiao Li, Yuanzhi Cheng, Xiao Xiao, Fengqin Wang and Zeqing Lu performed the experiments, Deguang Song, Fengqin Wang and Yizhen Wang performed data analysis, Deguang Song wrote the article. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, D., Li, X., Cheng, Y. et al. Aerobic biogenesis of selenium nanoparticles by Enterobacter cloacae Z0206 as a consequence of fumarate reductase mediated selenite reduction. Sci Rep 7, 3239 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03558-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03558-3

This article is cited by

-

Whole genome sequencing and analysis of selenite-reducing bacteria Bacillus paralicheniformis SR14 in response to different sugar supplements

AMB Express (2023)

-

Preparation, characteristics and cytotoxicity of green synthesized selenium nanoparticles using Paenibacillus motobuensis LY5201 isolated from the local specialty food of longevity area

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Selenite bioreduction with concomitant green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles by a selenite resistant EPS and siderophore producing terrestrial bacterium

BioMetals (2023)

-

Nanomicrobiology: Emerging Trends in Microbial Synthesis of Nanomaterials and Their Applications

Journal of Cluster Science (2023)

-

A State-of-the-Art Systemic Review on Selenium Nanoparticles: Mechanisms and Factors Influencing Biogenesis and Its Potential Applications

Biological Trace Element Research (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.