Abstract

The oxidation mechanism of sulfides is the key issue during the sulphide–metallurgy process. In this study, the phase transformation and element migration were clearly demonstrated by in–situ laboratory–based X–ray diffraction (XRD) and energy–dispersive X–ray spectroscopy (EDS), respectively. The reaction sequence and a four–step oxidation mechanism were proposed and identified. The elemental distribution demonstrated that at a low temperature, the Fe atoms diffused outward and the Ni/Cu atoms migrated toward the inner core, whereas the opposite diffusion processes were observed at a higher temperature. Importantly, the unique visual presentation of the oxidation behaviour provided by the combination of in–situ XRD and EDS might be useful for optimising the process parameters to improve the Ni/Cu extraction efficiency during Ni–Cu sulphide metallurgy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the first super–large magmatic Ni–Cu–platinum–group elements (PGE) deposit (Sudbury, Canada) was discovered in 1883, several super–large Ni–Cu–PGE deposits rich in sulphides have been mined (e.g., Jinchuan Ni–Cu–Co–PGE deposit (China), Noril’sk Ni–Cu–PGE and Pechenga Ni–Cu–PGE deposits (Russia), Voisey’s Bay Ni–Cu–Co deposit (Canada))1. Magmatic–sulphide deposits host ~40% of the global Ni resources and supply ~60% of the Ni in the world market. With the unceasing mining and consumption of the rich ore resources, the extensive exploitation and utilization of low–grade nickel sulphide ores are becoming important problems for the sustainability of nickel production.

As a traditional pyrometallurgy method, the flash smelting–converter–grinding–floatation–anode electrolysis process requires a high nickel concentrate and is tedious and complicated. From the 1960s to the 1990s, an oxidation–sulphation roasting process followed by leaching was proposed and investigated to treat low–grade Ni–Cu sulphide ores2,3,4,5,6. The oxidation behaviour of sulphide ores, which is of principal and vital importance in the sulphide–extraction metallurgy process, is complex and highly dependent on the sulphides phases in the minerals. Pentlandite (expressed as Pn) and chalcopyrite (expressed as Ccp), which are the common minerals used in pyrometallurgical nickel and copper production, respectively, have been theoretically and experimentally investigated during the oxidative–roasting process by many researchers for decades7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. A detailed review of the oxidation mechanisms of Pn and Ccp is presented in Fig. 1.

Early on, the various oxidative reactions of natural Pn were deduced and summarised via thermogravimetric (TG)/mass spectroscopy (MS) analysis, differential thermal analysis (DTA), and X–ray diffraction (XRD) analysis by Dunn et al.8. Recently, researchers studied the isothermal oxidation behaviour of synthetic Pn in depth and proposed a novel stepwise phase–transformation mechanism13, 14. As shown in Fig. 1, pure Pn is first decomposed into intermediate sulphide (e.g., (Fe,Ni)xSy, FeyNi1–yS, Ni3S2, NiS) and finally oxidised into Fe2O3, NiO, and NixFe2+xO4. For the past few years, researchers have tended to investigate the oxidation behaviour of Pn taken nickel concentrate as a raw material15, 17,18,19.

As the most exploited mineral for the extraction metallurgy of copper, Ccp has been extensively studied theoretically and experimentally7, 9,10,11,12, 16, 20,21,22,23. Prasad et al.17 suggested that it was extremely important and necessary for copper extraction to concentrate on the oxidative–roasting procedure of Ccp. Various reactions occurring in the oxidation of Ccp were summarised in early studies and are briefly presented in Fig. 1 7, 13,14,15, 17, 18, 21, 22, 24, 25. As shown in this figure, the first stage is the oxidation of Ccp into Cu2S (or Cu5FeS4) and FeS. This is followed by the formation of metal sulphates and finally the decomposition of the sulphates of iron and copper into oxides (e.g., CuO.CuSO4, CuO, Fe2O3, Cu x Fe3−x O4−y ). A. Baba et al. 23 conducted a detailed review of the role of Ccp in the pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical processes of copper, and suggested that low–grade complex sulphide ores have attracted attention because of the recent decline in deposits of high–grade ores.

Another interesting and important problem that occurs during the oxidative roasting of polymetallic sulphides is the elemental distribution of the ore grains. Many researchers13,14,15, 17, 21, 22, 26 have investigated the preferential oxidation of Fe and S during the roasting process using energy–dispersive X–ray spectroscopy (EDS), reporting that the Ni or Cu tends to diffuse into the centre while Fe migrates outward to the oxide rim layer.

Given the aforementioned findings, the oxidation mechanism of the sulphide mineral, which is a long– and well–studied problem, has been investigated in detail using traditional analysis and characterization methods, such as TG, DTA, MS, XRD and EDS. Because of the complexity of the Ni–Cu sulphide ore and the weakness of traditional characterization methods, some of the oxidation mechanisms proposed by early researchers should be further examined. However, thorough studies on the oxidative mechanism of polymetallic sulphide minerals have rarely been reported. The in–situ XRD method, which has recently been used to investigate the mechanism of the metallurgical process, is growing in popularity27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. In this study, the oxidation behaviour of a Ni–Cu sulphide ore was investigated in detail during the roasting process using in–situ laboratory–based XRD and EDS in tandem.

Results and Discussion

Phase evolution during oxidation process

To investigate the thermodynamics of the Ni–Cu sulphide mineral system, a phase–stability diagram for the Ni4.5Fe4.5S8–CuFeS2–SO2–O2 system at 450 to 900 °C in air (p(O2) = 0.21 atm) was developed using the Factsage software package35. As shown in Fig. 2, at the lower temperatures, the main stable phases were metal sulphates (Fe2(SO4)3, CuSO4, and NiSO4) together with Fe2O3. As the temperature increases, the predominance areas shift toward the formation of oxides.

The TG and differential TG (DTG) curves for different heating rates in Fig. S2a and b are similar in shape, and the peaks shift to a higher temperature as the heating rate increases. The TG cures in Fig. S2a indicate that there was a gradual mass increase in the range of 400 to 550 °C and that the mass tended to decrease around 550 °C. Correspondingly, Fig. S2b shows that the formation of metal sulphates might be responsible for the two peaks (peak 1 and 2) that occurred during the mass–increasing process, whereas the other four peaks (peaks 3, 4, 5, and 6) might result from the direct oxidation of sulphides into oxides and the decomposition of the formed sulphates. Fig. S2c shows that the amount of sulphates increased at different rates as the temperature increased; reached maximums of approximately 550, 600, and 700 °C for Fe2(SO4)3, CuSO4, and NiSO4, respectively; and finally decomposed at higher temperatures.

In–situ laboratory–based XRD analysis was performed to explore the phase transformation of the Ni–Cu sulphide ore during the oxidative–roasting process. Fig. 3 plots the accumulated in–situ XRD data collected during the roasting process. And weight fractions of the phases present at each temperature are shown in Fig. S3. At “low” temperatures (here defined as <300 °C), the peak intensity of the sulphides (Pn, Ccp, and pyrrhotite (Fe7S8)) slowly decreased, but as the temperature increased, the peak intensity of pyrite (FeS2) increased, which indicates that Pn, Ccp, and pyrrhotite slowly decomposed36. When the temperature reached 350 °C or higher, the sulphides oxidised rapidly and disappeared round 400, 450 and 500 °C for Pn, Pyrrhotite and Ccp respectively, and the initial oxidative products were metal sulphates (Fe2(SO4)3, CuSO4) and NiS. In the range of 350 to 650 °C, the peak intensity of Fe2O3 gradually increased, reaching its maximum at 650 °C. As the temperature increased from 500 to 700 °C, the NiS phase gradually decreased and was eventually eliminated; however, the spinel and NiO phases exhibited a different behaviour. As the temperature increased from 650 to 900 °C, the spinel and NiO phases increased, while the Fe2O3 phase tended to decrease. As shown in Figs 3 and S3, the generation and transformation processes differed significantly among the sulphate phases. For example, the Fe2(SO4)3 phase appeared at 400 °C and disappeared at ~650 °C (Fig. S3c); however, the appearance and increase of the NiSO4 phase occurred at 550–700 °C, and the NiSO4 decomposed and disappeared at 850 °C (Fig. S3a). The CuSO4 phase was generated together with the Fe2(SO4)3 phase at 400 °C and then gradually disappeared with the appearance and increase of the CuO.CuSO4 phase at 700–800 °C. Finally, the CuO.CuSO4 phase disappeared at 850 °C (Fig. S3b).

For a better understanding of the oxidation behaviour of the Ni–Cu sulphide ore, a series of characteristic–peak ranges were measured using the in–situ laboratory–based XRD with the position–sensitive detector (PSD) fixed model. According to the patterns shown in Fig. 4, the oxidative processes of the Ni–Cu sulphide ore are discussed in detail as follows:

Initial oxidative stage: At the beginning, the sulphide–mineral sample hardly changed as the temperature increased. However, there may have been subtle variations in the peak intensities for Pn and Ccp, as shown in Fig. 4b and c, which indicated the slow decomposition of the sulphides8. Then, both the Pn and Ccp disappeared rapidly at ~425 °C, as shown in Fig. 4b,c and e. The Mag was gradually oxidised into Fe2O3 above 425 °C, as shown in Fig. 4d,e and f.

Sulphation stage: As shown in Figs 4a,c and S3, the sulphates (Fe2(SO4)3 and CuSO4) were formed almost instantaneously around 425 °C and increased gradually with the increase of the oxidation temperature. Figure 4a shows that the Fe2(SO4)3 phases gradually transformed into iron oxide (Fe2O3) and iron oxide sulphate (Fe2O3.5Fe2(SO4)3) in the temperature range of 500 to 700 °C. Then, the iron oxide sulphate (Fe2O3.5Fe2(SO4)3) decomposed into Fe2O3 and disappeared at ~750 °C.

As shown in Fig. 4a, CuSO4 was rapidly generated around 425 °C and remained stable below ~600 °C. CuO.CuSO4, which was detected in the range of 650 to 750 °C, was the decomposition product of CuSO4 (Figure S3b). However, as shown in Fig. 4b and c, the Pn was first transformed into the NiS phase in the temperature range of 425 to 500 °C, and then the NiS phase gradually increased with the temperature, disappearing at ~650 °C. As shown in Fig. 4a, NiSO4 was formed in a higher temperature range—700 to 800 °C—which is consistent with the range shown in Fig. S3a (600 to 800 °C).

Spinel–formation stage: As demonstrated in Fig. 4c, the iron oxide (Fe2O3) increased rapidly around 500 °C and reached its maximum value when the temperature increased to ~750 °C. In addition, as shown in Fig. 4a and c, the remarkable changes of the Fe2O3 diffraction peak profile occurred during the heating and cooling processes, which might be the results of the growth of Fe2O3 crystal. As shown in Fig. S4, the [104] crystal size of Fe2O3 firstly increased at the heating stage, remained constant at the temperature range from 600 °C to 700 °C, and increased at temperature up to 800 °C, then remained unchanged until the cooling stage. The spinel phase was initially generated around 750 °C, as shown in Fig. 4b,d,e and f. Then, the spinel phase gradually increased with the temperature. In contrast, the Fe2O3 was reduced as the temperature increased. As shown in Fig. 4e and f, the diffraction patterns of the Ni–spinel and Cu–spinel phases were separated and revealed clearly, whereas the diffraction peaks of the NiO and Ni–spinel phases exhibited serious overlap. The Cu–spinel was formed with priority, and then the Ni–spinel and NiO peaks were detected.

Cooling stage: The phase components of the sample remained constant in the cooling stage, as shown in Fig. 4. The diffraction peaks significantly shifted to a large angle because of the lattice contraction during the cooling process. Conversely, the lattice expansion during the roasting caused the peaks to shift to a small angle.

Elemental migration and distribution

The elemental distribution of the cross–section of the particles was studied by EDS, as discussed in this section. The SEM and EDS analysis of Pn and Ccp grains at different temperatures are shown in Figs S5 and S6, respectively. The element migration in the Pn and Ccp grains was similar in the initial oxidative stage (~450 °C). As shown in Figs 5b and 6b, the Fe atoms in Pn and Ccp migrated to the surface and preferentially oxidised into a dense, thin oxide layer (4–5 µm), whereas the Ni and Cu tended to migrate to the centre of the grains in the earlier oxidation stage. Fig. 5c shows that there were three layers of Pn grains at this stage. According to the in–situ XRD (Figs 3 and 4) and EDS spot (Fig. S5a) analyses, these three layers were the Fe2(SO4)3 outer layer, the intermediate thin band of the NiS phase, and the inner core of Pn or (Ni,Fe)9S8–x (Pn’). However, for the Ccp particles (Fig. 6c and Fig. S6a), the outer side was an Fe2O3 dense layer, while the inner side was Ccp or CuFeS2–y (Ccp’).

As the temperature increased to 550 °C (Figs 5e, 6e and Figs S5b, S6b), the oxidised gas product (SO2) diffusing outward collided with the O2 undergoing inward diffusion at the rim of the Fe2O3 layer. As shown in Figs 5f and 6f, the Fe2(SO4)3 outer rims were then formed at both the Pn and Ccp grains. Simultaneously, the inward diffusion of O2 resulted in Ni– and Cu–enriched cores of Pn and Ccp, respectively. The Cu–enriched core further sulphated into CuSO4, whereas the Ni–S enriched core remained stable at 550 °C. This phenomenon is consistent with the sulphate–leaching experiments (Fig. S2a) and the in–situ XRD characterizations (Figs 3 and 4). The aforementioned results suggest that the sulphation of Ccp was preferential over that of Pn. As shown in Figs 5h and 6h, the distribution of S at the outer layer decreased or disappeared, mainly owing to the decomposition of the outer Fe2(SO4)3 layers into Fe2O3 at 650 °C (Figs S5c and S6c). A clearer and more realistic view of this is provided by comparison with Fig. 5f and i (Fig. 6f and i for Ccp grain).

As shown in Fig. 5k and l, the NiS inner core was oxidised into NiO and Ni x Fe3−x O4−y at 750 °C. There were three layers (NiO–Ni x Fe3−x O4−y –Fe2O3, from inner to outside) in the Pn grain (Fig. S5d). Surprisingly, however, the sulphation of Ni is not been observed in Fig. 5, possibly because a small amount of NiSO4 formed under this continuous–heating condition and the grains were not selected randomly in this work. For the Ccp grains (Fig. 6k and l), there may have been a Cu x Fe3−x O4−y inner layer with a Fe2O3 thin surface after the roasting at 750 °C (Fig. S6d). Another noteworthy phenomenon is that the Ni tended to diffuse outward gradually, as observed by comparing the line–scanning results in Fig. 5h and k (Fig. 5i and l for mapping). Moreover, as shown in Fig. 6k and l, diffuse distributions of Cu, Fe, and O appeared, indicating that the Cu atoms diffused outward more rapidly than the Ni atoms.

Oxidation mechanism of Ni–Cu sulphide ore

Considering the aforementioned results, the reaction sequence of the Ni–Cu sulphide ore during the roasting in air was deduced, as summarised in Table 1. The oxidation mechanism of Pn and Ccp is proposed as follows and shown in Fig. 7. In the temperature range of 350 to 450 °C, the surface–absorbed O2 first contacted and reacted with the mineral grains, and a thin Fe2O3 layer was formed at this stage. Fe and S were preferentially oxidized over Ni and Cu, which was clearly observed and well–investigated. Consequently, the Fe atoms diffused to the surface, while the Ni and Cu atoms migrated into the inner core. Although many authors have observed and investigated this phenomenon, no reasonable theory has been proposed to explain the internal connection between the preferential oxidation of Fe and the opposite diffusion directions of Fe and Ni (or Cu)13,14,15, 17, 18, 22. Recently, researchers used the ab–initio density functional theory to investigate and explain the preferential oxidation of Fe at the Pn and Ccp surface37. And, based on the characterization presented in the present study, this preferential oxidation may have resulted from the chemical–affinity of metals (Fe, Ni and Cu) for oxygen and sulphur38. While the Fe was preferentially oxidized into Fe–O phase on the surface of Pn or Ccp crystal structure, the concentration of Fe–S declined sharply, resulting in the outward migration of Fe atoms. Then the Ni/Cu atoms diffused into the inner core and formed Ni–S or Cu–S phase.

As the temperature increased from 450 to 550 °C, Fe and S were continuously preferentially oxidized over Ni and Cu, but the Fe2O3 remained at the interlayer between the outer Fe2(SO4)3 layer and the inner core (NiS for Pn grain, CuSO4 for Ccp grain) at this stage. A large amount of SO2 gas, which was produced by the oxidation of Fe in the interlayer, diffused outward, possibly reacted with O2 to form SO3, and then transformed the previously formed Fe2O3 layer into the outer Fe2(SO4)3 layer. At this stage, the domain reaction was the sulphation of Fe and Cu, and the NiS in the inner core remained stable.

The sulphation of Ni occurred at a higher temperature (approximately 650–750 °C), and a small amount of NiSO4 was formed at the internal layer between the NiS core and the Fe2O3 outer rim at this stage, owing to the small amount of SO2 concentrate produced by the decomposition of Fe2(SO4)3 and CuSO4. A small part of the CuSO4 decomposed and formed a CuO.CuSO4 rim, yet most of the CuSO4 remained stable in the inner core. Hence, this stage was suitable for the sulphation roasting of nickel concentrate, which simultaneously leached Ni and Cu in water and separated Fe from the Ni–Cu sulphide mineral.

The final stage involved the decomposition of CuO.CuSO4, CuSO4, and NiSO4 and the formation of the spinel phase (M x Fe3−x O4−y , M = Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Mg). The Ni and Cu tended to react with the Fe2O3 to form a stable spinel phase. The high chemical stability of the spinel phase may lead to the formation of chemical potential at the reactive interface, then may have caused the outward diffusion of Cu/Ni and the inward diffusion of Fe at a higher temperature39,40,41,42,43. Moreover, the Cu x Fe3−x O4−y was diffusely distributed in the grain, while the Ni x Fe3−x O4−y was just an internal rim with the inner core of NiO. And it may be due to the difference in cation diffusion rates between Ni and Cu during the roasting process.

In conclusion, the oxidation behaviour of a Ni–Cu sulphide ore, which is closely related to the sulphide–extraction metallurgy process, was thoroughly investigated by in–situ laboratory–based XRD and EDS. A four–step oxidation mechanism, including the preferential oxidation of Fe and S, metal sulphation, the decomposition of sulphates, and the formation of a spinel phase, was proposed according to phase–diagram analysis, TG–DTG analysis, the sulphate–leaching process, and in–situ XRD patterns. The reaction sequence that occurred during the oxidation of the Ni–Cu sulphide ore was summarised. In addition, the EDS elemental distribution demonstrated that the Fe atoms diffused outward and the Ni/Cu atoms migrated toward the inner core during the first three stages, whereas these diffusion processes were opposite at the final stage, possibly because of chemical–affinity of metals (Fe, Ni and Cu) for oxygen and sulphur and the high chemical stability of the spinel phase, respectively. A unique visual characterization of the oxidation mechanism in the Ni–Cu sulphide ore roasting process was performed by a combination of in–situ XRD and EDS. This mechanism may be conducive to an alternative metallurgy process for the Ni–Cu sulphide ore.

Methods

Sample preparation

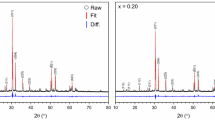

A Ni–Cu sulphide ore sample, which was a product of flotation and originated from Jinchuan Group Ltd., China, was investigated. The powder sample was dried at 100 °C for 24 h and passed over vibrating sieves to obtain an extremely fine powder with a diameter of less than 74 um. XRD analysis indicated that the sample was composed of Pn, magnetite, Ccp, pyrrhotite, lizardite, pyrite, and quartz. XRD quantitative phase analysis (QPA) was performed using the Rietveld refinement method with the TOPAS software44,45,46,47. The Rietveld refinement of the diffraction pattern resulted in good–quality fits with a goodness of fit (Gof) of nearly 2, as shown in Fig. S1. The results of the XRD quantitative phase analysis of the Ni–Cu sulphide ore sample are presented in Table 2. As shown in Table 3, the content of the major metallic elements (Fe, Ni, Cu) in the sample was determined by X–ray fluorescence (XRF), inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP–AES, for short), and XRD analyses.

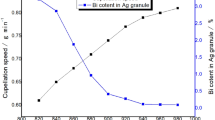

TG analysis and oxidative roasting–water leaching experiments

TG analysis was performed to evaluate the oxidation behaviour of Ni–Cu sulphide ore powder samples using a TG analyser (NETZSCH STA 449 F3 Jupiter) at different heating rates (5, 10, and 20 °C/min) in air. 2 g of the Ni–Cu sulphide ore powder sample was put into a crucible (30 mm × 70 mm) and then the crucible was placed in a muffle furnace, which was heated to a target temperature (from 100 to 900 °C in intervals of 50 °C) at a rate of 5 °C/min and maintained for 30 min. The calcines were then leached in 150 mL of water at 80 °C for 2 h to evaluate the amount of sulphate species formed during the oxidative–roasting process. After filtration, the filtrate was analysed by ICP–AES.

In–situ XRD (full–pattern scanning and PSD fixed model)

In–situ laboratory–based XRD experiments were performed using a laboratory X–ray powder diffractometer (Bruker D8 ADVANCE, with Cu Kα1 radiation). An Anton Paar XRK 900 reactor chamber with a Macor sample holder, which was designed for the in–situ XRD investigation of solid–state and solid–gas reactions at temperatures ranging from 25 to 900 °C, was fitted to the diffractometer. The powder sample rested upon a ceramic sieve (pore size of 0.2 mm), so that reactive gas could penetrate the sample and sample holder. XRK 900 was connected to a TCU 750 temperature–control unit. The heating procedure and measuring parameters were set using the control software of the X–ray diffractometer. The in–situ XRD experiments focused on the oxidative–roasting process of the Ni–Cu sulphide ore sample under a 40 mL/min flow of air steam.

For the full–pattern scanning model of the in–situ XRD, the sample was heated from 25 to 900 °C at 5 °C/min. XRD patterns were collected at different temperatures (every 50 °C from 100 to 900 °C °C) under the isothermal condition. To ensure that the reactions approach chemical equilibrium, a delay of 30 min was set for the data collections. The patterns were recorded in the 2θ range of 20 to 65° with a step size of 0.02° and a counting time of 1 s per step. The diffraction patterns were analysed by Rietveld refinement using TOPAS software44,45,46,47, allowing phase abundances to be quantified.

For the PSD fixed model of the in–situ XRD, the detector was set at a fixed angle to enable the simultaneous detection of a certain 2θ range of the diffraction–pattern data. The sample was roasted from 25 to 900 °C at 5 °C/min and cooled to room temperature at −10 °C/min. A certain 2θ angle (approximately 21°, 28°, 32°, 35°, 56°, and 61°) was set as the starting angle to collect the characteristic diffraction–pattern data instantaneously throughout the heating and cooling process. The opening slit of the detector was set as 2.8° (the maximum value), allowing us to obtain diffraction patterns over the maximum 2θ range. The diffraction data were collected with a counting time of 2 min for each point, yielding temperature resolutions of 10 and 20 °C during the heating and cooling, respectively.

EDS characterization of oxidative–roasting samples

The Ni–Cu sulphide ore sample was evenly sprinkled on four corundum crucibles, forming ultrathin layers of mineral particles at the bottom of each crucible. The four resulting samples were roasted in a muffle furnace in the ambient atmosphere from 25 °C to 450, 550, 650, and 750 °C, respectively, at a heating rate of 5 °C/min. When the given temperature was reached, the samples were removed from the furnace and immediately quenched in liquid nitrogen. The cooling oxidative–powder samples were mounted in epoxy resin. Then, the cured epoxy samples were ground with metallographic abrasive paper and polished on a diamond pad with an oil–based 0.3–µm diamond suspension as the polishing media. Finally, the polished samples were coated with Pt and then characterised using a scanning electron microscope (SU–1500, Hitachi) complemented by an energy–dispersive X–ray detector (Oxford Inca X–Max).

References

Song, X., Wang, Y. & Chen, L. Magmatic Ni–Cu–(PGE) deposits in magma plumbing systems: Features, formation and exploration. Geoscience Frontiers. 2, 375–384, doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2011.05.005 (2011).

Thornhill, P. G. Method of roasting metal sulfide concentrates in a fluidized bed. U.S. patent 2,813,015 (1957).

Thornhill, P. G. Method of roasting metal sulfide concentrates in a fluidized bed. U.S. patent 2,813,016 (1957).

Thornhill, P. G. Fluidized bed roasting of metal sulfide concentrates. U.S. patent 2,930,604 (1960).

Frankiewicz, T. C. Selective sulfation process for partitioning ferrous and non–ferrous values in an ore. U.S. patent 4,110,106 (1978).

Saikkonen, P. J. Process for recovering non–ferrous metal values from ores, concentrates, oxidic roasting products or slags. U.S. patent 4,464,344 (1984).

Dunn, J. G. The oxidation of sulphide minerals. Thermochimica Acta. 300, 127–139, doi:10.1016/S0040-6031(96)03132-2 (1997).

Pandher, R. & Utigard, T. Roasting of nickel concentrates. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B. 41, 780–789, doi:10.1007/s11663-010-9373-5 (2010).

Acres, R. G., Harmer, S. L. & Beattie, D. A. Synchrotron PEEM and ToF–SIMS study of oxidized heterogeneous pentlandite, pyrrhotite and chalcopyrite. Journal of synchrotron radiation. 17, 606–615, doi:10.1107/S0909049510026749 (2010).

Pandher, R., Thomas, S., Yu, D., Barati, M. & Utigard, T. Sulfate formation and decomposition of nickel concentrates. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B. 42, 291–299, doi:10.1007/s11663-010-9466-1 (2011).

Yu, D. & Utigard, T. A. TG/DTA study on the oxidation of nickel concentrate. Thermochimica Acta. 533, 56–65, doi:10.1016/j.tca.2012.01.017 (2012).

Dunn, J. & Kelly, C. A TG/MS and DTA study of the oxidation of pentlandite. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry. 18, 147–154, doi:10.1007/BF01909462 (1980).

Xia, F., Pring, A. & Brugger, J. Understanding the mechanism and kinetics of pentlandite oxidation in extractive pyrometallurgy of nickel. Minerals Engineering. 27–28, 11–19, doi:10.1016/j.mineng.2011.12.001 (2012).

Zhu, H., Chen, J., Deng, J., Yu, R. & Xing, X. Oxidation behavior and mechanism of pentlandite at 973 K (700 °C) in air. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B. 43, 494–502, doi:10.1007/s11663-011-9630-2 (2012).

Yu, D., Utigard, T. A. & Barati, M. Fluidized bed selective oxidation–sulfation roasting of Nickel sulfide concentrate: part I. oxidation roasting. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B. 45, 653–661, doi:10.1007/s11663-013-9958-x (2014).

Tsukada, H., Asaki, Z., Tanabe, T. & Kondo, Y. Oxidation of mixed copper–iron sulfide. Metallurgical Transactions B. 12, 603–609, doi:10.1007/BF02654333 (1981).

Prasad, S. & Pandey, B. D. Alternative processes for treatment of chalcopyrite – A review. Minerals Engineering. 11, 763–781, doi:10.1016/S0892-6875(98)00061-2 (1998).

Perez–Fontes, S., Perez–Tello, M., Prieto–Lopez, L., Brown, F. & Castillon–Barraza, F. Thermoanalytical study on the oxidation of sulfide minerals at high temperatures. Minerals and Metallurgical Processing. 24, 275–283 (2007).

Burger, E., Bourgarit, D., Frotté, V. & Pilon, F. Kinetics of iron–copper sulphides oxidation in relation to protohistoric copper smelting. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry. 103, 249–256, doi:10.1007/s10973-010-0926-2 (2010). 2.

Savinova, Y. A., Popov, V. A., Portov, A. B. & Tsemekhman, L. S. Roasting of a sulfide polymetallic concentrate in a fluidized bed furnace. Russian Metallurgy (Metally). 2014, 351–357, doi:10.1134/S0036029514050115 (2014).

Mitovski, A. et al. Thermal analysis and kinetics of the chalcopyrite–pyrite concentrate oxidation process. Metalurgija. 54, 311–314 (2015).

Razouk, R. I., Kolta, G. A. & Mikhail, R. S. The roasting of copper sulphides. II. Natural copper sulphides. Journal of Applied Chemistry. 15, 191–196, doi:10.1002/jctb.5010150406 (1965).

A. Baba, A. et al. A review on novel techniques for chalcopyrite ore processing. Journal of Mining Engineering and Mineral Processing. 1, 1–16, doi:10.5923/j.mining.20120101.01 (2012).

Prasad, S. & Pandey, B. D. Thermoanalytical studies on copper—iron sulphides. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry. 58, 625–637, doi:10.1023/A:1010108729034 (1999).

Živković, Zi. D., Mitevska, N. & Savović, V. Kinetics and mechanism of the chalcopyrite–pyrite concentrate oxidation process. Thermochimica Acta. 282–283, 121–130, doi:10.1016/0040-6031(96)02883-3 (1996).

Tanabe, T. et al. Oxidation kinetics of dense pentlandite. Transactions of the Japan Institute of Metals. 28, 977–985, doi:10.2320/matertrans1960.28.977 (1987).

Madsen, I. C., Scarlett, N. V. Y. & Whittington, B. I. Pressure acid leaching of nickel laterite ores: anin situdiffraction study of the mechanism and rate of reaction. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 38, 927–933, doi:10.1107/S002188980502813X (2005).

Bhagat, R. et al. In situ synchrotron diffraction of the electrochemical reduction pathway of TiO2. Acta Materialia. 58, 5057–5062, doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2010.05.041 (2010).

Fu, X., Wang, Y. & Wei, F. Phase transitions and reaction mechanism of ilmenite oxidation. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A. 41, 1338–1348, doi:10.1007/s11661-010-0173-y (2010).

Majuste, D., Ciminelli, V. S. T., Eng, P. J. & Osseo–Asare, K. Applications of in situ synchrotron XRD in hydrometallurgy: Literature review and investigation of chalcopyrite dissolution. Hydrometallurgy. 131–132, 54–66, doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2012.10.001 (2013).

Webster, N. A. S. et al. An investigation of goethite–seeded Al(OH)3 precipitation using in situ X–ray diffraction and Rietveld–based quantitative phase analysis. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 43, 466–472, doi:10.1107/S0021889810008484 (2010).

Webster, N. A. S., Pownceby, M. I. & Madsen, I. C. In situ X–ray diffraction investigation of the formation mechanisms of silico–ferrite of calcium and aluminium–I–type (SFCA–I–type) complex calcium ferrites. ISIJ International. 53, 1334–1340, doi:10.2355/isijinternational.53.1334 (2013).

Webster, N. A. S. et al. In situ diffraction studies of iron ore sinter bonding phase formation: QPA considerations and pushing the limits of laboratory data collection. Powder Diffraction. 29(suppl.1), S54–S58, doi:10.1017/S088571561400092X (2014).

Webster, N. A. S. et al. Fundamentals of silico–ferrite of calcium and aluminum (SFCA) and SFCA–I iron ore sinter bonding phase formation: effects of CaO:SiO2 ratio. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B. 45, 2097–2105, doi:10.1007/S11663-014-0137-5 (2014).

Bale, C. W. et al. FactSage thermochemical software and databases. Calphad. 26, 189–228, doi:10.1016/S0364-5916(02)00035-4 (2002).

Wang, H. & Salveson, I. A review on the mineral chemistry of the non-stoichiometric iron sulphide, Fe1−xS(0 ≤ x ≤ 0.125): polymorphs, phase relations and transitions, electronic and magnetic structures. Phase Transitions. 78, 547–567, doi:10.1080/01411590500185542 (2005).

Mkhonto, P. P., Chauke, H. R. & Ngoepe, P. E. Ab initio studies of O2 adsorption on (110) nickel–rich pentlandite (Fe4Ni5S8) mineral surface. Minerals. 5, 665–678, doi:10.3390/min5040516 (2015).

Marakushev, A. A. & Bezmen, N. I. Chemical affinity of metals for oxygen and sulfur. International Geology Review. 13, 1781–1794, doi:10.1080/00206817109475642 (1971).

Kenfack, F. & Langbein, H. Spinel ferrites of the quaternary system Cu-Ni-Fe-O: Synthesis and characterization. Journal of Materials Science. 41, 3683–3693, doi:10.1007/s10853-006-6263-y (2006).

Karpova, T. S., Vasil’ev, V. G., Vladimirova, E. V. & Nosov, A. P. Synthesis of ferrite spinel NiFe2O4 by thermal hydrolysis and its magnetic properties. Inorganic Materials: Applied Research. 3, 107–112, doi:10.1134/S2075113312020086 (2012).

Iliev, M. N. et al. Raman studies of cation distribution and thermal stability of epitaxial spinel NiCo2O4 films. Journal of Applied Physics. 114, 1–5, doi:10.1063/1.4815874 (2013).

Balagurov, A. M. et al. Crystallography Reports. Structural phase transition in CuFe2O4 spinel. 58, 710–717, doi:10.1134/S1063774513040044 (2013).

Liang, X. et al. The valence and site occupancy of substituting metals in magnetite spinel structure Fe3−xMxO4 (M = Cr, Mn, Co and Ni) and their influence on thermal stability: an XANES and TG-DSC investigation. Solid State Sciences. 15, 115–122, doi:10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2012.10.005 (2013).

Rietveld, H. M. Line profiles of neutron powder–diffraction peaks for structure refinement. Acta Crystallographica. 22, 151–152, doi:10.1107/S0365110X67000234 (1967).

Rietveld, H. M. A. profile refinement method for nuclear and magnetic structures. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2, 65–71, doi:10.1107/S0021889869006558 (1969).

Cheary, R. W. & Coelho, A. A fundamental parameters approach to X–ray line–profile fitting. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 25, 109–121, doi:10.6028/jres.002 (1992).

TOPAS v. 4.2 (Bruker AXS Inc., USA, 2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Grant 2014CB643403 from the National Key Program for Basic Research of 973 Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guangshi Li, Hongwei Cheng and Xionggang Lu conceived, designed and coordinated the study; Guangshi Li performed the experiments and processed the data; Hongwei Cheng, Xionggang Lu, Xingli Zou and Qian Xu contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. Xiaolu Xiong, Cong Xu and Changyuan Lu contributed to the discussion of the results as well as to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, G., Cheng, H., Xiong, X. et al. In–situ XRD and EDS method study on the oxidation behaviour of Ni–Cu sulphide ore. Sci Rep 7, 3212 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03290-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03290-y

This article is cited by

-

Efficient Synchronous Extraction of Nickel, Copper, and Cobalt from Low–Nickel Matte by Sulfation Roasting‒Water Leaching Process

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

A Novel Ammonium Chloride Roasting Approach for the High-Efficiency Co-sulfation of Nickel, Cobalt, and Copper in Polymetallic Sulfide Minerals

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.