Abstract

Isolated congenital anosmia (ICA) is a rare condition that is associated with life-long inability to smell. Here we report a genetic characterization of a large Iranian family segregating ICA. Whole exome sequencing in five affected family members and five healthy members revealed a stop gain mutation in CNGA2 (OMIM 300338) (chrX:150,911,102; CNGA2. c.577C > T; p.Arg193*). The mutation segregates in an X-linked pattern, as all the affected family members are hemizygotes, whereas healthy family members are either heterozygote or homozygote for the reference allele. cnga2 knockout mice are congenitally anosmic and have abnormal olfactory system physiology, additionally Karstensen et al. recently reported two anosmic brothers sharing a CNGA2 truncating variant. Our study in concert with these findings provides strong support for role of CNGA2 gene with pathogenicity of ICA in humans. Together, these results indicate that mutations in key olfactory signaling pathway genes are responsible for human disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Isolated congenital anosmia (OMIM 107200) is a rare condition where patients have no recollection of ever being able to smell1. Unlike syndromic forms of anosmia, ICA patients have no additional symptoms, and no other underlying disease-causing condition can be identified1. ICA usually occurs sporadically, although some familial cases have previously been reported1,2,3,4,5,6. While several causal genes have been identified for syndromic cases of anosmia (such as Kallmann syndrome and Bardet-Biedl syndrome)7,8,9, the underlying genetic architecture of ICA is barely known. Since Glaser et al. first reported ICA as a potentially hereditary trait nearly 100 years ago10, there have been few candidate genes identified as the potential genetic cause for ICA3, 6, 11,12,13. Moreover, most reported anosmia cases are inherited through autosomal dominant patterns2, 14, however, in some instances, it is an X-linked trait3, 6, 10. For instance, In 2015, Karstensen et al. for the first time reported a hemizygous nonsense mutation in CNGA2 in an ICA family (two brothers) with an X-linked pattern of inheritance3, but the lack of additional family members precluded definitive assignment of this gene as associated with this disease. CNGA2 encodes the alpha subunit of a cyclic nucleotide-gated olfactory channel. Interestingly, deletion of any of the three main olfactory transduction components in mice, namely Gnal 15, Adcy3 16 and Cnga2 17, causes significant reduction of physiological responses to odorants consistent with ICA phenotype. Also, Alkelai et al.6 reported a family with congenital general anosmia segregating an X-linked missense mutation in the TENM1 gene6. Together, these studies indicate that ICA is very heterogeneous and that rare pathogenic variants in multiple genes may contribute to the phenotype.

Here, we report exome-sequencing results of a large consanguineous Iranian family segregating ICA in an X-linked pattern of inheritance. We identified a novel stop-gain mutation in CNGA2 gene that in concert with Cnga2 knockout mice and results of the Karstensen et al. study3 further supports the role of CNGA2 in the pathogenesis of ICA in humans.

Results

Exome sequencing results

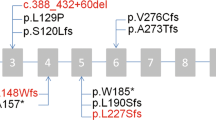

Whole-exome sequencing to a mean coverage of above 70X was performed (Supplemental Fig. 1). Using Varseq software, we identified 88,042 variants shared in the all sequenced family members (10 individuals; Table 1) that have a genotype quality score above 20. Since the disease model of ICA based on the pedigree was consistent with autosomal recessive or X-linked, we filtered for homozygous or hemizygous variants that are found in all the five affected individuals, but in none of the healthy controls. 16 variants passed this filtering step of which only CNGA2.577C > T has minor allele frequency (MAF) less than 0.01 or absent in the public database (dbSNP Common 144 (Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphism, NCBI), 1000 Genome project phase 3 (www.1000genomes.org), Exome Aggregation Consortium version 0.3 (EXaC), Exome Variant Server; NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), and the Iranian genome project (http://irangenes.com/data-2/). This loss of function mutation occurs in exon 6 of CNGA2 gene, is rare (unreported in public databases) and highly conserved (Fig. 1C) by ConSurf 18.

(A) Pedigree structure of ICA family. The proband is noted by an arrow. Family members for which whole exome sequencing has been performed are noted by a star above the individual’s symbol. The genotype of identified variant for family members for which DNA sample was available is mentioned below the individual’s symbol. (B) Sanger sequencing traces (CC/TGA) showing the c.950 C > T (p.Arg193*) mutation in exon 6 of the CNGA2 gene. The segregation of this mutation has been confirmed in 12 available DNA samples (Five affected and seven unaffected individuals) from this family. (C) The amino-acid sequence CNGA2 (pArg193*) colored according to the conservation scores. Conservation scores were calculated by ConSurf tool18. ConSurf estimates the evolutionary conservation of amino acid residues in a peptide based on the phylogenetic relations between homologous sequences as well as amino acid’s structural and functional importance.

Segregation analyses

We confirmed this variant by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 1B) and showed that the variant co-segregates with the disease as all the five affected individuals have a hemizygous mutation (one mutation on the X chromosome in males), while unaffected family members are heterozygous or homozygous for the reference allele.

Discussion

Anosmia occurs mostly in the middle aged and elderly; affecting up to 5% of individuals over the age of 45 years old19, 20. Rarely, however, it can occur as a congenital condition (prevalence 1 in 10,000)21 (Isolated Congenital Anosmia) (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] % 107200). Few candidate genes have been identified as potential causal genes for ICA in humans3, 6, 11,12,13, 22. For instance, Karstensen et al.3 reported a mutation in CNGA2 in two brothers with an X-linked pattern of ICA3. However, the lack of additional family members precluded definitive assignment of this gene as associated with this disease. Also, Alkelai et al.6 reported a family with congenital general anosmia segregating an X-linked missense mutation in the TENM1 gene6. In the present study, we employed whole-exome sequencing to identify the underlying genetic variants associated with ICA in a large Iranian family (five affected and five un-affected family members). The identified loss of function variant has not been reported in the public databases and falls within exon 6 of CNGA2 gene. We confirmed the segregation of the variant with Sanger sequencing and showed all five affected individuals are hemizygous for this variant, whereas all healthy individuals are either heterozygous or homozygous for the reference allele. Furthermore, one may speculate that the healthy female individuals, who carry this mutation, show to some extent hyposmia. However, the results of smell test on the three apparently healthy females, who carry CNGA2 mutation as well, show that they fall within normosmia category (score of 19 to 24 of smell test) (Table 1). Moreover, due to the lack of brain MRI data, we cannot verify whether there is a defect in olfactory structures (i.e. olfactory bulb and olfactory sulci) in the affected individuals. There have been also contradicting reports on the ICA characterization in humans. Generally ICA is characterized by the absence or severe hypoplasia of olfactory bulbs23,24,25,26, however, brain MRI studies of ICA patients by Karstensen et al.3 and Ghadami et al. 2004 show that there is an apparently normal or slightly reduced olfactory structure in ICA. These studies suggest the existence of an ICA sub-phenotype characterized by an apparently normal olfactory structure3, 5.

Olfactory receptors are the largest group of orphan G protein-coupled receptors27. The CNG olfactory channels are made of alpha subunit and two modulatory subunits, encoded by CNGA2, CNGB1b and CNGA4, respectively28, 29. The alpha subunit of CNG channel is critical for olfactory sensory neurons to generate an odor-induced action potential. Knockout mice models lacking these essential CNG channel subunits strongly support the critical role of this canonical pathway in olfactory signaling15,16,17. Cnga2 knockout mice are congenitally anosmic and have severely impaired olfactory function17. Moreover, CNGA2 is highly expressed in the olfactory sensory neurons of zebrafish, mouse and humans30,31,32. Our study together with Karstensen et al.3 and Cnga2 knock-out mice model strongly support the role of CNGA2 gene in pathogenicity of familial cases of ICA. Together, these results indicate that mutations in key olfactory signaling pathway genes are responsible for human disease.

Material and Methods

Family description

All participants, or their legal guardian, provided written and informed consent. The institutional review boards of Department of Medical Genetics, Tarbiat Modares University, and Stanford University reviewed and approved the project. All methods in this study were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines and regulations. The institutional review board of Stanford University approved the experimental protocols. The family pedigree is shown in Fig. 1A. All the affected individuals underwent clinical and physical examination at the Department of Medical Genetics, DeNA Laboratory, Tehran, Iran.

For assessment of olfactory function in affected individuals, we used Iran Smell Identification Test (Iran-SIT)33 which is a commercially Iranian adopted version of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT)34. In this test, the familiar smells in Iranian environment and culture is used to test the function of an individual’s olfactory function in a scale of 1 to 24. A score of 1–9 indicates anosmic; 9–13 severe microsmia; 13–17 mild microsmia, and 19–24 normosmia state (Table 1). The smell test has been performed on all the available affected individuals. For the apparently healthy individuals, smell test has been done only on the three available individuals (II-10, III-3 and III-7 of Table 1 and Fig. 1A).

Exome sequencing and variants calling

Library preparation was performed using KAPA HyperPlus kit followed by exome capture using the IDT xGen® Exome Research Panel v1.0. Briefly, 0.4 μg of gDNA was fragmented to a peak size of 150–200 bp using the KAPA Frag enzyme. The fragmented genomic DNA were end-repaired, A-tailed, ligated to indexing-specific paired-end adaptors and PCR amplified according to manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR reactions were cleaned using the Agencourt AMPure XP beads. To capture exonic regions, 500 ng of pooled libraries (8 libraries per pool) was hybridized to biotinylated oligonucleotides for 4 hours at 65 °C. The captured libraries were pulled down using Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin M-270 (Invitrogen). A post-capture PCR was then performed to amplify the captured libraries and to add the barcode sequences for multiplex sequencing for 12 cycles. Afterwards, amplified libraries were purified with AmpPure XP Beads. Qubit fluorometer and Bioanalyzer high sensitivity chips were used to determine the final concentration of each captured library. The pooled libraries were paired-end sequenced on two lane of Illumina HiSeq4000 at the Stanford Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine according to standard protocols.

Bioinformatics analyses

DNA libraries were processed and analyzed using the Roche Sequencing Solutions (Bina Technologies version 2.7.9) whole-exome analysis workflow with default settings. Briefly, libraries were mapped with BWA mem 0.7.5 software to human genome (hg19 version), and then realigned around indels with GATK IndelRealigner. Next, base recalibration was performed with GATK BaseRecalibrator taking into account the read group, quality scores, and cycle and context covariates. Variants were called with GATK HaplotypeCaller with the parameters–variant_index_ type LINEAR–variant_index_parameter 128000. VQSR was used to recalibrate the variants, first with GATK VariantRecalibrator and then ApplyRecalibration. Variant filtering and annotation was done using Golden Helix VarSeq Version 1.1 software (http://goldenhelix.com/products/VarSeq/). After importing the variant call files (gVCF files) of each member of the family, the variants were organized by pedigree. Using the 1000 genomes variant frequencies (phase 1), the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) variant frequency database version 0.3 (Cambridge, MA), and the NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (https://esp.gs.washington.edu/drupal/) V2 Exome Variant Frequencies, rare variants (minor allele frequency <1%) were filtered. Variants were then classified according to whether they were deemed to be coding.

Sanger sequencing

To validate the variant and to verify its segregation in the family, we used 5′ TCTACATTGCGGACCTCTTC3′ as forward primer and 5′ TCTAAGAGAACACCCCGAGA3′ as reverse primer for PCR amplification of the variant sequence. PCR amplification was performed using following reagents: REDTaq ReadyMix PCR Reaction Mix (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis) 25 ul, 1 ul forward primer (10 uM), 1 ul reverse primer (10 uM), 1 ul DNA (50 ng/ul), and 22 ul of water per PCR reaction. An initial denaturation step at 94° for 3 min was followed by 35 cycles of 94° for 30 sec, 57° for 30 sec, 72° for 30 sec, and the process completed by a final extension at 72° for 7 min. The PCR amplification resulted in a single DNA band on a standard 1% Agarose Gel, and was purified by Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Inc) before submitting for Sanger sequencing. The reverse primer 5′ TCTAAGAGAACACCCCGAGA 3′ was used as sequencing primer. Sanger sequencing was carried out by the Stanford PAN facility using ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer.

References

Karstensen, H. G. & Tommerup, N. Isolated and syndromic forms of congenital anosmia. Clin Genet 81, 210–5 (2012).

Lygonis, C. S. Familiar absence of olfaction. Hereditas 61, 413–6 (1969).

Karstensen, H. G., Mang, Y., Fark, T., Hummel, T. & Tommerup, N. The first mutation in CNGA2 in two brothers with anosmia. Clin Genet 88, 293–6 (2015).

Ghadami, M. et al. Isolated congenital anosmia locus maps to 18p11.23-q12.2. J Med Genet 41, 299–303 (2004).

Ghadami, M. et al. Isolated congenital anosmia with morphologically normal olfactory bulb in two Iranian families: a new clinical entity? Am J Med Genet A 127A, 307–9 (2004).

Alkelai, A. et al. A role for TENM1 mutations in congenital general anosmia. Clin Genet 90, 211–9 (2016).

Dode, C. et al. Loss-of-function mutations in FGFR1 cause autosomal dominant Kallmann syndrome. Nat Genet 33, 463–5 (2003).

Forsythe, E. & Beales, P. L. Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 21, 8–13 (2013).

Janssen, S. et al. Mutation analysis in Bardet-Biedl syndrome by DNA pooling and massively parallel resequencing in 105 individuals. Hum Genet 129, 79–90 (2011).

Glaser, O. Hereditary Deficiencies in the Sense of Smell. Science 48, 647–8 (1918).

Moya-Plana, A., Villanueva, C., Laccourreye, O., Bonfils, P. & de Roux, N. PROKR2 and PROK2 mutations cause isolated congenital anosmia without gonadotropic deficiency. Eur J Endocrinol 168, 31–7 (2013).

Richards, M. R. et al. Phenotypic spectrum of POLR3B mutations: isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism without neurological or dental anomalies. J Med Genet 54, 19–25 (2017).

Feldmesser, E. et al. Mutations in olfactory signal transduction genes are not a major cause of human congenital general anosmia. Chem Senses 32, 21–30 (2007).

Joyner, R. E. Olfactory acuity in an industrial population. J Occup Med 5, 37–42 (1963).

Belluscio, L., Gold, G. H., Nemes, A. & Axel, R. Mice deficient in G(olf) are anosmic. Neuron 20, 69–81 (1998).

Bakalyar, H. A. & Reed, R. R. Identification of a specialized adenylyl cyclase that may mediate odorant detection. Science 250, 1403–6 (1990).

Brunet, L. J., Gold, G. H. & Ngai, J. General anosmia caused by a targeted disruption of the mouse olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel. Neuron 17, 681–93 (1996).

Ashkenazy, H., Erez, E., Martz, E., Pupko, T. & Ben-Tal, N. ConSurf 2010: calculating evolutionary conservation in sequence and structure of proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res 38, W529–33 (2010).

Bramerson, A., Johansson, L., Ek, L., Nordin, S. & Bende, M. Prevalence of olfactory dysfunction: the skovde population-based study. Laryngoscope 114, 733–7 (2004).

Landis, B. N., Konnerth, C. G. & Hummel, T. A study on the frequency of olfactory dysfunction. Laryngoscope 114, 1764–9 (2004).

Quint, C. et al. Patterns of non-conductive olfactory disorders in eastern Austria: a study of 120 patients from the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at the University of Vienna. Wien Klin Wochenschr 113, 52–7 (2001).

Keydar, I. et al. General olfactory sensitivity database (GOSdb): candidate genes and their genomic variations. Hum Mutat 34, 32–41 (2013).

Yousem, D. M., Geckle, R. J., Bilker, W., McKeown, D. A. & Doty, R. L. MR evaluation of patients with congenital hyposmia or anosmia. AJR Am J Roentgenol 166, 439–43 (1996).

Huart, C. et al. The depth of the olfactory sulcus is an indicator of congenital anosmia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 32, 1911–4 (2011).

Abolmaali, N. D., Hietschold, V., Vogl, T. J., Huttenbrink, K. B. & Hummel, T. MR evaluation in patients with isolated anosmia since birth or early childhood. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 23, 157–64 (2002).

Qu, Q. et al. Diagnosis and clinical characteristics of congenital anosmia: case series report. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 39, 723–31 (2010).

Monahan, K. & Lomvardas, S. Monoallelic expression of olfactory receptors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 31, 721–40 (2015).

Bradley, J., Reisert, J. & Frings, S. Regulation of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15, 343–9 (2005).

Nache, V. et al. Deciphering the function of the CNGB1b subunit in olfactory CNG channels. Sci Rep 6, 29378 (2016).

Saraiva, L. R. et al. Hierarchical deconstruction of mouse olfactory sensory neurons: from whole mucosa to single-cell RNA-seq. Sci Rep 5, 18178 (2015).

Saraiva, L. R. et al. Molecular and neuronal homology between the olfactory systems of zebrafish and mouse. Sci Rep 5, 11487 (2015).

Olender, T. et al. The human olfactory transcriptome. BMC Genomics 17, 619 (2016).

Taherkhani, S. et al. Iran Smell Identification Test (Iran-SIT): a Modified Version of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) for Iranian Population. Chemosensory Perception 8, 8 (2015).

Doty, R. L., Shaman, P., Kimmelman, C. P. & Dann, M. S. University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: a rapid quantitative olfactory function test for the clinic. Laryngoscope 94, 176–8 (1984).

Acknowledgements

M.R.S. is supported by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). Work in the Snyder lab is supported by NIH grants to M.P.S. (1P50HG00773501 and 8U54DK10255602). We thank the Stanford Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine for their sequencing services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R.S., I.J., J.B., M.G. and M.P.S. designed and review the study. M.R.S., M.P.S. and M.G. wrote the paper. M.G., S.M., F.B. assisted in collection of samples, clinical evaluation of affected individuals, and DNA isolation. M.R.S. and I.J. performed and analyzed the WES and Sanger sequencing data. All the authors approve the content of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

M.P.S. is a cofounder of Personalis and a member of the scientific advisory boards of Personalis and Genapsys.

Additional information

Accession Codes: Next generation sequencing data (WES) is available at SRA (NCBI) through SRP106899 and Bioproject PRJNA386047.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sailani, M.R., Jingga, I., MirMazlomi, S.H. et al. Isolated Congenital Anosmia and CNGA2 Mutation. Sci Rep 7, 2667 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02947-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02947-y

This article is cited by

-

Matters Arising: Is congenital anosmia protective for Parkinson’s disease triggered by pathogenic entrance through the nose?

npj Parkinson's Disease (2023)

-

Is congenital anosmia protective for Parkinson’s disease triggered by pathogenic entrance through the nose?

npj Parkinson's Disease (2022)

-

Single-molecule imaging with cell-derived nanovesicles reveals early binding dynamics at a cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel

Nature Communications (2021)

-

The cyclic AMP signaling pathway in the rodent main olfactory system

Cell and Tissue Research (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.