Abstract

The recent global challenges to prevent and treat fungal infections strongly demand for the development of new antifungal strategies. The structurally very similar cysteine-rich antifungal proteins from ascomycetes provide a feasible basis for designing new antifungal molecules. The main structural elements responsible for folding, stability and antifungal activity are not fully understood, although this is an essential prerequisite for rational protein design. In this study, we used the Neosartorya fischeri antifungal protein (NFAP) to investigate the role of the disulphide bridges, the hydrophobic core, and the N-terminal amino acids in the formation of a highly stable, folded, and antifungal active protein. NFAP and its mutants carrying cysteine deletion (NFAPΔC), hydrophobic core deletion (NFAPΔh), and N-terminal amino acids exchanges (NFAPΔN) were produced in Pichia pastoris. The recombinant NFAP showed the same features in structure, folding, stability and activity as the native protein. The data acquired with mass spectrometry, structural analyses and antifungal activity assays of NFAP and its mutants proved the importance of the disulphide bonding, the hydrophobic core and the correct N-terminus for folding, stability and full antifungal function. Our findings provide further support to the comprehensive understanding of the structure-function relationship in members of this protein group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent global challenges to prevent and treat fungal infections for human welfare require the development of novel antifungal strategies against moulds1. The cysteine-rich antifungal proteins from filamentous ascomycetes (AFPs) provide a feasible basis for the rational design and development of new bio-pesticides, preservatives and drugs with improved activity, efficacy, fungal-selectivity, and low-cost production2,3,4,5. The members of this protein group show different antifungal spectra and mechanisms of action on opportunistic human, animal, plant and foodborne pathogenic filamentous fungi6,7,8,9, but interestingly, they exhibit remarkably similar β-barrel topology constituting five highly twisted antiparallel β-strands10,11,12,13,14. This structure is stabilized by three to four disulphide bridges, which provide stability against protease degradation, high temperatures and within a broad pH range6. In spite of the available experimental knowledge about their structure10,11,12,13,14, the main structural elements which coordinate the proper folding, and hence are responsible for the high-stability and antifungal activity have not been fully understood. However, distinction of these “essential” determinants from the other “non-essential” designable structural elements is a prerequisite for rational modifications to improve the activity and fungal-specificity of these proteins, which are strongly requested for novel antifungal strategies. The importance of disulphide bonds and the correct cleavage of the leader sequence from the N-terminus for structural integrity and antifungal activity have been already observed in this protein family11, 12, 15, 16.

The tertiary structure of AFPs is similar to the β-defensin(-like) peptides but they possess a hydrophobic core12. In the lack of a distinct hydrophobic core, the folded structure of β-defensins is stabilized by intramolecular disulphide bonds between cysteine residues and these also catalyse the proper folding of antimicrobial active structure17, 18. It is well-known that the hydrophobic core of a protein is responsible for stability, and coordinates the folding and structural formation19,20,21. Mutations in the hydrophobic core affect the stability and the correct protein folding22. Furthermore, the first five N-terminal residues of β-defensins facilitate the proper folding and the formation of canonical disulphide bond pattern17. Single N-terminal amino acid mutations or lack of the N-terminal residues causes structural rearrangements23 and/or changes in the antimicrobial specificity, efficacy or toxicity24.

The Neosartorya fischeri NRRL 181 isolate secretes a representative of AFPs, the Neosartorya fischeri antifungal protein (NFAP)25. NFAP is synthesised as a preproprotein which contains both a signal sequence for secretion and a prosequence that is removed before or during protein release into the supernatant25. We successfully used a Pichia pastoris heterologous expression system to produce high amounts of folded and active recombinant NFAP, which has the same antifungal activity as the native NFAP9.

In this study, we wanted to prove our assumption that distinct structural elements contribute to the secondary structure formation, proper folding, stability and antifungal activity of AFPs from ascomycetes like NFAP. To achieve this objective, we produced recombinant NFAP mutants in P. pastoris that vary in disulphide bridge formation (NFAPΔC), the hydrophobic core (NFAPΔh) and the N-terminus (NFAPΔN) (Table 1). In NFAPΔC the disulphide bridges, and in NFAPΔh the hydrophobic core were destroyed by amino acids substitutions. The NFAPΔN mutant carried three exchanges of the first five N-terminal amino acids of the mature protein. The folding property, structural stability, and antimicrobial activity of these NFAP mutants were investigated by thermal unfolding experiments, antifungal susceptibility tests, and functional tests and were compared with the wild-type NFAP.

Results

Homology modelling suggested disrupted structure and disturbed folding of NFAPΔC, NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN

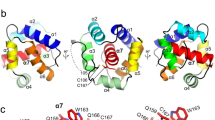

In silico homology modelling experiments can reveal the contribution of the disulphide bonding, the hydrophobic core and the N-terminus to formation of correct secondary structure and folding of NFAP. Hence, we analysed potential structural changes in NFAP when these structural elements are disturbed by amino acid replacement. The in silico predicted tertiary structure of NFAP contains five antiparallel β-strands (constituted by E2-C7, T13-K17, T22-K26, N40-D45, K50-D54) connected with four loops (F8-N12, I18-K21, C27-G39, S46-R49) (Fig. 1). This folded β-barrel structure is stabilized by three intramolecular disulphide bridges between C7-C35, C14-C42 and C27-C53 in an abcabc bonding pattern (Fig. 1). NFAP has an amphipathic surface (Supplementary Fig. S1a), alternating positively- and negatively-charged patches (Supplementary Fig. S1b) and a hydrophobic core constituted by Y3, Y16, I18, Y23, Y44 (Fig. 1). The disulphide-bonded six cysteines are well protected in the centre of this hydrophobic core. Replacements of all cysteines to tyrosines (C7Y, C14Y, C27Y, C35Y, C42Y, C53Y) abrogate the presence of the disulphide bridges (NFAPΔC, Table 1 and Fig. 1). Substitutions of tyrosines at the position of 3, 16, 23, 44 and the isoleucine at the position of 18 to serines (Y3S, Y16S, Y23S, Y44S, and I18S) destruct the hydrophobic core of the molecule (NFAPΔh, Table 1 and Fig. 1). The hydrophilicity of the N-terminal region can be increased by L1G, Y3W and G5A substitutions (NFAP∆N, Table 1 and Fig. 1), which results in a more hydrophobic N-terminal β-strand. However, these amino acid substitutions do not dramatically change the net charge and the grand average of hydropathy (GRAVY) value of the protein (Table 1), but based on the in silico homology modelling data they could impair the disulphide bridge formation26, secondary structure and folded state of NFAP (Fig. 1). The loss of one β-strand, the disturbed disulphide bonding and folding indicate the possibility of significant structural changes in all mutants (Fig. 1).

Predicted tertiary structure of NFAP, NFAPΔC, NFAPΔh, NFAPΔN. The hydrophobic core constituting amino acids are indicated by light blue. Cysteines and the possible disulphide bridges are marked with yellow and yellow line. Amino acid substitutions are indicated in red. The putative structures are highly reliable: Based on the Ramachandran plot analysis37, 94.5% and 5.5% of the residues are in the favoured and allowed regions at NFAP; and 98.2% and 1.8% at NFAPΔC, NFAPΔh, and NFAPΔN. The.pdb files of the structures are available in the Dataset 1–4. NFAP: Neosartorya fischeri NRRL 181 antifungal protein; NFAP∆C: cysteine deletion NFAP mutant; NFAP∆h: hydrophobic core deletion NFAP mutant; NFAP∆N: N-terminal amino acids exchanged NFAP mutant.

Pichia pastoris KM71H produced NFAP and its mutants

To prove the structural and functional disruption by distinct amino acid substitutions, we produced NFAP and its mutants in P. pastoris KM71H (Supplementary Fig. S2). The average yield of purified NFAP, NFAPΔh, and NFAPΔN was 11.27 ± 4.65 mg/l (n = 3), 29.10 ± 0.77 mg/l (n = 3) and 7.62 ± 0.09 mg/l (n = 2), respectively. The NFAPΔC was degraded during its expression. Degradation of NFAPΔC became evident in sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gels (Supplementary Fig. S3) and did not allow a molar mass determination. To prove the presence of the degradation products of NFAPΔC in the culture broth of P. pastoris KM71H, the different molecular weight fractions of the ferment broth were subjected to tryptic digestion to allow the identification of defined peptide fragments originating from NFAPΔC by mass spectrometric (MS) analysis. These molecular mass data were then compared with the NFAPΔC sequence. Nine characteristic peptide fragments could be identified in the >10 kDa fraction which covered 74% of the NFAPΔC sequence (Supplementary Table S1). The identification of both the N- and C-terminal fragments of NFAPΔC proved that the protein was expressed in a correctly processed form and let us assume that it was degraded by extracellular proteases. The investigation of the <3 kDa fraction verified our assumption, that this fraction possibly contained the peptide fragments from the degraded NFAPΔC: We detected eight characteristic peptide fragments in it (Supplementary Table S1). The N-terminal YDFRH peptide fragment was not detectable in the fractions below <10 kDa, possibly due to its weak peak intensity. This result clearly indicates that NFAPΔC is not stable in the absence of the disulphide bridges, and is supposedly more prone to easy degradation by extracellular proteases.

Mass spectrometry and RP-HPLC indicated truncations and structural variants of NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN

NFAP, NFAPΔh, and NFAPΔN were identified by capillary electrophoresis electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (CE-ESI-MS). The calculated and measured monoisotopic molecular masses from independent expressions are listed in Table 2. The NFAP purified from four days cultivation broths of P. pastoris KM71H proved to be homogeneous and correctly maturated, and the measured molecular mass corresponded to the calculated mass of the protein that exhibits oxidized cysteines. This unambiguously indicated that all three disulphide bonds were formed (Table 2). In contrast, differently N- and C-terminal truncated, but disulphide bond-stabilized forms of NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN were present in the purified samples in addition to the full-length mature protein mutants (Table 2). Mass spectrum extraction analysis of the full-length NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN revealed that these NFAP mutants apparently showed different structures (Supplementary Fig. S4), and this could also be observed with their truncated variants (data not shown). This result indicates that NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN were expressed in unordered states before being stabilized by random disulphide bridges. The integrity of the mutant proteins was also examined by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). While the NFAP sample proved to be intact (Fig. 2) and to exist in a single well-folded state, NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN samples were degraded and showed several different structures (Fig. 2). The structural alterations were more prominent in NFAPΔN than in NFAPΔh (Fig. 2). The RP-HPLC results further strengthen our assumption that these NFAP mutants are unordered and contain randomly matched disulphide bonds.

RP-HPLC chromatogram of recombinant NFAP, NFAPΔh, and NFAPΔN. Compared to NFAP, the NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN samples showed degradation and structural alterations, which were more prominent in NFAPΔN than in NFAPΔh. NFAP: recombinant Neosartorya fischeri NRRL 181 antifungal protein; NFAP∆h: hydrophobic core deletion NFAP mutant; NFAP∆N: N-terminal amino acids exchanged NFAP mutant.

ECD spectroscopy indicated unordered secondary structure of NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN

The secondary structure of recombinant NFAP, NFAPΔh, and NFAPΔN and the thermal stability of recombinant NFAP were investigated by ECD spectroscopy and the results were compared with NFAP from the native producer N. fischeri NRRL 18125. ECD spectra of the native and recombinant NFAP were identical at 25 °C (Fig. 3a) indicating that their secondary structures are the same. These spectra had two maxima at 202 nm and 228 nm with a shoulder at 195 nm and a low intensity minimum centred at 217 nm. The maximum at 202 nm emerged from contributions from the spectral transitions of disulphide bridges. The maximum at 228 nm was mainly attributed to the disulphide bridges while the shoulder at 195 nm and the low intensity minimum at 217 nm indicated β-sheet conformation. Similar spectral features were reported previously for the homologous Penicillium chrysogenum antifungal protein (PAF)14 and other β-structured proteins which contain disulphide bridges27. Deconvolution of ECD spectra of native and recombinant NFAP revealed, that the difference between the secondary structure of the two proteins is not higher than 3% (Supplementary Table S2). In the case of NFAP, 3% accounts for less than two residues, therefore it can be assumed that the structures of the two proteins are essentially the same. Spectra of NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN reflected the complete loss of an ordered secondary structure and suggested the presence of various disulphide bond patterns. Thermal unfolding curves (Fig. 3b) indicated that unfolding was not complete in the 25 °C–95 °C temperature range. These curves did not present the usual sigmoidal shape; therefore, the exact determination of the melting temperature (Tm) of the protein structure was not possible. Nevertheless, the native fold of NFAP appeared to be completely intact below 60 °C, which reflected the remarkable stability of this protein.

ECD spectra and thermal unfolding of NFAP, NFAPΔh, and NFAPΔN. (a) ECD spectra of native NFAP (black), recombinant NFAP (red), NFAPΔh (blue) and NFAPΔN (green) mutants recorded at 25 °C. (b) Thermal unfolding of native NFAP (black) and recombinant NFAP (red) followed by ECD spectroscopy at 228 nm. NFAP: native and recombinant Neosartorya fischeri NRRL 181 antifungal protein; NFAP∆h: hydrophobic core deletion NFAP mutant; NFAP∆N: N-terminal amino acids exchanged NFAP mutant.

NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN showed changes in the antifungal activity, thermal, pH and salt tolerance

The antifungal activity, thermal, pH and salt tolerance of the investigated proteins were tested in a broth microdilution assay using the NFAP-sensitive Aspergillus nidulans FGSC A4 as test organism. Compared to the ordered NFAP, the unordered NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN showed no or significantly reduced antifungal activity against A. nidulans FGSC A4, respectively (Fig. 4a). Surprisingly, five microgram NFAPΔN reduced the growth of the test organism to 68 ± 4.7% (Fig. 4a), whereas the same amount of NFAP proved to be inactive. A dose-dependent inhibitory activity was observed for NFAP, and in contrast to this, NFAPΔN reduced the growth with ca. 33%, independently of its applied amount (Fig. 4a). The difference between the antifungal activity of NFAP and NFAPΔN was significant at the applied amount of 5, 20 and 40 μg (Fig. 4a). NFAPΔN showed same tolerance characteristics to heat and pH as NFAP (Fig. 4b,c), but proved to be less salt-tolerant (Fig. 4d). Temperature treatment at 50 °C did not cause significant reduction in the antifungal activity of NFAP and NFAPΔN, but both proteins were inactive after treatment at 100 °C (Fig. 4b). NFAP and NFAPΔN were similarly pH sensitive (Fig. 4c). They showed the highest activity at slightly basic pH 8.0 and they were less active at slightly acidic pH 6.0 (Fig. 4c). Whilst 50–100 mM NaCl, and 25–100 mM MgSO4 impaired the antifungal activity of NFAP in a dose-dependent manner, presence of 25 mM NaCl had no influence (Fig. 4d). In contrast to this, NFAPΔN readily was inactivated by 25 mM NaCl or MgSO4. NFAPΔh was inactive under all conditions tested (Fig. 4a–d).

Antifungal activity of recombinant NFAP, NFAPΔh, NFAPΔN in broth microdilution tests. (a) Growth of Aspergillus nidulans FGSC A4 at pH 7.0 in the presence of 2.5–40 μg NFAP, NFAPΔh, and NFAPΔN; and with 20 μg of NFAP, NFAPΔh, and NFAPΔN after (b) heat-treatment at pH 7.0, (c) at different pH, and (d) in salt supplemented medium at pH 7.0. In all cases the untreated control cultures was referred to 100% growth. Significant differences (p-values) between the growth percentages were determined based on the comparison with the untreated control. When the growth percentages were compared in significance test, they are connected with line. ***p < 0.0001, **p < 0.005, *p < 0.05, ns: no significant difference. NFAP: recombinant Neosartorya fischeri NRRL 181 antifungal protein; NFAP∆h: hydrophobic core deletion NFAP mutant; NFAP∆N: N-terminal amino acids exchanged NFAP mutant.

NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN had no effects on hyphal morphology and physiology

Previously, we described that at sublethal concentrations NFAP affects the morphology of A. nidulans hyphae (hyperbranching and swollen hyphal tips, Supplementary Fig. S5a) as a consequence of disturbed actin distribution (Supplementary Fig. S5b) and chitin deposition (Supplementary Fig. S5c)8. Moreover, metabolic inactivation by NFAP was detected (Supplementary Fig. S5d)8. However, morphology (Supplementary Fig. S5a), actin distribution (Supplementary Fig. S5b), chitin deposition (Supplementary Fig. S5c) and metabolic activity (Supplementary Fig. S5c) of the A. nidulans hyphae were neither affected by NFAPΔh nor by NFAPΔN (Supplementary Fig. S5a–d).

Discussion

Following previous observations from other cysteine-rich, β-structured antimicrobial peptides and proteins17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24, folding, stability and antifungal activity of NFAP was proposed here to be dependent of the correct disulphide bond pattern, the presence of a hydrophobic core and the correct N-terminal amino acid sequence. Previously we demonstrated that P. pastoris KM71H is able to produce folded, antifungal active NFAP, and its antifungal efficacy is comparable to the native protein9. In the present study ECD spectroscopic measurements proved that this recombinant NFAP has the same structural elements, folding and thermal stability as the native protein (Fig. 3a,b). Thus, any differences in structure and activity of the NFAP mutants generated in this study, reflect the possible role of disulphide bonding, hydrophobic core and N-terminal amino acid sequence for the function of the native NFAP.

In silico homology modelling was employed to visualize potential structural disruption induced by amino acid exchanges in the respective motifs of NFAP. The modelling estimated the possible impact of amino acid exchanges on the overall solution structure of the protein. The models suggest that all NFAP mutants exhibit four β-strands instead of the five β-strands present in native NFAP and less disulphide bonds. This could be an indication of strong perturbation of the ordered secondary structure. The drastic structural rearrangements of the NFAP mutants in the in silico homology model strongly indicated that the affected structural elements could have a deep impact in the protein folding. However, one must be aware of the fact that this method cannot predict if a protein is unordered or not. Thus, the homology modelling was helpful to investigate the importance of structural elements in the folding, but no evidence for the overall solution structure of a protein is given. The ECD spectroscopy provided an experimental insight into this aspect.

A loss of ordered structure was indicated by ECD spectroscopic measurements of NFAP mutants, however, it has to be further investigated how the amino acid exchanges interfere with the overall three-dimensional solution structure of NFAP. Clearly, we plan to approach this objective in the near future by replacing further amino acids in NFAP and analysing the impact on its actual structure at atomic resolution by nuclear magnetic resonance.

In this study, however, we performed the first important steps towards a better understanding of the NFAP structure-function relation. We could show that the lack of disulphide bonds render NFAPΔC highly sensitive to proteolytic degradation (Supplementary Fig. S3, Supplementary Table S1). The presence of all disulphide bonds and formation of the correct disulphide bonding pattern proved to be also important for the structural integrity and antifungal activity of other, NFAP-related antifungal proteins, the Aspergillus giganteus AFP11 and P. chrysogenum PAF12, 16. Considering this last observation and that NFAPΔC was totally degraded during expression, we conclude that the presence of all disulphide bonds in the correct pattern is indispensable for stability and full antifungal activity.

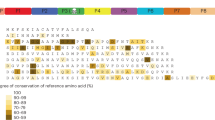

In this study, we observed for the first time that the hydrophobic core determines the folded and stable structure of NFAP. Substitution of neutral, hydrophobic amino acids (i.e. Y3, Y16, I18, Y23, Y44 at NFAP) to the neutral, hydrophilic serine in this region resulted in a mixture of differently truncated, unordered protein variants (NFAPΔh in Table 2 and Fig. 3a). Since neutral, hydrophobic amino acids are present at similar conserved positions in the primary structure of the so far isolated and characterized NFAP-related proteins (Supplementary Fig. S6), the universal role of the hydrophobic core in the proper protein folding of AFPs can be assumed. However, this hypothesis awaits further investigations.

NFAPΔN proved to be unstable (Table 2) and unordered (Fig. 3a) which indicates that the correct amino acid composition of the N-terminus of the mature protein is important for folding and stability. Information about the structural role of the first N-terminal amino acids of mature AFPs has not been reported so far; however, it was described that the antifungal activity of AFP is lost when it is not completely processed during fermentation and contains six additional amino acids at the N-terminus15. The role of the N-terminus in folding, stability and antimicrobial activity of defensins is also emphasised in the literature17, 23, 24.

The unordered NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN variants that lack amino acids at their N- and/or C-termini seemed to be more sensitive to extracellular protease degradation than NFAP. It is also possible that they could be differently processed during their maturation in the endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi complex and the extracellular space. However, further investigation needs to prove these assumptions.

The disulphide bond-stabilized, folded protein form is required for the antifungal activity of AFP11 and PAF16, hence we were curious about the antifungal activity of the unordered NFAPΔh, and NFAPΔN mutants in comparison with the folded NFAP. NFAPΔh proved to be inactive in all susceptibility tests (Fig. 4a–d), and NFAPΔN showed a reduction in antifungal activity. These results clearly indicate that the ordered, folded protein structure is also essential for the full antifungal activity of this AFP- and PAF-related protein (Fig. 4a). Heat treatment experiments with NFAP further evidenced the importance of the folded structure in the antifungal activity. After treatment at 50 °C NFAP showed the same antifungal activity as the sample which was not heated (Fig. 4b), and based on the ECD spectroscopic measurements NFAP is still intact and retains its folded structure at this temperature (Fig. 2b). In contrast, after heat treatment at 100 °C, the protein became unfolded (Fig. 3b) and lost its antifungal activity (Fig. 4b).

Heat-, pH-, and salt-tolerances of NFAP (Fig. 4b–d) observed in this study parallel well with our previously observed published data with Aspergillus niger 25 or A. nidulans 28. The thermal- and pH-sensitivity of NFAPΔN was similar to NFAP. However, NFAPΔN proved to be more sensitive to the ion strength of the medium (Fig. 4d), which might be possibly the reason of its reduced activity. Interestingly, NFAP∆N did not cause morphological or physiological changes on hyphae in contrast to NFAP, but slightly inhibited the fungal growth in a dose-independent manner. This needs further investigations. Other studies with plant defensins29 and the NFAP-related antifungal protein PAF from P. chrysogenum 30, 31 reported that specific protein motifs exhibit distinct antifungal features. Therefore, the observed functional differences of the NFAP mutants reflect the importance of the mutated motifs for full integrity and optimal antifungal action.

The in silico analysis of the structure, the folding dynamics and the antifungal properties of NFAP and its mutants provided a detailed insight into the role of the disulphide bonds, the hydrophobic core and the N-terminal amino acids of the mature protein for proper folding, stability and antifungal activity. The results presented in this study provide further evidences to the comprehensive understanding of the structure-function relationship of other members of the AFP group, considering their structural similarities. This is an important prerequisite for their rational design to develop new protein-based antifungal strategies in the near future.

Methods

In silico predictions and homology modelling

The molecular weight, pI, GRAVY value, total net charge, and disulphide bridge pattern of proteins were calculated and predicted by ExPASy ProtParam tool32, Protein Calculator v3.4 server (The Scripps Research Institute; http://www.scripps.edu/~cdputnam/protcalc.html), and DISULFIND Cysteines Disulfide Bonding State and Connectivity Predictor server33, respectively. The experimentally determined NFAP-related A. giganteus antifungal protein tertiary structure (Protein Data Bank (PDB) code: 1afp) served as a template to model the structure of NFAP. Putative tertiary structure of NFAP was predicted in silico by MODELLER 9.934, refined by ModRefiner35, and energy minimized and visualized with the UCSF Chimera software36. Residues in most favoured positions were validated by using the RAMPAGE server37. This in silico predicted tertiary structure of NFAP was used as a template to model the structure of NFAPΔC, NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN in the same way.

Cloning, transformation and protein preparation

NFAP, NFAPΔC, NFAPΔh and NFAPΔN encoding cDNA were synthetized by GenScript USA Inc. (Piscataway, NJ, USA) considering the preferential codon usage of P. pastoris. The synthetic genes carried the restriction site of XhoI and the Kex2 signal cleavage site (CTC GAG AAA AGA) at their 5′-end, and the restriction site of XbaI (TCT AGA) at their 3′-end. They were cloned into XhoI-XbaI digested pPICZαA expression vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and these constructs were used to transform P. pastoris KM71H (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) cells as previously described9. Heterologous protein expression in P. pastoris KM71H for four days and protein purification were performed on a CM-Sepharose column as reported9.

Identification of produced proteins

Purified proteins were identified based on their molecular mass at the Protein Micro-Analysis Facility of Biocenter at Medical University of Innsbruck (Innsbruck, Austria). The protein samples were ZipTip enriched (EMD; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), dissolved in 100 mM acetic acid and analysed (180 nl/min flow rate) with capillary electrophoresis (CE)-ESI-MS (20 kV separation voltage, 10 psi pressure) on a CESI 8000 (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA) coupled to a Q Exactive (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Protein masses were determined by deconvolution using the integrated Xcalibur pXtract software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

The expression of NFAPΔC was verified by the identification of different peptide fragments from the degraded product. The NFAPΔC supernatant was separated into four different molecular weight fractions (>10 kDa, <10 kDa, 3–10 kDa and <3 kDa) by centrifugal ultrafiltration (Vivaspin 500 10,000 MWCO PES then 3,000 MWCO PES; Sartorius Stedim Biotech GmbH, Gottingen, Germany), before a mass spectrometric method was used to identify peptide fragments derived from NFAPΔC. This method was based on enzymatic digestion of the proteins present in each fraction and peptide mass mapping (Protein Prospector, MS-fit http://prospector.ucsf.edu/). For in solution protein digestion, 10 μl of protein solution containing 1 μg/μl protein was mixed with a buffer containing 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0. The protein was subjected to enzymatic cleavage with 0.1 μg trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) solution (in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate) overnight at 37 °C. Digested samples were analysed on a Waters NanoAcquity UPLC (Waters MS Technologies, Manchester, UK) system coupled with a Q Exactive Quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). LC conditions were the followings: flow rate: 350 nl/min; eluent A: water with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid, eluent B: acetonitrile with 0.1%(v/v) formic acid; gradient: 40 min, 3–40% (v/v) B eluent; column: Waters BEH130 C18 75 lm/250 mm column with 1.7 μm particle size C18 packing (Waters Inc., Milford, MA, USA). Based on our previous experiences with the filtration of cysteine-rich and cationic antifungal proteins (and possibly their degradation products) showing high-affinity for the filter membrane material occlusion of the pores can occur, which inhibits the filtration of the proteins and bigger peptide fragments. Hence, the >10 kDa fraction was also analysed, although the molecular weights of the NFAPΔC peptides fragments were expected to be much below this cut-off.

Investigation of structural alterations

Structural alterations of NFAP and its mutants were examined by RP-HPLC, using an Agilent 1100 Series liquid chromatograph (Agilent technologies, Little Falls, DE, USA) and a Phenomenex Jupiter C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm; 10 μm particle size; 300 Å pore size; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). Linear gradient elution was carried out with 0.1% TFA in water (eluent A) and 80% acetonitrile and 0.1% TFA is water (eluent B) from 15% to 40% (B) over 25 min at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min.

Electronic circular dichroism spectroscopy

Electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectroscopic measurements of NFAP and the mixtures of unordered NFAPΔh, and NFAPΔN variants were performed in the 185–260 nm wavelength range using a Jasco-J815 spectropolarimeter (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). Protein samples were presented in pure water at 0.1 mg/ml concentration and spectra were collected at 25 °C with a scan speed of 100 nm/s using a 0.1 cm pathlength quartz cuvette. The reported spectra are accumulations of 10 scans, from which the spectrum of pure water was subtracted. Acquisition of thermal unfolding curves of proteins was done by recording ellipticity as a function of temperature at 228 nm. The temperature was increased from 25 °C up to 95 °C in 5 °C increments, at a rate of 1 °C/min using a Peltier thermoelectronic controller (TE Technology, Traverse City, MI, USA). Measurements of ellipticities were taken at each temperature point after allowing the system to equilibrate for 1 min. Ellipticity data were corrected for protein concentration, which was determined based on the UV absorbance of aromatic and cysteine residues, following the protocol published by Greenfield, N. J.38 Secondary structural contributions were determined by the CDSSTR method from the ECD spectra of native and recombinant NFAP measured at 25 °C39.

In vitro antifungal susceptibility tests

In vitro susceptibility tests were performed in a 96-well microtiter plate bioassay in the presence of increasing amount of proteins (2.5–40 μg) in SPEC medium at pH 7.025 against the NFAP-sensitive model fungus A. nidulans strain FGSC A4 (Fungal Genetics Stock Center, Kansas, MO, USA) as described8. To investigate the salt, pH, and temperature sensitivity of the proteins (20 μg) the medium was supplemented with NaCl or MgSO4 (25–100 mM), or it was prepared in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.0–8.0), or exposed to different temperatures (25, 50, 100 °C) for 30 min. The flat-bottom plates were incubated for 48 hours at 37 °C without shaking, then after shaking for five seconds, the absorbance (OD620) were measured in well scanning mode with a microtiter plate reader (FLUOstar Omega, BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany). Respective fresh media were used for background calibration. For calculation of the growth ability in presence of NFAP and the mixtures of unordered NFAPΔh, and NFAPΔN variants, the absorbance of the untreated control cultures (media without NFAP or its mutants) were referred to 100% growth. Susceptibility tests were prepared in triplicates and repeated three times.

Investigation of the antifungal mechanism

The effect of NFAP and its mutants on the metabolic activity, actin distribution, and chitin content of A. nidulans FGSC A4 and A. nidulans GR540 strains was investigated by means of 30 minutes-long exposure to sublethal protein concentrations (25 μg/ml) as described previously8.

Microscopy

Cells were visualized by light and fluorescence microscopy (Carl Zeiss Axiolab LR 66238C; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and photographed by a microscope camera (Zeiss AxioCam ERc 5s; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2010 software (Microsoft, Edmond, WA, USA) or GraphPad Prism version 5.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Two sample t-test or one-way ANOVA analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison posttest was used.

References

Meyer, V. et al. Current challenges of research on filamentous fungi in relation to human welfare and a sustainable bio-economy: a white paper. Fung. Biol. Biotechnol. 3, 6, doi:10.1186/s40694-016-0024-8 (2016).

Meyer, V. A small protein that fights fungi: AFP as a new promising antifungal agent of biotechnological value. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 78, 17–28, doi:10.1007/s00253-007-1291-3 (2008).

Marx, F., Binder, U., Leiter, E. & Pócsi, I. The Penicillium chrysogenum antifungal protein PAF, a promising tool for the development of new antifungal therapies and fungal cell biology studies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 445–454, doi:10.1007/s00018-007-7364-8 (2008).

Barakat, H., Stahl, U. & El-Mansy, H. Application for the antifungal protein from Aspergillus giganteus: Use with selected foodstuffs as regards to quality and safety. (ed. Müller, V.) (VDM Verlag Dr. Müller 2010).

Delgado, J., Owens, R. A., Doyle, S., Asensio, M. A. & Núñez, F. Manuscript title: antifungal proteins from moulds: analytical tools and potential application to dry-ripened foods. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 6991–7000, doi:10.1007/s00253-016-7706-2 (2016).

Galgóczy, L., Kovács, L. & Vágvölgyi, C. Defensin-like antifungal proteins secreted by filamentous fungi in Current Research, Technology and Education Topics in Applied Microbiology and Microbial Biotechnology Vol. 1, Microbiology Book Series-Number 2 (ed. Méndez-Vilas, A.) 550–559 (Formatex 2010).

Hegedus, N. et al. The small molecular mass antifungal protein of Penicillium chrysogenum–a mechanism of action oriented review. J. Basic. Microbiol. 51, 561–571, doi:10.1002/jobm.v51.6 (2011).

Virágh, M. et al. Insight into the antifungal mechanism of Neosartorya fischeri antifungal protein. Protein Cell 6, 518–528, doi:10.1007/s13238-015-0167-z (2015).

Virágh, M. et al. Production of a defensin-like antifungal protein NFAP from Neosartorya fischeri in Pichia pastoris and its antifungal activity against filamentous fungal isolates from human infections. Protein Expr. Purif. 94, 79–84, doi:10.1016/j.pep.2013.11.003 (2014).

Campos-Olivas, R. et al. NMR solution structure of the antifungal protein from Aspergillus giganteus: evidence for cysteine pairing isomerism. Biochemistry 34, 3009–3021, doi:10.1021/bi00009a032 (1995).

Lacadena, J. et al. Characterization of the antifungal protein secreted by the mould Aspergillus giganteus. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 324, 273–281, doi:10.1006/abbi.1995.0040 (1995).

Batta, G. et al. Functional aspects of the solution structure and dynamics of PAF-a highly-stable antifungal protein from Penicillium chrysogenum. FEBS J. 276, 2875–2890, doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07011.x (2009).

Seibold, M., Wolschann, P., Bodevin, S. & Olsen, O. Properties of the bubble protein, a defensin and an abundant component of a fungal exudate. Peptides 32, 1989–1995, doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2011.08.022 (2011).

Fizil, Á., Gáspári, Z., Barna, T., Marx, F. & Batta, G. “Invisible” conformers of an antifungal disulfide protein revealed by constrained cold and heat unfolding, CEST-NMR experiments, and molecular dynamics calculations. Chemistry 23, 5136–5144, doi:10.1002/chem.201404879 (2015).

Martínez-Ruiz, A. et al. Characterization of a natural larger form of the antifungal protein (AFP) from Aspergillus giganteus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1340, 81–87, doi:10.1016/S0167-4838(97)00038-1 (1997).

Váradi, G. et al. Synthesis of PAF, an antifungal protein from P. chrysogenum, by native chemical ligation: native disulfide pattern and fold obtained upon oxidative refolding. Chemistry 19, 12684–12692, doi:10.1002/chem.201301098 (2013).

Taylor, K., Barran, P. E. & Dorin, J. R. Structure-activity relationships in beta-defensin peptides. J. Pept. Sci. 90, 1–7, doi:10.1002/bip.20900 (2008).

Scudiero, O. et al. Novel synthetic, salt-resistant analogs of human beta-defensins 1 and 3 endowed with enhanced antimicrobial activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 2312–2322, doi:10.1128/AAC.01550-09 (2010).

Munson, M. et al. What makes a protein a protein? Hydrophobic core designs that specify stability and structural properties. Protein Sci. 5, 1584–1593, doi:10.1002/pro.v5:8 (1996).

Cheung, M. S., García, A. E. & Onuchic, J. N. Protein folding mediated by solvation: water expulsion and formation of the hydrophobic core occur after the structural collapse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 685–690, doi:10.1073/pnas.022387699 (2002).

Camilloni, C. et al. Towards a structural biology of the hydrophobic effect in protein folding. Sci. Rep. 6, 28285, doi:10.1038/srep28285 (2016).

Carter, C. W. Jr., LeFebvre, B. C., Cammer, S. A., Tropsha, A. & Edgell, M. H. Four-body potentials reveal protein-specific correlations to stability changes caused by hydrophobic core mutations. J. Mol. Biol. 311, 625–638, doi:10.1006/jmbi.2001.4906 (2001).

Sahl, H. G. et al. Mammalian defensins: structures and mechanism of antibiotic activity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 77, 466–475, doi:10.1189/jlb.0804452 (2005).

Klüver, E., Adermann, K. & Schulz, A. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship of beta-defensins, multi-functional peptides of the immune system. J. Pept. Sci. 12, 243–257, doi:10.1002/psc.749 (2006).

Kovács, L. et al. Isolation and characterization of Neosartorya fischeri antifungal protein (NFAP). Peptides 32, 1724–1731, doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2011.06.022 (2011).

Bhattacharyya, R., Pal, D. & Chakrabarti, P. Disulfide bonds, their stereospecific environment and conservation in protein structures. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 17, 795–808, doi:10.1093/protein/gzh093 (2004).

Lees, J. G., Miles, A. J., Wien, F. & Wallace, B. A. A reference database for circular dichroism spectroscopy covering fold and secondary structure space. Bioinformatics 22, 1955–1962, doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl327 (2006).

Galgóczy, L. et al. Investigation of the antimicrobial effect of Neosartorya fischeri antifungal protein (NFAP) after heterologous expression in Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiology 159, 411–419, doi:10.1099/mic.0.061119-0 (2013).

Muñoz, A. et al. Specific domains of plant defensins differentially disrupt colony initiation, cell fusion and calcium homeostasis in Neurospora crassa. Mol Microbiol. 92, 1357–1374, doi:10.1111/mmi.12634 (2014).

Sonderegger, C. et al. A Penicillium chrysogenum-based expression system for the production of small, cysteine-rich antifungal proteins for structural and functional analyses. Microb Cell Fact. 15, 192, doi:10.1186/s12934-016-0586-4 (2016).

Sonderegger, C. et al. D19S Mutation of the cationic, cysteine-rich protein PAF: Novel insights into its structural dynamics, thermal unfolding and antifungal function. PLoS One 12, e0169920, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169920 (2017).

Gasteiger, E. et al. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server in The proteomics protocols handbook (ed. Walker, J. M.) 571–607 (Humana Press 2005).

Ceroni, A., Passerini, A., Vullo, A. & Frasconi, P. DISULFIND: a disulfide bonding state and cysteine connectivity prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W177–W181, doi:10.1093/nar/gkl266 (2006).

Sali, A., Potterton, L., Yuan, F., van Vlijmen, H. & Karplus, M. Evaluation of comparative protein modelling by MODELLER. Proteins 23, 318–326, doi:10.1002/prot.340230306 (1995).

Xu, D. & Zhang, Y. Improving the physical realism and structural accuracy of protein models by a two-step atomic-level energy minimization. Biophys J 101, 2525–2534, doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.024 (2011).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612, doi:10.1002/jcc.20084 (2004).

Lovell, S. C. et al. Structure validation by Calpha geometry: phi,psi and Cbeta deviation. Proteins 50, 437–450, doi:10.1002/prot.10286 (2003).

Greenfield, N. J. Using circular dichroism spectra to estimate protein secondary structure. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2876–2890, doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.202 (2006).

Sreerama, N. & Woody, R. W. Estimation of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectra: comparison of CONTIN, SELCON, and CDSSTR methods with an expanded reference set. Anal. Biochem. 287, 252–260, doi:10.1006/abio.2000.4880 (2000).

Taheri-Talesh, N. et al. The tip growth apparatus of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 1439–1449, doi:10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0464 (2008).

Acknowledgements

L.G. holds a Lise Meitner fellowship from Austrian Science Fund (FWF): M1776-B20. Research of A.B. has been supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The authors would like to thank Zoltán Gáspári (Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Information Technology & Bionics, Budapest, Hungary) for advices in the homology modelling, and Doris Bratschun-Khan (Medical University of Innsbruck, Biocenter, Division of Molecular Biology, Innsbruck, Austria) for technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.G. and F.M. conceived and supervised the study, designed experiments, and edited the manuscript; L.G. and M.V. performed in silico predictions and homology modelling; L.G. performed cloning, transformation and protein preparation, in vitro antifungal susceptibility tests and analysis of related data; A.B. performed ECD spectroscopy and analysis of related data; M.V. and H.F. performed investigation of the antifungal mechanism and the related microscopy; G.V. and Z.K. performed RP-HPLC analysis, identification of degraded proteins by mass spectrometry and analysis of related data; L.G., A.B., G.V., Z.K. and F.M. wrote the manuscript; L.G., A.B., Z.K., G.V. and F.M. made manuscript revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Galgóczy, L., Borics, A., Virágh, M. et al. Structural determinants of Neosartorya fischeri antifungal protein (NFAP) for folding, stability and antifungal activity. Sci Rep 7, 1963 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02234-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02234-w

This article is cited by

-

Homology Modeling and Analysis of Vacuolar Aspartyl Protease from a Novel Yeast Expression Host Meyerozyma guilliermondii Strain SO

Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering (2023)

-

New Antimicrobial Potential and Structural Properties of PAFB: A Cationic, Cysteine-Rich Protein from Penicillium chrysogenum Q176

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Efficient production and characterization of the novel and highly active antifungal protein AfpB from Penicillium digitatum

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.