Abstract

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) are activators of innate and adaptive immune responses that express HLA-DR, toll-like receptor (TLR) 7, TLR9 and produce type I interferons. The role of human pDC in malaria remains poorly characterised. pDC activation and cytokine production were assessed in 59 malaria-naive volunteers during experimental infection with 150 or 1,800 P. falciparum-parasitized red blood cells. Using RNA sequencing, longitudinal changes in pDC gene expression were examined in five adults before and at peak-infection. pDC responsiveness to TLR7 and TLR9 stimulation was assessed in-vitro. Circulating pDC remained transcriptionally stable with gene expression altered for 8 genes (FDR < 0.07). There was no upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules CD86, CD80, CD40, and reduced surface expression of HLA-DR and CD123 (IL-3R-α). pDC loss from the circulation was associated with active caspase-3, suggesting pDC apoptosis during primary infection. pDC remained responsive to TLR stimulation, producing IFN-α and upregulating HLA-DR, CD86, CD123 at peak-infection. In clinical malaria, pDC retained HLA-DR but reduced CD123 expression compared to convalescence. These data demonstrate pDC retain function during a first blood-stage P. falciparum exposure despite sub-microscopic parasitaemia downregulating HLA-DR. The lack of evident pDC activation in both early infection and malaria suggests little response of circulating pDC to infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Innate recognition of Plasmodium parasites is critical for the induction of appropriate anti-malarial immune responses1. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) are important mediators of both innate and adaptive immune responses (reviewed in ref. 2). Human pDC are HLA-DR+ blood cells that lack the lineage-associated markers CD3, CD19, CD14, CD56, CD11c and express high levels of the IL-3 receptor alpha chain CD123. Unlike myeloid DC, pDC express toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 and TLR9 thereby allowing recognition of single-stranded RNA3 and DNA4, 5, respectively. Upon recognition of pathogen nucleic acids, pDC produce large amounts of immune regulatory type I interferons (IFNs). pDC MHC class I and II molecules allow pDC antigen-presentation to CD8+ T cells (cross-presentation)6 and CD4+ T cells7. In addition, pDC regulate the generation of plasma cells and antibody responses8, 9.

The role of pDC in Plasmodium infection remains unclear. Plasmodium parasite protein-DNA complexes are thought to activate TLR910, 11, and Plasmodium-derived RNA can trigger type I IFN responses in a TLR7-dependent12 and -independent fashion13 in mice. The Plasmodium agonist of human TLR7 remains to be identified.

Murine models of malaria show differing pDC responses, depending on the mouse strain and parasite species. Across mouse strains, pDC upregulate CD8612, 14, 15, MHC class II14 or CD4012 following Plasmodium infection. Production of type I IFN by pDC has been demonstrated at the transcriptional14, 16 and protein level15, 17 following infection with three rodent-infecting Plasmodium species. The relevance of pDC activation in murine malaria is debated. In the P. chabaudi model of chronic infection and the P. berghei model of cerebral malaria, pDC are considered not relevant for the control of blood parasitaemia or disease outcome despite their activation12, 14, 16. Most recently, pDC derived type I IFN early during infection has been reported as essential for the induction of protective immune responses against lethal P. yoelii YM17, and Plasmodium parasites may prevent early pDC type-I IFN release by activating cross-regulatory type-I IFN pathways17.

Much less is known about the role of pDC in human malaria, mainly due to limitations intrinsic to human studies and restrictions to peripheral blood. There is a consensus that blood pDC numbers decline in acute clinical malaria18,19,20,21,22. However, it is unclear whether pDC loss is due to migration18 or cell death19. Evaluation of pDC maturation in malaria has been limited to the assessment of surface CD86 and HLA-DR. CD86 upregulation has been reported in children with severe malaria15, P. falciparum infected pregnant women20 and some patients with acute vivax malaria23, whilst HLA-DR is not upregulated in severe malaria15, 24. In agreement with this, a Malian study of two ethnic groups with differing susceptibility to symptomatic malaria shows in P. falciparum infected malaria-susceptible Dogon, pDC downregulate HLA-DR expression, lack upregulation of CD86 and show impaired responsiveness to TLR9 stimulation. Circulating pDC in P. falciparum infected Fulani, an ethnic group less susceptible to symptomatic malaria, on the contrary, display a mature phenotype with upregulated CD86 and HLA-DR expression and strong TLR9 responsiveness25. These studies, together with recent murine studies15, 17, suggest that pDC may play an integral part in the acquisition of clinical immunity.

Surprisingly, our recent report on early P. falciparum blood-stage infection found pDC to be minor contributors to the early IFN-α response26. We have also shown, circulating pDC decline early during the pre-patent phase of a primary infection27. These findings, together with the recent report of inhibited type I IFN release from pDC during early P. yoelii infection17 and our past identification of profoundly impaired CD1c+ myeloid DC in very early P. falciparum infection28, prompted us to investigate pDC activation and function in more detail. Controlled human malaria infection (CHMI), provides the unique ability to assess host responses during P. falciparum blood-stage infection with each individual’s baseline response before infection. To characterise pDC activation and function in a primary P. falciparum blood-stage infection, we isolated highly purified pDC for gene expression analysis, monitored the expression of co-stimulatory markers CD86, CD80 and CD40 and measured pDC responsiveness to TLR7 and TLR9 stimulation at baseline and at peak-infection.

Results

Circulating pDC gene expression is predominantly stable after primary pre-patent P. falciparum CHMI

We isolated blood pDC at >98% purity from five volunteers at baseline and at peak parasitaemia following intravenous infection with 1,800 pRBC (n = 5, median parasitaemia 4,754/mL [1,320–11,929]). Transcriptional gene expression changes were investigated by RNA sequencing as described in the methods. Globally, there were only modest changes (false detection rate, FDR < 0.07) in pDC gene expression. Eight gene transcripts had significantly decreased or increased gene expression (FDR < 0.07, Supplementary Figure 1), when baseline was compared to peak-infection. A summary of the top 10 genes that increased and top ten genes that decreased expression at peak-infection is presented in Table 1. No P. falciparum RNA signal was detected (data not shown).

Circulating pDC of immature phenotype during early P. falciparum CHMI

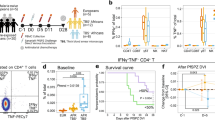

To phenotypically characterise pDC during early P. falciparum infection we assessed maturation markers; CD86, CD40, CD80, HLA-A,B,C, HLA-DR and CD123 (IL-3Rα) expression on pDC before and at peak-infection for participants infected with either 150 pRBC or 1,800 pRBC. Mean parasitaemia was determined by PCR29. Participants administered 150 pRBCs reached peak parasitaemia on day 10 (n = 1, parasitaemia 12,750/mL), or day 11 (n = 11, median parasitaemia 2,380/mL [IQR 696–5085]), whereas participants administered 1,800 pRBCs reached peak parasitaemia on day 7 (n = 23, median parasitaemia 6,877/mL [IQR 4,759–12,813]) or day 8 (n = 24, median parasitaemia 4,970/mL [IQR 666–18,065]) (Fig. 1A). Circulating pDC were identified in whole blood as lineage marker negative (CD3, CD14, CD19, CD20, CD34 and CD56), HLA-DR+, CD11c− and CD123+ (Fig. 1B). In fresh whole blood, less than 1% of pDC expressed CD86, CD40 or CD80 before infection or at peak parasitaemia (Fig. 1C). pDC expression of CD123, the alpha subunit to the IL-3 receptor (IL-3Rα)30, frequently used to identify pDC subsets31, significantly reduced at peak parasitaemia and failed to recover by 24 hours after antimalarial treatment (Fig. 1D,E). HLA-DR expression on pDC also reduced in both cohorts at peak parasitaemia (Fig. 1D,E). Additionally, HLA-A,B,C expression increased on pDC in the 1,800 pRBC cohort, although the increase was not statistically significant (Fig. 1E). In accordance with previous reports32, 33, pDC did not uptake FITC-dextran particulate antigen at baseline and this did not change with infection (data not shown). In clinical malaria, circulating pDC showed a similarly immature phenotype lacking upregulation of CD86 or HLA-DR and significantly reduced CD123 expression during acute disease compared to convalescence (Fig. 2).

Circulating pDC are not activated in P. falciparum CHMI. (A) Schematic of clinical trial cohorts 150 pRBC (black) and 1,800 pRBC (grey), arrows indicate antimalarial treatment. (B) Fresh whole blood gating strategy for pDC. pDC were identified as negative for lineage markers (CD3, CD14, CD19, CD20, CD34 and CD56), HLA-DR+ (2nd panel), CD11c− and CD123+ (3rd panel). (C) Representative flow cytometry plots from one participant showing CD86, CD40 and CD80 pDC expression before infection (day 0) and at peak-infection. Gated on total DC as shown in Fig. 1B 2nd panel. (D) Longitudinal pDC CD123 and HLA-DR expression after 150 pRBC infection. (E) Longitudinal pDC CD123, HLA-DR and HLA-A,B,C expression after 1,800 pRBC infection. Box plots show the minimum, maximum, median and interquartile range for data from all participants (turkey plot). Abbreviations FSC, forward scatter, SSC, side scatter, MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

Characterisation of circulating pDC in clinical patients infected with P. falciparum. (A) The absolute number of circulating pDC in 5 healthy controls (black triangles) and 10 patients with acute P. falciparum and at convalescence, 14 to 28 days after antimalarial drug treatment (Post Rx). (B) Longitudinal HLA-DR expression (MFI) on pDC of patients with acute P. falciparum malaria. (C) Longitudinal CD86 percent positive pDC of patients with acute P. falciparum malaria. (D) Longitudinal CD123 expression (MFI) on pDC of patients with acute P. falciparum malaria. Mann-Whitney t-test was used for comparison between healthy controls and clinical malaria patients. Wilcoxon matched-paired test was used for comparison between acute malaria and convalescence (Post Rx). Abbreviations: MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

Reduced circulating pDC number is associated with increased active caspase-3 expression

Circulating pDC numbers were determined longitudinally in both the 1,800 pRBC and 150 pRBC infection cohorts. pDC significantly declined at peak parasitaemia and continued to fall 24 hours after antimalarial drug treatment in the 1,800 pRBC infection cohort (Fig. 3A , grey bars). In the lower 150 pRBC cohort, pDC number fell significantly 24 hours pre and post peak parasitaemia (Fig. 3A , white bars). After antimalarial drug treatment, pDC numbers remained low at 48 and 72 hours (Fig. 3A). To determine if the loss of pDC was attributable to an increase in pDC apoptosis, circulating pDC were examined for the presence of the active form of caspase-3, a hallmark apoptosis marker. Caspase-3 is an executioner caspase, essential to both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways34. There was no evidence of active caspase-3 in blood pDC following infection with 150 pRBC (n = 6; median 1% [IQR 1–3%] caspase-3, Fig. 3B). In contrast, following 1,800 pRBC infection, we observed significantly increased active caspase-3 in pDC (n = 30; median 6.5% [IQR 2–18] caspase-3, Fig. 3B ). Longitudinal changes in circulating pDC number and active caspase-3 expression were assessed in the 1,800 pRBC cohort, 48 hours before peak parasitaemia (day 6) to 48 hours after antimalarial treatment (day 10). As P. falciparum infection progressed, the number of circulating pDC declined, while pDC expressing caspase-3 increased (Fig. 1C). Thus, we show for the first time that pDC are apoptotic during the higher dose P. falciparum infection.

Increased pDC active caspase-3 detection. (A) The absolute number of circulating pDC after 1,800 pRBC infection; arrows indicate day of antimalarial treatment (n = 9 (day 7), n = 24 (day 8)). The absolute number of circulating pDC after 150 pRBC infection; arrows indicate day of antimalarial treatment (n = 1 (day 10), n = 11 (day 11)). Box plots show the minimum, maximum, median and interquartile range for data from all participants (turkey plot). Data points outside of box plots represent patients which were outliers. The number of individual data points for each day is given below the x-axis. (B) Percentage of pDC positive for active caspase-3 after 150 pRBC (n = 6, open circles) or 1,800 pRBC (n = 30, closed circles) infection. The horizontal line and whiskers represent the median and inter-quartile range, Wilcoxon matched-paired test was used for comparison between day 0 and day 7–8 (peak) or day 10–11 (peak). (C) Mean (+/−SEM) number of circulating pDC (white squares) and proportion of active caspase-3 positive pDC (black circles) after 1,800 pRBC infection n = 30. Abbreviations: FSC, forward scatter SSC, side scatter, MFI, median fluorescence intensity, SEM, standard error of the mean.

Circulating pDC retain the ability to produce IFN-α and TNF during controlled P. falciparum infection

To assess pDC function during early P. falciparum infection we evaluated IFN-α, TNF, IL-10 and IL-12 cytokine production and maturation in response to TLR stimulation (n = 8, Fig. 4A). pDC were identified as lineage−, HLA-DR+, CD11c− and CD123 (IL-3Rα)+ (Fig. 4A). At peak-infection, more pDC produced IFN-α in response to TLR7 (p = 0.02, Fig. 4B) or TLR9 stimulation (p = 0.08, Fig. 4C), when compared to baseline hence, the ability of pDC to produce IFN-α was not diminished during early P. falciparum blood-stage infection. IFN-α producing pDC always co-produced TNF (Fig. 4A) and infection did not change the proportion of pDC producing TNF alone (Fig. 4B,C). A comparison between cytokine MFI at peak parasitaemia and baseline (day 0) showed that TLR9-stimulated pDC expressed more IFN-α at peak-infection (Fig. 4D), whilst TNF production remained unchanged (Fig. 4E). No IL-10 or IL-12 production by pDC was detected. The same pattern of cytokine response (dual IFN-α/TNF and no IL-12 or IL-10) was observed when PBMC or fresh whole blood was used in the assay.

pDC cytokine responses to TLR stimulation. (A) Representative staining of circulating pDC in PBMC evaluated for intracellular cytokines. pDC were identified as lineage (CD14, CD3, CD19 and CD56)−, HLA-DR+, CD11c− and CD123+. Intracellular cytokine production by ex vivo pDC on day 0 (IFN-α and TNF) in three conditions: no stimulation (top panel), TLR7 stimulation (middle panel) and TLR9 stimulation (bottom panel). (B) IFN-α and TNF produced by pDC on day 0 and day 7 after TLR7 stimulation, n = 8. (C) IFN-α and TNF produced by pDC on day 0 and day 7 after TLR9 stimulation, n = 8. (D) IFN-α MFI of IFN-α producing pDC after TLR7 or TLR9 stimulation, n = 8. (E) TNF MFI of TNF producing pDC after TLR7 or TLR9 stimulation, n = 8. Data are represented as median and interquartile range. The Wilcoxon matched-paired test was used for comparison between day 0 and day 7. Abbreviations: FSC, forward scatter SSC, side scatter, MFI, median fluorescence intensity.

Circulating pDC significantly increased HLA-DR and CD123 surface expression upon TLR7 or TLR9 stimulation, at both baseline and peak parasitaemia (n = 8, Fig. 5A,B). CD86 expression increased significantly following TLR7 stimulation at both baseline and peak parasitaemia, but not upon TLR9 stimulation with CpGA (Fig. 5C), as previously reported35. There was no significant change in pDC HLA-DR, CD86 or CD123 expression, either without stimulation (NIL) or following TLR7 or TLR9 stimulation, when baseline was compared to peak-infection in eight individuals.

Increased HLA-DR, CD123 and CD86 expression on pDC upon TLR stimulation. (A) pDC HLA-DR expression (B) pDC CD123 expression and (C) pDC CD86 percent gated on day 0 or day 7, in three conditions: no stimulation and after TLR7 or TLR9 stimulation, n = 8. Box plots show the minimum, maximum, median and interquartile range for data. Multiple comparisons test (1-way ANOVA) was used for comparison between no stimulation and TLR stimulation.

Discussion

Here, we have shown pDC are not activated and remain functional during early P. falciparum infection. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to sequence RNA from highly purified pDC and compare gene expression before and at the peak of a primary P. falciparum CHMI. Unexpectedly, we found pDC gene expression to be largely stable in early sub-microscope infection. The observed minimal change in gene expression, together with an absence of activation/maturation phenotype by flow cytometry suggests, circulating blood pDC are not activated, yet remain functional during pre-patent blood-stage infection.

While pDC gene expression was largely unchanged during early infection, a panel of eight genes significantly increased or decreased at peak-infection. The greatest increase in gene expression was seen in NLRC5 (NOD-like receptor (NLR) family, caspase recruitment (CARD) domain containing 5), an IFNγ-inducible transcriptional coactivator of MHC class I gene expression also known as CITA (MHC class I transactivator)36. NLRC5 is the master regulator of MHC class I gene expression and activates most of the key components of the MHC class I antigen presentation pathway37. In line with this, non-classical MHC class I HLA-F was in the top 10 upregulated genes in this study, although with a FDR > 0.07. Increased HLA class I protein expression was detected on the day after treatment, although not statistically significant. Together these findings suggest that pDC upregulate their MHC class I antigen presentation machinery during early P. falciparum infection, whether this leads to cross-presentation of parasite antigen to activate CD8+ T cells38 or makes them targets for elimination by cytotoxic CD8+ T cells remains unclear. pDC have been suggested to act as a reservoir for Plasmodium in mice39; however, we detected no Plasmodium RNA in isolated pDC to support this previous finding, suggesting that this does not occur in human pDC or that our methods lacked the sensitivity to identify Plasmodium RNA. Although still controversial, NLRC5 has also been reported to modulate type I IFN responses in various human and murine cell types40. Future studies into the effects of NLRC5 in malaria are warranted.

Amongst the downregulated genes was BAG3 (BCL2 associated athanogene gene 3), an anti-apoptotic co-chaperone protein41. Down-modulation of BAG3 in HIV-infected microglial cells results in accumulation of active caspase-342. Here we show active caspase-3 detection by flow cytometry in pDC increased in the 1,800 pRBC cohort during early P. falciparum infection and was associated with pDC loss from the circulation. pDC loss equally occurred in the 150 pRBC cohort yet, this did not coincide with active caspase-3 detection. Whether this apparent lack of apoptosis in the 150 pRBC cohort is due to differing parasitaemia on the day of treatment or to the longer exposure to a very low parasite dose remains unclear. Very low doses of P. falciparum blood-stages have previously been shown to induce host immunity43. The reduction in blood pDC numbers during Plasmodium infection is in accordance with previous reports18,19,20,21,22,23, 27. Additionally, we show for the first time, pDC reduce CD123, IL-3α receptor expression in P. falciparum CHMI and in acute falciparum malaria, suggesting this effect is independent of the route of infection. Whether this reduction impacts responsiveness to IL-3, a T cell derived glycoprotein that supports the viability and differentiation of haematopoietic cells44 remains to be determined. Studies of isolated pDC from healthy adults report an increase in pDC CCR7 expression after in vitro stimulation with high concentration of P. falciparum schizont antigen18, suggesting pDC increase their ability to migrate to lymphoid organs following parasite contact. Whilst we did not detect any changes in CCR7 gene expression in this early infection, gene expression of CXCR4 was downregulated. pDC constitutively express CXCR4 on their surface which is required for their development45 but also allows them to enter lymphoid tissues via high endothelial venules46. Downregulation of CXCR4 transcription may indicate less repopulation from the bone marrow, reduced ability to migrate to lymphoid tissue or indeed very early activation, as pDC downregulate CXCR4 gene expression following in vitro stimulation with Influenza virus47. In the P. yoelii model of severe malaria, pDC activation occurs very early during blood-stage infection15, 17 and activated type I IFN producing pDC reside predominantly in the bone marrow and blood of P. yoelii YM infected mice15 and not in the spleen as previously suggested14, 48. Conclusive evaluation of dendritic cell migration in human malaria will need to be addressed by researchers with access to Plasmodium infected human spleen tissue.

Blood pDC are important for maintaining a balance between immunity and immunopathology in viral infections2. Early production of type I IFNs by pDC are needed for containment of virues in systemic infections such as HSV-149. However, pDC derived type I IFNs become less important later on in the infection, as other host cell responses become more dominent (reviewed in ref. 2). Moreover, pDC may contribute to the chronicty of HIV infection through dysregulated activation and type I IFN production50. The beneficial or detrimental effects of pDC and type I IFNs in infection may depend on the timing of their action. In lethal P. yoelii YM infection, early type I IFN production during infection is essential for the induction of protective immune responses17. In contrast, type I IFN production in P. berghei ANKA infection, leads to suppression of CD4+ T cell adaptive immune responses51, although the cellular sources of IFN-α were not identified. Whether pDC activation is desirable or detrimental in human malaria is still not clear.

Assessment of rare human dendritic cell subsets is difficult, and accessing longitudinal human malaria samples is even more challenging. To gain insights into human pDC function in malaria, we took advantage of the CHMI, which allowed longitudinal assessment of pDC function in malaira naive volunteers. Despite loss and apparent apoptosis, pDC retained the ability to respond to TLR stimulation. In contrast, during this same time frame of early pre-patent P. falciparum infection peripheral blood CD1c+ mDC are dysfunctional and unable to upregulate HLA-DR following TLR stimulation28. Together, our studies suggest that DC subsets are differentially affected during P. falciparum blood-stage infection and these differences should be considered when evaluating dendritic cells in Plasmodium infection and malaria. Evidence of a functional human dendritic cell subset in P. falciparum infection is encouraging, as pDC may orchestrate downstream adaptive immune responses during infection.

Methods

P. falciparum CHMI

Written and informed consent was obtained from 59 volunteers who participated in a series of phase Ib clinical trials testing the efficacy of antimalarial drugs. Blood-stage P. falciparum infection was initiated by inoculation of trial parasite doses, 150 (n = 12) or 1,800 (n = 47) parasitised red blood cells (pRBC) as previously described29. Anticoagulated blood was collected for immunologic assessment at specific time points, before and during blood-stage infection. Antimalarial drugs were administered when volunteers reached a pre-determined parasitaemia of ≥1,000 parasites/mL (day 10 or 11; 150 pRBC and day 7 or 8; 1,800 pRBC) (Fig. 1A). Fresh whole blood or cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were used in flow cytometric assays. PBMCs were processed within 2 hours of collection. Experimental methods and studies were approved by Human Research Ethics Committees of QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute (P1479) and the Human Research Ethics Committees of the NT Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research (HREC 10/1431). All experimental methods were carried out in accordance with the NHMRC National Statement on Ethical Conduct of Human Research. Written and informed consent was obtained from all participants in the clinical trials. Clinical Trial Registrations; ACTRN12611001203943- registered 23/11/2011; ACTRN12612000323820- registered 21/03/2012; ACTRN12612000814875- 03/08/2012; ACTRN12613000565741-registered 17/05/2013; ACTRN12613001040752- 18/09/2013; NCT02281344- registered 30/10/2014. Details of the clinical trial protocol and clinical trial registrations are reported elsewhere29, 52.

Acute malaria

The number and phenotype of pDC were assessed in cryopreserved PBMCs collected from adults with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria (n = 10) as part of a pathophysiology study at Queen Elizabeth 1 and Kudat District Hospitals in Sabah, Malaysia53. PBMC samples were collected prior to commencing treatment, and again 14 to 28 days in a prospective fashion, after antimalarial drug treatment (Table 2). PBMCs from family or friends of patients were evaluated as controls (n = 5). Written informed consent was obtained from participants and the study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees of the NT Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research (HREC 10/1431) and the ethics committee of the Malaysian Ministry of Health (NMRR 10 754 6684). All experimental methods were carried out in accordance with the NHMRC National Statement on Ethical Conduct of Human Research.

Whole blood pDC and PBMC enumeration and activation

pDC were characterised as lineage (CD3, 14, 19, 20, 34, 56)−, HLA-DR+, CD11c−, CD123+ (Fig. 1B). In brief, 200 µL of blood or 3 million PBMC were stained with surface antibodies; CD3 (HIT3a), CD14 (HCD14), CD19 (HIB19), CD20 (2H7), CD34 (561), CD56 (HCD56), HLA-DR (L243), CD11c (B-Ly6), CD123 (6H6), CD86 (2331, FUN-1), CD80 (2D-10), CD40 (5C3) and HLA-A,B,C (W6/32). All antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences or Australian Biosearch, Biolegend. For whole blood, RBC were lysed with FACS lysing solution (BD, USA) and cells fixed with 1% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. Absolute numbers of pDC were determined by adding automated lymphocyte and monocyte counts (109 cells/L), dividing the sum by 100, multiplying the percentage of pDC, and multiplying the product by 1,000 to give the cell count/µL.

Apoptosis

Intracellular active caspase-3 was measured as previously described54. Briefly, 200 µL or 1,000 µL of blood was stained with surface antibodies, RBC were lysed with FACS lysing solution (BD, USA), cells were permeabilised using 1 × BD Perm/Wash™ (BD, USA) and stained with active caspase-3 antibody (C92-605, BD USA).

FITC-dextran uptake

pDC phagocytosis was assessed by uptake of 1 mg/mL FITC-dextran (Sigma, USA) after 60 min at 37 °C, or on ice as a control, and expressed as delta median fluorescence intensity (ΔMFI) (i.e. [MFI of cells at 37 °C]- [MFI control cells on ice]).

Intracellular cytokine staining

Cytokine production was assessed in PBMCs (2 million per well in RPMI 10% FCS (Invitrogen, USA)) or 1000 µL of WB stimulated with TLR agonists; TLR7: Imiquimod 2.5 µg/mL and TLR9: CpG ODN2216 50 ug/mL (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Protein transport inhibitor (Brefeldin A, BD, USA) was added after 2 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. At 6 h, cells were stained to identify pDC (including CD86 (IT2.2)), washed with 2% FCS/PBS, cells permeabilised with 1x Perm/Wash™ and stained with intracellular anti-TNF-α (MAB11), IL-12/IL-23p40 (C11.5), IL-10 (JES3-9D7), and IFN-α (LT27:295).

FACS data were acquired using a FACSCanto™ II (BD, USA) or Gallios™ (Beckman and Coulter, USA). Data were analysed using Kaluza® 1.3 (Beckman Coulter, USA).

pDC isolation and RNA Sequencing

RNA sequencing was performed on paired samples collected prior to and at peak-infection from five subjects experimentally infected with 1,800 P. falciparum pRBC. pDC were isolated from fresh PBMCs using the Human Diamond Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Gladbach, Germany). In brief, pDC were enriched according to the manufacturer’s instructions using CD304 (BDCA-4) conjugated microbeads and washed over MACs isolation columns. Purity of isolated pDC cell populations was checked using flow cytometry (day 0; median 99.3% [IQR 99.1–99.7%], day 7–8 median 99.6% [IQR 99.3–99.7%]) and the number of isolated pDC was estimated (day 0; median 14,336 cells [IQR 7,487–31,590 cells], day 7–8 median 38,491 cells [IQR 8,419–66,622 cells]. Isolated pDC were resuspended in RNAprotect (Qiagen, Australia) and stored immediately at −80 °C. RNA extraction and RNA-sequencing of five paired participant samples were conducted by Macrogen© (Seoul, Korea) using the Illumina TruSeq stranded mRNA LT sample kit and the HiSeq 2500 instrument. Transcriptome data were analysed using a modified version of an existing variant detection pipeline55 consisting of software STAR aligner56, samtools57, HTSeq58, and DESeq259. Reads were first aligned to human reference genome GRCh37 using STAR with the gene model set to gencode v19 annotation and quantmode set to TranscriptomeSAM. The alignment files were sorted with samtools and the resultant reads input to HTSeq to generate raw read counts using the union overlap resolution mode. Read counts were input to DESeq2 and a paired analysis performed for the five participants with baseline and peak parasitaemia data.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were undertaken using GraphPad Prism 6 (Graphpad Software Inc., USA). The Wilcoxon matched-pairs sign rank test was used to compare longitudinal data and a multiple comparisons test (1-way ANOVA) was used for comparison between no stimulation and TLR stimulation.

References

Eriksson, E., Sampaio, N. & Schofield, L. Toll-Like Receptors and Malaria–Sensing and Susceptibility. J Trop Dis 2, 2–84, doi:10.1128/IAI.00145-16 (2013).

Swiecki, M. & Colonna, M. The multifaceted biology of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Nature Reviews Immunology 15, 471–485, doi:10.1038/nri3865 (2015).

Diebold, S. S., Kaisho, T., Hemmi, H., Akira, S. & e Sousa, C. R. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science 303, 1529–1531, doi:10.1126/science.1093616 (2004).

Bauer, S. et al. Human TLR9 confers responsiveness to bacterial DNA via species-specific CpG motif recognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98, 9237–9242, doi:10.1073/pnas.161293498 (2001).

Haas, T. et al. The DNA sugar backbone 2′ deoxyribose determines toll-like receptor 9 activation. Immunity 28, 315–323, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2008.01.013 (2008).

Di Pucchio, T. et al. Direct proteasome-independent cross-presentation of viral antigen by plasmacytoid dendritic cells on major histocompatibility complex class I. Nature immunology 9, 551–557, doi:10.1038/ni.1602 (2008).

Fonteneau, J.-F. et al. Activation of influenza virus–specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells: a new role for plasmacytoid dendritic cells in adaptive immunity. Blood 101, 3520–3526, doi:10.1182/blood-2002-10-3063 (2003).

Jego, G. et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce plasma cell differentiation through type I interferon and interleukin 6. Immunity 19, 225–234, doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00208-5 (2003).

Poeck, H. et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells, antigen, and CpG-C license human B cells for plasma cell differentiation and immunoglobulin production in the absence of T-cell help. Blood 103, 3058–3064, doi:10.1182/blood-2003-08-2972 (2004).

Wu, X., Gowda, N. M., Kumar, S. & Gowda, D. C. Protein-DNA complex is the exclusive malaria parasite component that activates dendritic cells and triggers innate immune responses. J Immunol 184, 4338–4348, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0903824 (2010).

Sharma, S. et al. Innate immune recognition of an AT-rich stem-loop DNA motif in the Plasmodium falciparum genome. Immunity 35, 194–207, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.016 (2011).

Baccarella, A., Fontana, M. F., Chen, E. C. & Kim, C. C. Toll-like receptor 7 mediates early innate immune responses to malaria. Infection and immunity 81, 4431–4442, doi:10.1128/IAI.00923-13 (2013).

Liehl, P. et al. Host-cell sensors for Plasmodium activate innate immunity against liver-stage infection. Nature medicine 20, 47–53, doi:10.1038/nm.3424 (2014).

Voisine, C., Mastelic, B., Sponaas, A.-M. & Langhorne, J. Classical CD11c+ dendritic cells, not plasmacytoid dendritic cells, induce T cell responses to Plasmodium chabaudi malaria. International journal for parasitology 40, 711–719, doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.11.005 (2010).

Spaulding, E. et al. STING-Licensed Macrophages Prime Type I IFN Production by Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells in the Bone Marrow during Severe Plasmodium yoelii Malaria. PLoS Pathog 12, e1005975, doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005975 (2016).

DeWalick, S. et al. Cutting edge: conventional dendritic cells are the critical APC required for the induction of experimental cerebral malaria. The Journal of Immunology 178, 6033–7, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6033 (2007).

Yu, X. et al. Cross-Regulation of Two Type I Interferon Signaling Pathways in Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Controls Anti-malaria Immunity and Host Mortality. Immunity 45, 1093–1107, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.001 (2016).

Pichyangkul, S. et al. Malaria blood stage parasites activate human plasmacytoid dendritic cells and murine dendritic cells through a Toll-like receptor 9-dependent pathway. The Journal of Immunology 172, 4926–4933, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4926 (2004).

Pinzon-Charry, A. et al. Apoptosis and dysfunction of blood dendritic cells in patients with falciparum and vivax malaria. The Journal of experimental medicine 210, 1635–1646, doi:10.1084/jem.20121972 (2013).

Ibitokou, S. et al. Peripheral blood cell signatures of Plasmodium falciparum infection during pregnancy. PloS one 7, e49621, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049621 (2012).

Jangpatarapongsa, K. et al. Plasmodium vivax parasites alter the balance of myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells and the induction of regulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol 38, 2697–2705, doi:10.1002/eji.200838186 (2008).

Kho, S. et al. Preserved dendritic cell HLA-DR expression and reduced regulatory T cell activation in asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax infection. Infection and immunity 83, 3224–3232, doi:10.1128/IAI.00226-15 (2015).

Goncalves, R. M. et al. CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells, dendritic cells, and circulating cytokines in uncomplicated malaria: do different parasite species elicit similar host responses? Infect Immun 78, 4763–4772, doi:10.1128/IAI.00578-10 (2010).

Urban, B. C. et al. Frequencies of peripheral blood myeloid cells in healthy Kenyan children with alpha+ thalassemia and the sickle cell trait. Am J Trop Med Hyg 74, 578–584 (2006).

Arama, C. et al. Interethnic differences in antigen-presenting cell activation and TLR responses in Malian children during Plasmodium falciparum malaria. PLoS One 6, e18319, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018319 (2011).

Montes de Oca, M. et al. Type I Interferons Regulate Immune Responses in Humans with Blood-Stage Plasmodium falciparum Infection. Cell Reports 17, 399–412 (2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.015

Woodberry, T. et al. Low-Level Plasmodium falciparum Blood-Stage Infection Causes Dendritic Cell Apoptosis and Dysfunction in Healthy Volunteers. Journal of Infectious Diseases 206, 333–340, doi:10.1093/infdis/jis366 (2012).

Loughland, J. R. et al. Profoundly Reduced CD1c+ Myeloid Dendritic Cell HLA-DR and CD86 Expression and Increased Tumor Necrosis Factor Production in Experimental Human Blood-Stage Malaria Infection. Infection and immunity 84, 1403–1412, doi:10.1128/IAI.01522-15 (2016).

Rockett, R. et al. A real-time, quantitative PCR method using hydrolysis probes for the monitoring of Plasmodium falciparum load in experimentally infected human volunteers. Malaria journal 10, doi:10.1186/1475-2875-10-48 (2011).

Barry, S. et al. Roles of the N and C terminal domains of the interleukin-3 receptor α chain in receptor function. Blood 89, 842–852 (1997).

Colonna, M., Trinchieri, G. & Liu, Y. J. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in immunity. Nature immunology 5, 1219–1226, doi:10.1038/ni1141 (2004).

Grouard, G. et al. The enigmatic plasmacytoid T cells develop into dendritic cells with interleukin (IL)-3 and CD40-ligand. Journal of Experimental Medicine 185, 1101–1112, doi:10.1084/jem.185.6.1101 (1997).

Dzionek, A. et al. BDCA-2, BDCA-3, and BDCA-4: three markers for distinct subsets of dendritic cells in human peripheral blood. The Journal of Immunology 165, 6037–6046, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6037 (2000).

Cagnol, S. & Chambard, J. C. ERK and cell death: Mechanisms of ERK‐induced cell death–apoptosis, autophagy and senescence. FEBS Journal 277, 2–21, doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07366.x (2010).

Ito, T., Kanzler, H., Duramad, O., Cao, W. & Liu, Y.-J. Specialization, kinetics, and repertoire of type 1 interferon responses by human plasmacytoid predendritic cells. Blood 107, 2423–2431, doi:10.1182/blood-2005-07-2709 (2006).

Kobayashi, K. S. & van den Elsen, P. J. NLRC5: a key regulator of MHC class I-dependent immune responses. Nature Reviews Immunology 12, 813–820, doi:10.1038/nri3339 (2012).

Downs, I., Vijayan, S., Sidiq, T. & Kobayashi, K. S. CITA/NLRC5: A critical transcriptional regulator of MHC class I gene expression. BioFactors 42, 349–357, doi:10.1002/biof.v42.4 (2016).

Tel, J. et al. Human plasmacytoid dendritic cells efficiently cross-present exogenous Ags to CD8+ T cells despite lower Ag uptake than myeloid dendritic cell subsets. Blood 121, 459–467, doi:10.1182/blood-2012-06-435644 (2013).

Wykes, M. N. et al. Rodent blood-stage Plasmodium survive in dendritic cells that infect naive mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 11205–11210, doi:10.1073/pnas.1108579108 (2011).

Benkő, S., Kovács, E. G., Hezel, F. & Kufer, T. A. NLRC5 Functions beyond MHC I Regulation—What Do We Know So Far? Frontiers in Immunology 8, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00150 (2017).

Takayama, S. & Reed, J. C. Molecular chaperone targeting and regulation by BAG family proteins. Nature Cell Biology 3, E237–E241, doi:10.1038/ncb1001-e237 (2001).

Rosati, A. et al. BAG3 protein regulates caspase‐3 activation in HIV‐1‐infected human primary microglial cells. Journal of cellular physiology 218, 264–267, doi:10.1002/jcp.v218:2 (2009).

Pombo, D. J. et al. Immunity to malaria after administration of ultra-low doses of red cells infected with Plasmodium falciparum. The Lancet 360, 610–617, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09784-2 (2002).

Yang, Y.-C. et al. Human IL-3 (multi-CSF): identification by expression cloning of a novel hematopoietic growth factor related to murine IL-3. Cell 47, 3–10 (1986).

Kohara, H. et al. Development of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in bone marrow stromal cell niches requires CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling. Blood 110, 4153–4160, doi:10.1182/blood-2007-04-084210 (2007).

Yoneyama, H. et al. Evidence for recruitment of plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors to inflamed lymph nodes through high endothelial venules. International immunology 16, 915–928, doi:10.1093/intimm/dxh093 (2004).

Piqueras, B., Connolly, J., Freitas, H., Palucka, A. K. & Banchereau, J. Upon viral exposure, myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells produce 3 waves of distinct chemokines to recruit immune effectors. Blood 107, 2613–2618, doi:10.1182/blood-2005-07-2965 (2006).

Zheng, W. et al. CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells prevent the development of Th1 immune response by inhibition of dendritic cell function during the early stage of Plasmodium yoelii infection in susceptible BALB/c mice. Folia parasitologica 56, 242–50, doi:10.14411/fp.2009.028 (2009).

Swiecki, M., Wang, Y., Gilfillan, S. & Colonna, M. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells contribute to systemic but not local antiviral responses to HSV infections. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003728, doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003728 (2013).

Lehmann, C. et al. Longitudinal analysis of distribution and function of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in peripheral blood and gut mucosa of HIV infected patients. Journal of Infectious Diseases 209, 940–949, doi:10.1093/infdis/jit612 (2014).

Haque, A. et al. Type I interferons suppress CD4+ T‐cell‐dependent parasite control during blood‐stage Plasmodium infection. European journal of immunology 41, 2688–2698, doi:10.1002/eji.201141539 (2011).

McCarthy, J. S. et al. A Pilot Randomised Trial of Induced Blood-Stage Plasmodium falciparum Infections in Healthy Volunteers for Testing Efficacy of New Antimalarial Drugs. PLoS ONE 6, e21914, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021914 (2011).

Barber, B. E. et al. A prospective comparative study of knowlesi, falciparum, and vivax malaria in Sabah, Malaysia: high proportion with severe disease from Plasmodium knowlesi and Plasmodium vivax but no mortality with early referral and artesunate therapy. Clinical infectious diseases 56, 383–397, doi:10.1093/cid/cis902 (2013).

Jerome, K., Sloan, D. & Aubert, M. Measurement of CTL-induced cytotoxicity: the caspase 3 assay. Apoptosis 8, 563–571, doi:10.1023/A:1026123223387 (2003).

Field, M. A., Cho, V., Andrews, T. D. & Goodnow, C. C. Reliably detecting clinically important variants requires both combined variant calls and optimized filtering strategies. PloS one 10, e0143199, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143199 (2015).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21, doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 (2013).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079, doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 (2009).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics, Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169, doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638 (2015).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome biology 15, 12, doi:10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Q-pharm staff who conducted the human infection studies and in particular Dr Suzanne Elliot, Nannette Douglas and Gem Mackenroth for supporting the research. We thank Dr Paul Griffin for advice and technical assistance. We thank the Australian Red Cross Blood Service for their support. The clinical trials from which the samples were drawn were funded by the Medicines for Malaria Venture. We thank the volunteers who participated in all clinical trials. We thank all the clinical malaria patients and clinical staff from Queen Elizabeth 1 and Kudat District Hospitals involved in their care. This work was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) [Project Grant 1021198, Program Grant 1037304 and fellowships to NMA, JSM, CE, BEB, DLD, MFG and GM and an APA PhD scholarship to JRL and MJG. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the NHMRC. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.R.L., G.M. and T.W. conceived and designed the experiments and prepared the manuscript. J.R.L., G.M., T.W., P.E.T. and M.M.O. performed the experiments with assistance from K.A.P. and F.H.A. J.R.L., G.M., T.W., D.S.S. and M.F. analysed the data. T.W., B.E.B., M.J.G. and N.M.A. provided Malaysian clinical samples and data. D.S. and M.F. performed RNA sequencing analysis and contributed to manuscript preparation. N.M.A., M.F.G., C.R.E. and D.L.D. provided intellectual input and assisted with manuscript preparation. J.S.M. conducted the clinical trial and assisted in manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Loughland, J.R., Minigo, G., Sarovich, D.S. et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells appear inactive during sub-microscopic Plasmodium falciparum blood-stage infection, yet retain their ability to respond to TLR stimulation. Sci Rep 7, 2596 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02096-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02096-2

This article is cited by

-

Single cell transcriptomics shows that malaria promotes unique regulatory responses across multiple immune cell subsets

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Reduced circulating dendritic cells in acute Plasmodium knowlesi and Plasmodium falciparum malaria despite elevated plasma Flt3 ligand levels

Malaria Journal (2021)

-

Dendritic cell responses to Plasmodium falciparum in a malaria-endemic setting

Malaria Journal (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.