Abstract

A reentrant temperature dependence of the normal state resistance often referred to as the N-shaped temperature dependence, is omnipresent in disordered superconductors – ranging from high-temperature cuprates to ultrathin superconducting films – that experience superconductor-to-insulator transition. Yet, despite the ubiquity of this phenomenon its origin still remains a subject of debate. Here we investigate strongly disordered superconducting TiN films and demonstrate universality of the reentrant behavior. We offer a quantitative description of the N-shaped resistance curve. We show that upon cooling down the resistance first decreases linearly with temperature and then passes through the minimum that marks the 3D–2D crossover in the system. In the 2D temperature range the resistance first grows with decreasing temperature due to quantum contributions and eventually drops to zero as the system falls into a superconducting state. Our findings demonstrate the prime importance of disorder in dimensional crossover effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reentrant temperature dependence of the normal state resistance is found in a wide variety of disordered superconducting systems. With temperature decreasing, the resistance first decreases and then upturns upon further cooling down, and, finally, drops down to zero, see Fig. 1a,b. Similar N-shaped temperature dependence is observed in thin films of conventional superconductors PtSi1 and AlGe2. In the boron-doped granular diamond3 this behaviour is interpreted in the framework of an empirical model based on the metal-bosonic insulator-superconductor transitions induced by a granularity-correlated disorder. In high-T c cuprates this behavior occurs often4,5,6,7,8,9,10, but is not thoroughly understood yet and is described in terms of the scaling functions10, 11 or attributed to the emergence of the pseudogap phase12. As cuprates are generically a stack of conducting CuO plains, a natural idea arises that it is the study of their elemental structural unit, two-dimensional disordered superconductor, that may provide a critical insight into the physics of high-T c .

Reentrant temperature dependence of the resistance and phase diagram. (a) Resistance per square vs. temperature for five TiN films with different thicknesses d and different resistances at room temperature R 300. (b,c) The enlarged areas from panel (a) for sample d = 7 nm. (b) Magnified representation of R(T) above the superconducting transition. All the samples exhibit the same behaviour. Arrows mark temperatures T* and T max . Dashed line corresponds to R ∝ T. (c) Magnified representation of R(T) near the superconducting transition. Arrow marks the superconducting critical temperature T c determined from the quantum contribution fits (see Fig. 3a and details in the text). (d) The phase diagram for low-T c thin TiN films in conductance (G 300 = 1/R 300)-temperature (T) coordinates. Temperatures T*, T max , T c separate four distinct regimes of R(T). The five points at higher G correspond to films in (a). Three points for lower G (i.e. lower T c ) corresponds to films from ref. 14, which have no T* value since in these films R(T) increases with cooling from room temperature.

Here we undertake a careful study of the strongly disordered ultrathin TiN superconducting film and find that its reentrant behavior occurs due to combined effects of the crossover from the 3D behavior determined by the Bloch-Grüneisen law to the quasi-2D behavior governed by competing quantum contributions to conductivity. We show that the shift from the downturn to upturn of the resistance occurs once the thermal coherence length L T matches the thickness of the film d. We summarize our results by phase diagram in the conductance-temperature coordinates. Our findings demonstrate the important role of disorder in dimensional crossover effects.

Experimental Techniques

The data are taken on thin, 7 ≤ d ≤ 23 nm, TiN films formed on a Si/SiO2 substrate by the atomic layer deposition. The films are atomically smooth polycrystalline with the densely-packed crystallites and are similar to those analyzed in refs 13, 14. Here we deal with homogeneously disordered films i.e. films with \({k}_{F}l\mathop{ < }\limits_{ \tilde {}}10\) and characteristic size of structural inhomogeneities δx less than characteristic lengths of the system. In this case the most reliable measure of disorder is the resistance per square \({R}_{\square }\) (in other words the conductance G) of the system15. The parameters of the sample are calculated in the approximation of the parabolic dispersion law, from the superconducting critical temperature T c , and carrier density n is found from the measurements of the Hall effect at T = 10 K. The samples are patterned into bridges 50 μm wide and 250 μm long. Transport measurements are carried out using the low-frequency ac technique in a four-probe configuration.

Experimental Results

Temperature dependencies of the resistance per square, \({R}_{\square }(T)\), at zero magnetic field for TiN films with different thicknesses and different resistances at room temperature are shown in Fig. 1a. As a function of the decreasing temperature, the resistance first decreases (dR/dT > 0) linearly at high temperatures (see Fig. 1b), then deviates upwards from R ∝ T reaching the minimum at some temperature T*. The temperature T* grows with the film resistance R 300, i.e. with the increasing degree of disorder (Fig. 1d). Upon further cooling, \({R}_{\square }(T)\) increases (dR/dT < 0) and passes the local maximum at T max to drop (dR/dT > 0) down to zero resistance below the superconducting critical temperature T c (see Fig. 1c). The superconducting transition temperature T c is defined as an adjusting parameter in quantum contributions to conductivity14, see also the discussion below, and is located at the foot of the \({R}_{\square }(T)\) curve. A crude estimate gives \(R({T}_{c})\simeq 0.1{R}_{max}\), where R max is the resistance at T max 14. The temperature T c decreases with the decreasing films thickness, i.e. with the growth of the films’ resistance per square at room temperature R 300. The latter is a convenient parameter to characterize the degree of disorder in films. Figure 1d summarizes our observations into a phase diagram in the conductance-temperature coordinates (G; T) where G = 1/R 300. The obtained phase diagram of TiN films resembles those for the high-T c superconductors16, 17 with the doping x being replaced by conductivity, G. The diagram comprises the four regions corresponding to the distinct regimes of R(T) dependence. These regions are separated by the characteristic temperatures T*, T max , and T c .

Discussion

The linear high-temperature behavior of R(T) in Fig. 1a,b follows from the high-temperature asymptote of the so-called Bloch-Grüneisen formula18,19,20,21

where Θ is the Debye temperature and C is the material constant (see Methods for details). The approximation R BG ∝ T holds down18 to temperatures \(T\simeq {\rm{\Theta }}/3\). With the decreasing temperature, the upturn from the foregoing linear dependence occurs and upon passing the minimum at T* the resistance starts to increase. This growth of the resistance resembles the quasi-2D metallic behaviour dominated by the quantum contributions to conductivity. One thus can justly conjecture that T* marks the crossover from the 3D to the quasi-2D behavior of R(T) around T*. To check it let us compare the film thickness d and two characteristic lengths of the system: (i) the phase-coherence length,

where τ ϕ is the phase decoherence time; (ii) the thermal coherence length,

where k B is the Boltzmann constant, and diffusion coefficient D is refs 22, 23:

where γ is Euler’s constant γ = 1.781, and B c2(0) is the upper critical field at T = 0 (see SI for details). The quasiparticle description holds for \({k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\gg \hslash /{\tau }_{\phi }\) 24 which implies \({L}_{T}\ll {L}_{\phi }\). Therefore, it is the thermal coherence length L T that controls the effective dimensionality of the system (Fig. 2a). When the length L T exceeds the thickness d (provided that the lateral size \(L\gg d\)) the system becomes two-dimentional with respect to effects of the electron-electron interaction25. The ratio d/L T (T*) as a function of the sample resistance at room temperature R 300 is shown in Fig. 2b. The temperature T = T* marks the moment where becomes \(d\simeq {L}_{T}\) hence the 3D–2D crossover, so that \(d\mathop{ > }\limits_{ \tilde {}}{L}_{T}\) at T > T* and the system is three dimensional, whereas at T < T*, \(d\mathop{ < }\limits_{ \tilde {}}{L}_{T}\) and the system turns two-dimensional.

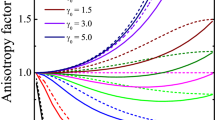

Dimensional crossover and quantum contributions fits. (a) A sketch of the temperature dependence of thermal coherence length \({L}_{T}\propto 1/\sqrt{T}\) (solid line). The rectangle confines the region where L T exceeds the film thickness d (dashed line). (b) The ratio of the film thickness to thermal coherence length d/L T (T*) at the crossover temperature T* vs. resistance at room temperature R 300. (c) The dependence R(T) from Fig. 1a replotted as a dimensionless conductance G/G 00 as function of the temperature in the logarithmic scale for samples d = 10 nm and d = 7 nm. Dash-dotted lines correspond to G/G 00 ∝ ln T. (d) The reduced resistance R/R* vs reduced temperature T/T*, where T* and R* are the temperature and resistance at the local minimum. Symbols stand for experimental data, solid lines are fits by Eqs (7) and (8). Note, that three samples with lowest T c did not show a R(T) minimum. Dashed lines are fits accounting for all the quantum contributions to conductivity (see Fig. 3a and the discussion in the text).

The same data as in Fig. 1b but replotted as the dimensionless conductance G/G 00 are shown in Fig. 2c in the semilogarithmic scale. This representation reveals the logarithmic temperature dependence of the conductance which is typical for two-dimensional (2D) metal where the effects of weak localization (WL) and electron-electron interaction in diffusion channel (ID) are enhanced by dimensionality14, 25. In the 2D case the WL and ID contributions to conductivity are

where \({G}_{00}={e}^{2}/\mathrm{(2}{\pi }^{2}\hslash )\), a = 1 provided the spin-orbit scattering is neglected (\({\tau }_{\phi }\ll {\tau }_{so}\)) and a = −1/2 for \({\tau }_{\phi }\gg {\tau }_{so}\), p is the exponent in the temperature dependence of the phase decoherence time \({\tau }_{\phi }\propto {T}^{-p}\), and \({A}_{ID}\simeq 1\) is a constant accounting for the Coulomb screening. At low temperatures where electron-electron scattering dominates, \({\tau }_{\phi }\propto {T}^{-1}\), i.e. p = 1. At high temperatures where the electron-phonon interaction becomes relevant, p = 2 in the presence of disorder. Hence at high temperatures \(A\mathop{ < }\limits_{ \tilde {}}3\) is expected for homogeneously disordered films.

We are now equipped to fully describe the behavior of R(T) above T max as a result of superposition of quantum contributions to conductivity (WL+ID) and the Bloch-Grüneisen law. In the linear regime they just add to each other:

where R BG(T) is defined in Eq. (1), R res is a residual resistance. In our case this residual resistance is given by

where ΔG WL+ID is defined in Eq. (5) and R 0 is the residual resistance due to defect scattering, proportional to normal resistance of the sample (see Methods). Figure 2d demonstrates an excellent fitting by Eq. (7) to the experimental data, capturing the original decrease of R(T) with temperature decreasing, the minimum, and the subsequent growth. The parameter A in Eq. (5) is A = 2.85 ± 0.15, which agrees with theoretical predictions. The Debye temperature is Θ = 450 ± 10 K i. e. is 30% less than Θ in the bulk material26 (the decrease of the Debye temperature with the decrease of the system dimensionality has been reported before27,28,29). The values of C are of same orders as those previously found in other superconducting materials30, 31. To conclude here, the minimum in R(T) results from the dimensional crossover between the 3D behavior governed by the Bloch-Grüneisen formula and the 2D region, where R(T) is controlled by quantum contributions. The fit works perfectly down to temperatures \(T\mathop{ < }\limits_{ \tilde {}}10{T}_{c}\) where superconducting fluctuations (ΔG SF) start to dominate.

Below T* the resistance increases, reaches the maximum, and, finally, decreases down to zero (Figs 2d and 3a). This non-monotonic R(T) is similar to that of thinner high-resistance samples and has been fully analyzed14. Quantum correction formulas fit perfectly the experimental data. In passing, following14, these fits, in which T c plays the role of the adjustable parameter, yield the precise value of the critical temperature (Fig. 3a). Figure 3b shows that the suppression of the critical temperature T c with the increase of the normal state resistance R 300 follows the celebrated Finkelstein’s formula32:

where r = G 00 · R sq , R sq is the resistance per square, \(\gamma =\,\mathrm{ln}\,[\hslash /(k{T}_{c0}\tau )]\). The best fit of Eq. (9) to experimental data is achieved at T c0 = 3.4 K, τ = 7.5 · 10−15 s, yielding γ = 5.73, the found values agreeing fairly well (see Fig. 3b) with the earlier data21 for TiN.

Superconducting critical temperature. (a) Determination of T c from quantum contributions to the conductivity. Solid lines: experimental resistances per square vs. temperature for three TiN film with different thicknesses d and different resistances at room temperature R 300. Dashed lines are the same as in Fig. 2d, the fits account for all quantum contributions to conductivity. Arrows mark the respective superconducting critical temperatures T c . (b) The superconducting critical temperature T c vs. R 300 for the TiN films shown in Fig. 1a and published in refs 14, 46, 47. The solid line is the theoretical fitting by Eq. (9) with the adjustable parameter \(\gamma =\,\mathrm{ln}\,[\hslash /(k{T}_{c0}\tau )]=5.73\), where T c0 = 3.4 K and τ = 7.3 · 10−15 s.

Our results are summarized in a phase diagram (Fig. 1d) displaying the effective dimensionality of the system and the corresponding mechanisms of the conductivity. We identify four distinct regimes. At high temperatures, T > T*, where \(d\mathop{ > }\limits_{ \tilde {}}{L}_{T}\), the resistance depends linearly on temperature and the system is a 3D metal. The boundary for this region is calculated from the condition dR/dT = 0, see Eqs (1) and (7). Down in temperature, at T < T*, \(d\mathop{ < }\limits_{ \tilde {}}{L}_{T}\), and the system becomes two-dimensional. The resistance in this region is dominated by quantum contributions from electron-electron interaction and weak localization. The boundary T max (1/R) separating this region and the region controlled by superconducting fluctuations is found from the condition \({\rm{\Delta }}{G}^{SF}\simeq {\rm{\Delta }}{G}^{WL+ID}\) as in ref. 14 (see SI). Below T max electronic transport in the system is governed by superconducting fluctuations. Finally, the line that marks formation of the Cooper condensate is calculated from Eq. (9).

Let us discuss the high-G region of this diagram. The temperature dependence R(T) of films with higher G 300 shows wider and less-pronounced minimum at T* and maximum T max , that is reflected by increase of error bars with G 300. The experimental T max (G) dependence seems to show a maximum and subsequent decease. This is because of the point T max coming from the last sample with d = 23 nm. This untoward sample segregates from the common trend in saturation T max (G). However, T*(G) corresponding to this sample obeys the general saturation trend and demonstrates the reasonable d/L(T*) value in Fig. 2b supporting the idea of 3D–2D dimensional crossover taking place in minimum in R(T). The theoretical dependence T max (G) saturates with increasing G (dashed line in Fig. 1d) as well as theoretical T*(G). So the natural question arises: what would we observe at higher G, that we did not test in experiment? It is clearly seen that for both quantities T* and T max , the error of determination increases with G. So, it seems like at higher G both this features of R(T) would be blurred and the dimensional crossover would gradually fade away towards thicker films that would remain three-dimensional at all temperatures. On the other hand, even in 3D superconducting films, there will be the N-shaped region of R(T), weakly pronounced though, associated with saturation of Drude conductivity and the influence of 3D quantum contributions to conductivity. Unfortunately we do not have films with higher conductance G to make decisive measurements.

Now we briefly compare the behaviour of TiN films and cuprates. The similarity of cuprates and thin films of conventional superconductors has been demonstrated in a various experiments. Namely, ultrathin disordered films of TiN exhibit the pseudogap pretty similar to that of the high-T c 33. The former stems from the appreciable depletion of the density of the electronic states (DOS) by superconducting fluctuations favored by two-dimensionality and disorder. The behavior of the mid-infrared optical conductivity of TiN is similar to pseudogap features of high-T c and is described in terms of fluctuation dominated 2D transport34. Several studies pointed a peak in the Nernst effect in both high-T c 35 and thin-films of conventional superconductors36, 37. The N-shaped temperature dependence offers another example of similarity between the high-T c and disordered thin films. However, the situation in high-T c is by far more complicated because of other interfering orders, including various forms of charge-density-waves, spin-density-waves, and electron-nematic order38, to name a few. For example, in underdoped cuprates YBCO the N-shaped temperature dependences of R(T) is attributed to formation of 1D conducting charge stripes, and the experimental data seem to well agree with the expected scaling behavior11. In BSCCO-2212:La above the critical doping, the reentrant behavior is well described by the model of the two-component scaling function that describes the coexistence of the weakly insulating phase and the superconductive fluctuating phase consistent with the electronic phase-separation mechanism driven by carrier-carrier correlations10. This scaling was not observed in our data (see SI Fig. 3), despite that one would expect TiN films to demonstrate phase separation on the brink of superconductor-insulator transition as well39. Another complication in comparing normal state properties in cuprates and those in superconducting thin films may stem from the supposed non-Fermi-liquid nature of electrons in the former. This means that the analysis of the N-shaped R(T) based on the standard electron-phonon scattering (Eq. (1)) and quantum corrections (Eq. (5)) considerations should be applied to cuprates with certain reservations and caution. Yet, the observation of 2D-like weak localization was reported, for example, in nonsuperconducting overdoped TlBCO single crystals40. Since in high-T c the conductivity along the layers is much greater than that across the layers, the electrons there can be viewed as confined to individual layers41. Therefore, the corresponding quantum contributions are described by the same Eqs (5) and (6) butwith \(A\gg 1\) 42. As for the fluctuation phenomena, the superconducting fluctuations above T c are prominently present in high-T c compounds because of their extreme anisotropy43, 44. Concluding here the hole situation in cuprates calls for more thorough research.

Conclusion

We construct the phase diagram displaying the effective dimensionality of the TiN films and the corresponding mechanisms of the conductivity. We show that the minimum in R(T) marks the crossover between the 3D and 2D behaviours at the temperature where the thermal coherence length L T compares to the film thickness. We demonstrate that the total N-shaped temperature dependence of the TiN film resistance results from the intertwined effects of the Bloch-Grüneisen law and quantum contributions to conductivity. The observed N-shaped dependence resembles strikingly the temperature behaviour of the resistance found in a wide variety of disordered systems and materials.

Methods

Numerical parameters

The material constant C in Eq. (1) is ref. 20:

here m and e are mass and charge of an electron respectively, n is electron density, M is mass of an atom, a is lattice constant, c 0 is the material parameter depending on the velocity of electrons at the Fermi surface; usually c 0 = 1 ÷ 10 eV20. Taking m = 2m 0 45, the average TiN atomic mass \(M=(1/2)({M}_{{\rm{Ti}}}+{M}_{{\rm{N}}})\simeq 5\cdot {10}^{-26}\,{\rm{kg}}\), lattice constant \(a\simeq 0.4\,{\rm{nm}}\) and \({c}_{0}\simeq 8\,{\rm{eV}}\) the estimated values of C match those determined from fitting of experimental R(T) dependencies.

d, nm | R 300, Ω | k F l | D, cm2/s | C, Ω | R 0, Ω |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

7 | 334 | 4.9 | 0.68 | 163.5 | 314.5 |

10 | 216 | 5.8 | 0.76 | 159 | 198.7 |

12 | 165 | 6.2 | 0.8 | 105 | 150.9 |

18 | 90 | 7.4 | 0.82 | 95 | 81.5 |

23 | 65 | 7.9 | 0.87 | 69 | 58.8 |

References

Ishida, S., Murase, K., Gamo, K. & Namba, S. Quantum Transport in PtSi Thin Films and Narrow Wires. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 64, 858, doi:10.1143/JPSJ.64.858 (1995).

Zaken, E. & Rosenbaum, R. Superconducting fluctuation conductivity in granular Al-Ge films above the metal-insulator transition. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 6, 9981 (1994).

Zhang, G. et al. Majorana Fermions and a Topological Phase Transition in Semiconductor-Superconductor Heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 077001 (2013).

Peng, Y. et al. Disappearance of nodal gap across the insulator-superconductor transition in a copper-oxide superconductor. Nat. Com. 4, 2459 (2013).

Takagi, H. et al. Systematic evolution of temperature-dependent resistivity in La2−x Sr x CuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 2975 (1992).

Ono, S. et al. Metal-to-insulator crossover in the low-temperature normal state of Bi2Sr2−x La x CuO6+δ . Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 638 (2000).

Semba, K. & Matsuda, A. Superconductor-to-insulator transition and transport properties of underdoped Yba2Cu3O y crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 496 (2001).

Komiya, S., Chen, H.-D., Zhang, S.-C. & Ando, Y. Magic Doping Fractions for High-Temperature Superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 207004 (2005).

Rullier-Albenque, F., Alloul, H., Balakirev, F. & Proust, C. Disorder, metal-insulator crossover and phase diagram in high-Tc cuprates. EPL 81, 37008 (2008).

Oh, S., Crane, T. A., Van Harlingen, D. J. & Eckstein, J. N. Doping Controlled Superconductor-Insulator Transition in Bi2Sr2−x La x CaCu2O8+δ . Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 107003 (2006).

Moshchalkov, V. V., Vanacken, J. & Trappeniers, L. Phase diagram of high-T c cuprates: Stripes, pseudogap, and effective dimensionality. Phys. Rev. B 64, 214504 (2001).

Daou, R. et al. Linear temperature dependence of resistivity and change in the Fermi surface at the pseudogap critical point of a high-Tc superconductor. Nature Physics 5, 31 (2009).

Baturina, T. I. et al. Dual threshold diode based on the superconductor-to-insulator transition in ultrathin TiN films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 042601 (2013).

Baturina, T. I. et al. Superconducting phase transitions in ultrathin TiN films. Europhys. Lett. 97, 17012 (2012).

Larkin, A. & Varlamov, A. Theory of Fluctuations in Superconductors (Clarendon Press, Oxford) (2005).

Buchanan, M. Mind the pseudogap. Nature 409, 8 (2001).

Timusk, T. & Statt, B. The pseudogap in high-temperature superconductors: an experimental survey. Rep. Prog. Phys. 62, 61 (1999).

Abrikosov, A. A. Fundamentals of the Theory of Metals (North Holland, Amsterdam 1988).

Ziman, J. M. Electrons and Phonons (Clarendon, Oxford 1960).

Kraposhin, V. S. Physical Encyclopedia 1, 297 (Soviet Encyclopedia, Moscow 1969).

Hadacek, N., Sanquer, M. & Villégier, J. C. Double reentrant superconductor-insulator transition in thin TiN films. Phys. Rev. B 69, 024505 (2004).

Helfand, E. & Werthamer, N. R. Temperature and purity dependence of the superconducting critical field, H c2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 686–688 (1964).

Helfand, E. & Werthamer, N. R. Temperature and Purity Dependence of the Superconducting Critical Field, H c2. II Phys. Rev. Lett. 147, 288–294 (1966).

Altshuler, B. L., Aronov, A. G. & Khmelnitsky, D. E. Effects of electron-electron collisions with small energy transfers on quantum localisation. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 15, 7367 (1982).

Altshuler, B. L. & Aronov, A. G. Electron-Electron Interactions in Disordered Systems (North Holland, Amsterdam 1985).

Pierson, H. O. Handbook of refractory carbides and nitrides: properties, characteristics, processing and applications (Noyes publications, Westwood, New Jersey 1996).

Borca, C. N. et al. Effective surface Debye temperature for NiMnSb(100) epitaxial films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 77, 88 (2000).

Bid, A., Bora, A. & Raychaudhuri, A. K. Temperature dependence of the resistance of metallic nanowires of diameter ≥15 nm: Applicability of Bloch-Gruneisen theorem. Phys. Rev. B 74, 035426 (2006).

Wang, Y. et al. The Debye characteristic temperature of nanodiamond thin films. Proc. of SPIE 7381, 73810R (2009).

Pronin, A. V., Gorshunov, B. P., Volkov, A. A. & Kozlov, G. V. Submillimeter electrodynamics of niobium carbide thin films: superconductivity and size effect. JETP 82, 790 (1996).

Gasparov, V. A., Sidorov, N. S., Zverkova, I. I. & Kulakov, M. P. Electron transport in diborides: Observation of superconductivity in ZrB2. JETP Letters 73, 532 (2001).

Finkelstein, A. M. Superconducting transition temperature in amorphous films. JETP Lett 45, 46 (1987).

Sacépé, B. et al. Pseudogap in a thin film of a conventional superconductor. Nat. Com. 1, 14 (2010).

Pfuner, F. et al. Optical properties of TiN thin films close to the superconductor-insulator transition. New J. Phys. 11, 113017 (2009).

Chang, J. et al. Decrease of upper critical field with underdoping in cuprate superconductors. Nat. Phys. 8, 751 (2012).

Pourret, A. et al. Observation of the Nernst signal generated by fluctuating Cooper pairs. Nat. Phys. 2, 683 (2006).

Spathis, P., Aubin, H., Pourret, A. & Behnia, K. Nernst effect in the phase-fluctuating superconductor InO x . Europhys. Lett. 83, 57005 (2008).

Keimer, B., Kivelson, S. A., Norman, M. R., Uchida, S. & Zaanen, J. From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper oxides. Nature 518, 179 (2015).

Baturina, T. I. & Vinokur, V. M. Superinsulator-superconductor duality in two dimensions. Annals of Physics 331, 236–257 (2013).

Rullier-Albenque, F., Alloul, H. & Tourbot, R. Disorder and Transport in Cuprates: Weak Localization and Magnetic Contributions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 157001 (2001).

Millis, A. J. Gaps and Our Understanding. Science 314, 1888 (2006).

Lin, Y. K., Novet, T., Johnson, D. C. & Valles, J. M. Dimensional crossover in the low-temperature transport properties of annealed amorphous Fe/Si multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 48, 14608 (1993).

Varlamov, A. A., Balestrino, G., Milani, E. & Livanov, D. The role of density of states fluctuations in the normal state properties of high T c superconductors. Advances in Physics 48, 655–783 (1999).

Vanacken, J. & Moshchalkov, V. V. High-Temperature Superconductors, Edited by Qiu, X. G. (Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, United Kingdom 2011).

Patsalas, P. et al. Combined electrical and mechanical properties of titanium nitride thin films as metallization materials. J. Appl. Phys. 86, 5296 (1999).

Baturina, T. I. et al. Quantum-critical region of the disorder-driven superconductor-insulator transition. Physica C 468, 316 (2008).

Kalok, D. et al. Non-linear conduction in the critical region of the superconductor-insulator transition in TiN thin films. JPCS 400, 022042 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The experimental work was supported by RSCF (Grant No. 14-22-00143). The work of A.Yu.M and S.V.P. on numerical analysis was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Grant No. 16-02-0080316-a). The work of V.M.V. was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division. S.V.P. would like to thank R.I. Mazurenko for fruitful discussions. T.I.B. acknowledges support from the Consejería de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (Comunidad de Madrid) through the talent attraction program, Ref. 2016-T3/IND-1839.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.I.B. conceived and initiated the project. A.Yu.M., S.V.P. performed the experiments. M.R.B. fabricated samples. A.Yu.M., T.I.B., S.V.P., V.M.V. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

41598_2017_1753_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Information: \\ Reentrant Resistive Behavior and Dimensional Crossover in Disordered Superconducting TiN Films

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Postolova, S.V., Mironov, A.Y., Baklanov, M.R. et al. Reentrant Resistive Behavior and Dimensional Crossover in Disordered Superconducting TiN Films. Sci Rep 7, 1718 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01753-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01753-w

This article is cited by

-

Granularity mediated multiple reentrances with negative magnetoresistance in disordered TiN thin films

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

A robust nitridation technique for fabrication of disordered superconducting TiN thin films featuring phase slip events

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Superconducting phase transitions in disordered NbTiN films

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Dynamical instability of the electric transport in superconductors

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.