Abstract

In this study, we evaluated the consequences of reducing Galectin-1 (Gal-1) in the tumor micro-environment (TME) of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), via nose-to-brain transport. Gal-1 is overexpressed in GBM and drives chemo- and immunotherapy resistance. To promote nose-to-brain transport, we designed siRNA targeting Gal-1 (siGal-1) loaded chitosan nanoparticles that silence Gal-1 in the TME. Intranasal siGal-1 delivery induces a remarkable switch in the TME composition, with reduced myeloid suppressor cells and regulatory T cells, and increased CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Gal-1 knock-down reduces macrophages’ polarization switch from M1 (pro-inflammatory) to M2 (anti-inflammatory) during GBM progression. These changes are accompanied by normalization of the tumor vasculature and increased survival for tumor bearing mice. The combination of siGal-1 treatment with temozolomide or immunotherapy (dendritic cell vaccination and PD-1 blocking) displays synergistic effects, increasing the survival of tumor bearing mice. Moreover, we could confirm the role of Gal-1 on lymphocytes in GBM patients by matching the Gal-1 expression and their T cell signatures. These findings indicate that intranasal siGal-1 nanoparticle delivery could be a valuable adjuvant treatment to increase the efficiency of immune-checkpoint blockade and chemotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Central nervous system neoplasms are subtyped in either primary or secondary brain tumors. Among primary brain tumors, glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most prevalent high grade glioma1, 2. GBM displays highly necrotic, hypoxic and mitotic areas, hallmarks of high grade neoplasms3. Current therapy consists of debulking, followed by chemoradiotherapy, resulting in a median survival of 14.6 months4. Novel clinical treatment regimens have so far had little impact on GBM patient survival5. The field of immunotherapy offers promising new avenues6 with dendritic cell (DC) vaccinations7,8,9,10 or recent clinical trials targeting Programmed Cell Death protein-1 (PD-1) in order to regulate the immune checkpoint in GBM (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02335918, NCT02529072). Targeting PD-1 aims to release the break on the adaptive immune response against tumour cells, leading to increased recruitement and activation of cytotoxic T cells (CTLs).

Despite numerous clinical trials, and novel biological compounds being tested, the poor prognosis for GBM patients remains largely unchanged11, 12. The uniquely immune-priviledged microenvironment of the central nervous system proves to be particularly challenging for the efficacy of immunotherapy in GBM. Therefore, the development of new therapies with improved activity at the tumor site will require a deeper understanding of the dynamic tumor micro environment (TME) in GBM. Recent findings identified a pivotal tumour promoting role for Galectin-1 (Gal-1), a 14 kDa lactose binding lectin, in the TME of GBM13, 14. Gal-1 increases the migration of GBM cells and their resistance against chemotherapy (i.e. temozolomide, TMZ)15,16,17. Gal-1 has further been correlated with the proliferative gain-of-function properties of tumor cells involving anchoring the RAS proto-oncogene at the innerplasmatic membrane13, 18. In addition, immunosuppressive and angiogenic properties of Gal-1 have been suggested in the context of GBM17, 19. Rubinstein et al. noticed that blockade of Gal-1 synthesis in tumor cells allows the generation of a tumor-specific Th1-type immune response in vivo 20. Interestingly, Gal-1 can be upregulated in tumors during radiotherapy, thereby sustaining immune suppression21. These features pinpoint Gal-1 as a crucial molecule in shaping the TME in GBM. Indeed, intraventricular delivery of siGal-1 can sensitize GBM cells to TMZ while reducing the abnormal tumour vasculature17. However, the invasive procedure of intraventricular administration is associated with inherent adverse events such as inflammation.

As a non-invasive alternative route to deliver therapeutic agents into the central nervous system, and more specifically into the TME of GBM, we proposed the nose-to-brain transport via intranasal administration22. In recent years, the intranasal transport towards the central nervous system has gained a lot of momentum, and even reached the clinical stage because of patient comfort and reduced adverse secondary effects23,24,25. Previously we described that chitosan nanoparticles are able to transport siGal-1 to the TME in GBM26. This leads to a specific degradation of Gal-1, while other galectines (such as Gal-3) are not affected. After administriation in the nasal cavity, siGal-1 is rapidly transported to the olfactory bulbus and spread within the inoculated glioma TME. Functionally, we observed a strong reduction of Gal-1 after siGal-1 treatment and subsequent cleaved Gal-1 mRNA fragments in GL261 glioma tumors. As such, we were able to provide strong evidence for in vivo RNAi mediated targeted reduction of Gal-1 via the intranasal pathway.

Here, we investigated the consequences of reducing Gal-1 in the TME during the GBM progression on both myeloid and lymphoid compartments of the immune system. Moreover, we evaluated the effect of Gal-1 siRNA therapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy or immunotherapy using DC vaccination and PD-1 blockade on survival of glioma bearing mice. The relevance of our findings were confirmed by the comparison of the Gal-1 knock-down signatures in our GBM model with GBM patients data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Our findings identify Gal-1 as a key regulator of the TME that drives resistance towards conventional chemotherapy and explorative immunotherapy. Nose-to-brain delivery to modulate the TME is an underexplored treatment modality and beholds great promise for GBM patients, especially when combined with chemo- and immunotherapy.

Results

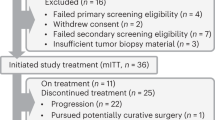

siGal-1 treatment improves survival in GL261 tumor bearing mice by altering the tumor micro-environment

To confirm our previous findings, we first verified the reduction of Gal-1 after siGal-1 administration (Supp. Fig. 1). Gal-1 is reduced whithin the tumor micro-environment by about 40%. In previously published results we observed that reducing gal-1 expression can inhibit the migration and/or proliferation pattern of GL261 murine GBM cells in vitro 26. Stimulated by the existing literature on siGal-1 in GBM, we investigated possible survival benefits in GL261 tumor bearing mice. First, we asked whether intranasal siGal-1 as monotherapy could improve survival (+siRNA, Fig. 1A). We observed a significant shift in survival when siGal-1 loaded chitosan nanoparticles were administered during GBM progression. A small shift of 2.5 days in median survival, and more importantly, about 20% long-term survival was induced. Scrambled siRNA incorporated in chitosan nanoparticles or empty chitosan nanoparticles (+scrambled siRNA and -siRNA, Fig. 1A) had no effect on survival. To further delineate the consequences of siGal-1 treatment, we hypothesized that the prolonged survival could be explained either by a direct decreased proliferation of GL261 tumor cells, or by complementary TME re-arrangement. We first quantified Ki67+ staining to measure tumor proliferation. Proliferation was significantly decreased during siGal-1 treatment, while scrambled siRNA loaded chitosan nanoparticles had no effect on GL261 (Fig. 1B, representative pictures Supp Fig. 2). Of note, the inhibitory effect was already pronounced at day 12 post tumor inoculation, indicating a rapid delivery and onset of siGal-1. Caspase3 staining revealed no changes in apoptosis (Supp Fig. 3). To analyse the cellular composition of GL261 TME, a thorough examination of the macrophage populations was performed (Fig. 1C). Macrophages are one of the most abundant cell types present in the TME of GBM. They can be polarized as either M1 (MHCIIhigh) or M2 (MRChigh) corresponding to pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory phenotypes, respectively27. Gal-1 siRNA treatment induced a shift in these macrophage phenotypes: reduction of Gal-1 did not affect the total pool of macrophages, but effectively reduced the transition from M1 to M2 polarization (Fig. 1D). Scrambled siRNA did not affect macrophage polarization.

siGal-1 monotherapy in GL261 tumor bearing mice elicits a survival benefit, and a re-arrangement of tumor micro-environment. Mice were inoculated with 0.5 × 106 GL261 cells which induce a lethal GBM after 15–20 days. (A) Survvial analysis of mice which were left untreated (clear dots), treated with siGal-1 on day 4, 8, 12 and 15 after tumor inoculation (red squares), or treated with empty nanoparticles (without siRNA, black dots) or treated with scrambled siRNA loaded chitosan nanoparticles (scrambled siRNA, black triangles). (B) Quantification of proliferation assay measured by Ki67+ staining. Monotherapy siGal-1 revealed a significant Ki67+ proliferation decrease in GL261 gliomas, in early and late stage (early stage = day 12 after tumor inoculation; 2 administrations, at day 4 and 8/at late stage GBM = day 20 after tumor inoculation, with 4 administrations at day 4, 8, 12 and 15), as compared to controls, untreated or scrambled siRNA loaded chitosan nanoparticles (n = 4/group, *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001). (C) Immunofluorescence pictures of TME, stained for total macrophages (F4/80+), M1 macrophages (MHCII+) and M2 macrophages (MRC1+), obtained from untreated control mice, scrambled siRNA loaded chitosan nanoparticles treated mice, or siGal1 treated mice. These pictures indicate that the total amount of macrophages in the TME is not affected, but merely the polarization of M1 to M2 polarization. MRC1+M2 macrophages are reduced with siGal-1 therapy, as compared to untreated or scrambled siRNA treated mice. (D) Quantification of multiple sections of several mice (n = 4/group), indicates the effect is most pronounced at late stage GBM (day 20 after tumor inoculation, with 4 administrations at day 4, 8, 12 and 15), whereas in early stage (day 12 after tumor inoculation; 2 administrations, at day 4 and 8) these differences were less pronounced. Black bars represent treated mice, white bars are untreated controls, and gray bars are treated with scrambled siRNA loaded chitosan nanoparticles; groups were compared via two way ANOVA, with Bonferroni post test as compared to control and scrambled siRNA (n = 4/group, ***p < 0.001). Scale bar: 75 µm.

siGal-1 treatment modulates myeloid and lymphoid cells during GBM progression

We next assessed whether Gal-1 expression is linked to changes in the myeloid compartment of TME infiltrating leukocytes. Using flow cytometry, we observed a reduction in CD11b+ leukocytes from 37 to 28% in response to siGal-1 intranasal administration (Fig. 2A; gating strategy Supp Fig. 4). Further subtyping revealed that this reduction was mainly caused by a reduction in immune suppressive monocytic myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) defined as Ly6C+CD11b+ leukocytes from 26 to 20%. The percentage of granulocytic MDSCs (Ly6G+CD11b+) appeared unaffected. Besides MDSCs in the TME, also macrophages can exert immune suppressive functions. As described above, macrophages can be subtyped in M1 (MHCIIhigh, MRC−) or M2 (MHCIIlow,MRC+) of which the latter are known to reduce inflammation and negatively affect the prognosis in GBM. Flow cytometry analysis confirmed that the reduction of Gal-1 promotes the M1 phenotype, and prevents the M2 phenotype (Fig. 2A).

siGal-1 alleviates immune suppression and induces immune activation during GBM progression. Flow cytometry was performed on isolated mononuclear brain infiltrating cells of mice that were left untreated, or treated with siGal-1 on day 4, 8, 12 and 15 after tumor inoculation, and brains were isolated at day 20. Different stainings assess several cell populations with (A) the myeloid cells, with monocytes as gated by ZY−, CD45+, CD11b+; monocytic MDSCs as ZY−, CD45+, CD11b+, Ly6C+; M1 macrophage phenotype as CD45+, CD11b+, ZY−, MRC−, MHCIIhigh; M2 macrophage phenotype as CD45+, CD11b+, ZY−, MRC+, MHCIIlow. (B) The lymphoid cells with leukocytes, as single cells, ZY−, CD45+; lymphocytes as single cells, ZY−, CD45+, CD3+, CD4 lymphoctyes as single cells, ZY−, CD45+, CD3+, CD4+; Th1 as single cells, ZY−, CD45+, CD3+, CD4+, IFNγ+ gated to CD45+; CD8 lymphocytes as single cells, ZY−, CD45+, CD3+, CD8+; CTL as single cells, ZY−, CD45+, CD3+, CD8+, IFNγ+ gated to CD45; Tregs, as gated by single cells, ZY−, CD45+, CD3+, CD4+, FoxP3+; (C) the ratio immune activation to immune suppression was calculated for Th1 (IFNγ+CD4+CD3+CD45+ZY−) and (D) CTL (IFNγ+CD8+CD3+CD45+ZY−), as compared to Treg (FoxP3+CD4+CD3+CD45+). White bars represent the siGal-1 treated mice, black bars are control tumor bearing mice and groups were compared with unpaired t-test (n = 5/10 per group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

As the immune suppressive myeloid cells compartment was altered by Gal-1 siRNA treatment, we analysed the lymphoid counterpart and monitored the regulatory T cell population (Treg). Both at the mRNA and protein level, we detected a decrease of FoxP3+ cells, a Treg specific transcription factor (Fig. 2B + Supp Fig. 5; gating strategy Supp Fig. 6). Together these data indicate a general reduction of immunosuppression in GBM, in both the innate and adaptive arm of immunity, when gal-1 expression is diminished.

On the other side of the spectrum, we have investigated the immune stimulatory mediators in GBM. Overall, we found a decrease in leukocytes (CD45 + viable cells; Fig. 2B; gating strategy Supp Fig. 7), which we attribute to the decrease in overall myeloid MDSCs. Further co-staining revealed a significant increase in CD3+ lymphocytes (Fig. 2B). Specifically, we found a general increase in T helper lymphocytes (Th, CD4+CD3+lymphocytes), and cytotoxic T cells (CTL, CD8+CD3+lymphocytes). These cells appeared not only increased in number, but also in function, as measured by their interferon–gamma (IFNγ) production, indicated as Th1 (CD4+) and CTL (CD8+) lymphocytes relative to the total amount of leukocytes (Fig. 2B). As we observed an increase in Th1 and CTL response, and a decrease in Treg population, the ratio of immune activation to immune suppression was clearly shifted in favor of activation (Fig. 2C+D). Taken together, these data indicate that siGal-1 treatment can induce an alleviation from the immune suppression, while increasing the immune activation.

siGal-1 therapy synergizes with TMZ and PD-1 blocking

To our understanding, siGal-1 treatment should be applied as an adjuvant therapy that synergizes with existing treatment schedules. As mentioned before, reducing gal-1 expression has been shown to improve the efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs such as TMZ in GBM bearing mice17. Also in our GL261 model, after three administrations of 40 mg/kg, we observed a significant median survival shift for glioma bearing mice, from 19 days in untreated mice, to 32 days in TMZ treated mice (Fig. 3A). Combining the intranasal siGal-1 administration and per os TMZ administration resulted in a synergistic survival benefit. In the combination therapy, the median survival increased from 32 days in TMZ treated mice, to 53 days in siGal-1 and TMZ treated mice. We also observed a long-term survival of 40% after combination therapy, compared to about 20% under monotherapy. These results indicate that reducing gal-1 expression could be applied as an adjuvant treatment modality to TMZ administration.

Survival benefit of siGal-1 in combination with chemo- and immunotherapy. Mice were inoculated with 0.5 × 106 GL261 cells which induce a lethal GBM after 15–20 days. Combination strategy with (A) TMZ was organized by siGal-1 administration at day 2, 4, 7 and 11 after tumor inoculation prior to TMZ administration at day 8, 11 and 15, at a dose of 40 mg/kg. For combination with immunotherapy, DC vaccination (B) and PD-1 blocking (C) were included. In (B), mice received monotherapy siGal-1 as described in Fig. 1A (open red squares), prophylactic DC vaccination at day −14 and −7 before tumor inoculation (200 µg lysate/million DCs, IP, black dots), or the combination of DC vaccination and siGal-1 (closed red squares). In (C), mice received anti-PD-1 mAb at day 7 and 12 after tumor inoculation (100 µg/day, IP, black dots) or the combination of PD-1 blocking and siGal-1 (closed red squares). Curves were compared by Log-Rank survival analysis. (n = as indicated, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001). (D) Based on median survival data (from Fig. 3A,B and C), the calculations for antagonistic effect, additive effect and synergistic effect were carried out based on the Robert Clark Equations29; where A = response to treatment 1 (=siGal-1), B = response to treatment 2 (=TMZ, DCvacc or anti-PD-1), AB = combination groups and C = response to no treatment (=control).

Given that reducing gal-1 expression alone could shift the balance from immune suppression to activation, resulting in a modest survival benefit (Fig. 1A), combining siGal-1 with other immunotherapies seemed appealing. Therefore we started with a prophylactic vaccination model established in our facilities28. Mice were vaccinated two weeks before tumor inoculation with lysate pulsed DC vaccines which results in strong anti-tumoral immunity as indicated by the survival benefit of 20.5 days in untreated mice, to 42 days in DC vaccine treated mice (Fig. 3B). We observed that combining DC vaccine with siGal-1 further pushed the significance level, and increased the median survival to 53 days with about 30% long-term survival. No statistical difference was observed between DC vaccine and the combination therapy, largely attributed to the heterogeneous effect of DC vaccine. As a second immunotherapy approach, we tested immune checkpoint blockade by means of PD-1 blocking in established brain tumors. Intraperitoneal injection of anti-PD-1 antibody increased the survival from 17.5 days in untreated mice, to 30 days in anti-PD-1 treated mice (Fig. 3C). Concomitant intranasal administration of siGal-1 profoundly improved the therapeutic effect of anti-PD-1 administration, resulting in a median survival of 51.5 days and about 20% long term survival.

To quantify the effect of the combination regimens with siGal-1, TMZ, DC vaccination and PD-1 blocking, we used the Robert Clarke Equations, that can discriminate between additive or synergistic effects (Fig. 3D)29. Calculation revealed an additive effect of DC vaccination and siGal-1 combination, and a synergistic effect of siGal-1 with either TMZ treatment or with PD-1 blocking antibody injection.

We conclude from these data that siGal-1 therapy is effective in a rational combination with chemo- and immunotherapy.

Mechanistic insight into synergistic effects of siGal-1

We observed a small survival benefit for mice that received monotherapy siGal-1 (Fig. 1A) and a strong synergistic effect of reducing gal-1 expression in combination with chemo and immunotherapy. Therefore, we tried to elucidate the underlying mechanisms driving the synergy. We noticed that blood vessels in the tumor bearing mice that were treated with siGal-1 appeared less dilated and tortuous than in untreated mice (Fig. 4A). In untreated control mice, the tumor vasculature typically features dilated and non functional vessels whereas gal-1 targeting therapy significantly normalizes vessel caliber (Fig. 4B). Scrambled siRNA however does not normalize the vasculature in GBM (compare vessels in Fig. 1C). Chaotic TME blood vessels typically result in a poor tissue perfusion. We therefore hypothesized that TMZ could reach a larger tumor area if vessels were normalized to some extent30. To observe the distribution pattern of TMZ, we performed immunohistochemistry labelling phospho-H2aX to highlight double strand break DNA damage (Fig. 4C and D). Equal dose of TMZ induced more widespread DNA damage after pre-treatment with siGal-1, consistent with the observed normalization of the tumour vasculature.

Mechanistic insights explaining synergistic effects of siGal-1 with chemo and immunotherapy. Mice were inoculated with 0.5 × 106 GL261 cells which induce a lethal GBM after 15–20 days. (A) Mice were left untreated (left panel), treated with siGal-1 on day 4, 8, 12 and 15 after tumor inoculation (right panel), and stained for GLUT-1 (red), which stains vasculature. (B) Quantification revealed signficantly enlarged vasculature in untreated mice. (n = 5/group, **p < 0.01). (C) TMZ induced DNA damage was measured by phospho-H2AX staining (green), which (D) indicated a significant higher DNA damage pattern if mice were pre-treated with siGal-1. (n = 3/4/group, **p < 0.01). (E) Analysis of brain infiltrating lymphocytes during anti-PD-1 therapy (at day 7 and 12 after tumor inoculation, 100 µg/day), at day 18 post tumor inoculation, revealed a significant decrease of PD-1 expression on CD4+ (black bars) and CD8+ (gray bars) lymphocytes. In (F) the ratio immune activation to immune suppression was calculated for Th1 (IFNγ+CD4+CD3+CD45+ZY−) and CTL (G) (IFNγ+CD8+CD3+CD45+ZY−), as compared to Treg (FoxP3+CD4+CD3+CD45+). (n = 5/group, *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01). Scale bar: A. 100 µm; C. 250 µm.

To elucidate the synergy between siGal-1 and anti-PD1 therapy, we performed flow cytometry analysis of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. We observed that anti-PD1 therapy effectively reduced the expression of PD-1 on CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes in the glioma TME (Fig. 4E), but no additional effects of combined siGal-1 treatment. Next, we observed that the ratio between Th1 response and Treg, or CTL and Treg, was increased upon anti-PD-1 therapy, and even more pronounced in combination therapy (Fig. 4F and G). These data, together with the survival benefits (Fig. 3C), indicate that anti-PD1 therapy by itself can stimulate the immune activation, and also that siGal-1 therapy can further increase the immune stimulation.

LGALS1 facilitates immunosuppressive T cell milieu in glioblastoma tumor tissue

Our preclinical results indicated that Gal-1 promotes immunosuppression within the GBM TME and as such, targeting it helps shift the TME towards an anti-tumorigenic Th1/CTL-based immune contexture. Therefore, we wanted to validate whether Gal-1 (coded by the gene LGALS1) also facilitates immunosuppression of T cells within the GBM TME of human patients. We deemed such analysis crucial for translational positoning and prioritization of this siGal-1 therapy for GBM patients in the near future.

High-powered genetic analysis of human tumor-associated T lymphocytes (TILs) in publicly available big-datasets like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) can be achieved through the emerging technique of using (pre-established) T cell-specific gene signatures or metagenes31,32,33. To this end, we utilized recently established T cell-specific metagenes tailored for human GBM12 and first estimated GBM patient survival based on a ratio of Th1-to-Treg and CTL-to-Treg to estimate the prognostic impact of a Th1/CTL vs. Treg based immune contexture.

In line with previous observations12, TCGA GBM patients exhibiting higher expression of Th1/Treg metagene-ratio (i.e. more Th1 expression and less Treg expression) (Fig. 5A) and CTL/Treg metagene-ratio (Fig. 5B), had prolonged overall survival (OS) compared to corresponding low expression groups, as indicated by hazard ratios (HRs; 0.83 (0.66–1.05) for Th1/Treg metagene-ratio and 0.81 (0.64–1.03) for CTL/Treg metagene-ratio). This reiterates the importance of a Th1/CTL-based immune contexture over a Treg-based immune contexture for cancer patients12, 34.

Analysis of association between T cell-associated genetic signatures and LGALS1 in human glioblastoma (GBM) patients. (A) The ratio of genetic signatures or metagenes specific for Th1 and Treg was used to stratify the The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) GBM patients into “high Th1/Treg ratio” (red) or “low Th1/Treg ratio” groups; followed by Kaplan-Meier plotting of patient’s overall survival versus follow-up duration in days. (B) The ratio of genetic signatures or metagenes specific for CTLs and Treg was used to stratify the TCGA GBM patients into “high CTL/Treg ratio” (red) or “low CTL/Treg ratio” groups; followed by Kaplan-Meier plotting of patient’s overall survival versus follow-up duration in days. (C) The differential expression of LGALS1 was used to stratify the TCGA GBM patients into “high expression” (red) or “low expression” groups; followed by Kaplan-Meier plotting of patient’s overall survival versus follow-up duration in days. In A–C graphs, log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test p-values and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence interval (in paranthesis) are displayed. Alternatively, a Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to assess the overall association between LGALS1 expression and overall expression of either Th1/Treg ratio (D) or CTL/Treg ratio (E).

Interestingly, GBM patients exhibiting high expression of GBM-associated LGALS1 tended to show subtantially reduced OS compared to patients possessing LGALS1 Low GBM tumors (Fig. 5C). In line with previous studies13, 35, 36, these findings confirm (at the TCGA-level) our observation of Gal-1 being a pro-tumorigenic factor. However, Gal-1 has several functions within the tumor, not only in glioma cells but also in stromal or immune cells. With respect to our preclinical data and the clinical analysis above, it was necessary to ascertain the exact association of LGALS1 with Th1/Treg and CTL/Treg ratios. Interestingly, LGALS1 gene expression showed a highly significant negative correlation with the Th1/Treg (Fig. 5D) and CTL/Treg (Fig. 5E) metagene-ratios within the TCGA GBM cohorts. These results would be in line with a role for higher LGALS1 expression facilitating the accumulation of Treg over Th1/CTL in GBM.

In conclusion, our TCGA GBM clinical data analysis suggests that LGALS1 facilitates the maintenance of a immunosuppressive Treg-based tumoral environment.

Discussion

Understanding the cellular and molecular dynamics in the TME of malignancies such as GBM is a prerequisite for the development of effective non-invasive therapies. Our current work focused on Gal-1 as an important driver for the inherent resistance against chemo- and immunotherapy in GBM biology. Specifically, we demonstrate that, by using the nose-to-brain transport, we are able to suppress gal-1 expression in the TME, which results in a shift from immune suppression to immune activation. Our intranasal approach to block gal-1 expression in GBM confirms the previous benefitial findings that were however obtained by much more invasive approaches not translatable to the clinic. Moreover, we could demonstrate synergistic effects with novel immunotherapeutic agents as PD-1 blocking agents, which gives additional arguments why nose-to-brain transport to reduce gal-1 expression could represent a valuable adjuvant therapy. In the present study, we explored the potential of chitosan nanoparticles to promote the nose-to-brain delivery. In part, these particles were selected due to the ease of manufacturing, the gentle production process and the proven transport into the central nervous system. In a recent literature report, chitosan coated lipid nanocapsules have been proven to effectively silence Gal-1 and EGFR in GBM, which also sensitizes GBM to TMZ treatment37. To this end, both lipid-based and polymeric based formulations can have beneficial effects, and are demonstrated to posses effective RNAi delivery efficiency.

In a syngenic, orthotopic murine model for GBM, we provide evidence that reducing gal-1 expression induces a significant survival benefit. We observe a shift in median survival, and a long term survival induction of 20%. Especially the induction of long term survivors is intriguing, which coincided with remarkable changes in the microenvironment. Moreover, we demonstrate a decreased Ki67 proliferation in siGal-1 treated GL261 gliomas. In a previous report, we demonstrated that we are able to decrease gal-1 expression in the TME by 50% as measured by western blot analysis26. Despite this robust decrease of Gal-1, the survival benefit in monotherapy is only modest, which already implies that siGal-1 should be considered as a sensitization tool to increase the efficiency of existing treatment modalities. To analyse the cell composition of the GBM TME, we dissected the macrophage population during GBM progression. We demonstrate the inhibition of polarization from M1 macrophages to M2 macrophages during GBM progression, when treated with siGal-1. Activation of the M2 phenotype has been shown to worsen the prognosis and aggravate disease through secretion of vascular promoting factors such as VEGF-A, and immune suppressive factors such as TGF-β and IL-10. This macrophage population relocates around TME associated vessels to form perivascular cuffs and further drives vascular abnormalities (Mathivet T. et al.; Dynamic stroma reorganization drives blood vessel dysmorphia during glioma progression; under revision). Therefore, a decrease in M2, but also in CD11b monocytes, and specifically the monocytic MDSCs, can already relieve a major fraction of the immune suppressive nature of the TME38. In recent years, it has been suggested that there is an intensive crosstalk between the immune suppressive actors of the myeloid side and of the lymphoid arm of the immune system. We also find a decrease in FoxP3+ Treg cells in the TME when Gal-1 is reduced. Whether this effect is mediated by a myeloid-lymphoid interaction or a direct effect of Gal-1 remains unclear39. The presence of Gal-1 and the recruitment of FoxP3+ Treg cells has already been established in previous reports40, 41. Not only do we find evidence for alleviation of immune suppression upon siGal-1 treatment, but also for promoting immune activation. CD3+ lymphocytes are increased within the TME upon Gal-1 reduction, and more specifically, both Th1 and CTL infiltrate the GBM. It has been demonstrated that GL261 cells upon IFN-γ stimulus, can up regulate MHCI molecules, and thereby are more susceptible to CD8+ mediated destruction12. These findings are in line with the proposed role of Gal-1 that drives apoptosis in activated T cells when reaching the TME42.

In further functional testing of our intranasal siGal-1 approach, we do not consider siGal-1 therapy as a monotherapy, but rather as an adjuvant therapy, which can be combined with chemo- and immunotherapy. Combination therapy of intranasal siGal-1 (at a dose of 1 unit at day 2, 4, 7 and 11) and per os temozolomide (at a dose of 40 mg/kg at day 8, 11 and 15) elicits a significant synergistic survival benefit. The shift in median survival was similar to that described previously, with intratumoral and intraventricular siGal-1 injections17, although in previous studies no long-term survivors were observed, most likely due to the use of nude-mice, and therefore lacking an immune component. This underlines the bio-equivalence of the non-invasive intranasal pathway, in comparison with more aggressive, invasive therapies. We observed that treatment with siGal-1 can reduce the vascular diameter in the TME from 15 µm to 10 µm. Previous reports describe how tumor derived Gal-1 can enhance endothelial function in migration and proliferation potential43, or even complement VEGF signaling44, 45. This reduction can be either attributed to the reduction in M2 (and lack of VEGF-A secreted in the perivascular spaces), or to direct anti-angiogenic effects of siGal-1. Therefore, the pre-treatment with siGal-1 could improve TMZ delivery through better tumor vessel perfusion in the entire TME, thus reaching the tumor mass in toto. We provide a functional experimental read-out in showing aggrevated and widespread DNA damage, which is not necessarily the result of enhanced perfusion, but supports the hypothesis. On the other hand, the reduction of Gal-1 obtained with siGal-1 pre-treatment alters the unfolded protein response to endoplasmatic reticulum stress, increasing thereby the inherent sensitivity of GBM cells to TMZ delivered17. Accordingly, in other, non-reported experiments, where siGal-1 therapy was administered concomitantly or later in the dosing schedule, we did not observe this synergy. This dose regimen optimization supports the hypothesis that siGal-1 should be delivered prior to TMZ administration. Assessment of the aggravated DNA damage induced by alkylating chemotherapy in the combination demonstrates that more tumor tissue is affected by administration of TMZ, as pointed out by the increase of phospho-H2aX histone complexes. This increase results in G2/M arrest46. Interestingly, TMZ is also reported to have anti-angiogenic properties, which might attribute to the observed synergistic effects between siGal-1 and TMZ47. In this study, TMZ was discovered to impair angiogenic processes, leading to strong survival benefits of human xenograft models when combined with bevacizumab. Interestingly, in a recent clinical trial report, TMZ showed unexpected immune-modulating activity48. Low-dose regimen TMZ could actively suppress regulatory T cells patients with advanced melanoma. We therefore speculate that siGal-1 and TMZ can work together to actively decrease the regulatory T cell population, and prevent further tumor progression. Alternative combination treatments can be found in the field of immunotherapy. In a first approach, we tested a DC vaccination strategy developed in our laboratory, as a potent prophylactic immunotherapy in the murine GL261 model. In the tested dosing combination, we could only observe non-significant additive survival benefit upon Gal-1 reduction. However, with immune checkpoint inhibition via PD-1 blockade, combination therapy leads to a synergistic survival benefits in mice with established brain tumors. We also find an increased immune stimulation of lymphocytes in the TME in the combination treatment, as compared to PD-1 blocking alone. Of note, aberrant vasculature in tumors is suggested as a substantial barrier for the extravasation of T cells38. As siGal-1 could efficiently reduce the vascular abnormalities, this could potentially explain the influx of Th1 and CTL. According to Robert Clark Equations, we observed a synergistic effect of combining anti-PD-1 therapy and TMZ therapy with siGal-1, and an additive effect of DC mediated immunotherapy in combination with siGal-1 (Fig. 3D). Adjuvant therapies such as siGal-1 therapy might therefore represent valuable approaches to further increase the efficiency of anti-PD-1 and TMZ therapy.

To validate our findings, we correlated the murine data with their human TCGA patient counterpart. Also in human samples, we found a clear correlation between lower Gal-1 and immune activation. Patients with lower Gal-1 had a more favorable Th1/Treg or CTL/Treg balance, which reflects in a better prognosis, as demonstrated by hazard ratios. Murine models have many advantages, but also inherent limitations. By demonstrating the translatability of Gal-1 biology on T cells from murine to human samples, we confirm the potency of Gal-1 as a driver of immune suppression during GBM progression.

In our research, we have elaborated on several key features of GBM tumor progression that are driven by Gal-1 biology. We have addressed proliferation, angiogenic, immunological, and TMZ-resistance properties of GBM after targeting gal-1 expression via intranasal siRNA delivery. This research is a first step to pave the way towards a clinical implementation of the nose-to-brain transport of siGal-1 in the current treatment schedule of GBM patients. To our knowledge, this is the first report where the aforementioned pathway is validated from pharmaceutical development, to biological efficacy in a GBM tumor model. Moreover, as PD-1 blocking is currently being tested in clinical trials for GBM, we provide a method to augment its efficacy via a combination with this transnasal siGal-1.

Materials and Methods

Animals and treatments

International ethical guidelines were followed and approved by the bioethics committee at KU Leuven. Tumor inoculations were performed as described previously26. In brief, 0.5 × 106 GL261 cells were stereotactically injected in the striatum of 8–10 weeks old C57Bl/6 mice (C57BL/6JOlaHsd, Harlan,The Netherlands). GL261 cells were received as a gift from Dr. Eyupoglu, University of Erlangen, Germany. Long term survival was defined as exceeding 3 x median survival of untreated control mice. Intranasal siGal-1 administrations were administered as 8 droplets of 3 µl with a non-adhesive micropipette tip (Eppendorf). Total amount of 1 administration was defined by 48 µg siRNA/dose and chitosan nanoparticles composition as described before26. In brief, chitosan nanoparticles were prepared by ionic gelation of tripolyphosphate and chitosan, while adding siRNA. Consequently, particles were collected by ultracentrifugation at 40000 × g during 3 cycles of 20 min, and freeze-dried with sucrose as lyoprotectant. At the indicated time points, chitosan nanoparticles were administered intranasally, under 3% isoflurane anesthesia. Mice that received intranasal PBS (control) or chitosan nanoparticles, experienced shivers and extensive grooming after anesthesia, followed by a small weight loss (1–2 g) the next day, due to the isoflurane administration of typically about 30 min/mouse. This weight loss quickly recovered, although in the 3th week after tumor inoculation, mice start to loose weight due to tumor burden. Sequences: siGal-1 5′ACCUGUGCCUACACUUCAAdTdT3′) and scrambled siRNA (5′GGAAAUCCCCCAACAGUGAdTdT3′) were purchased from GE Dharmacon.

TMZ administrations were performed as described previously12. In brief, Temodal capsules were opened and dissolved in a phosphate buffer, with an equal amount of L-Histidine, and administered in a total volume of 200 µl by gavage (Schering-Plough, Belgium). For survival experiments mice received 40 mg/kg TMZ at day 8, 11 and 15 post tumor inoculation. For phospho-H2AX assessments, mice received 80 mg/kg TMZ at day 13 and 14 post tumor inoculations, and were sacrificed for immunostainings 4 h after the last administration.

DC vaccinations were performed as described previously28. In brief, 200 µg irradiated lysate was loaded per 1 × 106 immature DCs. Subsequently DCs were pulsed towards mature DCs with LPS, settled for 24 h, and intraperitoneal administered at day 14 and day 7 prior to tumor inoculation. Anti-PD-1 antibodies (RMP1-14) and isotype controls (Rat IgG) were dissolved in saline (Braun, The Netherlands) and intraperitoneal administered at day 7 and 12 post tumor inoculation (100 µg/administration, Epirus Biopharmaceuticals).

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis was performed as described earlier12. In brief, animals were sacrificed by lethal injection of Nembutal at the indicated time points, and perfused with PBS (Lonza, Belgium). Single cell suspensions were obtained after mincing with scalpels and 30′ incubation with DNase (Invitrogen) and CollagenaseD (Roche). Mononuclear cells were separated from debris via Percoll gradient centrifugation (Sigma), and the intermittent layer was washed twice with PBS. Surface stainings were performed with antibodies as mentioned in Table 1.

The intracellular detection of FoxP3 was performed using a FoxP3 staining kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. For intracellular IFN-γ staining, cells were stimulated for 4 h with 100 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate, 1 µg/ml ionomycin and 0.7 µg/ml monensin. Cells were fixed in 1% PFA for 15 min. and resuspend in 0.5% PBS/BSA until acquiring by cytometer (LSRFortessa, BD). Cell population analysis was performed with FlowJo.

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining was performed on mouse brain vibratome sections as described earlier26. Following primary and secondary antibodies are summarized in Table 2. White bars represent 50 µm.

Aqcuisition was performed on Leica SP8 confocal microscope and analyzed via Adobe Photoshop and ImageJ Using a 25x water immersion objective.

Quantitative assessment of vessel diameter was performed by measuring at least 12 vessel diameters in 3 independent pictures per mouse at day 20 post tumor inoculation.

RT-qPCR

mRNA analysis on siRNA treated tumor biopsies were processed as described earlier26.Total RNA was isolated, and PCR reaction was prepared for GAPDH as housekeeping gene, and foxP3 as gene of interest (Forward: ccc agg aaa gac agc aac ctt, Reverse: ttc tca caa cca ggc cac ttg, Taqman Probe: atc cta ccc act gct ggc aaa tgg agt c).

Correlation between T cell-associated genetic signature and LGALS1

The metagene associated with Th1, Treg or CTLs31, 33 were derived from our previously published analysis where GBM-tailored T cell-metagenes were established12. Th1/Treg and CTL/Treg ratios were then generated based on these datasets, using the TCGA GBM Exome sequencing data. The correlation of LGALS1 was analyzed with respect to these Th1/Treg or CTL/Treg metagene-ratios in TCGA GBM patient datasets to generate a (Pearson’s) correlation. Data retrieved from Project Betastasis webplatform.

Prognostic impact of T cell-associated genetic signatures and LGALS1

The differential (exome sequencing-derived) expression levels of Th1-associated metagene12, CTL-associated metagene12 or LGALS1 and associated clinical survival information (overall survival or OS) was retrieved and analyzed for the TCGA GBM patient data-set (n = 349)49, 50 using the Project Betastasis web-platform. These platforms stratified the respective patients on the basis of the median gene expression profile into two risk-groups i.e. high risk or low risk33. The respective patient risk groups were plotted with respect to OS to generate Kaplan-Meier curves using the Graphpad Prism software51. Hazard ratio (and its 95% confidence interval) and log-rank (Mantel-Cox) P values were calculated (statistical significance set at p < 0.05)33. Patients surviving beyond the follow-up thresholds were censored.

References

Lefranc, F. et al. Present and potential future issues in glioblastoma treatment. Expert review of anticancer therapy 6, 719–732, doi:10.1586/14737140.6.5.719 (2006).

Louis, D. N. et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta neuropathologica 131, 803–820, doi:10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1 (2016).

Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 (2011).

Stupp, R. et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. The lancet oncology 10, 459–466, doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7 (2009).

Frosina, G. Limited advances in therapy of glioblastoma trigger re-consideration of research policy. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology, 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.05.013 (2015).

Galluzzi, L. et al. Classification of current anticancer immunotherapies. Oncotarget 5, 12472–12508, doi:10.18632/oncotarget.2998 (2014).

De Vleeschouwer, S. et al. Stratification according to HGG-IMMUNO RPA model predicts outcome in a large group of patients with relapsed malignant glioma treated by adjuvant postoperative dendritic cell vaccination. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy: CII 61, 2105–2112, doi:10.1007/s00262-012-1271-z (2012).

Cao, J. X. et al. Clinical efficacy of tumor antigen-pulsed DC treatment for high-grade glioma patients: evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS One 9, e107173, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107173 (2014).

Van Gool, S. W. Brain Tumor Immunotherapy: What have We Learned so Far? Frontiers in oncology 5, 98, doi:10.3389/fonc.2015.00098 (2015).

Hodges, T. R. et al. Prioritization schema for immunotherapy clinical trials in glioblastoma. Oncoimmunology 5, e1145332, doi:10.1080/2162402X.2016.1145332 (2016).

Mar, N., Desjardins, A. & Vredenburgh, J. J. CCR 20th Anniversary Commentary: Bevacizumab in the Treatment of Glioblastoma–The Progress and the Limitations. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 21, 4248–4250, doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1381 (2015).

Garg, A. D. et al. Dendritic cell vaccines based on immunogenic cell death elicit danger signals and T cell-driven rejection of high-grade glioma. Sci Transl Med 8, 328ra327, doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aae0105 (2016).

Camby, I., Le Mercier, M., Lefranc, F. & Kiss, R. Galectin-1: a small protein with major functions. Glycobiology 16, 137R–157R, doi:10.1093/glycob/cwl025 (2006).

Verschuere, T. et al. Altered galectin-1 serum levels in patients diagnosed with high-grade glioma. Journal of neuro-oncology. doi:10.1007/s11060-013-1201-8 (2013).

Toussaint, L. G. 3rd et al. Galectin-1, a gene preferentially expressed at the tumor margin, promotes glioblastoma cell invasion. Molecular cancer 11, 32, doi:10.1186/1476-4598-11-32 (2012).

Le Mercier, M. et al. Evidence of galectin-1 involvement in glioma chemoresistance. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 229, 172–183, doi:10.1016/j.taap.2008.01.009 (2008).

Le Mercier, M. et al. Knocking down galectin 1 in human hs683 glioblastoma cells impairs both angiogenesis and endoplasmic reticulum stress responses. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology 67, 456–469, doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e318170f892 (2008).

Cox, A. D., Der, C. J. & Philips, M. R. Targeting RAS Membrane Association: Back to the Future for Anti-RAS Drug Discovery? Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 21, 1819–1827, doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3214 (2015).

Verschuere, T. et al. Glioma-derived galectin-1 regulates innate and adaptive antitumor immunity. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer, doi:10.1002/ijc.28426 (2013).

Rubinstein, N. et al. Targeted inhibition of galectin-1 gene expression in tumor cells results in heightened T cell-mediated rejection; A potential mechanism of tumor-immune privilege. Cancer cell 5, 241–251 (2004).

Welsh, J. W., Seyedin, S. N., Cortez, M. A., Maity, A. & Hahn, S. M. Galectin-1 and immune suppression during radiotherapy. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 20, 6230–6232, doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2702 (2014).

van Woensel, M. et al. Formulations for Intranasal Delivery of Pharmacological Agents to Combat Brain Disease: A New Opportunity to Tackle GBM? Cancers (Basel) 5, 1020–1048, doi:10.3390/cancers5031020 (2013).

da Fonseca, C. O. et al. Efficacy of monoterpene perillyl alcohol upon survival rate of patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology 137, 287–293, doi:10.1007/s00432-010-0873-0 (2011).

Craft, S. et al. Intranasal insulin therapy for Alzheimer disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a pilot clinical trial. Archives of neurology 69, 29–38, doi:10.1001/archneurol.2011.233 (2012).

Young, L. J. & Barrett, C. E. Neuroscience. Can oxytocin treat autism? Science 347, 825–826, doi:10.1126/science.aaa8120 (2015).

Van Woensel, M. et al. Development of siRNA-loaded chitosan nanoparticles targeting Galectin-1 for the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme via intranasal administration. Journal of controlled release: official journal of the Controlled Release Society 227, 71–81, doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.02.032 (2016).

Sica, A. & Mantovani, A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. The Journal of clinical investigation 122, 787–795, doi:10.1172/JCI59643 (2012).

Maes, W. et al. DC vaccination with anti-CD25 treatment leads to long-term immunity against experimental glioma. Neuro-oncology 11, 529–542, doi:10.1215/15228517-2009-004 (2009).

Clarke, R. Issues in experimental design and endpoint analysis in the study of experimental cytotoxic agents in vivo in breast cancer and other models. Breast cancer research and treatment 46, 255–278 (1997).

Carmeliet, P. & Jain, R. K. Principles and mechanisms of vessel normalization for cancer and other angiogenic diseases. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 10, 417–427, doi:10.1038/nrd3455 (2011).

Bindea, G. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity 39, 782–795, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.003 (2013).

Gentles, A. J. et al. The prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across human cancers. Nature medicine 21, 938–945, doi:10.1038/nm.3909 (2015).

Garg, A. D., De Ruysscher, D. & Agostinis, P. Immunological metagene signatures derived from immunogenic cancer cell death associate with improved survival of patients with lung, breast or ovarian malignancies: A large-scale meta-analysis. Oncoimmunology 5, e1069938, doi:10.1080/2162402X.2015.1069938 (2016).

Garg, A. D., Romano, E., Rufo, N. & Agostinis, P. Immunogenic versus tolerogenic phagocytosis during anticancer therapy: mechanisms and clinical translation. Cell Death Differ 23, 938–951, doi:10.1038/cdd.2016.5 (2016).

Verschuere, T. et al. Altered galectin-1 serum levels in patients diagnosed with high-grade glioma. Journal of neuro-oncology 115, 9–17, doi:10.1007/s11060-013-1201-8 (2013).

Lefranc, F., Mathieu, V. & Kiss, R. Galectin-1-mediated biochemical controls of melanoma and glioma aggressive behavior. World journal of biological chemistry 2, 193–201, doi:10.4331/wjbc.v2.i9.193 (2011).

Danhier, F., Messaoudi, K., Lemaire, L., Benoit, J. P. & Lagarce, F. Combined anti-Galectin-1 and anti-EGFR siRNA-loaded chitosan-lipid nanocapsules decrease temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma: in vivo evaluation. International journal of pharmaceutics 481, 154–161, doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.01.051 (2015).

Melero, I., Rouzaut, A., Motz, G. T. & Coukos, G. T-cell and NK-cell infiltration into solid tumors: a key limiting factor for efficacious cancer immunotherapy. Cancer discovery 4, 522–526, doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0985 (2014).

Curiel, T. J. et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nature medicine 10, 942–949, doi:10.1038/nm1093nm1093 [pii] (2004).

Rabinovich, G. A. & Toscano, M. A. Turning ‘sweet’ on immunity: galectin-glycan interactions in immune tolerance and inflammation. Nature reviews. Immunology 9, 338–352, doi:10.1038/nri2536 (2009).

Salatino, M., Dalotto-Moreno, T. & Rabinovich, G. A. Thwarting galectin-induced immunosuppression in breast cancer. Oncoimmunology 2, e24077, doi:10.4161/onci.24077 (2013).

Perillo, N. L., Pace, K. E., Seilhamer, J. J. & Baum, L. G. Apoptosis of T cells mediated by galectin-1. Nature 378, 736–739, doi:10.1038/378736a0 (1995).

Thijssen, V. L. et al. Tumor cells secrete galectin-1 to enhance endothelial cell activity. Cancer research 70, 6216–6224, doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4150 (2010).

Croci, D. O. et al. Glycosylation-dependent lectin-receptor interactions preserve angiogenesis in anti-VEGF refractory tumors. Cell 156, 744–758, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.043 (2014).

Croci, D. O. & Rabinovich, G. A. Linking tumor hypoxia with VEGFR2 signaling and compensatory angiogenesis: Glycans make the difference. Oncoimmunology 3, e29380, doi:10.4161/onci.29380 (2014).

Bonner, W. M. et al. GammaH2AX and cancer. Nature reviews. Cancer 8, 957–967, doi:10.1038/nrc2523 (2008).

Mathieu, V. et al. Combining bevacizumab with temozolomide increases the antitumor efficacy of temozolomide in a human glioblastoma orthotopic xenograft model. Neoplasia 10, 1383–1392 (2008).

Ridolfi, L. et al. Low-dose temozolomide before dendritic-cell vaccination reduces (specifically) CD4+CD25++Foxp3+ regulatory T-cells in advanced melanoma patients. Journal of translational medicine 11, 135, doi:10.1186/1479-5876-11-135 (2013).

Brennan, C. W. et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell 155, 462–477, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034 (2013).

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature 455, 1061–1068, doi:10.1038/nature07385 (2008).

Garg, A. D. et al. Resistance to anticancer vaccination effect is controlled by a cancer cell-autonomous phenotype that disrupts immunogenic phagocytic removal. Oncotarget 6, 26841–26860 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank IWT Flanders (SBO; Strategisch Basis Onderzoek – research grant 121206), BBTS Belgian Brain Tumor Support), The Olivia fund (www.olivia.be), the Herman Memorial Research fund (HMRF) and the James E. Kearney Foundation for their funding of this study. RK is a Director of Research with the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FRS-FNRS; Belgium). HG and TM are supported by Stichting Tegen Kanker (STK) and an ERC consolidator grant (REshape 311719).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: M. Van Woensel, T. Mathivet, K. Amighi, S. De Vleeschouwer. Development of methodology: M. Van Woensel, J. Belmans, N. Wauthoz, R. Rosière, R. Kiss, V. Mathieu, A.D. Garg. Acquisition of data: M. Van Woensel, T. Mathivet, J. Belmans, A. D. Garg. Analysis and interpretation of data: M. Van Woensel, T. Mathivet, J. Belmans, N. Wauthoz, K. Amighi, S. De Vleeschouwer. Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: M. Van Woensel, T. Mathivet, N. Wauthoz, R. Rosière, F. Lefranc, V. Mathieu, R. Kiss, H. Gerhardt, J. Belmans, L. Boon, S.W. Van Gool, K. Amighi, S. De Vleeschouwer, P. Agostinis, A. D. Garg. Study supervision: N. Wauthoz, K. Amighi, S. De Vleeschouwer.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

A patent application (GB1519841.9) is initiated by KULeuven(LRD) and ULB(TTO) in agreement.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Woensel, M., Mathivet, T., Wauthoz, N. et al. Sensitization of glioblastoma tumor micro-environment to chemo- and immunotherapy by Galectin-1 intranasal knock-down strategy. Sci Rep 7, 1217 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01279-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01279-1

This article is cited by

-

Current approaches in glioblastoma multiforme immunotherapy

Clinical and Translational Oncology (2024)

-

Prognosis and Immune Landscapes in Glioblastoma Based on Gene-Signature Related to Reactive-Oxygen-Species

NeuroMolecular Medicine (2023)

-

Galectin-1 activates carbonic anhydrase IX and modulates glioma metabolism

Cell Death & Disease (2022)

-

Using nanotechnology to deliver biomolecules from nose to brain — peptides, proteins, monoclonal antibodies and RNA

Drug Delivery and Translational Research (2022)

-

Nanoimmunoengineering strategies in cancer diagnosis and therapy

Clinical and Translational Oncology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.