Abstract

New convenient wet-chemistry synthetic routes have made it possible to explore catalytic activities of a variety of single supported atoms, however, the single supported atoms on inert substrates (e.g. alumina) are limited to adatoms and cations of Pt, Pd, and Ru. Previously, we have found that single supported Pt atoms are remarkable NO oxidation catalysts. In contrast, we report that Pd single atoms are completely inactive for NO oxidation. The diffuse reflectance infra-red spectroscopy (DRIFTS) results show the absence of nitrate formation on catalyst. To explain these results, we explored modified Langmuir-Hinshelwood type pathways that have been proposed for oxidation reactions on single supported atom. In the first pathway, we find that there is energy barrier for the release of NO2 which prevent NO oxidation. In the second pathway, our results show that there is no driving force for the formation of O=N-O-O intermediate or nitrate on single supported Pd atoms. The decomposition of nitrate, if formed, is an endothermic event.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The introduction of automotive catalysts in 1971 ushered in a new era of successful commercialization of supported catalysts on a very large scale1. Since then, advances in emission treatment catalysis have enabled automobile manufactures to meet stringent regulatory requirements for CO, NOx, and hydrocarbon emissions. Typically, automotive catalysts contain platinum dispersed on alumina, and rhodium dispersed on ceria-zirconia. Palladium has been successfully employed to substitute for platinum. Generally, fresh catalysts contain single atoms, rafts, nanoparticles with no defined structure, and well-defined discrete crystalline particles that range from nanoparticles to large particles. The gradual but persistent sintering during use decreases the number of single atoms, rafts, and nanoparticles and increases the number of large particles1, 2.

Reduction of NOx and oxidation of CO and hydrocarbons occurs simultaneously in catalysts that treat emissions from a stoichiometric engine. The catalytic reactions for CO, NOx, and hydrocarbon conversion occur via Langmuir-Hinshelwood (L-H) pathways which require adsorption of reactive gases on metal surfaces leading to redox reactions1, 3. The decrease in metal particle size generally increases catalyst performance4,5,6. Theoretical and experimental studies have shown that sub-nanometer particles are more effective than nanosized particles7,8,9,10,11,12,13. However, this is not the case for NO oxidation which decreases with decrease in particle size. The anomalous behavior of NO is due to oxidation of small metal particles which prevent facile NO adsorption14,15,16,17. Thus, a balance in particle size is necessary to achieve optimum performance from emission treatment catalysts.

The smallest metal “particles” are single supported metal atoms which are also present in fresh catalysts. Until recently, it was unknown whether they participate in catalysis or are mere spectators waiting to be sintered. Recent progress clearly shows that single supported atoms are catalytically active towards a variety of reactions18,19,20. The development of solution methods for the synthesis of supported single atoms facilitated the study of catalytic activity21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. The work from Abbet et al. showed that single Pd atoms supported on an MgO surface are catalytically active for CO oxidation31. Since the conventional L-H pathway is not possible on single supported Pd atoms, a modified L-H pathway, involving the substrate was proposed by the authors. For single supported Pd on γ-alumina, two types of structure have been proposed. The surface Pd adatoms bound to four-fold hollow sites on a (100)-terminated alumina has been described by Lee et al.22 for mesoporous alumina supported Pd while cationic structure has been reported by Datye et al.29 for Pd impregnated on commercial γ-alumina.

We have recently shown that inert substrate supported single Pt-atoms32, 33 are catalytically active for both CO and NO oxidation. Our results also showed that single Pt atoms are as effective as Pt particles for NO oxidation and do not follow the trend of decrease in NO oxidation with decrease in Pt particle size. Intrigued by a recent report from Datye et al.29 that atomic Pd on γ-alumina can oxidize CO effectively at room temperature, we carried out NO oxidation on single Pd atoms supported on θ-alumina. The rationale for employing θ-alumina instead of γ-alumina in preparation of model catalyst has been presented previously32, 33. Although Pd particles are not as effective as Pt particles for NO oxidation34,35,36,37, we were surprised to find no detectable NO oxidation under our experimental conditions. We also carried out in-situ DRIFTS studies to gain insights into NO interaction with single supported Pd atoms. In our previous work on single supported Pt atoms, we found strong nitrate bands (in comparison to alumina substrate only) under NO oxidation conditions. We reasoned that the presence of nitrate peaks, stronger than substrate, could be indicative of NO oxidation. However, the nitrate peaks were weaker on single supported Pd atoms than those on alumina substrate.

The proposed mechanistic pathways for oxidation reactions on single supported atoms are essentially modified L-H pathways and either involve the substrate as an oxygen source or the reaction proceeds with both oxygen and reactive gases adsorbed on the metal atom. For example, CO oxidation in the first pathway occurs via CO adsorption on metal atom which then reacts with oxygen from substrate to eliminate CO2. In the second pathway, CO and oxygen are adsorbed on metal atom and form either O-O-C=O or carbonate intermediate which then eliminates CO2. Most of the known examples of single supported atoms (Pt, Ir, Au) have bene prepared on active substrates such as CeO2 or FeOx and the proposed modified Langmuir-Hinshelwood [L-H] pathways that utilize substrates as oxygen sources have been shown to be energetically favorable21,22,23,24,25,26. The exceptions are the single atoms supported on alumina clusters (e.g. PtAl3O7 −) which are highly reactive towards CO oxidation but follow a molecular pathway where oxygen is supplied by alumina cluster for CO2 formation and then alumina cluster re-oxidizes in oxygen27, 28. Alumina has also been proposed to provide oxygen for CO oxidation reactions over atomic Pd29.

Recent detailed theoretical study of NO oxidation on Pd and other metals explores the role of oxygen-coverage, cluster sizes, metal-oxygen binding strength, and oxygen dissociation36. For Pd, palladium oxide is believed to be active catalyst for NO oxidation38,39,40. However, such a study does not exist for single supported Pd atoms. As such, we explored both pathways, commonly suggested for oxidation on single supported atoms, for NO oxidation on single Pd atoms. First pathway is analogous to the one described by Datye et al.29 for CO oxidation, involves NO adsorption on Pd, and employs alumina as oxygen source. The results show that there is energy barrier for the release of NO2 suggesting that NO oxidation will not be facile. We also explored the second pathway where both NO and oxygen are adsorbed on Pd atom and reaction proceeds via O=N-O-O or NO3 intermediates. We find that there is energy barrier to the formation of O=N-O-O or NO3 intermediates and there is no driving force to release NO2.

Results and Discussion

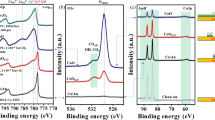

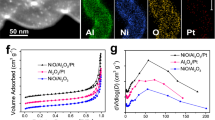

The θ-Al2O3 supported single Pd atom and Pd particles are named Pds/θ-Al2O3 and Pd/θ-Al2O3, respectively. The synthesis of θ-alumina supported Pd samples, Pds/θ-Al2O3 and Pd/θ-Al2O3, was carried out by impregnating θ-alumina powder with tetra-ammine palladium nitrate and subsequent sintering at 700 °C. The Pd loading was kept at 0.2% to obtain mono-disperse palladium single atoms (Pds/θ-Al2O3) and at 2% (Pd/θ-Al2O3) to obtain rafts. HAADF-STEM images of fresh Pds/θ-Al2O3 show single Pd atoms only [Fig. 1, left] and that of Pd/θ-Al2O3 exhibit particles and rafts [Fig. 1, right].

HAADF-STEM images of (I) Pds-θ-alumina and (II) Pd-θ-alumina (right). For Pds-θ-alumina, the inset is an enlargement of the boxed area after additional contrast and brightness was used to make the single atoms more apparent. For Pd-θ-alumina, the inset has been magnified to observe particles and rafts.

NO Oxidation

The NO oxidation for both Pds/θ-Al2O3 and Pd/θ-Al2O3 were carried out under two conditions, 420 ppm NO + 5% O2 [Fig. 2] and 50 ppm NO + 1% O2 [Figure S1]. For comparison, we also carried out NO oxidation on pure θ-alumina. The NO oxidation over Pds/θ-Al2O3 is about same as that over θ-alumina in the 250 to 510 °C inlet gas temperature range. The Pd/θ-Al2O3 catalyst exhibits 17% NO conversion at 354 °C inlet gas temperature, which is about twice that of θ-Al2O3 [Fig. 2]. The NO conversion over Pd/θ-Al2O3 mixed with θ-alumina to reduce Pd loading to 0.2% is 11% at 354 °C gas inlet temperature which is higher than both pure alumina and Pds/θ-Al2O3.

When feed gas contains 50 ppm NO, the NO oxidation decreases to ~11% over Pd/θ-Al2O3 at 350 °C. Both θ-Al2O3 and Pds/θ-Al2O3 show almost identical NO oxidation in 250 to 510 °C inlet gas temperature range [Figure S1]. A comparison of NO oxidation activity over single θ-alumina supported Pt (0.18% Pt/θ-Al2O3 shown as Pts/θ-Al2O3) and Pd (Pds/θ-Al2O3) is shown in Figure S2. The NO oxidation activity over Pds/θ-Al2O3 is identical to that over θ-alumina and significantly less than that over Pts/θ-Al2O3.

The Pds/θ-Al2O3 samples, after exposure to NO oxidation conditions, exhibit predominantly single atoms and ~1 nm clusters [Fig. 3]. No large particles were observed in any of the areas at low magnification. Since we did not observe any detectable NO oxidation on Pds/θ-Al2O3, the very small particles are probably a result of thermal sintering. Since Pd/θ-Al2O3 is active for NO oxidation and NO is unable to induce Pd single atom sintering, the lack of observed NO oxidation on Pds/θ-Al2O3 is due to the inability of Pd single atoms to oxidize NO. The Pd/θ-Al2O3 samples, after exposure to NO oxidation conditions does not undergo dramatic changes [Figure S3].

These experiments clearly show that Pds/θ-Al2O3 is an ineffective NO oxidation catalyst and NO oxidation is not detectable over single supported Pd.

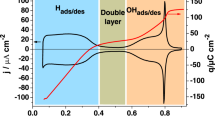

In-Situ Diffuse Reflectance Studies

We carried out in-situ DRIFTS studies to gain insights into NO interaction with single supported Pd atoms. The catalyst sample Pds/θ-Al2O3 was cleaned under oxidizing conditions employing a mixture of 5% oxygen in helium. The IR results for NO oxidation over θ-alumina and Pds/θ-alumina are shown in Fig. 4. At room temperature (~22 °C), the chelating bridging nitrate (N=O stretch at 1610 cm−1 and asymmetric NO2 stretch at 1553 cm−1) can be seen on θ-alumina40. Chelating bidentate nitrate is seen at 1590 cm−1 (N=O stretch) and 1297 cm−1 (NO2 asymmetric stretch) which grows stronger with increasing temperature and become strongest peaks at 350 °C40. Monodentate nitrate peaks (asymmetric NO2 at 1550 cm−1 and symmetric NO2 at 1279 cm−1), on the other hand, become weaker on increasing temperature and cannot be distinguished from chelating nitrate peaks at 350 °C39.

The IR spectra of Pds/θ-alumina during NO oxidation exhibit all the peaks that are seen for θ-alumina although intensity of all nitrate peaks is weaker than that on pure θ-alumina. Since the expected position of nitrate bonded to Pd in monodentate or bidentate mode (1616, 1553, 1312, 1279, 1231 cm−1) is close to those on θ-alumina, an increase in the intensity of nitrate bands would be an indication of formation of nitrates on palladium41. The DRIFTS of Pds/θ-alumina does give indication of Pd-NO− at 1660 cm−1 at 22 °C which decreases in intensity at 252 °C and almost disappears at 350 °C41. These observations are very different from those previously reported for NO oxidation on single supported Pt atoms33. For Pts/θ-alumina the nitrate bands are stronger than those on pure θ-alumina at 252 °C in the absence of O2. Furthermore, the nitrates remain strong bands in the presence of NO + O2 at 300 °C. Thus, the nitrate formation is an essential step during NO oxidation over Pts/θ-alumina but is not observed for Pds/θ-alumina.

The IR spectra of Pd/θ-alumina during NO oxidation exhibits all the peaks that are seen for θ-alumina or Pds/θ-alumina at 22, 252, and 350 °C. Unlike Pds/θ-alumina, there is no indication of NO peaks at 1660 cm−1. The bridging nitrate peaks at 1616 and 1553 cm−1 are present at 22 °C but decrease with increase in temperature and essentially are a weak shoulder at 350 °C. The chelating nitrate peaks at 1590 and 1297 cm−1 increase with increase in temperature to 252 °C but decrease on further increase to 350 °C. Monodentate nitrate peaks at 1553 cm−1 increase in intensity with increase in temperature and can be distinguished from chelating nitrates.

Thus, the differences between inactive single Pd atoms and active Pd particles can be seen in the IR under NO oxidation conditions. First, NO peaks, present in Pd atoms are absent in Pd particles. Second, nitrate peaks are weak for Pd atoms probably due to effective nitrate decomposition but ineffective NO oxidation. Bridging nitrate peaks on active NO particles, on the other hand, decrease while monodentante and chelating nitrate increase with increase in temperature. Interestingly, the increase in nitrate peaks is not comparable to that observed for single Pt atoms33 which are far superior NO oxidation catalysts suggesting nitrate formation is an important step in NO oxidation.

NO Oxidation on Pd/θ-alumina – Theoretical Study

Pd atom on Alumina Surface

A single Pd atom supported on a metal oxide surface can be present as either an adatom bonded to surface oxygen atoms [Fig. 5, I] or a cation replacing one of the surface aluminum atoms [Fig. 5, II]. We have previously reported the optimized structure of a Pd adatom on θ-alumina (010) surface43. Briefly, the Pd adatom occupies a positon above aluminum bonded to two surface oxygen atoms from two adjacent rows of the θ-alumina (010) surface43. The Pd atom is a d10 species with no magnetic moment associated with it. The Pd cation [Fig. 10, II top] resides in the alumina matrix and is bonded to 4 adjacent oxygen atoms with bond distances of 1.9, 2.06, 2.22, and 2.1 Å. The magnetization is associated with Pd and adjacent oxygen atoms bonded to Pd. The projected density of states [PDOS] analysis shows a vacancy in the dx2-y2 orbital suggesting a d9 species [Fig. 5, II bottom].

(I) Pd adatom42 and (II) Pd cation on θ-alumina (010) surface and its PDOS of d-orbitals.

The optimized cationic Pd structure is similar to the one described for Pd cation on γ-alumina (100) surface29 with Pd exhibiting d9 oxidation state. Considering that a d9 Pd is rare and unstable, it is unlikely that it is representative of the single Pd atoms. Furthermore, it is unlikely that either of the two configurations represent single Pd atoms on alumina under ambient atmospheric conditions. In either case, the Pd will react with oxygen to form oxidized species.

The oxygen bonds to Pd adatom in a side-on (η2) mode to give configuration III via an exothermic step (−1.51 eV) [Fig. 6]. Our efforts to optimize structure with monodentate oxygen were unsuccessful as the oxygen gradually moved to bidentate mode of configuration III. For configuration III, the O-O bond distance is 1.39 Å and the projected densities of states (PDOS) show unoccupied 5dxy [Figure S5] suggesting a d8 species. In addition, there is no magnetization associated with configuration III. This bonding mode is identical to the oxygen-bonding mode of Pd in organometallic complexes. For example, the X-ray structures of organometallic compounds, (R3P)2Pd(O2) have been determined previously and show oxygen in a η2 mode42, 44,45,46,47. These complexes exhibit an elongated O-O bond (1.41–1.48 Å) relative to dioxygen (1.21 Å) and superoxide (O2−) (1.33 Å) and approach the value for hydrogen peroxide (1.49 Å).

The Pd cation in configuration II interacts with oxygen in side-on η2-mode also resulting in configuration IV with Pd-O bond distances of 2.06 and 2.04 Å [Fig. 6]. The O-O bond distance is 1.308 Å and the O-Pd-O angle is 37.15°. The Pd now is bonded to six oxygen atoms and the magnetization is centered on the adsorbed oxygen atoms (μtotalO2 0.64). The analysis of PDOS shows partially occupied dyz and dx2-y2 orbitals suggesting a Pd(II) species. Since the EXAFS data fit reported by Datye et al.29 show Pd bonded to four oxygen atoms (coordination number 4) under oxidizing conditions, configuration III might represent atomic Pd under ambient conditions more accurately.

Pathway I. NO oxidation with alumina as an oxygen source

This pathway [Fig. 7] is analogous to the mechanism recently reported for CO oxidation on single Pd atoms supported on γ-alumina and involves alumina as the oxygen source29. The total energy, Pd bond distances to surface oxygen, and magnetizations of intermediate configurations are summarized in Table S1.

This pathway assumes that Pd does not have molecular oxygen associated with it, and the NO oxidation initiates with NO adsorption on the Pd atom in configuration V. The NO adsorption is exothermic (−1.57 eV) and does not significantly impact the Pd bonds to surface oxygens (Table S1). The Pd-N and N-O bond distances are 1.83 and 1.16 Å respectively with a Pd-N-O angle of 172.9°. In this linear bonding mode, NO can be viewed as NO+ which is isoelectronic with CO. The magnetization is primarily associated with nitrogen and oxygen of the NO species. The PDOS analysis of Pd-d-orbitals shows partially filled dxy, dyx, and dx2 orbitals suggesting a d8 oxidation state [Figure S4, V].

The migration of NO in configuration V to form configuration VI results in the bending of NO bond resulting in a Pd-N-O angle of 136.5°. In this bonding mode NO is now NO− and Pd also carries a slight magnetization. Loss of NO2 from configuration VI to configuration VII is an endothermic process. Configuration VII is essentially configuration II with one oxygen vacancy. In this configuration, Pd is bonded to two adjacent oxygen atoms, and the magnetic moment is carried over both oxygen atoms and the Pd atom. PDOS analysis shows partially occupied dyz and consequently a d9 Pd species [Figure S4]. Addition of molecular O2 to configuration VII leads to configuration VIII via an exothermic process. Magnetization in configuration VIII is primarily centered on Pd and an oxygen molecule. The PDOS shows partially occupied d-orbitals with components from all except dx2-y2 [Figure S4].

Addition of NO to configuration VIII via an exothermic process results in configuration IX. The NO bond is in a bent mode (Pd-N-O angle 152.6°) and is formally NO−. The magnetization is distributed over Pd, N-O, and all oxygen atoms bonded to Pd. The analysis of PDOS shows partially occupied dyz and dx2-y2 orbitals [Figure S4]. Finally, the release of NO2 from configuration IX via an exothermic process regenerates configuration II. The energetics of reactions in Fig. 7 are summarized as follows:

This mechanistic pathway suggests that there is a energy barrier to the release of first NO2 (−2.18 eV) although rest of the steps are energetically favorable. This contrasts with CO oxidation pathway, described by Datye et al.29 where CO2 release is an exothermic process.

Pathway II. NO oxidation via NO and O2 adsorption on Pd

Since there is no significant difference between adsorption energies of O2 (−1.51 eV) or NO (−1.44 eV) on the Pd atom [Table S2], the NO oxidation can proceed with either the reaction of oxygen or NO on the Pd atom [Fig. 8]. However, a fresh catalyst can be expected to be oxidized (cf. configuration III) and the NO oxidation will proceed via NO adsorption on oxidized Pd in the first cycle. In subsequent cycles, the configuration I will form which can either react with NO or oxygen.

The NO bonds with the Pd adatom in configuration I via an exothermic reaction (−1.44 eV), and results in configuration X. The Pd-N-O angle is 125.9° suggesting NO is formally NO− and is bonded to Pd in a bent mode. The Pd-N and N-O bond distances are 1.86 and 1.20 Å, respectively. One of the two surface Pd-O bonds breaks to accommodate the NO bonds to Pd. There is no magnetization associated with configuration IV, and PDOS analysis [Figure S5] shows filled d-orbitals. This suggests that Pd retains its zero oxidation state (d10).

Configuration XI can form via exothermic adsorption of NO in configuration III (−1.496 eV) or O2 on configuration X (−1.56 eV). In this configuration, molecular oxygen changes from η2 mode to terminal mode, and NO bonds to Pd in straight mode. Although there is a magnetic moment associated with configuration XI, all of the magnetic moment is localized on O2 (μO2Total, 0.86). One of the two Pd-O (surface) bonds breaks while the other slightly lengthens (0.2 Å). The Pd-N-O angle is 164.8° suggesting NO+ species, and the Pd-N bond is 1.867 Å.

The transformation of configuration XI to configuration XII where nitrosyl forms a nitrate group is an exothermic process (−0.49 eV). The nitrate bonds in monodentate mode with the Pd atom and the Pd-O bond distance is 2.055 Å. The N-O bond where oxygen is bonded to Pd is slightly longer (1.324 Å) than the free N-O bonds of nitrate. The Pd-O surface oxygen bond lengths increase by 0.02 Å as compared with Pd-O surface oxygen bonds when Pd has no substituents. There is a magnetic moment associated with Pd and O from nitrate suggesting a d9 oxidation state for Pd. The PDOS analysis also shows unoccupied 5dxy supporting a d9 oxidation state for Pd [Figure S5]. This structure is similar to nitrate complexes of Pd where nitrate bonds to Pd in monodentate mode48, 49. The three calculated transition states (i–iii) as well as optimized image ii are shown in Fig. 9. The image i optimized to a configuration which is very close to configuration XI in terms of structure and total energy while image iii optimized to a configuration close to configuration XII. The transformation of XI to transition state ii is a slightly endothermic step (0.53 eV) and directly release NO2 via another endothermic step (0.56 eV) to form configuration XIII [Fig. 10]. The transition state ii can form nitrate, XII, via an exothermic step (−1.0 eV). However, there is no driving force to form nitrate since XII is a d9 species which are rare and unstable. Furthermore, the release of NO2 from XII to from XIII is also an endothermic step (1.59 eV). Thus, there is no driving force to either form transition ii or the nitrate species XII and, if formed, the release of NO2 is an endothermic event.

If the reaction does proceed to configuration XII, the release of NO2 will lead to configuration XIII which can react with another molecule of NO to release second molecule of NO2 to complete the catalytic cycle. The details beyond configuration XII are presented in the Supplementary materials. Thus, this pathway shows that there is no driving force for the formation of O=N-O-O intermediate or nitrate on single supported Pd atoms. Furthermore, the decomposition of nitrate, if formed, is an endothermic event.

In conclusion, we have shown that single θ-alumina supported Pd atoms are completely ineffective for NO oxidation in contrast to single supported Pt atoms. The DRIFTS experiments show that nitrate peaks are even weaker than those on alumina under NO oxidation conditions suggesting that nitrate formation plays an important role in NO oxidation. To explain these results, we explored modified Langmuir-Hinshelwood type pathways that have been proposed for oxidation reactions on single supported atom. In the first pathway, we find that there is energy barrier for the release of NO2 which prevent NO oxidation. In the second pathway, our results show that there is no driving force for the formation of O=N-O-O intermediate or nitrate on single supported Pd atoms. The decomposition of nitrate, if formed, is an endothermic event.

Methods

Synthesis of Pds/θ-Al2O3 and Pd/θ-Al2O3

The synthesis of Pds/θ-Al2O3 and Pd/θ-Al2O3 was carried out by an impregnation method as described recently in literature29. The palladium loading for Pds/θ-Al2O3 is 0.2% and that for Pd/θ-Al2O3 is 2%.

Characterization of Catalysts

The samples were examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and a Joel 2200FS FEG 200kv scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) equipped with a CEOS GmbH (Heidelberg, Ger.) hexapole corrector on the probe-forming lenses. High-angle annular dark-field (HA-ADF) images showing single Pd atoms at a nominal resolution of 0.07 nm were collected at a 26.5 mr incidence semi-angle, using a detector having a 110 mr inner semi-angle.

NO oxidation

NO oxidation experiments were carried out in two reactors. The GHSV was kept constant at 51.4 k h−1 for all tests. The feed gas (total flow 3.0 litres/min) composition was 50 ppm NO, 1% O2, and balance N2. The second set of experiments were carried out on a previously reported reactor that we employed to study NO oxidation on single supported Pt atoms33 to directly compare NO oxidation activity of single supported Pt and Pd. Briefly, the powder catalyst samples were loaded in a U-tube quartz reactor between two quartz wool plugs. To keep a constant gas hourly space velocity (GHSV) of ~55.5 k h−1, the palladium catalysts were mixed with blank θ-Al2O3 to provide 120 mg test samples (0.108 mL) for all tests. The feed gas composition was 50 ppm NO, 1% O2 and Ar as a balance. The catalysts were heated to 120 °C under Ar before the NO + O2 reaction gas was introduced and the reactor was further heated to the evaluation temperatures. Each sample was studied sequentially at the following catalyst bed set points: 270, 320, 420, and 520 °C. The catalyst was held at the set point and allowed to stabilize for ~70 min before the NOX concentration was averaged over 5 min. The analyzer was switched to NO mode and given 1–2 minutes to stabilize, and then the NO concentration was averaged over the next 5 min. The NO oxidation activity was calculated as (NOx − NO)/NOx.

Infrared Study NO Adsorption

The detailed methods for NO oxidation by in situ diffuse reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (DRIFTS) have been described previously34, 35. In summary, a Nicolet Nexus 670 spectrometer fitted with a MCT detector cooled with liquid nitrogen was used for recording spectra. The system is equipped with an in-situ chamber (HC-900, Pike Technologies) with a capability to heat samples to 900 °C. The NO oxidation samples were cleaned at 350 °C in a 5% O2 in helium. Samples were then cooled to experiment temperature under a flow of 5% O2 in helium. The NO oxidation experiments were carried out at 25, 250, and 350 °C by flowing a NO (2% NO in Ar, 5 mL/min) and O2 (5% O2 in He, 20 mL/min) mixture over the cleaned sample for 5 minutes followed by 5 minutes of O2 purging.

Computational Method

The total energy calculations, based on ab initio DFT, were carried out employing the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP)50. A generalized gradient approximation (GGA) in the Perdew-Wang-91 form was employed for the electron exchange and correlation potential51, 52. The projector-augmented wave (PAW) approach for describing electronic core states was used to solve Kohn-Sham equations52, 53. The plane wave basis set was truncated at a kinetic energy cutoff of 500 eV. A Gaussian smearing function with a width of 0.05 eV was applied near Fermi levels. Ionic relaxations were considered converged when the forces on the ions were <0.03 eV/Å. We have previously described the details of construction of (010) alumina surface49. From bulk optimized θ-alumina, a 180-atom charge neutral 2 × 4 supercell was constructed49. The slabs were separated by a 15 Å vacuum to minimize spurious interaction by periodic images. A 4 × 1 × 4 Monkhorst-Pack mesh was used for surface calculations. Nudged elastic band method was employed to find transition states54,55,56.

References

Heck, R. M., Farrauto, R. J., Gulati, S. T. Catalytic Air Pollution Control, Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, 2009)

Narula, C. K. et al. Catalysis by Design – Theoretical and Experimental Studies of Model Catalysts. SAE 2007-01-1018.

Langmuir, I. The Mechanism of the Catalytic Action of Platinum in the Reactions 2CO + O2 = 2CO2 and 2H2 + O2 = 2H2O. Trans. Faraday Soc 17, 621 (1921).

Haruta, M., Kobayashi, T., Sano, H. & Yamada, N. Novel Gold Catalysts for the Oxidation of Carbon Monoxide at a Temperature far Below 0 °C. Chem. Lett. 16, 405–408 (1987).

Somorjai, G. A. & Park, J. Y. Molecular Surface Chemistry by Metal Single Crystals and Nanoparticles from Vacuum to High Pressure. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 2155–2162 (2008).

Crespo-Quesada, M., Yarulin, A., Jin, M., Xia, Y. & Kiwi-Minsker, L. Structure Sensitivity of Alkynol Hydrogenation on Shape- and Size-Controlled Palladium Nanocrystals: Which Sites Are Most Active and Selective? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 12787–12794 (2011).

Herzing, A. A., Kiely, C. J., Carley, A. F., Landon, P. & Hutchings, G. J. Identification of Active Gold Nanoclusters on Iron Oxide Supports for CO Oxidation. Science 321, 1331–1335 (2008).

Lin, J. et al. Design of a Highly Active Ir/Fe(OH)x Catalyst: Versatile Application of Pt-Group Metals for the Preferential Oxidation of Carbon Monoxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 2920–2924 (2012).

Heiz, U., Sanchez, A., Abbet, S. & Schneider, W. D. Catalytic Oxidation of Carbon Monoxide on Monodispersed Platinum Clusters: Each Atom Counts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 121, 3214–3217 (1999).

Lei, Y. et al. Increased Silver Activity for Direct Propylene Epoxidation via Subnanometer Size Effects. Science 328, 224–228 (2010).

Qiao, B., Liu, L., Zhang, J. & Deng, Y. Preparation of highly effective ferric hydroxide supported noble metal catalysts for CO oxidations: From gold to palladium. J. Catal. 261, 241–244 (2009).

Turner, M. et al. Selective oxidation with dioxygen by gold nanoparticle catalysts derived from 55-atom clusters. Nature 454, 981–983 (2008).

Kaden, W. E., Wu, T., Kunkel, W. A., Anderson, S. L. Electronic Structure Controls Reactivity of Size-Selected Pd Clusters Adsorbed on TiO2 Surfaces 2009. 326, 826–829 (2009).

Mulla, S. S. et al. Reaction of NO and O2 to NO2 on Pt: Kinetics and catalyst deactivation. J. Catal. 241, 389–399 (2006).

Smeltz, A. D., Getman, R. B., Schneider, W. F. & Ribeiro, F. H. Coupled theoretical and experimental analysis of surface coverage effects in Pt-catalyzed NO and O2 reaction to NO2 on Pt(111). Catal. Today 136, 84–92 (2008).

Weiss, B. M. & Iglesia, E. NO Oxidation Catalysis on Pt Clusters: Elementary Steps, Structural Requirements, and Synergistic Effects of NO2 Adsorption Sites. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 13331–13340 (2009).

Getman, R. B., Xu, Y. & Schneider, W. F. Thermodynamics of Environment-Dependent Oxygen Chemisorption on Pt(111). J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 9559–9572 (2008).

Yang, X.-F. et al. Single-Atom Catalysts: A New Frontier in Heterogeneous Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 1740–1748 (2013).

Jin, Y. Y., Hao, P. P. & Li, Z. Single atom Catalysis: Concept, Method, and Applications. Progress in Chemistry 27, 1689–1704 (2015).

Liang, S. X., Hao, C. & Shi, Y. T. The Power of Single Atom Catalysis. ChemCatChem 7, 2559–2567 (2015).

Fu, Q., Saltsburg, H. & Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M. Active Nonmetallic Au and Pt Species on Ceria-Based Water-Gas Shift Catalysts. Science 301, 935–938 (2003).

Hackett, S. F. J. et al. High-Activity, Single-Site Mesoporous Pd/Al2O3 Catalysts for Selective Aerobic Oxidation of Allylic Alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 8593–8596 (2007).

Qiao, B. T. et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem 3, 634 (2011).

Lin, J. et al. Remarkable Performance of Ir1/FeOx Single-Atom Catalyst in Water Gas Shift Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 15314–15317 (2013).

Hu, P. et al. Electronic Metal-Support Interactions in Single-Atom Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 3418–3421 (2014).

Duarte, R. B., Krumeich, F. & van Bokhoven, J. A. Structure, Activity, and Stability of Atomically Dispersed Rh in Methane Steam Reforming. ACS Catal 4, 1279–1286 (2014).

Li, X. N., Yuan, Z., Meng, J. H., Li, Z. Y. & He, S. G. Catalytic CO Oxidation on Single Pt-Atom Doped Aluminum Oxide Clusters: Electronegativity-Ladder Effect. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 15414–15420 (2015).

Schwarz, H. Doping Effects in Cluster-Mediated Bond Activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 10090–10100 (2015).

Peterson, E. J. Low-temperature carbon monoxide oxidation catalyzed by regenerable atomically dispersed palladium on alumina. Nature Comm 5, 4885 (2014).

Narula, C. K., DeBusk, M. M. Catalysis on Single Supported Atoms in Catalysis by Materials with Well- Defined Structure (ed. Overbury, S. J., Wu, Z. Academic Press, New York, pp 263, 2015).

Abbet, S., Heiz, U., Hakkinen, H. & Landman, U. CO Oxidation on a Single Pd Atom Supported on Magnesia. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5950 (2001).

Moses-DeBusk, M. et al. CO Oxidation on Supported Single Pt Atoms: Experimental and ab initio Density Functional Studies of CO Interaction with Pt Atom on θ-Al2O3 (010). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 12634–12645 (2013).

Narula, C. K., Allard, L. F., Stocks, G. M. & DeBusk, M. M. Remarkable NO Oxidation on Single Supported Platinum Atoms. Sci. Rep 4, 7238 (2014).

Graham, G. W. et al. Effect of alloy composition on dispersion stability and catalytic activity for NO oxidation over alumina-supported Pt–Pd catalysts. Catal. Lett. 116, 1 (2007).

Su, Y., Kabin, K. S., Harold, M. P. & Amiridis, M. D. Reactor and in situ FTIR studies of Pt/BaO/Al2O3 and Pd/BaO/Al2O3 NOx storage and reduction (NSR). Appl. Catal. B: Environ 71, 207 (2007).

Frey, K., Schmidt, D. J., Wolverton, C. & Schneider, W. F. Implications of coverage-dependent O adsorption for catalytic NO oxidation on the late transition metals. Catal. Sci. Tecnol 4, 4356 (2014).

Captain, D. K. & Amiridis, M. D. In Situ FTIR Studies of the Selective Catalytic Reduction of NO by C3H6 over Pt/Al2O3. J. Catal. 184, 377 (1999).

Weiss, B. M. & Iglesia, E. Mechanism and site requirements for NO oxidation on Pd catalysts. J. Catal. 272, 74–81 (2010).

Jelic, J., Reuter, K. & Meyer, R. The Role of Surface Oxides in NOx Storage Reduction Catalysts. Chem. Cat. Chem 2, 658 (2010).

Toops, T. J., Smith, D. B., Epling, W. S., Parks, J. E. & Partridge, W. P. Quantified NOx adsorption on Pt/K/gamma-Al2O3 and the effects of CO2 and H2O. Appl. Catal. B 58, 255–264 (2005).

Chilukoti, S., Gao, F., Anderson, B. G., Niemantsverdriet, J. W. H. & Garland, M. Pure component spectral analysis of surface adsorbed species measured under real conditions. BTEM-DRIFTS study of CO and NO reaction over a Pd/γ-Al2O3 catalyst. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 5510–552 (2008).

Yamashita, M., Goto, K. & Kawashima, T. Fixation of Both O2 and CO2 from Air by a Crystalline Palladium Complex Bearing N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands. J Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 7294 (2005).

Narula, C. K. & Stocks, G. M. Ab Initio Density Functional Calculations of Adsorption of Transition Metal Atoms on θ-Al2O3 (010) Surface. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 5628 (2012).

Yoshida, T. Reversible dioxygen Palladium Complex, PdO2[PPh(t-Bu)2]2 and Irreversible Platinum Analogue, PtO2[PPh(t-Bu)2]2. Crystal and Molecular Structures and the Inter-ligand Angle Effect. Nouv J Chim 3, 761 (1979).

Adjabeng, G. et al. Palladium Complexes of 1,3,5,7-Tetramethyl-2,4,8-trioxa-6-phenyl-6-phosphaadamantane: Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Use in the Suzuki and Sonogashira Reactions and the α-Arylation of Ketones. J. Org. Chem. 69, 5082 (2004).

Konnick, M. M., Guzei, I. A. & Stahl, S. S. Characterization of Peroxo and Hydroperoxo Intermediates in the Aerobic Oxidation of N-Heterocyclic-Carbene-Coordinated Palladium(0). J Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 10212 (2004).

Aboelella, N. W. Mixed metal bis(µ-oxo) complexed with [CuM(µ-O)2]n+ (M=Ni(III) or Pd(II)) Cores. Chem. Comm. 1716–1717 (2004).

Khranenko, S. P., Baidina, I. A. & Gromilov, S. A. Crystal structure refinement for trans-[Pd(NO3)2(H2O)2]. J Struct. Chem 48, 1152 (2007).

Castan, P., Jaud, J., Wimmerm, S. & Wimmer, F. B. Aqueous Chemistry of Platinum and Palladium Complexes. Synthesis and Crystal Structure of a Palladium(II) aqua Complex with a Cyclometallated Ligand: [PdL(H2O)(ONO2)]ClO4.H2O (L=1-Methyl-2-2′-bipyridin-3-ylium). J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1155 (1991).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. J. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P. & Wang, Y. Accurate and simple analytic representation of the electron-gas correlation energy. Phys. Rev. B 45, 13244–13249 (1992).

Perdew, J. P. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: Applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. C. Phys. Rev. B 46, 6671–6687 (1992).

Mills, G., Jonsson, H. & Schenter, G. K. Reversible work transition state theory: application to dissociative adsorption of hydrogen. Surface Science 324, 305 (1995).

Jonsson, H., Mills, G. & Jacobsen, K. W. Nudged Elastic Band Method for Finding Minimum Energy Paths of Transitions, in ‘Classical and Quantum Dynamics in Condensed Phase Simulations’, ed. B. J. Berne, G. Ciccotti and D. F. Coker (World Scientific, 1998).

Acknowledgements

The research was sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Vehicle Technologies Office, Propulsion Materials Program (C.K.N., M.M.D. L.F.A.) and Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (G.M.S.) under contract DE-AC05-ooOR22725 with UT-Battelle, LLC. Z.W. Z.W. was supported by the Center for Understanding and Control of Acid Gas-Induced Evolution of Materials for Energy (UNCAGE-ME), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences. The in-situ IR work was conducted at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, which is a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript and gave approval to the final version of the manuscript. C.N. carried out most of the experimental work, theoretical modelling work in collaboration with G.M.S., and wrote the manuscript. M.D. carried out experiments to compare activity of atomically dispersed Pt and Pd. Z.W. obtained DRIFTS data on the atomically dispersed Pd under NO oxidation conditions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Narula, C.K., Allard, L.F., Moses-DeBusk, M. et al. Single Pd Atoms on θ-Al2O3 (010) Surface do not Catalyze NO Oxidation. Sci Rep 7, 560 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00577-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00577-y

This article is cited by

-

Recent advances in selective catalytic oxidation of nitric oxide (NO-SCO) in emissions with excess oxygen: a review on catalysts and mechanisms

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2021)

-

Single-atom site catalysts for environmental catalysis

Nano Research (2020)

-

Ab Initio Density Functional Calculations and Infra-Red Study of CO Interaction with Pd Atoms on θ-Al2O3 (010) Surface

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.