Abstract

Steep-slope transistors allow to scale down the supply voltage and the energy per computed bit of information as compared to conventional field-effect transistors (FETs), due to their sub-60 mV/decade subthreshold swing at room temperature. Currently pursued approaches to achieve such a subthermionic subthreshold swing consist in alternative carrier injection mechanisms, like quantum mechanical band-to-band tunneling (BTBT) in Tunnel FETs or abrupt phase-change in metal-insulator transition (MIT) devices. The strengths of the BTBT and MIT have been combined in a hybrid device architecture called phase-change tunnel FET (PC-TFET), in which the abrupt MIT in vanadium dioxide (VO2) lowers the subthreshold swing of strained-silicon nanowire TFETs. In this work, we demonstrate that the principle underlying the low swing in the PC-TFET relates to a sub-unity body factor achieved by an internal differential gate voltage amplification. We study the effect of temperature on the switching ratio and the swing of the PC-TFET, reporting values as low as 4.0 mV/decade at 25 °C, 7.8 mV/decade at 45 °C. We discuss how the unique characteristics of the PC-TFET open new perspectives, beyond FETs and other steep-slope transistors, for low power electronics, analog circuits and neuromorphic computing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) technology has been the core of micro/nanoelectronics industry for decades. In the Dennardian scaling era of MOS transistors, extraordinary improvements in terms of switching speed, device density, functionality and cost have been achieved by the additive application of several technology boosters such as substrate engineering, strain, multi-gate, high-k/metal gate stacks and high-mobility channel materials. However, the concept of a metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) remained unchanged. Recently, aggressive scaling of the gate length dimensions down to few tens of nanometers is facing major challenges in terms of process variability, high leakage power, unscalable voltage supply and degraded current switching ratios1.

The quest for a new beyond CMOS switch, addressing essentially leakage power and voltage scaling, encompasses new device concepts and materials, capable to complement MOSFETs and to be integrated on advanced CMOS platforms2, 3. A fundamental target is the reduction of the subthreshold swing SS (=dV g/dlogI d), which in a conventional MOSFET is limited to 60 mV/decade at room temperature (T = 300 K) due to the thermionic carrier injection mechanism4. A steep-slope switch, with SS < 60 mV/decade, would allow to scale down the supply voltage and to enable future low-power computing5. Different steep-slope device principles have been proposed for this purpose, exploiting negative capacitance6, movable electro-mechanical gates7, impact ionization8 and tunnel field-effect transistors (TFETs) based on quantum mechanical band-to-band tunnelling9 (BTBT). TFET is currently considered the most promising steep-slope solid-state switch among alternative technologies, with experimentally demonstrated SS values of the order of 30 mV/decade at room temperature10 mainly limited into a range of low currents. However, the tunnelling conduction mechanism limits the device performance in terms of ‘on’ current, I ON, and the frequency of operation.

Recently, phase change materials such as correlated functional oxides have been proposed as a promising solution for beyond CMOS electronics. External excitations applied to phase change materials can induce a phase transition accompanied by a drastic change in their conduction properties11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. One of the most studied phase change materials is vanadium dioxide (VO2), which exhibits a metal-insulator transition (MIT) corresponding to a structural phase transition at a critical temperature T MIT (340 K in bulk VO2 20,21,22). When VO2 temperature is increased above T MIT, the material transitions from a monoclinic phase to a tetragonal rutile structure, concomitant with the closing of an energy gap E g ≈ 0.6 eV in the 3d conduction band and a steep decrease in resistivity, up to 5 orders of magnitude in bulk VO2. When the VO2 temperature is decreased, the transition back to the monoclinic phase is observed for values below T MIT, giving rise to a hysteresis with width depending on the quality of the material. VO2 holds great potential for beyond CMOS electronics because the MIT can be induced by electrical excitations, enabling applications based on volatile resistive switching. The VO2-based MIT switch in 2-terminal configuration shows interesting properties such as abrupt increase in current with applied voltage23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, fast switching time32,33,34, high reliability35, 36, negative differential resistance37,38,39,40, memristive switching41, 42 and low temperature dependence of transition dynamics43, 44. However, the main drawback of the 2-terminal MIT switch is the relatively high leakage current I OFF due to the small bandgap of VO2 in the insulating state. While this problem can be mitigated by VO2 doping45, the most effective solution would be the development of 3-terminal switches in which a VO2 channel undertakes a gate-driven phase change. The development of such a device was attempted first with standard MOSFET structures using VO2 as the semiconducting material46, but the observed conductance modulation by gate voltage was limited to a small percentage47,48,49,50. This encouraged the investigation of the use of electrolyte gating to obtain very high electric fields at the interface between VO2 and an ionic liquid51, 52, inducing a higher channel conductance modulation due to the creation of oxygen vacancies53,54,55 or protonation56 but with a much slower switching time57, 58.

In order to overcome these issues, the phase-change tunnel FET (PC-TFET) has been proposed59 as a hybrid design integration of a tunnel FET and a 2-terminal MIT switch, combining the strengths of the two devices and resulting in the first solid-state VO2-based 3-terminal switch with simultaneous very low I OFF current, high I ON/I OFF ratio and ultra-steep subthreshold swing (Fig. 1a), performance that cannot be individually achieved by a TFET or a MIT switch. The transfer characteristics of the PC-TFET are qualitatively compared to the ones of the TFET used as a component part in Fig. 1b. The main working principle of the PC-TFET is to feedback (by an appropriate gate or source connection) the ultra-abrupt switching in the MIT material into a TFET characteristic, used to block the current in the OFF state. The phase change in the MIT switch corresponds to the actuation voltage V act (tunable by the design of the MIT component) allowing to switch from a high resistance state to a low resistance state, in which the current follows the transfer characteristics of the TFET. For ideal performance, the V act of a 2-terminal MIT switch should be aligned with the TFET threshold voltage V th (defined by the constant current method). Figure 1a and b also depict the resulting hysteretic behaviour of the PC-TFET, inherited from its MIT component. In this work, we discuss in detail the PC-TFET principle, its integration and the method of extraction of the body factor. Moreover, we further characterize the PC-TFET to discuss its temperature dependence and possible applications for analog circuits and neuromorphic computing.

Comparison of three steep-slope switches: TFET, MIT and proposed PC-TFET. (a) Transfer characteristics for the PC-TFET and other steep-slope switches (TFET, MIT switch) achieving lower subthreshold swing than the MOSFET. (b) PC-TFET characteristics for different values of the MIT switch threshold voltage V act, compared to the transfer characteristics of the TFET component with threshold voltage V th. The hysteresis areas for three different values of V act are highlighted by the shaded regions.

Results

Hybrid PC-TFET: principle

The principle of the PC-TFET steep slope hybrid device is to simultaneously use two physical mechanisms to lower the subthreshold swing factors m and n, respectively the body factor (mirroring the differential amplification of surface potential) and the carrier injection mechanism in the conduction channel (by band-to-band-tunnelling in a gated p-i-n junction):

while the use of band-to-band tunnelling is intrinsically offering a straightforward solution to a potentially lower than 60 mV/decade n-factor, for lowering m, in contrast with any other previous reports, we do not use any negative capacitance principle but a simple circuit technique exploiting the abrupt switching in a 2-terminal MIT device connected in a voltage divider placed in the gate or in the source of a TFET. It is worth noting that reducing the body factor, m, of a TFET below 1, corresponds to a less explored approach (previously proposed by Ionescu60) to boost the abruptness of subthreshold characteristics of a TFET.

In the following, we study two PC-TFET designs, in which the MIT switch is connected to the gate (Fig. 2a,c,e, “gate configuration”) or to the source (Fig. 2b,d,f, “source configuration”) terminal of the TFET. In both cases the state of the MIT switch is controlled by the gate voltage V GS and the phase change induces an internal differential amplification of the voltage drop V GS_INT between the gate and source terminals of the TFET (dV GS_INT/V GS >> 1) resulting in a steep increase in current I DS.

Phase change TFET integration in gate and source configuration. (a,b) 3D schematic diagrams of the PC-TFET integrating vertical VO2 switches. (c,d) 3D schematic diagrams of the PC-TFET integrating planar VO2 switches. (e,f) Equivalent circuits showing the internal TFET gate voltage V GS_INT amplified by the MIT switch phase change, induced by the external gate voltage V GS.

Figure 2a shows the hybrid design integration of a 3-terminal TFET and a 2-terminal VO2 switch to obtain the PC-TFET gate configuration. A VO2 thin film is deposited and patterned on top of the gate terminal of the TFET, and a second metal layer is used to contact it and define the gate electrode of the PC-TFET. The same design can be adapted to the source configuration, shown in Fig. 2b, where the VO2 switch is built on top of the source terminal of the TFET. An alternative design exploiting planar VO2 switches is reported in Fig. 2c for the gate configuration and Fig. 2d for the source configuration.

Figure 2e presents the equivalent circuit and voltage distribution for the PC-TFET in gate configuration. A load resistance R L is used to allow a current flow high enough to reach the power threshold of the VO2 switch43. The value of R L is selected in order to have R VO2_OFF >> R L >> R VO2_ON, where R VO2_OFF is the resistance of the MIT switch in the insulating state and R VO2_ON is the resistance in the metallic state. As V GS is ramped up in this configuration, the VO2 material is initially in the highly resistive state, hence most of the voltage drops on the MIT switch (V VO2 ≈ V GS) and V GS_INT stays low. Once the voltage is high enough to induce the metallic state in VO2, V VO2 drops to a very low value and V GS_INT experiences a steep transition to a value approaching V GS.

Figure 2f presents the equivalent circuit and voltage distribution for the PC-TFET in source configuration. In this case the MIT switch is connected to the internal source terminal of the TFET and both the internal voltage drops V GS_INT and V DS_INT are changing while sweeping V GS depending on V VO2, such that V GS − V GS_INT = V DS − V DS_INT = V VO2. For low values of V GS, the VO2 material is in its insulating state but the TFET channel resistance is much higher, effectively blocking the leakage through the MIT switch and keeping a low I OFF current. Hence V GS_INT follows V GS. Increasing V GS, the tunnelling current increases steadily until the TFET resistance becomes comparable with R VO2_OFF. At this point the rise in V GS_INT decreases and the MIT switch approaches its power threshold. Once VO2 switches to its metallic state, V GS_INT jumps abruptly to values near V GS. It is clear that the source configuration is very suitable for the lowest power consumption and aggressive scaling as it does not require any additional load resistor (which is the TFET itself) and there is no power dissipation in such a load. However, as it will be shown later, the gate configuration is particularly interesting for its steeper characteristics.

The source configuration is similar to a previously reported solution based on III–V FinFET transistors and VO2 switches61. However, that work exploited classical FinFETs with thermionic subthreshold swing and with very high leakage current to induce the phase change in VO2, and as a consequence the I ON/I OFF ratio was limited to 4 × 102 and the region of abrupt switching was observed over less than a decade of current, whereas the PC-TFET achieves simultaneously low I OFF and high I ON/I OFF ratio.

PC-TFET in gate configuration

The experimental demonstration of the PC-TFET has been achieved by fabricating and characterizing TFETs and VO2 switches connected as explained in the previous section (Fig. 2e,f). During the experimental tests, the gate voltage is doubly swept and the voltage of the internal node is recorded with a high impedance voltmeter in the whole range of device operation. This allows us to carefully derive the internal amplification and the effect of the MIT transition point on the TFET characteristics by extracting its intrinsic gate and drain voltages.

The TFETs used in this work are based on a strained silicon gate-all-around (GAA) nanowire (NW) technology62, 63 with a NW cross section of 40 × 5 nm2 and a gate length of 350 nm. In order to enable a low power design of the PC-TFET, it is necessary to minimize the power threshold of the MIT switch. Based on an electrothermal model considering Joule heating as the triggering mechanism for the abrupt MIT transition26, 64, a convenient device geometry is achieved by reducing the VO2 volume between the two electrodes of the MIT switch65. In this work such a low power actuation of a MIT switch is achieved by fabricating nanogap planar switches on a Si/SiO2 substrate, limiting the VO2 volume between the electrodes to values as low as 200 × 100 × 100 nm3 (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for details on the process flow and Supplementary Fig. 2 for images of a final device).

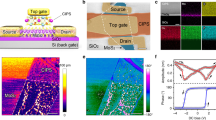

Figure 3a shows the I DS-V GS characteristics of a TFET for different values of V DS, ranging from −0.25 V to −1 V. The TFET biased at V DS = −0.75 V exhibits very low I OFF = 69.1 pA, very good I ON/I OFF = 1.0 × 107 ratio, low gate leakage I G < 8 nA up to V GS = −2 V (see Supplementary Fig. 3), and a good average subthreshold slope over 4 decades of current: SS TFET = ∂V GS/∂log10(I DS) = 112 mV/decade. Figure 3b shows the I–V characteristics of a VO2 switch at different temperatures, ranging from 25 °C to 55 °C. A 1 kΩ resistor is connected in series to the MIT switch in order to limit the current in the metallic state and prevent excessive overheating of the device. The switch design has been optimized for its use in the PC-TFET, presenting a low actuation voltage V act = −0.93 V at room temperature, steep slope of the transition (SS VO2 = 18.7 mV/decade) and capability to drive high I ON current. The transition presents limited hysteresis width (<0.2 V at room temperature) when the voltage is removed and the switch reverts to the OFF state. Increasing temperature, the actuation voltage decreases while the I ON and the slope remain stable (SS VO2 = 17.7 mV/decade at 35 °C, 23 mV/decade at 45 °C) until reaching values near T MIT, where the sharp transition is lost. This behaviour can be explained by an electrothermal actuation model based on Joule heating66.

Experimental demonstration of Phase Change TFET in gate configuration. (a) I DS-V GS transfer characteristic of the TFET for different applied V DS. (b) I-V characteristic of the VO2 switch measured at different temperatures with a series resistance of 1 kΩ. (c) I DS-V GS obtained combining (a) and (b) in gate configuration with a load resistance of R L = 1 kΩ between the gate terminal and ground and an applied V DS = −0.75 V. (d) Internal gate voltage V GS_INT biasing the TFET in function of the external applied V GS.

Figure 3c shows the I DS-V GS characteristics of the PC-TFET in gate configuration at different temperatures, biased at V DS = −0.75 V and using a load resistance R L = 1 kΩ. Different values of R L allow to shift the V GS_act level necessary to induce the phase transition (as described by additional measurements reported in Supplementary Fig. 4). Once VO2 undergoes the phase transition to the low resistivity state, we observe a sharp rise in I DS current up to values approaching the ones of the TFET at the same biasing conditions. The PC-TFET at room temperature has lower I OFF = 29.5 pA (12.3 pA/µm normalized by the TFET width) than the TFET, comparable I ON/I OFF ratio (5.5 × 106) and a subthreshold slope vastly superior to the ones of state-of-the-art TFET devices reported to date: SS PC_TFET = 4.0 mV/decade at 25 °C, 7.8 mV/decade at 45 °C. This is due to the internal amplification of V GS_INT, reported in Fig. 3d, in which we observe a very steep transition from low voltage levels to values near the TFET threshold voltage (e.g. from −0.14 V to −0.49 V at room temperature within a V GS = 10 mV step). The output characteristics of a PC-TFET in gate configuration are reported in Supplementary Fig. 5. Due to the relatively significant power consumption in the resistive divider at the gate terminal, practically dictated by the VO2 actuation (see Fig. 3b), the PC-TFET in gate configuration is not providing substantial advantages for low power electronics. However, the very abrupt transition in the PC-TFET in gate configuration can be exploited for analog circuit applications such as a voltage-controlled buffered oscillator (see Supplementary Fig. 6).

PC-TFET in source configuration

Figure 4a shows the I DS-V GS characteristics of the TFET component used to implement the PC-TFET in source configuration for different values of V DS, ranging from −0.25 V to −1.5 V. The TFET measured at T = 55 °C and biased at V DS = −0.75 V presents an average subthreshold swing SS TFET ≈ 180 mV/dec and a current ratio of 6.3 × 105 in a 2 V gate voltage window. Figure 4b shows the I-V characteristics of the VO2 switch used in this case, with a series resistance of 3 kΩ. The actuation voltage decreases with temperature from −2.61 V at 25 °C to −1.19 V at 55 °C, while the steep slope is preserved up to values approaching T MIT (SS VO2 = 11.9 mV/decade at T = 25 °C, 22.3 mV/decade at T = 55 °C).

Experimental demonstration of Phase Change TFET in source configuration. (a) I DS-V GS transfer characteristic of the TFET component for different applied V DS measured at T = 55 °C. (b) I-V characteristic of the VO2 switch measured at different temperatures with a series resistance of 3 kΩ. (c) I DS-V GS of PC-TFET obtained introducing the VO2 switch in the TFET source terminal; measurements performed at T = 55 °C with an applied external V DS = −2 V. (d) Intrinsic TFET gate voltage V GS_INT and drain voltage V DS_INT versus applied V GS.

Figure 4c depicts the I DS-V GS characteristics of the PC-TFET in source configuration. The V DS has been increased to −2 V and the measurement is reported at 55 °C in order to reach the current levels necessary to induce the transition at V GS < 4 V. The PC-TFET in source configuration combines the strengths of the two component devices, presenting a high I ON/I OFF ratio, a low I OFF current and a low I G gate leakage comparable to the TFET, while the subthreshold slope is similar to the one of the VO2 switch (SS PC_TFET = 20.6 mV/dec). The subthermionic (<60 mV/dec) value for the slope at the phase change transition is due to a similar internal gate voltage amplification mechanism exploited for the gate configuration, with the difference that both the intrinsic gate and drain voltages are simultaneously switching abruptly: V GS_INT = V GS − R VO2·I D and V DS_INT = V DS − R VO2·I D (see Fig. 4d). However, as shown in Fig. 4d, in this case the amplification occurs for values of V GS_INT above the TFET threshold (from −2.54 V to −3.31 V within a V GS = 10 mV step), resulting in a less abrupt increase in I DS. Moreover, our experiments show that the V DS_INT change while sweeping V GS is quantitatively less important than the effect of dV GS_INT/dV G amplification (see Supplementary Fig. 7).

The output characteristics of a hybrid PC-TFET in source configuration are reported in Fig. 5a, pointing out a very particular behaviour that could be further exploited in energy efficient logic or neuromorphic circuits. The VO2 phase change induces a very abrupt switching in the PC-TFET output characteristics, corresponding, in absolute values, to a higher V GS_INT and a higher V DS_INT, as pointed out by Fig. 5b. The output characteristics of PC-TFET inherit from the MIT transition points a hysteretic behaviour, which has a direct consequence on the effective drive current (because of the different trajectory on the output characteristics in logical switching) if such device is used for building CMOS inverters. Moreover, the low leakage current in the PC-TFET, negligible with respect to the drain current over the whole domain of operation (see Supplementary Fig. 8), makes it promising for energy efficient implementations of neuromorphic circuits based on relaxation oscillators67, 68.

Output characteristics and drain voltage switching of Phase Change TFET in source configuration. (a) Output characteristics of PC-TFET in source configuration for different applied V GS (ranging from −2.75 V to −4 V) measured at T = 55 °C. (b) Intrinsic TFET gate voltage V GS_INT and drain voltage V DS_INT versus applied V DS.

Body factor reduction in PC-TFET

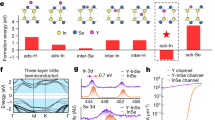

The deep subthermionic switching in the PC-TFET can be explained by its sub-unity body factor due to the internal gate voltage amplification. The relation between the subthreshold slope and the body factor has been captured in equation (1), with the transistor body factor m = dV GS/dΨ S expressed as the inverse of the differential amplification of the surface potential with respect to the extrinsic gate voltage. In a conventional MOSFETs the body factor is dependent on a capacitance ratio between the gate oxide capacitance, C ox, and the depletion capacitance, C d, m = 1 + C d/C ox, resulting in a lower bound, m ≥ 1. Here, we show that this limit is overcome in the PC-TFET because the body factor m can be expressed in function of V GS_INT and becomes:

hence, when maximizing the internal gain of the PC-TFET, G = dV GS_INT/dV GS >> 1, and given that in fully depleted body devices (1 + C d/C ox)~1, it follows that m << 1, showing that the body factor is a booster of the TFET subthreshold swing. We extract the body factor from our experimental results, starting from calculating the surface potential as a function of V GS as shown in Fig. 6a, for the gate configuration, and Fig. 6b, for the source configuration. On the same figures we include the measured internal gain, G, whose experimental values are used to extract m, using equation (2). The values of Ψ S(V GS) are obtained by means of technology computer-aided design (TCAD) simulations of NW-TFETs identical to the fabricated structures, biased with the experimental values of V GS_INT and V DS for the gate configuration (Fig. 3d), V GS_INT and V DS_INT for the source configuration (Fig. 4d). We observe a steep change in Ψ S (resulting in a very low m) in correspondence of the V GS values for which a high internal gain amplification is recorded, highlighting the key role of the internal gain in the steep switching characteristics of the PC-TFET.

Surface potential and body factor in Phase Change TFET. (a,b) Dependence on V GS of the surface potential, Ψ S, and internal gain, G = dV GS_INT/dV GS, for gate and source configurations. The reference level for the surface potential is taken at the source terminal. (c,d) Body factor as a function of I DS for gate and source configurations; the dashed lines represent the m ≥ 1 limit overcome thanks to the internal V GS_INT amplification.

Figure 6c,d show m in function of the measured I DS, respectively for the gate and source configurations. In both cases the experimentally extracted body factor shows a less than 0.1 value in the transition region. The PC-TFET in gate configuration presents a value of m of ~0.05 (<<1) for more than two decades of current, from 0.43 nA to 142.3 nA in the OFF to ON transition and from 27.5 nA to 0.15 nA in the OFF to ON transition. The PC-TFET in source configuration shows similar values of m (0.025 in the OFF to ON transition, 0.5 in the ON to OFF). It is worth noting that the low-m region is extended for more decades of current in the gate configuration due to the better alignment of the internal gain peaks and the TFET threshold region.

Discussion

We reported the PC-TFET as a novel hybrid steep-slope electronic switch, combining two steep switching mechanisms in a single device, and its detailed characterization in a broad range of temperatures up to values approaching the transition temperature of VO2. The unique combination of BTBT in TFET and MIT in VO2 leads to excellent figures of merit for digital electronics such as an I on/I off ratio better than 5.5 × 106 and a subthreshold swing lower than 10 mV/dec over 3 decades of currents. We observe low dependence on temperature of the swing of the PC-TFET in gate configuration, ranging from 4.0 mV/dec at room temperature to 7.8 mV/dec at 45 °C. Moreover, we have demonstrated that the underlying mechanism for the abrupt switching behaviour is the internal gate voltage amplification, leading to a sub-unity equivalent body factor. Such lower-than-1 body factor to achieve subthermionic switching is a much more general design criterion than the previous principle of negative capacitance, serving as a performance booster for both TFETs and MOSFETs. The PC-TFET represents an important step forward for beyond CMOS electronics, exploiting for the first time the full potential of the VO2 MIT in in an electrically gated 3-terminal architecture and opening new perspectives for low power electronics and neuromorphic computing.

Methods

Fabrication of experimental devices

VO2 nanogap switches were fabricated on a silicon substrate with a 200 nm thick SiO2 layer on top. The VO2 layer was deposited by reactive magnetron sputtering at 600 °C of a pure vanadium target, with detailed experimental conditions reported elsewhere69. Electrical contacts were defined by electron beam lithography on PMMA/MMA and lift-off of a 100 nm thick platinum film deposited by sputtering. The VO2 areas around the switch are then removed by electron beam lithography on ZEP and ion beam etching. Strained silicon GAA TFETs have been fabricated on a silicon on insulator substrate using a process based on doping segregation from NiSi2 70.

TCAD simulations for surface potential extraction

TCAD simulations were performed using Sentaurus TCAD Suite 2014.09. We simulated a strained silicon double gate TFET with channel thickness T CH = 5 nm, oxide thickness T OX = 3 nm with HfO2 (ε r = 22) gate metal workfunction of ϕ m = 4.1 eV corresponding to TiN. The source doping is N S = 1 × 1020 cm−3 and the drain doping is N D = 1 × 1019 cm−3 with abrupt junctions. Since the semiconductor layer is extremely thin, we have enlarged the bandgap by 70 meV, corresponding to the quantized state of the [100] ellipsoids. However, this increase is cancelled out by the strain on the nanowires, which results in an overall bandgap reduction of ΔE g = −25 meV. All the simulated surface potential values reported in this work are taken from 0.1 Å below the semiconductor-oxide interface. The surface potential plots in function of V GS (Fig. 5a,b) are taken at the tunneling junction, while the full potential profile across the channel is reported in Supplementary Fig. 9.

References

Iwai, H. Technology roadmap for 22nm and beyond. In 2009 2nd Int. Work. Electron Devices Semicond. Technol. 1–4, doi:10.1109/EDST.2009.5166100 (IEEE, 2009).

Bernstein, K., Cavin, R. K., Porod, W., Seabaugh, A. & Welser, J. Device and Architecture Outlook for Beyond CMOS Switches. Proc. IEEE 98, 2169–2184 (2010).

Seabaugh, A. C. & Zhang, Q. Low-voltage tunnel transistors for beyond CMOS logic. Proc. IEEE 98, 2095–2110 (2010).

Lundstrom, M. S. The MOSFET Revisited: Device Physics and Modeling at the Nanoscale. In 2006 IEEE international SOI Conferencee Proceedings 1–3, doi:10.1109/SOI.2006.284404 (IEEE, 2006).

Ionescu, A. M. & Riel, H. Tunnel field-effect transistors as energy-efficient electronic switches. Nature 479, 329–337 (2011).

Salahuddin, S. & Datta, S. Use of negative capacitance to provide voltage amplification for low power nanoscale devices. Nano Lett. 8, 405–410 (2008).

Abele, N. et al. Suspended-gate MOSFET: bringing new MEMS functionality into solid-state MOS transistor. In IEEE Int. Electron Devices Meet. 2005. IEDM Tech. Dig. 479–481, doi:10.1109/IEDM.2005.1609384 (IEEE, 2005).

Gopalakrishnan, K., Griffin, P. B. & Plummer, J. D. I-MOS: a novel semiconductor device with a subthreshold slope lower than kT/q. In Dig. Int. Electron Devices Meet. 289–292, doi:10.1109/IEDM.2002.1175835 (IEEE, 2002).

Boucart, K. & Ionescu, A. M. Double-gate tunnel FET with high-k gate dielectric. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 54, 1725–1733 (2007).

Sarkar, D. et al. A subthermionic tunnel field-effect transistor with an atomically thin channel. Nature 526, 91–95 (2015).

Newns, D. M. et al. Mott transition field effect transistor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 73, 780 (1998).

Inoue, I. H. Electrostatic carrier doping to perovskite transition-metal oxides. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 20, S112–S120 (2005).

Inoue, I. H. & Rozenberg, M. J. Taming the mott transition for a novel mott transistor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 18, 2289–2292 (2008).

Ha, S. D. & Ramanathan, S. Adaptive oxide electronics: A review. J. Appl. Phys. 110, 071101 (2011).

Yang, Z., Ko, C. & Ramanathan, S. Oxide Electronics Utilizing Ultrafast Metal-Insulator Transitions. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 41, 337–367 (2011).

Basov, D. N., Averitt, R. D., Van Der Marel, D., Dressel, M. & Haule, K. Electrodynamics of correlated electron materials. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 471–541 (2011).

Zhou, Y. & Ramanathan, S. Correlated Electron Materials and Field Effect Transistors for Logic: A Review. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci 38, 286–317 (2013).

Mannhart, J. & Haensch, W. Device physics: Put the pedal to the metal. Nature 487, 436–437 (2012).

Shi, J., Zhou, Y. & Ramanathan, S. Colossal resistance switching and band gap modulation in a perovskite nickelate by electron doping. Nat. Commun. 5, 4860 (2014).

Morin, F. J. Oxides which show a metal-to-insulator transition at the neel temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 3, 34–36 (1959).

Mott, N. F. Metal-insulator transition. Rev. Mod. Phys. 40, 677–683 (1968).

Goodenough, J. B. The two components of the crystallographic transition in VO2. J. Solid State Chem. 3, 490–500 (1971).

Lee, S. B., Kim, K., Oh, J. S., Kahng, B. & Lee, J. S. Origin of variation in switching voltages in threshold-switching phenomena of VO2 thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 63501 (2013).

Simon Mun, B. et al. Role of joule heating effect and bulk-surface phases in voltage-driven metal-insulator transition in VO2 crystal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103 (2013).

Yoon, J., Lee, G., Park, C., Mun, B. S. & Ju, H. Investigation of length-dependent characteristics of the voltage-induced metal insulator transition in VO2 film devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 83503 (2014).

Jordan, T. S. et al. Model and Characterization of VO2 Thin-Film Switching Devices. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 61, 813–819 (2014).

Rathi, S. et al. Postfabrication annealing effects on insulator-metal transitions in VO2 thin-film devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 19718–19725 (2014).

Rathi, S. et al. Unravelling the switching mechanisms in electric field induced insulator–metal transitions in VO2 nanobeams. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 47, 295101 (2014).

Joushaghani, A. et al. Voltage-controlled switching and thermal effects in VO2 nano-gap junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 221904 (2014).

Singh, S. et al. Proliferation of metallic domains caused by inhomogeneous heating near the electrically driven transition in VO2 nanobeams. Phys. Rev. B 92, 155121 (2015).

Li, D. et al. Joule Heating-Induced Metal–Insulator Transition in Epitaxial VO2/TiO2 Devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces acsami.6b03501, doi:10.1021/acsami.6b03501 (2016).

Chae, B. G., Kim, H. T., Youn, D. H. & Kang, K. Y. Abrupt metal-insulator transition observed in VO2 thin films induced by a switching voltage pulse. Phys. B Condens. Matter 369, 76–80 (2005).

Leroy, J. et al. High-speed metal-insulator transition in vanadium dioxide films induced by an electrical pulsed voltage over nano-gap electrodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 213507 (2012).

Zhou, Y. et al. Voltage-Triggered Ultrafast Phase Transition in Vanadium Dioxide Switches. IEEE Electron Device Lett 34, 220–222 (2013).

Vitale, W. A. et al. Steep slope VO2 switches for wide-band (DC-40 GHz) reconfigurable electronics. In 72nd Device Research Conference 29–30, doi:10.1109/DRC.2014.6872284 (IEEE, 2014).

Radu, I. P. et al. Switching mechanism in two-terminal vanadium dioxide devices. Nanotechnology 26, 165202 (2015).

Sakai, J. High-efficiency voltage oscillation in VO2 planer-type junctions with infinite negative differential resistance. J. Appl. Phys. 103, 103708 (2008).

Lee, Y. W. et al. Metal-insulator transition-induced electrical oscillation in vanadium dioxide thin film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92 (2008).

Shukla, N. et al. Synchronized charge oscillations in correlated electron systems. Sci. Rep 4, 4964 (2014).

Beaumont, A., Leroy, J., Orlianges, J.-C. & Crunteanu, A. Current-induced electrical self-oscillations across out-of-plane threshold switches based on VO2 layers integrated in crossbars geometry. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 154502 (2014).

Bae, S. H. et al. The memristive properties of a single VO2 nanowire with switching controlled by self-heating. Adv. Mater. 25, 5098–5103 (2013).

Seo, G., Kim, B. J., Kim, H. T. & Lee, Y. W. Thermally- or optically-biased memristive switching in two-terminal VO2 devices. Curr. Appl. Phys. 14, 1251–1256 (2014).

Vitale, W. A. et al. Steep-Slope Metal–Insulator-Transition VO2 Switches With Temperature-Stable High ION. IEEE Electron Device Lett 36, 972–974 (2015).

Vitale, W. A. et al. Field-enhanced design of steep-slope VO2 switches for low actuation voltage. In 2016 46th European Solid-State Device Research Conference (ESSDERC), 352–355, doi:10.1109/ESSDERC.2016.7599659 (IEEE, 2016).

Krammer, A., Gremaud, A., Bouvard, O., Sanjines, R. & Schüler, A. In situ photoelectron spectroscopic characterization of reactively sputtered, doped vanadium oxide thin films. Surf. Interface Anal. 1–5, doi:10.1002/sia.5989 (2016).

Kim, H.-T. et al. Mechanism and observation of Mott transition in VO2-based two- and three-terminal devices. New J. Phys. 6, 52–52 (2004).

Ruzmetov, D., Gopalakrishnan, G., Ko, C., Narayanamurti, V. & Ramanathan, S. Three-terminal field effect devices utilizing thin film vanadium oxide as the channel layer. J. Appl. Phys. 107, 114516 (2010).

Sengupta, S. et al. Field-effect modulation of conductance in VO2 nanobeam transistors with HfO2 as the gate dielectric. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 62114 (2011).

Martens, K. et al. Field Effect and Strongly Localized Carriers in the Metal-Insulator Transition Material VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 196401 (2015).

Wei, T., Kanki, T., Fujiwara, K., Chikanari, M. & Tanaka, H. Electric field-induced transport modulation in VO2 FETs with high-k oxide/organic parylene-C hybrid gate dielectric. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 53503 (2016).

Nakano, M. et al. Collective bulk carrier delocalization driven by electrostatic surface charge accumulation. Nature 487, 459–62 (2012).

Liu, K. et al. Dense electron system from gate-controlled surface metal-insulator transition. Nano Lett. 12, 6272–7 (2012).

Jeong, J. et al. Suppression of Metal-Insulator Transition in VO2 by Electric Field-Induced Oxygen Vacancy Formation. Science 339, 1402–1405 (2013).

Karel, J. et al. Distinct Electronic Structure of the Electrolyte Gate Induced Conducting Phase in Vanadium Dioxide Revealed by High Energy Photoelectron Spectroscopy. ACS Nano 8, 5748–5789 (2014).

Jeong, J. et al. Giant reversible, facet-dependent, structural changes in a correlated-electron insulator induced by ionic liquid gating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 112, 1013–1018 (2015).

Shibuya, K. & Sawa, A. Modulation of Metal-Insulator Transition in VO2 by Electrolyte Gating-Induced Protonation. Adv. Electron. Mater 2, 1500131 (2016).

Zhou, Y. & Ramanathan, S. Relaxation dynamics of ionic liquid-VO2 interfaces and influence in electric double-layer transistors. J. Appl. Phys. 111, 84508 (2012).

Peng, X. et al. Efficient and Hysteresis-Free Field Effect Modulation of Ambipolarly Doped Vanadium Dioxide Nanowires. Phys. Rev. Appl 5, 54008 (2016).

Casu, E. A. et al. Hybrid Phase-Change – Tunnel FET (PC-TFET) Switch with Subthreshold Swing <10 mV/decade and sub-0.1 body factor: digital and analog benchmarking. In 2016 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (2016).

Ionescu, A. M. Ferroelectric tunnel FET switch and memory. US patent (2010).

Shukla, N. et al. A steep-slope transistor based on abrupt electronic phase transition. Nat. Commun. 6, 7812 (2015).

Zhao, Q. T. et al. Strained Si and SiGe nanowire tunnel FETs for logic and analog applications. IEEE J. Electron Devices Soc 3, 103–114 (2015).

Knoll, L. et al. Strained Si and SiGe tunnel-FETs and complementary tunnel-FET inverters with minimum gate lengths of 50 nm. Solid. State. Electron. 97, 76–81 (2014).

Zimmers, A. et al. Role of Thermal Heating on the Voltage Induced Insulator-Metal Transition in VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 56601 (2013).

Joushaghani, A. et al. Characteristics of the Current-Controlled Phase Transition of VO2 Microwires for Hybrid Optoelectronic Devices. Photonics 2, 916–932 (2015).

Vitale, W. A., Moldovan, C. F., Paone, A., Schüler, A. & Ionescu, A. M. Investigation of the Metal-Insulator Transition in VO2 for Electronic Switches with Sub-1 mV/Decade Steep Subthreshold Slope. In Silicon Nanoelectronics Workshop, doi:10.1109/SNW.2016.7578041 (2016).

Shukla, N. et al. Pairwise coupled hybrid vanadium dioxide-MOSFET (HVFET) oscillators for non-boolean associative computing. In 2014 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting 28.7.1-28.7.4, doi:10.1109/IEDM.2014.7047129 (IEEE, 2014).

Jerry, M. et al. Phase transition oxide neuron for spiking neural networks. In 74th Annual Device Research Conference 1-2, doi:10.1109/DRC.2016.7548503 (IEEE, 2016).

Vitale, W. A., Moldovan, C. F., Paone, A., Schüler, A. & Ionescu, A. M. Fabrication of CMOS-compatible abrupt electronic switches based on vanadium dioxide. Microelectron. Eng. 145, 117–119 (2015).

Luong, G. V., Trellenkamp, S., Zhao, Q. T., Mantl, S. & Bourdelle, K. K. Strained Si nanowire GAA n-TFETs for low supply voltages. EUROSOI-ULIS 2015 - 2015 Jt. Int. EUROSOI Work. Int. Conf. Ultim. Integr. Silicon 65–68, doi:10.1109/ULIS.2015.7063774 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the ERC Advanced Grant ‘Millitech’ of the European Commission, the E2SWITCH FP7 Project (Grant Agreement No. 257267), the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant No. 144268) and the Swiss Federal Office of Energy (Grant No. 8100072).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.A.V., E.A.C. and A.B. performed the experiments. W.A.V., E.A.C. and C.A. analyzed the data. T.R. designed and simulated the circuit applications. A.K. and A.S. deposited the VO2 films. E.A.C. fabricated the VO2 switches. G.V.L., Q.-T.Z. and S.M. designed and fabricated the TFETs. W.A.V. and A.M.I. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. A.M.I. directed the overall research project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Vitale, W.A., Casu, E.A., Biswas, A. et al. A Steep-Slope Transistor Combining Phase-Change and Band-to-Band-Tunneling to Achieve a sub-Unity Body Factor. Sci Rep 7, 355 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00359-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00359-6

This article is cited by

-

Elevated Transition Temperature of VO2 Thin Films via Cr Doping: A Combined Electrical Transport and Electronic Structure Study

Journal of Electronic Materials (2023)

-

3D Smith charts scattering parameters frequency-dependent orientation analysis and complex-scalar multi-parameter characterization applied to Peano reconfigurable vanadium dioxide inductors

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Steep switching devices for low power applications: negative differential capacitance/resistance field effect transistors

Nano Convergence (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.