Abstract

Monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) including WS2, MoS2, WSe2 and WS2, are two-dimensional semiconductors with direct bandgap, providing an excellent field for exploration of many-body effects in 2-dimensions (2D) through optical measurements. To fully explore the physics of TMDCs, the prerequisite is preparation of high-quality samples to observe their intrinsic properties. For this purpose, we have focused on high-quality samples, WS2 grown by chemical vapor deposition method with hexagonal boron nitride as substrates. We observed sharp exciton emissions, whose linewidth is typically 22~23 meV, in photoluminescence spectra at room temperature, which result clearly demonstrates the high-quality of the current samples. We found that biexcitons formed with extremely low-excitation power (240 W/cm2) at 80 K, and this should originate from the minimal amount of localization centers in the present high-quality samples. The results clearly demonstrate that the present samples can provide an excellent field, where one can observe various excitonic states, offering possibility of exploring optical physics in 2D and finding new condensates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) provide a fascinating playground for studies of optical and device physics in two dimensions. TMDCs including MoS2, WS2, MoSe2 and WSe2 are layered semiconductors that are composed of a transition metal layer sandwiched by chalcogen layers with trigonal prismatic coordination geometry1. Importantly, these TMDCs can be isolated as their monolayer form, and they are 2D direct-gap semiconductors at monolayer thickness2,3,4. Due to their 2D structure, many-body effects in TMDCs are prominent, which, for example, results in strong excitonic effects in optical transitions5. In fact, photoluminescence (PL) spectra of monolayer TMDCs exhibit strong emissions arising from excitons (electron-hole pairs) and trions (charged excitons) even at room temperature6,7,8, and these results suggest an opportunity to find further peculiar complex many-body states such as higher-order excitons, electron-hole plasma and exciton condensates in TMDCs9,10,11,12.

To further explore the fundamental properties of TMDCs, the important point is preparation of high-quality samples to ensure their intrinsic properties. High-quality samples can show sharp excitonic PL that arises from the long dephasing time and the minimal amount of structural roughness. This leads to easier observation of fine structures in a PL spectrum, giving more chance to observe new excitonic states13. In order to realize high-quality samples, we have focused on monolayer WS2 directly grown on hexagonal boron nitride (hBN)14, where an ideal atomically flat surface virtually without dangling bonds is available. The monolayer WS2 grown on hBN (WS2/hBN) is thus atomically flat with clean interfaces, showing PL peaks whose full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) are much smaller than those of mechanically exfoliated and samples grown onto other substrates14,15,16. Using WS2/hBN, we have observed the formation of biexcitons at 80 K even with extremely low excitation power of 2.8 μW or 240 W/cm2, which is 18 or 125 times smaller, respectively, than those reported previously17, 18.

Results

CVD Growth of WS2 on hBN and characterization

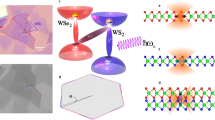

We have prepared WS2/hBN by the chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method with WO2.9 and elemental sulfur as source materials together with exfoliated hBN flakes as substrates. To check the layer number of WS2 grown on hBN, we performed PL imaging, atomic force microscopy (AFM), Raman and PL spectroscopy for the respective samples. Figure 1a,b,c and d show a typical PL image, a structure model of WS2/hBN, Raman and PL spectra, respectively. Because monolayer WS2 is a direct-gap semiconductor, crystals of monolayer WS2 can be seen as bright triangular contrasts in the PL images; the triangular shape arises from preferential appearance of zig-zag edges during the growth, being consistent with previous reports on CVD-growths of TMDCs17, 19, 20. A typical AFM image of the WS2/hBN clearly demonstrate the triangular crystal shape with a thickness of 0.7 nm, which is consistent with the monolayer WS2 structure (Figure S1)20. The monolayer structure of WS2 can further be confirmed by the Raman spectrum (Fig. 1c), where the peak separation between E′ (358.6 cm−1) and A′1 (419.8 cm−1) modes is 61.2 cm−1 in consistent with monolayer WS2 19, 21. The strong and narrow emission peak at 2.014 eV in the PL spectrum (Fig. 1d, taken with excitation energy of 2.54 eV) can be assigned to neutral excitons of monolayer WS2. All results shown above clearly demonstrate the successful growth of monolayer WS2 on hBN.

(a) A PL image of WS2/hBN. The PL image was taken with 488 nm excitation. This image is combination of transmission bright field image (monochrome) and 600–700 nm detection (red). (b) Structure model of WS2 grown on hBN. Yellow, Green, blue and orange spheres represent sulfur, tungsten, nitrogen and boron atoms, respectively. B and N atoms are drawn with van der Waals radii, and Mo and S are drawn with the ball-and-stick model. (c) A typical Raman spectrum of WS2/hBN. (d) A typical PL spectrum of WS2/hBN. The excitation energy of 2.54 eV was used to measure the Raman and PL spectrum.

Crystal quality can be confirmed by the Raman and PL spectrum. The Raman spectrum shows two strong Raman bands that are assigned to E′ and A′1 modes. The observed Raman bands are sharp (i.e., FWHM of the A′1 Raman band is 2.8 cm−1)17, 22, which clearly demonstrates the high crystallinity of the current WS2 crystal. The observed FWHM of the PL emission in Fig. 1c, 22.5 meV, is much smaller than those of the exfoliated WS2 and the CVD-grown WS2 (grown on SiO2/Si or sapphire substrates); typical values of FWHM reported range from 42 to 75 meV19, 23, 24. The small FWHM should originate from high quality of the grown WS2/hBN, indicating less surface roughness and amount of defects. The less surface roughness can be directly confirmed by the height profile of the AFM (Figure S1), where the atomically flat surface of WS2 grown on hBN is clearly seen. A transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of WS2/hBN (shown in Figure S2) shows lattice fringes of WS2, and the corresponding electron diffraction pattern clearly demonstrates the match in the crystallographic orientation between WS2 and hBN, manifesting a smooth and clean interface existing between WS2 and hBN.

Temperature dependence in photoluminescence of WS2/hBN

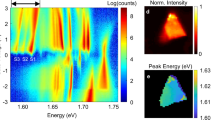

To further explore excitonic states in WS2, we measured temperature dependence of PL spectra. Figure 2a shows PL spectra of WS2/hBN measured at temperatures ranging from 81.7 to 310 K. As seen in Fig. 2a, the emission peak from excitons shifts to the lower energy side when temperature decreases. The peak shift can be well fitted by Varshni’s formula (Figure S3 and Table S1), which explains bandgap change caused by electron-phonon interaction25. As seen in Fig. 2a, additional peaks appear when temperature is lower than 225 K. We used excitation energy of 2.54 eV to measure the PL spectra, and electrons and holes generated by the excitation relax to the conduction band bottom as well as the valence band top at K (K′) points in Brillouin zone, leading to formation of neutral free excitons26. At low temperature, fee excitons generated can be trapped by localized centers or can form trions, while these states are not observable at high temperature due to the thermal dissociation into free excitons. In the case of WS2 grown on sapphire, no additional PL peaks are observed in PL spectra even at 80 K, which fact clearly shows significance of the substrate effect to observe fine structures of excitonic states (Figure S4).

(a) PL spectra of WS2/hBN measured at temperatures ranging from 81.7 to 310 K. (b) A PL spectrum of WS2/hBN measured at 80 K. Contribution from excitons, trions, P1 and P2, which are shown by black, blue green and red curves, respectively, are modeled by the pseudo-voigt function. Excitation energies of 2.54 eV and 2.38 eV were used to measure spectra in (a) and the spectrum in (b), respectively.

Figure 2b shows the PL spectrum of WS2/hBN at 80 K, where three additional emission peaks are seen at the lower energy side of the PL of neutral excitons. As clearly seen in the spectrum, the emission peaks are well-separated each other, leading to an easy identification of additional excitonic states in the present sample. The emission at 2.036 eV can be assigned to trions based on the binding energy of 39 meV, and the formation of trions in the present sample indicates that there are accidentally-doped free carriers in the sample27. The intensity of the trion emission at room temperature is almost negligible, which results from small amount of the free carriers in the sample.

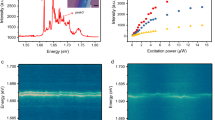

In addition to emission peaks from neutral excitons and trions, we can see two strong emission peaks at 2.015 (P1) and 1.998 (P2) eV. To address the origin of the additional peaks, we measured excitation power dependence of PL spectra. In this measurements, we used excitation energy of 2.38 eV with pulse width of 20 ps. Figure 3a shows PL spectra measured with the excitation power ranging from 0.37 to 6.6 μJ/cm2 at 80 K; the intensities of the PL spectra are normalized in such a way that intensity of neutral exciton is one. As clearly seen in the figure, P2 peak becomes prominent as excitation power increases, whereas P1 peak is almost comparable to the neutral exciton peak throughout the all spectra.

(a) PL spectra of WS2/hBN measured with excitation power ranging from 0.37 to 6.6 μJ/cm2 at 80 K. (b,c) Plots of PL intensities of trion, P1 and P2 verses that of exciton. Green, blue and red filled squares correspond to PL intensities of P1, trion and P2, respectively. Solid lines corresponds to fitted lines based on the relation of I ∞ I ex α.

Discussion

Figures 3b and c show the relation in PL intensity between the exciton emission and other emissions. As expected, the intensity of the trion emission is almost proportional to that of the neutral exciton emission; a fitting using the equation, I tri ∝ I ex α (I tri , I ex and α correspond to the intensity of trion emission, the intensity of exciton emission and constant, respectively) gives α of 1.08. The intensity of P1 is also almost proportional to that of exciton, and a fitting using the same equation yields α of 1.25. The obtained value of α, which is close to 1, means that the P1 state is also formed through a one-exciton process where an exciton, for example, captures a free carrier, namely a fine structure of trion, or is trapped by impurities.

In contrast, in Fig. 3c, the intensity of P2 clearly shows super-liner relation against the intensity of excitons, providing α value of 1.82. The observed super-liner relation strongly suggests that the P2 emission peak originates from biexcitons28, 29. The observed binding energy of the P2 peak is ca. 75 meV, which yields Haynes factor (the ratio in binding energy between excitons and biexcitons) of 0.09–0.23; the exciton binding energy reported ranges from 0.32 to 0.71 eV7, 8, 30. The calculated Haynes factor is consistent with those of quantum-well systems and other TMDCs28, 31, 32. Valley polarization measurements (Figure S6) also support that the P2 peak originates from biexcitons. As shown in Figure S6, P2 peak shows a valley polarization of 12.7%, which excludes the possibility that the P2 peak originates from bound excitons or bound biexcitons28.

Figure 4 shows time-resolved PL intensities. Fitting of the experimental curves in Fig. 4 based on a single exponential decay yielded the relaxation time of excitons (τ ex), trions (τ tri) and biexcitons (τ b) as 15, 22 and 31 ps, respectively. When thermal equilibrium between excitons and biexcitons is reached, τ ex should be twice as large as τ b. This is, however, not the present case because the measurement was performed at 80 K and the biexciton binding energy of 75 meV is much larger than the thermal energy of 80 K (6.9 meV), which situation should make the biexciton to exciton conversion extremely slow. The temperature, 80 K, is almost ten times smaller than the binding energy of biexcitons, leading to the complete blocking of the biexciton to exciton conversion process28, 33. The observed relation between τ X and τ XX is therefore consistent with the formation of biexcitons with the large binding energy (for details, see Supporting information)28. The observed binding energy of biexciton, 75 meV, is larger than those reported previously17, 18, 34, 35. Biexcitons are larger than excitons, and biexcitons are supposed to be more sensitive to the screening. The different environment and density of free carrier in WS2/hBN might contribute to the observed large binding energy.

In previous studies, the biexciton emission have been observed with excitation power of, for example, 50 μW and 30 kW/cm2 at 77 and 4 K, respectively17, 18. In contrast, in our samples, the biexciton emission can be clearly seen with much smaller excitation power of 2.8 μW or 240 W/cm2 at 81.7 K (Fig. 5). Considering the absorption coefficient reported20, the excitation power can be converted to the maximum density of excitons generated, 2.5 × 108/cm2, giving the average exciton-exciton distance as 630 nm. In this experiment, biexcitons were formed through the exciton-exciton collision, and the exciton-exciton distance should be comparable to the exciton diffusion length, L ex . The L ex can be calculated using the following formula, L ex = 2(D ex τ ex )1/2, where τ ex and D ex are the lifetime (15 ps) and the diffusion coefficient of exciton, respectively. The exciton diffusion coefficient can be estimated from the Einstein relation D ex ~ k B T/M ex Δ, where k B , M ex and Δ are the Boltzmann constant, the exciton translational mass (~0.55 m 0 )36 and homogeneous linewidth of exciton (~3.2 meV); the homogeneous linewidth was determined through spectral fitting with the Voigt function. Using the obtained D ex of ~9.3 cm2/s, L ex was estimated to be ~240 nm, which is comparable to the average exciton-exciton distance. The small homogenous linewidth of the exciton emission means that the dephasing time of excitons in the present sample is long, leading to the long L ex up to 240 nm even with the short τ ex . The long L ex might originate from significant decrease in roughness scattering in ultraflat WS2 in our WS2/hBN samples.

In addition to the flatness, the small amount of trap centers and free carriers in WS2/hBN also helps to form biexcitons. As shown in Fig. 3a, PL emission from localized excitons, which have been observed typically at 1.8~2.0 eV, is strongly suppressed under higher excitation power34. This means that the amount of the trap centers in the current samples is smaller than those in previous studies34. In addition, as already discussed, the amount of free carriers in the present sample is small, which lead to less formation of trions. Higher order excitons including biexcitons are formed through collisions of excitons, and other processes such as the formation of localized excitons and trions compete with the formation of biexcitons. The fewer amount of trap centers thus contribute to an easy observation of biexcitons in our high-quality samples. The difference may originates from the difference in substrates, and surface roughness, charged impurities and dangling bonds in ordinal substrates like SiO2/Si are the origin of the trap centers37.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have grown a high-quality WS2 on hBN substrates by the CVD method. The present WS2/hBN sample shows a sharp PL emission at room temperature, and the low temperature PL shows additional peaks originating from biexcitons. The power dependence and valley polarization measurements are consistent with the formation of biexcitons. Biexcitons are formed with extremely low-excitation power, 240 W/cm2, which originates from the minimal amount of localization centers in the present high-quality samples. These results clearly demonstrate that the present samples can provide an excellent field, where one can observe various excitonic states, offering possibility of exploring optical physics in 2D and finding new condensates.

Methods

CVD growth of WS2 on hBN

We have grown WS2 atomic layers by CVD method with elemental sulfur (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.998%) and tungsten oxide (WO2.9, Alfa Aesar, 99.99%) as precursors. We prepared thin hBN flakes, whose thickness is typically several tens of nanometers, on sapphire or quartz substrate by the mechanical exfoliation method, and the exfoliated thin hBN flakes were used as substrates for the CVD growth of WS2 atomic layers. A substrate with hBN flakes, WO2.9 and sulfur were placed in a quartz tube with diameter of 26 mm; the WO2.9 was placed in a quartz tube whose inner diameter is 8 mm to avoid rapid sulfurization of WO2.9. Under Ar flow of 200 sccm, the quartz tube was heated with three-zone furnace at 190, 400 and 1050 degree for 30 minutes; a substrate with hBN flakes and sulfur were placed at the hottest and coldest zone, respectively.

Photoluminescence (PL) and Raman measurement

We obtained PL images by a fluorescence microscope (Leica TCS SP8 gSTED) with excitation wavelength of 488 nm at room temperature. Raman and PL spectra were measured by using a confocal-microscope based Raman microscopy (Jobin Yvon LabRAM HR-800) with 488 nm excitation (CW laser, COHERENT Sapphire 488 LP). In measurements of Raman spectra, a notch filter was used to filter out the intense signal from Rayleigh scattering. An objective lens (100 x, 0.9 NA) was used to focus the laser light onto a sample and collect the backscattered light from the sample. Raman and PL signal were detected with a charge-coupled device. In temperature dependence measurements, we placed WS2/hBN in a cryostat (CryoVac KONTI-Cryostat-Micro) with continuous flowing of liquid N2 under vacuum of ~10−6 Torr. Temperature was controlled by a CryoVac TIC 304-MA.

AFM and TEM observations

AFM images were obtained with a Veeco Dimension 3100. High-resolution TEM images were taken with a JEM-2100F (JEOL) operated at 80 keV. We transferred hBN flakes with grown WS2 onto a copper TEM grid by the standard polymer-based transfer technique. TEM images were recorded with a charge-coupled device with exposure time of typically 1~3 seconds. Electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) and energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy were carried out with a post column spectrometer (gatan Enfina) and an in column spectrometer, respectively.

References

Ding, Y. et al. First principles study of structural, vibrational and electronic properties of graphene-like MX2 (M = Mo, Nb, W, Ta; X = S, Se, Te) monolayers. Physica B: Condensed Matter 406, 2254–2260 (2011).

Kuc, A., Zibouche, N. & Heine, T. Influence of quantum confinement on the electronic structure of the transition metal sulfide TS2. Phys. Rev. B 83, 245213 (2011).

Mak, K. F., Lee, C., Hone, J., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010).

Kumar, A. & Ahluwalia, P. Electronic structure of transition metal dichalcogenides monolayers 1H-MX2 (M = Mo, W; X = S, Se, Te) from ab-initio theory: new direct band gap semiconductors. Eur. Phys. J. B 85, 1–7 (2012).

Ramasubramaniam, A. Large excitonic effects in monolayers of molybdenum and tungsten dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 86, 115409 (2012).

Berkelbach, T. C., Hybertsen, M. S. & Reichman, D. R. Theory of neutral and charged excitons in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 88, 045318 (2013).

Chernikov, A. et al. Exciton binding energy and nonhydrogenic Rydberg series in monolayer WS2. Phys. Rev. lett. 113, 076802 (2014).

Zhu, B., Chen, X. & Cui, X. Exciton binding energy of monolayer WS2. Sci. rep . 5 (2015).

Wang, H., Zhang, C. & Rana, F. Ultrafast dynamics of defect-assisted electron–hole recombination in monolayer MoS2. Nano lett. 15, 339–345 (2014).

Yu, H., Liu, G.-B., Gong, P., Xu, X. & Yao, W. Dirac cones and Dirac saddle points of bright excitons in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nature comm . 5 (2014).

Mai, C. et al. Many-body effects in valleytronics: Direct measurement of valley lifetimes in single-layer MoS2. Nano lett. 14, 202–206 (2013).

Jiang, J.-H. & John, S. Photonic architectures for equilibrium high-temperature Bose-Einstein condensation in dichalcogenide monolayers. arXiv preprint arXiv: 1412.4788 (2014).

Mouri, S. et al. Nonlinear photoluminescence in atomically thin layered WSe2 arising from diffusion-assisted exciton-exciton annihilation. Phys. Rev. B 90, 155449 (2014).

Okada, M. et al. Direct chemical vapor deposition growth of WS2 atomic layers on hexagonal boron nitride. ACS nano 8, 8273–8277 (2014).

Yan, A. et al. Direct growth of single-and few-layer MoS2 on h-BN with preferred relative rotation angles. Nano lett. 15, 6324–6331 (2015).

Wang, S., Wang, X. & Warner, J. H. All Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth of MoS2: h-BN Vertical van der Waals Heterostructures. ACS nano 9, 5246–5254 (2015).

Kim, M. S. et al. Biexciton Emission from Edges and Grain Boundaries of Triangular WS2 Monolayers. ACS nano (2016).

Plechinger, G. et al. Identification of excitons, trions and biexcitons in single-layer WS2. phys. stat. sol. 9, 457–461 (2015).

Gutiérrez, H. R. et al. Extraordinary room-temperature photoluminescence in triangular WS2 monolayers. Nano lett. 13, 3447–3454 (2012).

Peimyoo, N. et al. Nonblinking, intense two-dimensional light emitter: monolayer WS2 triangles. ACS nano 7, 10985–10994 (2013).

Berkdemir, A. et al. Identification of individual and few layers of WS2 using Raman Spectroscopy. Sci. rep . 3 (2013).

Gao, Y. et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform monolayer WS2 on reusable Au foils. Nature comm . 6 (2015).

Zhao, W. et al. Evolution of electronic structure in atomically thin sheets of WS2 and WSe2. ACS nano 7, 791–797 (2012).

Xu, Z.-Q. et al. Synthesis and transfer of large-area monolayer WS2 crystals: moving toward the recyclable use of sapphire substrates. ACS nano 9, 6178–6187 (2015).

Varshni, Y. P. Temperature dependence of the energy gap in semiconductors. Physica 34, 149–154 (1967).

Mitioglu, A. et al. Optical manipulation of the exciton charge state in single-layer tungsten disulfide. Phys. Rev. B 88, 245403 (2013).

Ross, J. S. et al. Electrical control of neutral and charged excitons in a monolayer semiconductor. Nature comm 4, 1474 (2013).

You, Y. et al. Observation of biexcitons in monolayer WSe2. Nature Phys 11, 477–481 (2015).

Birkedal, D., Singh, J., Lyssenko, V., Erland, J. & Hvam, J. M. Binding of quasi-two-dimensional biexcitons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 672 (1996).

Ye, Z. et al. Probing excitonic dark states in single-layer tungsten disulphide. Nature 513, 214–218 (2014).

Filinov, A., Riva, C., Peeters, F., Lozovik, Y. E. & Bonitz, M. Influence of well-width fluctuations on the binding energy of excitons, charged excitons, and biexcitons in GaAs-based quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 70, 035323 (2004).

Kleinman, D. Binding energy of biexcitons and bound excitons in quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 28, 871 (1983).

Spiegel, R. et al. Polarization-dependent formation of biexcitons in (Zn, Cd) Se/ZnSe quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 55, 9866 (1997).

Shang, J. et al. Observation of excitonic fine structure in a 2D transition-metal dichalcogenide semiconductor. ACS nano 9, 647–655 (2015).

He, Z. et al . Biexciton Formation in Bilayer Tungsten Disulfide. ACS nano (2016).

Shi, H., Pan, H., Zhang, Y.-W. & Yakobson, B. I. Quasiparticle band structures and optical properties of strained monolayer MoS2 and WS2. Phys. Rev. B 87, 155304 (2013).

Chen, J.-H., Jang, C., Xiao, S., Ishigami, M. & Fuhrer, M. S. Intrinsic and extrinsic performance limits of graphene devices on SiO2. Nature nanotech 3, 206–209 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grant-in-aid for Young Scientists A (No. 25708002), Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (No. 25107002, No. 16H00963 and No. 16H00963), challenging Exploratory Research (No. 16H03825), Scientific Research B (No. 16H03825) and Scientific Research S (No. 22225001 and No. 16H06331) from MEXT, Japan, and World Premier International Research Center, Advanced Institute for Materials Research and the Global COE Program in Chemistry, Nagoya University. M.O. thanks the Research Fellowship for Young Scientists supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). We thank S. Masubuchi and T. Machida in the Institute of Industrial Science in The University of Tokyo for their useful advice on mechanical exfoliation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.O. performed the growth and basic spectroscopic characterization of the samples. T.T. and K.W. prepared high quality single crystals of hBN. M.O., Y.M. and K.M. performed time-dependence of PL intensity. R.K. and H.S. designed the study and co-wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Okada, M., Miyauchi, Y., Matsuda, K. et al. Observation of biexcitonic emission at extremely low power density in tungsten disulfide atomic layers grown on hexagonal boron nitride. Sci Rep 7, 322 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00068-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-00068-0

This article is cited by

-

Electronic Structure, Optical Properties, and Potential Applications of n-BN/WS2 (n = 1 to 4) Heterostructures

Journal of Electronic Materials (2021)

-

Dark-exciton valley dynamics in transition metal dichalcogenide alloy monolayers

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Momentum-forbidden dark excitons in hBN-encapsulated monolayer MoS2

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2019)

-

Biexciton fine structure in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides

Nature Physics (2018)

-

Intrinsic excitonic emission and valley Zeeman splitting in epitaxial MS2 (M = Mo and W) monolayers on hexagonal boron nitride

Nano Research (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.