Abstract

Brittle faults and fault zones are important fluid flow conduits through the upper part of Earth’s crust that are involved in many well-known phenomena (e.g. earthquakes, thermal water and gas transport, or water leakage to underground tunnels). The permeability property, or the ability of porous materials to conduct water and gas, is one of the key parameters required in understanding and predicting fluid flow. Although close to a thousand studies have been done, and permeability tested in parts of fault zones, a sytematic summary and database is lacking. This data descriptor is for a multi-disciplinary world-wide compilation and review of bulk and matrix permeability of fault zones: 410 datasets, 521 reviewed sites, 379 locations, >10000 publications searched. The review covers studies of faulting processes, geothermal engineering, radioactive waste repositories, groundwater resources, petroleum reservoirs, and underground engineering projects. The objectives are to stimulate the cross-disciplinary data sharing and communication about fault zone hydrogeology, document the biases and strategies for testing of fault zones, and provide the basic statistics of permeability values for models that require these parameters.

Measurement(s) | permeability |

Technology Type(s) | digital curation |

Factor Type(s) | data source • geographic location |

Sample Characteristic - Environment | geological fault |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11933391

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Geologic evidence of past fluid flow through brittle fault zones is abundant and varied in fault rocks and adjacent altered host rocks1,2,3. The hydrogeological effects on fluid flow in fault zones (e.g. barriers and conduits) have been observed directly at present time. These include thermal springs discharging from faulted crystalline rocks4, faults distrupting fluid flow in sedimentary rocks because of formation offset and clayey fault gouge seal5, or groundwater inflow to underground excavations from fractured rocks in fault zones6,7. Faults or fault zones are now recognized as heterogeneous domains of deformation and associated hydro-mechanical properties from macroscopic to microscopic scale, that may include: single or multi-strand fault core, damage zones of fractured rock, deforming and off-setting the surrounding host rocks or protoliths8,9,10,11. The brittle deformation is also recognized at microscopic or microfracture scale around faults12. Permeability is an important parameter in models of active faults because of fluid involvement in fault geomechanics and earthquake generation13,14,15,16, and temporally enhanced permeability is now directly linked to some types of observed migrating seismicity phenomena along faults17,18. The bulk permeability of the brittle upper crust is only partly known, but there is multiple evidence for fault zones behaving as conductive elements or fluid flow channels through the brittle crust19. The paleo-permeability of faults can be inferred from the properties of fault-hosted ore-deposits20,21. At present time, hydrothermal flow systems in explored geothermal reservoirs often involve permeable faults and thermal fluid convection within fault zones22,23, and both locally and regionally the contrast of fault-host rock bulk permeability is a controlling parameter24. Some of the best (or the most specific) permeability data are from fault-hosted geothermal reservoirs25,26. In sedimentary basins, fault permeability and transmissivity in petroleum reservoirs is intensely studied because of fluid compartmentalization effects27,28, but these effects are also noted in shallow groundwater aquifers29. Fault conduits and barriers to water flow also affect the engineering of underground excavations30, and predictions of contaminant transport.

The published data from fault zones are often isolated from each other in the sub-specialties within the geoscientific disciplines, and not cross-referenced, and continuously diverging into more specialized fields of study. With a growing number of measurements, data compilation becomes difficult, while the geoscience specialization can lead to certain biases in data collection at different scales of measurement31. The multidisciplinary data search is important because most authors in particular geoscientific specialization do not reference works from outside of their field of study, thus creating rather limited reference links that tend to be re-used by subsequent authors.

The compilation and description of these permeability data has several objectives:

-

(1)

improve cross-disciplinary data sharing and communication, and serve as a reference or a guide to the multitude of datasets,

-

(2)

present summary values and site information for as many as possible published datasets and not only selected sites,

-

(3)

enable the statistical exploration of fault zone permeability with structural and geologic parameters for the study sites,

-

(4)

compare the magnitudes of permeability in fault zones and host rocks,

-

(5)

stimulate a critical discussion of this topic, and offer improvements in dataset review and database expansion.

The data descriptor in this article32 is for a database of world-wide test sites in brittle fault zones (test methods, geologic parameters, summarized permeability values), at different geographic locations (Fig. 1). The review was done over seven years, in several iterations, and covered thousands of research items such as journal papers, reports, and conference proceedings published until February 2020. Of the reviewed datasets, 410 passed the initial review, and 111 datasets did not meet the criteria because of lack of published permeability data or unclear data association with fault zones.

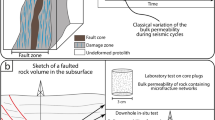

Permeability test data review process diagram. Schematic diagram of the permeability data compilation and review process: (a) search and review of publications (map of the world showing the locations of test sites in this study), (b) hydrogeology & structure at site scale (sketch based on Soultz-sous-Forêts geothermal site modified after ref. 116, (c) fault zone structure and permeability domains (fault zone sketch modified after ref. 117), (d) permeability test scale (drillhole fracture model modified after ref. 118), (e) summary of permeability values in database, (f) technical validation.

Methods

Dataset review process

The concept of “systematic review” and meta-analysis is used in many scientific fields33, and here it was adapted to the hydrogeological data that are both qualitative and quantitative. The search was comprehensive, using multiple databases, and then searching and reviewing all references listed in every publication on the topic of fault zone permeability. The full search of reference lists in all publications was ultimately more systematic and complete, compared to the searches through academic journal or institutional report databases, partly because the titles and keywords were moderately to poorly useful in locating the permeability datasets or supporting documents. The review process is summarized in Fig. 1, and described in the following text sections.

Data sources

The data sources are organized in six categories of “Category of research”, defined loosely by the objectives and motivations of the studies, although many of the studies were multi-disciplinary (Table 1). A list of named fault zones, research sites, geothermal reservoirs, tunnels, mines, outcrops or named drillholes is in Online-only Table 1, to help with document and publication searches for these terms.

Active faults and faulting processes

Approximately 2500 research items were reviewed from structural and hydrogeological studies at 79 locations and 120 datasets. Representative fault zone permeability values were entered for 92 datasets. The database also contains several estimates of paleo-permeability from fault outcrop mineralogy and geometry of sealed fractures, clearly separated from the in-situ test results for present-day permeability. A large number of fault outcrops have been mapped, but relatively few locations have been tested for permeability. The data sources are varied and are listed as follows.

Scientific drilling and outcrop testing:

-

permeability testing of fault rocks on outcrops of active fault zones in metamorphic and plutonic rocks34,35,

-

drilling and in-situ hydraulic testing in parts of active fault zones on continents38,39,40,41,

-

tests in tunnels through parts of active faults42,

-

oceanic drilling program and fault permeability estimates at various locations in the accretionary prisms46,47,

Seismological observations and fluid flow models:

-

permeability of fault conduits inferred from the rate of migration of seismicity near fluid injection locations51,52,

-

permeability and poro-elasticity of host rocks with various effects of faults on fluid flow53,54,

Geothermal reservoirs

The review was initially done on published data from 240 locations, then refined to 169 datasets. However, after the final review, only 115 permeability datasets were clearly fault-related. Particularly useful sources of geothermal data were: the UNU-GTP (United Nations Geothermal Training Programme) in Iceland, the GRC (Geothermal Resources Council) database, and the Stanford University Geothermal Workshop proceedings. The review and permeability summaries were also done for EGS (Enhanced Geothermal System) and HDR (Hot Dry Rock) sites. The enhanced permeability of faults after pressure injection (“fault stimulation”) were stored separately from the values “before stimulation” (natural conditions). In many geothermal fields, the numerical fluid flow models provide a good summary of site-wide bulk permeability, because the models are calibrated to in-situ hydraulic tests. In some cases, original in-situ data were not published, only the site-wide models.

Examples are:

-

geothermal exploration and production in natural hydrothermal areas, including fault-hosted geothermal reservoirs59,60,

-

faulted volcanic and sedimentary reservoirs where the fault conduit-barrier effects are complicated by and permeable stratigraphic units61,62,

-

upflow of thermal waters in natural hot geothermal areas63,

Radioactive waste repositories

The hydrogeological investigations were motivated by characterization of proposed radioactive waste disposal sites, usually located in low-porosity fractured and faulted metamorphic, plutonic, and volcanic rocks (in total 61 datasets). The reports containing the data are searchable through the INIS Repository database of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and from national agencies such as Nagra (Switzerland), SKB (Sweden), Posiva Oy (Finland), JAEA (Japan), AECL (Canada), and the USGS and U.S. Department of Energy, as well as national laboratories. Selected results have also been published previously in scientific journals. The fault structures are often old inactive thrust faults or ductile shear zones or minor faults in the regional setting, because these locations were purposely selected to be in less deformed tectonic blocks. Examples of datasets are:

Groundwater resources and contaminated sites

Aquifer models average large volumes of material, and in a few cases, there are estimates of fault zone conductance (or hydraulic conductivity) for groundwater flow across the fault, calibrated to the observed hydraulic head distributions around the fault zone. More definitive in-situ tests were done at some research sites in combination with tracer tests and detailed flow models. Examples of datasets are:

-

groundwater resources in fractured and faulted metamorphic or plutonic rocks70,

-

groundwater flow in faulted siliciclastic sedimentary rocks71,

-

effects of karst dissolution on fault zones in carbonate rocks72,

Petroleum reservoirs and faulting processes in sedimentary rocks

Many permeability measurements are done routinely by the petroleum industry, and the search results were from publicly available articles and reports only. The published data are largely from fault zones exposed on outcrops, and less from drilled study sites. Examples are:

Engineering projects

This section relies upon reports and papers on hydraulic tests and observations in long tunnels, mines, and dams constructed in various rock types at depths up to 2 km. The groundwater inflow to tunnels from fault zones can provide estimates of transmissivity and bulk permeability. Examples of datasets are:

-

hydrogeology of fault zones in deep transportation tunnels, tested using drillholes78,

-

estimates of fault zone and host rock permeability from water inflow rates along tunnels79,

-

inflows from faults to mines80.

The locations of reviewed test sites on world maps are plotted in Fig. 2. The geographic coordinates were either reported in the original publications, or, were estimated from published maps on figures in those publications. For each study site, the location was checked in Google Maps or Google Earth applications, compared to the descriptions in published reports or papers. A note was entered in the database about location uncertainty.

Locations of world-wide fault zone permeability test sites. (a) Locations with available bulk and matrix permeability, (b) datasets from studies on active faults and faulting processes, (c) geothermal reservoirs, (d) radioactive waste repository studies, (e) groundwater resources and contaminated sites, (f) petroleum reservoirs and faults in sedimentary rocks, and (g) engineering projects.

Geologic parameters

As a broad overview, all test sites are in the upper part of the brittle Earth’s crust, in both the crystalline “basement” rocks and in the overlying sedimentary basins or volcanic rocks. The depth intervals of tests in fault zones can be visualized along a schematic cross-section along the geographic longitude (Fig. 3), where all the data are projected on the section and shown as elevation above sea level or as depth below ground or sea floor. The depth range of in-situ tests in drillholes or tunnels is from 0 to about 9 km depth below ground on land, and to about 1 km depth below sea floor at ocean drilling sites.

A brief summary text of the local geology and regional context is included in the database. The host rocks were classified into categories by their overall rock type and not particular mineralogical characteristics:

-

“Siliciclastic (coarse)” category (n = 89) includes the sandstone and interlayered sandstone with fine grained rocks. A sub-category was given for unlithified siliciclastic rocks, and a category for tests in deformation bands (reviewed in detail by other authors81).

-

“Mudrock” category (n = 30) here refers to the fine-grained siliciclastic rocks82,83 clay, silt, claystone, mudstone, clay-rich siltstone, shale, and any argilliceous rocks). Marl rock and mixed mud-carbonate rocks, that have relatively low strength and smear when faulted, were placed in the mudrock category due to their hydro-geomechanical properties84.

-

“Carbonates & evaporites” category (n = 47) is for the test sites mainly in limestone or dolomite, often metamorphosed to some degree. At a few locations the dolostones are interbedded with anhydrites and other evaporites or marble. A few outcrops were in high-porosity grainstones.

-

“Volcaniclastic” category (n = 25) has the test data mainly from tuff rocks and tuffaceous sediments. There is a large variability in hydraulic properties of tuffs, depending on their cementation and alteration85. In volcanic areas, tuffaceous rocks are usually interlayered with andesitic or basaltic layers, thus in some cases both categories of volcaniclastic and volcanic igneous were marked as present.

-

“Volcanic igneous” category (n = 73) is for the intrusive and extrusive volcanic rocks, although these can be interlayered with volcaniclastics and other sediments.

-

“Plutonic” category (n = 137) here is for the granitic and granodioritic rocks from a wide variety of data sources: drilling in large batholiths (e.g. exposed in mountain massifs) or at smaller intrusions at some geothermal fields.

-

“Metamorphic” category (n = 126) is a large group of metamorphic rocks that are found in the basement rock at most of the study sites.

It should be noted that host rocks around faults also contain an agglomeration of deformations that may not be related to the presently tested fault zone (e.g. sparse natural fractures of various origin, intrusive dykes, stratigraphic or lithologic contacts and associated fracturing, old ductile deformation that is now part of the host rock for the brittle fault, etc.). The host rocks that are considered here are with respect to the now (in most cases exhumed) brittle fault zones. This review does not cover ductile shear zone permeability or their protoliths at the time of shear zone activity.

The structural geology was reviewed for each site and the available fault size parameters were summarized: fault displacement and throw, length, width of fault core and damage zone, and whole fault zone width. The total displacement was rarely reported, and it was found at about 25% of the sites. The total displacement for a fault zone is often accumulated among many fault segments within fault zones. Fault throw, or dip-slip displacement, was entered separately. Fault length was either for the whole fault zone or for fault segment in the fault zone (if tested specifically). The fault length, where not reported in publications, was estimated in this review from the geologic maps and figures in some cases. The best mapped widths of fault zone components were the fault cores. Fault core width varied greatly from cm to multi-meter scale at many study sites, and many of the fault zones had multiple fault cores (multiple fault strands). The closest fault core to the one tested for permeability was reported here. In most cases, there was no specific fault core tested, and thus the widest reported fault core width was entered to this database. The width of fault damage zone is difficult to define at the majority of study sites. Fault zone widths are only certainly known across exposed fault outcrops or along tunnel section. The width value can be viewed as a sample from a width population along the fault.

Review of permeability test methods

In each case study, the permeability estimates were associated with particular test methods in the database. This is coded by categorical variables (1 = yes, blank = no) and text summaries. The first group of methods involves some direct estimation of permeability through Darcy’s Law, by inducing a pressure gradient and fluid flow through porous media. The second group is for other estimation methods that require more assumptions about how the observed response variables relate to permeability of porous media. Most of the methods apply to present-day permeability, with exception of the geochemical/mineralogical estimation of paleo-fluid flux (column 64). The method of fracture aperture empirical laws (column 61) was also in some cases applied to mineral-filled (sealed) fractures to estimate paleo-permeability that is obviously different from present permeability of such rock.

The scale of permeability tests is important to differentiate, because the rock matrix permeability can be 2 to 4 orders of magnitude smaller than the bulk permeability of the same rock that includes the macroscopic fracture networks in low-porosity brittle rocks86,87. In high-porosity weak rocks the fractures add some permeability component88, but the fluid-induced transient fracture dilation effects are also important. The relative effect of macroscopic fractures become more important in rocks of lower porosity and larger density89. In this compilation, the matrix permeability refers to tests on small (few cm size) rock samples or rock outcrop spots, but does not include macroscopic fractures at scales >0.1 meter. The bulk permeability refers to an estimate of total permeability from in-situ tests (e.g. hydraulic tests in drillole intervals) at length scales of meters to 100’s meters usually. The bulk permeability includes the effects of connected flow channels within macroscopic fracture networks. The terminology is widely used in hydrogeology and structural geology90,91,92.

The matrix permeability is determined directly from tests that induce some water or gas flow across the samples (laboratory permeameter apparatus), or into spots on samples or rock outcrops (permeameter probes). Macroscopic fracture channels or macropores were sometimes tested on whole drillcore samples. The following text is a list of test methods, and include the number of datasets in brackets (not the individual tests or samples). Additional references are given with examples from fault zones, if not already listed in the methods section.

The direct permeametry estimation methods are:

-

Core plugs or smaller samples tested inside laboratory permeameters under confining pressure in order to seal the sample, or purposely at high confining pressure to simulate a larger effective depth than the original sample depth (n = 103 datasets),

-

Whole drill-core pieces with faults tested inside permeameters93 (n = 36),

-

Outcrop transects using gas injection or air extraction at test spots (transient or steady state flow rate), including spots on drillcore pieces94 (n = 31),

Indirect matrix permeability estimation methods are:

-

Microfracture or pore geometry95 relations that link the porosity to permeability, or the microfracture size to permeability (n = 8),

-

Geochemical/mineralogical methods for estimating the required paleo-permeability96 (matrix or bulk, depending on context) of the main fluid flow conduits from larger depths (n = 2),

Bulk permeability direct testing methods, in column order from the database are:

-

Infiltration or exfiltration at the outcrop97, where water is injected or infiltrated or removed from the outcrop (n = 4),

-

Single borehole tests are the most extensively used methods in fault zones and host rocks (injection, discharge, slug or pulse tests)98,99,100 (n = 206),

-

Tidal analysis of the water pressure fluctuations in drillholes as a response to the solid earth tides or ocean tides101 (n = 10),

-

Barometric fluctuations in the unsaturated zone to estimate air flow rate along the fault zones102 (n = 1),

-

Cross-borehole tests in fractured zones, where the fracture networks are tested directly between two drillholes38,103 (n = 39),

-

Pumping or injection tests and monitoring of pressure responses in other drillholes (interference tests)70,104,105 (n = 139),

Numerical flow models are used at almost all research and industrial sites, and in this review the bulk permeabilities of fault zones and host rocks were useful because the original data (individual well test results) were often not published. Measurements that help calibrate numerical flow models were described for some test sites:

-

Water inflows/outflows in the drillholes (circulation loss or well feed points), are used as a supporting information in interpretations of well tests (n = 39),

-

Reservoir production/reinjection data (pressure, fluid flow rate, and temperature), used for the numerical flow model calibration (n = 28),

-

Tracer tests to estimate the porosity and connectivity of the groundwater flow system97,105 (n = 27),

-

Spring water or gas flow from faults as a supporting evidence for fluid flow in fault zones106 (n = 13),

Other indirect permeability estimation methods:

-

Empirical laws for fracture aperture and spacing, used to estimate the bulk permeability107 (n = 7),

-

Grout injection volume patterns across a fault zone108 (n = 3),

-

Geophysical methods in drillholes to estimate the permeability (e.g. tube wave reflections)109 (n = 3),

-

Microseismicity hypocenter migration over time, where the bulk permeability of presumed fluid flow conduits along fault zones is calculated from the estimate of hydraulic diffusivity110,111 (n = 15),

-

Thermal water upflow velocity that is estimated from the vertical temperature gradient and an estimate of permeability from thermal water outflow rate112 (n = 2).

Depths of tests

In-situ tests of bulk permeability

All in-situ bulk permeability values are assigned a vertical depth below the ground surface on land (or sea floor for oceanic drill sites). For depth intervals, both the maximum depth and minimum depths are specified (columns 75 to 76). For single depth points (not an interval), only the maximum depth is given. The average depth (column 77) here means the mid-point depth between the maximum and minimum depth. It equals the maximum depth for single depth points. In geothermal reservoir models, tunnels, or large research facilities with many drillholes, the depth was given as a range of results from the fault zone (as described in published materials). In mountainous terrain, the average depth below ground was estimated from geologic cross-sections and the published test depths.

Matrix permeability from outcrops and samples

For fault zone outcrops on the ground surface, for data storage and graphing purposes a 1 m depth is entered as the maximum depth. This allows to plot the permeabilities of outcrops and in-situ data from depths on logarithmic depth scales (instead of 0 m depth of outcrop). For drillcore samples, the depth of each sample was entered as the maximum depth only.

Effective depth of matrix permeability for rock samples

A depth value must be associated with the permeability results, but in many laboratory tests on rock samples a high confining pressure (and effective pressure) is often used that acts on the porous media and compresses it. The matrix permeability tends to descrease with increasing confining pressure (pore space and microfracture compaction), and does not recover completely during depressurization113,114. For this review, the matrix permeability values are taken at the smallest reported confining pressures (columns 82 and 83 give the range) in the initial pressurizing path before sample compaction, or as recommended by the authors of publications. The “effective” depth value (column 88) is not the depth of original rock sample (drillcore or outcrop). Effective depth depends on the assumed average pressure gradients in the Earth’s brittle crust, assuming hydrostatic conditions and average pressure gradients115 in Eq. (1):

where Deff is the effective depth of permeability sample (km), Peff is the effective confining pressure (MPa) on test sample (see column 87), ΔPlith is the lithostatic pressure gradient (MPa/km), ΔPhydro is the hydrostatic pressure gradient (MPa/km). The assumed average lithostatic pressure gradient was 23 MPa/km and a hydrostatic gradient of 10 MPa/km, thus an effective pressure gradient 13 MPa/km. If the sample drilled depth (or outcrop 0 depth) is much greater (>1 km) than the effective depth, the value in column 89 is tagged as 1. These values can be adjusted by the database users if the site-specific pressure gradients are known more precisely.

Permeability values

The permeability data were separated by test scale category (matrix and bulk). The test results that were originally reported in the literature as transmissivity, hydraulic conductivity, or permeability thickness, were converted to m2 permeability units. Logarithms of permeability (log10 m2), were also calculated to aid in graphing of permeability vs. depth, and for further statistical analysis.

Representative permeability estimate

Only the summary (representative) values of permeability for datasets are reported in this database, not all individual test points in large datasets from the original publications. This database does not compile all raw data and all test spots on outcrops, multiple drillhole test intervals, etc. For each dataset, the representative permeability values are recorded. At 81% of the study sites there is only one permeability test result from in-situ test, and usually only one estimate of bulk permeability in the fault zone. Multiple datasets of fault zone permeability were defined at 19% of the sites, separated for different reasons: distinctly different fault zones, different host rock along the same fault zone, large depth separation of groups of in-situ tests, or statistical and model summaries of different fault sets as defined by the authors of original publications.

-

The representative permeability was in the majority of cases the only value available.

-

Where a larger amount of drilling has been done, the review was focussed on finding the representative bulk permeability values that had been already reported by the original authors. This review uses the published conceptual models and statistics and does not re-analyse the data.

-

Where only a few test values were taken, the more recent or higher-quality results were used. Given a choice of two permeability estimates, or two clusters of permeability values in original publications, the maximum value was chosen as representative, and the lower estimate was entered separately in the database.

-

The summaries of matrix permeability were provided, not individual test measurements (or other raw data).

Low estimate of permeability

Since many drillholes tend to miss the most permeable conduits in fault zones, and some fault rocks from fault core are relatively more lithified or re-cemented, another summary value is the “low estimate” of permeability. In cases of more than one data value (e.g. many drillholes or points along outcrop transect), the low estimate of matrix permeability is as reported on published graphs or tables by other authors, or the average for a cluster of values in the low range of permeability for that site. For example, along an outcrop, a typical low permeability value in the damage zone, but higher than the host rock “background” value, was summarized.

Assignment of permeability to fault zone structural domain

The matrix permeability on samples or outcrop spots was assigned either to the fault core, the fault damage zone, or the host rock, as described in the published sources. It must be noted that in drillcore or core plug samples, the damage zone contains macroscopic fractures that are nearly all sealed by the cementing minerals, and the microfractures may be also partially open. Aside from the obvious sampling and scale effects of these tests, the locations within the fault zone were usually clear. The values were entered to columns 90–91 (fault core), 94–95 (damage zone), 100–101 (host rock).

The bulk permeability from in-situ tests (drillholes, tunnels, etc.) is the sum of contributing flow paths, dominated by macroscopic flow channels or highly porous rocks, in some rock volume that is influenced by fluid flow of the in-situ test. The permeability values were assigned as follows:

-

host rock: in-situ tests away from the fault core or fault damage zone (values in columns 102–103),

-

fault core zone: clear evidence that the fault core was isolated in-situ, or that it contributed most of the fluid flow (values in columns 92–93),

-

fault zone* refers to some part of fault zone in general (except fault core where isolated in the test interval): values entered to columns 96–97, and then explained by two categorical variables (columns 98 and 99),

-

if the tested rock volume is only within the fault damage zone, column 98 has a value 1 and column 99 has a blank value

-

if the tested rock volume is within parts of the fault damage zone and may include the main fault core zone, whether or not the fault core contributes significantly (positively or negatively) to the bulk permeability, column 99 has a value 1 and column 98 has a blank value

Permeability ratios

Ratios were calculated between bulk permeabilities of the fault zone*, the fault core, and the host rock (protolith), as in Eq. (2):

where k1 and k2 are permeability values in m2 units. For example, k2 is usually the host rock permeability and k1 is the fault zone permeability. This ratio can be used to quantify the “conduit” magnitude or “barrier” magnitude of a fault zone, but both the fault zone (or a component of fault zone) and the host rock permeability must be known at the same location. Host rock from distant locations or regional averages cannot be used because the range of permeability values is too wide regionally. In other words, the data must be matched to the same fault zone or part of fault zone at the same location, ideally along the same drillhole or outcrop transect, but adjacent drillholes may be used. The measurement scale must also be consistent (e.g. cannot use matrix permeability for host rock and bulk permeability for fault zone). Both values must be either matrix permeability or bulk permeability, and ideally tested with similar methods and affecting similar rock volumes.

The following ratios were estimated for permeabilities for the best representative value and the low estimate:

-

log(bulk k Fault Zone/bulk k Host Rock) (columns 104–105)

-

log(matrix k Fault Core/matrix k Host Rock) (columns 106–107)

-

log(bulk Fault Core/bulk Host Rock) (columns 108–109)

Data records

The data repository items32 at figshare contain a database with 121 different data fields (or columns), as described in Online-only Table 2. In the spreadsheet version (Microsoft Excel.xlsx file), the first row contains the labels or headings for the columns. The.pdf files contain the printed-out versions of the database and the list of selected references. The following additional notes refer to the spreadsheet table.

Columns 1 to 13 contain information about the study sites and their locations. The first column has the “Dataset number”. Fault zone sites at different geographic localities differ by whole integer numbers. Where there is more than one dataset at a fault zone test site, the dataset number is incremented by the first decimal digit. For example, one site with three datasets on fault zone permeability may have dataset numbers 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, and next site with one dataset is 2. The order of Dataset numbers is by “Category of research” (column 2), next alphabetically by “Country” (column 4), and lastly by “Site name” (column 3). The geographic coordinates are latitude and longitude for the test site (not individual test intervals). Ground surface elevations also apply to whole study sites (e.g. elevation at well-head, topographic elevation above geothermal reservoir or tunnel, sea floor surface at oceanic drillhole, etc.). Sub-sea drilling locations have elevations below sea level (negative values). The elevations are rounded off to match the value uncertainty.

The database columns 14 to 24 describe the host rock type and local geology, as brief text descriptions and categorical variables (1 = yes or present, and blank otherwise) for host rock types. The fault types and sizes are summarized, where known, in columns 25 to 43. There is a referenced text summary about known fault structures. The fault types are categorized (n = counts of test sites): normal faults (n = 180), reverse faults (n = 32), normal-oblique faults (n = 32), strike-sip faults (n = 30), faults that run along dykes or wide veins (n = 30). For some cases, the fault type or size could not be verified at this time. Some faults are simply categorized as high or low angle fault, or a dip value is given (or dip value range). The fault size parameters are in columns 37 to 43. These include any known values of the fault throw, displacement, length, width of fault core, width of damage zone, or width of whole fault zone.

Permeability test methods are summarized and categorized in columns 44 to 67. A summary text (column 44) is referenced to publications, and with notes about permeability unit conversions. The available permeability values are described in text in column 68, with references to data sources and methods, and notes about any measurement unit conversions. The next column 69 has the result of “Initial review pass” (1 = yes). For selected sites there are comments in column 70 about the review result. Datasets from tests on rock outcrops are tagged in column 72, and those outcrops that have data from fault core or fault damage zone are tagged in column 73. In-situ test results from some depth that represent fault zones are indicated in column 74.

Technical validation

Qualitative assessment of test site and results

During this review of the published datasets, the conceptual models of fault’s hydrology were compared with the consistency of the results of hydraulic tests in fault zones, and parameters used in calibrated numerical flow models. This qualitative review focussed on several aspects of published data:

-

clarity and detail of site descriptions and data analysis methods,

-

data quantity (e.g. number of drillholes and tests),

-

test methods and scale of tests (matrix vs. bulk permeability),

-

site-wide conceptual models, including calibrated numerical groundwater flow models,

-

detail of structural mapping and analysis,

-

permeability test location within the fault zone or host rocks.

The records that did not pass the review are still kept in the database, in a separate table, because of other useful information about the site. The dataset numbers continue between the two tables, and when merged, are consistent and sequential for the whole database. Perhaps the next review of world-wide permeability test sites may clarify the questions or provide more data.

Uncertainty of fault size parameters

The fault size estimates are uncertain due to the measurement limitations (e.g. covered outcrops, variable scale of measurement from macroscopic to microscopic). It is often not known what exact fault segments or strands, or overlapping fault damage zones, in a larger fault zone contribute to the bulk permeability in each in-situ test. During this review, a statistical exploration was performed of the structural data to compare the fault displacement, length, fault core and fault zone width, and fault type. The apparent outliers were reviewed again.

Uncertainty of permeability values

The uncertainty of matrix permeability values depends on the test method, and in particular the ability to seal the probe to outcrop or rock sample, the type of fluid used, or sample conditions (damage). Measurement accuracy in laboratory permeameters is usually adequate, but tests on natural fault outcrops are usually not verified for probe seal or gas leakage. Reported values are typically in a range of a factor of 2 to 5 for particular test site.

The uncertainty of bulk permeability values can be attributed to methods of in-situ testing, assumptions used in the interpretation of data, and the problems with sampling of highly heterogeneous rocks and fracture networks. For individual well tests, the parameters may be fitted to give bulk permeability within single decimal value, but the results for whole sites are usually considered to be within an order of magnitude of actual conditions. The rock volume that contains a fault zone is many orders of magnitude larger than the volume tested for permeability, thus it is expected that the most permeable or conductive parts may be missed. It is difficult to quantify the uncertainty in bulk permeability of a fault zone. The difference between the representative estimate and the low estimate in this review gives some indication about this uncertainty.

The heterogeneity of hydraulic properties in fault zones cause practical difficulties of separating parts of fault zones for in-situ tests, and interpretation of well-test data. The specific in-situ data on fault cores (fault core zones) is particularly limited, thus the contributions of fault cores to the total bulk permeability in fault zones cannot be estimated at many test sites.

References

Newhouse, W. H. Ore Deposits As Related To Structural Features. (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1942).

Sibson R. H. In Earthquake Prediction: An International Review Vol. 4 (eds. Simpson, D. W. & Richards, P. G.), https://doi.org/10.1029/ME004 (American Geophysical Union, 1981).

Kerrich, R. Fluid infiltration into fault zones: chemical, isotopic, and mechanical effects. Pure Appl. Geophys. 124, 225–268 (1986).

Bryan, K. Classification of springs. J. Geol. 27, 522–561 (1919).

Meinzer, O. E. The Occurrence Of Ground Water In The United States With A Discussion of Principles. (The University of Chicago, Illinois, 1923).

Louderback, G. D. In Application of Geology To Engineering Practice Vol. 1, (Geological Society of America, Berkeley 1950).

Fujita, K., Ueda, K. & Gomi, M. In Tunneling Under Difficult Conditions (ed. Kitamura, I.), https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(80)90362-9 (Pergamon Press, Tokyo 1978).

Seeburger, D. A. Studies of Natural Fractures, Fault Zone Permeability, and a Pore Space-Permeability Model. (Stanford University, California, 1981).

Chester, F. M. & Logan, J. M. Implications formechanical properties of brittle faults from observations of the Punchbowl fault zone, California. Pure. Appl. Geophys. 124, 80–106 (1986).

Scholz, C. H. & Anders, M. H. In The Mechanical Involvement of Fluids in Faulting (eds. Hickman, S. H., Sibson, R. & Bruhn, R.), USGS Open File Report 94–228 (U.S. Geological Survey, 1994).

Caine, J. S., Evans, J. P. & Foster, C. B. Fault zone architecture and permeability structure. Geology 24, 1025–1028 (1996).

Faulkner et al. A review of recent developments concerning the structure, mechanics and fluid flow properties of fault zones. J. Struct. Geol. 32, 1557–1575 (2010).

Haneberg, W. C., Mozley, P. S., Moore, J. C. & Goodwin, L. B. Faults and Subsurface Fluid Flow in the Shallow Crust. Geophysical Monograph 113, (AGU, 1999).

Townend, J. & Zoback, M. D. How faulting keeps the crust strong. Geology 28, 399–402 (2000).

Gratier, J.-P., Favreau, P. & Renard, F. Modeling fluid transfer along California faults when integrating pressure solution crack sealing and compaction processes. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 2104 (2003).

Yamashita, T. & Tsutsumi, A. Involvement of Fluids in Earthquake Ruptures, Field/Experimental Data and Modeling. (Springer Japan KK, 2018).

Nur, A. & Booker, J. R. Aftershocks caused by pore-fluid flow? Science 175, 885–887 (1972).

Miller, S. A. et al. Aftershocks driven by a high‐pressure CO2 source at depth. Nature 427, 724–727 (2004).

Ingebritsen, S. E. & Manning, C. E. Permeability of the continental crust: dynamic variations inferred from seismicity and metamorphism. Geofluids 10, 193–205 (2010).

Ingebritsen, S. E. & Appold, M. S. The physical hydrogeology of ore deposits. Econ. Geol. 107, 559–584 (2012).

Cox, S. F. Injection-driven swarm seismicity and permeability enhancement: implications for the dynamics of hydrothermal ore systems in high fluid-flux, overpressured faulting regimes. Econ. Geol. 111, 559–587 (2016).

Kassoy, D. R. & Zebib, A. Convection fluid dynamics in a model of a fault zone in the earth’s crust. J. Fluid Mech. 88, 789–792 (1978).

Bodvarsson, M. G. & Benson, M. Well Test Data from Geothermal Reservoirs. Report LBL-13295 (Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, California, 1982).

Gottardi, R., Kao, P.-H., Saar, P.-H. & Teyssier, C. Effects of permeability fields on fluid, heat, and oxygen isotope transport in extensional detachment systems. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys. 14, 1493–1522 (2013).

Goko, K. Structure and hydrology of the Ogiri feld, West Kirishima geothermal area, Kyushu, Japan. Geothermics 29, 127–149 (2000).

Sausse, J., Fourar, M. & Genter, A. Permeability and alteration within the Soultz granite inferred from geophysical and flow log analysis. Geothermics 35, 544–560 (2006).

Shipton, Z. K., Evans, J. P., Robeson, K. R., Forster, C. B. & Snelgrove, S. Structural heterogeneity and permeability in faulted eolian sandstone—implications for subsurface modeling of faults. AAPG Bull. 86, 863–883 (2002).

Jolley, S. J., Fisher, Q. J., Ainsworth, R. B., Vrolijk, P. J. & Delisle, S. Reservoir Compartmentalization. Geol. Soc. S. Pub. 347, 1–8 (2010).

Bense, V. F., Gleeson, T., Loveless, S. E., Bour, O. & Scibek, J. Fault zone hydrogeology. Earth-Sci. Rev. 127, 171–192 (2013).

Masset, O. & Loew, S. Hydraulic conductivity distribution in crystalline rocks, derived from inflows to tunnels and galleries in the central Alps, Switzerland. Hydrogeol. J. 18, 863–891 (2010).

Scibek, J., Gleeson, T. & McKenzie, J. M. The biases and trends in fault zone hydrogeology conceptual models: global compilation and categorical data analysis. Geofluids 16, 782–79 (2016).

Scibek, J. Multidisciplinary database of permeability of fault zones and surrounding protolith rocks at world-wide sites. figshare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10052033.v2 (2020).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6, e1000097 (2009).

Wibberley, C. A. J. & Shimamoto, T. Internal structure and permeability of major strike-slip fault zones: The Median Tectonic Line in Mie Prefecture, Southwest Japan. J. Struct. Geol. 25, 59–78 (2003).

Rempe, M. et al. The relationship between microfracture damage and the physical properties of fault-related rocks: The Gole Larghe Fault Zone, Italian Southern Alps. J. Geoph. Res-Sol. Ea. 123, 7661–7687 (2018).

Okubo, C. H. Spatial distribution of damage around faults in the Joe Lott Tuff Member of the Mount Belknap Volcanics, Utah: A mechanical analog for faulting in pyroclastic deposits on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 117, E08003 (2012).

Walker, R. J., Holdsworth, R. E., Imber, J., Faulkner, D. R. & Armitage, P. J. Fault zone architecture and fluid flow in interlayered basaltic volcaniclastic-crystalline sequences. J. Struct. Geol. 51, 92–104 (2013).

Doan, M. L., Brodsky, E. E., Kano, Y. & Ma, K. F. In situ measurement of the hydraulic diffusivity of the active Chelungpu Fault, Taiwan. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L16317 (2006).

Karasaki, K., Onishi, T. & Wu, Y.-S. Development of Hydrologic Characterization Technology of Fault Zones. (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 2014)

Kitagawa, Y. & Kano, Y. Changes in permeability of the Nojima fault damage zone inferred from repeated water injection experiments. Earth Planets Space 68, 185 (2016).

Townend, J. et al. Petrophysical, geochemical, and hydrological evidence for extensive fracturemediated fluid and heat transport in the Alpine Fault’s hanging-wall damage zone. Geochem. Geophy. Geosy. 18, 4709–4732 (2017).

Nohara, T., Tanaka, H., Watanabe, K., Furukawa, N. & Takami, A. In situ hydraulic tests in the active fault survey tunnel, Kamioka Mine, excavated through the active Mozumi-Sukenobu Fault Zone and their hydrogeological significance. Island Arc 15, 537–545 (2006).

Evans, J. P., Forster, C. B. & Goddard, J. V. Permeability of Fault related Rocks, and Implications for Hydaulic Structure of Fault Zones. J. Struct. Geol. 19, 1393–1404 (1997).

Lockner, D. et al. Geometry of the Nojima Fault at Nojima-Hirabayashi, Japan – I. A Simple Damage Structure Inferred from Borehole Core Permeability. Pure Appl. Geophys. 166, 1649–1667 (2009).

Morrow, C. A., Lockner, D. A., Moore, D. E. & Hickman, S. Deep permeability of the San Andreas Fault from San Andreas Fault Observatory at Depth (SAFOD) core samples. J. Struct. Geol. 64, 99–114 (2014).

Screaton, E., Carson, B., Davis, E. & Becker, K. Permeability of a decollement zone: Results from a two-well experiment in the Barbados accretionary complex. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 21403–21410 (2000).

Saffer, D. M. The permeability of active subduction plate boundary faults. Geofluids 15, 193–215 (2015).

Juhlin, C. & Sandstedt, H. Storage Of Nuclear Waste In Very Deep Boreholes: Feasibility Study And Assessment of Economic Potential. Technical Report 89–39 (SKB, Stockholm, 1989).

NEDRA. Characterization Of Crystalline Rocks In Deep Boreholes. The Kola, Krivoy Rog And Tyrnauz Boreholes. Technical Report 92–39 (SKB, Stockholm, Sweden, 1992).

Huenges, E., Erzinger, J., Kuck, J., Engeser, B. & Kessels, W. The permeable crust: Geohydraulic properties down to 9101 m depth. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 18255–18265 (1997).

Shapiro et al. Fluid induced seismicity guided by a continental fault: Injection experiment of 2004/2005 at the German Deep Drilling Site (KTB). Geoph. Res. Lett. 33, L01309 (2006).

Goebel et al. Wastewater disposal and earthquake swarm activity at the southern end of the Central Valley, California. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 1092–1099 (2016).

Chang et al. Operational and geological controls of coupled poroelastic stressing and pore-pressure accumulation along faults: Induced earthquakes in Pohang, South Korea. Sci. Rep. 10, 2073 (2020).

Talwani, P., Chen, L. & Gahalaut, K. Seismogenic permeability, ks. J. Geophys. Res. 112, B07309 (2007).

Chen, X., Shearer, P. M. & R. E. Abercrombie, R. E. Spatial migration of earthquakes within seismic clusters in Southern California: Evidence for fluid diffusion. J. Geophys. Res. 117, B04301 (2012).

Okada et al. Hypocenter migration and crustal seismic velocity distribution observed for the inland earthquake swarms induced by the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake in NE Japan: implications for crustal fluid distribution and crustal permeability. Geofluids 15, 293–309 (2015).

Evans, K., Genter, A. & Sausse, J. Permeability creation and damage due to massive fluid injections into granite at 3.5 km depth, at Soultz: 1. Borehole observations. J. Geophys. Res. 110, B04203 (2005).

Ladner, F. & Häring, M. O. Hydraulic characteristics of the Basel 1 Enhanced Geothermal System. Geoth. Res. T. 33, 199–203 (2009).

Axelsson, G. & Bodvarsson, G. Analysis of production data from fractured liquid dominated geothermal reservoirs in Iceland. Geoth. Res. T. 11, 573–580 (1987).

Milicich, S. D., Clark, J. P., Wong, C. & Askari, M. A review of the Kawerau Geothermal Field, New Zealand. Geothermics 59, 252–265 (2016).

Stimac, J., Nordquist, G., Suminar, A. & Sirad-Azwar, L. An overview of the Awibengkok geothermal system, Indonesia. Geothermics 37, 300–331 (2008).

Pope, E. C., Bird, D. K., Arnorsson, S. & Giroud, N. Hydrogeology of the Krafla geothermal system, northeast Iceland. Geofluids 16, 175–197 (2016).

Muraoka, H., Sakaguchi, K., Nakao, S. & Kimbara, K. Discharge temperature–discharge rate correlation of Japanese hot springs driven by buoyancy and its application to permeability mapping. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L10405 (2006).

Bossart, P., Hermanson, J. & Mazurek, M. Äspö Hard Rock Laboratory Analysis of Fracture Networks Based on the Integration of Structural and Hydrogeological Observations on Different Scales. Technical Report TR-01-21 (SKB, Stockholm, 2001).

Vaittinen, T., Ahokas, H., Nummela, J. & Paulamäki, S. Hydrogeological Structure Model Of The Olkiluoto Site – Update In 2010. Working Report 2011–65 (POSIVA OY, Finland, 2011).

Marschall, P. et al. Synthesis Of Hydrogeological Investigations At The Mont Terri Site (Phases 1 To 5). Technical Report TR 2001-02 (Mount Terri Project, 2003).

Ishii, E. Predictions of the highest potential transmissivity of fractures in fault zones from rock rheology: Preliminary results. J. Geophys. Res-Sol. Ea. 120, 2220–2241 (2015).

Sweetkind, D. S. & Drake, R. M. II Characteristics Of Fault Zones In Volcanic Rocks Near Yucca Flat, Nevada Test Site, Nevada. Open–File Report 2007–1293 (U.S. Geological Survey, 2007).

Gutmanis, J. C., Lanyon, G. W., Wynn, T. J. & Watson, C. R. Fluid flow in faults: a study of fault hydrogeology in Triassic sandstone and Ordovician volcaniclastic rocks at Sellafield, north-west England. P.Yorks. Geol. Soc. 52, 159–175 (1998).

Roques et al. Hydrological behavior of a deep sub-vertical fault in crystalline basement and relationships with surrounding reservoirs. J. Hydrol. 509, 42–54 (2014).

Cilona, A., Aydin, A. & Johnson, N. M. Permeability of a fault zone crosscutting a sequence of sandstones and shales and its influence on hydraulic head distribution in the Chatsworth Formation, California, USA. Hydrogeol. J. 23, 405–419 (2015).

Bauer, H., Schröckenfuchs, T. C. & Decker, K. Hydrogeological properties of fault zones in a karstified carbonate aquifer (Northern Calcareous Alps, Austria). Hydrogeol. J. 24, 1147–1170 (2016).

Antonellini, M. & Aydin, A. Effect of faulting on fluid flow in porous sandstones: petrophysical properties. AAPG Bull. 78, 355–377 (1994).

Flodin, E. A. Structural evolution, petrophysics, and large-scale permeability of faults in sandstone, Valley of Fire, Nevada. (Stanford University, California, 2003).

Micarelli, L., Benedicto, A. & Wibberley, C. A. J. Structural evolution and permeability of normal fault zones in highly porous carbonate rocks. J. Struct. Geol. 28, 1214–1227 (2006).

Michie, E. A. H. & Haines, T. J. Variability and heterogeneity of the petrophysical properties of extensional carbonate fault rocks, Malta. Petrol. Geosci. 22, 136–152 (2016).

Fisher, Q. J. & Knipe, R. J. The permeability of faults within siliciclastic petroleum reservoirs of the North Sea and Norwegian Continental Shelf. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 18, 1063–1081 (2001).

Lutzenkirchen, V.H. Structural geology and hydrogeology of brittle fault zones in the central and eastern Gotthard Massif, Switzerland. (ETHZ, Zurich, 2002).

Masset, O. & Loew, S. Quantitative hydraulic analysis of pre-drillings and inflows to the Gotthard Base Tunnel (Sedrun Lot, Switzerland). Eng. Geol. 164, 50–66 (2013).

Achtziger-Zupančič, P., Loew, S. & Hiller, A. Factors controlling the permeability distribution in fault vein zones surrounding granitic intrusions (Ore Mountains/Germany). J. Geophys. Res-Sol. Ea. 122, 1876–1899 (2017).

Ballas, G., Fossen, H. & Soliva, R. Factors controlling permeability of cataclastic deformation bands and faults in porous sandstone reservoirs. J. Struct. Geol. 76, 1–21 (2015).

Loucks, R. G., Reed, R. M., Ruppel, S. C. & Hammes, U. Spectrum of pore types and networks in mudrocks and a descriptive classification for matrix-related mudrock pores. AAPG Bull. 96, 1071–1098 (2012).

Rutter, E., Mecklenburgh, J. & Taylor, K. Geomechanical and petrophysical properties of mudrocks: introduction. Geol. Soc., London, S. Pub. 454, 1–13 (2017).

Ishii, E., Sanada, H., Funaki, H., Sugita, Y. & Kurikami, H. The relationships among brittleness, deformation behavior, and transport properties in mudstones: An example from the Horonobe Underground Research Laboratory, Japan. J. Geophys. Res. 116, B09206 (2011).

Smyth, R. C. & Sharp, J. M. Jr. The hydrology of tuffs. Geol. S. Am. S. 408, 91–111 (2006).

Brace, W. F. Permeability of crystalline rocks: new in situ measurements. J. Geophys. Res. 89, 4327–4330 (1984).

Schulze-Makuch, D., Carlson, D. A., Cherkauer, D. S. & Malik, P. Scale dependency of hydraulic conductivity in heterogeneous media. Ground Water 37, 904–919 (1999).

Kinoshita, C. & Saffer, D. M. In situ permeability and scale dependence of an active accretionary prism determined from cross-borehole experiments. Geoph. Res. Lett. 45, 6935–6943 (2018).

Lamur et al. The permeability of fractured rocks in pressurised volcanic and geothermal systems. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–9 (2017).

Zoback, M. D. & Hickman, S. In situ study of the physical mechanisms controlling induced seismicity at Monticello Reservoir, South Carolina. J. Geophys. Res. 87, 6959–6974 (1982).

Forster, C. B., Evans, J. P., Tanaka, H., Jeffreys, R. & Nohara, T. Hydrologic properties and structure of the Mozumi Fault, central Japan. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 8010 (2003).

Mitchell, T. M. & Faulkner, D. R. Towards quantifying the matrix permeability of fault damage zones in low porosity rocks. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 339–340, 24–31 (2012).

Marschall, P. & Lunati, I. GAM – Gas Migration Experiments in a Heterogeneous Shear Zone of the Grimsel Test Site. Technical Report 03-11 (NAGRA, Wettingen, Switzerland, 2006).

Scibek, J. Global compilation and analysis of fault zone permeability. (McGill University, Montreal, 2019)

Gomila, R., Arancibia, G., Mitchell, T. M., Cembrano, J. M. & Faulkner, D. R. Palaeopermeability structure within fault-damage zones: A snap-shot from microfracture analyses in a strike-slip system. J. Struct. Geol. 83, 103–120 (2016).

Hashimoto, Y., Nikaizo, A. & Kimura, G. A geochemical estimation of fluid flux and permeability for a fault zone in Mugi melange, the Cretaceous Shimanto Belt, SW Japan. J. Struct. Geol. 31, 208–214 (2009).

Himmelsbach, T., Hotzl, H. & Maloszewski, P. Solute transport processes in a highly permeable fault zone of Lindau fractured rock test site (Germany). Groundwater 36, 792–800 (1998).

Gräsle, W., Kessels, W., Kumpel, H.-J. & Li, X. Hydraulic observations from a one year fluid production test in the 4000 m deep KTB pilot borehole. Geofluids 6, 8–23 (2006).

Pesendorfer, M. & Loew, S. Subsurface exploration and transient pressure testing from a deep tunnel in fractured and karstified limestones (Lotschberg Base Tunnel, Switzerland). Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. 47, 121–137 (2009).

Matsumoto, N. & Shigematsu, N. In-situ permeability of fault zones estimated by hydraulic tests and continuous groundwater-pressure observations. Earth Planets Space 70, 1–12 (2018).

Xue et al. Continuous permeability measurements record healing inside the Wenchuan Earthquake Fault Zone. Science 340(6140), 1555–1559 (2013).

Lu, N., Kwicklis, E. M. & Rousseau, J. P. Determining fault permeability from subsurface barometric pressure. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Sep. 2001, 801–808 (2001).

Illman, W. A. et al. Hydraulic tomography in fractured granite: Mizunami Underground Research site, Japan. Water Resour. Res. 45, W01406 (2009).

Allen, D. M. & Michel, F. A. Evaluation of multi-well test data in a faulted aquifer using linear and radial flow models. Ground Water 36(6), 938–948 (1998).

Sawada, A. et al. Non-sorbing tracer migration experiments in fractured rock at the Kamaishi Mine, Northeast Japan. Eng. Geol. 56, 75–96 (2000).

Baietto et al. Assessment of thermal circulations in strike–slip fault systems: the Terme di Valdieri case (Italian western Alps). Geol. Soc. S. Pub. 299, 317–339 (2008).

Caine, J. S. & Tomusiak, S. R. A. Brittle structures and their role in controlling porosity and permeability in a complex Precambrian crystalline-rock aquifer system in the Colorado Rocky Mountain Front Range. GSA Bull. 115(11), 1410–1424 (2003).

Ganerød, G. V., Braathen, A. & Wilemoes-Wissing, B. Predictive permeability model of extensional faults in crystalline and metamorphic rocks; verification by pre-grouting in two sub-sea tunnels, Norway. J. Struct. Geol. 30, 993–1004 (2008).

Kiguchi, T., Ito, H., Kuwahara, Y. & Miyazaki, T. Estimating the permeability of the Nojima Fault Zone by a hydrophone vertical seismic profiling experiment. Isl. Arc 10, 348–356 (2001).

Shapiro, S. A., Audigane, P. & Royer, J.-J. Large-scale in situ permeability tensor of rocks from induced microseismicity. Geoph. J. Int’l. 137, 207–213 (1999).

Audigane, P., Royer, J. & Kaieda, H. Permeability characterization of the HDR Soultz and Ogachi large-scale reservoir using induced micro-seismicity. Geophisics 67, 204–211 (2002).

Fernandez, M. & Banda, E. Geothermal anomalies in the Valles-Penedes graben master fault: Convection through the horst as a possible mechanism. J. Geophys. Res. 95, 4887–4894 (1990).

David, C., Wong, T.-f, Zhu, W. & Zhang, J. Laboratory measurement of compaction-induced permeability change in porous rock: implications for the generation and maintenance of pore pressure excess in the crust. Pure Appl. Geophys. 143, 425–456 (1994).

Morrow, C. A. & Lockner, D. A. Permeability differences between surface-derived and deep drillhole core samples. Geophys. Res. Lett. 21(19), 2151–2154 (1994).

Zoback, M. D. Reservoir Geomechanics. (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Vidal, J. & Genter, A. Overview of naturally permeable fractured reservoirs in the central and southern Upper Rhine Graben: Insights from geothermal wells. Geothermics 74, 57–73 (2018).

Vidal, J., Genter, A. & Schmittbuhl, J. How do permeable fractures in the Triassic sediments of Northern Alsace characterize the top of hydrothermal convective cells? Evidence from Soultz geothermal boreholes (France). Geoth. Energy 3(8), 1–28 (2015).

Sausse, J., Dezayes, C., Genter, A. & Bisset, A. Characterization of fracture connectivity and fluid flow pathways derived from geological interpretation and 3D modelling of the deep seated EGS reservoir of soultz (France). In: Proceedings, Thirty-Third Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering Stanford University, Stanford, California, January 28–30, SGP-TR-185 (Stanford University, California, 2008).

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Tom Gleeson (U.Victoria) and Jeff McKenzie (McGill U.) for guidance and support on this long project. The funding was provided by FQRNT in Quebec, Canada, and partly by the IAH Scholarship 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S. designed the methodology, reviewed the world-wide studies, compiled and entered the data, and wrote journal article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Online-only Tables

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ applies to the metadata files associated with this article.

About this article

Cite this article

Scibek, J. Multidisciplinary database of permeability of fault zones and surrounding protolith rocks at world-wide sites. Sci Data 7, 95 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-0435-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-0435-5

This article is cited by

-

Constraints on upper crustal fluid circulation and seismogenesis from in-situ outcrop quantification of complex fault zone permeability

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Radionuclide Migration From an Underground Radioactive Waste Repository Under the Influence of Tectonic Fault Emergence: the Nizhnekanskiy Massif (Siberia, Russia) Example

Environmental Modeling & Assessment (2023)

-

Radon transport carried by geogas: prediction model

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Assessment of deep geothermal research and development in the Upper Rhine Graben

Geothermal Energy (2022)

-

Influence of tectonic perturbations on the migration of long-lived radionuclides from an underground repository of radioactive waste

Environmental Earth Sciences (2022)