Abstract

Tidal and wind-driven near-inertial currents play a vital role in the changing Arctic climate and the marine ecosystems. We compiled 429 available moored current observations taken over the last two decades throughout the Arctic to assemble a pan-Arctic atlas of tidal band currents. The atlas contains different tidal current products designed for the analysis of tidal parameters from monthly to inter-annual time scales. On shorter time scales, wind-driven inertial currents cannot be analytically separated from semidiurnal tidal constituents. Thus, we include 10–30 h band-pass filtered currents, which include all semidiurnal and diurnal tidal constituents as well as wind-driven inertial currents for the analysis of high-frequency variability of ocean dynamics. This allows for a wide range of possible uses, including local case studies of baroclinic tidal currents, assessment of long-term trends in tidal band kinetic energy and Arctic-wide validation of ocean circulation models. This atlas may also be a valuable tool for resource management and industrial applications such as fisheries, navigation and offshore construction.

Measurement(s) | ocean current |

Technology Type(s) | Gauge or Meter Device • digital curation |

Factor Type(s) | time • current • geographic location • tidal current |

Sample Characteristic - Environment | ocean |

Sample Characteristic - Location | Arctic Ocean region |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12581435

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Tidal currents are often the dominant source of current variability and play an important role in shaping the Arctic Ocean hydrography and sea ice cover1,2,3. Tidal currents are also a key element shaping the marine ecosystem with impacts ranging from creating the habitat of the intertidal zone to mixing of nutrients. Furthermore, information about tidal currents is used for many practical applications, such as navigation, fisheries and marine structures and operations.

Barotropic tidal models1,4 based on the depth-integrated momentum and continuity equations provide ocean surface height and depth-averaged currents for major tidal constituents throughout the Arctic. These comparatively simple models show very little tidal activity (<0.5 cm/s) in the central Arctic deep basins, but strong amplitudes (>10 cm/s) over portions of the continental shelves and slopes.

Where barotropic tidal currents flow across steep slopes or rough topography in the presence of stratification, energy can be converted from barotropic to baroclinic (internal) tides whose energy finally dissipates in mixing processes5. The importance of baroclinic tidal processes was highlighted, for example, by Luneva et al.3, who found that the addition of tidal currents to an atmospherically forced three-dimensional simulation reduced pan-Arctic sea ice volume by ~15%. The authors attributed this sea ice reduction to the entrainment of warm subsurface Atlantic Water into the cold near-surface waters by mixing caused by increased surface stresses and by upper-ocean shear instabilities from the combination of baroclinic tides and the atmospherically forced three-dimensional circulation. In contrast to barotropic tides, the generation, propagation and dissipation of baroclinic tidal waves are sensitive to stratification, mean flow, and energy losses through friction and mixing within the water column. They may, therefore, change substantially with variations in the background ocean state associated with weather-band and seasonal changes in forcing, ocean mesoscale variability (e.g., eddies) and as the Arctic Ocean changes on longer time scales e.g.6.

Despite the importance of tides for the Arctic Ocean and its sea ice, most ocean general circulation models used for climate projections do not currently include tides. At this time, comprehensive Arctic oceanographic data sets are limited to hydrographic variables (salinity, temperature and density, e.g. The Arctic Ocean Atlas, compiled by the US-Russian Environmental Working Group with data spanning the 1950s to the 1980s7) with no direct information about ocean currents. With the increased deployment of moored Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers in the Arctic in the last two decades, high-resolution current observations (predominantly of the upper ocean) have become available. Using these data, detailed analyses of tidal current dynamics have been carried out at several specific locations in the Arctic such as the Beaufort Sea shelf8, the Yermak Plateau9, the Nares Strait10, the Laptev Sea11 and the eastern Eurasian Basin12,13). These studies emphasize the importance of tidal currents to local ocean dynamics. However, a pan-Arctic perspective on observed 3-D tidal currents is required, both to synthesize and expand our understanding of tidal dynamics and its interactions with hydrography and sea ice, and to validate numerical models. Here we present an atlas of tidal currents from available moored current meter records spanning the past two decades in all sectors of the Arctic Ocean. The aim is to provide a data set enabling regional in-depth analyses of time-depth dependent tidal currents. With information about local baroclinicity, this atlas complements existing altimetry-based products of barotropic tides and provides reference points for evaluating and constraining model simulations. Long time series may be used to identify and analyse trends of tidal-band current dynamics.

Methods

Data acquisition and pre-processing

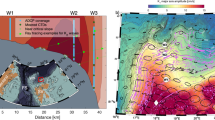

One of the targets for this atlas was to collect all available Arctic current profile records of at least 1-year length and 1-h resolution to resolve tidal oscillations. With the help of many colleagues, we gathered 429 records from all sectors of the Arctic (although not homogeneously distributed), spanning the last two decades (Online-only Table 1, Fig. 1).

Spatial and temporal distribution of current velocity records contained in the atlas. Top: Map showing locations of the records (coloured dots). Colours indicate grouping utilized for visualizations. Black circles show the centroid location and number of each cluster. Bottom: Histogram of record distribution over time.

Most observations were obtained with Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers (ADCPs) from TELEDYNE RD Instruments (TRDI), with the 300 kHz variant being the most commonly used. ADCPs generally provide vertical profiles of horizontal velocity with a vertical resolution and range depending on the instrument’s frequency and set-up. In the Arctic, where there are relatively few backscattering particles outside the shallow shelf regions, typical vertical resolutions range from 0.5 to 5 m with vertical ranges spanning 15 m to ~300 m for 1200 kHz and 75 kHz ADCPs, respectively. Typical temporal resolution of the records is 1 h, although some deployments have resolution of 15–30 minutes. While vertical resolution and range vary substantially between models of different frequencies, the expected accuracies for speeds and directions are generally similar and are given as ±0.5 cm/s and ±2° for vertical averaging bin sizes of 2 m for the 300 kHz ADCPs. Known issues with moored ADCP records are discussed in the section “Technical Validation”. In the Barents Sea Opening region, where ADCP records were sparse, we complemented the atlas with data from Recording Current Meters (RCMs), which work in an analogous fashion to mechanical anemometers and provide point observations of currents at the depth they are moored. Aanderaa RCM7 instruments have a starting velocity of 2 cm/s with expected accuracies of 1 cm/s or 4% of the actual speed (whichever is higher) and the accuracy for the direction is expected to be 5° (Aanderaa Instruments data sheet). While the current speed measured by RCMs is averaged over several observations within a chosen time interval (usually 1 h) around the designated time of measurement, the compass direction is retrieved only once, instantaneously at the designated time.

The data used in this atlas came from many different sources in many different formats. The number of steps required to arrange the data in a common format depended on the original format and state of processing. Generally, the first step was to ensure a uniform grid of time and depth. It was not uncommon for the records to have a drifting clock or otherwise inconsistent time spacing. If the original time vector was not equally spaced throughout the length of the deployment, the data were interpolated onto a synthetic time vector with 1 h time interval. Data gaps of more than 1 h were kept but filled with missing data delimiter “NaN”. If information about time-varying instrument depth was available, either from the pressure sensor of the ADCP itself or Conductivity, Temperature, Depth (CTD) sensors on the same mooring near the ADCP’s depth, the depth of each ADCP bin was adjusted at every time step. The data were then interpolated onto a uniform pressure vector (spreading the whole depth range covered by observations while maintaining the original increment) at each time step. If no pressure record was available, a constant instrument depth at the depth of deployment was used, and all bin depths were assumed to be constant over time. Since some depth information was provided in pressure units (dbar) and others in distance from the surface (meters) without necessarily providing CTD data for conversion, we decided to treat any depth information as pressure. The error associated with this approximation is ~1.1% of the depth of the sensor. Since most records only cover the upper ocean (<100 m depth), the error is small and tends to be less than 1 m. We chose cm/s as common unit for all velocities (and tidal amplitudes) presented in the atlas. This is common practice in the field and allows for the most efficient and readable notation as almost all tidal band currents throughout the Arctic are of order O(1–10) cm/s.

A unique filename was created for each record consisting of region, mooring name, instrument type and deployment years (e.g. lapt_1893_ADCP300_2013-14).

Tidal analysis

We analysed the current velocities using the T_TIDE Matlab toolbox14, which is based on tidal analysis methods described by Foreman15. T_TIDE performs a harmonic analysis based on the known frequencies for up to 69 tidal constituents and calculates all relevant tidal ellipse parameters (major and minor axis amplitudes, orientation, sense of rotation direction and phase) with their confidence intervals.

The number of resolvable constituents is determined by the length of the time series. In most ocean environments, the bulk of the total tidal variance is in eight constituents, four semidiurnal (M2, S2, K2, N2) and four diurnal (O1, K1, P1, Q1). Tidal analysis on shorter windows (<~180 days, as commonly available from temporary tide gauge deployments), report the combination of S2 and K2 as S2 only, while K1 and P1 are reported as K1. For barotropic tide heights, where amplitudes and phases are stable in time, these pairs can be separated in short records by “inference”14,15. In the present analysis, however, we expect that much of the tidal energy is in time-varying baroclinic modes where the assumptions required for inference may not apply.

The tidal parameters presented in this atlas are based on tidal analysis at each depth level over three different time periods: 30-day sliding windows (with original time increment), 90-day sliding windows (with 5-day increment) and the full record. Tidal parameters are reported for the midpoint of each window, rendering the temporal span of tidal parameters at each end 15 or 45 days shorter than the original time series for the 30- and 90-day analyses, respectively. T_TIDE is capable of dealing with some missing data at the cost of broadening confidence intervals. In practice, we chose to carry out tidal analysis only if less than 1/3 of the data within the window were missing to avoid large uncertainties.

The rationale for these three different approaches is as follows:

-

30-day sliding windows run over the whole record at each depth level. This method is used to identify short-term (monthly) variability of baroclinic tidal currents. A major caveat of this analysis is the potential effect of wind-driven inertial currents that may influence and even dominate tidal analysis in the upper ocean (see “Technical Validation”). Because of the unknown but potentially substantial influence of inertial currents on individual constituents, the user should not interpret upper ocean variability in this product as evidence of changing baroclinic tides (see technical validation below).

-

90-day analysis yields tidal parameters averaged over a longer period of time that reduces the influence of short-term synoptic wind influences as well as short-term changes of true baroclinic tidal currents on the harmonic analysis. This product is designed to allow for detailed analysis of individual tidal constituent ellipses and their variability over depth and time on seasonal to inter-annual time scales.

-

Full-record analysis is carried out using all resolvable constituents and yields a single set of ellipse parameters for each. This provides robust, time-mean tidal information largely independent of short-term influences and thus represents barotropic and phase-locked baroclinic tides16. Note that the outcome of this analysis is not equivalent to averaging any of the previously discussed shorter-window analyses over the full record. Although differences in major axis amplitudes are often relatively small, other ellipse parameters (such as phase and orientation) may differ substantially. Additionally, full-record analysis is used to produce a “tidal prediction”; i.e., currents due to the combination of all T_TIDE-derived tidal constituents for the whole record at the original time increment (i.e. hourly in most cases).

-

Supplementing harmonic tidal analysis, tidal band currents (TBC) are defined as currents that are band-pass filtered for periods between 10 h and 30 h. This comprises all semi-diurnal and diurnal tidal constituents as well as wind-driven inertial currents. This method does not require any averaging or smoothing over time and thus provides original amplitudes and variability for currents within the tidal band.

Data Records

The atlas is archived as a collection of netCDF files, one for each instrumental record. Each file contains comprehensive metadata and a number of tidal variables as listed and shortly described in Table 1. The pathway to accessing the atlas is via the “table of inventory”, a human- and machine-readable table that provides relevant meta-information (file name, mooring name, region, start and end date, position, estimated bottom depth, instrument type, depth range covered and institution of origin), so that users can efficiently identify the records suitable for their needs. The data are accessible on the National Science Foundation Arctic Data Center (https://doi.org/10.18739/A26M3340D17).

Technical Validation

Instrument-related quality assessment

ADCP measurements close to the surface inherently suffer from contaminations due to surface reflections of sidelobe energy. This error is proportional to the cosine of the beam angle and the distance of the instrument to the surface and amounts to ~6% of the range for a typical 20° beam angle18. The effective range of contamination may be somewhat greater depending on the bin sizes. Since, for many records complete instrument information was unavailable, we chose to provide a mask blanking out the top 10% of the range of any records that reach the surface.

ADCP measurements depend on particles drifting in the water column that reflect the ADCP’s transmitted acoustic signal back to the instrument, where the Doppler shift of the signal is used to calculate velocities. However, in the relatively quiescent Arctic, the concentration of suspended particles can be very low, especially during winter when biological primary production effectively halts. With weak echoes, the ranges of ADCP profiles are substantially reduced: e.g. the nominal range for 300 kHz ADCPs exceeds 150 m but, in the Arctic, their effective range is ~50–60 m. Low backscatter amplitudes also lead to greater errors for speed and direction. Most records compiled in this atlas do not provide the extensive metadata to investigate this issue consistently, but erroneous data is commonly discarded in standard processing procedures.

Influence of wind-driven inertial currents on tidal analysis

In this section, we motivate the use of different window-lengths within T_TIDE tidal analysis to partially mitigate the impact of wind-driven inertial currents on the analysis. Wind-driven inertial currents may substantially impact T_TIDE harmonic analysis in the Arctic13, where the local inertial period (12.735–11.967 h between 70° and 90° N) is very close to periods of the two major semidiurnal tidal constituents M2 (~12.421 h) and S2 (12.000 h). Baumann et al.13 demonstrated the impact of wind-driven inertial currents on tidal analysis using a damped-slab model19,20 with two different idealized mixed layer depths (10 m and 50 m). Effects are greatest for the 10-m SML case, which is representative of ice-free summers when surface mixed-layer depths are shallow. For the deeper 50-m case, the influence of wind-driven inertial currents is much reduced.

Here we use the same damped-slab model, for wind and ice conditions from model reanalysis products at a location offshore of the Laptev Sea continental slope, to demonstrate the different effects on 30-day, 90-day and full-time tidal analysis. After removing data recorded within 10% of the ocean surface from the ADCP depth, only 6% of the valid data are located within the top 10 m, whereas 54% lie between 10 and 50 m. We therefore consider the 50-m SML case of the slab model as the more representative condition for wind-forced inertial signals in the atlas.

To demonstrate the influence of inertial noise on T_TIDE tidal analysis, we use an idealized tidal signal consisting of a complex harmonic oscillation at M2 frequency, whose amplitude (on average 8 cm/s) undergoes a seasonal variation (3 cm/s amplitude), similar to observed tides in the Laptev Sea and upper eastern Eurasian continental slope region (not shown). To this signal we added the simulated inertial currents from the slab model. We show the output of T_TIDE tidal analysis in Fig. 2. The 30-day analysis exhibits prominent high-frequency variability, which in this case is noise stemming from the inertial currents. As a consequence, the full range of M2 major axis amplitudes, a simple measure of variability over time, amounts to 8.2 cm/s which constitutes an overestimation of 37% compared to the expected seasonal variability of 6 cm/s. The 90-day analysis provides a clear seasonal cycle with major axis amplitudes exhibiting a range of 6.4 cm/s (i.e. 8% overestimation) and the full-records analysis provides amplitudes matching those of the input, despite variability through seasonality and wind-driven inertial currents. We note that, in conditions where inertial currents are continuously strong (more than half of tidal amplitude), inertial impacts are high on the 90-day and even full-record analysis as well. Although the dynamics are not well understood, we expect these conditions to be most significant close to the surface (within ~30 m) during ice-free summers.

Tidal analysis using different window lengths performed on an artificial time series. The time series is constructed to resemble realistic conditions found at the eastern Eurasian continental slope (see Baumann et al.13) and consists of a complex harmonic oscillation at M2 frequency with an amplitude of 8 cm/s. The amplitude undergoes a seasonal cycle represented by a cosine function with 365.25-day period and amplitude of 3 cm/s. To this, we added inertial oscillations (average amplitude ~2 cm/s) simulated from a slab-model with 50-m SML (see13 for details). The 30-day and 90-day analyses predominantly follow the seasonal cycle, but noise has a substantial impact on the 30-day analysis. Some minor distortions of the seasonal signal are also visible for the 90-day analysis. The full-record analysis produces a single set of tidal ellipse parameters with the major axis amplitude almost exactly matching the input.

Influence of low frequency variability on tidal analysis

In the full record analysis, low frequency tidal constituents such as seasonal (SA) and semi-seasonal (SSA) are included depending of the length of the record. We cannot determine whether the energy ascribed to these constituents by T_TIDE harmonic fits is actually of tidal origin or merely follows seasonal variability caused by other physical drivers (analogous to the impact of inertial oscillations on semidiurnal constituents).

Usage Notes

The wide range of possible applications (including climate modelling, fisheries, and offshore construction) requires high flexibility of the atlas. Using the “table of inventory” described in “Data Records”, users can easily identify the records useful to their specific task.

Large scale or pan-Arctic applications may benefit from a grouping of a number of (or all) records using clustering algorithms. Due to the strong dependence of tidal currents on topography, we recommend that clustering takes into account water depth as well as geographical location. An example of location and depth dependent clustering of all records is presented in Fig. 1. In the following section we use this clustering to illustrate pan-Arctic tidal current properties.

Choosing the right atlas product

Full-record analysis. Comparison with barotropic tidal models

Barotropic tidal models are comparatively simple models that predict total tidal currents and current ellipse parameters for individual constituents from gravitational tidal forcing4. Despite their simplicity, results from these models are widely used in scientific research and many practical applications. The vertically averaged results of full-record tidal analyses from each ADCP record are the closest approximation to barotropic tidal currents in the atlas. Using the clustering shown in Fig. 1, the pan-Arctic spatial variability of major axis amplitudes from depth-averaged currents for the six most energetic diurnal and semidiurnal constituents shows that tidal current amplitudes and the relative contribution of the individual constituents vary widely across the Arctic (Fig. 3 top). Strongest tidal currents are observed in the Nares Strait (cluster #5) and Davis Strait (cluster #6), with M2 major axis amplitudes exceeding 20 cm/s followed by the diurnal K1 constituent with ~12 cm/s. Other regions of substantial tidal activity include the Barents Sea Opening (cluster #8) with ~12 cm/s for the leading M2 tide and very small diurnal contributions, the western Eurasian Basin continental slope (cluster #9) and the Laptev Sea (cluster #11) with dominating M2 amplitudes of 6–8 cm/s. While the Yermak Plateau is known for strong diurnal tidal currents9, in this visualization it is clustered together with Fram Strait moorings where the tidal signal is much weaker, yielding an average of only ~4 cm/s. Throughout deep basins (clusters #10, #12, #13 and #3) and the Pacific sector shelves and continental slopes (clusters #1, #2 and #4), tidal amplitudes for individual constituents are weaker (<4 cm/s) than those on the continental slopes on the Atlantic side.

Major axis amplitudes of tidal constituents (Umaj) from full-record analysis and their comparison to a barotropic tidal model. (top) Amplitudes are averaged vertically and over all records within each cluster. (bottom) Difference of Umaj for tidal constituents from full-record analysis and barotropic model output. Model data stems from Padman and Erofeeva4.

These data may be used to validate barotropic tidal models. For example, differences between this atlas and output from the inverse barotropic tide model from Padman and Erofeeva4 (taken at the locations of every record in the atlas and performing the same averaging within each cluster) are relatively small (<2 cm/s, Fig. 3) with no systematic bias, and thus confirm the overall performance of that model.

30-day and 90-day analyses: Spatio-temporal structure and variability of tidal parameters

While barotropic tidal models provide general tidal information, which is invariant over depth and time, our new atlas provides information on the depth-dependence and temporal variability of tidal currents. The 30-day and 90-day analyses resolve the variability for individual tidal constituents on timescales from months to years, depending on the length of the record, including the seasonal cycle. Averaged over all records, the range of variability of M2 major axis amplitudes at 50 m depth amounts to 110% and 70% of the local mean (barotropic) major axis amplitude for the 30-day and 90-day analysis, respectively (or 4.8 cm/s and 2.8 cm/s in absolute terms) (Fig. 4). Even in regions with low average tidal amplitude (clusters #1–4), temporal variability of M2 tidal amplitudes can exceed 5 cm/s. Note that wind-driven inertial influence cannot be categorically excluded at 50 m depth. Smallest variability is found in cluster #10, centered at the North Pole, where tidal currents never exceed 2 cm/s (Fig. 4). Within the deep Beaufort Sea (cluster #3), records show a greater variability, sometimes exceeding 4 cm/s for the 30-day analysis. Generally, temporal variability of tidal currents is stronger in areas where tidal currents are strong, but the range of variations is smaller relative to the mean amplitude of tidal currents. For example, the average range of major axis amplitudes from 30-day analyses in cluster #5 is 9.3 cm/s, which is 40% of the mean amplitude (23 cm/s), whereas for cluster #10 an average range of 2.8 cm/s corresponds to 250% of the mean amplitude (1.1 cm/s, Fig. 4). A standout region for high variability of relatively strong tidal currents is cluster #11, comprising the Laptev Sea and the eastern Eurasian Basin continental slope and was extensively discussed in Baumann et al.13. Figure 4 further demonstrates that the difference between records within a cluster in most cases exceeds temporal variability within a record, highlighting the great spatial variability of tidal currents.

Spatio-temporal variability of tidal currents, illustrated by the range of M2 Umaj (from 30-day (light shading) and 90-day (solid colour) analysis, at 50 m depth) for each record in each cluster. The records within each cluster are sorted by average Umaj (black dots). For readability, horizontal plotting space was stretched for clusters with a smaller number of records (clusters #5 and #7-#13).

The vertical structure (and thus shear) of baroclinic tidal currents is of major interest for the investigation of oceanic mixing processes. Tidal mixing can be important regionally9,21 and directly affects the sea ice cover in model simulations e.g.3. The vertical structure of M2 major axis amplitudes varies regionally across the Arctic (Fig. 5). While cluster-average profiles cannot be used to identify mixing processes, they may indicate the regional tendency for baroclinicity. While some regions exhibit vertical profiles with little vertical structure (clusters #4, #7, #8, #10 and #13), others show clear vertical gradients with surface amplification (clusters #1, #2, #3 and #12) or other structures (clusters #5, #6 and #11).

Cluster-average profiles of M2 major axis amplitudes from 90-day analysis over the top 100 m. Averages were taken over 10 m bins with squares in the profiles showing the center of the bins and the sizes reflect the relative number of measurements in that bin. Shading denotes ±1 standard deviation. The (linear) x-axis scales are different in each plot, but the vertical grid lines are always spaced by 2 cm/s.

Tidal band currents and tidal prediction: High-frequency variability and kinetic energy

Tidal band currents (TBCs) provide the full spectrum of amplitudes and variability exerted by the combination of wind-driven inertial and tidal currents at diurnal and semidiurnal frequencies. Presently, there is no way to separate the wind-forced and tidal components analytically, so their properties have to be assessed jointly. The importance of TBCs relative to the full spectrum of observed raw currents across the Arctic can be seen in Fig. 6 (top and right). Despite regionally strong total currents in the Pacific sector of the Arctic (>50 cm/s at clusters #1, #2 and #3), TBCs are small throughout the region, barely reaching 10 cm/s. In the Atlantic sector, amplitudes of TBCs are often comparable to original, measured, (“raw”) current amplitudes (clusters #5, #6, #8 and #11), indicating that diurnal and semidiurnal tidal currents together with inertial currents are the defining characteristics of the dynamics in these regions. Figure 6 further reveals that TBCs can have a directional structure that fundamentally differs from the original raw currents (clusters #4, #7 and #9), likely caused by the interaction between tides and topographic features.

Regional current roses for observed raw currents (top), tidal band currents (TBC, right) and tidal prediction from full-record analysis (bottom). The roses are aligned with the true north of their respective centroid location (i.e. they fit in the map as they are without further rotation) and contain all observations within each cluster. The length of each 10° bin is proportional to the percentage of data within this bin. A nonlinear colour scale marks speed.

T_TIDE tidal current predictions based on full-record analysis include all tidal constituents that satisfy the Rayleigh criterion (i.e. that can be resolved given the length of the record)15. The prediction allows for the evaluation of amplitude and variability of current strength (or kinetic energy) ascribed to mean tidal currents by T_TIDE tidal analysis at any point in time of the record. Figure 6 shows that in regions where diurnal and semidiurnal tides are known to be strong, the tidal prediction is very similar to TBCs (compare clusters #5–9 in Fig. 6 bottom and right). In some regions, where tidal currents are known to be relatively weak, tidal prediction yields surprisingly strong currents (cluster #1, #2 and #4). This is due to the inclusion of low-frequency tidal constituents (e.g. seasonal (SA), semi-seasonal (SSA), monthly (Mm) and fortnightly (Mf)), which may coincide with other natural low-frequency drivers, such as the seasonal cycle of sea ice. Consequently, the absolute values should be treated with caution and the primary use may be the validation of equally processed output from numeric models.

Concluding remarks

Tidal currents play a vital role in the Arctic climate and ecosystems, but our understanding of their spatio-temporal variability is limited. The goal of our atlas of tidal currents described herein is to provide a tool that enables investigations into regional high-frequency dynamics in a changing Arctic Ocean. As a ground-truth for the modelling community, this may contribute to more reliable projections of future Arctic Ocean states. In order to maximize utility, we have provided different tidal products for different applications:

-

Tidal harmonic parameters based on full-record analyses, e.g. for validation of barotropic tidal models.

-

90-day tidal analyses, e.g. for the analysis of seasonal to interannual variability of tidal currents.

-

30-day tidal analyses, e.g. for intra-annual variability. Users should be aware of the potentially dominating effect of wind-driven inertial currents on tidal parameters in this product.

-

Tidal band currents (TBCs, band-pass filtered over 10–30 h), e.g. for analysis of high frequency variability without distinguishing between wind-driven inertial oscillations and tides.

-

Tidal prediction for amplitude and variability of tidal currents as provided by T_TIDE tidal analysis.

References

Kowalik, Z. & Proshutinsky, A. Y. The Arctic Ocean Tides. The Polar Oceans and Their Role in Shaping the Global Environment 1, 137–158 (American Geophysical Union (AGU), 1994).

Proshutinsky, A. et al. Sea level variability in the Arctic Ocean from AOMIP models. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 112, 129 (2007).

Luneva, M. V., Aksenov, Y., Harle, J. D. & Holt, J. T. The effects of tides on the water mass mixing and sea ice in the Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 120, 6669–6699 (2015).

Padman, L. & Erofeeva, S. A barotropic inverse tidal model for the Arctic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, 53–4 (2004).

Simmons, H. L., Hallberg, R. W. & Arbic, B. K. Internal wave generation in a global baroclinic tide model. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 51, 3043–3068 (2004).

Carmack, E. et al. Toward Quantifying the Increasing Role of Oceanic Heat in Sea Ice Loss in the New Arctic. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc 96, 2079–2105 (2015).

Environmental Working Group. Joint U.S.-Russian Atlas of the Arctic Ocean. NSIDC https://doi.org/10.7265/N5H12ZX4 (1997).

Kulikov, E. A. Barotropic and baroclinic tidal currents on the Mackenzie shelf break in the southeastern Beaufort Sea. J. Geophys. Res. 109, 307–18 (2004).

Fer, I., Müller, M. & Peterson, A. K. Tidal forcing, energetics, and mixing near the Yermak Plateau. 1812-0792 11, 287–304 (2015).

Münchow, A. & Melling, H. Ocean current observations from Nares Strait to the west of Greenland: Interannual to tidal variability and forcing. J. Mar. Res. 66, 801–833 (2008).

Janout, M. A. & Lenn, Y.-D. Semidiurnal Tides on the Laptev Sea Shelf with Implications for Shear and Vertical Mixing. J. Phys. Oceanogr 44, 202–219 (2014).

Pnyushkov, A. V. & Polyakov, I. V. Observations of Tidally Induced Currents over the Continental Slope of the Laptev Sea, Arctic Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr 42, 78–94 (2012).

Baumann, T. M. et al. Semidiurnal current dynamics in the Arctic Ocean’s eastern Eurasian Basin. Preprint at ESSOAr, https://doi.org/10.1002/essoar.10502530.1 (2020).

Pawlowicz, R., Beardsley, B. & Lentz, S. Classical tidal harmonic analysis including error estimates in MATLAB using T_TIDE. Computers & Geosciences 28, 929–937 (2002).

Foreman, M. Manual for tidal currents analysis and prediction. (Institute of Ocean Sciences, Patricia Bay, Sidney, BC, 1978).

Ray, R. D. & Mitchum, G. T. Surface manifestation of internal tides in the deep ocean: observations from altimetry and island gauges. Progress in Oceanography 40, 135–162 (1997).

Baumann, T. M. et al. Arctic Tidal Current Atlas from Moored Current Observations, Arctic Ocean, 1998–2018. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.18739/A26M3340D (2019).

RD Instruments. WorkHorse Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler Technical Manual. P/N 957-6150-00 (2005).

Pollard, R. T. & Millard, R. C. Comparison between observed and simulated wind-generated inertial oscillations. Deep Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts 17, 813–821 (1970).

D’Asaro, E. A. The Energy Flux from the Wind to Near-Inertial Motions in the Surface Mixed Layer. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 15, 1043–1059 (1985).

Holloway, G. & Proshutinsky, A. Role of tides in Arctic ocean/ice climate. J. Geophys. Res. 112, 3069–10 (2007).

Sundfjord, A., Renner, A. H. & Beszczynska-Möller, A. A-TWAIN mooring hydrography and current data Sep 2012 - Sep 2013. Norwegian Polar Institute, https://doi.org/10.21334/npolar.2017.73d0ea3a (2017).

Mudge, T., Weingartner, T. & Dobbins, E. Eastward and northward components of ocean current, temperature, salinity and ice analysis collected from industry sponsored moorings in the Chukchi Sea, Alaska from 2008-09-08 to 2016-10-13. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, https://accession.nodc.noaa.gov/0164964 (2017).

McRaven, L. Mooring Observations from the Atlantic Water Inflow Experiment (ATWAIN) from September 21, 2012 through September 19, 2013. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.18739/A2S569 (2018).

Gratton, Y. et al. Long-term oceanic observatories (moorings) in the Beaufort Sea during the Canadian Arctic Shelf Exchange Study, 2002-2004. Polardata.ca, https://doi.org/10.5884/11653 (2015).

Weingartner, T., Statscewich, H., Stoudt, C. & Dobbins, E. Currents, Temperature, Salinity, and Sea Ice measurements from moorings in Barrow Canyon, Chukchi Sea, 2010–2015. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, https://accession.nodc.noaa.gov/0160090 (2017).

Okkonen, S. Mooring data 2010-2011, south flank of Barrow Canyon. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.18739/A20K5X (2012).

Okkonen, S. Mooring data 2011-2012, south flank of Barrow Canyon. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.18739/A21C7X (2012).

Lee, C. M. Moored ADCP current profiles from the Davis Strait observational array. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.18739/A2TV7W (2009).

Stabeno, P. J. et al. NOAA/EcoFOCI Chukchi Sea ADCP Mooring time-series data, stations C1, C2, and C3, 2010-08-29 to 2012-08-22, including zonal (U) and meridional (V) current measurements. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, https://accession.nodc.noaa.gov/0149848 (2016).

Fukamachi, Y. et al. SIZOnet: Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP) data, Barrow, AK, USA. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.18739/A2MT1D (2016).

de Steur, L. Moored current meter data from the western Fram Strait 1997-2009. Norwegian Polar Institute, https://doi.org/10.21334/npolar.2019.8bb85388 (2019).

Simmons, H. Beaufort Sea Mooring I1. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.18739/A25S6X (2013).

Simmons, H. Beaufort Sea Mooring I2. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.18739/A2X911 (2013).

Simmons, H. & Martini, K. I. Beaufort Sea Mooring I3. Arctic Data Center https://doi.org/10.18739/A2233Z (2013).

Woodgate, R. A. Increases in the Pacific inflow to the Arctic from 1990 to 2015, and insights into seasonal trends and driving mechanisms from year-round Bering Strait mooring data. Progress in Oceanography 160, 124–154 (2018).

Woodgate, R. A., Stafford, K. M. & Prahl, F. A synthesis of year-round interdisciplinary mooring measurements in the Bering Strait (1990–2014) and the RUSALCA years (2004–2011). Oceanography https://doi.org/10.2307/24861901 (2015).

Muenchow, A. Canadian Archipelago Throughflow Study: ADCP moorings 2003-06. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.18739/A23K67 (2013).

Muenchow, A. Canadian Archipelago Throughflow Study: ADCP moorings 2007-09. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.18739/A2RR77 (2014).

Weingartner, T. UAF Barrow Canyon and Central Channel Moorings. Version 1.0. Earth Observing Laboratory Data, https://doi.org/10.5065/D62805QS (2010).

Weingartner, T. J. et al. Circulation and water properties in the landfast ice zone of the Alaskan Beaufort Sea. Continental Shelf Research 148, 185–198 (2017).

Weingartner, T., Danielson, S., Kasper, J. L. & Okkonen, S. R. Circulation and water property variations in the nearshore Alaskan Beaufort Sea (1999–2007). OCS Study MMS (2009).

Polyakov, I. V. NABOS II - ADCP Water Current Data 2013 - 2015. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.18739/A2RS9B (2016).

Polyakov, I. V. Acoustic Dopper Current Profiler (ADCP) from moorings taken in the Eurasian and Makarov basins, Arctic Ocean, 2015-2018. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.18739/A2HT2GB80 (2019).

Fer, I. & Peterson, A. K. Moored measurements of ocean current, temperature and salinity from Yermak Plateau, Sep. 2014–Aug. 2015. Norwegian Marine Data Centre, https://doi.org/10.21335/NMDC-1508183213 (2019).

von Appen, W.-J., ller, A. B.-M. & Fahrbach, E. Physical oceanography and current meter data from mooring F3-15. PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.853902 (2015).

von Appen, W.-J., ller, A. B.-M. & Fahrbach, E. Physical oceanography and current meter data from mooring F4-15. PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.853903 (2015).

von Appen, W.-J., ller, A. B.-M. & Fahrbach, E. Physical oceanography and current meter data from mooring F5-15. PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.853904 (2015).

von Appen, W.-J., ller, A. B.-M. & Fahrbach, E. Physical oceanography and current meter data from mooring F7-12. PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.853905 (2015).

von Appen, W.-J., ller, A. B.-M. & Fahrbach, E. Physical oceanography and current meter data from mooring F8-13. PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.853907 (2015).

von Appen, W.-J., ller, A. B.-M. & Fahrbach, E. Physical oceanography and current meter data from mooring F10-12. PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.853910 (2015).

von Appen, W.-J., ller, A. B.-M. & Fahrbach, E. Physical oceanography and current meter data from mooring F15-9. PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.853918 (2015).

von Appen, W.-J., ller, A. B.-M. & Fahrbach, E. Physical oceanography and current meter data from mooring F16-9. PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.853920 (2015).

Janout, M., lemann, J. A. H., Timokhov, L. & Kassens, H. Moored measurements of current, temperature and salinity on the Laptev Sea shelf in 2013-2014. PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.908837 (2019).

Morison, J. H. et al. North Pole Environmental Observatory (NPEO) Oceanographic Mooring Data. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.5065/D6P84921 (2009).

Pickart, R. S., Fratantoni, P. S. & Torres, D. J. Moored ADCP Observations 2002-2003 from the Beaufort Shelf Edge Mooring Array. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.5065/D6J964FR (2009).

Pickart, R. S., Fratantoni, P. S. & Torres, D. J. Moored ADCP Observations 2003–2004 from the Beaufort Shelf Edge Mooring Array. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.5065/D6FF3QF3 (2009).

Aagaard, K. D. & Woodgate, R. UW Mooring Data for the Northern Chukchi Sea 2002-2004. Arctic Data Center, https://doi.org/10.5065/D64747X3 (2007).

Fer, I. Current measurements at the Storfjord sill, Svalbard, Sept. 2003–May 2007. Norwegian Marine Data Centre, https://doi.org/10.21335/NMDC-273201156 (2019).

Gascard J-C. et al. ADCP mooring data in 2007-2008 north of Svalbard over the Yermak Plateau in the Yermak Pass. Polardata.ca https://doi.org/10.17882/51023 (2017).

ArcticNet/Amundsen Science Mooring Data Collection. Mooring data of the Integrated Beaufort Observatory (iBO), a project from the Beaufort Regional Environmental Assessment (BREA) Marine Observatories in the Canadian Arctic. ArcticNet Inc. and Amundsen Science, Québec, Canada. Polardata.ca https://doi.org/10.21335/NMDC-273201156 (2019).

Fortier, M. et al. Beaufort Regional Environmental Assessment (BREA) - Marine Observatories. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Cryospheric Information Network (CCIN). Polardata.ca, https://doi.org/10.21335/NMDC-273201156 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Analyses presented in this paper are supported by NSF grants 1249182 (TB, IP, LP, AP), 1708427 (TB, IP, AP, SD) and 1708424 (LP). TB was supported in part by a UAF Global Change Student Research Grant award with funds from the Cooperative Institute for Alaska Research. IF received support from the Research Council of Norway through the project 294396. MJ acknowledges financial support from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF grant 03G0833).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M.B.: Data collection, data processing and writing of the data descriptor. I.V.P. and L.P.: Supervision of and contributions to data processing and the data descriptor. A.V.P., S.D., I.F., M.J. and W.W.: Contributions to data collection and to the data descriptor.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Online-only Table

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ applies to the metadata files associated with this article.

About this article

Cite this article

Baumann, T.M., Polyakov, I.V., Padman, L. et al. Arctic tidal current atlas. Sci Data 7, 275 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-00578-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-00578-z

This article is cited by

-

ArcTiCA: Arctic tidal constituents atlas

Scientific Data (2024)

-

Internal solitary wave generation by the tidal flows beneath ice keel in the Arctic Ocean

Journal of Oceanology and Limnology (2022)