Abstract

The Mexican axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) is a critically endangered species and a fruitful amphibian model for regenerative biology. Despite growing body of research on the cellular and molecular biology of axolotl limb regeneration, microbiological aspects of this process remain poorly understood. Here, we describe bacterial 16S rRNA amplicon dataset derived from axolotl limb tissue samples in the course of limb regeneration. The raw data was obtained by sequencing V3–V4 region of 16S rRNA gene and comprised 14,569,756 paired-end raw reads generated from 21 samples. Initial data analysis using DADA2 pipeline resulted in amplicon sequence variant (ASV) table containing a total of ca. 5.9 million chimera-removed, high-quality reads and a median of 296,971 reads per sample. The data constitute a useful resource for the research on the microbiological aspects of axolotl limb regeneration and will also broadly facilitate comparative studies in the developmental and conservation biology of this critically endangered species.

Design Type(s) | time series design • organism development design |

Measurement Type(s) | rRNA 16S |

Technology Type(s) | DNA sequencing |

Factor Type(s) | biological replicate • temporal_interval |

Sample Characteristic(s) | Ambystoma mexicanum • limb • laboratory environment |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data (ISA-Tab format)

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Urodele amphibians are promising vertebrate model organisms to study regeneration due to their astonishing capacity of tissue repair and renewal. Of these amphibians, Mexican axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum), a critically endangered species1, is one of the few adult animals capable of complete and functional regeneration of missing body parts throughout its life2. Axolotl can regenerate their extremities including limbs3, tail4, brain5, spinal cord6 and internal organs7 during larval and adult stages. Despite growing publicly available resources for cellular and molecular research on axolotl regeneration8,9 (e.g. transcriptome3,10,11,12,13,14, proteome15,16, and genome data17), the axolotl microbiome data remain scarcely available, which hinders comprehensive interpretation of the accumulating data in this field. As an initial effort to bridge this knowledge gap, we recently reported first multi-organ microbiome profile of axolotl at neotenic and metamorphic stages18. However, longitudinal profiling of microbial communities in the course of axolotl limb regeneration has not been reported before. Here, we describe bacterial 16S rRNA amplicon datasets derived from axolotl limb tissue samples in the course of limb regeneration.

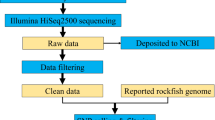

The study design aimed to profile the microbiome of limb tissues around the cut site at different stages of regeneration (0, 1, 4, 7, 30, and 60 days post-amputation, “dpa”) by sequencing 16S rRNA gene amplicons. Sampling site and time points from intact or regenerating limbs are depicted in Fig. 1a. The experimental sample collection time points corresponded to three main phases of axolotl limb regeneration, namely initiation phase (dpa 0 and dpa 1), early phase (dpa 4 and dpa 7) and late phase (dpa 30 and dpa 60). These sequential phases encompass wound healing, dedifferentiation (highlighted by blastema establishment) and re-development stages of regeneration, respectively19. The raw sequencing data comprised 14,569,756 paired-end reads generated from 21 samples. The data analysis workflow is shown in Fig. 1b. We employed DADA2 pipeline and generated an ASV abundance table containing ca. 5.9 million chimera-removed, high-quality reads and a median of 296,971 reads per sample (range: 129,428–409,656). The phyla Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria and Verrucomicrobia (Fig. 2a) dominated the bacterial communities. In addition, the obtained microbial community profile demonstrated lower intra-group variation when compared to the inter-group variation (Fig. 2a). Based on beta-diversity analyses, microbial communities of limb tissues at regeneration initiation phase, early regeneration phase, and redevelopment phase samples clearly separated (Fig. 2b,c, see methods section), indicating temporal shifts in bacterial composition between sampled tissues. Finally, aquarium water sample controls clustered separately from axolotl tissue samples (Fig. 2b,c), suggesting water microbiota colonization in axolotl limb tissues is minimal.

Experimental design. (a) The datasets generated in these experiments were derived from 21 samples in total (18 limb tissue samples and 3 aquarium water samples). Post amputation limb tissue samples were collected at these experimental timepoints: 0 dpa, 1 dpa, 4 dpa, 7 dpa, 30 dpa and 60 dpa; “dpa” denoting day post amputation. At each experimental time point groups included 3 biological replicates (R1, R2 and R3) and each replicate was formed by pooling limb tissue samples from 3 animals to minimize interindividual variation. The aquarium water samples were collected at 3 time points (day 0, day 30 and day 60) in 3 replicates (R1, R2, and R3). (b) The workflow of data analysis, the employed tools and changes in the number of processed reads at each step are shown.

Structure and diversity of bacterial communities associated with regenerating axolotl limb tissues. (a) Stacked bar chart of shows shifts in relative bacterial abundance on phylum level in the course axolotl limb regeneration. The microbial profile demonstrates temporal dynamics with the underlying differential phyla abundances in this biological process and depicts separation of aquarium control groups. (b) Hierarchical clustering of samples based on Beta-diversity analysis of ASV abundances. This chart was generated using Bray-Curtis distance metric and Ward’s method (as linkage method). (c) Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) of all studies samples based on Beta-diversity analysis of ASV abundances. This chart was generated using Bray-Curtis distance metric and PCoA ordination method. The Fig. 2b,c shows clustering of treatment samples into three main groups (corresponding to the three main stages of axolotl limb regeneration, namely wound healing, dedifferentiation and re-development) and their separation from the control group.

To date only few studies have examined the role and importance of microbiome in tissue regeneration in animals20,21. The datasets described here offer a valuable new resource for this emerging area of research and underscore the value of the axolotl as a model organism for regeneration biology. We anticipate that our data will broadly contribute to comparative and/or correlative studies employing multi-omics techniques in the developmental, regenerative, and conservation biology of amphibians.

Methods

Ethical statement

Experimental protocols and animal care conditions were approved by the local ethics committee of the Istanbul Medipol University (IMU) with authorization number 38828770-433.

Animal husbandry and experimental design

In this study, 54 adults (1-year-old, 12–15 cm in length) axolotls chosen randomly among siblings were included. Founders of initial axolotl colony was purchased from Kentucky, USA and maintained and bred in animal care facility of the IMU in keeping with the established protocols22. The randomly picked experimental animals were then housed separately as one individual in a cuboid shaped aquarium filled with Holtfreter’s solution at 18 ± 2 °C temperature and maintained at this temperature throughout the experiments. The animals were fed once a day with a staple food (JBL Novo LotlM, Neuhofen, Germany). The experimental design is depicted in Fig. 1a. In each group, 9 animals were randomly sub-grouped into three biological replicates (R1, R2 and R3) to assess the replicability of the results. During the experimental period all animals were maintained as one animal per aquaria. To amputate axolotl limbs, we first anesthetized the animals using 0.1% Tricaine methane sulfonate (Cat. No. E10521 or MS-222, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) then amputated the right forelimb of each animal at mid-zeugopod level. Following the amputation, we randomly selected the amputated animals to form six groups representing three main phases of axolotl limb regeneration, the initiation phase (dpa 0 and dpa 1), the early phase (dpa 4 and dpa 7) and the late phase (dpa 30 and dpa 60). To minimize the variation between individuals, tissue samples from three animals were pooled together for each biological replicate. All tissue samples were cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen immediately after the collection and stored at −80 °C until genomic DNA isolation. Dpa 0 and dpa 1 samples were isolated from approximately 1-mm tissue around the cut site. Dpa 4 and dpa 7 were isolated by removing the newly formed blastema and 0.5 mm posterior tissue from the cut site since 0.5 mm posterior tissue of cut site was previously reported to be important zone for dedifferentiation of cells into stem/progenitor cells23. To sample the microbiota of the restored tissues in the newly formed limbs, dpa 30 and dpa 60 samples were again collected around the original cut site.

To investigate whether microbiota in Holtfreter’s solution colonized axolotl limbs, we collected water samples (100 ml) from a total of 9 individual aquaria in the course of experimental timeline. We pooled water samples from aquaria of 3 axolotls at the beginning (day0-R1), 3 water samples in the middle (day30-R2), and 3 at the end (day60-R3) and named these samples the “aqua” control group, resulting 3 replicates (R1, R2, R3; see Fig. 1a).

DNA extraction, PCR and 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing

DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Cat No. 69504) was used to isolate genomic DNA from the collected samples by following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA of water samples was extracted by using ‘Metagenomic DNA Isolation Kit for Water’ (Epicentre, Cat. No. MGD08420). Concentrations of the isolated genomic DNA samples were determined using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and dsDNA BR Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Cat. No. Q32850). Integrity of the DNA samples were ascertained by running an aliquot of the DNA samples on a 1.0% agarose gel. Primers 337F (5′-GACTCCTACGGGAGGCWGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′), with tails of Nextera adapter sequences were used to amplify the targeted V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene, as described in the illumina 16S rRNA metagenomic sequencing protocol.

For each sample, PCR was carried out in total volume of 25 µl reaction mixture which included 12.5 ng of purified DNA template and 2x KAPA HiFi HotStart Ready Mix. The following order of steps and conditions was used for PCR: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 minutes and 25 cycles of; denaturation at 95 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 55 °C for 30 seconds and extension at 72 °C for 30 seconds, with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 minutes. The PCR products were purified by using Agencourt AMPure XP purification system (Beckman Coulter, Cat. No. A63881, USA) and second PCR (with 8 cycles) was performed by using sample-specific barcodes and the obtained amplicons were purified again. Equimolar concentrations from each library were then pooled and sequenced on Illumina MiSeq sequencer using MiSeq Reagent Kit v2, 500 cycles. The obtained sequences were on average 231 bp long. The raw data resulting from this sequencing effort can be found in NCBI Sequence Read Archive24. Accession numbers, sample source and experimental time point from each sample can be found in Table 1.

Data analysis

The overview of the data analysis workflow is shown in Fig. 1b. Demultiplexing and clipping of sequence adapters and barcodes from raw sequences were performed using the Illumina BaseSpace platform (Illumina). The resulting 16S rRNA paired-end raw sequencing data comprised in total ca. 14.6 million reads generated from 21 samples. We then employed cutadapt program25 v1.13 (default parameters) to remove the primers preceding 16S rRNA amplicon reads. The primer-removed raw sequences were subsequently uploaded to the online Nephele analysis platform v2 together with the mapping file26, which describes the individual raw data files to otherwise entirely automatic online pipeline. The FastQC software27, which is part of the Nephele Pre-processing Quality Check (QC) pipeline, was used to check the quality of the Illumina sequencing reads before the reads were fed into the Nephele DADA2 pipeline (which implements DADA2 package, v1.628). The logfiles generated by the two pipelines26 describe each step in data processing.

The DADA2 software integrated to Nephele DADA2 pipeline automatically performed quality check prior to data analysis. Briefly, after quality check (Supplementary Figs 1 and 2), the pipeline performs quality trimming and filtering, dereplicates sequences, learns error rates (Supplementary Figs 3 and 4), removes sequences potentially containing errors (denoising), merges paired-end reads as contigs, screens contigs for mismatches to reduce errors, constructs amplicon sequence variant (ASV) abundance table, removes chimeric sequences (using “bimera” method), runs taxonomic classification of ASVs using SILVA reference (SILVA 132 release) database29. In the quality trimming and filtering step, “truncation quality score equal to 4 (truncQ = 4)” parameter was selected and reads with maximum expected errors greater than 5 were discarded as a quality filtering measure (using “maxEE = 5” parameter). The pipeline detected 7.4% of all reads (in terms of relative abundance) as chimeric (“bimera”) and removed from datasets. The resulting ASV table26 thereby retained high quality nonchimeric reads (5.9 million reads in total generated from 21 samples, with the median 296,842 reads per sample).

Sequencing depth of raw data and number of reads per sample remaining after each data analysis step are shown in Table 2. Rarefaction plot for the ASV abundance dataset ensured sufficient depth for sample comparison (Supplementary Fig. 5). Downstream analysis included data inspection, normalization, abundance visualization and beta-diversity analysis steps. This part of the workflow was performed using the freely available web-based tool, “MicrobiomeAnalyst”30, specifically the Marker Data Profiling (MDP) module integrated into this webtool. After initial data filtering step 786 ASVs were used for the subsequent analyses. The normalization step was performed to account for compositional differences by applying rarefaction to the minimum library size and data scaling based on the Total Sum Scaling (TSS) method. The normalized ASV abundance data was used for visualization of ASV relative abundances and beta-diversity analysis. Relative phylum-level abundances were shown in stacked barplot (Fig. 2a). Beta-diversity of bacterial communities in the limb samples were shown using hierarchical clustering (Ward’s linkage method) (Fig. 2b) and the Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis index31 (Fig. 2c) and tested using Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) (F-value: 8.4063; R-squared: 0.78274; p-value < 0.001), Homogeneity of Group Dispersions (PERMDISP)32 (F-value: 1.5975; p-value: 0.21993), and Analysis of Group Similarities (ANOSIM) (R: 0.90577; p-value < 0.001).

Data Records

The 16S rRNA gene sequencing raw data (paired-end reads) were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive24 under the BioProject ID PRJNA482947 with the SRA accession number SRP155412. The deposited dataset consists of 42 compressed FASTQ paired-end files (forward and reverse reads), generated from 21 samples. The supplementary files can be found within the Figshare repository26.

Technical Validation

Our unique experimental design (Fig. 1a) enabled us to assess both biological and technical variations. Of the limb tissues we collected we pooled 9 biological tissue samples into 3 biological replicates to reduce and assess within and between group variations. We also ensured to include negative controls in genomic DNA extractions and no template controls in all PCR runs; no detectable bands were observed on agarose gel electrophoresis from these controls. Furthermore, aquarium water samples were used as control group to assess the profile of microbiota in axolotl’s aqueous environment.

Quality profiles generated by the quality control step based on Phred quality scores (Supplementary Figs 1 and 2) and the learning error rates step of the Nephele DADA2 pipeline (Supplementary Figs 3 and 4) assisted in optimizing the quality trimming and filtering. The recently developed ASV-based approach was preferred over the traditional OTU-based approaches for assessing microbiome abundance since this novel approach has been shown to generate more precise and accurate results for analysis of 16S rRNA data28,33,34. As an ASV-based method, the novelty and resulting improved resolution of the DADA2 package performance comes especially from the dereplication and denoising functionalities28.

Finally, to further demonstrate usability and replicability of the datasets described here, we included 16S rRNA sequencing data from limb skin samples, which we collected in our previous study18. The obtained results indicated that skin samples from our previous study were very similar to the regeneration initiation phase samples (Supplementary Figs 6 and 7).

Code Availability

No custom codes were used in generating or processing of the dataset described herein.

References

Zambrano, L. et al. Ambystoma mexicanum. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2010: e.T1095A3229615. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-2.RLTS.T1095A3229615.en (2010).

Carlson, B. M. Principles of regenerative biology. (Elsevier, 2011).

Bryant, D. M. et al. A tissue-mapped axolotl de novo transcriptome enables identification of limb regeneration factors. Cell Reports 18, 762–776 (2017).

Vincent, C. D., Rost, F., Masselink, W., Brusch, L. & Tanaka, E. M. Cellular dynamics underlying regeneration of appropriate segment number during axolotl tail regeneration. BMC Developmental Biology 15, 48 (2015).

Richter, W. Regenerative processes following removal of the caudal sector of the telencephalon including the telencephalo-diencephalic border region in Ambystoma mexicanum. Journal fur Hirnforschung 10, 515 (1968).

Mchedlishvili, L., Epperlein, H. H., Telzerow, A. & Tanaka, E. M. A clonal analysis of neural progenitors during axolotl spinal cord regeneration reveals evidence for both spatially restricted and multipotent progenitors. Development 134, 2083–2093 (2007).

Nakamura, R. et al. Expression analysis of Baf60c during heart regeneration in axolotls and neonatal mice. Development, Growth & Differentiation 58, 367–382 (2016).

Haas, B. J. & Whited, J. L. Advances in decoding axolotl limb regeneration. Trends in Genetics 33, 553–565 (2017).

Poss, K. D. Advances in understanding tissue regenerative capacity and mechanisms in animals. Nature Reviews Genetics 11, 710 (2010).

Gerber, T. et al. Single-cell analysis uncovers convergence of cell identities during axolotl limb regeneration. Science 362, eaaq0681 (2018).

Jiang, P. et al. Analysis of embryonic development in the unsequenced axolotl: Waves of transcriptomic upheaval and stability. Developmental Biology 426, 143–154 (2017).

Knapp, D. et al. Comparative transcriptional profiling of the axolotl limb identifies a tripartite regeneration-specific gene program. PLoS One 8, e61352 (2013).

Stewart, R. et al. Comparative RNA-seq analysis in the unsequenced axolotl: the oncogene burst highlights early gene expression in the blastema. PLoS Computational Biology 9, e1002936 (2013).

Voss, S. R. et al. Gene expression during the first 28 days of axolotl limb regeneration I: Experimental design and global analysis of gene expression. Regeneration 2, 120–136 (2015).

Demircan, T. et al. Detailed tail proteomic analysis of axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) using an mRNA‐seq reference database. Proteomics 17, 1600338 (2017).

Rao, N. et al. Proteomic analysis of blastema formation in regenerating axolotl limbs. BMC Biology 7, 83 (2009).

Nowoshilow, S. et al. The axolotl genome and the evolution of key tissue formation regulators. Nature 554, 50 (2018).

Demircan, T. et al. Experimentally induced metamorphosis in highly regenerative axolotl (ambystoma mexicanum) under constant diet restructures microbiota. Scientific Reports 8, 10974 (2018).

Bryant, S. V., Endo, T. & Gardiner, D. M. Vertebrate limb regeneration and the origin of limb stem cells. International Journal of Developmental Biology 46, 887–896 (2004).

Arnold, C. P. et al. Pathogenic shifts in endogenous microbiota impede tissue regeneration via distinct activation of TAK1/MKK/p38. eLife 5, e16793 (2016).

Liu, H.-X., Rocha, C. S., Dandekar, S. & Wan, Y.-J. Y. Functional analysis of the relationship between intestinal microbiota and the expression of hepatic genes and pathways during the course of liver regeneration. Journal of Hepatology 64, 641–650 (2016).

Khattak, S. et al. Optimized axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) husbandry, breeding, metamorphosis, transgenesis and tamoxifen-mediated recombination. Nature Protocols 9, 529 (2014).

Currie, J. D. et al. Live imaging of axolotl digit regeneration reveals spatiotemporal choreography of diverse connective tissue progenitor pools. Developmental Cell 39, 411–423 (2016).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive, http://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP155412 (2018).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. Journal 17, 10–12 (2011).

Demircan, T., İlhan, A. E., Ovezmyradov, G., Öztürk, G. & Yıldırım, S. Monitoring microbiome dynamics of axolotl limb regeneration. figshare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.4443044 (2019).

Andrews, S. A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. FastQC, http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (2014).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nature Methods 13, 581 (2016).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res 41, D590–596 (2013).

Dhariwal, A. et al. MicrobiomeAnalyst: a web-based tool for comprehensive statistical, visual and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nucleic Acids Research 45, W180–W188 (2017).

Bray, J. R. & Curtis, J. T. An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecological Monographs 27, 325–349 (1957).

Anderson, M. J. Distance‐based tests for homogeneity of multivariate dispersions. Biometrics 62, 245–253 (2006).

Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. P. Exact sequence variants should replace operational taxonomic units in marker-gene data analysis. The ISME Journal 11, 2639 (2017).

Knight, R. et al. Best practices for analysing microbiomes. Nature Reviews Microbiology 16, 410–422 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study used the Nephele platform (https://nephele.niaid.nih.gov/) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Office of Cyber Infrastructure and Computational Biology (OCICB) in Bethesda, MD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.D. and S.Y. conceived the study and experiments. T.D. and A.E.İ. performed animal experiments, extraction of the DNA and sample preparation for sequencing. T.D., G.O., G.Ö. and S.Y. analyzed and interpreted the data. T.D., G.O. and S.Y. drafted and critically reviewed/revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

ISA-Tab metadata file

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ applies to the metadata files associated with this article.

About this article

Cite this article

Demircan, T., İlhan, A.E., Ovezmyradov, G. et al. Longitudinal 16S rRNA data derived from limb regenerative tissue samples of axolotl Ambystoma mexicanum. Sci Data 6, 70 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0077-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0077-7

This article is cited by

-

Characterization of bacterial diversity in wastewater of Indian paper industries with special reference to water quality

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology (2022)